Significance

DEC205 (CD205) is an endocytotic receptor on dendritic cells that recognizes dead cells in a pH-dependent fashion and has been widely used for vaccine generation in immune therapies. However, the physiological ligand(s) of DEC205 has remained unknown for decades. Here we identify that keratins are the cellular ligands of human DEC205 and DEC205 recognizes keratins specifically at acidic pH. Keratins are structural proteins providing mechanical support for cells and tissues. Our results suggest that keratins act as markers of dead cells in acidic environments. Moreover, since keratins have been used as diagnostic markers for various tumors, the finding of DEC205 as a scavenging receptor of keratins may provide insights for the therapeutic strategies against tumors and other related diseases.

Keywords: DEC205/CD205, keratin, dead cell recognition, mannose receptor family, cell death

Abstract

Clearance of dead cells is critical for maintaining homeostasis and prevents autoimmunity and inflammation. When cells undergo apoptosis and necrosis, specific markers are exposed and recognized by the receptors on phagocytes. DEC205 (CD205) is an endocytotic receptor on dendritic cells with antigen presentation function and has been widely used in immune therapies for vaccine generation. It has been shown that human DEC205 recognizes apoptotic and necrotic cells in a pH-dependent fashion. However, the natural ligand(s) of DEC205 remains unknown. Here we find that keratins are the cellular ligands of human DEC205. DEC205 binds to keratins specifically at acidic, but not basic, pH through its N-terminal domains. Keratins form intermediate filaments and are important for maintaining the strength of cells and tissues. Our results suggest that keratins also function as cell markers of apoptotic and necrotic cells and mediate a pH-dependent pathway for the immune recognition of dead cells.

The immune system is responsible for removing self-antigens such as dead cells to maintain tissue homeostasis and prevent autoimmunity (1–3). Dead cells are recognized and engulfed by phagocytes through their cell surface receptors (4), leading to either immune activation or tolerance (5–8). A number of receptors have been found to be able to mediate the clearance of dead cells (3); for example, CD14 (9), CD36 (10), integrin (11), PtdSerR (12), CLEC9A (13–15), and TIM receptor family members (16). Among known dead cell markers, phosphatidylserine (PS) is the most common one that can be recognized by several receptors such as CD36, PtdSerR, and TIM receptors, and acts as an “eat-me” signal for phagocytes mediating dead cell clearance (4). Other than PS, several cellular proteins have also been found to be able to perform the similar function. For example, actin filaments can be recognized by CLEC9A as a damaged cell marker (13, 15). The recognition of different dead cell markers by phagocytes provides an efficient way to remove cell debris completely.

Keratins are important cytoskeletal components and form intermediate filaments in cytoplasm. There are 54 known members in the keratin family that are divided into two types based on their isoelectric points and sequences (17). Keratin monomers can assemble into bundles first and then form fibrous filaments ∼10 nm in diameter, which act as a scaffold and provide mechanical support for maintaining the strength and toughness of cells and tissues (18, 19). Recently, evidence has accumulated showing that keratins play physiological roles in addition to their structural functions, for example, in cell growth, proliferation, mobility, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis (18, 20, 21).

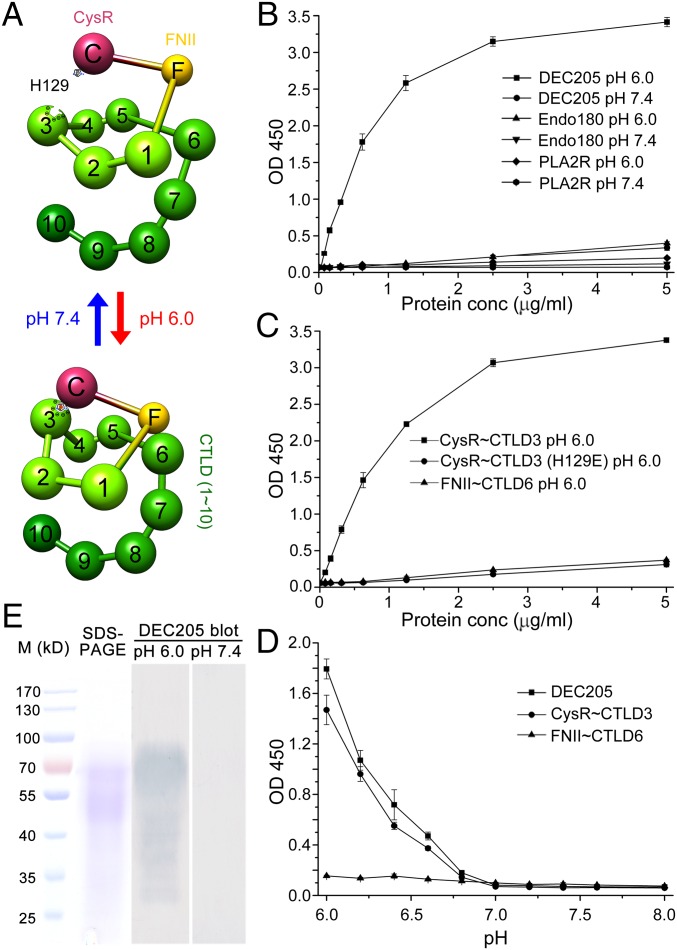

DEC205 (CD205 or Ly75, molecular mass of 205 kDa) is an endocytotic receptor highly expressed on dendritic cells and thymic epithelial cells (8, 22) and capable of inducing either tolerance or immunity in the absence or presence of inflammatory stimuli (23). DEC205 belongs to the mannose receptor family (24), which includes five members: the mannose receptor, DEC205, Endo180, PLA2R, and FcRY (25). Structural results indicate that these receptors share similar structural features (26–28). Their ectodomains begin with a cysteine-rich domain (CysR), followed by a fibronectin type II domain (FNII) and 8 (10 for DEC205) C-type lectin-like domains (CTLDs). Recently, our data indicate that the ectodomain of DEC205 adopts a double-ringed conformation at acidic pH and also show that DEC205 recognizes apoptotic and necrotic cells specifically in acidic environments through its N-terminal smaller ring (27), suggesting that it mediates a different dead cell recognition pathway from the previously identified receptors. However, because the physiological ligand(s) of DEC205 has not been found, the mechanism of this pathway remains unknown.

Here we identified the natural ligand(s) of DEC205 by a series of biochemical and biophysical assays and found that keratins were the cellular ligands of DEC205. DEC205 binds to keratins at acidic pH through its N-terminal smaller ring, suggesting that DEC205 is a pH-dependent keratin receptor mediating the immune recognition of apoptotic and necrotic cells.

Results

DEC205 Recognizes Protein Ligands on Apoptotic and Necrotic Cells.

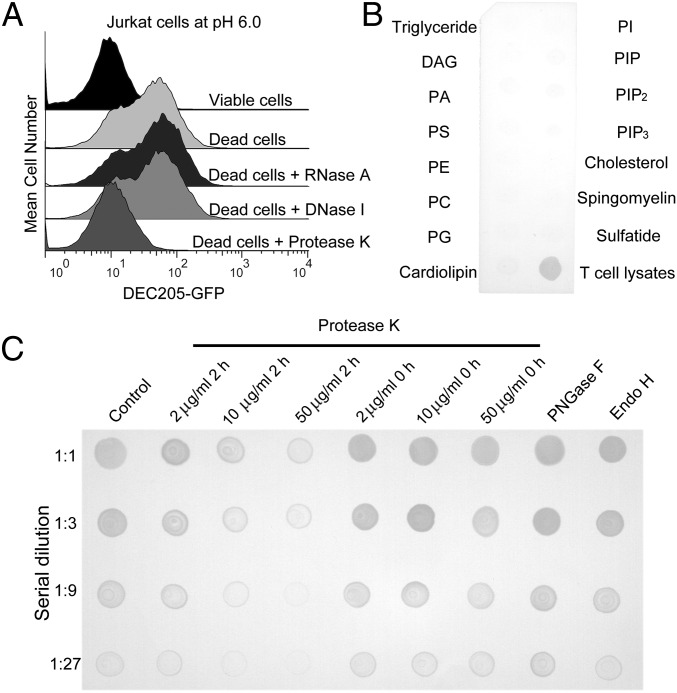

To identify the ligand of DEC205, we treated dead (apoptotic and necrotic) cells with a number of enzymes including protease K, DNase I, and RNase A (Fig. 1A). The results showed that only the protease K treatment abolished DEC205 binding to dead cells. In parallel, we also tested the lipid binding activities of DEC205 by dot-blot assays, and no obvious binding was detected (Fig. 1B). To verify this result, we treated HEK293 cell lysates with protease K at different concentrations and with different incubation time in the dot-blot assays (Fig. 1C). Similarly, the glycosidases PNGase F and Endo H were applied to cell lysates to evaluate the carbohydrate binding activity of DEC205 (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). The results showed that the binding of DEC205 to dead cells diminished gradually as the protease K concentration and incubation time increased, whereas glycosidase treatments had no effect to the binding. Taken together these results suggest that the DEC205–ligand interaction is protein dependent, rather than lipid or glycan dependent.

Fig. 1.

Human DEC205 recognizes protein ligands on apoptotic and necrotic cells. (A) The binding of DEC205 to dead cells was abolished by protease K treatment. (B) DEC205 showed no binding activity to the lipids on the lipid strip. T-cell lysates were spotted as a positive control. (C) The binding of DEC205-Fc to HEK293 lysates was diminished by protease K treatment in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. PNGase F and Endo H treatments had no effect on the binding of DEC205-Fc to HEK293 lysates.

Fig. S1.

Lipid strip and glycosidase treatment assays. (A) The PIP2 lipid was detected by the PIP2 binding protein P(4, 5)P2 grip on the lipid strip. The assay was performed as a control for the DEC205 lipid strip experiments shown in Fig. 1B. (B) The SDS/PAGE of the smaller ring of human DEC205 treated with Endo H or PNGase F, showing the deglycosylation efficacy of the enzymes.

Keratins Are the Cellular Ligands of DEC205.

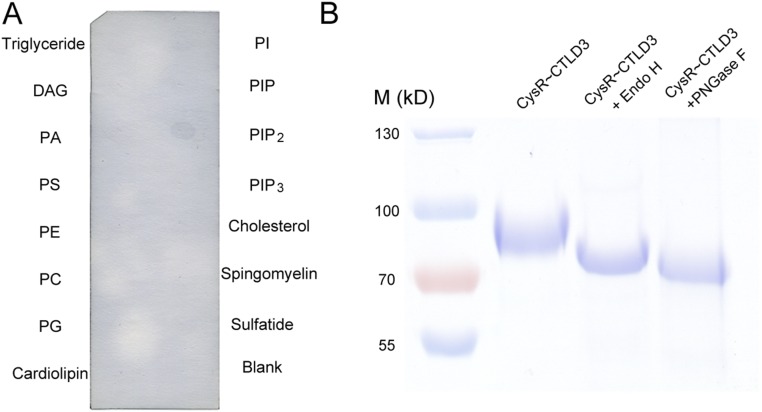

To isolate the protein ligands of DEC205, biotinylated DEC205 was incubated with apoptotic HEK293 cells at pH 6.0 and cross-linked by 2% paraformaldehyde. The cells were then washed with PBS at pH 7.4 to remove uncross-linked DEC205. Then cells were lysed and loaded onto streptavidin beads to remove the unbound material. The boiled beads were analyzed by SDS/PAGE showing a high molecular weight band, whereas the control sample without paraformaldehyde cross-linking showed no obvious band (Fig. 2A). Mass spectrometry analysis of the band indicated that it contained mostly keratins along with DEC205 (Fig. 2B). This result implied that keratins could be the cellular ligands of DEC205. To verify the cross-linking results, we used a different method for ligand isolation. A human DEC205 ectodomain fused with an IgG Fc fragment (DEC205-Fc) was mixed with Jurkat cell lysates at pH 6.0, purified with protein A/G beads, and then eluted at pH 8.0. An IgG Fc fragment alone was used as a control. Mass spectrometry results showed that DEC205-Fc pulled down more keratins than Fc alone and keratins were the major proteins showing large differences over the control (Fig. 2 C and D), suggesting keratins were the ligands of DEC205 under acidic conditions. The different mass spectrometry counts of identified keratins may correlate with their molecular weights and the binding affinities with DEC205 or the cell lines used in the experiments. In addition, because keratin members are assembled into filaments with each other, some of them may be pulled out without having direct interactions with DEC205. By contrast, the mass spectrometry counts of the proteins previously identified as dead cell markers, such as calreticulin or actin, are only at background level, suggesting they might not have interactions with DEC205.

Fig. 2.

Keratins are the cellular ligands of human DEC205. (A) SDS/PAGE of the ligand isolation by cross-linking. Apoptotic HEK293 cells were incubated with biotinylated DEC205, washed, and cross-linked with paraformaldehyde or mock cross-linked with PBS. The lysates were purified by streptavidin beads and loaded onto SDS/PAGE showing a high molecular weight band (red square). The top hits of mass spectrometry results obtained from the band are shown in B. (C and D) Mass spectrometry results of direct pull-down experiments showed a larger amount of keratins were pulled down by DEC205-Fc than Fc alone. The count of each protein represents the summation of the number of times of its peptides detected by mass spectrometry.

DEC205 Binds Keratins at Acidic pH Through Its N-Terminal Smaller Ring.

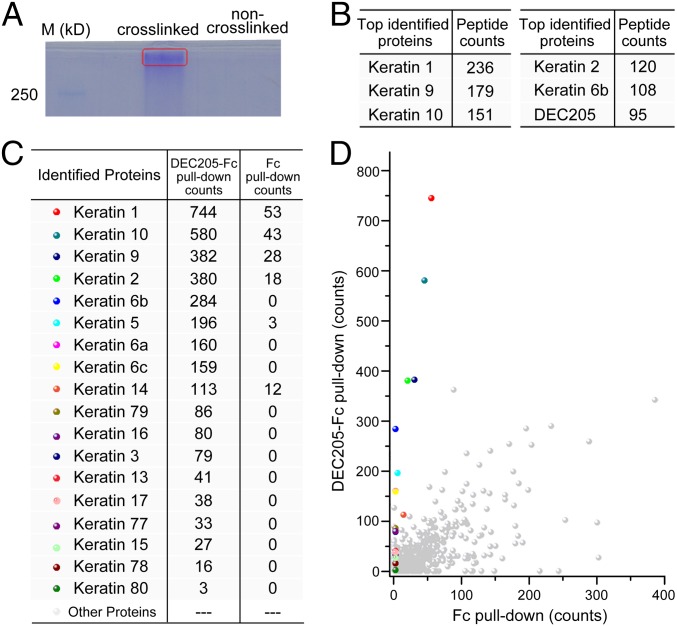

To verify the interactions between DEC205 and keratins, we evaluated the binding of DEC205 to keratins in vitro using a series of ELISA experiments. Human keratins derived from epidermis were immobilized on ELISA plates, and DEC205-Fc protein was added at different concentrations and at different pH values. The data showed that the binding of DEC205 to keratins was pH dependent (Fig. 3 B and D). DEC205 only bound to keratins at acidic pH and lost detectable binding at around pH 6.8 (Fig. 3D). A similar binding profile was observed for an N-terminal fragment of DEC205, CysR∼CTLD3 (Fig. 3 C and D), which adopts a ring-shaped conformation (the smaller ring) at acidic pH (Fig. 3A) (27). In contrast, the DEC205 fragment FNII∼CTLD6, which forms a larger ring at acidic pH (Fig. 3A), exhibited no binding affinity to keratins at either acidic or basic conditions (Fig. 3 C and D), suggesting DEC205 recognizes keratins through its N-terminal smaller ring. In our previous studies, we identified a single mutant (H129E) on the smaller ring that abolished the DEC205 binding to apoptotic and necrotic cells (Fig. 3A) (27). Similarly, ELISA results showed that this mutant had no binding affinity to keratins either (Fig. 3C), thus supporting the specific interactions between DEC205 and keratins. In addition, we tested the binding of keratins with Endo180 and PLA2R, which are also the members of the mannose receptor family. The data showed that neither Endo180 nor PLA2R had keratin binding activities (Fig. 3B). Besides ELISA experiments, we also evaluated DEC205 interactions with keratins using Western blot assays (Fig. 3E). Human keratins were loaded onto SDS/PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and blotted by DEC205-Fc at either pH 6.0 or pH 7.4. Indeed, the bands of keratins were only detected at acidic pH rather than at basic pH (Fig. 3E). Because proteins were usually linearized on SDS/PAGE, this result implied that DEC205 may recognize linear sequence motifs on keratins, as had been observed in the cases of bacterial proteins ClfB (29) and Srr-1 (30).

Fig. 3.

Human DEC205 binds to keratins at acidic pH with its N-terminal smaller ring. (A) Ball-and-stick models of DEC205 showing its domain arrangement and the pH-dependent conformational change. (B) DEC205 bound to human keratins at pH 6.0 rather than at pH 7.4. The ectodomains of Endo180 and PLA2R showed no binding activities to keratins at either pH 6.0 or pH 7.4. (C) The N-terminal smaller ring (CysR∼CTLD3) of DEC205 bound to keratins at pH 6.0, whereas the larger ring (FNII∼CTLD6) and the smaller ring mutant (H129E) showed no keratin binding affinities. (D) DEC205 and its N-terminal smaller ring bound to keratins in a pH-dependent manner. (E) Western blot assays showed that DEC205 bound to human keratins at acidic, rather than basic, pH. The SDS/PAGE of human keratins is shown on the Left.

DEC205 Recognizes the C-Terminal Gly-Rich Region of Keratins.

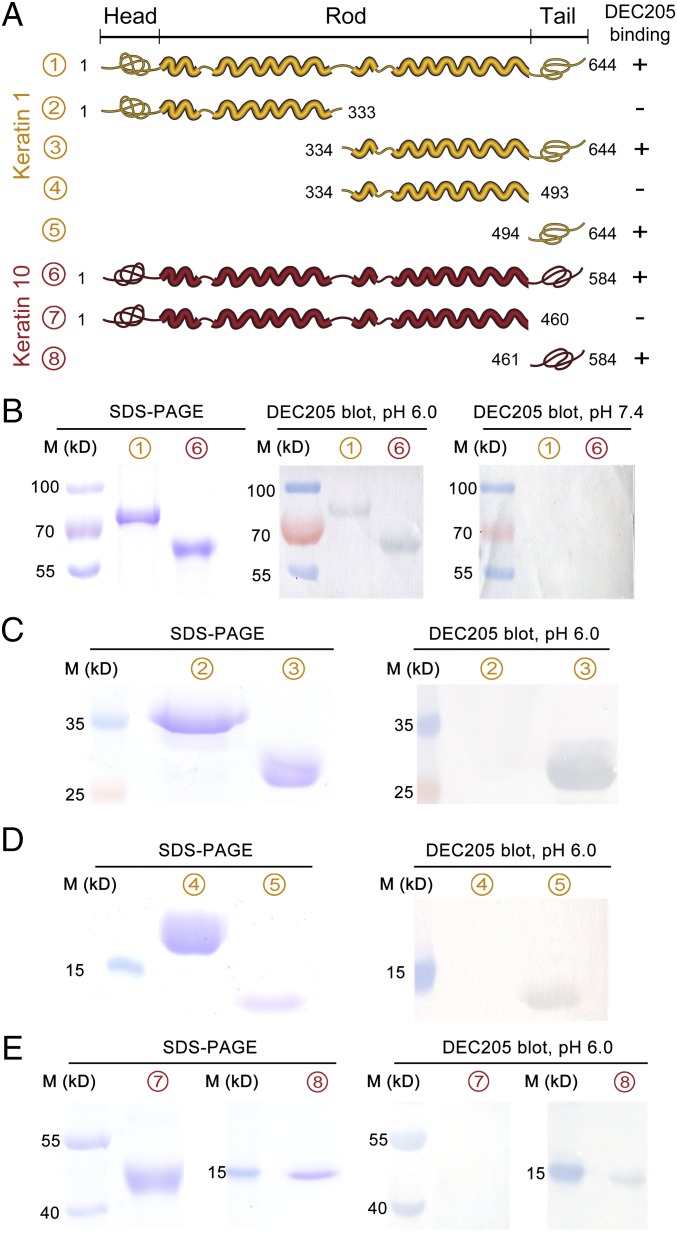

To further characterize the interactions of DEC205 with keratins, full-length human keratin 1 and keratin 10 were both expressed in Escherichia coli and purified from inclusion bodies. The interactions of DEC205 with purified keratins were investigated by Western blot assays as discussed above. The results showed that DEC205 bound to keratin 1 and keratin 10 only at acidic pH (Fig. 4B), confirming the direct interactions between DEC205 and keratins. The structures of keratins usually contain a central α-helical rod domain that is flanked by a nonhelical head and a tail domain (31) (Fig. 4A). To narrow down the binding region of DEC205 on keratins, we expressed a series of truncation fragments of keratin 1 for Western blot assays (Fig. 4A). The results showed that DEC205 only recognized the C-terminal tail domain of keratin 1 specifically at acidic pH (Fig. 4 C and D), which contains a high percentage of glycine and serine in sequence, a feature shared by many keratin family members (32). Similarly, two truncation mutants of keratin 10 were also expressed for binding assays (Fig. 4A), and results showed that only the tail domain of keratin 10 could be recognized by DEC205 at acidic pH (Fig. 4E). The interactions of DEC205 with keratin tails were also evaluated by ELISA (Fig. 5C), which validated the pH-dependent binding properties of DEC205 with keratins.

Fig. 4.

Human DEC205 binds to the C-terminal tail domains of keratin 1 and keratin 10 at acidic pH. (A) Schematic representation of keratin 1 (yellow) and keratin 10 (red) domain arrangement and their truncation mutants expressed for binding assays. (B) DEC205 bound to the full-length keratin 1 and 10 at acidic pH. (C and D) Western blot assays showed that DEC205 bound to the C-terminal tail domain of keratin 1 at acidic pH. (E) Western blot assays showed that DEC205 bound to the C-terminal tail domain of keratin 10 at acidic pH.

Fig. 5.

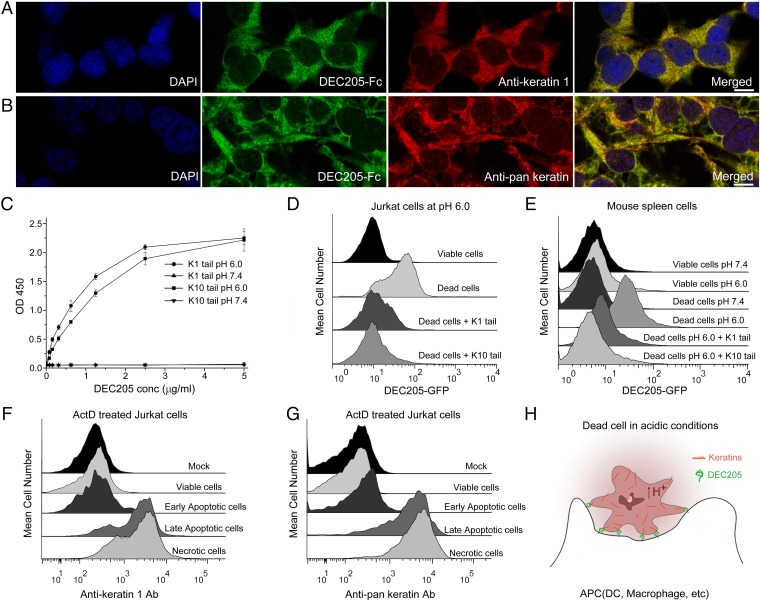

Human DEC205 binds to cellular keratins at acidic pH. (A) DEC205 colocalized with anti-keratin 1 antibody in HEK293 cells at pH 6.0. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) DEC205 colocalized with anti-pan keratin antibody in HEK293 cells at pH 6.0. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) ELISA experiments showed that DEC205 bound to the C-terminal tail domains of keratin 1 and keratin 10 at acidic pH. (D) The tail domains of keratin 1 and keratin 10 blocked the binding of DEC205 to dead cells. (E) DEC205 bound to the frozen-thawed mouse spleen cells at acidic pH and the binding was blocked by the tail domains of keratin 1 and keratin 10. (F and G) ActD-treated Jurkat cells were stained with Annexin V and PI to differentiate the stages of viable cells (Annexin V−PI−), early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+PI−), late apoptotic/early necrotic cells (Annexin V+PI+), and necrotic cells (Annexin V+PI++). The exposure of keratins on the surface of cells was monitored by anti-keratin 1 antibodies (F) and anti-pan keratin antibodies (G). Anti-keratin antibodies were not added under mock conditions. (H) A cartoon representation of the recognition of apoptotic and necrotic cells by human DEC205 through keratins in acidic conditions.

DEC205 Recognizes Cellular Keratins at Acidic pH.

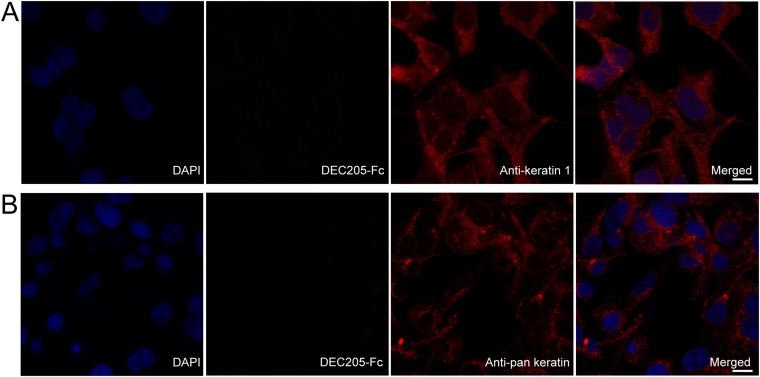

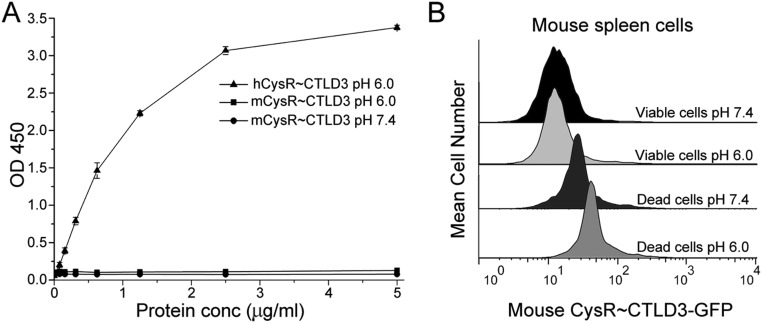

To investigate the interactions of DEC205 with cellular keratins, we stained permeabilized HEK293 cells with both anti-keratin 1 antibody and DEC205-Fc. Fluorescent images showed that keratin 1 and DEC205 were well colocalized at acidic pH (Fig. 5A and Fig. S2A), suggesting the specific interactions between the two proteins. In parallel, an anti-pan keratin antibody was also used for colocalization assay with DEC205-Fc, and similar results were observed (Fig. 5B and Fig. S2B), thus confirming the in vitro binding results of DEC205 and keratins. Our previous results indicated that DEC205 could bind to the apoptotic and necrotic cells specifically at acidic pH (27). Therefore, if keratins are the cellular ligands of DEC205, the keratin tail fragments identified above should be able to inhibit the binding of DEC205 to dead cells. Indeed, the FACS results showed that the tail fragments of keratin 1 and keratin 10 could block the binding of DEC205 to dead cells almost completely (Fig. 5D), suggesting that keratins are the specific ligands of DEC205 on these cells. Furthermore, we repeated binding/inhibition experiments using primary cells isolated from mouse spleen and obtained similar results (Fig. 5E). These results are expected because the C-terminal Gly-rich motif is shared among many mouse keratin members. We also expressed the N-terminal smaller ring of mouse DEC205 (CysR∼CTLD3), and found that it could recognize mouse dead cells and exhibited higher binding affinity under acidic pH (Fig. S3B). Interestingly, although human DEC205 could bind to mouse dead cells probably through keratins (Fig. 5E), the smaller ring of mouse DEC205 did not show binding affinities to human keratins (Fig. S3A). These results suggest that mouse DEC205 might also be a receptor for dead cells (33), but its interactions with the ligand may be different from human DEC205. To evaluate the recognition of DEC205 with keratins on cell surface, we stained the ActD-treated Jurkat cells with annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) to differentiate the stages of apoptosis and necrosis and compared the exposure of keratins on the surface of dying cells using anti-keratin 1 and anti-pan keratin antibodies (Fig. 5 F and G). The FACS data showed that keratins were marginally exposed at the early stage of apoptosis and largely exposed at and after the late stage of apoptosis, suggesting that DEC205 recognizes dying cells mainly at the stages of late apoptosis and necrosis.

Fig. S2.

Human DEC205 shows no binding to cellular keratins at basic pH. (A) Permeabilized HEK293 cells stained with DEC205-Fc and anti-keratin 1 antibody at pH 7.4. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) Permeabilized HEK293 cells stained with DEC205-Fc and anti-pan keratin antibody at pH 7.4. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Fig. S3.

Ligand binding properties of the smaller ring of mouse DEC205 (CysR∼CTLD3). (A) The smaller ring of mouse DEC205 had no binding activities to human keratins at either pH 6.0 or pH 7.4. The smaller ring of human DEC205 bound to human keratins at pH 6.0. (B) The smaller ring of mouse DEC205 bound to the frozen-thawed mouse spleen cells and showed higher binding affinity at acidic pH.

Discussion

As a member of the mannose receptor family, DEC205 has been suggested to be able to bind various targets (33, 34); however, the natural ligands of DEC205 remained a mystery for decades (22). Recently we have shown that DEC205 could recognize apoptotic and necrotic cells specifically in a pH-dependent fashion (27), thus providing the feasibility to identify its cellular ligands. Previous data also imply that the binding of DEC205 to apoptotic cells does not require protein synthesis (27, 33), suggesting the ligands could be existing protein components, consistent with the finding of keratins as the ligands of DEC205. It has been shown that keratins may undergo a variety of posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation and glycosylation (35); our results suggest that these modifications may not affect the recognition between keratins and DEC205. Recent evidence shows that the mannose receptor family members might share similar structural features (26–28, 36), but their natural ligands are different. The finding of keratins as the ligands of DEC205 adds more diversity to the receptor–ligand interactions of this family.

A keratin monomer usually contains three domains: an N-terminal head, a middle rod-forming domain, and a C-terminal tail. The DEC205 binding data show that it only recognizes the C-terminal tail domains of keratin 1 and keratin 10, and notably, the binding tests can be done by Western blot assays, suggesting that the target sequence of DEC205 on keratins adopts a linear conformation. Indeed, the tail domains of keratin 1 and keratin 10 contain a high percentage of glycine and serine in a X(Y)n format, where X represents an aromatic or a long-chain aliphatic residue and Y is either glycine or serine (32, 37). The X(Y)n pattern is quasirepetitive and may form “glycine loops” where the Gly-rich peptides have flexible loop-like structures without rigid conformations (37), thus explaining the results of Western blot assays. Recently, it has been shown that a bacterial protein ClfB could recognize the Gly-rich tail domain of keratin 8 and keratin 10 (38, 39), and the crystal structure of ClfB complexed with the keratin 10 tail shows that the Gly-rich sequence also adopts a linear conformation (29). In fact, the Gly-rich sequences are found in the C-terminal tail domains of many keratin members including both type I and type II keratins (32, 37), suggesting that DEC205 might be a generic receptor for keratins targeting to these sequences.

Because keratins form an intermediate filament network and distribute all over the cytoplasm, they could be an efficient marker for dead cells or cell debris. Our results show that keratins are gradually exposed as apoptosis proceeds and become accessible to DEC205. Evidence has also shown that during apoptosis, keratins can be degraded and redistributed and serve as a regulating factor (40, 41), which may increase their association with cell debris and also the accessibility to receptors. This is consistent with the previous observation showing that the binding affinity of DEC205 to dead cells increases as apoptosis proceeds (27). Unlike actin filaments or microtubules, intermediate filaments are more elastic and resistant to strain damage (42), which may give them advantages in removing dead cells and also facilitating “cargo” delivery by DEC205 (43). Moreover, a number of pathogens have been found to be able to interact with keratins during infection (44); therefore, DEC205–keratin interactions may facilitate the antigen delivery and presentation against these pathogens.

Compared with other receptors such as CLEC9A (13, 15), PtdSerR (12), and TIM family members (16), the DEC205–keratin interaction represents a different pathway for dead cell recognition and clearance (Fig. 5H). Both keratin exposure and acidification are required for the functional activity of DEC205, which act to verify the eat-me signal on target cells or debris. As acidification is a common feature for apoptosis (45–47), it is not entirely unexpected that DEC205 could recognize keratins on dead cells in a pH-dependent fashion. Unlike other endocytotic receptors, such as mannose receptor or CLEC9A, DEC205 usually targets to late endosomes and lysosomes (14, 43); thus, DEC205 may also bind keratins on cell debris in phagosomes or early endosomes and transport them to late endosomes and lysosomes for more efficient antigen presentation. It is noteworthy that keratins are not only expressed inside cells, they are also found on the surface of some cell types such as carcinoma cells (30, 48–50). Evidence shows that extracellular acidification is usually associated with inflammation and tumorigenesis and is treated as a danger signal by the immune system (51–53). Therefore, DEC205 may be able to recognize nonapoptotic cells in these cases and act as an enhanced version among scavenging receptors in acidified regions (54, 55).

Due to the high efficiency of antigen delivery and presentation, DEC205 has been one of the major receptor targets for vaccination in dendritic-cell–based immune therapies (56, 57), and it is typically done by fusing DEC205-specific antibody with a fragment or intact protein of the antigen as a surrogate ligand (58–60). The finding of keratins as the natural ligands of DEC205 may give opportunities to improve this protocol by using ligand-fused antigens for better presentation. On the other hand, it has been shown that the abnormal expression of keratins is largely associated with tumors and may facilitate their invasion and metastasis (48–50, 61, 62). In fact, the correlation between keratins and cancer has been realized for a long time, and keratins are widely used as diagnostic markers for various tumors (20, 63). Therefore, as a specific scavenging receptor against keratins, DEC205 may have advantages over other receptors in tumor recognition and clearance, and further understanding of this pathway would provide more insights relevant to therapeutic strategies against cancer and other diseases.

Materials and Methods

Constructs encoding the ectodomain of human DEC205 (including the native signal sequence and residues 1–1,668 of the mature protein), CysR∼CTLD3 (the smaller ring, residues 1–630), FNII∼CTLD6 (the larger ring, residuals 155–1,094) were cloned into the pTT5 expression vectors with a human IgG1 Fc-tag and a C-terminal six-His tag. DEC205-GFP was also constructed with a C-terminal six-His tag into the pTT5 vectors. The supernatants of the transfected HEK293F cells were buffer exchanged with 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl at pH 8.0 by dialysis, then applied to Ni-NTA chromatography (Ni-NTA Superflow, Qiagen). The imidazole eluates were further purified by gel filtration chromatography with a Superdex 200 column. All DEC205 samples were prepared following similar procedures.

Further experimental details can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Constructs encoding the ectodomain of human DEC205 (including the native signal sequence and residues 1–1,668 of the mature protein), CysR∼CTLD3 (the smaller ring, residues 1–630), FNII∼CTLD6 (the larger ring, residuals 155–1,094) were cloned into the pTT5 expression vectors with a human IgG1 Fc-tag and a C-terminal six-His tag. DEC205-GFP was also constructed with a C-terminal six-His tag into the pTT5 vectors. The supernatants of the transfected HEK293F cells were buffer exchanged with 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl at pH 8.0 by dialysis, then applied to Ni-NTA chromatography (Ni-NTA Superflow, Qiagen). The imidazole eluates were further purified by gel filtration chromatography with a Superdex 200 column. All DEC205 samples were prepared following similar procedures. The smaller ring of mouse DEC205 (CysR∼CTLD3, residues 1–630 of the mature protein), the ectodomain of human Endo180, and the ectodomain of mouse PLA2R were also expressed and purified similarly.

The full-length human keratin 1 (1–644) and its truncation mutants (1–333, 334–644, and 334–493) were expressed in E. coli BL21 DE3 cells (Novagen) using the pET28a expression vector and purified as inclusion bodies, which were then solubilized in 8 M urea, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. The full-length human keratin 10 (1–584) and its truncation mutant (1–460) were expressed and purified similarly. The tail domain of keratin 1 (494–644) and the tail domain of keratin 10 (461–584) were also expressed similarly and purified as soluble proteins from the supernatant of E. coli cell lysates by Ni-NTA chromatography.

Apoptosis and Necrosis Assay.

Jurkat cells were cultured in 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (HyClone Laboratories). To induce apoptosis and necrosis, Jurkat cells were incubated in tissue culture flasks for several hours with 1 μg/mL actinomycin D (ActD) until use. For inducing apoptosis and necrosis of HEK293 cells, the cells were cultured in FreeStyle 293 medium including apoptosis inducers A (Apopida) [1:1,000 (vol/vol); Beyotime] for 16 h. For mouse primary cells, mouse spleens were isolated from C57BL/6 mice, then ground and dispersed through a nylon mesh (70 μm) to generate a single cell suspension. The frozen-thawed mouse cells were prepared by incubating in a dry-ice bath for 10 min and then transferring immediately into a 37 °C water bath for 10 min.

Flow Cytometry.

For the enzymatic treatment assays, the cells were washed with PBS and then treated with DNase I, RNase A, or protease K at the concentration of 10 μg/mL for 30 min, respectively. After washing twice with PBS (pH 7.4), the cells were incubated with the GFP-tagged DEC205 fragments in PBS (pH 6.0) for 20 min at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS (pH 6.0) again, the cells were analyzed by a FACS Caliber flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For keratin tail inhibition assays, the cells were washed with PBS (pH 6.0) and incubated with the GFP-tagged DEC205 fragments with or without the tail of keratin 1 or keratin 10. The concentration of keratin 1 or 10 tail fragments was about 20 μg/mL. After washing twice with PBS (pH 6.0) again, the cells were analyzed by a Becton Dickinson FACS Caliber flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The binding assays of mouse spleen cells with human DEC205-GFP and the smaller ring of mouse DEC205-GFP were performed similarly as described above. For keratin exposure assays, Jurkat cells treated with ActD were washed twice and incubated for 1 h with mouse anti-pan keratin antibody (Abcam, ab8068) or rabbit anti-keratin 1 antibody (Abcam, ab93652). Then cells were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.4), resuspended in 300 μL PBS (pH 7.4, 2.5 mM CaCl2), and incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Abcam, ab6785) or FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Abcam, ab6717), including 5 μL Annexin V-APC solution for 40 min. After washing twice by PBS (pH 7.4, 2.5 mM CaCl2) again, the cells were resuspended in 400 μL PBS (pH 6.0, 2.5 mM CaCl2) including 5 μL propidium iodide (PI) staining solution and analyzed by a LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Dot-Blot Assay.

For DEC205 ligand dot-blot assays, 2 μg of the untreated HEK293 cell lysates and the cell lysates treated individually with protease K, Endo H, or PNGase F were spotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The membranes were air dried at room temperature for 2 h and blocked in blocking buffer (PBS, 5% (wt/vol) BSA, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0) for at least 1 h. Then DEC205-Fc (10 μg/mL) was applied to the membranes and incubated with HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG Fcγ fragment-specific antibody (The Jackson Laboratory) for 1 h and detected with the DAB reagent. Between every two steps, the membranes were washed six times with washing buffer (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0) for 5 min each. To confirm the efficacy of PNGase F/Endo H treatments, 2 μg of the smaller ring of DEC205 (CysR∼CTLD3) were treated with the PNGase F or Endo H under similar conditions and analyzed by SDS/PAGE.

Lipid-Strip Assay.

Lipid strips on which the indicated phospholipids had been spotted were purchased from Echelon Biosciences. Dot-blot experiments were carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol with the blank dot (Bottom Right) spotted with 2 μg T-cell lysates. Strips were incubated overnight in a blocking buffer [PBS, 5% (wt/vol) BSA, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0] at 4 °C and then transferred into a blocking buffer containing DEC205-Fc (10 μg/mL) for 2 h at room temperature. The strips were washed three times in a washing buffer (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0) before incubating with HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG Fcγ fragment-specific antibody (The Jackson Laboratory), and the reactions were detected with the DAB reagent. For the control lipid strip experiment, the lipid strips were incubated with 2 μg/mL PI(4,5)P2 Grip (Echelon Biosciences) and detected with the DAB reagent under similar conditions.

Ligand Isolation.

Ligand isolation experiments were carried out in two independent ways. For the cross-linking experiment, DEC205 was biotinylated with NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The apoptotic HEK293 cells (∼3 × 107 cells) were incubated with the biotinylated DEC205 for 1 h in PBS (pH 6.0). After washing twice with PBS (pH 6.0), 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (pH 6.0) was added for cross-linking for 20 min and the control sample was mock cross-linked with PBS (pH 6.0). The cross-linking reactions were quenched by adding Tris buffer (2 M, pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 50 mM, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Then the cells were washed twice by PBS (pH 7.4) to remove the uncross-linked DEC205 and 2 mL RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaVO4, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, protease mixture tablet (Roche), 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS) was added for cell lysis. Cell debris was then removed by centrifugation and 25 µL of streptavidin agarose beads were added and incubated at 4 °C with rocking for 2 h. The agarose beads were then washed extensively with PBS (pH 7.4) and resuspended in 25 µL SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. The samples were loaded onto SDS/PAGE for separation and the target bands were cut out for mass spectrometry analysis.

For the direct pull-down experiment, Jurkat cells (∼5 × 107 cells) were lysed in 2 mL lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100 in PBS buffer containing protease mixture tablet (Roche), pH 6.0] for 30 min on ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min, and the insoluble material was discarded. The supernatant was split into two halves and incubated with 50 μL protein A/G magnetic beads (Biotool) preabsorbed with DEC205-Fc or Fc at 4 °C for 5 h. The magnetic beads were washed three times with washing buffer (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0) and eluted with 80 μL elution buffer (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 8.0). The eluates were analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Mass Spectrometry.

For gel sample, the gel bands were diced into small pieces and destained with CH3CN/H2O. The proteins in the gel bands were then sequentially treated with 10 mM TCEP and 55 mM IAA to reduce the disulfide bonds and alkylate the resulting thiol groups. The protein mixture was digested for 20 h at 37 °C by trypsin at 12.5 ng/μL in 50 mM NH4HCO3. The digested peptides were extracted from the gel by CH3CN/H2O, desalted with a C18 spin column. For solution sample, the samples were resolved by 8 M urea, and sequentially treated with 5 mM TCEP and 10 mM IAA to reduce the disulfide bonds and alkylate the resulting thiol groups. The mixture was digested for 16 h at 37 °C by trypsin at an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:50 (wt/wt).

The trypsin-digested peptides were loaded on an in-house packed capillary reverse-phase C18 column (15 cm length, 100-μm i.d. × 360-μm o.d. 3 µM particle size, 100 Å pore diameter) connected to a Thermo Easy-nLC1000 HPLC system. The samples were analyzed with a 180 min-HPLC gradient from 0 to 90% of buffer B (buffer A: 0.1% formic acid in water; buffer B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) at 300 nL/min. The eluted peptides were ionized and directly introduced into a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer using a nano-spray source. Survey full-scan MS spectra (from m/z 300–1,800) was acquired in the Orbitrap analyzer with resolution r = 70,000 at m/z 200. Protein identification was done with Integrated Proteomics Pipeline, IP2 (Integrated Proteomics Applications, www.integratedproteomics.com) using ProLuCID/Sequest, DTASelect2. The counts for each identified protein were calculated by adding the mass spectrometry counts of each of its detected peptides together.

ELISA Experiments.

Keratins from human epidermis (in 8 M urea) were purchased from Sigma. The keratin solution was buffer exchanged with 100 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.0) by dialysis, and then coated onto 96-well plates with ∼2 μg protein per well at 4 °C overnight. The plates were then blocked with blocking buffers [PBS with 2% (wt/vol) BSA] with different pH values at 37 °C for 3 h. Recombinant proteins were serially diluted and added to each well in a binding buffer (PBS, 2 mg/mL BSA) with preset pH values. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, the plates were washed five times with pH-adjusted PBS (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20). The bound recombinant proteins were detected by HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG Fcγ fragment-specific antibody (The Jackson Laboratory). After washing, 100 μL of chromogenic substrate (1 μg/mL tetramethylbenzidine, 0.006% H2O2 in 0.05 M phosphate citrate buffer, pH 5.0) was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C . Then, 50 μL H2SO4 (2.0 M) was added to each well to stop the reactions. The plates were read at 450 nm on a Synergy Neo machine (BioTek Instruments). For the keratin tail ELISAs, 1 μg of the purified tail fragments of keratin 1 or keratin 10 were coated onto each well of 96-well plates, then similar procedures described above were followed for the experiments.

Western Blot Assays.

Keratins from human epidermis, keratin 1 (full length or fragments) or keratin 10 (full length or fragments) expressed in E. coli were loaded onto SDS/PAGE (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with a blocking buffer [PBS, 5% (wt/vol) milk, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0 or pH 7.4] and incubated in a blocking buffer containing DEC205-Fc (10 μg/mL) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing three times (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0 or pH 7.4), the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG Fcγ fragment-specific antibody (The Jackson Laboratory) and detected with the DAB reagent.

Confocal Microscopy.

HEK293 cells grown on a coverslip were fixed and permeabilized with methanol-acetone (1:1 vol/vol) at −20 °C for 10 min. Then the cells were blocked with blocking buffer [PBS, 2% (vol/vol) FBS, 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0 or pH 7.4] for 1 h and incubated with 5 μg/mL DEC205-Fc and 2 μg/mL mouse anti-pan keratin antibody (Abcam, ab8068) or rabbit anti-cytokeratin 1 antibody (Abcam, ab93652) in the blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature. After washing three times (PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 6.0 or pH 7.4), the cells were further incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-human Fc antibody (Abcam) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Abcam) or Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Abcam). Then the cells were washed twice in the washing buffer, incubated with 5 μM DAPI for 30 min, and washed for confocal microscopy. The confocal images were acquired on a Leica SP8 microscope.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lei Han and Hongyan Wang (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology) for providing mouse spleen cells and the National Center for Protein Science Shanghai (mass spectrometry, integrated laser microscopy, electron microscopy, and protein expression and purification systems) for their instrumental support and technical assistance. This work is supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant XDB08020102), the Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant 2013CB910403), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 31270772), and the “One Hundred Talents” program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant 2012OHTP03) (all to Y.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1609331113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Poon IK, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance: Basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):166–180. doi: 10.1038/nri3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauber K, Blumenthal SG, Waibel M, Wesselborg S. Clearance of apoptotic cells: Getting rid of the corpses. Mol Cell. 2004;14(3):277–287. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: Clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(12):965–975. doi: 10.1038/nri957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravichandran KS. Find-me and eat-me signals in apoptotic cell clearance: Progress and conundrums. J Exp Med. 2010;207(9):1807–1817. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert ML, Sauter B, Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cells acquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature. 1998;392(6671):86–89. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Vliet SJ, García-Vallejo JJ, van Kooyk Y. Dendritic cells and C-type lectin receptors: Coupling innate to adaptive immune responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86(7):580–587. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, Engering A, ’t Hart BA, van Kooyk Y. Self- and nonself-recognition by C-type lectins on dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:33–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devitt A, et al. Human CD14 mediates recognition and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1998;392(6675):505–509. doi: 10.1038/33169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urban BC, Willcox N, Roberts DJ. A role for CD36 in the regulation of dendritic cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(15):8750–8755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151028698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert ML, Kim JI, Birge RB. alphavbeta5 integrin recruits the CrkII-Dock180-rac1 complex for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(12):899–905. doi: 10.1038/35046549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fadok VA, et al. A receptor for phosphatidylserine-specific clearance of apoptotic cells. Nature. 2000;405(6782):85–90. doi: 10.1038/35011084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang JG, et al. The dendritic cell receptor Clec9A binds damaged cells via exposed actin filaments. Immunity. 2012;36(4):646–657. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sancho D, et al. Identification of a dendritic cell receptor that couples sensing of necrosis to immunity. Nature. 2009;458(7240):899–903. doi: 10.1038/nature07750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahrens S, et al. F-actin is an evolutionarily conserved damage-associated molecular pattern recognized by DNGR-1, a receptor for dead cells. Immunity. 2012;36(4):635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman GJ, Casasnovas JM, Umetsu DT, DeKruyff RH. TIM genes: A family of cell surface phosphatidylserine receptors that regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;235(1):172–189. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweizer J, et al. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J Cell Biol. 2006;174(2):169–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan X, Hobbs RP, Coulombe PA. The expanding significance of keratin intermediate filaments in normal and diseased epithelia. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchs E. Keratins and the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:123–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karantza V. Keratins in health and cancer: More than mere epithelial cell markers. Oncogene. 2011;30(2):127–138. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toivola DM, Boor P, Alam C, Strnad P. Keratins in health and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;32:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang W, et al. The receptor DEC-205 expressed by dendritic cells and thymic epithelial cells is involved in antigen processing. Nature. 1995;375(6527):151–155. doi: 10.1038/375151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawiger D, et al. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194(6):769–779. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.East L, Isacke CM. The mannose receptor family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572(2-3):364–386. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West AP, Jr, Herr AB, Bjorkman PJ. The chicken yolk sac IgY receptor, a functional equivalent of the mammalian MHC-related Fc receptor, is a phospholipase A2 receptor homolog. Immunity. 2004;20(5):601–610. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y, Bjorkman PJ. Structure of FcRY, an avian immunoglobulin receptor related to mammalian mannose receptors, and its complex with IgY. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(30):12431–12436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106925108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao L, Shi X, Chang H, Zhang Q, He Y. pH-dependent recognition of apoptotic and necrotic cells by the human dendritic cell receptor DEC205. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(23):7237–7242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505924112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boskovic J, et al. Structural model for the mannose receptor family uncovered by electron microscopy of Endo180 and the mannose receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(13):8780–8787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang H, et al. Crystal structures reveal the multi-ligand binding mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus ClfB. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(6):e1002751. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samen U, Eikmanns BJ, Reinscheid DJ, Borges F. The surface protein Srr-1 of Streptococcus agalactiae binds human keratin 4 and promotes adherence to epithelial HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75(11):5405–5414. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00717-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrmann H, Aebi U. Intermediate filaments: Molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular Scaffolds. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:749–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strnad P, et al. Unique amino acid signatures that are evolutionarily conserved distinguish simple-type, epidermal and hair keratins. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 24):4221–4232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shrimpton RE, et al. CD205 (DEC-205): A recognition receptor for apoptotic and necrotic self. Mol Immunol. 2009;46(6):1229–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahoud MH, et al. DEC-205 is a cell surface receptor for CpG oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(40):16270–16275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208796109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rotty JD, Hart GW, Coulombe PA. Stressing the role of O-GlcNAc: Linking cell survival to keratin modification. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(9):847–849. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jürgensen HJ, et al. Complex determinants in specific members of the mannose receptor family govern collagen endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(11):7935–7947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinert PM, et al. Glycine loops in proteins: Their occurrence in certain intermediate filament chains, loricrins and single-stranded RNA binding proteins. Int J Biol Macromol. 1991;13(3):130–139. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(91)90037-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh EJ, O’Brien LM, Liang X, Hook M, Foster TJ. Clumping factor B, a fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) adhesin of Staphylococcus aureus, also binds to the tail region of type I cytokeratin 10. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(49):50691–50699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haim M, et al. Cytokeratin 8 interacts with clumping factor B: A new possible virulence factor target. Microbiology. 2010;156(Pt 12):3710–3721. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marceau N, et al. Dual roles of intermediate filaments in apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(10):2265–2281. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caulín C, Salvesen GS, Oshima RG. Caspase cleavage of keratin 18 and reorganization of intermediate filaments during epithelial cell apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;138(6):1379–1394. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner OI, et al. Softness, strength and self-repair in intermediate filament networks. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(10):2228–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahnke K, et al. The dendritic cell receptor for endocytosis, DEC-205, can recycle and enhance antigen presentation via major histocompatibility complex class II-positive lysosomal compartments. J Cell Biol. 2000;151(3):673–684. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geisler F, Leube RE. Epithelial intermediate filaments: Guardians against microbial infection? Cells. 2016;5(3):E29. doi: 10.3390/cells5030029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuyama S, Llopis J, Deveraux QL, Tsien RY, Reed JC. Changes in intramitochondrial and cytosolic pH: Early events that modulate caspase activation during apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(6):318–325. doi: 10.1038/35014006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gottlieb RA, Nordberg J, Skowronski E, Babior BM. Apoptosis induced in Jurkat cells by several agents is preceded by intracellular acidification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(2):654–658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lagadic-Gossmann D, Huc L, Lecureur V. Alterations of intracellular pH homeostasis in apoptosis: Origins and roles. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(9):953–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ditzel HJ, et al. Modified cytokeratins expressed on the surface of carcinoma cells undergo endocytosis upon binding of human monoclonal antibody and its recombinant Fab fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(15):8110–8115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuchma MH, Kim JH, Muller MT, Arlen PA. Prostate cancer cell surface-associated keratin 8 and its implications for enhanced plasmin activity. Protein J. 2012;31(3):195–205. doi: 10.1007/s10930-011-9388-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Godfroid E, Geuskens M, Dupressoir T, Parent I, Szpirer C. Cytokeratins are exposed on the outer surface of established human mammary carcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 1991;99(Pt 3):595–607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajamäki K, et al. Extracellular acidosis is a novel danger signal alerting innate immunity via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(19):13410–13419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.426254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lardner A. The effects of extracellular pH on immune function. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69(4):522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webb BA, Chimenti M, Jacobson MP, Barber DL. Dysregulated pH: A perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(9):671–677. doi: 10.1038/nrc3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vermeulen M, et al. Acidosis improves uptake of antigens and MHC class I-restricted presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;172(5):3196–3204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermeulen ME, et al. The impact of extracellular acidosis on dendritic cell function. Crit Rev Immunol. 2004;24(5):363–384. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v24.i5.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sehgal K, Dhodapkar KM, Dhodapkar MV. Targeting human dendritic cells in situ to improve vaccines. Immunol Lett. 2014;162(1 Pt A):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reuter A, et al. Criteria for dendritic cell receptor selection for efficient antibody-targeted vaccination. J Immunol. 2015;194(6):2696–2705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonifaz LC, et al. In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med. 2004;199(6):815–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheong C, et al. Improved cellular and humoral immune responses in vivo following targeting of HIV Gag to dendritic cells within human anti-human DEC205 monoclonal antibody. Blood. 2010;116(19):3828–3838. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhodapkar MV, et al. Induction of antigen-specific immunity with a vaccine targeting NY-ESO-1 to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(232):232ra51. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hembrough TA, Li L, Gonias SL. Cell-surface cytokeratin 8 is the major plasminogen receptor on breast cancer cells and is required for the accelerated activation of cell-associated plasminogen by tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(41):25684–25691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hobbs RP, et al. Keratin-dependent regulation of Aire and gene expression in skin tumor keratinocytes. Nat Genet. 2015;47(8):933–938. doi: 10.1038/ng.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moll R, Divo M, Langbein L. The human keratins: Biology and pathology. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129(6):705–733. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]