Summary

Electron microscopy (EM) remains the primary method for imaging cellular and tissue ultrastructure, although simultaneous localization of multiple specific molecules continues to be a challenge for EM. We present a method for obtaining multicolor EM views of multiple subcellular components. The method uses sequential, localized deposition of different lanthanides by photosensitizers, small molecule probes or peroxidases. Detailed view of biological structures is created by overlaying conventional electron micrographs with pseudocolor lanthanide elemental maps derived from distinctive electron energy-loss spectra (EELS) of each lanthanide deposit via energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM). This results in multicolor EM images analogous to multicolor fluorescence but with the benefit of the full spatial resolution of EM. We illustrate the power of this methodology by visualizing hippocampal astrocytes to show that processes from two astrocytes can share a single synapse. We also show that polyarginine-based cell-penetrating peptides enter the cell via endocytosis, and that newly synthesized PKMζ in cultured neurons preferentially localize to the post-synaptic membrane.

eTOC blurb

Multicolor electron microscopy is introduced by Adams et al. for imaging multiple, specific cellular components by locally depositing lanthanides and using electron energy-loss spectroscopy and energy-filtering EM. Analogous to multicolor fluorescence this method offers full spatial resolution of EM.

Introduction

Electron microscopy (EM) of biological samples remains the ultimate method for imaging cellular ultrastructure despite the recent advances in super-resolution microscopy (Betzig, et al., 2006; Hell, 2007; Huang, et al., 2009). Contrast in standard EM of epoxy-embedded samples is dependent upon deposition of heavy metals such as osmium, uranium or lead to highlight cellular components including protein, lipid or nucleic acid using long established and poorly selective stains. Selective visualization of specific proteins or macromolecules can be achieved using antibodies conjugated to gold particles or quantum dots of distinctive size, but poor penetrability of such labels in fixed cells or tissues limits the use of optimal fixation methods that preserve ultrastructure (Schnell, et al., 2012). This limitation can be avoided by the in situ oxidation of diaminobenzidine (DAB) generating a localized osmiophilic precipitate by photosensitizing dyes conjugated to antibodies or ligands (Deerinck, et al., 1994; Maranto, 1982), genetically targeted biarsenicals (Gaietta, et al., 2002) and genetically encoded chimeras of miniSOG (Shu, et al., 2011). Peroxidases (such as horse radish peroxidase, HRP) also generate similar precipitates from DAB on treatment with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and robust genetically-encoded versions have been developed recently (Kuipers, et al., 2015; Lam, et al., 2015; Martell, et al., 2012). The high penetrability of small dyes, DAB, and oxygen or H2O2 into optimally fixed cells or tissues enables specific labeling with preservation of cellular ultrastructure. The target protein becomes negatively-stained by the surrounding oxidized DAB precipitate, which may not be readily distinguishable from heavy staining from endogenous cellular structures such as membranes and the post-synaptic density.

In this work, we demonstrate a method (Figure 1A) that can differentiate the DAB precipitate from the general staining of endogenous cellular material and permits identification and imaging of successively deposited DAB, each at a targeted or specified protein or cellular target. By precipitating DAB conjugated to lanthanide chelates rather than DAB itself, a specific metal such as Ce3+ is locally deposited. After washing out the unreacted DAB-chelator-Ln, a further round of deposition of DAB-chelator bound to another lanthanide ion such as Pr3+ is carried out by photooxidation of a second photosensitizer targeted to another cellular site or protein, at wavelengths that do not excite the first fluorophore. Alternatively, peroxidases can be used to generate the second precipitate. Following conventional postfixation staining with osmium tetroxide and electron microscopy of sections from embedded samples, the two precipitates containing different tightly-bound lanthanide ions can be spectrally separated using spatially-resolved electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS), which is implemented by energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM). Elemental distribution maps for the two metals obtained by EFTEM reveal their spatial distribution, and can be overlaid as pseudocolors on the conventional black-and white electron micrograph to give a multicolor image superimposed on cellular ultrastructure. The method is also useful for only a single deposited lanthanide, because the EELS signal is not obscured by staining of endogenous cellular structures by osmium or other heavy metals used for contrast in EM.

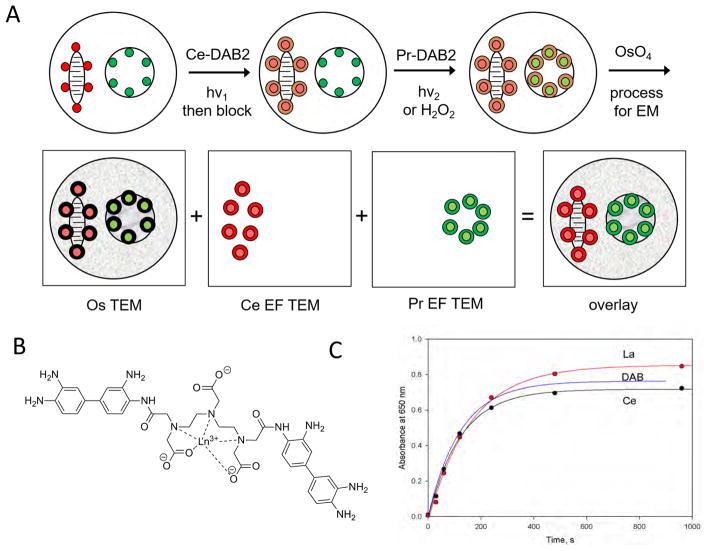

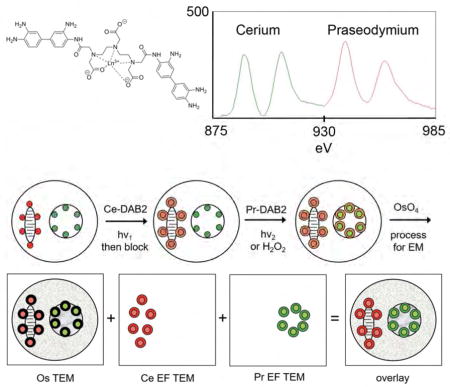

Figure 1. Two-color EM using EELS and EFTEM.

(A) Scheme of process applied to cells with stained mitochondrial (red) and nuclear membranes (green) are first selectively irradiated to photooxidize the red photosensitizer and precipitate Ce-DAB2 (brown ring). After washing and replacement with Pr-DAB2, illumination at an orthogonal wavelength generates precipitate at the nuclear membrane. Alternatively, the Pr-DAB2 can be oxidized by hydrogen peroxide following immunoperoxidase labeling. Following conventional osmification (black ring), embedding, sectioning and TEM, EFTEM yields pseudocolored elemental maps for Ce and Pr that are overlaid on the conventional osmium image (B) Structure of Ln-DAB2 (C) La- and Ce-DAB2 are precipitated at a similar rate to DAB by photosensitization of eosin

Results

Synthesis of DAB-metal chelate conjugates

In designing metals complexed to DAB that would precipitate on oxidation, we considered the following requirements. The metal ions should have strong, distinct EELS peaks that are simultaneously quantifiable, and must form high affinity chelates to prevent any loss of metal ions during DAB oxidation and subsequent processing leading to a decreased EELS signal or a false positive signal. The lanthanide series have a similar charge (3+), ionic radii, and suitable EELS signals and should bind to a conjugate of DTPA with two DAB (Figure 1B) with three carboxylates to form a high-affinity complex (dissociation constants of 0.1–1 fM for Gd3+ have been reported for related DTPA-bisanilides) (Geze, et al., 1996) with overall neutral charge to facilitate precipitation. The DTPA-DAB2 was synthesized by the reaction of DTPA anhydride with a five-fold excess of DAB to hinder the formation of polymers (Figure S1). Following removal of most of the unreacted DAB by extraction, the product DTPA-DAB2 was precipitated. This solid was used for all subsequent photooxidation experiments with DTPA-DAB2 despite containing some unreacted DAB and monomer DTPA-DAB as measured and quantified by LC-MS (Figure S2). When free DAB was removed from the material by HPLC, the purified DTPA-DAB2 generated less precipitate in cuvette experiments and failed to generate the expected localized precipitate in cells (data not shown).

Metal binding to lanthanides and precipitation of metal complex on oxidation

The complexation of DTPA-DAB2 to lanthanide ions, Ln3+, was measured by titration using arsenazo III as a colorimetric indicator to the end point and by comparison to an equal concentration of DTPA. Each batch synthesized gave between 75–85% purity by weight from titration assuming the expected 1:1 stoichiometry and closely matched the percent purity of DTPA-DAB2 measured by HPLC (Figure S2). Precipitation of this so formed Ln DTPA-DAB2 (Ln-DAB2) following photooxidation by photosensitization of eosin at 480 nm was measured by monitoring the absorbance from increasing scattering at 600 nm (Deerinck, et al., 1994; Natera, et al., 2011). Typical time courses for La-, Ce-, Pr-, Nd-, and Sm-DAB2 were similar to that of DAB (Figure 1C) and were in contrast to greatly decreased precipitate when no lanthanide was present, confirming the requirement of charge neutralization for efficient precipitation (data not shown). All the Ln-DAB2 tested showed limited solubility in 100 mM sodium cacodylate pH 7.4, the buffer conventionally used for photooxidation in fixed cells and tissues and optimal for preserving ultrastructure in EM. To achieve a concentration close to the 2.5 mM value typically used for DAB, 2.5% DMF was added as a co-solvent and the cacodylate buffer concentration was decreased to 50 mM. The final metal ion concentrations following filtration were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy to be about 0.8 mM with about 2 mM total DAB content (DTPA-DAB2 and DAB) as measured by absorbance at 309 nm using an extinction coefficient of 14200 M−1cm−1.

Two-color EM of tissue culture cells

We next tested whether two Ln-DAB2 could be orthogonally precipitated in cells and whether the specific EELS signals of the two metals could be detected and separated as elemental images. Madine-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells stably expressing green fluorescent protein fused to epithelial cell adhesion molecule (GFP-EpCAM), were initially stained with NBD-ceramide, a Golgi-selective fluorescent probe capable of photosensitizing DAB (Pagano, et al., 1991; Pagano, et al., 1989; Takizawa, et al., 1993), and then subsequently an antibody to the cell surface marker, EpCAM (Schnell, et al., 2013), followed by a biotinylated secondary antibody. Following mild fixation, irradiation at 535 nm in the presence of La-DAB2 and oxygen gave faint darkening from formation of reaction product in cell regions corresponding to the fluorescence image of NBD-ceramide. The cells were treated with acetic anhydride to block any unreacted amines of the DAB moiety of the reaction product to prevent further reaction of the deposited precipitate. Ce-DAB2 was then precipitated after further labeling of EpCAM sites by HRP-streptavidin and incubation with hydrogen peroxide. Following osmification, resin embedding and sectioning, a low- magnification unfiltered electron micrograph (Figure 2A) of a typical cell reveals the expected intracellular and plasma membrane staining from deposited precipitates at the Golgi and cell surface. However, EELS of regions at the Golgi or plasma membrane (circled in Figure 2A) revealed characteristic peaks from predominately La or Ce (Figure 2B) respectively. The small contaminating Ce signal at the Golgi probably resulted from unwanted deposition of Ce-DAB2 at the site of previously photooxidized Ln-DAB2 despite acetylation of any residual free amines, and could be mathematically subtracted in the EELS spectra (Figure 2B′), and the elemental maps for La and Ce (Figure 2C, D, D′). To do this we selected a region in the field being observed that was expected to only contain La such as the Golgi and integrated the La and Ce peaks in this area’s EELS spectrum to give the fraction of contaminating Ce in the La channel that was then subtracted from the La elemental map. These core-loss elemental maps were generated by subtraction of four images (two pre-edge and two after-peak images, see experimental procedures for details) rather than two with the traditional three-window method (Egerton, 1996), to minimize any effects of signal bleed-through of the lanthanides resulting from inaccurate background extrapolation. To reduce sample warping and drift, we found taking multiple short image acquisitions and carbon coating the sample were greatly beneficial. This five-window method shows distinct signal from the appropriate cell regions with La at the Golgi and Ce at the plasma membrane.

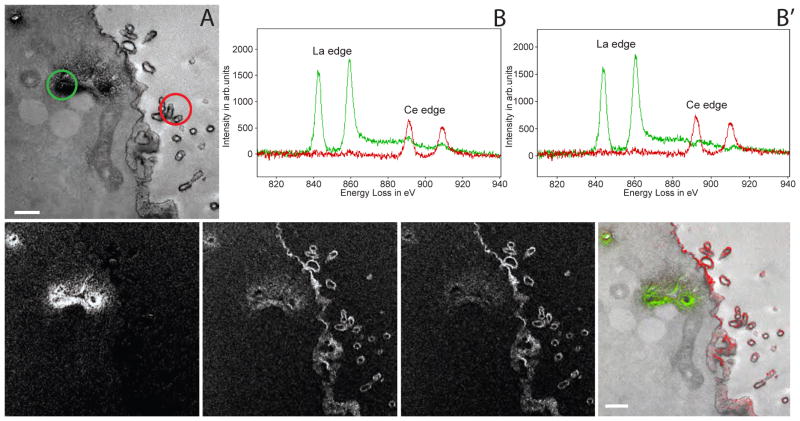

Figure 2. Two color EM of Golgi and plasma membrane in tissue culture cells.

(A) Conventional TEM image (x 6000, 1.4 nm/pixel) of MDCK cell following photooxidation with La-DAB2 by NBD ceramide-labeled Golgi and subsequent oxidation of Ce-DAB2 on plasma membrane (PM) with HRP-labeled antibody to EpCAM. (B) Spectra obtained at Golgi region (green spectra), and at PM containing EpCAM (red spectra); the respective regions are shown as circles in A. The Golgi region shows a strong La signal with weak Ce signal, the PM region shows only Ce. (B′) The cross-talk in the spectra shown in B, due to Ce-DAB2 attaching to regions labeled with La-DAB2 has been mathematically subtracted. (C) & (D) La and Ce elemental map obtained by the five-window method on the CCD (bin by four pixels), each energy window image was a sum of nine individual drift corrected images, each acquired for a 60 s exposure. A Gaussian smoothing of blur radius 1 was applied to the images. (D′) The Ce map shown in D, mathematically corrected to remove the cross-talk due to Ce-DAB2 attaching to regions labeled with La-DAB2. (E) Two color merge of the elemental maps (La in green and Ce in red), overlaid on the conventional TEM image.

How should the two energy-filtered lanthanide maps and conventional TEM be visually combined? We first tried “mixing” in Photoshop the conventional TEM in grayscale (normal or inverted) with the lanthanide maps in red and green respectively. However, the grayscale image tended to drown out the color images because the black pixels stayed black regardless of any colors mixed in (Figure S3A–E). Next we tried displaying the conventional TEM in blue, so that a region with strong La-DAB2 or Ce-DAB2 would appear cyan or magenta respectively (Figure S3F, G). Unfortunately, regions with conventional TEM only tend to suffer because of the low psychophysical visibility of the blue channel. Assigning green to the conventional TEM and blue to the Ce-DAB2 de-emphasized the latter too much and merely shifted the problem. Finally, we realized that the conventional TEM image has high spatial frequencies, resolution, and S/N, analogous to the luminance channel in television, whereas the colors should be displayed as lower-resolution overlays, effectively modulating the alpha channel for transparency vs. opacity. Therefore, we used a custom algorithm to generate pseudocolored overlays of the La and Ce elemental maps on the monochrome unfiltered osmium image (conventional EM image) to yield a two-hue representation of marker distribution with the resolution of an electron micrograph (Figures 2E, S3H). An advantage of this algorithm is that it can be generalized to three or more pseudocolor channels.

Hippocampal astrocyte cell tracing in brain slices

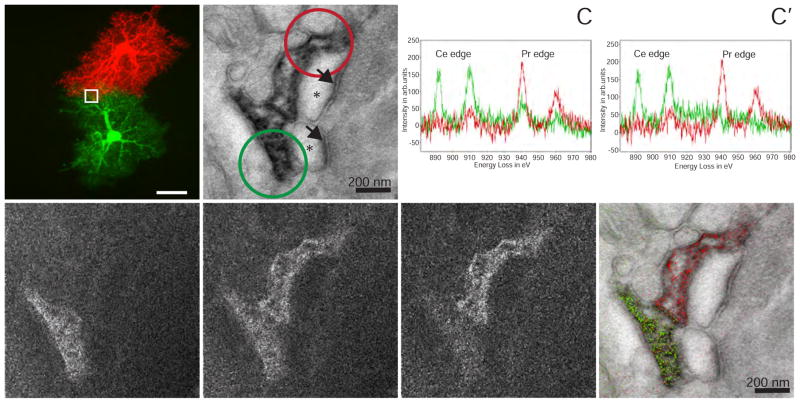

Following this proof of principle, we tested this method’s application to biological questions that required the ultrastructural resolution of EM and labeling of two cell markers. Protoplasmic astrocytes in the mouse hippocampus establish distinct territories with limited overlap between peripheral processes. These fine peripheral processes intimately contact and modulate neuronal synapses (Haydon, 2001; Haydon and Carmignoto, 2006). Whether synapses located at domain boundaries are shared by two astrocytes is unknown as both synaptic profiles and the fine astrocytic processes near synapses are generally beyond the resolution limit of light microscopy (Bushong, et al., 2004; Bushong, et al., 2002; Halassa, et al., 2007). We injected two adjacent astrocytes in fixed hippocampal slices with either Lucifer yellow or a combination of Alexa-568 and neurobiotin (Figure 3A). Ce-DAB2 was photo-oxidized by Lucifer yellow at 470 nm. Acetyl imidazole was used to passivate the Ce-DAB2 precipitate instead of acetic anhydride because of its greater stability at neutral pH, higher solubility in water and self-buffering at pH 5 that favors reaction with the aromatic amines of DAB (Oakenfull and Jencks, 1971). Then neurobiotin was captured with HRP-streptavidin, which in turn was reacted with Pr-DAB2 and H2O2. After osmification and embedding in resin, sections were examined by EM for synapses with surrounding densely-stained astrocyte processes containing both Ce and Pr signals by EELS. An example of a perforated synapse with clearly defined synaptic cleft and pre- and post-synaptic components marked by synaptic vesicles and postsynaptic densities respectively is shown in Figure 3B. EELS of sub-regions of each of the two astrocytic processes contacting the synapse revealed predominately Ce or Pr signals (Figure 3C). Some signal from Pr is still present in the Ce astrocyte, perhaps from incomplete inactivation of the first Ce-DAB2 precipitate by limited penetration of the acetyl imidazole into the fixed brain slice. The individual elemental maps (Figure 3D, E, and corrected Pr map, 3E′) and their overlay with an unfiltered EM (Figure 3F) also indicate the processes from two astrocytes can share a single synapse.

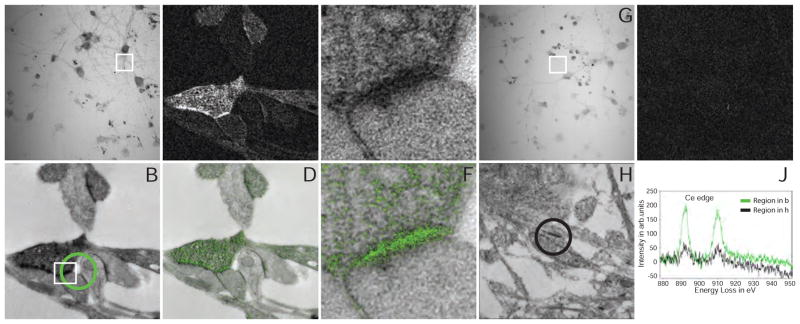

Figure 3. Two-color EM of hippocampal astrocytes in brain slices.

(A) Correlative fluorescent image of adjacent hippocampal astrocytes injected with Lucifer yellow or neurobiotin/Alexa 568. The white box is the approximate region of the EM acquisition, shown in the following panels. (B) Conventional TEM image (x 15000, 0.56 nm/pixel) showing astrocyte processes containing precipitated Ce- and Pr-DAB2 complexes contacting two spines synapsing (asterisk) with a bouton (PSDs indicated with arrows). (C) EELS spectra obtained at the lower astrocyte (green spectra) photooxidized with Ce-DAB2 and upper astrocyte (red spectra) HRP enzymatically reacted Pr-DAB2; the respective regions are shown as circles in B. The upper astrocyte contains predominately Pr, whereas the bottom has Pr and Ce signals. (C′) The cross-talk in the spectra shown in C, due to Pr-DAB2 attaching to regions labeled with Ce-DAB2 has been mathematically subtracted. (D) & (E) Ce and Pr elemental maps (x 25000; five window method using a sum of 19 drift-corrected 50 s exposures per window). (E′) Corrected Pr map, removing Pr-DAB from regions with Ce-DAB. (F) Two-color merge of the spectrally-separated elemental maps (green for Ce and red for Pr) overlaid on a conventional image, showing the two different astrocyte processes contacting the same synapse.

Endosomal uptake of cell-penetrating peptides

We next explored whether it is feasible to precipitate Ce- and Pr-DAB by successive irradiation of two spectrally distinct photo-sensitizers rather than photooxidation followed by HRP-mediated oxidation. We first generated Ce-DAB2 precipitate by 480 nm irradiation of nuclear targeted miniSOG (Shu, et al., 2011) and then tested the ability of ReAsH-labeled tetracysteine-tagged connexin 43 that form gap junctional plaques (Gaietta, et al., 2002), to photo-oxidize DAB2 when excited at 560 nm. Pr-DAB2 was precipitated as expected at the plasma membrane but also in the nucleus suggesting the initial precipitate itself could act as a photosensitizer of DAB (data not shown). Ce-DAB2 photo-oxidized in a cuvette shows a broad absorbance centered at 500 nm that extends to 600 nm, and correspondingly in cells we found that after nuclear deposition of Ce-DAB2 by mini-SOG at 480 nm, irradiation at >630 nm would not precipitate Pr-DAB2. ReAsH does not absorb at 630 nm, so we tested the ability of far-red photosensitizers such as the phthalocyanine dye, IRDye 700DX (Mitsunaga, et al., 2011; Peng, et al., 2006) to photo-oxidize Pr-DAB2.

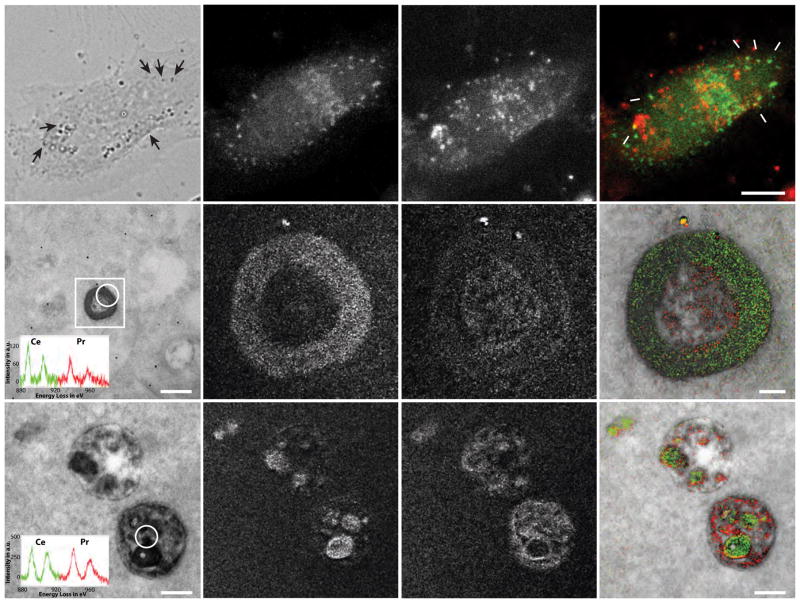

Cell penetrating peptides (CPP), including oligomers of cationic amino acids like arginine (n=9–14), have been extensively used to deliver membrane-impermeant molecules or particles into the cytoplasm of cells (Copolovici, et al., 2014). CPPs rapidly bind to the plasma membrane and are hypothesized to enter cells via endocytosis (Brock, 2014; Kaplan, et al., 2005; Richard, et al., 2003). To determine whether poly-arginine CPPs enter cells via the endocytic pathway, we examined the localization of an internalized Arg10 peptide compared to Rab5a, a small GTPase that localizes to endosomal membranes, at a scale too small to resolve using conventional light microscopy. We incubated HeLa cells expressing Rab5a fused to miniSOG (Shu, et al., 2011) with an Arg10 peptide conjugated to IRDye 700DX photosensitizer (Figure S4) that can polymerize DAB. After the cells were incubated with Arg10-IRDye 700DX peptide for two hours, they were fixed and imaged by light microscopy (Figure 4). We detected bright intracellular puncta from the endocytosed Arg10-IRdye 700DX peptide (Figure 4C) that partially co-localized with miniSOG fluorescence (Figure 4B, D). We then irradiated the sample at 480 nm to photo-oxidize Ce-DAB2 catalyzed by miniSOG, removed unreacted Ce-DAB2 by washing, blocked amines with acetyl imidazole, and then illuminated at 680 nm to photo-oxidize Pr-DAB2 catalyzed by IRdye 700DX. Both endosomes and multivesicular bodies (MVB) were photo-oxidized and visible in the unfiltered EM and both contain precipitated Ce and Pr by EELS (Figure 4E and I respectively). The elemental maps and overlay with conventional EM image (Figure 4F–H) indicate that Ce is concentrated on the endosome periphery in accordance with the expected cytoplasmic localization of Rab5a, whereas Pr is predominately in the endosome lumen. In this example, we could not correct the Ce channel for contaminating Pr as EELS spectra with adequate signal-to noise could not be obtained solely for endosomal lumen or the periphery. The corresponding images of MVB (Fig. 4J–L) also show a similar distribution of Ce and Pr but with less cytosolic Ce, and several densely Ce-stained luminal vesicles formed by inward budding of the endosomal membrane. Endosomal localization of Rab5a has been shown to progressively decrease during early endosome maturation to MVB (Rink, et al., 2005) which is in agreement with our results. In addition, Arg10-IRdye 700DX colocalization with Rab5a in intracellular vesicles confirms that polyarginine-based CPPs enter the cell via endocytosis.

Figure 4. Two-color EM of endosomal uptake of CPPs.

(A) Transmitted light image of miniSOG-Rab5a transfected HEK293 cell treated with Arg10-IRDye 700DX showing endosomes (arrows) following photooxidation. Corresponding fluorescent images of (B) miniSOG-Rab5a, (C) Arg10-IRDye 700DX labeling and (D) two-color overlay of fluorescent images with typical endosomes arrowed. (E) Conventional TEM image (x 20000, 0.45 nm/pixel) of an endosome after consecutive photo-oxidization of Ce-(miniSOG-Rab5a) and Pr-DAB2 (Arg10-IRDye 700DX). The inset is the EELS spectrum from the circled region and the rectangular box is the region of elemental map acquisitions, shown in the subsequent panels. (F) and (G) Ce and Pr elemental maps respectively of endosome (x 25000, 0.2nm/pixel; five-window method using a sum of 12 drift-corrected 50 s exposure per window, smoothed with Gaussian blur radius 3). (H) Two-color merge of the Ce (green) and Pr (red) elemental maps overlaid on the TEM image reveals the Arg10 is lumenal and Rab5a is on the cytoplasmic face of the endosome. (I) TEM image (x 20000, 0.45 nm/pixel) of a MVB from the same cell with the EELS spectrum of the circled region inset. (J) & (K) Ce and Pr elemental maps respectively of the MVB (x 20000, 1.8 nm/pixel; five-window method on CCD detector (bin by four pixels) using a sum of six drift-corrected 40 s exposures, smoothed with Gaussian blur radius 1). (L) Two-color merge of the Ce (green) and Pr (red) elemental maps), overlaid on TEM image showing vesicular but no cytoplasmic Rab5a.

Tracking newly-synthesized PKMζin cultured neurons

Finally, we used EELS analysis of a single lanthanide-conjugated DAB to confirm DAB-based labeling that is not readily distinguishable from background with conventional TEM, particularly in regions that are normally electron dense such as the neuronal post-synaptic density. The kinase PKMζ has been implicated in long-term memory maintenance and is upregulated following neuronal activity (Shao, et al., 2012), but the function and precise sub-synaptic localization of these new PKMζcopies is unclear. We fused PKMζcDNA to a TimeSTAMP reporter, TS:YSOG3 (Palida, et al., 2015) that contains both YFP and miniSOG and allows newly synthesized proteins to be labeled in a drug-dependent manner using the small molecule BILN-2061. New copies can be visualized by correlated light and electron microscopy in a manner similar to previous TimeSTAMP reporters incorporating a split YFP and miniSOG (Butko, et al., 2012) (Figure S5). We induced chemical long term potentiation (LTP) by stimulating TS:YSOG3-PKMζ-transfected rat neurons in culture with forskolin and rolipram and then immediately added BILN-2061 for 24 hours to label newly-synthesized copies of PKMζ. These new copies were visible by YFP fluorescence and then were illuminated so that miniSOG would catalyze photooxidation of Ce-DAB2. After osmification, darkening was visible throughout the neuron at low magnification (Figure 5A) and labeling appeared at postsynaptic membranes in TEM (Figure 5B), yet it was unclear whether this signal was derived from DAB deposition or endogenous synaptic electron density. To confirm that the apparent signal was representative of newly produced PKMζprotein, we used EELS to visualize Ce at the same synapse. We found that the Ce signal was enhanced at the postsynaptic membrane (Figure 5C and D at lower magnification, E and F at higher magnification) confirming that new copies of PKMζpreferentially localize to the post-synaptic membrane, consistent with previous reports for PKMζlocalization (Hernández, et al., 2014). Unstimulated neurons that were treated with BILN-2061 and analyzed similarly (Figure 5G–I) showed only a minimal signal for Ce by EELS in synapses (Figure 5J) despite comparable post-synaptic density staining in conventional EM.

Figure 5. Chemical LTP results in PKMζlocalization to the postsynaptic membrane.

(A) Transmitted light image of photooxidized cultured neurons expressing TS:YSOG3-PKMζ, stimulated with forskolin and rolipram, treated with BILN-2061 for 24 hours, and photo-oxidized with Ce-DAB2. (B) TEM image (x 6000, 0.9nm/pixel) of a neuron (white box in A) showing enhanced post-synaptic electron density. (C) Ce elemental map (x 8000, 4.4 nm/pixel; three-window method using a sum of seven drift-corrected 40 s exposures per window, smoothed with a Gaussian blur 1) showing that Ce localization corresponds to photooxidation and confirming that PKMζstrongly localizes to the postsynaptic membrane after stimulation. (D) Overlay of Ce map (green) on the TEM image. (E) TEM image at a higher magnification of the region shown in B (white box). (F) Overlay of Ce map at higher magnification (x 25000, 0.2 nm/pixel; three-window method using a sum of 25 drift-corrected 50 s exposures per window, smoothed with Gaussian blur 3) on the TEM image. (G) Transmitted light image of unstimulated neurons expressing TS:YSOG3-PKMζtreated with BILN-2061 for 24 hours and photo-oxidized with Ce-DAB2. (H) TEM image of neuron shown in G (white box). (I) Ce elemental map (x 8000, 4.4nm/pixel; three-window method using a sum of seven drift-corrected 40 s exposures per window, smoothed with a Gaussian blur 1, of the region in H scaled similarly to C indicating minimal Ce deposition and that basally produced TS:YSOG3-PKMζis not post-synaptically localized in the image. J) EELS quantification of the relative Ce signal spectra of the circular regions shown in B (green circle) and H (black circle), normalized to the same background counts.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a method that permits concurrent and selective visualization by EELS and EFTEM of two cellular components that can be labeled by photosensitizing fluorescent tracers or by peroxidases that can oxidize Ln-DAB2. Many fluorescent dyes are known to generate sufficient singlet oxygen via triplet sensitization of molecular oxygen so the method should be of wide scope. The use of genetically-encoded singlet oxygen generators, such as miniSOG when fused to proteins of interest, also permits the selective visualization by fluorescence and correlated EFTEM of their cellular localization in samples ranging from tissue culture cells to complex tissues such as the mammalian brain. Ln-DAB2 is efficiently precipitated by HRP for immunoperoxidase labeling but with some limitations. Unexpectedly, we found that HRP or its genetically-encoded versions and the more recently developed APEX (Lam, et al., 2015; Martell, et al., 2012), a mutated ascorbate peroxidase, act as photosensitizers and precipitate Ln-DAB2 (or DAB) when illuminated between 400–650 nm (data not shown). This property limits their use with multicolor EM unless they are introduced after the first round of Ln-DAB2 photooxidation as described above (Figures 2 and 3). Both peroxidases contain a heme prosthetic group that has not been reported to photosensitize molecular oxygen but if insufficient heme is available in the cell, protoporphyrin IX (Durner and Klessig, 1995) is known to bind both HRP and APEX (Jullian, et al., 1989; Lam, et al., 2015; Martell, et al., 2012). We speculate that trace bound amounts of this efficient photosensitizer (Fernandez, et al., 1997) are responsible for the photooxidation of Ln-DAB2 by these enzymes over the range of illuminating wavelengths that match that of protoporphyrin IX absorbance. APEX2 was engineered to improve heme binding but still deposited DAB upon illumination. Chemical inactivation (Durner and Klessig, 1995) of APEX2 to permit a second Ln-DAB2 to be photo-oxidized by another photosensitizer was ineffective. Further mutation of APEX or methods for increasing cellular heme availability during APEX expression will probably be required for their use in multicolor EM. Despite these limitations, multicolor EM has demonstrated the feasibility of selective deposition of metals by DAB oxidizers that are organelle stains, genetically-targetable or encodable, or immunoreactive. EFTEM although predominately used today for chemical analysis of materials, has been applied to biological samples, using the generally weak signals from endogenous elements (Aronova and Leapman, 2012), but is sufficiently sensitive to detect and distinguish many of the fourteen stable lanthanides when precipitated as Ln-DAB2. The sensitivity of the method is probably not limited by Ln-DAB oxidation as it photooxidizes at a comparable rate to DAB which can yield close to single-molecule detectability after extended illumination, staining with osmium and conventional TEM (unpublished results). There is negligible Ln background signal in EELS spectra of non-photooxidized cells so similar sensitivity might be expected, but EELS is an inherently insensitive technique. The major current limitation is probably the noise introduced by sample drift during the long energy-filtered exposures required for the images.

Improvements are underway to boost the sensitivity of multicolor EM by increasing the amount of lanthanide that is deposited during the oxidation of Ln-DAB chelates. Further development should lead to a greater understanding of the relationship between structure and metal deposition and will improve signal-to-noise, decrease acquisition time and sample damage, and potentially permit greater resolution through tomography. The use of DAB to precipitate metals limits the scope of photooxidation because the polymer itself acts as a photosensitizer of further DAB oxidation up to about 600 nm, and limits the number of different Ln-DABS that can be successively deposited by spectrally distinct photosensitizers. Acylation of unreacted amino groups in the Ln-DAB precipitate diminished its undesired reaction with a subsequent Ln-DAB Efforts are underway to completely chemically block it and the photosensitizing effects of precipitated Ln-DAB, and thereby eliminate the present requirement for deconvolution that can be problematic when the elemental signals are all co-localized

Significance

Major improvements in multicolor and super-resolution fluorescence microscopy over the last two decades’ have dramatically improved our understanding of cellular microarchitecture and function. Comparable progress in electron microscopy has been achieved in throughput and automation but methods for marking multiple molecules of interest has been more limited. This work describes a new methodology for such selective detection or painting by sequential localized oxidation and precipitation of diaminobenzidine conjugates of Ln chelates by genetically-encoded photosensitizers, small molecule probes or peroxidases. Electron energy- loss spectroscopy of these orthogonally deposited lanthanide metals and their imaging by energy- filtered transmission electron microscopy yields elemental maps that can be displayed on conventional electron micrographs as color overlays.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents and solvents were from Sigma-Aldrich and cell culture reagents and probes were obtained from Life Technologies except where noted. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Diego.

Synthesis of Ln-DAB2

Diethylene-triamine-N,N′,N″-triacetic acid bis(diaminobenzidine)amide, DTPA-DAB2: DTPA bis-anhydride (3.33 g, 9.33 mmol) suspended in dry DMF (33 ml) with triethylamine (1.30 ml, 9.33 mmol) under N2 was gently heated and bath sonicated until dissolved. After cooling to room temperature the solution was added dropwise over 30 min with stirring under N2, to diaminobenzidine (10 g, 46.65 mmol) and triethylamine (18.66 mmol, 2.60 ml) dissolved in dry DMF (33 ml). After stirring overnight at room temperature, the reaction mix was evaporated, dissolved in water (100 ml) and adjusted to pH 8 with 1N-NaOH until the pH stabilized (about 15 min). The mixture was stirred under N2 for one hour and then unreacted DAB was removed by filtration followed by extraction with EtOAc (3 × 100 ml). The aqueous layer was partially evaporated to remove EtOAc and then acidified to pH 5. 4 with conc. HCl to give the product as a gray precipitate which was collected by filtration and washed with water. Drying over P2O5 in vacuo overnight gave 2.75 g (38%) of a gray solid that was used without further purification. LC-MS indicated 70–80% purity with unreacted DAB as the remainder (Figure S2.)

Ln-DAB2 solutions

Ln-DAB2 solutions in cacodylate buffer were prepared immediately before use at room temperature. To make 10 ml of a 2 mM Ln, Ce or Pr-DAB2 solution, 15.6 mg (20 μmol) of DTPA-DAB2 were suspended in DMF (0.25 ml) and sonicated/vortexed to disperse. Water (8.33 ml) was added to give a cloudy solution that cleared on addition of LnCl3 aqueous solution (0.1 M of LaCl3.6H2O, CeCl3.6H2O, PrCl3.xH2O; the latter stock solution was dissolved in 0.1M HCl) with 120 μl (of La or Ce solutions) or 140 μl (of Pr solution) followed by vortexing and bath sonication to give clear light brown solutions. Aqueous NaOH solution (1 M) was added sequentially in six equal portions (6 × 10 μl) with vortexing after each addition. A precipitate was initially formed during the early steps of this neutralization but a mostly clear solution was present by the end. Cacodylate buffer (1.67 ml of 0.3 M of sodium cacodylate pH 7.4) was added, mixed and centrifuged (3000g, 10 min) to remove any precipitate. Solutions were syringe-filtered (0.22 μm, Millipore) immediately prior to addition to cells. Metal ion concentrations were measured by inductively-coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (Agilent 7700)

Synthesis of Arg10-IRDye 700DX

Arg10-IRDye 700DX was prepared by reaction of H2N-GGRRRRRRRRRR-CONH2 (where G and R are L-glycine and L-arginine respectively; synthesized by standard Fmoc chemistry with a Protein Technologies Prelude peptide synthesizer), with IRDye 700DX NHS ester (LICOR) in DMSO and N-methylmorpholine as base. The conjugate was purified by reverse-phase HPLC and characterized by LC-MS. Found, 575.0 (M+6H+), 689.6, (M+5H+), 861.9 (M+4H+), 1148.8 (M+3H+). Deconvolved to 3343.6, calc’d 3443.5.

Eosin-sensitized photooxidation

A solution of DAB or Ln-DAB2 (0.4 mM, diluted from freshly-prepared 100 mM stock solutions in DMF) and eosin (20 μM) in 100 mM sodium MOPS pH 7.2, or 0.1M sodium cacodylate pH 7.4 in a 3-ml cuvette was irradiated at 480 nm (30 nm band pass) using a solar simulator (Spectra-Physics 92191–1000 solar simulator with 1600 W mercury arc lamp and two Spectra-Physics SP66239–3767 dichroic mirrors to remove infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths). Remaining light was filtered through 10-cm square bandpass filters (Chroma Technology Corp.) with a deflector mirror set at 45° while bubbling with air. At set time points, the absorbance of the reaction was measured at 650 nm until the increase was complete.

Cell culturing, labeling and transfection

MDCK and HEK293 cells were cultured on poly-d-lysine coated 35-mmm glass bottom dishes (MatTEK) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS. MDCK Cells were labeled with 5 μM NBD C6-ceramide in media containing 10% fetal calf serum for 30 min, washed, and incubated for 30 mins in new culture media, all at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide, then washed (x5) with HBSS at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with mouse monoclonal EpCAM antibody (KS1/4) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:1000 dilution for 12 min at 37°C in HBSS, washed with HBSS, incubated for 60 min in secondary antibody biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson, 115–065–003) at 1:250 dilution at 37°C in HBSS and then washed. HEK293 cells were transfected with a miniSOG-Rab5a plasmid at 60–80% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000, which was removed after 8 hours. Cells were treated 48 hours after transfection with 2 μM Arg10-IRDye 700DX (prepared in distilled water) and added to the culture media for 2 hours at 37 °C, after which time the media was removed and cells were rinsed once in HBSS. Primary mouse cortical neurons were cultured, transfected with TS:YSOG3-PKMζ, and chemically stimulated with 50 μM forskolin and 0.1 μM rolipram for 10 min, then incubated with 1 μM BILN-2061 as previously described (Palida, et al., 2015).

General procedure for photooxidation and HRP reaction of Ln-DAB2

Labeled cells were fixed and blocked (Shu, et al., 2011). Samples were then transferred either to a Bio-Rad MRC1024 with a Zeiss Axiovert 35M microscope or a Leica SPE microscope. MDCK cells stained with NBD C6-ceramide and transfected HEK293 cells exhibiting peptide uptake were identified either by NBD C6-ceramide, or miniSOG, and IRDye 700DX fluorescence respectively, and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Freshly prepared and filtered La-DAB2 (2mM) or Ce-DAB2 (2 mM) for the first photooxidation reaction was added to the dish of cells for five min while a stream of pure oxygen was gently blown continuously over the solution. Cells were irradiated to excite NBD C6-ceramide depositing La-DAB2 or miniSOG depositing Ce-DAB2 reaction product both using 450–490 nm excitation (Ex) and 515 nm emission (Em) long-pass (LP) filters with a 580 nm dichroic mirror. Reaction product formation was monitored by transmitted light microscopy and illumination was stopped as soon as a light brown reaction product appeared. Acetic anhydride (MDCK cells) was added (20 × 20 mM freshly prepared) for 1 min each to block precipitated La-DAB2.

Alternatively, MDCK cells were rinsed 3×5 min with fresh 100 mM acetyl imidazole in 0.15 M NaCl to prevent further polymerization of either La-DAB2 or Ce-DAB2, then treated with freshly prepared Ce-DAB2 (2 mM) for HRP enzymatic reaction or irradiated to excite IRDye 700DX (Ex 675/67nm, Em, 736 LP) depositing Pr-DAB2 reaction product. Cells were rinsed 5 × 2 min, post-fixed, dehydrated, infiltrated and embedded as previously described (Shu, et al., 2011).

Hippocampal astrocyte filling with Lucifer yellow and neurobiotin

Intracellular astrocyte filling with fluorescent dyes in fixed tissue

A mouse (two-month old BALB-c male) was perfused with Ringers, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M PBS (Bushong, et al., 2002). 100 micron-thick coronal slices were cut through the hippocampus using a vibratome. In CA1 stratum radiatum, one astrocyte was iontophoretically injected with 5% Lucifer yellow-CH in water and an adjacent astrocyte was injected with 2.5% Alexa Fluor 568 / 2% neurobiotin (Vector, SP-1120) in 200 mM KCl (Bushong, et al., 2002). The tissue slices were then post fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde / 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M PBS. Confocal volumes were taken of the filled astrocytes with a Leica SPE inverted confocal microscope and the slices were further fixed with 2.0% glutaraldehyde in 0.15M sodium cacodylate buffer for 10 min on ice, followed by washing several times with 0.15M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4.

Photooxidation of Lucifer-yellow filled astrocytes

Tissues were treated for 15 min in blocking buffer (50 mM glycine, 5 mM KCN, and 5 mM aminotriazole) to reduce nonspecific background reaction of diaminobenzidine derivatives, filtered Ce-DAB2 solution was added to a tissue slice at room temperature and incubated for 10 mins before photooxidation. A stream of pure oxygen was gently blown continuously over the solution. The Lucifer yellow was then excited using a standard FITC filter set (Ex 470/40, DM 510, Em BA520) with intense light from a 150W-xenon lamp. Illumination was stopped as soon as a light brown reaction product appeared within the filled astrocyte (8–10 min), as monitored by transmitted light.

Blocking of first Ln-DAB2 product

Following photooxidation each tissue slice was washed several times with cold 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and then blocked with freshly prepared 100 mM acetyl imidazole in 0.15 M sodium chloride (3 × 5 min).

HRP labeling and enzymatic reaction of photooxidized cells

The tissues were incubated with cryoprotectant, then freeze-thawed to permeabilize the tissues (Knott, et al., 2009). The tissues were washed several times with 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4, incubated with 1% BSA in the cacodylate buffer for 30 min followed by overnight incubation with Vectorstain Elite ABC staining kit (Vector, PK6100). After rinsing several times for one hour with cold 0.1M cacodylate buffer pH 7.4, 20 ml of Pr-DAB2 solution and 5 μl 30% H2O2 were added to each tissue. After the neurobiotin-filled astrocyte turned brown, the tissue was washed several times with 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4.

Tissue processing for TEM

Tissues were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer for 20 min, washed several times with cacodylate buffer, post-fixed with 0.5% of OsO4 in cacodylate buffer for 30 min, dehydrated in an ethanol series of 0%, 20%, 50%, 70%, 90% and 100% on ice for 5 min each, 100% ethanol twice for five mins each at room temperature, 1:1 100% dry ethanol : dry acetone for five min, 100% dry acetone for five min, 50:50 dry acetone: Durcupan ACM for 30 min, four changes of Durcupan for one hour each, and embedded in a 60 °C oven for 48 hours.

Section preparation from cells and tissue

100nm thick sections were cut by an Ultra 45° Diatome diamond knife using a Leica Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome and sections were picked up on a 50 mesh copper grid (Ted Pella, G50). Sections were carbon coated on both sides by a Cressington 208 carbon coater to prevent charging of the plastic which can cause drift and thermal damage.

Electron microscopy

EFTEM was performed with a JEOL JEM-3200EF transmission electron microscope operating at either 200 or 300 KV, equipped with an in-column Omega filter and a LaB6 electron source. The samples were pre-irradiated at a low magnification of 100x for about 30 min to stabilize the sample and minimize contamination (Egerton, et al., 2004). The elemental maps were obtained at the M4,5 core-loss edge, the onset of which occurs at 832, 883 and 931 for lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce) and praseodymium, (Pr) respectively (Ahn and Krivanek, 1983). The EFTEM images of the pre and post-edges were obtained using a slit of 30 eV width. The electron energy-loss spectrum was acquired using the Ultrascan 4000 CCD detector from Gatan (Pleasanton, CA, USA). The conventional images and elemental maps were acquired using both the Ultrascan 4000 detector and the direct detection device (DDD) DE-12 from Direct Electron LP. (San Diego, CA). See supplemental experimental procedures for details.

Two-color elemental map merge and overlay on TEM

Elemental maps and TEM were pre-aligned in Photoshop (Adobe) and merged pixel-by-pixel using the following custom algorithm running in C++.

Where PixelTEM is the 24-bit RGB coordinate for the gray scale TEM image, and PixelOVR is the 24-bit RGB coordinate for the overlay hue at maximum saturation and brightness. T is a “transparency factor” whose value determines what percentage of the overlay color coordinate contributes to the final display pixel. The color coordinate for PixelOVR is calculated in the HSL (Hue, Saturation and Lightness) color space. In the following example, the hue (H) for PixelOVR is determined using two EELS channels:

Where S is a scale factor and I is the intensity of the signal for each respective channel and H1 and H2 are the arbitrary hues selected for each channels (e.g., red and green).

The lightness (I) for PixelOVR is calculated as follows:

Finally, the RGB coordinate for PixelOVR is determined using an HSL to RGB color space conversion algorithm where S is set to maximum. The transparency factor is calculated as follows:

The raw EELS data needs to be scaled between 0 and 255 (8-bits) and should be done prior to implementing the algorithm.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Multicolor EM paints multiple cellular markers by locally depositing specific Ln3+

Each Ln3+ visualized by electron energy-loss spectroscopy and energy-filtered EM

Elemental maps overlaid on conventional EM give multicolor EM

Applicable to immuno, genetically-encoded, and molecular probes in cells and tissue

Acknowledgments

We thank David Mastronarde (University of Colorado Boulder) and Liang Jin (Direct Electron) for help with scripting in Serial EM, and DE-12 direct detection device respectively, and James Bouwer, Thomas Deerinck, Junru Hu for advice and technical assistance. This work was supported by UCSD Graduate Training Programs in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology (T32 GM007752)(SP) and in Neuroplasticity of Aging (T32 AG000216)(SP), NIH GM103412 (ME), the W.M. Keck Foundation (ME) and NIH GM086197 (RT).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

S.A., R.T., and M.E. conceived and designed the experiments, S.A., M.M., R.R., S.P., E.B., B.G., M.B., and P.S. performed all experiments and analyzed data, and S.A., M.M., R.R., and R.T. wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn CC, Krivanek OL. EELS Atlas (Gatan) 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Aronova MA, Leapman RD. Development of Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy in the Biological Sciences. MRS Bull. 2012;37:53–62. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2011.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzig E, Patterson GH, Sougrat R, Lindwasser OW, Olenych S, Bonifacino JS, Davidson MW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hess HF. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science. 2006;313:1642–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1127344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock R. The uptake of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides: putting the puzzle together. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:863–868. doi: 10.1021/bc500017t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushong EA, Martone ME, Ellisman MH. Maturation of astrocyte morphology and the establishment of astrocyte domains during postnatal hippocampal development. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushong EA, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J Neurosci. 2002;22:183–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butko MT, Yang J, Geng Y, Kim HJ, Jeon NL, Shu X, Mackey MR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY, Lin MZ. Fluorescent and photo-oxidizing TimeSTAMP tags track protein fates in light and electron microscopy. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1742–1751. doi: 10.1038/nn.3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copolovici DM, Langel K, Eriste E, Langel Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides: design, synthesis, and applications. ACS Nano. 2014;8:1972–1994. doi: 10.1021/nn4057269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deerinck TJ, Martone ME, Levram V, Green DPL, Tsien RY, Spector DL, Huang S, Ellisman MH. Fluorescence photooxidation with Eosin - A method of high-resolution immunolocalization and in-situ hybridization detection for light and electron-microscopy. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;126:901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durner J, Klessig DF. Inhibition of ascorbate peroxidase by salicylic acid and 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, two inducers of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11312–11316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerton RF. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy. Plenum Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Egerton RF, Li P, Malac M. Radiation damage in the TEM and SEM. Micron. 2004;35:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez JM, Bilgin MD, Grossweiner LI. Singlet oxygen generation by photodynamic agents. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 1997;37:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gaietta G, Deerinck TJ, Adams SR, Bouwer J, Tour O, Laird DW, Sosinsky GE, Tsien RY, Ellisman MH. Multicolor and electron microscopic imaging of connexin trafficking. Science. 2002;296:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1068793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geze C, Mouro C, Hindre F, LePlouzennec M, Moinet C, Rolland R, Alderighi L, Vacca A, Simonneaux G. Synthesis, characterization and relaxivity of functionalized aromatic amide DTPA-lanthanide complexes. Bulletin De La Societe Chimique De France. 1996;133:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Halassa MM, Fellin T, Takano H, Dong JH, Haydon PG. Synaptic islands defined by the territory of a single astrocyte. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6473–6477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1419-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG. GLIA: listening and talking to the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:185–193. doi: 10.1038/35058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1009–1031. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell SW. Far-field optical nanoscopy. Science. 2007;316:1153–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.1137395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández AI, Oxberry WC, Crary JF, Mirra SS, Sacktor TC. Cellular and subcellular localization of PKMζ. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369:20130140. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Bates M, Zhuang X. Super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:993–1016. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061906.092014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullian C, Brunet JE, Thomas V, Jameson DM. Time-resolved fluorescence studies on protoporphyrin IX-apohorseradish peroxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;997:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(89)90188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan IM, Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Cationic TAT peptide transduction domain enters cells by macropinocytosis. J Control Release. 2005;102:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott GW, Holtmaat A, Trachtenberg JT, Svoboda K, Welker E. A protocol for preparing GFP-labeled neurons previously imaged in vivo and in slice preparations for light and electron microscopic analysis. Nat Protocols. 2009;4:1145–1156. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers J, van Ham TJ, Kalicharan RD, Veenstra-Algra A, Sjollema KA, Dijk F, Schnell U, Giepmans BN. FLIPPER, a combinatorial probe for correlated live imaging and electron microscopy, allows identification and quantitative analysis of various cells and organelles. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SS, Martell JD, Kamer KJ, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Mootha VK, Ting AY. Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nat Methods. 2015;12:51–54. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranto AR. Neuronal mapping: a photooxidation reaction makes Lucifer yellow useful for electron microscopy. Science. 1982;217:953–955. doi: 10.1126/science.7112109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell JD, Deerinck TJ, Sancak Y, Poulos TL, Mootha VK, Sosinsky GE, Ellisman MH, Ting AY. Engineered ascorbate peroxidase as a genetically encoded reporter for electron microscopy. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsunaga M, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Rosenblum LT, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules. Nat Med. 2011;17:1685–1691. doi: 10.1038/nm.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natera J, Massad W, Amat-Guerri F, Garcia N. Elementary processes in the eosin-sensitized photooxidation of 3,3 ′-diaminobenzidine for correlative fluorescence and electron microscopy. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology a-Chemistry. 2011;220:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Oakenfull D, Jencks W. Reactions of Acetylimidazole and Acetylimidazolium Ion with Nucleophilic Reagents - Structure-Reactivity Relationships. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1971;93:178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano RE, Martin OC, Kang HC, Haugland RP. A novel fluorescent ceramide analogue for studying membrane traffic in animal cells: accumulation at the Golgi apparatus results in altered spectral properties of the sphingolipid precursor. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1267–1279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano RE, Sepanski MA, Martin OC. Molecular trapping of a fluorescent ceramide analogue at the Golgi apparatus of fixed cells: interaction with endogenous lipids provides a trans-Golgi marker for both light and electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2067–2079. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palida SF, Butko MT, Ngo JT, Mackey MR, Gross LA, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. PKMζ, but not PKCζ, is rapidly synthesized and degraded at the neuronal synapse. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7736–7749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0004-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Draney D, Volcheck W, Bashford G, Lamb D, Grone D, Zhang Y, Johnson C, Achilefu S, Bornhop D, et al. Phthalocyanine dye as an extremely photostable and highly fluorescent near-infrared labeling reagent - art. no. 60970E. Optical Molecular Probes for Biomedical Applications. 2006;6097:E970–E970. [Google Scholar]

- Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, Chernomordik LV, Lebleu B. Cell-penetrating peptides. A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:585–590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell. 2005;122:735–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell U, Cirulli V, Giepmans BN. EpCAM: structure and function in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:1989–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell U, Dijk F, Sjollema KA, Giepmans BN. Immunolabeling artifacts and the need for live-cell imaging. Nat Methods. 2012;9:152–158. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao CY, Sondhi R, van de Nes PS, Sacktor TC. PKMζis necessary and sufficient for synaptic clustering of PSD-95. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1501–1507. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu XK, Lev-Ram V, Deerinck TJ, Qi YC, Ramko EB, Davidson MW, Jin YS, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. A Genetically Encoded Tag for Correlated Light and Electron Microscopy of Intact Cells, Tissues, and Organisms. Plos Biology. 2011;9:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa PA, Yucel JK, Veit B, Faulkner DJ, Deerinck T, Soto G, Ellisman M, Malhotra V. Complete vesiculation of Golgi membranes and inhibition of protein transport by a novel sea sponge metabolite, ilimaquinone. Cell. 1993;73:1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.