Abstract

Introduction

We describe Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Biomarker Core progress including: the Biobank; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta (Aβ1–42), t-tau, and p-tau181 analytical performance, definition of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) profile for plaque, and tangle burden detection and increased risk for progression to AD; AD disease heterogeneity; progress in standardization; and new studies using ADNI biofluids.

Methods

Review publications authored or coauthored by ADNI Biomarker core faculty and selected non-ADNI studies to deepen the understanding and interpretation of CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181 data.

Results

CSFAD biomarker measurements with the qualified AlzBio3 immunoassay detects neuropathologic AD hallmarks in preclinical and prodromal disease stages, based on CSF studies in non-ADNI living subjects followed by the autopsy confirmation of AD. Collaboration across ADNI cores generated the temporal ordering model of AD biomarkers varying across individuals because of genetic/environmental factors that increase/decrease resilience to AD pathologies.

Discussion

Further studies will refine this model and enable the use of biomarkers studied in ADNI clinically and in disease-modifying therapeutic trials.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Mild cognitive impairment, Cerebrospinal fluid, Plasma, Biomarkers, Immunoassay, ADNI, Disease-modifying therapy, Aβ1–42, Tau

1. Introduction

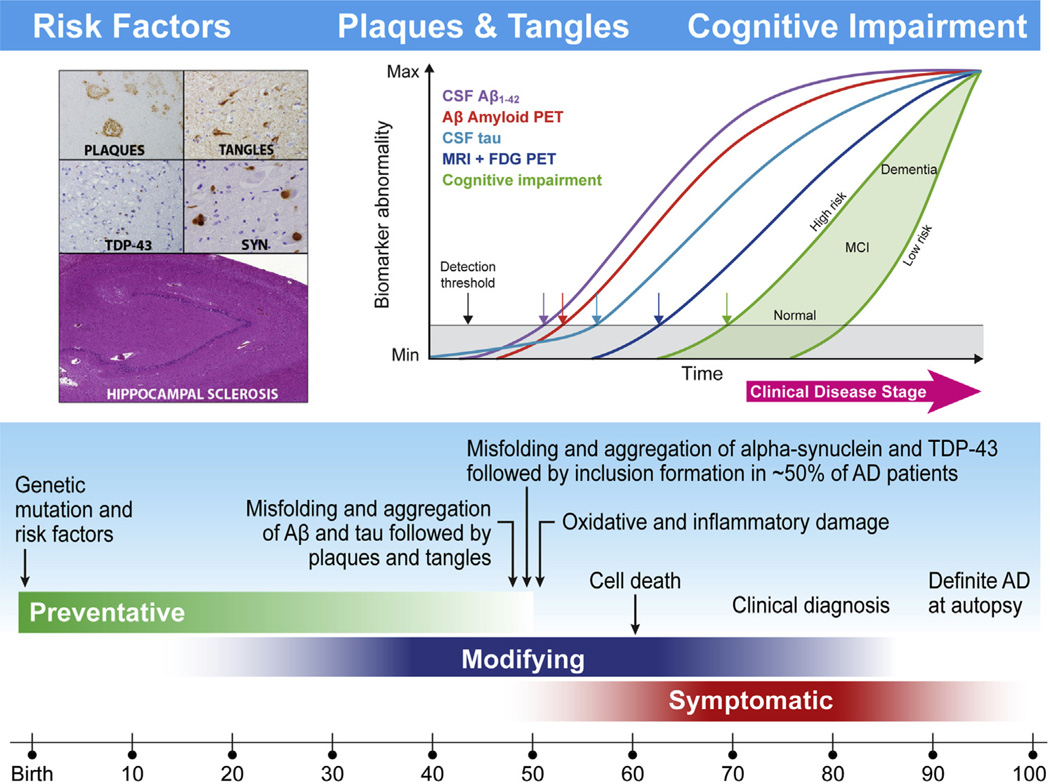

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia [1,2]. It is a complex progressive neurodegenerative disease that leads to the loss of memory and cognitive function. The disease is pathologically characterized by amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) that are composed largely of fibrillar forms of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau), respectively. During the past two decades cumulative molecular and clinical studies have provided evidence for our understanding of the molecular characteristics and progressive pathologic features of AD. These pathologic changes are reflected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), respectively, by lowered levels of Aβ1–42 followed by increased total tau (t-tau) or p-tau181. In the Biomarker Core of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI-1) located at the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn), we defined cut points for the use of these biomarkers and their ratios using an ADNI-independent autopsy-based Penn AD cohort and age-matched living normal control (NC) subjects. Cognitive decline in AD patients closely correlates to neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), synapse loss, and neurodegeneration [3–5]. However, there is a growing awareness for the occurrence of one or more copathologies in sporadic AD including Lewy bodies (LBs), vascular disease, transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) inclusions, and hippocampal sclerosis which most likely contributes to the variable timeline for the progression of AD [6] as reflected in the imaging, CSF biomarkers, and clinical features of patients with dementia of the AD type (DAT) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

This figure is a newly adapted schematic depicted in two previous Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) reviews [47,124] that updates the current understanding of the hypothetical time line for the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neurodegeneration and cognitive impairments progressing from normal controls (NC) to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and then to AD. Age is indicated at the bottom, whereas the green, blue, and red bars indicate the time at which preventive, disease-modifying, and symptomatic interventions, respectively, are likely to be most effective. Within the aqua bar are shown milestones in the pathobiology of AD that culminate in death and autopsy confirmation of AD. The proposed ADNI model of the temporal ordering of biomarkers of AD pathology relative to stages in the clinical onset and progression of AD is shown in the insert at the upper right based on Jack et al. [58], whereas the insert at the left illustrates the defining plaque and tangle pathologies of AD and common comorbid pathologies including Lewy body pathology (LBP), transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), and hippocampal sclerosis. In the insert on the right, clinical disease is on the horizontal axis and it is divided into three stages; cognitively normal, MCI, and dementia. The vertical axis indicates the range from normal to abnormal for each of the biomarkers and for measures of memory and functional impairments. The plot in the upper right of this figure is taken from reference #58 with permission.

AD can be divided into different phases: (1) a preclinical phase in which subjects are cognitively normal but have mild AD pathology, (2) a prodromal phase known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and (3) a phase when patients show dementia with impairments in multiple domains and loss of function in activities of daily living [4,7–9]. On the basis of the prevailing scientific evidence, CSF Aβ1–42 and the tau proteins have been incorporated into the revised research diagnostic criteria for AD together with β-amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [10–13], and tau amyloid PET imaging is now also available [14,15]. It is being added to the ADNI portfolio of imaging technologies. ADNI-1 studies reported evidence of AD pathology in one-third of the cognitively intact elderly NC subjects solely based on CSF Aβ1–42 [16,17]. It is time to consider developing strategies to identify AD at the presymptomatic and prodromal phases to optimize the potential efficacy of disease-modifying therapies, and to enable drug development aimed at AD prevention. A key goal of ADNI continues to be the improvement of the standardization of biomarker measurements to enable their use in clinical AD trials, across multiple testing laboratories, and in routine clinical practice. Thus, the standardization of both preanalytical (at the level of biofluid sample collection, handling, aliquot preparation, and storage) and analytical sources of variability continues to be a priority of the Penn Biomarker Core and we continue to collaborate with biomarker scientists on these issues. We participated in recent consensus group and we are part of the Alzheimer’s Biomarker Standardization Initiative, providing a set of recommendations for 10 preanalytical factors [18]. We have continued the work of analytical method standardization in the Penn Biomarker Core of ADNI and also have collaborated with colleagues in the Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC) in support of Aβ1–42 calibrator standardization, based on mass spectrometry, across various immunoassay platforms [19]. We expect that an outcome of all these efforts will be the availability of the most highly standardized methods for CSF Aβ1–42 and tau proteins. In this review, we summarize progress by the Penn Biomarker Core of ADNI using the developed pathological CSF biomarker profile that sensitively detects Aβ amyloid plaque burden (below the threshold for the CSF Aβ1–42 concentration) and NFTs, synapse loss, and neurodegeneration (above-threshold for CSF tau protein concentrations) [16]. We continue the collaborative work to develop biomarker tests for α-synuclein (α-syn) to indicate the presence of concomitant LBs and forTDP-43 as an indicator of inclusions of this biomarker in early AD, early and late MCI, and NC subjects. The Penn Biomarker Core has collaborated with other ADNI Cores in multimodal data analyses across ADNI to temporally order changes in clinical measures, imaging data, and chemical biomarkers that refine and expand our understanding and interpretation of the pathophysiology involved in the disease progression from NC to MCI and from MCI to AD. The hypothetical model of the temporal evolution of changes in the AD biomarkers will be further developed within the Biomarker Core studies in the ADNI-2 grant (Fig. 1) and informs our plans for the ADNI-3 competing renewal application.

2. Biofluid repository update

2.1. Overview

From 2010 through 2015, the ADNI-1 and II biofluid repository at Penn continuously receives biofluids (CSF, plasma, and serum) shipped from all ADNI sites followed by aliquoting and monitoring after storage in −80°C freezers. This effort requires 24/7 attention by the Penn Biomarker Core team. Since its inception in 2004, no lost samples or other untoward misadventures were recorded. The biofluid samples are collected and shipped in accordance with ADNI biomarker standard operating procedures (SOPs) established in ADNI-1 after consultation with members of the Private Partners Scientific Board (PPSB) and other ADNI advisory biomarker scientists. We continue to work closely with the ADNI Clinical Core on recording essential details for each collected sample from the jointly developed biofluid tracking form. These SOPs are essential to ensure the integrity of samples, accurate identification of the samples received and aliquots prepared from them, and sample stability. Continuous vigilance of the characteristics of each received sample by Biomarker Core staff and regular communication with Clinical Core staff and individual sites regarding any issues that may arise involving mislabeled samples or other issues has enabled the correction of the issues related to this function of the Biomarker Core, and the regular communication between this Core and the ADNI sites facilitates the collection of accurate data for every collected sample.

2.2. Current status of the ADNI biofluid bank

2.2.1. ADNI-1, 2, and Grand Opportunity

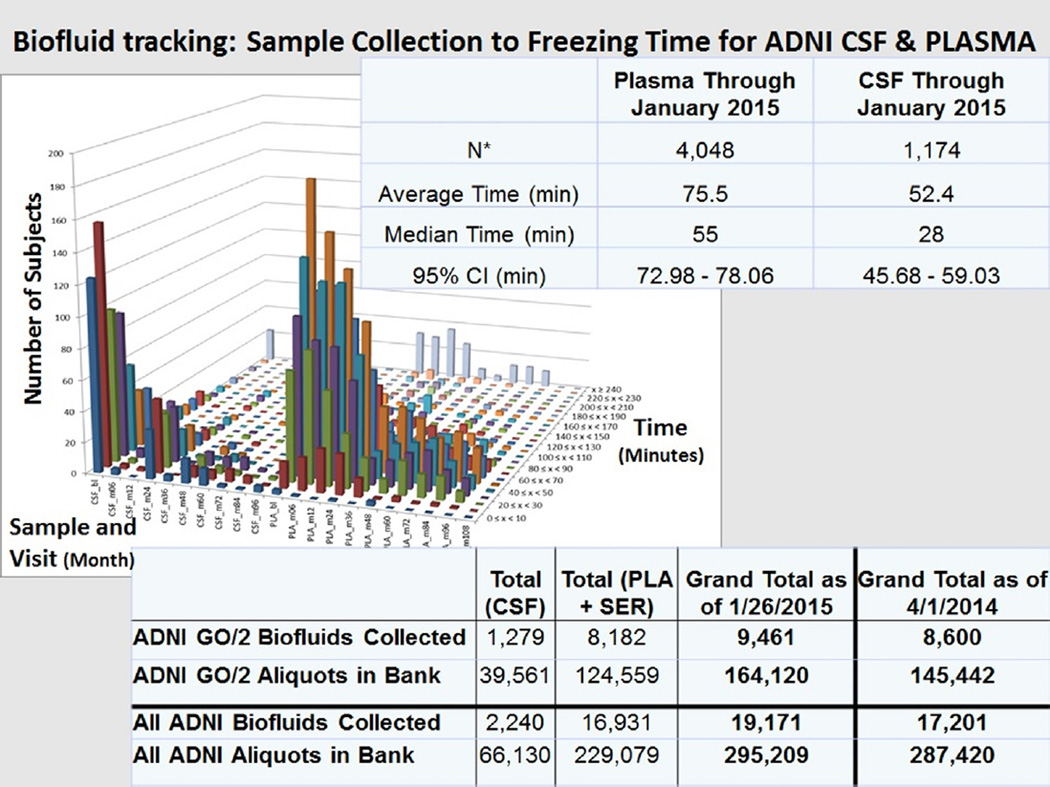

From April 21, 2010 and from March 7, 2011, the dates that the first ADNI-Grand Opportunity (GO) and first ADNI-2 biofluid samples were received, respectively, through January 26, 2015, a total of 9461 biofluids were received, processed, and 164,120 aliquots prepared (1279 CSF, 8182 plasma, and serum samples; 39,561 CSF aliquots, 124,559 plasma and serum aliquots), bar code labeled, and stored in dedicated ADNI freezers at −80°C (Fig. 2). The totals for ADNI-1, ADNI-2, and ADNI-GO are summarized in Fig. 2. Temperature monitoring of each freezer is done everyday, 365 days a year, with a telephone alarm system, and one Penn Biomarker Core staff person is always “oncall” to respond to an alarm. For each primary biofluid sample collected, the following information is maintained in the ADNI Biomarker Core database at Penn: biofluid type (CSF, plasma, serum, urine [only ADNI-1]), coded subject and visit ID, six digit license plate number, visit date and time, date and time of receipt, condition of samples as received, biofluid sample volume and number of aliquots, and the details of sample preparation such as time from collection to time of transfer, and to time of freezing are recorded for each sample from each study site. The database is backed up daily on each of two external “brick” hard drives. The latter are stored outside the Biomarker Core laboratory in a secure location in a different building to ensure data security in the event of a catastrophic failure of the server in which the database resides.

Fig. 2.

Summary of (1) biofluid tracking: time from sample collection to freezing for Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma samples and (2) ADNI GO/2 number of biofluids collected and number of aliquots in the Penn ADNI Biobank and the total of ADNI 1/2/GO biofluids collected and banked as of January 26, 2015. This collection time data for each ADNI biofluid sample is tracked in the Penn ADNI Biofluid Biobank database.

2.2.2. Rationale for sample preparation preanalytical steps

The preanalytical steps involved in sample preparation and the analytical method itself are two well-known sources of variability in CSF biomarker measurements. An important basis for the preparation procedure for samples at each ADNI site was the principle of keeping the number of steps involved to the minimum and keeping the time at room temperature before freezing samples on dry ice to the minimum practically possible. For example, CSF samples are collected in labeled polypropylene collection tubes followed by transfer to labeled polypropylene transfer tubes (n = 2), with no centrifugation step, then are placed on dry ice immediately, and shipped on dry ice to the Penn ADNI Biomarker Core laboratory where they subsequently are thawed at room temperature. Within 30 minutes of thawing the CSFs are aliquoted into 0.5-mL polypropylene tubes and placed in storage boxes in designated locations in −80°C freezers. This streamlined process does include one additional thaw–freeze step compared with protocols that prepare and label individual aliquots at local sites but reduces risk for variable sample preparation and contributes to consistency of sample handling in our experience. The data on sample preparation times for ADNI biofluids are summarized in Fig. 2 showing average times of 52.4 and 75.5 minutes from sample collection to freezing the samples for CSF and plasma, respectively. The fastidiousness with which staff at the ADNI sites prepare and ship biofluid samples is noteworthy. The use of centrifugation of CSF before freezing has been a debated topic but investigators have shown for Aβ1–42 and tau proteins no difference in results comparing centrifuged versus not centrifuged samples [18]. A just published systematic study of preanalytical factors confirmed the lack of effect of not-centrifuging versus centrifugation of CSF samples and also the stability of Aβ1–42 and tau protein concentrations out to three freeze–thaw cycles but with decreases after four cycles for Aβ1–42 and t-tau but not p-tau181 [127]. The use of a second thaw–freeze cycle in the ADNI study for CSF samples is within the observed stability in this and other studies (data on file in the ADNI Biomarker Core laboratory).

2.2.3. Shipments of biofluid aliquots to investigators for studies approved by the ADNI National Institute on Aging(NIA) Resource Allocation Review Committee

An integral part of the responsibilities of the Penn Biomarker Core is to respond to requests for biofluids that are approved by the Resource Allocation Review Committee (RARC). The 18 RARC-approved requests for ADNI biofluids are summarized in the latest edition of the annual Biofluids reports that are available on the Laboratory of Neuroimaing (LONI) ADNI website (https://ida.loni.usc.edu/pages/access/studyData.jsp?categoryId=11&subCategoryId=58).

Results from the most recent downloaded and published studies are discussed in later sections of this review.

3. Qualification of the analytical performance of CSF biomarker immunoassays

With the development of Aβ1–42, total tau (t-tau), and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (p-tau181)-specific monoclonal antibodies, efforts to develop singleplex and multiplex platforms to measure the AD biomarkers in human CSF have emerged. Based on reported studies, the precision performance of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and multiplex Luminex-xMAP platforms, two of the most widely used platforms for the measurement of CSF biomarkers, supports their intended use to detect AD Aβ plaque and NFT pathology by measuring CSF Aβ1–42 and tau [20]. ADNI adopted the Luminex xMAP platform and the multiplex INNO-BIA Alz-Bio3 immunoassay to measure the CSF AD biomarkers based on reported within-center precision performance and equivalent clinical utility to that of the INNOTEST ELISA immunoassay [21]. Precision performance was most recently documented for 133 runs, using four different kit lots, and completed over the time frame from August 2013 through January 2015. The study included a formally outlined, prospective quality control strategy [20]. Using an AD-like abnormal CSF and a normal CSF pool, the percent coefficient of variation (%CV) values obtained were 9.2% and 10.2%, 7.4% and 10.1%, 11.2% and 12.2%, for respectively, Aβ1–42, t-tau, and ptau181 using the Luminex-xMAP platform in the Penn ADNI Biomarker Core laboratory [22], which confirmed previously published within-center data [23].

Of note, the concentrations of each biomarker measured by xMAP in the same CSF samples differ from those measured by ELISA, although the concentrations are highly correlated [24–26]. Several studies including a study led by the ADNI Biomarker Core assessed the interlaboratory variability of the CSF AD biomarkers described previously. Briefly, these studies showed that following a well-vetted protocol the substantial intercenter variability of both immunoassay platforms [23,27,28] can be improved on. The studies suggested that several factors can account for interlaboratory variability for CSF AD biomarker measurements. Besides preanalytical factors, for instance, any analytical step not included in the manufacturer’s formal protocol (e.g., repeated pipetting of reagents or samples, transfer of samples to an intermediary 96-well plate, differences in data processing, selection of calibration curves, criteria used for acceptance of individual runs based on internal quality control samples) that might be used by analysts can be a significant source of unexpected variability.

Our recent application of a unified detailed test procedure for the Luminex INNO_BIA AlzBio3 platform across three independent laboratories showed acceptable interlaboratory variation. In this pilot study, we observed a strong correlation of concentrations for each analyte between the participating centers (R2 > 0.95; linear regression: center versus overall center mean) and average total interlaboratory variability for 10 pools of CSF (variability components “run” and “lab”) over eight runs were 16.5% for t-tau, 10.9% for Aβ1–42, and 9.2% for p-tau181. Therefore, we are convinced that the implementation of a unified SOP, careful documentation of critical parameters of the test procedure, and the rigorous adherence to detailed test instructions can result in improved CSF analyte concentration reproducibility across laboratories [29]. In addition, the experience of trained personnel who are very familiar with this complex procedure is essential to decrease variability. Further improvements in immunoassay performance within and between centers can be anticipated as manufacturers develop fully automated platforms that will reduce substantially the number of manual steps and minimize matrix interferences. A proof-of-principle study reported by Figurski et al showed that combining the standard bead-based xMAP plasma Aβ1–42 immunoassay with a robotic pipetting technique achieved a 50% improvement in precision performance compared with other published studies [30].

4. Progress in clinical utility of CSF AD biomarkers

4.1. CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181 measurements

CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181 have been extensively studied for the early detection of AD before and after the start of ADNI in 2004 [31–35]. For the ADNI Biomarker Core, the publication by Shaw et al. [16] was a major milestone (Table 1). It reported cut points using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis for the discrimination of AD patients from NC subjects based on an ADNI-independent autopsy-confirmed cohort. The defined cut points were successfully applied to the ADNI-1 cohort and these values have been used in many other clinical studies [36] and clinical trials. DeMeyer and collaborators independently confirmed the clinical utility of these cut points using a mixture-modeling approach in the ADNI-1 study subjects and in an ADNI-independent Belgian autopsy-based study cohort [17]. Toledo and coworkers provided additional validation data using more than 1000 ADNI subjects (ADNI 1, GO, 2), including follow-up samples. Mixture modeling approaches applied to CSF in combination with PETAβ amyloid imaging data led to converging cut point values similar to the previously established levels [37] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of main findings in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker studies.*

| Number of subjects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. | Control † | MCI | AD | Other‡ | Main findings |

| [16] | 114 52§ |

196 | 100 56§ |

– | CSF biomarker signature defined by Aβ42 and t-tau in autopsy-confirmed AD cohort confirmed diagnostic utility in the ADNI cohort, and this signature appears to predict progression from MCI to AD. |

| [17] | 114 | 200 57§ |

102 65§ |

8§ | Autopsy-confirmed AD cases were correctly classified with the AD CSF feature derived from the ADNI cohort by mixture modeling, and the model showed excellent sensitivity to predict MCI to AD progression in an ADNI- independent cohort. |

| [24]§ | 89 | 14 | The INNOTEST ELISA and INNO-BIA AlzBIo3 immunoassays yielded different absolute values for CSF Aβ42, t-tau, and p-tau, but they performed equally well in identifying AD amyloid plaque pathology (PiB-PET). |

||

| [32]§ | 184 | – | 150 | 79 | Combined measure of CSF Aβ42 and tau improved diagnostic utility to discriminate AD from control and other neurodegenerative diseases. |

| [34]§ | 39 | 187 | – | – | Concentration of CSF tau, p-tau181, and Aβ42 were associated with future development of AD from MCI. |

| [37] | 259 | 415 | 146 | – | Provides evidence for detection of different aspects of AD Aβ pathology by CSF Aβ1–42 compared with amyloid PET (Florbetapir) |

| [39]§ | 90 | – | 49 | – | CSF Aβ42 level corresponded with the findings of brain amyloid imaging (PiB-PET), and CSF t-tau/Aβ42 ratio predicted future dementia in cognitively normal elderly. |

| [40]§ | 304 | 750 | 529 | – | Combination of CSF Aβ42/p-tau and CSF t-tau identified incipient AD. |

| [41]§ | – | 137 | – | – | CSF Aβ42 levels are fully decreased at least 5–10 years before conversion to AD. CSF t-tau and p-tau increased later than Aβ42. |

| [42]§ | 251 | 236 | 631 | 267 | T-tau/Aβ42 ratio of >0.52 constitutes a robust CSF AD profile, and was validated in the validation cohort (N = 1442). |

| [43] | 103 | 249 | 22 | – | CSF Aβ42 and amyloid PET(Florbetapir) were consistent, however CSF Aβ42 did not become abnormal before fibrillary Ab accumulation. |

| [44]§ | 161 | Concordance between CSF Aβ42- and Florebetapir PET- based classification for amyloid status was 93% in AD subjects from EXPEDITION 1&2, using Lilly/PPD ELISA or AlzBio3. Cut point estimates to prospectively discriminate amyloid negative subjects for EXPEDITION 3 was set at 249 pg/mL. |

|||

| [50]§ | 337 | – | 547 | 30 | MRI findings of vascular event was associated with lower CSFAβ42 in AD and VD, and associated with higher CSF tau in SMC. |

| [51] | 110 | 187 | 92 | – | CSF α-syn level improved the diagnostic utility of CSFAβ42, t-tau and p-tau. |

| [53] | 50 | 74 | 18 | – | Established trajectories for CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181 out to 3–4 years; supported the hypothesis that Aβ1–42 changes precede tau protein changes and both occur before DAT. “Stable” and “decliner” Aβ1–42 trajectories in MCI and NC with normal BASELINE Aβ1–42 were identified. |

| [56] | 96bl, 96m12 | 155bl, 155m12 | 74bl, 74m12 | – | ADNI results strongly supported the hypothesis that changes in CSF and imaging biomarkers occurs in advance of the clinical diagnosis of AD. |

| [57] | 229 | 397 | 193 | – | Longitudinal analysis of ADNI CSF data during up to 36 months supported a hypothetical sequence of AD pathology, suggesting that biomarker prediction for cognitive change is stage dependent. |

| [60]§ | – | 110 | – | – | The injury biomarkers CSF t-tau and p-tau and hippocampal atrophy can predict further cognitive decline in MCI with Aβ pathology. |

| [69] | 106 | 183 | 92 | – | Significant correlation between CSF BACE 1 activity and sAPPβ, but no diagnostic utility for these biomarkers in ADNI were found. |

| [125]§ | A: 251 B: 105 |

A: 287 MCI-AD + 399 sMCI C: 118 MCI |

309 | 99 | CSF Aβ42 levels were associated with AD diagnosis and cortical Aβ accumulation independent of APOE genotype, which was validated in other independent cohorts. |

| [126] | 92 | 149 | 69 | – | apoe ε4 levels in CSF, but not in plasma were associated with clinical changes. |

Abbreviations: MCI, mild cognitive impairment; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

The studies included in this table meet selection criteria for: subject number (>100 per group), included AD subjects, or MCI subjects who progressed to AD, novelty, and/or clinical significance.

Number of subjects in “Control” included healthy controls, neurologic disease controls without dementia, or disease controls without neurologic diseases.

“Others” indicates subjects with dementia who were not classified as Alzheimer’s type, including vascular dementia, frontotemporal degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson’s disease (PD) dementia, multiple system atrophy (MSA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

Indicates non-Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort.

Two independent analyses of the ADNI-1 data set provided evidence that the CSF Alzheimer profile characterized by decreased Aβ1–42 or an elevated tau/Aβ1–42 ratio clearly identifies subjects positive for Aβ plaque and tangle burden who are therefore at risk for progression to AD [16,17], and this finding is consistent with that reported in many other studies [34,38–42]. These CSF biomarker data support their use for the early detection of AD despite the fact that different analytical platforms were used and that the patient populations were heterogeneous, and they also provide support for the revised research diagnostic criteria for AD dementia [11], MCI due to AD [10,12], and the definition of preclinical stages of AD [13]. However, differences in the concentration values for the AD CSF biomarkers across numerous studies that used different analytical platforms (i.e., ELISA, Luminex-xMAP, and Mesoscale Discovery platforms) have been observed. Therefore, reduction and control of analytical variability across laboratories is an important goal in this field, and efforts to minimize the analytical variability are underway (reviewed in [20] and see later for a more detailed discussion). The observed low agreement between the different proposed imaging and CSF neurodegeneration biomarkers indicates that each of these technologies has a different sensitivity and specificity to detect the earliest preclinical changes or to differentiate AD-related pathology from other neurodegenerative diseases [46].

The main findings from studies of the ADNI cohort since its inception in 2004 were recently updated, well-summarized, and discussed for their considerable clinical implications by Weiner and collaborators [47].

4.2. The heterogeneous pathologic features of AD

The brains of patients who have late-onset AD verified by neuropathologic diagnosis at autopsy have widespread distribution of amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that are the pathologic hallmarks of this disease. In addition, a significant number of AD patients at autopsy have one of more concomitant pathologic findings (comorbidities) including LBs, vascular disease, TDP-43, hippocampal sclerosis, and argyrophilic grain disease. In the review of the first series of 22 brain autopsy cases of ADNI subjects that included 20 subjects with a clinical diagnosis of AD and 2 with MCI, all had evidence of plaque and tangle pathology. Importantly, only four had pure AD pathology with the remainder having coincident pathologic diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), TDP-43 proteinopathy, argyrophilic grain disease, and hippocampal sclerosis [46]. This series is small in number and the future reporting of the neuropathologic findings in ADNI patients will help to substantiate these findings and enable correlation studies with CSF biomarkers. In a study of the association of AD CSF biomarkers in patients with autopsy-confirmed coincident neuropathology that included 142 Penn Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center (ADCC) subjects with “pure” AD, and AD combined with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) pathology, including tau (FTLD-Tau) and TDP-43 (FTLD-TDP) inclusions or LBs [48], it was shown that CSF Aβ1–42 and t-tau levels outperformed clinical diagnosis to predict the presence of AD neuropathology. Vascular pathology is also frequently observed in demented subjects with AD pathology, and studies using ADNI subjects [49] and non-ADNI subjects [50] showed that vascular pathology measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be associated with regional neurodegeneration or with CSF AD profile.

4.2.1. Detection of LB pathology in AD patients

The heterogeneous neuropathologic features frequently observed in clinically diagnosed AD patients may be reflected by distinct changes in additional CSF biomarkers such as decreased α-syn levels that are characteristic of LB pathology. The combination of AD-associated biomarkers with other CSF protein signatures has the potential to improve the diagnostic or prognostic performance as compared with tau and Aβ alone based on a study in 389 ADNI and 102 subjects of the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative [51]. Wang and collaborators reported additional diagnostic utility for phosphorylated CSF α-syn levels [52]. A mismatch between CSF α-syn and p-tau181 (lower level of α-syn and higher p-tau181 level) was tested in ADNI subjects to account for expected lower α-syn due to PD pathology compared with an increase associated with AD pathology. The inclusion of this mismatch in AD classifiers may improve the clinical performance of these CSF biomarkers [51].

4.2.2. Variable rates of decline for CSF Aβ1–42 may reflect AD disease heterogeneity

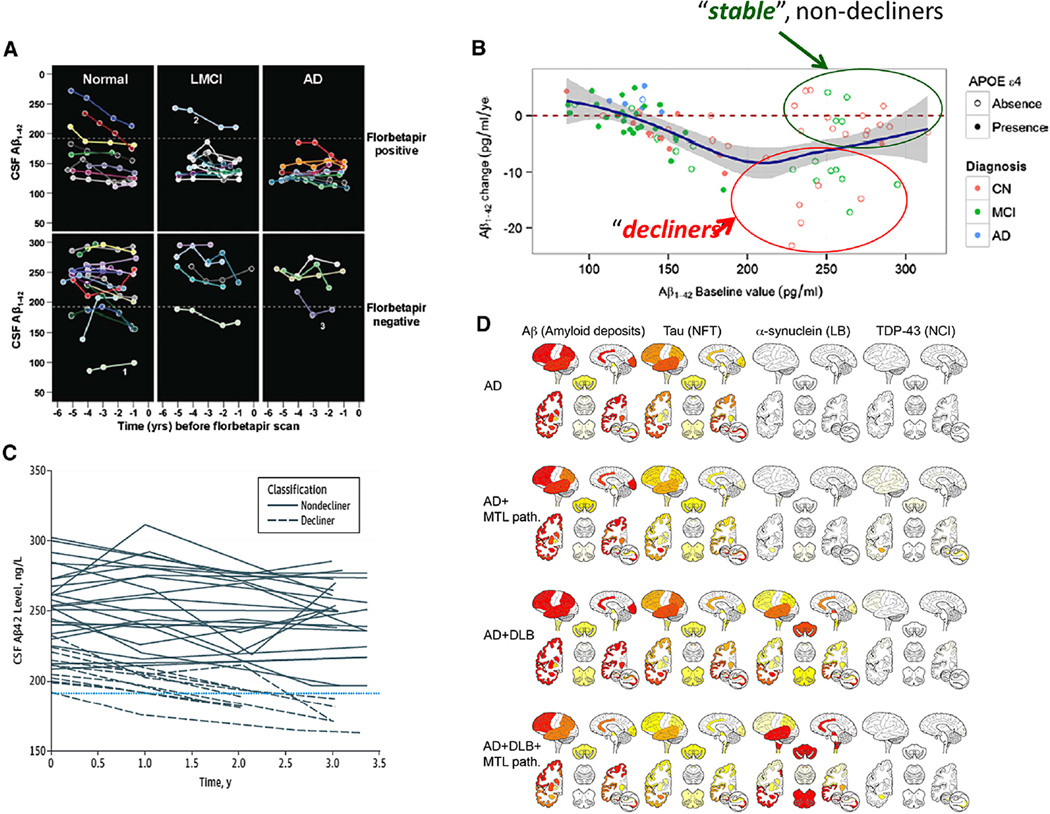

In addition to neuropathologic heterogeneity, the observation of longitudinal changes in CSF biomarker levels in the ADNI cohort revealed that there are distinct populations of subjects with normal baseline CSF Aβ1–42 values: those who remain stable and others who show a decline during follow-up (Fig. 3A–C) [43,45,53]. In the ADNI add-on study of the longitudinal trajectories of CSF biomarkers in 141 subjects with three or more CSFs collected longitudinally between 2005 and 2014, there were 35 whose baseline Aβ1–42 concentration values were above the 192 pg/mL cut point. The finding that 15 of these subjects (seven cognitively normal, eight MCI), followed longitudinally for 3–4 years from baseline, with normal baseline CSF Aβ1–42 had values declining toward the abnormal range at a mean annual change of −9.2 pg/mL is consistent with the hypothesis that these are individuals who have AD-like neuropathologic changes taking place in their brains at the time of their baseline visit as compared with the 20 subjects whose normal baseline values were stable at a mean annual change of −0.5 pg/mL [53]. Interestingly, the majority (all but two) of the stable and decliner subjects was APOE ε4 negative (see Fig. 3B) and these patient subgroups were not statistically different at BASELINE for mean cognitive and memory tests, had comparable hippocampal volume values, but their Aβ1–42 values differed, 257 versus 211 pg/mL (P < .001) [45], respectively. These preliminary data support the continued need for longitudinal lumbar punctures and CSF analyses in ADNI subjects to generate more statistically robust numbers of subjects with prolonged longitudinal biomarker profiles. ADNI is well positioned to provide larger numbers of subjects whose biomarker levels will move from normal values to pathological values as described in these ADNI studies [43,45,53] (Fig. 3A–C). Future studies are needed to assess what biomarker, imaging, and/or genetic factors predict which MCI and cognitively normal subjects with above cut point values for CSF Aβ1–42 are at risk to decline to pathologic values and significant Aβ plaque burden and progression to AD.

Fig. 3.

(A) Plot of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid beta (Aβ1–42) concentration (pg/mL) versus time (years) before florbetapir scan in the 27 normal, 17 mild cognitively impairment (MCI), and 16 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) subjects in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study. These are the subjects who participated in the ADNI longitudinal CSF biomarker study and who also had a florbetapir scan. Each colored line corresponds to an individual subject and each point on a line corresponds to a CSFAβ1–42 value from a single lumbar puncture (with permission from reference #43). The horizontal dotted line in each panel represents the CSFAβ1–42 cutoff value of 192 pg/mL. (B) Plot of the change (pg/mL/year) in CSFAβ1–42 concentration during 3–4 years follow-up time (Y axis) versus CSFAβ1–42 concentration at baseline in the 141 ADNI subjects who participated in the longitudinal CSF biomarker study (with permission from reference #53). The green circle includes the 20 study participants whose baseline Aβ1–42 value was normal (above 192 pg/mL) and whose Aβ1–42 value remained stable at an average yearly rate of −0.5 pg/mL/year for 3–4 years; the red circle includes the 15 participants whose baseline Aβ1–42 value was normal and whose Aβ1–42 value declined at an average yearly rate of −9.2 pg/mL/year over 3–4 years. (C) Plot of CSFAβ1–42 concentration (pg/mL) versus time for the 35 participants whose Aβ1–42 values were normal (above the 192 pg/mL cutoff) in the ADNI longitudinal study. The horizontal dashed line corresponds to the Aβ1–42 cutoff value (with permission from reference #45). (D) Heatmaps summarizing the semiquantitative neuropathological grading (from left to right: amyloid deposits, neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), Lewy bodies (LBs), and neuronal cytoplasmatic TDP-immunoreactive inclusions (NCI) for the different neuropathologic diagnostic groups (from top to bottom: AD, AD + medial temporal lobe (MTL) pathology, AD + dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), AD + DLB + MTL pathology, and DLB + MTL pathology) (with permission from reference #46).

4.3. Multimodal approach including CSF biomarkers

Disease progression and AD endophenotypes appear to be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Baseline and longitudinal data from ADNI were used to explore the association between biomarkers and clinical parameters at different stages of the disease. As suggested by Jack and colleagues [54] and tested by Caroli and Frisoni [55] and others [56,57], individual biomarkers vary in their rate of change across different stages of AD. Results from the ADNI cohort supported the model of temporal progression of biomarker abnormalities [54,58]: a reduction in CSF Aβ1–42 (or increased plaque burden measured by Aβ amyloid PET) in cognitively normal NC subjects occurs first, followed by t-tau elevation, hippocampal atrophy, and ultimately clinical deterioration.

Based on this model of the dynamics for AD biomarkers according to the disease stage of AD, Walhovd reported an optimum combination of imaging and CSF biomarkers to differentiate NC from AD subjects. They have found that imaging biomarkers, but not CSF biomarkers, were significantly associated with changes in cognitive scores in the MCI group [59]. In non-ADNI subjects with MCI and evidence of Aβ amyloid pathology, the abnormality in injury markers (high CSF t-tau and hippocampal atrophy) could help to identify those subjects with MCI due to AD who will more rapidly progress to dementia [60].

Genetic factors, such as the APOE ε4 allele, may influence this rate of change. In addition to the effect of genetic factors on neurodegeneration, several other factors (e.g., smoking, body mass index) may modulate the disease trajectory although these results have been the subject of contradictory reports [61,62]. Based on the small number of cases that came to autopsy in the ADNI study, we found that, even in a study that was focused on typical AD cases, most of the subjects had coincident or comorbid neurodegenerative disease pathologies such as LBs or TDP-43 inclusions that were not diagnosed before death (Fig. 3D) [46]. These findings underscore the complexity of different factors that can contribute to DAT. The existence of heterogeneous subgroups with different clinical characteristics might have different prognoses and would potentially need different treatment approaches. In summary, combined multimodal analyses including CSF biomarkers, genetic factors, and different imaging biomarkers and blood-based biomarkers continue to be a long-term aim for achievement of more accurate discrimination of AD from other neurodegenerative diseases and more accurate prediction of time course of disease progression in the individual patient [46].

The Biomarker Core will further determine in ADNI 3 which additional biomarkers could add to the predictive performance of CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181.

5. Candidate new biomarkers

5.1. β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 and soluble amyloid precursor proteins

β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1, β-secretase) is a membranous enzyme responsible to the production of Aβ species from amyloid precursor protein (APP). A sensitive and specific activity assay for BACE1 was previously developed [63,64]. The assay detected BACE1 enzyme activity in extracts of human brain tissues and, unexpectedly, in human CSF [65]. The expression level and activity of BACE1 in CSF was tested in ante-mortem CSF samples of NC, MCI, and AD patients. BACE1 levels and activity were significantly increased in CSF of the MCI group as compared with NC and AD subjects [66]. Addition of CSF BACE1 activity and concentrations of α- and β-cleaved soluble APP (sAPPα and sAPPβ, respectively) could not improve the separation of AD from NC as compared with the performance of the classical AD biomarkers (Aβ1–42 and tau) [67]. When AD patients were classified in terms of disease severity, only MCI showed higher BACE 1 activity as compared with AD or NC [66]. A recent study in the ADNI cohort found no significant differences in CSF BACE1 activity and sAPPβ concentrations between NC and stable MCI, progressive MCI, or AD patients, and no correlation with CSF Aβ1–42 or with plasma Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40, but found some correlation with CSF tau levels [68]. Another study in ADNI-1 cohort with a small number of subjects with 2 years follow-up replicated negative results for diagnostic performance. There was no effect of APOE ε4 positive genotype on BACE1 activity or sAPPβ concentration, but males showed higher sAPPβ concentration than females. The significant correlation of BACE1 activity and sAPPβ concentration with tau proteins, consistent with the previous study, suggested that their correlation may be linked with neuronal/synapse number in the brain [69]. Although these results do not support the diagnostic utility of BACE1 activity in CSF, the correlation of BACE1 activity with sAPPβ and axonal degeneration supports their role as biomarkers for pharmacodynamics monitoring of BACE1-targeted clinical trials. Confounding factors including demographics may influence the poor diagnostic utility of CSF BACE1 activity for AD. More studies related BACE1 activity or protein levels are required.

5.2. Novel biomarkers discovered by rules based medicine multiplex immunoassay

A RARC approved add-on study used a Luminex bead-based immunoassay technology developed by Rules Based Medicine (RBM, Austin, TX) to screen CSF and plasma samples obtained from the ADNI cohort. First, a pilot study was conducted with non-ADNI Penn CSF samples to interrogate levels of 151 analytes with the Human Discovery Multi-Analyte Profile™ (MAP) panel. The panel was enriched in cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, and AD biomarkers in non-ADNI Penn CSF samples. This revealed novel CSF biomarkers (i.e., complement 3, neuronal cell adhesion molecule, and platelet-derived growth factor) that appeared to improve the distinction between AD and non-AD cases (including cognitively normal subjects) compared with established AD biomarkers alone [70]. Another study using non-ADNI CSF samples and a slightly larger number of analytes (N = 190) in the Human Discovery MAP 1.0 panel supported the results of the prior study and found additional CSF biomarkers (i.e., cystatin C, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 3, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, pancreatic polypeptide, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, matrix metalloproteinase-10, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, growth related oncogene-alpha, fibrinogen, FAS, and eotaxin-3) to improve the diagnostic utility for AD [71]. In an RBM study using CSF samples from the ADNI cohort, several markers were associated with neurodegeneration in Aβ amyloid-positive subjects but not in Aβ amyloid-negative subjects. Lower levels of trefoil factor 3, VEGF, and chromogranin A, and a higher level of cystatin C were significantly associated with increased rates of neurodegeneration, indicating that these candidate markers potentially provide prognostic information and insights into AD pathobiology [72]. In another analysis of the multiplex RBM study of ADNI 1 CSF samples, high CSF apolipoprotein ε (apoE) levels were shown to be associated with a slower cognitive decline and decreased brain atrophy [126].

The RBM studies using ADNI CSF samples have been reported or are ongoing. RBM studies of targeted multiplex analysis of plasma proteins in ADNI samples supported the potential utility of a plasma proteome signature as a screening tool [73,74]. Of note, changes in the level of some plasma proteins (e.g., pancreatic polypeptide) were consistent with the results observed in CSF samples, and with results found in studies of non-ADNI cohorts [74,75]. These results also have been linked to genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [76] and provided novel insights into pathways and proteins that are associated with AD onset and progression.

5.3. Biomarkers quantified by multiple reaction monitoring tandem mass spectrometry

5.3.1. Amyloid beta (Aβ1–42)

Current immunoassays for Aβ measurement in CSF have several limitations including widely differing concentrations across the immunoassay platforms, using aliquots from the same samples, matrix effects, and lack of a CSF-based standard reference material and methodology [77]. The ADNI Biomarker Core continues to focus on assessments of CSF assays and other methodological issues related to the chemical biomarker studies conducted in the ADNI Biomarker Core at Penn. For example, Korecka et al. [78] established a calibrator surrogate matrix for the quantification of Aβ1–42 in human CSF. The analytical methodology was based on a 2-dimensional ultraperformance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (2D-UPLC/MS-MS) platform and validated quality control samples were prepared for the liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS-MS) methodology. The surrogate matrix was artificial CSF containing 4 mg/mL of bovine serum albumin which provided linear and reproducible calibration comparable with human pooled CSF as calibration matrix. The appropriate cleaning of the trapping and analytical columns provided daily trouble-free runs. Analyses of non-ADNI CSF Aβ1–42 showed that UPLC/MS-MS distinguished neuropathologically diagnosed AD subjects from healthy NCs. The concentration of Aβ1–42 measured by the 2D UPLC/MS-MS system was on average 4.5 times higher compared with the concentration determined by Luminex-AlzBio3 immunoassay, however, the clinical utility was comparable [78]. ROC curve and correlation analyses evaluated the diagnostic utility of this mass spectrometry method compared with the AlzBio3 immunoassay for the detection of the AD CSF biomarker Aβ1–42. Comparison of ROC curves for these two assays showed no statistically significant difference (P =.2229). Linear regression analysis of Aβ1–42 concentrations measured by this mass spectrometry-based method compared with the AlzBio3 immunoassay showed significantly higher but highly correlated results. Thus, this newly established surrogate matrix for 2D-UPLC/MS-MS measurement of Aβ1–42 provides selective, reproducible, and accurate results. The documented analytical performance and diagnostic performance for AD patients versus NCs supports consideration of this approach as a candidate reference method. This technique has also been evaluated in Round Robin studies, and compared with another mass spectrometry-based candidate RMP for CSF Aβ1–42 [79] with excellent results. Indeed the formal paperwork documenting the full details of this method has been submitted to the Joint Committee for Traceability in Laboratory Medicine as a candidate reference method.

5.3.2. Targeted mass spectrometry proteomic study

As the third part (the RBM study was the first, the BACE activity study the second) of the multiphased effort of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium to identify CSF-based biomarkers in AD and to qualify multiple peptides in CSF, a targeted mass spectrometry proteomic study was performed by a subgroup of the industry PPSB of ADNI in collaboration with the FNIH Biomarker Consortium. The targeted proteins and peptides were selected based on their relevance to AD and results from RBM studies. Using the final panel consisting of 567 peptides representing 221 proteins, 320 of 567 peptides were detectable in >10% of 306 ADNI CSF samples. Multiple approaches to statistical analyses assessed whether these analytes were associated with diagnosis (NC vs. MCI and AD) or with the progression of MCI patients to DAT. The results identified several potential diagnostic or predictive biomarkers. For instance, hemoglobin A, hemoglobin B, superoxide dismutase showed value for differentiating patients, and neuronal pentaxin-2, neurosecretory protein nerve growth factor (VGF), and secretogranin-2 predict the progression of MCI to AD. These data provide a novel tool to improve diagnostic accuracy, predict the disease progression, evaluate treatment efficacy, and early diagnosis of AD [80]. Further studies are warranted to confirm these initial studies using isotope labeled internal standards and validated quantitative multiple reaction monitoring liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (mrm LC/MS-MS) methodology and/or validated immunoassays.

5.4. Neurogranin

Synaptic pathology seems to occur early in AD [81,82] and is the best correlate to the cognitive dysfunction in AD patients. Neurogranin is a postsynaptic protein expressed in dendritic spines and is implicated in synaptic plasticity. In the post-mortem brain tissue from early onset and late-onset AD patients, a reduction of neurogranin levels was observed as compared with NC subjects [83]. A preliminary study measuring neurogranin in CSF by semiquantitative immunoblot analysis after enrichment showed a significant increase of neurogranin in the AD group compared with the NC group [84]. Based on this finding, using a newly developed monoclonal antibody and ELISA method, Kvartsberg et al. [85] supported the prior findings in two pilot cohorts and one independent validation cohort. They observed a marked increase in CSF neurogranin level in AD and found that high level of neurogranin in MCI stage subjects predicted the progression to AD particularly in Aβ amyloid-positive MCI patients during the follow-up period. These results suggested that CSF neurogranin may be a useful biomarker in addition to the established CSF AD biomarkers and has potential as a prognostic biomarker. To confirm these results, a study to measure CSF neurogranin using electrochemiluminescence technology in ADNI-1 samples has been conducted and data were recently uploaded to the ADNI database (https://ida.loni.usc.edu). The study demonstrated that CSF neurogranin levels in AD and progressive MCI patients, particularly in Aβ amyloidpositive patients, are higher than NC subjects, and that high baseline neurogranin levels in the MCI group predicted disease progression as reflected by cognitive decline, decrease of cortical glucose metabolism evaluated by FDG-PET, and hippocampal volume loss measured by MRI during follow-up period.

6. Progress in standardization of CSF AD biomarker measurements

A hallmark of ADNI is the longstanding commitment to the standardization of all methodologies used in this study. As discussed earlier there is a wide variance across centers using various immunoassays, especially for the measurement of Aβ1–42. An important ingredient of the process of standardization of these methods is collaboration with other organizations and laboratories to produce protocols that provide for this on a worldwide basis and with as much expertise as can be assembled. It is also worth noting that the Coalition Against Major Diseases has worked diligently to engage the discussion with the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) regarding the qualification of MRI-based hippocampal volume and CSF AD biomarkers for specified use in treatment trials. A formal letter of support was issued by the FDA on 2/26/2015 to CAMD “…to encourage the further study and use of CSF analytes Ab1-42, t-tau and phopsho-tau, as exploratory prognostic biomarkers for enrichment in trials for Alzheimer’s disease” (http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/UCM439713.pdf). A very important part of those formal discussions has been the foundational value of highly standardized preanalytical and analytical methodology [86]. A major commitment to improve on the standardization of CSFAD biomarker measurement, that the ADNI Biomarker Core participates in, is the joint effort involving AD biomarker researchers from academic, industrial, and governmental laboratories, under the auspices of the Alzheimer’s Association GBSC and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) and the Institute for Reference Materials and measurements (IRMM) [19]. Among the projects that are well-underway in this program are the joint study and development of mass spectrometry accuracy-based measurement of Aβ1–42 in CSF. Four participating centers including colleagues from Waters, PPD, the University of Gothenburg, and Penn, all use a common direct sample preparation method and clean-up step but different calibrator matrices and batches of Aβ1–42 standard [78,79,87,88]; all use isotope-labeled Aβ1–42 as internal standard. A pilot interlaboratory study was conducted in which aliquots from 12 CSF pools that covered a 4.5-fold range of Aβ1–42 concentration were analyzed for the documentation of interlaboratory variation: R2 = 0.98; average intralaboratory %CV of 4.7%; interlaboratory %CV of 12.2% that improved to 8.3% when adjusted using a common calibrator (Pannee J, et al., manuscript in review). This was a proof-of-principle study that showed very good concordance across the four laboratories and provided evidence that the use of a common calibrator could further improve interlaboratory agreement. That hypothesis was first tested in a two-center (UGot and Penn) study in which the participating laboratories used Aβ1–42 standard prepared by IRMM for calibrator preparation in each center, and the linear regression analyses of 10 CSF pools in this preliminary study (R2 = 0.99; Y = 1.021X-11.8) support the hypothesis that use of a common calibrator standard can provide for near-equivalent results in two different laboratories using two different calibration matrices [78,88]. The development of a reference Aβ1–42 standard has been underway by the IRMM during the past year and should have final Aβ1–42 mass assignment in the near future, pending final amino acid analysis-based mass analyses. This reference preparation has been used for a follow-up five-center interlaboratory study all using this common standard for calibrator preparation, and results of this study are expected to be available later this year, and provide a further test for the impact of use of a common calibration standard on interlab-performance. In addition to this interlaboratory study, the IRMM has organized a commutability study in which seven different immunoassays are compared with each other and to reference LC/MS-MS using aliquots from 32 different CSF samples. The results of these studies will hopefully provide the first major step toward the goal of true harmonization and ultimately, achievement of a common cut point for Aβ1–42. The IRMM working in concert with the GBSC team and direction of the IFCC CSF biomarker working group, chaired by Kaj Blennow, is developing a CSF-based certified reference material (CRM), consisting of aliquots of a large (5L) volume CSF pools, will have Aβ1–42 values assigned measured using qualified mrm/LC/tandem mass spectrometry reference methods. The CRM will have three different levels (low, intermediate, and high) of Aβ1–42 to cover the measuring range. Once available, this standard reference material would serve as a common commutable reference point for manufacturers of immunoassays to calibrate their standards against. This step could go a long way toward the goal of greatly improved agreement across the various immunoassay platforms (see Table 2 for basic information on new automated immunoassays).

Table 2.

Characteristics of immunoassays for measurement of AD biomarkers in CSF

| Parameter | Fluorimetric immunoassay |

ELISA | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay | ELISA | Single Molecule array (Simoa) immunoassay |

Chemiluminescent immunoassay |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Fujirebio | Fujirebio | Roche Diagnostics | MESO scale discovery (MSD) |

IBL International | ADx Neuroscience | Quanterix | Saladax Biomedical, Inc. |

| Instrument | Luminex—xMAP Technology |

Microplate reader with 450 ± 5 nm filter |

Cobas 6000 | MESO QuickPlex SQ and Sector S 600 |

TECAN Evolyzer with Plate Reader (450 nm) |

EUROIMMUN Analyzer I or I-2P |

Simoa HD-1 Analyzer |

VITROS EciQ/EciQ Immunodiagnostic System |

| Solid phase | Antibody coupled to microspheres |

Antibody precoated plate |

Magnetic beads | Antibody coated carbon electrodes integrated in 96- well plate |

Antibody precoated plate |

Antibody precoated plate |

Antibody coupled to paramagnetic beads |

Streptavidin solid surface microwell |

| Kit name/analyte | INNO-Bia AlzBio3 (Simultaneous quantification of Ab1–42, Tau, and p-Tau181P) |

INNOTEST β amyloid (1–42), INNOTEST hTauAg INNOTEST Phospho-Tau 181P |

Elecsys β-Amyloid (1–42), Elecsys tTau, ElecsyspTau (181P) |

Aβ Peptide Panel 1 Kit for Aβ 42, 40, and 38; MSD Multi-Spot Phospho (THR 231)/total Tau |

Aβ1–42 kit Aβ1–40 kit Total Tau kit Nonphosphorylated Tau kit |

Euroimmun Beta Amyloid (1–40), Euroimmun Beta Amyloid (1–42) Euroimmun Total Tau |

Aβ1–42 kit Aβ1–40 kit Total Tau kit |

Aβ1–42 kit Tau kit |

| Sample throughput |

36–38 samples in duplicate/day |

36–38 samples in duplicate/day/ assay |

170 samples/hour | 36–40 samples in duplicate/day/assay (one 96 wells plate) |

39–40 samples in duplicate/day/assay (one 96-well plate) |

38 samples in duplicate/day/assay (one 96-well plate) |

500 samples/day | Contact manufacturer |

| Reaction time | 15–19 hours | 15–19 hours | 18 minutes | 3 hours | 3.5–4 hours | 3.5 hours | No information | Less than 36 minutes |

| Sample volume | 75 µL of CSF/well | Abeta 1–42; 25 µL of CSF/well Total Tau: 25 µL of CSF/well p-Tau 181P: 75 µL of CSF/well |

40 µL of CSF to be diluted 1:4 |

50 µL of diluted CSF (1:8 for Aβ and 1:4 for Tau) |

5 µL to be diluted 1:20 per analyte for Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40, 25 µL to be diluted 1:4 for Total Tau, 50 µL to be diluted 1:2 for non-P-Tau |

15 µL of CSF, diluted for Aβ1–40 (1:21), 25 µL for Tau |

25 µL of CSF per analyte for Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40, 37.5 µL for Tau |

80 µL per analyte |

| Antibody for Aβ1–42, Aβ1–40, Aβ1–38 and Tau the capture antibody is followed by the detector antibody |

Aβ1–42: 4D7A3 and 3D6 Total Tau: AT120 and HT7 p-Tau181P: AT270 and HT7 |

Aβ1–42: 21F12 and 3D6 Total Tau: AT120 and BT2, HT7 p-Tau: HT7 and AT270 |

Biotinylated monoclonal anti- β-amyloid (X-42) and ruthenylated monoclonal anti- β-Amyloid (1-X) |

Aβ1–42: 12F4 and 6E10 or 4G8 Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–38: capture antibodies are specifically reactive to the C- terminus of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–38, respectively, and 6E10 or 4G8 is a detector antibody Tau and phospho Tau: mouse monoclonal antibodies |

Aβ1–42: antihuman Aβ(38–42) rabbit IgG and HRP conjugated antihuman Aβ(11– 28) mouse IgG Aβ1–40: antihuman Aβ(35–40) (1A10) mouse IgG and HRP conjugated antihuman Aβ(11– 28) mouse IgG Tau: mouse monoclonal antibody specific to amino acids 160– 180 of the Tau 441 and mouse monoclonal antibody specific to Tau; Non-P-Tau: 1G2 |

Aβ1–42: 21F12 and 3D6 Aβ1–40: 2G3 and 3D6 Total Tau: Adx201 and Adx215 |

Aβ1–42: 6E10 and H31L21 Aβ1–40: no data Total Tau: capture antibody coupled to paramagnetic beads to the mid-domain of tau, detection antibody (biotinylated) to the N-terminus |

Aβ1–42: carboxy terminus and amino terminus Tau: amino acid regions 217–224 and amino acid regions 192–204 |

| Quantitative range |

Aβ1–42: 51–1700 pg/mL Total Tau: 25–1400 pg/mL p-Tau181P: 9–260 pg/mL |

Aβ1–42: 62.5–4000 pg/mL Total Tau: 75–1200 pg/mL p-Tau 181P: 15.6–1000 pg/mL |

Aβ1–42: 200–1700 pg/mL |

Aβ1–42: 3.1–1271 (6E10) or 2.5–1271 (4G8) pg/mL Aβ1–40: 25–7000 pg/mL (6E10) or 20–6000 pg/mL (4G8) Aβ1–38: 60–8475 pg/mL (6E10) or 60–7500 pg/mL (4G8) Total Tau: 30–8000 pg/mL |

Aβ1–42: 7.81–125 pg/ mL Aβ1–40: 118–1880 pg/mL Tau: 25–1000 pg/ mL |

Aβ1–42: 126–2010 pg/mL Aβ1–40: 54–711 pg/mL (not corrected for dilution factor) Total Tau: 57–1462 pg/mL |

Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40: 0–100 pg/mL Total Tau: 0.026–360 pg/mL |

Aβ1–42: 5–2000 pg/ mL Tau: 12–4000 pg/ mL |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ, amyloid beta.

NOTE. The data are information provided by each company regarding the briefly described Parameters as of March 10, 2015. For more detailed and updated information please contact the vendor of the immunoassay of interest, and visit their websites. Fujirebio is in the process of developing a highly automated immunoassay platform, LumiPulse, based on chemiluminescence detection, 120 tests/hour, monotest cartridges, and Luminex Corporation has been developing immunoassays for CSFAβ1–42, and t-tau, with assay linearity for Aβ1-42 and t-tau of 78 pg/mL to 12541 pg/mL and 36 pg/mL to 2068 pg/mL, respectively, and further details will become available for these two immunoassay systems in the future.

7. Update on the blood-based AD biomarker development project

7.1. Blood-based proteome biomarkers

Although imaging and CSF biomarkers are the most promising tools to detect early AD in the controlled settings of a clinical study and demonstrate how AD biomarkers relate to AD pathophysiology, these modalities have the disadvantage of cost and invasiveness. It has been widely recognized that there remains a very compelling need for less costly and less invasive, and more widely available blood-based biomarkers for AD. Considering the multistage diagnostic process that is common in medical practice, simple and cost-effective blood-based biomarkers can enhance the utility of CSF and imaging biomarkers. One of the earliest blood-based biomarker studies were conducted by Ray et al. [89]. They identified 18 plasma proteins of 120 proteins using the predictive analysis of microarray that discriminated AD from nondemented NC subjects with close to 90% accuracy and predicted the progression of MCI with overall 81% agreement. Although this work has not been replicated, numerous profiling approaches using proteomic technology including RBM Human Discovery MAP system and multiplex array ELISA were conducted within and outside ADNI and some promising candidates were detected (e.g., N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide and pancreatic polypeptide) for early diagnosis and severity of AD [73–75,90–94]. A recent systematic review and replication study found that nine of the previous reported candidates were associated with AD-related phenotypes, and the association of pancreatic prohormone and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 with AD was replicated [95]. A recent study of pairwise gene–protein relationship integrating multiplex-panel plasma proteomics and targeted genes from GWAS data in ADNI and non-ADNI cohorts proposed the consideration of genetic variation when plasma protein levels are evaluated [96]. Therefore, combinations of these proteins appear to be promising directions to pursue for blood-based AD biomarkers, although validation studies should be conducted in large longitudinal population-based cohorts. Furthermore, these blood-based profiles of proteins will provide an insight for pathology and/or pathogenesis of AD [97]. However, the current blood-based proteomic or multiplex approaches as potential diagnostic and/or prognostic AD biomarkers are far from realistic clinical practice and validation studies are needed. Instead, these may play an increasing role in development of therapeutic targets or in monitoring response to therapy. Indeed, a recent study of subjects in the ADNI cohort using a multiplex immunoassay panel suggested that the incorporation of plasma biomarkers could yield high sensitivity and improved specificity, supporting their usefulness as a screening tool [73].

7.2. Plasma Aβ species

Like CSF, plasma Aβ species have been one of the first targets investigated, and are the most extensively studied peripheral marker for AD and still of substantial interest. However, the results of plasma level or ratio of Aβ species in sporadic AD, compared with NC, have been contradictory. Increased levels of Aβ1–42 in AD were reported [98], but another study reported the opposite [99,100]. In studies that classified subjects not only based on clinical diagnosis but also on AD-like CSF signature, that is, high t-tau and low Aβ1–42, the group of NC and MCI subjects with an AD-like CSF signature showed lower plasma Aβ1–42/Aβ1–40 ratio when compared with subjects with a normal CSF signature [101] and this also is the case for studies of MCI and AD patients [102]. Taken together, studies to determine plasma Aβ levels have not been useful as a diagnostic tool. Instead of diagnosis, when cognitive measures were used as outcome, the association between plasma Aβ levels or ratios and rate of cognitive decline was not consistent [101,103–105]. A recent study in the ADNI cohort measuring plasma Aβ species with other imaging and CSF biomarkers revealed that plasma Aβ1–42 showed only mild correlation with other biomarkers of Aβ pathology (CSF for soluble Aβ and Pittsburgh compound B (PiB)/AV-45 PET for insoluble Aβ measurement) and infarctions (white matter hyperintensity revealed by MRI), and a number of health conditions were associated with altered concentrations of plasma Aβ [30,106]. Weak association of plasma Aβ levels with cognitive changes consistent with previous conflicting results may be influenced by variable health factors [107]. It is not clear whether the level of plasma Aβ1–42 or Aβ1–40 reflects Aβ production and/or clearance in the brain because Aβ species in the blood are not all from the brain. Considering the production of Aβ1–42, β-secretase is a rate-limiting enzyme in Aβ-APP processing. Perneczky et al. reported that CSF β-secretase activity was not correlated with CSF Aβ1–42, plasma Aβ1–42, and plasma Aβ1–40, but with t-tau and p-tau in CSF, indicating that CSF levels of Aβ1–42 most likely reflect its deposition by decreased clearance rather than increased production in sporadic AD [68]. These studies and a recent review underlined the need for a better understanding of the biology and dynamics of plasma Aβ particularly in sporadic AD and for longer-term studies to determine the clinical performance of plasma Aβ [108]. However, with the improvement of the assay conditions, standardization of preanalytical and analytical processes, and full consideration of confounding factors affecting plasma Aβ levels, it is possible that plasma Aβ levels may become useful as a biomarker of brain Aβ amyloidosis and pharmacodynamics of Aβ-targeted therapy in AD.

7.3. Genetic biomarkers

The high heritability of late-onset AD (~80% heritability from twin studies) [109,110] derived a number of genetic association studies, and APOE ε4 allele is the best established genetic risk factor for risk to develop AD. The role of the ε4 allele as a modulator of the relationship between plasma Aβ and Aβ pathology in the brain (Aβ amyloid PET) was assessed in ADNI subjects. In APOE ε4− but not ε4+ subjects, there was a positive correlation between plasma Aβ1–40/Aβ1–42 ratio and [11C]PiB uptake [111]. Another study demonstrated that the expression pattern of plasma proteins determined by multiplex RBM panel was associated with APOE allelic status [73]. These results suggest that APOE genotype is associated with a unique plasma protein profile irrespective of diagnosis, indicating the importance of APOE genotype on plasma biomarker profiles.

Recent GWAS and meta-analysis studies identified and confirmed additional genetic variants associated with AD including CLU, PICALM, CR1, MS4A4A, CD2AP, CD33, EPHA1, BIN1 and ABCA7 and APOE [112–116]. Some specific single nucleotide variants in novel genes detected by robust sequencing technology (e.g., next-generation sequencing) were significantly associated with the progression of hippocampal atrophy in MCI patients without APOE ε4 allele [117,118]. These genetic data may have predictive value when combined with imaging and/or fluid biomarkers, and provide novel candidate therapeutic.target

7.4. Novel neuron-specific blood exosome biomarkers

Recently, two articles in non-ADNI cohorts were published and reported on the clinical utility to discriminate MCI/AD from matched NC subjects or patients with frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) using neural-derived blood exosomal proteins [119,120]. Fiandaca et al. measured AD-related proteins (i.e., Aβ1–42 and tau proteins) in neural-derived exosomes separated from peripheral blood (plasma), and found 96.4% accuracy for AD and 87.5% for FTD from NC subjects. They suggested that levels of phosphorylated tau and Aβ1–42 in extracts of neural-derived plasma exosomes predict the development of AD up to 10 years before clinical onset. Kapogiannis et al. examined phosphorylated type 1 insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1) related to insulin signaling pathways in neural exosomes in blood, and showed a complete separation of AD from NC subjects with normal cognition and without insulin resistance using an insulin resistance index (p-Ser 312-IRS-1/pan pY-IRS-1 ratio). This finding supported an observation of increased extent of IRS-1/-2 abnormalities in MCI and AD patients in a large number of autopsy-derived brain samples [121]. However, they showed a lack of any relationship of levels of the IRS-1 proteins to severity and stage of AD, and some overlap between AD and cognitively intact NC subjects with insulin resistance. These studies show promise to identify novel blood-based biomarkers specific to brain pathology that may give insights in the understanding of pathogenesis in preclinical stage of AD. However, further studies will be needed to validate these findings in independent clinical cohorts with larger numbers of subjects and with longitudinal clinical, CSF and imaging data including the ADNI cohort. Furthermore, the standardization of methodologies to extract neural-derived exosome and to measure exosomal proteins using ELISA will be required to confirm the validity of this approach.

7.5. Standardization of blood-based biomarker measurement

For the standardization of preanalytical variables for blood-based biomarker studies, the first set of guidelines was recently published by an international working group of the Standards for Alzheimer’s Research in Blood biomarkers (STAR-B) and Blood-Based Biomarker Interest Group (BBBIG) after initial overview regarding the status of the field [122,123]. The principle of the guidelines for preanalytical methods for blood-based AD biomarker by BBBIG/STAR-B working group are generally not specific but follow the regulatory good laboratory practice as defined by Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment in United States or international standards of Clinical Laboratory Standards Initiative. For blood-based biomarker studies in AD to progress, the adoption of guidelines to standardize preanalytical methods across cohorts and laboratories is required. Therefore, the BBBIG/STAR-B guidelines are a good starting point toward standardized methods that will be essential to move putative blood-based biomarkers forward in additional studies.

Changes in blood-based biochemical end points may not reflect pathology in the brain, compared with CSF signatures. Nevertheless, the recent literature suggests that several blood-based biomarkers or patterns will be useful to discriminate early AD and to predict the disease progression. However, the most important issues that remain are: adoption of standardized methodologies for sample collection and other preanalytical processes, method validation including establishing prospective quality control protocols and identification and control of matrix interferences consideration of how the diagnosis status is defined (e.g., pathology vs. clinical) and of comorbidities, confirmation of the results in independent studies, and independent assays [122]. In addition, blood-based biomarkers that can represent brain-specific pathology (e.g., neuron-specific exosome study) will warrant the clinical utility of blood-based biomarkers for the early detection of AD and prediction of the disease progression, and finally facilitate the clinical use of CSF and imaging biomarkers, the development of biomarkers closer to clinical routines and disease-modifying drug development. Regarding the role of the ADNI Biomarker Core in biomarker standardization, it should be noted that multiple collaborative efforts related to standardization consensus, discovery, or validation of novel blood-based biomarkers, collaborations with or support from international entities for blood-based biomarker development are emerging.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: The authors described progress made by the ADNI Biomarker Core, on use and application of standardized methodology, based on reviews of the literature using traditional (eg, PubMed) sources and meeting abstracts on CSF and plasma biomarker data generated by the core. Selected non-ADNI studies were included to enable wider interpretation across different populations of AD and control subjects.

Interpretation: Plaque and tangle pathology are reliably detected in prodromal and preclinical stages of AD using CSFAβ1-42 and tau protein concentration measurements and cutpoints established in the ADNI study. The trajectories over time for these biomarkers characterize progression to the pathologic state and heterogeneity across each ADNI cohort.

Future directions: With an emphasis on the use of automated and highly standardized methods, and including new biomarker tests, the Penn ADNI Biomarker Core will continue studies of baseline and longitudinal samples to enhance the predictive performance of CSF and plasma biomarkers. Continued collaboration using multimodal approaches are planned.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. This research was also supported by NIH grants AG10124. J.Q.T. is the William Maul Measy-Truman G. Schnabel Jr. M.D. Professor of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. J.-H.K. is supported by grants from the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korea Government (MSIP) Medical Research Center program (MRC No. 2014009392).

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

References

- 1.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White L, Small BJ, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki K, Abbott RD, et al. Recent clinical-pathologic research on the causes of dementia in late life: update from the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:224–227. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez-Isla T, Hollister R, West H, Mui S, Growdon JH, Petersen RC, et al. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:17–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savva GM, Wharton SB, Ince PG, Forster G, Matthews FE, Brayne C, et al. Age, neuropathology, and dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2302–2309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Smith CD, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, et al. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–368. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<358::aid-ana12>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruyama M, Shimada H, Suhara T, Shinotoh H, Ji B, Maeda J, et al. Imaging of tau pathology in a tauopathy mouse model and in Alzheimer patients compared to normal controls. Neuron. 2013;79:1094–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Tau imaging: early progress and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:114–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Meyer G, Shapiro F, Vanderstichele H, Vanmechelen E, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP, et al. Diagnosis-independent Alzheimer disease biomarker signature in cognitively normal elderly people. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:949–956. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]