Abstract

Background

Numerous techniques and materials are available for increasing the dorsal height and length of the nose. Microautologous fat transplantation (MAFT) may be an appropriate strategy for augmentation rhinoplasty.

Objectives

The authors sought to determine the long-term results of MAFT with the so-called one-third maneuver in Asian patients who underwent augmentation rhinoplasty.

Methods

A total of 198 patients who underwent primary augmentation rhinoplasty with MAFT were evaluated in a retrospective study. Fat was harvested by liposuction and was processed and refined by centrifugation. Minute parcels of purified fat were transplanted to the nasal dorsum with a MAFT-Gun. Patient satisfaction was scored with a 5-point Likert scale, and aesthetic outcomes were validated with pre- and postoperative photographs.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 45.5 years. The mean operating time for MAFT was 25 minutes, and patients underwent 1-3 MAFT sessions. The mean volume of fat delivered per session was 3.4 mL (range, 2.0-5.5 mL). Patients received follow-up for an average of 19 months (range, 6-42 months). Overall, 125 of 198 patients (63.1%) indicated that they were satisfied with the results of 1-3 sessions of MAFT. There were no major complications.

Conclusions

The results of this study support MAFT as an appropriate fat-transfer strategy for Asian patients undergoing primary augmentation rhinoplasty.

Level of Evidence: 4

Therapeutic

Therapeutic

Asian patients who elect to undergo augmentation rhinoplasty often present with concerns of a low dorsum and a short nose. Many implant types are available to address the concerns of these patients, including synthetic materials (eg, silicone and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE; Gore-Tex, W. L. Gore and Associates, Inc, Flagstaff, AZ]), autologous grafts (derived from cartilage, bone, fascia, and/or dermis), or xenografts.1 No implant material or technique is regarded as the standard in augmentation rhinoplasty so each surgical plan must be customized to the patient.

Both autologous grafts and synthetic implants can result in acceptable outcomes of rhinoplasty. In general, synthetic implants are associated with higher rates of complications, such as displacement and extrusion.2 Patients tend to prefer autologous cartilage and bone grafts because of the optimal biocompatibility and decreased risks of infection and extrusion with these grafts.3 However, autologous grafting can yield unfavorable outcomes such as inconsistent volume and uncontrollable shape of the graft, an unreliable absorption rate, and possible donor-site morbidity.3 In a meta-analysis, Peled et al4 determined that implantation of alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty was associated with an acceptable rate of complications. These authors advocated the placement of alloplastic implants when autogenous materials are unavailable or insufficient. However, specific guidelines have not been established for transplanting alloplastic materials.

Fat grafting was first described by Neüber5 in 1893 and continues to be a frequently performed procedure owing to the ease of fat harvest, the abundance of graft material available, and the lack of transplant rejection. However, fat survival and retention rates are unpredictable, and complications such as abscesses, cysts, nodulation, and neurovascular injury may occur.6 With years of extensive research and refinement of surgical techniques, structural fat grafting has become a reliable treatment strategy with acceptable clinical outcomes.7 Lin et al8 introduced the concept of microautologous fat transplantation (MAFT) in 2007. These authors subsequently demonstrated that MAFT yields reliable results in facial rejuvenation.9-13 In the present study, we performed MAFT with the so-called one-third maneuver in 198 Asian patients who underwent primary augmentation rhinoplasty.

METHODS

Review of Literature Addressing Fat Grafting to the Nose

A search on PubMed was performed on August 25 2015, with the keywords fat grafting and nose to identify patients treated from January 2000 to August 2015 who underwent fat grafting to the nose. Details of each study were summarized and primary findings were compared with the results of the present study.

Patients and Study Design

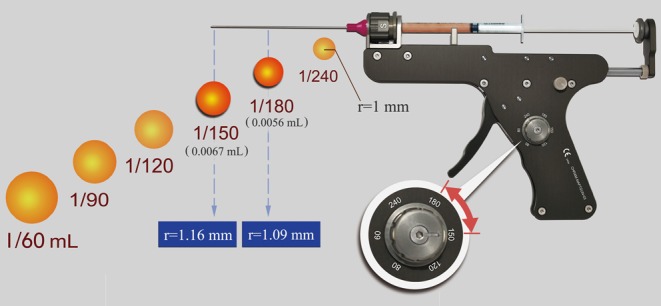

A total of 198 patients (180 women, 18 men) who presented for MAFT to correct their nasal dorsum from January 2010 to December 2014 were evaluated in a retrospective study. Patients who had undergone previous rhinoplasty, nasal implantation, or filler injections or had sustained trauma to the nasal dorsum were excluded from the study. Asian patients with thick and extendable dorsal skin for whom a second touch-up MAFT session was indicated to achieve favorable results were considered the best candidates for this study, though not all patients fit this criteria. It was not necessary to obtain approval from an institutional review board because fat grafting is a long-established procedure and because the microinjection device (MAFT-Gun, Dermato Plastica Beauty Co, Ltd, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; Figure 1) applied in this study has received ISO 13485 certification and CE marking. In addition, the establishment at which the MAFT-Gun is manufactured has undergone registration and listing with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Taiwan FDA. Patients provided informed written consent preoperatively for all surgical procedures and for anesthesia, intraoperative video recording, and photography. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

The microautologous fat transplantation (MAFT)-Gun. This device can be adjusted to precisely deliver 6 fat-parcel sizes (0.017 mL, 0.011 mL, 0.0083 mL, 0.0067 mL, 0.0056 mL, and 0.00420 mL).

Surgical Procedures

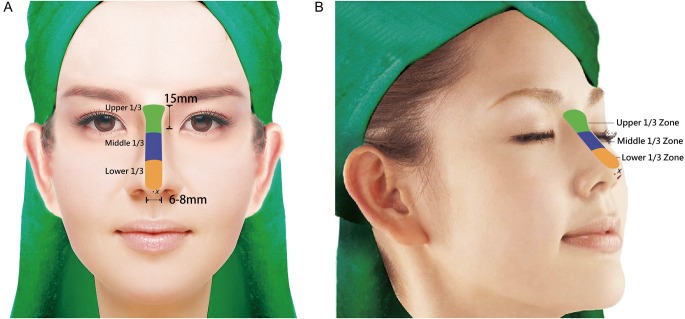

Videos 1, 2, and 3 demonstrate MAFT and may be viewed at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com. Preoperative markings were made with the patient seated. The recipient area for fat transfer was drawn in the shape of an I (width, 6-8 mm) from the nasal tip to a point approximately 15 mm above the intercanthal line (Figure 2) with a fan-shaped cephalic end. This pattern was divided into upper, middle, and lower zones (Figure 2). The total volume of fat to be injected was deposited as needed into these 3 zones.

Figure 2.

Computer-generated views of this 38-year-old woman depicting the one-third maneuver for MAFT. The recipient area is drawn as a 6- to 8-mm-wide I shape extending from the nasal tip to 15 mm above the intercanthal line. This marking is evenly divided into 3 zones: the upper third (green), the middle third (blue), and the lower third (orange). The point of insertion is indicated with an x. (A) Frontal view. (B) Oblique view.

All patients received total intravenous anesthesia before fat grafting. Appropriate local anesthesia was applied as needed at donor and recipient sites. Fat primarily was harvested from the lower abdomen. The donor site was infiltrated with a tumescent solution (10 mL of 2% lidocaine [20 mg/mL]:30 mL of Ringer's lactate solution:0.2 mL of epinephrine [1:1000]). Approximately 10-15 minutes after infiltration, fat was harvested from the donor site with a blunt-tip cannula (diameter, 2.5 or 3.0 mm; ≥1 holes sized 1 mm × 2 mm). The lipoaspirate volume was approximately equal to the volume of the tumescent solution to ensure that fat constituted a major proportion of the lipoaspirate. To minimize damage to the lipoaspirate, the plunger of a 10-mL syringe connected to a liposuction cannula was withdrawn to approximately 2-3 mL to maintain a negative pressure of 270–330 mm Hg.9

Lipoaspirates were processed and purified by centrifugation at 3000 rpm (approximately 1200 g) for 3 minutes as described by Coleman.7 This procedure minimized graft contamination due to environmental exposure and manual manipulation. Centrifugation also facilitated separation of the lipoaspirate into layers. The top layer contained oil from ruptured fat cells; the middle layer contained purified fat; and the bottom layer contained blood, cellular debris, and fluid.

The purified fat was carefully transferred into a 1-mL Luer-slip syringe by means of a transducer. The syringe containing purified fat was loaded into a MAFT-Gun (Figure 1) connected to an 18-gauge, blunt-tip cannula. The device was set by adjusting a dial to deliver fat parcels of 0.0067 mL (ie, 1/150 mL) to 0.0056 mL (ie, 1/180 mL) with each trigger deployment (Figure 1). A puncture incision was made on the nasal tip with a no. 11 scalpel blade (Figure 2). This insertion point was infiltrated with 0.3-0.5 mL of 2% lidocaine HCl with epinephrine (1:50,000). Fat then was transferred by depressing the trigger while withdrawing the MAFT-Gun. Fat was meticulously transplanted in 2-3 layers of the nasal dorsum from the deepest to the most superficial layers (ie, from the deep areolar plane to the vascular/fibromuscular plane to the subcutaneous areolar plane). During MAFT, downward traction was applied to successive zones of the nose with the surgeon's nondominant hand. First, traction was placed on the middle third of the nose while grafting the upper third. Next, traction was placed on the lower third of the nose (ie, the nasal tip) while grafting the middle third. Fat was transferred to the nasal tip last. The insertion wound was then closed with 1 suture (6-0, nonabsorbable).

Postoperative Care

Massage was avoided postoperatively. The recipient area was dressed with compressive garments and adhesive paper tape to alleviate swelling. Routine postoperative care, oral antibiotics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were administered for 3 days or as needed. The suture placed at the insertion site was removed 2-3 days postoperatively, and the sutures placed at the donor site were removed at 1 week postoperatively. All patients received routine follow-up at an outpatient clinic at 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively. Most patients were monitored beyond this duration. Photographs were taken at each visit for comparisons over time.

Assessment of Patient Satisfaction

At the final postoperative visit (ie, ≥6 months postoperatively), the nursing staff asked patients to indicate their subjective satisfaction with regard to the height and length of their nose. Responses were anonymous and satisfaction was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1, very dissatisfied; 2, dissatisfied; 3, neutral; 4, satisfied; and 5, very satisfied).

RESULTS

A search on PubMed returned 8 studies addressing fat grafting to the nose that we regarded as comparable to the present study. Specifically, these studies involved fat grafting (1) in the refinement of cleft nose;14 (2) as a complementary procedure during open rhinoplasty;15 (3) in the presence/absence of rhinoplasty;16 (4) as a means of restoring volume in reconstructive surgery;17 (5) to treat sequelae of rhinoplasty;18 (6) in terms of microfat injection to treat secondary nasal deformities;19 (7) to correct complications of rhinoplasty;20 and (8) as a potential cause of nasal-tip numbness after lipofilling.21 In Table 1, we summarize the key findings and the benefits and drawbacks of each of these studies.

Table 1.

Summary of Literature Review

| Authors (Year) | Title | Application of Fat Grafting | Study Duration | Total No. of Patients and No. Who Underwent 1, 2, or 3 Sessions; (Mean No. of Sessions) | No. of Men/No. of Women | Mean Age, Years (Range) | Mean Injection Volume, mL (Range) | Mean Follow-up, Months (Range) | Primary Results | Key Contributions | Comments by Authors of the Present Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | Microautologous Fat Transplantation for Primary Augmentation Rhinoplasty: Long-term Monitoring of 198 Asian Patients | Primary augmentation rhinoplasty for aesthetic purposes | 4 years | 198 patients; 126 (1 session) 70 (2 sessions) 2 (3 sessions); (1.4) |

18/180 | 45.5 (26-58) | 3.4 (2.0-5.5) | 19 (6-42) | Overall satisfaction rate of 63.1% | First article to describe a large series of patients who underwent fat grafting in aesthetic primary augmentation rhinoplasty with MAFT | MAFT is appropriate for primary augmentation rhinoplasty for aesthetic purposes |

| Duskova et al27 (2004) | Augmentation by Autologous Adipose Tissue in Cleft Lip and Nose. Final Esthetic Touches in Clefts: Part I | Reconstruction in cleft lip and nose to supplement a hypertrophic scarred lip and nasal columella | NS | 5 patients; (1 session) 3 (2 sessions) 1 (3 sessions) (2) |

1/4 | NS (26-38) | 4.3 (3-6) | 22 (NS) | All 5 patients have pleasing results | Described augmentation of the upper lip and columella by fat grafting is minimally invasive and results in physiologic shapes for the upper lip, nasal columella, and nasolabial angle | Small study but with promising results |

| Cárdenas et al28 (2007) | Refinement of Rhinoplasty with Lipoinjection | As an adjunct to open rhinoplasty | 2 years, 3 months | 78 patients 78 (1 session) (1) |

7/71 | NS (14-56) | NS (1-3) | 15 (1-36) | Results of 68 patients considered excellent, 9 good, 1 unsatisfactory | Determined that fat grafting can be applied to refine open rhinoplasty | Concludes that fat grafting is an adjunct procedure with open rhinoplasty |

| Monreal29 (2011) | Fat Grafting to the Nose: Personal Experience With 36 Patients | Primary augmentation, treatment of deformities after rhinoplasty, and in conjunction with rhinoplasty | 3 years, 3 months | 36 patients 33 (1 session) 2 (2 sessions) (1.1) |

NS | NS | Harvested 3-12 mL for lipoimplantation; 6-12 mL when combined with rhinoplasty | 7 (NS-14) | 80% (good-high) patient satisfaction, especially for deformities after rhinoplasty | Identified nasal danger zones and emphasized the importance of utilizing an 18-gauge, blunt injection needle | Only 18 of 36 patients (50%) presented for aesthetic purposes |

| Clauser et al30 (2011) | Structural Fat Grafting: Facial Volumetric Restoration in Complex Reconstructive Surgery | Volumetric restoration in complex reconstructive surgery | 4 years, 5 months | 23 patients NA (NA) |

NS | NS | 3.4 NS | NS | Good results and improvements in facial morphology, function, shape, and volume | Demonstrated the importance of structural fat grafting in facial volumetric restoration in complex reconstructive surgery | Only 23 of 57 fat grafting procedures were discussed |

| Baptista et al31 (2013) | Correction of Sequelae of Rhinoplasty by Lipofilling | To treat rhinoplasty sequelae, saddle nose, and sequelae of lateral osteotomy sequelae | 4 years | 20 patients 18 (1 session) 2 (2 sessions) (1.1) |

NS | 53 (NS) | 2.1 (1-6) | NS (18-24) | 18 patients satisfied to very satisfied, 2 required second rhinoplasty | Determined that lipofilling could be a simple and reliable alternative to correct imperfections following rhinoplasty | Correction of sequelae of rhinoplasty in 20 patients |

| Erol32 (2014) | Microfat Grafting in Nasal Surgery | As microfat transplantation in patients with secondary nasal deformities (group 1 slight irregularities; group 2, marked irregularities; group 3, severe deformities) | 5 years | 313 patients 264 group 1 patients (1-3 sessions) 38 group 2 patients (3-6 sessions) 11 group 3 patients (6-16 sessions) (NA) |

27/286 | 25.7 NS | 0.3-0.8 mL for minimal irregularities; 1-6 mL for major irregularities | NS (12-60) | Autologous microfat injection is safe and effective for correcting slight irregularities of the nose | Demonstrated that microfat grafting is effective for correcting minor irregularities of the nasal skin and is appropriate for patients who cannot undergo revision rhinoplasty | Multiple injections may be necessary for correction of nasal irregularities |

| Nguyen et al33 (2014) | Autologous Fat Grafting and Rhinoplasty | For correction of rhinoplasty sequelae | 6 years | 20 patients (1 session) 2 (2 sessions) (1.1) |

NS | 53 NS | 2.1 (1-6) | NS (18-24) | 18/20 patients satisfied to very satisfied | Emphasized the importance of utilizing a 21-gauge, 0.8-mm injection cannula vs an 18-gauge, 1.2 mm cannula | Relatively small study size to address correcting the sequelae of rhinoplasty |

| Huang34 (2015) | Does Sensation Return to the Nasal Tip After Microfat Grafting? | Evaluation of severity of numbness in the nasal tip after fat grafting | 4 years | 30 patients 30 (1 session) (1) |

0/30 | 20 (20-45) | NS (1-3) | NS (0-3) | Nasal tip sensation improved for 96.2% of patients at 12-week visit | Determined that nasal tip sensation will recover completely after fat grafting | Emphasized sensory recovery after fat grafting on tip only |

MAFT, microautologous fat transplantation; NA, not applicable; NS, not stated in study.

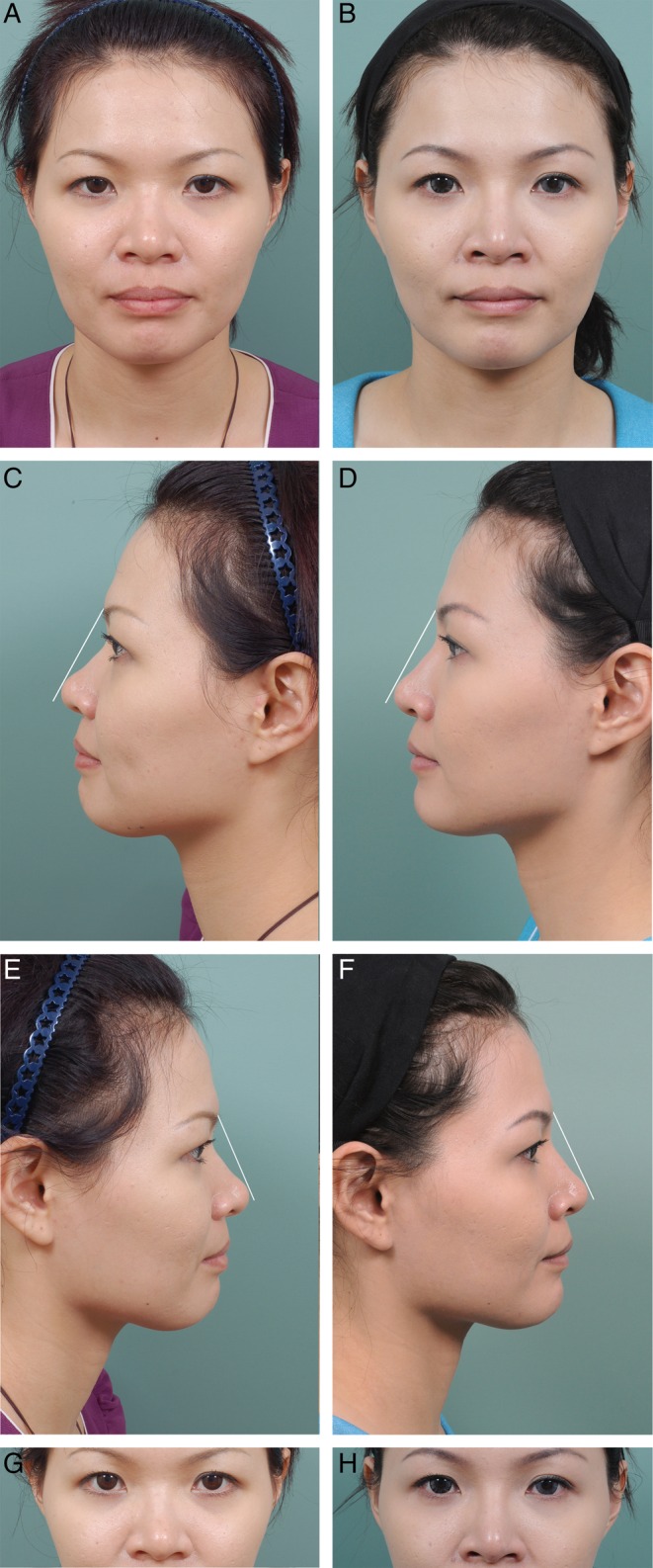

The mean age of the patients was 45.5 years (range, 26-58 years). The MAFT operating time, including the duration from harvesting to transplantation, lasted an average of 25 minutes (range, 18-30 minutes). The mean fat volume delivered per session was 3.4 mL (range, 2.0-5.5 mL). The estimated fat retention rate was ≤50% at postoperative 6 months. Patients were monitored for an average of 19 months (range, 6-42 months). No major complications (eg, infection, skin necrosis, nodulation, fibrosis, or asymmetry) were recorded. Of 198 patients, 126 patients (63.6%) underwent 1 MAFT session, 70 (35.4%) underwent 2 sessions, and 2 (1.0%) underwent 3 sessions. All patients rated their satisfaction at the final postoperative visit (Table 2). Patient satisfaction rates with 1, 2, or 3 MAFT sessions were 46.0% (58 of 126 patients), 92.9% (65 of 70 patients), and 100% (2 of 2 patients), respectively. Overall, 125 of 198 patients (63.1%) indicated that they were satisfied with the results of MAFT, with 52 (26.2%) stating that they were ‘very satisfied’ and 73 (36.9%) stating that they were ‘satisfied.’ In addition, most of the patients reported subjective improvements in skin texture postoperatively, including shrinkage of pores, improvements in wrinkles at the nasal root, a shiny and moisturized skin appearance, and longer maintenance of makeup. Four patients are presented in Figures 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Continued.

Table 2.

Patient Satisfaction After Augmentation Rhinoplasty With 1, 2, or 3 MAFT Sessions

| No. of Patients | Very Unsatisfied, No. of Patients (%) | Unsatisfied, No. of Patients (%) | Neutral, No. of Patients (%) | Satisfied, No. of Patients (%) | Very Satisfied, No. of Patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 session | 126 | 0 (0) | 5 (4.0) | 63 (50.0) | 38 (30.1) | 20 (15.9) |

| 2 sessions | 70 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (7.1) | 35 (50.0) | 30 (42.9) |

| 3 sessions | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Total | 198 | 0 (0) | 5 (2.5) | 68 (34.3) | 73 (36.9) | 52 (26.2) |

MAFT, microautologous fat transplantation.

Figure 3.

(A, C, E, G, I, K) This 28-year-old woman presented for augmentation rhinoplasty with fat grafting to increase the height of her nose. MAFT was performed to place a 3.5-mL fat graft (1.5, 1.0, and 1.0 mL in the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the nasal dorsum, respectively). (B, D, F, H, J, L) One year after a single MAFT session, the fullness and height of the nose were maintained.

Figure 4.

(A, C, E, G) This 32-year-old woman presented for augmentation of the height and length of her nose. She underwent 2 sessions of MAFT with the one-third maneuver with a 6-month period between sessions. A total of 3 mL of fat was grafted in the first session and 4.5 mL of fat was grafted in the second session. (B, D, F, H) Two years after the second MAFT session, the results are stable and effective and appear natural.

DISCUSSION

Many types of autologous grafts and synthetic implants are available for augmenting and recontouring the nasal dorsum.2-4 Silicone or ePTFE are common synthetic materials with which surgeons have demonstrated acceptable and consistent clinical results in certain patients.4 However, long-term outcomes of nasal implantation with synthetic materials have not been established. Complication rates for deviation, incompatibility, and skeletonization resulting from capsular contracture are unacceptably high with synthetic implants.2 Autologous grafts comprising cartilage, bone, dermis, and osseocartilaginous composites are preferable because of their superior biocompatibility and effectiveness.22-26 However, autologous grafts are associated with high rates of reabsorption and complications at the donor site, and few reports have addressed the long-term outcomes of implantation with these materials.27-33 No optimal strategy exists for augmentation rhinoplasty, and the choice of implant material and technique currently must be customized to the patient (Table 3).

Table 3.

Implantation With MAFT vs Other Materials in Primary Augmentation Rhinoplasty

| Synthetic Implant (Silicone/ePTFE) | Autologous Cartilage, Bone, Dermis | MAFT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous tissue | No | Yes | Yes |

| Immune rejection/inflammatory reaction | Possible/likely | Unlikely | Unlikely |

| Postoperative swelling and pain | High | Moderate | Minimal |

| Infection rate | High | Low | Very low (none in this series) |

| Deviation after operation | Likely | Occasional | Unlikely |

| Capsular contracture | Possible | Occasional | None |

| Marginal demarcation | Clear | Visible | Not visible |

| Improvement of skin texture | No | Not determined | Yes |

| Level of increasing dorsal height/length | Prominent, unnatural appearance | Prominent, natural appearance | May require several sessions |

| Projection of nasal tip | Easily achievable, potential skeletonization | Easily achievable, natural appearance | Difficult/unachievable |

| Donor-site morbidity | No | Scar | Minimal |

ePTFE, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene; MAFT, microautologous fat transplantation.

Coleman7,34 emphasized that structural fat grafting to regions with thin skin, such as the periorbital area, must involve delivery of minute fat parcels (ie, 0.033-0.020 mL). The nasal dorsum is characterized by relatively thin skin and limited space and is a challenging anatomic site for the insertion of fine fat parcels. However, implantation of larger fat parcels is more likely to yield dislodgement of the implant, nodulation, and skin irregularities. Studies that have addressed fat grafting in rhinoplasty generally involve lipoinjection in the nose, with most authors applying fat grafting for refinement of rhinoplasty or for nasal reconstruction (Table 1).14-21 We performed a literature review and identified 8 articles that address fat grafting to the nose. The results of these studies all further the field of nasal augmentation. However, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to apply fat grafting as a means to lengthen the nose and/or increase the dorsal height for aesthetic purposes.

In the present study, we applied our expertise with MAFT8-13 to primary augmentation rhinoplasty with the one-third maneuver. With the MAFT-Gun, we delivered minute parcels of fat (ie, 0.0067-0.0055 mL) in a layered and modular fashion to increase the dorsal height and length of the nose (Videos 1-3). For patients in this study who received >1 year of follow-up, the results of MAFT were stable (Figures 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, patients noticed benefits at the skin surface, such as improved texture. Similar findings of apparent skin rejuvenation after fat grafting have been reported by Mojallal et al35 and Hsu et al36 A prospective study involving a longer monitoring period is needed to confirm these findings.

MAFT was applied in this study to deposit fat parcels into 3 zones of the nose. This one-third maneuver involved fat grafting subsections of the nose while applying traction to the adjacent subsection such that fat was transferred successively to the upper, middle, and lower thirds. This strategy, akin to bricklaying, extended the dorsal length of the nose while maintaining its structural integrity and preventing cephalic retraction of the lower third of the nose. Although fat retention rates were ≤50%, satisfaction rates were acceptable for patients who underwent 1 MAFT session and were excellent for patients who underwent 2 or 3 sessions. According to Wu,37 the Asian nose comprises 5 well-defined layers of soft tissue overlying an osseocartilaginous framework. From most to least superficial, these layers include the skin, the subcutaneous areolar plane, the vascular-fibromuscular layer, the deep areolar plane, and the perichondrium/periosteum. In accordance with this anatomic basis, MAFT involves fat placement in 2-3 layers from the deepest to the most superficial planes (Videos 1-3).

Although the incidence of severe complications (eg, blindness) from fat grafting or filler injection is low, it is essential for the surgeon to possess extensive knowledge of the soft-tissue and vascular anatomy of the nose.37-39 In general, the surgeon performing MAFT should have mastery of nasal anatomy, should avoid vigorous maneuvers, and should closely observe the patient for signs and symptoms of complications. During the course of this study, we occasionally observed transient white coloration of the dorsal skin due to overinjection of fat, which caused vascular compression but not occlusion. When the color change did not resolve spontaneously within 3-5 minutes, 0.3-0.5 mL of injected fat was extruded from the insertion site.

Three factors inherent to MAFT help prevent severe complications. First, MAFT involves delivery of minute per-parcel volumes of fat (0.0056-0.0067 mL). Second, fat was injected with a cannula (18 gauge, blunt tip, 1.2 mm in diameter) that was larger than the lumen of the vessels near the nasal dorsum and therefore precluded vascular injury. Although the cannula penetrated the vessels incidentally, the intravascular injection volume (0.0056–0.0067 mL) would not occlude the lumen. Third, the extrusive pressure of the fat parcels was very low (2-4 mm Hg). This safeguard was in place to prevent a spike in local pressure that could propel a fat parcel upstream to the ophthalmic artery where it could occlude the central retinal artery and cause visual disturbance or blindness.9,37-39

The present study is associated with several limitations. Adequate projection of the nasal tip and sufficient length or height of the nasal dorsum were difficult to achieve with a single session of MAFT. However, this is also a limitation of synthetic implants and autologous cartilage grafts. The results of our subjective measure of patient satisfaction were favorable, but an objective validation of MAFT is lacking from this study. Future work should include 3-dimensional imaging of MAFT results over time to evaluate fat retention and survival.

CONCLUSIONS

Fat grafting cannot be applied universally to address the concerns of Asian patients who present for rhinoplasty. However, the results of this study support the utility of MAFT with the one-third maneuver to increase the height and length of the nose in primary augmentation rhinoplasty. Favorable outcomes were obtained for patients with thick, elastic skin who presented with a short, flat nose and underwent ≥2 MAFT sessions. Our results indicated that patients were satisfied with the long-term results of MAFT.

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material located online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Disclosures

Dr T-M Lin owns the patent right for the microautologous fat transplantation (MAFT)-Gun and is the scientific adviser of Dermato Plastica Beauty Co, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, which is the manufacturer of the MAFT-Gun. The other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jang YJ, Yi JS. Perspectives in Asian rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;302:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee MR, Unger JG, Rohrich RJ. Management of the nasal dorsum in rhinoplasty: a systematic review of the literature regarding technique, outcomes, and complications. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2011;1285:538e-550e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wee JH, Park MH, Oh S, Jin HR. Complications associated with autologous rib cartilage use in rhinoplasty: a meta-analysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;171:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peled ZM, Warren AG, Johnston P, Yaremchuk MJ. The use of alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty surgery: a meta-analysis. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2008;1213:85e-92e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neüber. Fettransplantation. Bericht über die Verhandlungen der Dt Ges f Chir Zbl Chir. 1893;22:66. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khawaja HA, Hernández-Pérez E. Fat transfer review: controversies, complications, their prevention, and treatment. International Journal of Cosmetic Surgery and Aesthetic Dermatology. 2002;42:131-138. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;185:386-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin TM, Lin SD, Lai CS et al. The treatment of nasolabial fold with free fat graft: preliminary concept of micro-autologous fat transplantation (MAFT). In: Second Academic Congress of Taiwan Cosmetic Association, Taipei, Taiwan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou CK, Lin TM, Chiu CH et al. Influential factors in autologous fat transplantation - focusing on the lumen size of injection needle and the injecting volume. J IPRAS. 2013;9:25-27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou C, Lin TM, Chou CK, Lin TY, Lai CS, Lin SD. Micro-autologous fat transplantation (MAFT) for the correction of sunken temporal fossa - long term follow up. J IPRAS. 2013;9:28-29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin TM, Lin TY, Chou CK, Lai CS, Lin SD. Application of microautologous fat transplantation in the correction of sunken upper eyelid. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;211:e259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin TM, Lin TY, Huang YH et al. Fat grafting for re-contouring the sunken upper eyelids with multiple folds in Asians—novel mechanism for neoformation of double eyelid crease. Ann Plast Surg. 2015 Dec 15. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000668 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin TM. Total Facial Rejuvenation with Micro-Autologous Fat Transplantation (MAFT). In: Pu LLQ, Chen YR, Li QF et al., eds. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery in Asians: Principles and Techniques, 1st ed. St. Louis, CRC Press; 2015:127-146. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duskova M, Kristen M. Augmentation by autologous adipose tissue in cleft lip and nose. Final esthetic touches in clefts: part I. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;153:478-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cárdenas JC, Carvajal J. Refinement of rhinoplasty with lipoinjection. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;315:501-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monreal J. Fat grafting to the nose: personal experience with 36 patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;355:916-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clauser LC, Tieghi R, Galiè M, Carinci F. Structural fat grafting: facial volumetric restoration in complex reconstructive surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;225:1695-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baptista C, Nguyen PS, Desouches C, Magalon G, Bardot J, Casanova D. Correction of sequelae of rhinoplasty by lipofilling. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013:666;805-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erol OO. Microfat grafting in nasal surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;345:671-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen PS, Baptista C, Casanova D, Bardot J, Magalon G. Autologous fat grafting and rhinoplasty. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2014;596:548-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L. Does sensation return to the nasal tip after microfat grafting? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;737:1396, e1-1396, e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachs ME. Enbucrilate as cartilage adhesive in augmentation rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;1116:389-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman WS, Gilbert RW. Augmentation in rhinoplasty--a personal view. J Otolaryngol. 1985;142:107-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erdogan B, Tuncel A, Adanali G, Deren O, Ayhan M. Augmentation rhinoplasty with dermal graft and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;1116:2060-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orak F, Baghaki S. Use of osseocartilaginous paste graft for refinement of the nasal dorsum in rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;375:876-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohrich RJ, Muzaffar AR. The Turkish delight: a pliable graft for rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;1056:2242-2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerrerosantos J, Trabanino C, Guerrerosantos F. Multifragmented cartilage wrapped with fascia in augmentation rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;1173:804-812; discussion 813-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang YJ, Wang JH, Sinha V, Song HM, Lee BJ. Tutoplast-processed fascia lata for dorsal augmentation in rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;1371:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gentile P, Cervelli V. Nasal dorsum reconstruction with 11th rib cartilage and auricular cartilage grafts. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;621:63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park CH, Kim IW, Hong SM, Lee JH. Revision rhinoplasty of Asian noses: analysis and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;1352:146-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brent B. The versatile cartilage autograft: current trends in clinical transplantation. Clin Plast Surg. 1979;62:163-180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HK, Rhee SC. Augmentation rhinoplasty using a folded ‘pure’ dermal graft. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;245:1758-1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swanepoel PF, Fysh R. Laminated dorsal beam graft to eliminate postoperative twisting complications. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;94:285-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting: more than a permanent filler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 suppl):108S-120S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mojallal A, Lequeux C, Shipkov C, Breton P, Foyatier JL, Braye F, Damour O. Improvement of skin quality after fat grafting: clinical observation and an animal study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;1243:765-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu VM, Stransky CA, Bucky LP, Percec I. Fat grafting's past, present, and future: why adipose tissue is emerging as a critical link to the advancement of regenerative medicine. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;327:892-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu WT. The Oriental nose: an anatomical basis for surgery. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1992;212:176-189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beleznay K, Carruthers JD, Humphrey S, Jones D. Avoid and treating blindness from fillers: a review of the world literature. Dermatol Surg. 2015:4110:1097-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park SW, Woo SJ, Park KH, Huh JW, Jung C, Kwon OK. Iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012:1544:653-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]