Abstract

Radiologists aspire to improve patient experience and engagement, as part of the Triple Aim of health reform. Patient engagement requires active partnerships among health providers and the patient, and rigorous teamwork provides a mechanism for this. Patient and care team engagement are crucial at the time of cancer diagnosis and care initiation, but are complicated by the necessity to orchestrate many interdependent consultations and care events in a short time. Radiology often serves as the patient entry point into the cancer care system, especially in breast cancer. It is uniquely positioned to play the value-adding role of facilitating patient and team engagement during cancer care initiation. The 4R approach previously proposed for optimizing teamwork and care delivery during cancer treatment (Trosman, JOP 2016), could be applied at the time of diagnosis. The 4R approach considers care for every cancer patient as a project, using Project Management to plan and manage care interdependencies, assign clear responsibilities and designate a Quarterback function. We propose that radiology assume the Quarterback function during breast cancer care initiation, developing Care Initiation Sequence, as a project care plan for newly diagnosed patients, and engaging the patient and her care team in timely, coordinated activities. After initial consultations and treatment plan development, the Quarterback function is transitioned to surgery or medical oncology. This model provides radiologists with opportunities for value-added services and solidifying radiology’s relevance in the evolving healthcare environment. To implement 4R at cancer care initiation, it will be necessary to: change the radiology practice model to incorporate patient interaction and teamwork; develop the 4R content and local adaption approaches; and enrich radiology training with relevant clinical knowledge, patient interaction competence and teamwork skillset.

Keywords: cancer, breast Cancer, breast cancer diagnosis, patient engagement, teamwork, team-based care, models of care, radiology care delivery

BACKGROUND

The U.S. healthcare system is undergoing seismic changes, guided by the Triple Aim of health reform: (1) improving population health, (2) reducing healthcare costs (3) enhancing patient experience.1 The radiology community has embraced the new paradigm, aspiring to play a relevant, value-adding role in the evolving healthcare environment.2,3 While radiologists are well-positioned to contribute to the first two aims, their traditionally non-patient-facing practice model makes the third aim - improving patient experience – challenging.2–5 Committed to overcoming this challenge, the American College of Radiology (ACR) launched initiatives to identify and meet patients’ needs and expectations for radiologic care,2 as well as expand the role of radiology into value-adding services.3,6

Patients are no longer passive recipients of care, but active, informed, influential participants.7–9 Thus, patient engagement is central to improving their experience and achieving the Triple Aim.10 Patient engagement refers to patients, families and health professionals working in active partnership to improve health and healthcare.11 This relationship requires not only reframing how patients engage with providers, but also how providers are engaged with patients and each other.9,12 A team-based approach is an effective mechanism to forge partnerships between patients and providers9 and improve care delivery.13,14 This aligns with the ACR vision, which includes teamwork as a platform for improving satisfaction of both patients and clinicians up- and downstream from radiology.3

Cancer is a disease for which patient engagement and a team-based approach are particularly important, and where radiology has a unique opportunity to demonstrate value, given its involvement throughout the cancer care continuum. In many health systems, cancer care is complex, fragmented and poorly coordinated7,15–18 compelling patients to manage their own care and act as a conduit across clinical domains.7,19 This hardly constitutes patient engagement, as defined above. A team-based approach is considered integral in overhauling this “system in crisis”18 but remains underutilized in oncology.20,21 To address this gap, in 2015, National Cancer Institute (NCI) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) launched the NCI-ASCO Teams in Cancer Care Delivery Project.20 The Project aimed to explore how intentional, rigorous teamwork can be applied to the continuum of cancer care, and to initiate development of innovative approaches for implementing teamwork in oncology care delivery.20

Within this project, Taplin et al highlighted barriers to patient care and engagement during breast cancer diagnosis and examined how intentionally-designed teamwork could improve the diagnostic process and patient experience.22 Similarly, Trosman and colleagues focused on care breakdowns and opportunities for teamwork during breast cancer treatment.23 However, to our knowledge, the care initiation phase – from diagnosis to start of treatment – remains unexplored in this context.

Patient engagement at care initiation is crucial, yet especially difficult: patients are devastated by the diagnosis,7 overwhelmed by the complexity of care planning,24 and struggle shuttling between often disconnected specialties.25 This results in care delays and breakdowns26,27 and patient dissatisfaction.7,22 Launching teamwork at care initiation may address these challenges. For a number of cancers, radiologists play a key role during diagnosis, post-diagnostic workup and care initiation, often serving as the patient entry point into the cancer care system.3 They have a distinctive opportunity in this setting to play a role in facilitating teamwork and enabling patient engagement, which expands their traditional scope into value-added activities.

Building on previous work by Taplin et al22 and Trosman et al,23 this article explores barriers to optimal care during breast cancer care initiation and how they could be addressed by teamwork and patient engagement, highlighting the potential role of radiology in the optimized process. We analyze how an innovative 4R Approach - Right Information and Right Care for the Right Patient at the Right Time© - for facilitating teamwork in cancer care, introduced by Trosman et al, may be applied to breast cancer care initiation and a value-added role for radiology. We focus on breast cancer because of the key part radiology plays as the point of diagnosis and entry into the cancer care system, as well as during treatment and survivorship. Applying 4R at breast cancer diagnosis may potentially serve as a model for other cancers where radiology plays a similar part.

METHODS

We use the case-based method utilized by the NCI-ASCO Teams Project for systematically examining how principles of teamwork can improve cancer care delivery. This includes: describing specific care delivery challenges; illustrating them using patient cases, describing relevant aspects of teamwork and analyzing how they could address challenges highlighted in the cases. Our case studies are based on challenges documented in the literature.

We follow the NCI-ASCO Project framing of systematic, intentional teamwork, which extends far beyond multidisciplinary conferences and focuses on rigorous team-based design of the care planning and delivery processes to collectively achieve common goals.20,22 This design incorporates patients, families and or caregivers.11 In this paper, reference to patients includes family and/or caregivers.

FOUR CHALLENGES OF CANCER CARE DELIVERY AND TEAMWORK

We focus on four interrelated challenges that exist throughout cancer care delivery, including diagnosis and care initiation. They negatively impact patient care and impede effective teamwork and patient engagement (See summary and examples in Table 1).

Table 1.

Challenges of Cancer Care Delivery and Teamwork, and Principles of the 4R Model

| Challenge | Description and Examples | Project Management elements addressing the challenge | Corresponding 4R Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timing and sequencing of interrelated care events | Management of synchronous tasks involving information exchange and mutual adjustment in action28,29 | Project plan identifies the systematic, coordinated schedule of interdependent events, with timing, sequencing and dependencies46 | Care Sequences, as patient care project plans, with timing & sequencing of care events across all relevant domains |

| Unclear or misplaced responsibilities | Relevant to “cross-specialty”, or specialty-independent care | Team members are assigned responsibilities for each event in the project schedule61,62 | Cross-domain 4R care project team, acting in accordance with the Care Sequence, with all members have explicit responsibilities |

| Lack of one cross-domain care plan | One care plan created at diagnosis, reflecting multi-modality care through end of treatment, including surgery, radiation, impacting, systemic therapy, supportive and psychosocial care19 | Project plan includes inter-disciplinary groups and sub-teams61 | Care Sequence represents the care plan for the entire care episode, from diagnosis through treatment, or into hospice |

| Absence of physician in charge across domains along the care continuum | Physicians typically perform this role only within their domain (e.g. surgical care, systemic oncology care), or across domains, but only while the patient is within their domain.7,9 | A project requires a Project Lead with explicit responsibilities63 | Quarterback function (physician / nurse tandem) acts across care domains along a patient’s care continuum. Responsible for creating patient-specific Care Sequence from templates and ensure ongoing engagement of the Care Team. |

Timing and Sequencing of interrelated care

Managing the timing and sequencing of interrelated tasks across team members is considered a cornerstone of teamwork.28,29 Contemporary, multi-modality cancer care is highly interdependent across specialties and requires that interrelated care events be delivered not only at the “right” time, but also in the “right” sequence. However, orchestrating this across clinical domains is complicated and difficult.9,19,30 Failure to effectively time/sequence interdependent care impedes teamwork among providers31,32 and causes care delays, breakdowns and changes in care trajectories.16,22,23,33,34

Unclear or misplaced responsibilities

Effective teamwork requires that team members formally agree and accept responsibilities for tasks.35–37 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the NCI-ASCO Project call for identifying and documenting responsibilities for key care components for each cancer patient.18,19,22 In a given institution, identifying responsibilities for definitive cancer care (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, imaging or radiation) is relatively straightforward, as this care is tied to particular specialties. However, responsibilities for other, less specialty-dependent care are often unassigned or implicitly assumed. For example, medical oncologist, surgeon or palliative clinician may conduct the “goal-of-care” discussion; similarly, multiple specialists review patient’s family history and could identify hereditary cancer risk and provide genetics referral. In the absence of formal responsibility, these tasks are missed, performed inconsistently, or are conducted at the “wrong” time and sequence relative other tasks.15,22,38

Lack of one cross-domain care plan

Task timing/sequencing and responsibilities are meaningful only in the context of a team’s common workplan.36 In cancer care, clinical domains develop their respective plans for patients, e.g. a surgical plan, a systemic therapy plan. However, patients rarely receive one overall care plan outlining the roadmap from diagnosis through multi-specialty treatment. The IOM urged the development of a comprehensive, written, patient-centric care plan at diagnosis, which guides the patient and the care team through the cancer care continuum.18,24 The plan facilitates patient and care engagement and enables timely, coordinated care.19 A patient without a care plan is likened to a “pilot taking off without a flight pattern”.24

Absence of physician in charge across domains along the care continuum

Team leadership is a key principle of successful teamwork.39 and is considered an important element of a cancer care team.9 Cancer patients ask who will lead their care team, and want to have one physician in charge of their care.7,18,19,40,41 While specialists may play the lead role within their respective clinical areas, e.g. during surgery or chemotherapy, there is rarely a physician who formally acts as a team lead across domains from a patient’s diagnosis through treatment.7,18,40 Patients seek one physician in charge so that s(he) provides, among other things, continuity, resolution to inconsistent recommendations across domains, and serves as the “last resort” for patient questions and problems.7 Nurse-navigators and case managers are effective in helping the patient travel through the maze of cancer care, but this function cannot substitute rigorous teamwork and physician leadership.19,42

CASE STUDIES ILLUSTRATING CHALLENGES AT BREAST CANCER CARE INITIATION

Case A – Genetic Assessment Prior to Breast Cancer Surgery

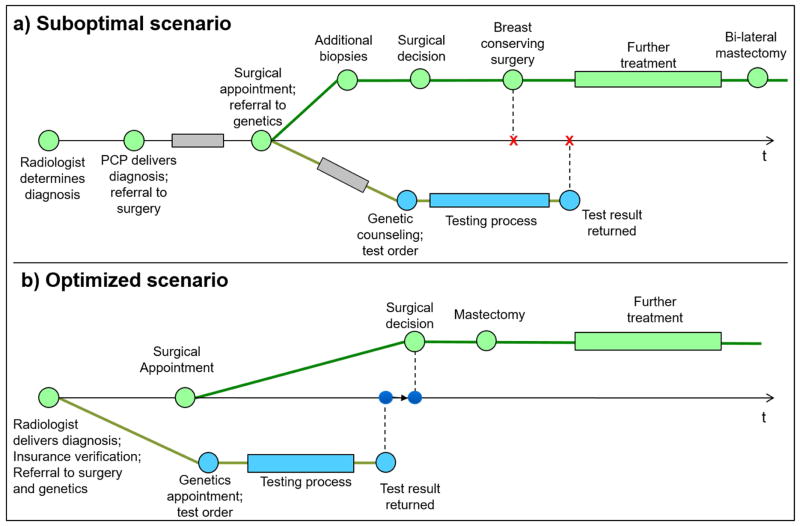

Patient A receives breast cancer diagnosis (clinical stage II) from her primary care physician (PCP), after a delay in radiology-PCP communication and PCP appointment scheduling (Figure 1a). Surgeon consultation is also delayed, due to insurance issues. Based on A’s family history, Surgeon refers her to genetic counseling, as surgical approach may be altered depending on results. However, genetic assessment is prolonged, due to by lack of access to the geneticist and long wait time for results, along with insurance logistics and appointment delays. Breast MRI identifies additional indeterminate lesions that need to be evaluated with additional biopsies if the patient is seeking breast conservation. Additional lesions are biopsied and are determined benign. A, anxious to move forward and have therapy initiated proceeds with a lumpectomy, and receives genetic results after surgery, indicating high risk of hereditary breast cancer. She undergoes adjuvant systemic therapy and decides to undergo bilateral mastectomies 9 months after.

Figure 1. Case of Patient A. Genetic Assessment Prior to Surgery.

Insurance eligibility and network verification issues and other delays

Insurance eligibility and network verification issues and other delays

PCP – Primary Care Physician

Diagram is not to the actual time scale

Here, genetic assessment is not timed/sequenced relative to surgery and insurance verification is not synchronized with consultations and tests. Responsibilities for insurance verification and genetics referral are not clear, and are misplaced in timing. There is no overall care initiation plan shared between A and her providers, and no one who takes overall charge of her care.

In an optimized, streamlined scenario (Figure 1b), the radiologist conveys the diagnosis to A, and creates a care initiation plan, including all initial consultations. Radiology staff (e.g.; breast cancer navigator) facilitates the necessary insurance verification (e.g. by involving a hospital-based financial counselor) and referrals to surgery and genetics, thus allowing sufficient time to complete genetic assessment in time for surgical decision. The plan is shared between A and her providers; A understands the importance of making timely appointments. Radiology staff conveys to genetics the urgency of A’s testing and necessity to expedite. Informed by genetic results, and after consultations with her surgeon, reconstructive surgeon, radiation oncologist and other relevant specialists, A proceeds directly to bilateral mastectomies, thus avoiding unnecessary biopsies and lumpectomy.

It is important to note that in the optimized scenario, the radiologist is not making cancer treatment recommendations, but provides timely referrals to specialties, who work with the patient to make the treatment decisions.

Case B – Neoadjuvant therapy

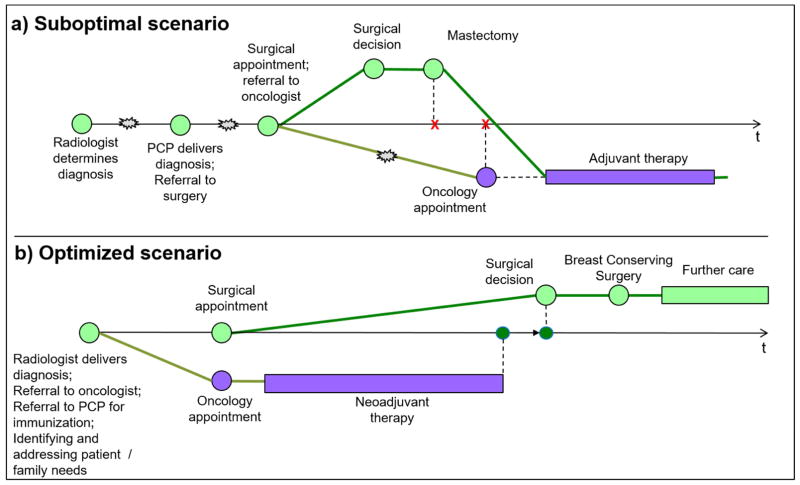

Patient B, a single mother of two, is diagnosed with clinical stage IIB breast cancer (Figure 2a). Her diagnosis is delayed by Radiologist/PCP communication, and her consultations along the way are impacted by childcare and work schedule conflicts, as well as surgeon and medical oncologist appointment delays. Her surgeon determines the appropriate surgical approach and proceeds to mastectomy. Post-mastectomy evaluation by medical oncologist determines that the patient could have benefited from neoadjuvant systemic therapy.

Figure 2. Case of Patient B. Neoadjuvant Therapy.

Patient delays due to childcare and work schedule issues (present in scenario a, but resolved in scenario b)

Patient delays due to childcare and work schedule issues (present in scenario a, but resolved in scenario b)

PCP – Primary Care Physician

Diagram is not to the actual time scale

Here, the medical oncology path is not synchronized with the surgical path, there is no overall care plan, and no one is in charge of B’s care. There is lack of coordination with social work to address B’s childcare issues. The surgeon assumes the responsibility for medical oncology referral, but it is made too late relative to the surgical process, and doesn’t allow initiation of neoadjuvant treatment in a timeframe appropriate for B.

In an optimized scenario (Figure 2B), radiologist conveys the diagnosis to B, works with her to create a care initiation plan and refers her to surgery, medical oncology and other relevant specialties, according to the plan. B’s childcare issues are also identified at this time, and a social worker helps her proactively address them. B and her providers use the care initiation plan; her oncologist appointment is scheduled in time to allow for neoadjuvant therapy decision and preparation. After neoadjuvant therapy, B receives a breast conserving surgery.

As in Case A, the radiologist is not making cancer treatment recommendations, but provides timely referrals to specialties for treatment decisions.

ADDRESSING CHALLENGES OF CANCER CARE DELIVERY AND TEAMWORK – THE 4R APPROACH

The challenges described and illustrated above present barriers to systematic rigorous teamwork, undermine cancer patient engagement, cause care breakdowns and result in suboptimal course of treatment. These issues are further exacerbated when a patient obtains care from multiple institutions or practices, which is common in oncology.7,43

However, these issues are not unique to oncology or healthcare: a vast array of modern industries depends on rigorous, systematic teamwork, from construction and information technology to fashion design. One of the disciplines broadly and successfully employed to manage complex, multi-disciplinary teamwork is Project Management.44–46 Although its use in care delivery has been proposed,38,47,48 it remains underutilized in this context. Project management is uniquely suited to manage teamwork in oncology.23 It inherently addresses the four care delivery challenges highlighted above (Table 1). It provides a systematic, yet flexible approach to structuring teamwork and adapting to different care settings and environments. Also, it is familiar to many patients from their line of work, and to many providers from institutional quality improvement projects.32,49

We previously proposed the 4R approach to facilitate rigorous, patient-centric teamwork in oncology, leveraging the Project Management discipline23,30,38 (Table 1). Under this approach, care for a cancer patient is managed as a project, using a care project plan (“Care Sequence”), which specifies timing and sequencing of interdependent care events across clinical domains relevant to the patient’s care. A Quarterback function is established as a tandem of a physician and a nurse. The Quarterback function creates the Care Sequence from a pre-developed template for a newly diagnosed patient and identifies the 4R care team which will use the Care Sequence in the process of care delivery. Within the Quarterback function, the physician determines clinical recommendations and/or referrals to relevant specialties to be included in the Care Sequence; and serves as an ongoing physician resource for the patient (e.g. to resolve conflicting clinical recommendations across specialties). The nurse facilitates the development of the Care Sequence, working with the physician and patient, and organizes patient care according to the Sequence. This includes engaging members of the care team at the “right” time and in the “right” sequence, and updating the Care Sequence if needed. Many institutions employ a patient nurse navigator who helps a breast cancer patient follow her care plan across different specialties once a plan is established, but typically does not devise the care plan. In the 4R model, a navigator could also assume the responsibility of the nurse who works with the quarterback physician and patient to devise the Care Sequence as the patient care project plan.

The Care Sequence will specify responsibilities for each event in the project plan. The patient, family or caregiver will be a team member with responsibilities for specific tasks in the sequence, e.g. making timely appointments and adhering to the treatment course. The 4R structure and principles become the backbone for provider-patient teamwork and the mechanism for team and patient engagement.

APPLYING 4R AT BREAST CANCER CARE INITIATION AND THE ROLE OF RADIOLOGY

Applying the 4R approach at cancer diagnosis could greatly benefit the patient and her providers, directing initial steps in care and providing the patient with some level of certainty and control at this trying time. However, constructing the Care Sequence may be premature at diagnosis, as additional workup is often necessary, as well as treatment decisions reached after initial consultations with specialists. For example, a key decision necessary to construct a Care Sequence is whether the patient will undergo neoadjuvant therapy, or will proceed with surgery and adjuvant treatment. Appointing a longer-term quarterback function at diagnosis may also be premature, as treatment decisions inform the quarterback assignment, e.g., medical oncology for neoadjuvant cases, or surgery for “surgery-first” patients.

To assist the newly diagnosed patient in orchestrating the initial consultations and reaching the point of these decisions, we propose that an interim care project plan - Care Initiation Sequence - be created at that time. It will serve as the basis for initial patient and care team engagement and will be replaced by a longer-term Care Sequence when necessary workup is completed and key treatment decisions are reached. Radiology is well-positioned to assume an initial quarterback function, constructing the Care Initiation Sequence and engaging the care team. This role may then be transitioned to another domain, when the longer-term Care Sequence is created. In this setting, the radiologist assumes the quarterback physician function making the initial clinical determinations and recommendations. Based on these recommendations, a nurse constructs the Care Initiation Sequence and works with the patient and other providers to organize this care. In organizations where a breast cancer nurse navigator role exists, the nurse may construct the Care Initiation Sequence and help the patient follow it.

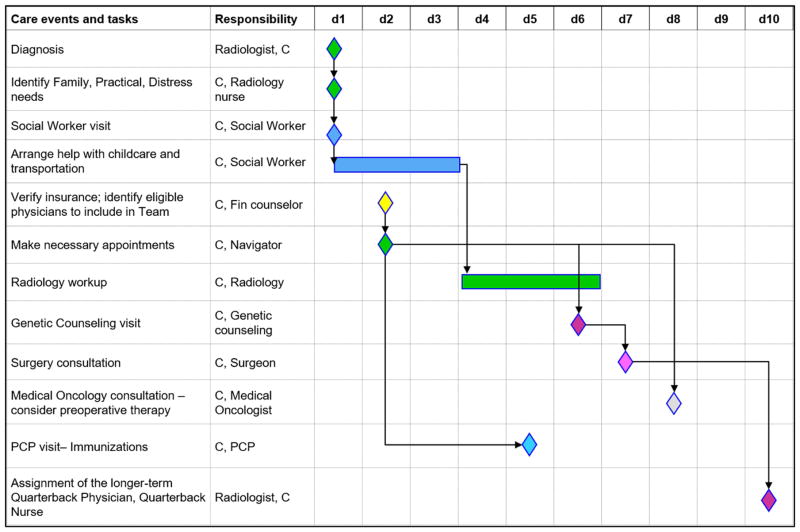

Figure 3 provides an example of a Care Initiation Sequence for a hypothetical Patient C at breast cancer diagnosis. The sequence uses a Gantt chart format, to manage the care as a project, including the sequence of care (diamonds/rectangles) and dependencies (lines/arrows). Gantt charts are widely used in project management to graphically depict and manage project task schedule, responsibilities, task dependencies and desired sequence of events across team members. This makes a Gantt chart a useful tool to visually represent and coordinate breast cancer care planning, which requires management of care interdependencies and sequences across a diverse group of care team members.

Figure 3. Case of Patient C. Example of Care Initiation Sequence.

d1–d10, days, beginning with diagnosis

C- The patient

PCP – Primary Care Physician

A Bar represents treatment / care; a Diamond represents a visit / decision.

Responsibility would be filled in with specific names of providers

For illustrative purposes, C combines the needs of Patients A and B described earlier. C is indicated for genetic counseling and may be a candidate for neoadjuvant therapy. C has childcare needs that may challenge her ability to obtain timely consultations. The radiology quarterback function (radiologist / nurse tandem) identifies the scope of initial consultations and care, determines C’s practical needs and develops the Care Initiation Sequence, incorporating patient preferences where relevant. The Sequence specifies the timing, order and responsibilities for key events, including patient’s tasks and responsibilities, e.g. making specialist appointments. The sequence guides the resolution of C’s childcare needs in time for her projected specialist visits. The geneticist and medical oncologist referrals and appointments are planned early to avoid the pitfalls of Cases A and B and allow timely origination of neoadjuvant therapy and/or genetic testing, if recommended for the patient. The care initiation period, while the patient is in the “waiting” mode, also offers an opportunity to plan other care, recommended before cancer treatment, e.g. immunizations (Figure 3). The quarterback function engages the initial care team, provides them the Sequence and informs of the time sensitivity of appointments and respective decisions.

This approach and process cannot be performed ad-hoc, and the Care Initiation Sequences cannot be created from scratch for individual patients. A concerted, systematic institutional implementation of this approach is necessary,23 including: (1) developing Care Initiation Sequence templates for typical patient subgroups, which could be personalized for individual patients, (2) establishing institutional criteria that radiology uses to personalize Care Initiation Sequences, e.g., for referral to genetics or to oncologist for neoadjuvant therapy consideration; (3) streamlining internal processes of relevant specialties, e.g., expedited geneticist appointment and testing for newly diagnosed, versus high risk patients. Participation and buy-in from institutional leadership and relevant specialties is necessary for successful implementation. We are currently piloting the 4R approach for breast cancer patients at academic, community and safety settings, and expect that our results and experience will inform broader adoption of the 4R approach at care initiation and during treatment.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RADIOLOGY

The application of the 4R approach at care initiation takes radiology into the territory that may be unfamiliar to many in this specialty. However, it emerges from the role radiology currently plays in cancer care for a number of cancers, as an entry point for diagnosed patients into the care system. Some radiologists already deliver breast cancer diagnosis to patients, advise them regarding the next steps and even navigate them to their next steps in care. The 4R approach will allow them to provide this service in a more systematic, comprehensive and patient-centric manner. It is aligned with the call to rethink patient experience by applying “revolutionary and innovative ideas” and considering practices of other industries.50 The 4R approach uses the concepts of Project Management, broadly employed in other industries, and applies them to cancer care initiation and delivery.

The 4R approach to breast cancer care initiation supports the ACR vision for radiology, including expansion of value-added services, such as care coordination, participating in multi-disciplinary teamwork, and improving patient engagement.2,3 Assuming the Quarterback role for cancer care initiation sets up radiology as a value-adding team member, and integrates it more seamlessly into the care team throughout cancer care continuum and during survivorship.

However, the implementation of 4R at cancer care initiation is far from trivial and will require substantial efforts. First, the radiology practice model must change to enable the role of cancer care initiator and care team member. The model should incorporate direct interaction with patients necessary to discuss the diagnosis and the Care Initiation Sequence, including identification of relevant patient preferences (e.g., interest in genetic assessment, if indicated), developing the Care Initiation Sequence and explaining the included referrals. This will require developing trusted relationships with them, which is important both to develop the Care Initiation Sequence, and to support the ongoing role of radiology during cancer treatment and survivorship. The radiology practice model should also incorporate the time and process for interactions with other specialties during initial care team engagement and ongoing teamwork.

Second, the 4R components must be developed, as described earlier in this article. This may necessitate efforts at two levels, and radiologists are key to both. Developing Care Initiation Sequence templates, criteria for initial referrals to specialists and framing of the Quarterback and other team roles requires a collaboration of multiple specialties, and input from relevant medical societies, including ACR and other radiology bodies. The implementation of 4R in practice entails adaptation of the templates and 4R components to the local and institutional practices, settings and patient populations. Radiologists at specific care institutions are central to this effort and may champion it, demonstrating thought and organizational leadership.

Third, radiology training, e.g. breast imaging fellowships, should include development of the skillsets that enable radiology’s role in the 4R approach in cancer care. Training should include the clinical background necessary for providing referrals to other specialties, competence for patient interaction and engagement, and systematic teamwork skillset.

While these efforts are considerable and extensive, they match the ambition, aspiration and vision of radiology in the evolving healthcare environment. The proposed model may not be applicable to all care settings and populations, but it could be an important addition to radiology’s array of services.

In conclusion, radiology seeks to transform itself under the Triple Aim of health reform and improve patient experience and engagement. We propose implementing the 4R approach at breast cancer diagnosis, with radiology quarterbacking care initiation, and care team and patient engagement in a systematic, coordinated fashion. This model, and respective role of radiology, provides opportunities for value-added services and solidifying radiology’s relevance in the evolving healthcare paradigm. Three efforts will be necessary to implement 4R at care initiation: changing the radiology practice model to incorporate patient interaction and teamwork, developing the 4R content and local adaption approaches, and enriching radiology training with relevant clinical knowledge, patient interaction competence and teamwork skillset.

Take-Home Points.

Post-diagnosis initiation of breast cancer care provides radiology with an opportunity to expand its value-added services and increase patient and care team engagement. Breast cancer care initiation is complex and requires orchestrating multiple care events across specialties in a short time.

The 4R Model (Right Information and Right Care for the Right Patient at the Right Time) may serve as the mechanism for this engagement and value-added service delivery. The 4R approach uses Project Management to create Care Sequences for patients and care teams, in order to manage timing and sequencing of interdependent care events across specialties.

Applying the 4R approach at breast cancer initiation, radiology can play the Quarterback role for the patient and the care team, and organize initial patient care by using a Care Initiation Sequence, as the patient care “project plan.”

To implement 4R at cancer care initiation, it will be necessary to: incorporate patient interaction and teamwork into the radiology practice model; develop the 4R content and local adaption approaches; and enrich radiology training with relevant clinical knowledge, patient interaction competence and teamwork skillset.

Radiology departments may start implementing 4R at care initiation by developing Care Initiation Sequence templates for typical patient subgroups, establishing institutional criteria for personalizing Care Initiation Sequences from templates and working with other specialties to streamline relevant care processes.

Radiology’s role at breast cancer care initiation may serve as a model for other cancers in which radiology serves as the entry point for newly diagnosed patients into the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

Research support

The work of Christine Weldon and Julia Trosman was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (UG1CA189828), a grant from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) / Pfizer (22896331), a grant from the J.B. & M.K. Pritzker Family Foundation and a grant from the Lynn Sage Cancer Research Foundation. The work of Swati Kulkarni was supported by James Ewing Foundation of the Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Investigator Award in Breast Cancer Research, Funded by Susan G. Komen for the Cure. The work of Melissa Simon was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (UG1CA189828), grants from the National Institutes of Health (U54 CA203000, CA2022995, CA2022997; R01CA163830), a grant from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) / Pfizer (22896331), a grant from the J.B. & M.K. Pritzker Family Foundation and a grant from the Lynn Sage Cancer Research Foundation. The work of Ruth Carlos was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (UG1CA189828).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Christine Weldon and Julia Trosman report that they received funding from Foundation Medicine and Genentech. Swati Kulkarni reports that she received funding from Pfizer, Inc. Ruth Carlos reports that she is deputy editor of the Journal of the American College of Radiology. Art Small and Mikele Bunce report that they are employees and shareholders of Genentech/Roche. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen B., Jr Improving our patients’ experience in their radiological care. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:767–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayo RC, 3rd, Parikh JR. Breast Imaging: The Face of Imaging 3.0. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swan JS, Pandharipande PV, Salazar GM. Developing a Patient-Centered Radiology Process Model. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:510–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhor CM, Mercado CL. Integrating Customer Intimacy Into Radiology to Improve the Patient Perspective: The Case of Breast Cancer Screening. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:265–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itri JN. Patient-centered Radiology. Radiographics. 2015;35:1835–46. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruman JC. An accidental tourist finds her way in the dangerous land of serious illness. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:427–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruman J. Preparing patients to care for themselves. Am J Nurs. 2014;114:11. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000451657.77642.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okun S, Schoenbaum SC, Andrews D, et al. Patients and Health Care Teams Forging Effective Partnerships. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dentzer S. Rx for the ‘blockbuster drug’ of patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:202. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:223–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berwick DM. What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w555–65. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner EH. Effective teamwork and quality of care. Med Care. 2004;42:1037–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000145875.60036.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phelan EA, Balderson B, Levine M, et al. Delivering effective primary care to older adults: a randomized, controlled trial of the senior resource team at group health cooperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1748–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bickell NA, LePar F, Wang JJ, et al. Lost opportunities: physicians’ reasons and disparities in breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2516–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bickell NA, Mendez J, Guth AA. The quality of early-stage breast cancer treatment: what can we do to improve? Surgical oncology clinics of North America. 2005;14:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonzee NJ, Ragas DM, Ha Luu T, et al. Delays in Cancer Care Among Low-Income Minorities Despite Access. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:506–14. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, et al. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care:: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balogh EP, Ganz PA, Murphy SB, et al. Patient-centered cancer treatment planning: improving the quality of oncology care. Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. The oncologist. 2011;16:1800–1805. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosty MP, Bruinooge SS, Cox JV. Intentional approach to team-based oncology care: evidence-based teamwork to improve collaboration and patient engagement. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:247–8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.005058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taplin SH, Weaver S, Salas E, et al. Reviewing cancer care team effectiveness. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:239–46. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taplin SH, Weaver S, Chollette V, et al. Teams and teamwork during a cancer diagnosis: interdependency within and between teams. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:231–8. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trosman JR, Carlos CR, Simon MA, Madden DL, Gradishar WJ, Benson AB, 3rd, et al. Care for a Patient With Cancer As a Project: Management of Complex Task Interdependence in Cancer Care Delivery. J Oncol Pract. 2016 Aug 30; doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.013573. pii: JOPR013573. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patlak M, Balogh E, Nass SJ. Patient-Centered Cancer Treatment Planning. 2011 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landercasper J, Linebarger JH, Ellis RL, et al. A quality review of the timeliness of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in an integrated breast center. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:449–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loftus L, Laronga C, Coyne K, et al. Race of the clock: reducing delay to curative breast cancer surgery. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(Suppl 1):S13–5. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, Shepard JA, et al. Timeliness of Recommended Follow-Up After an Abnormal Finding on Diagnostic Chest CT in Smokers at High Risk of Developing Lung Cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks MA, Mathieu JE, Zaccaro SJ. A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of management review. 2001;26:356–376. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brannick MT, Roach RM, Salas E. Understanding team performance: A multimethod study. Human Performance. 1993;6:287–308. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weldon CB, Trosman J, Schink JC. Cost of cancer: there is more to it than containing chemotherapy costs. Oncology (Williston Park) 2012;26:1116, 1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinberg DB, Cooney-Miner D, Perloff JN, et al. Building collaborative capacity: promoting interdisciplinary teamwork in the absence of formal teams. Med Care. 2011;49:716–23. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215da3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire WL. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:263–300. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weldon CB, Trosman JR, Gradishar WJ, et al. Barriers to the use of personalized medicine in breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e24–31. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: the Patient Navigation Research Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guzzo RA, Shea GP. Group performance and intergroup relations in organizations. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. 1992;3:269–313. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wageman R, Gardner H, Mortensen M. The changing ecology of teams: New directions for teams research. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2012;33:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salas E, Rosen MA, Burke CS, et al. The wisdom of collectives in organizations: An update of the teamwork competencies. Team effectiveness in complex organizations. cross-disciplinary perspectives and approaches. 2009:39–79. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trosman JR, Weldon CB. Models of Care Delivery. In: Al Benson III, MD, Chakravarthy A MD, Hamilton Stanley MD, editors. Cancers of the Colon and Rectum. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Management Series. Chapter 17. 2014. p. 288. Hardback. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wageman R. How leaders foster self-managing team effectiveness: Design choices versus hands-on coaching. Organization Science. 2001;12:559–577. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bickell NA, Neuman J, Fei K, et al. Quality of breast cancer care: perception versus practice. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1791–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taplin SH, Yabroff KR, Zapka J. A multilevel research perspective on cancer care delivery: the example of follow-up to an abnormal mammogram. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1709–15. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fanjiang G, Grossman JH, Compton WD, et al. Building a Better Delivery System:: A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership. National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nokes S, Kelly S. The definitive guide to project management: the fast track to getting the job done on time and on budget. Pearson Education; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dinsmore PC, Cooke-Davies TJ. Right projects done right: from business strategy to successful project Implementation. John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harvard Business Review. 2013. HBR Guide to Project Management (HBR Guide Series) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinn T. Bringing A Management Model To Healthcare: Team-Based Care. [Accessed 11/10/2015];Forbes. 2014 http://www.forbes.com/sites/groupthink/2014/12/09/bringing-a-management-model-to-healthcare-team-based-care/

- 48.Scher DL. 5 lessons healthcare can learn from project management. [Accessed 11/10/2015];Medical practice insider. http://www.medicalpracticeinsider.com/blog/business/5-lessons-healthcare-can-learn-project-management.

- 49.Bosch M, Faber MJ, Cruijsberg J, et al. Review article: Effectiveness of patient care teams and the role of clinical expertise and coordination: a literature review. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66:5S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1077558709343295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raman SP, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Introduction to rethinking the patient experience. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Brogan B, et al. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 counseling and testing on newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1823–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weitzel JN, McCaffrey SM, Nedelcu R, et al. Effect of genetic cancer risk assessment on surgical decisions at breast cancer diagnosis. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1323–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1323. discussion 1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rehman S, Crane A, Din R, et al. Understanding avoidance, refusal, and abandonment of chemotherapy before and after cystectomy for bladder cancer. Urology. 2013;82:1370–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holmes D, Colfry A, Czerniecki B, et al. Performance and Practice Guideline for the Use of Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy in the Management of Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3184–90. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson RH, Kroon L. Optimizing fertility preservation practices for adolescent and young adult cancer patients. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:71–7. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in America, 2014: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:119–42. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Margalit DN, Losi SM, Tishler RB, et al. Ensuring head and neck oncology patients receive recommended pretreatment dental evaluations. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:151–4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bunnell CA, Losk K, Kadish S, et al. Measuring opportunities to improve timeliness of breast cancer care at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(Suppl 1):S5–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lazenby M, Ercolano E, Grant M, et al. Supporting commission on cancer-mandated psychosocial distress screening with implementation strategies. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e413–20. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trosman JR, Weldon CB, Dupuy D, et al. Why do breast cancer programs fail to refer patients to genetic counseling upon obtaining family history? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge: PMBOK(R) Guide 5th Edition. Project Management Institute, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shenhar AJ, Dvir D. Reinventing project management: the diamond approach to successful growth and innovation. Harvard Business Review Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luecke R. Managing projects large and small: the fundamental skills for delivering on budget and on time. Harvard Business Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]