Abstract

Mental illnesses are common worldwide, and nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness have an impact on the care they deliver. This integrative literature review focused on nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness. Four databases were searched between January 1, 1995 to October 31, 2015 selecting studies, which met the following inclusion criteria: 1) English language; and 2) Research in which the measured outcome was nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness. Fifteen studies conducted across 20 countries that 4,282 participants met the inclusion criteria. No study was conducted in the United States (U.S.). Studies reported that nurses had mixed attitudes toward mental illness, which were comparable to those of the general public. More negative attitudes were directed toward persons with schizophrenia. Results indicate the need for further research to determine whether attitudes among nurses in the U.S. differ from those reported from other countries and to examine potential gaps in nursing curriculum regarding mental illness.

Mental illnesses are common worldwide and represent the fifth leading disorder globally (Whiteford et al., 2013). About 450 million people suffer from mental illnesses worldwide (World Health Organization, 2001). In the United States (U.S.) alone, over 43.7 million of adults, 18.6% of all the population, have a mental illness diagnosis (National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2013). Effective treatments exist, but only 39% of people with diagnosed mental illness receive treatment and among those who receive treatment, one in five terminate treatment prematurely (NIMH, 2001, Olfson et al., 2009).

Various factors play a role in decision-making as it pertains to seeking help for mental illness. Those factors include financial concerns, poor self-perception, limited access and stigma (Mojtabai et al., 2011). Goffman (1963) defines social stigma as an attribute that is discredited by society. Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013, suggested in a recent review that stigma related to mental illness causes health inequalities by preventing people from seeking help that they need. People with depression are more likely to suffer from physical health comorbidities and are reported to be twice as likely as non-depressed patients to have two or more physical illnesses (Smith et al., 2014). According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), anxiety disorders cost the U.S. more than $42 billion per year, representing almost a third of total mental health spending (ADAA, 2010). People who suffer from anxiety disorders are three to five times more likely to visit primary care and gastroenterology than people without the disorder, resulting in increased health care costs (Hoffman, Dukes, & Wittchen, 2008).

Delaying treatment for mental illness may result in negative consequences. The longer the duration of untreated illness, the worse the outcomes in psychosis, mood disorders and anxiety disorders (Dell’osso, Glick, Baldwin, & Altamura, 2012). Furthermore, after initiation of treatment, non-adherence and drop out rates may result in unfavorable outcomes (Barrett et al., 2008).

A negative patient-provider relationship, or personal and professional characteristics of the providers, may compel the patient to leave treatment (Reneses, Munoz, & Lopez-Ibor, 2009). Hoge et al., (2014) performed a study at a U.S. Veterans Administration Hospital and reported that dissatisfaction with the provider was one of the reasons for patients to drop out of treatment. Furthermore, in a recent integrative review, Newman, D., O’Reilly, P., Lee, S. H., & Kennedy, C. (2015) underlined the importance of relationships between the providers, such as nurses, and the patients who were seeking help for mental health problems. In addition to the patient-provider relationship, the impact of provider stigma is emerging in the literature, and has been identified as the strongest barrier toward help seeking behavior of individuals with mental illness (Clement et al., 2015, Corrigan, 2004; Evans-Lacko, Brohan, Mojtabai, & Thornicroft, 2012; Hinshaw & Stier, 2008; Kim, Britt, Klocko, Riviere, & Adler, 2011). Newman et al., (2015) re-iterated the importance of stigma, affirming that negative nursing attitudes toward mental illness have a profound impact on the delivery of care. Similarly, McDonald et al. (2003) confirm that the nurses’ care of patients is negatively impacted if the patient has a mental illness. The investigators presented vignettes that represented three patients admitted to the emergency room with a possible myocardial infarction. 1) The patient was taking an antipsychotic medication; 2) The patient was taking alprazolam (Xanax), a medication used to treat anxiety disorder; and 3) The patient had no history of psychiatric treatment (control). A significant difference in symptom recognition was found. Only 31% of nurses who read the first vignette identified a possibility of myocardial infarction in a patient taking antipsychotic medications compared to 51% of nurses in the control group. Additionally, when patients were experiencing increased anxiety, 78.9% of nurses in the control group stated that they could be having a heart attack versus 45.5% only in the psychotic patient group. This study highlights a general tendency of nurses to stereotype patients with mental illness thereby responding differently to them (McDonald et al., 2003). Corrigan et al., (2014) found that providers’ attitudes were different toward patients with a diagnosis of mental illness than toward those without.

Although the factors that influence attitudes regarding mental illness have been studied for many years (Ajzen, 2005; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein, 2010; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Fishbein, Ajzen, Albarracin, & Hornik, 2007), to our knowledge, there has been no integrative literature review exploring nursing attitudes toward patients with mental illness. Obtaining a clear understanding of nursing attitudes may, inform policy and be used to implement change to ensure optimal patient care.

Aim

The aim of this integrative review is to explore nurses’ attitudes toward patients with mental illness.

Methodology

Defining Mental Illness

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) defines mental illness as “disorders generally characterized by dysregulation of mood, thought, and/or behavior, as recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition, of the American Psychiatric Association.” People with mental illness have impaired thinking, and their feelings may affect their ability to function on a daily basis. For the purpose of this review, we used the terms mental illness, mental disorders, and psychological problems interchangeably, which included, but not limited to, mood and psychotic disorders, as well as anxiety. Given the change in mental illness criteria introduced by DSM IV in 1994, only studies that used DSM IV and DSM V were included (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, 2013).

Literature Search

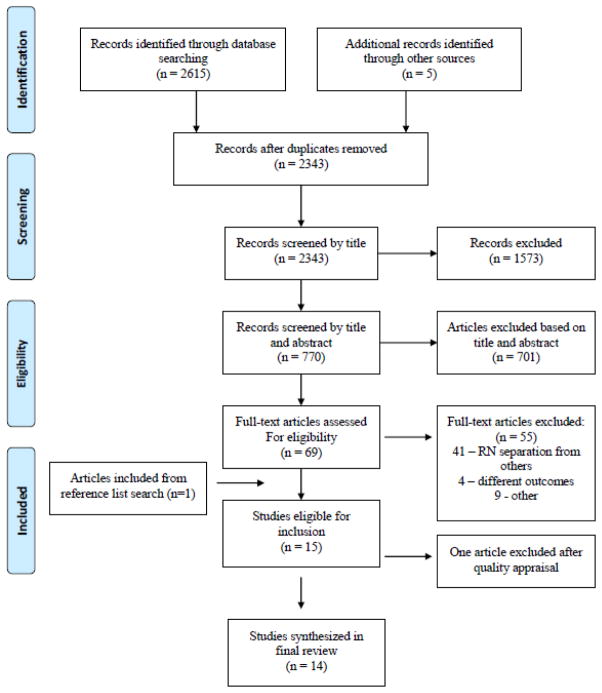

The conduct of this integrative review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, & Mulrow, 2009). We searched the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed in September, 2015. The following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were searched: (‘mental illness’ OR ‘mental health’) AND (‘nurses’ OR ‘nurs*’) AND (‘stereotyp*’ OR ‘stigma’ OR ‘prejudice’ OR ‘discrimination’ OR ‘attitudes” OR ‘beliefs’).

Data were initially extracted from the four databases by the first author who screened all articles’ titles and abstracts. Two authors independently assessed selected full text articles for eligibility, and the discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The inclusion criteria were studies published between January 1, 1995 and October 31, 2015 in English and included nurses as participants in which the measured outcome was nursing attitudes toward mental health and/or illness in patients. Personal accounts, editorials, and/or single case studies, studies not written in English, and studies that explored attitudes of other professionals were excluded.

Quality Appraisal

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (QATOCCS) from the National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The QATOCCS was modified to fit the needs of cross-sectional studies, as many questions were relevant to cohort studies only. Two researchers appraised the quality of the studies and 100% consensus of each study’s quality was achieved. Studies were rated in tertiles: low quality (0 – 33%), moderate quality (34 – 66%), and high quality (67 – 100%).

Results

The initial database search yielded 2,615 articles, and 2,343 remained after duplicates were removed. Following title screening, 770 papers were identified as potentially eligible and 701 articles were excluded after title and abstract review, leaving 69 articles for full text screening. Fourteen articles met the inclusion criteria. A search of the reference lists of the 14 final articles yielded an additional five articles eligible for inclusion in the study. A full text review by two researchers was performed again and one of the five articles was included in the final review yielding 15 studies that met initial eligibility criteria.

Quality Appraisal

Two researchers reached consensus on the quality of each study. Twelve studies were determined to be of high quality (Arvaniti et al., 2009; Chambers et al., 2010; Foster et al., 2008; Hamdan-Mansour & Wardam, 2009; Hsiao et al., 2015; Linden & Kavanagh, 2012; Magliano et al., 2004; Munro & Baker, 2007; Nordt, 2006; Scheerder et al., 2011; Serafini et al., 2011; Sevigny et al., 1999). One study score within the moderate quality range (Kukulu & Ergun, 2007). Two studies received lower quality scores because some key methodological elements were not reported, including sampling, sample recruitment and size, and lack of information about study measures. One of these lacked sufficient methodological rigor to be included, leaving 14 studies remaining in the final synthesis of the review. A PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

The studies were conducted across 20 countries. None of the studies were performed in the U.S. Eight of the studies were conducted in Europe (two of which included more than one country), four in Asia, and three in the Middle East. Of the 14 studies, six focused on attitudes toward schizophrenia and/or depression, while the remaining nine concentrated on mental illness in general. All of the studies had a cross-sectional design. Twelve studies included mental health nurses who worked with mentally ill inpatients or outpatients. Aydin, Yigit, Inandi, & Kirpinar, (2003) conducted a study in an outpatient, non-psychiatric setting. Arvaniti et al., (2009) and Scheerder et al., (2010) performed their studies on medical rather than psychiatric units. Study characteristics and key findings are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study | Country | Sample | Measures | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arvaniti et al., 2009 | Greece | 130 nurses 76 physicians 140 other staff 239 medical students 10 medical wards and one psychiatric ward of a general hospital |

|

(% Nurse Agreement) Social discrimination

Social restriction:

Social integration:

|

| Aydin et al., 2003 | Turkey | 40 nurses 40 academicians 40 physicians 40 hospital employees Medical clinics |

|

|

| Chambers et al., 2010 | Finland Italy Lithuania Portugal Ireland |

810 nurses Psychiatric Hospitals (n=21) |

|

|

| Foster et al., 2008 | Fiji | 23 nurses 48 orderlies Psychiatric hospital |

|

Etiology(% agreement)

Attitudes “Psychiatric illness deserves as much attention as physical illness” (86.9%)

|

| Hamdan-Mansour and Wardam., 2009 | Jordan | 92 nurses Acute and chronic mental health inpatient and outpatient facilities |

|

Nurse Agreement (%)

|

| Hsiao et al., 2015 | Taiwan | 180 nurses. Psychiatric hospitals (n=3) |

|

|

| Kukulu and Ergun, 2007 | Turkey | 543 nurses Psychiatric wards of teaching hospitals |

|

Etiology(% Agreement)

Social distance

|

| Linden and Kavanagh 2012 | Ireland | 121 nurses 66 student mental health nurses Inpatient and Community Setting (n=2) |

|

CAMI

SIS

|

| Magliano et al., 2004 | Italy | 190 nurses 110 psychiatrists 709 patient relatives Mental health services (n=30) |

|

Etiology of schizophrenia (% Nurse agreement) Heredity (74%); Stress (53%); Alcohol (42%), Drugs (48%); Family conflict (48%), Trauma (36%) Social functioning

Civil rights

|

| Munro and Baker 2007 | England | 141 nurses Acute mental health unit |

|

Positive Attitudes (% Nurse Agreement)

Negative Attitudes

Neutral Attitudes

|

| Nordt et al., 2006 | Switzerland | 684 nurses 204 psychiatrists 185 other professionals Psychiatric wards of hospitals (n=29) Outpatient clinics (n=3) 1737 members of the general public |

|

Social restrictiveness (% Nurse Agreement)

|

| Scheerder et al., 2011 |

European Alliance Against Depression Belgium Estonia France Germany Hungary Ireland Italy Scotland Slovenia |

887 nurses 334 nursing assistants 169 mental health professionals (physicians and mental health professionals) 968 community facilitators (clergy, social workers) from a training program and professional associations |

Adaptation of 3 tools

|

Positive Attitudes toward mental health (% agreement)

Negative attitudes toward treatment (% agreement)

Etiology of mental illness

|

| Serafini et al., 2011 | Italy | 50 nurses 50 medical physicians 50 medical students 52 psychiatric outpatients from a university hospital |

|

Vignettes (% Nurse Agreement) Positive attitudes

Negative attitudes

Neutral attitudes

SSQ Significant response difference between medical doctors and nurses (p.038) |

| Sevigny et al., 1999 | China | 74 nurses 26 physicians Psychiatric hospital |

|

Nurses endorsed mostly negative attitudes(% Nurse Agreement)

Nurses endorsed more negative attitudes than physicians |

Study Measures

Numerous measures were utilized across countries. Three studies used the Attitudes Toward Acute Mental Illness Scale (ATAMH33) (Baker, Richards, & Campbell, 2005) and four studies used Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness (CAMI) (Taylor, Dear, & Hall, 1979; Taylor & Dear, 1981). The following measures were in at least one study: The Level of Contact Report (Holmes, Corrigan, Williams, & Canar, 1999), the Opinion about Mental Illness (Madianos, Madianou, Vlachonikolis, & Stefanis, 1987), the Authoritarianism Scale (Adorno, 1950), Social Distance (Arkar, 1991), Burden of Illness (Eker & Arkar, 1991), Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health Profession version (Hojat, Gonnella, Nasca, Mangione, & et al., 2002), Attitudes of Mental Illness Questionnaire (Luty, Fekadu, Umoh, & Gallagher, 2006), Social Interaction Scale (Kelly, St Lawrence, Smith, & Hood, 1987), Social Acceptance Scale (Angermeyer & Matschinger, 1997), and Standardized Stigma Questionnaire (Haghighat, 2005). Kukulu and Ergun, (2007) utilized an adaptation of multiple instruments, but the researchers were unable to assess its validity because the instruments’ descriptions and psychometric testing were only being available in studies published in the Turkish language.

Findings

In these studies, attitudes toward mental illness were compared between psychiatric nurses and nurses working in non-psychiatric settings as well as between nurses and the general public. Finally as discussed below, four common themes emerged: 1) etiology of mental illness; 2) social restrictiveness and distance; 3) perceived dangerousness; 4) attitudes specific to schizophrenia and depression.

Attitudes of psychiatric nurses compared to nurses working in other settings

Nursing attitudes were examined first by comparing nurses that were working on psychiatric wards compared to non-psychiatric nurses working on a medical ward or outpatient clinics. However, no study compared directly psychiatric versus non-psychiatric nurses. Authors of three studies reported the attitudes of non-psychiatric nurses (Arvantini et al., 2009; Aydin et al., 2003; Scheerder et al., 2010). Arvantini et al., (2009) reported both positive and negative nursing attitudes toward mental illness. For example, 60.7% of nurses in this study agreed that mentally ill patients should be separated from patients without mental illness. On the contrary, 76% of psychiatric and non-psychiatric nurses in this study viewed mentally ill patients as not being dangerous. Aydin et al., (2003) reported that nurses endorsed social discrimination more than the doctors and showed low support for social integration. They also endorsed social restriction more than other professionals, such as doctors and medical students. However, nurses endorsed social care questions at a higher level than other groups. Negative nursing attitudes toward patients with schizophrenia and depression were also reported. This finding was consistent among studies that examined both psychiatric and non-psychiatric nurses.

Scheerder et al. (2010) found that non-psychiatric nurses held mostly positive attitudes toward people with depression. Sixty percent of nurses considered depression as an illness and 81.9% of respondents agreed (n=1533) that depression was treatable. However, nurses’ attitudes were less positive compared to other mental health professionals, such as clinical social workers, psychologists, and counselors, which can be explained by lack of specialty training among nurses as compared to professionals in mental health.

There was a variability of psychiatric nurses attitudes across studies. Three studies reported positive attitudes (Chambers et al., 2010; Linden & Kavanagh, 2012; Munro & Baker, 2007) and four studies exemplified negative attitudes (Hamdan-Mansour & Wardam, 2009; Hsiao et al., 2015; Magliano et al., 2004; Sevigny et al., 1999). The remaining studies were a combination of both positive and negative (Foster et al., 2008; Kukulu & Ergun, 2007; Nordt et al., 2006; Serafini et al., 2011).

In a large European study, Chambers et al. (2010) assessed attitudes of 810 mental health nurses and reported that respondents rejected authoritarian attitudes as well as the desire for social distance toward people with mental illness and not only displayed benevolent attitudes, but also endorsed community integration. Linden and Kavanagh (2011) reported similar results. Munro and Baker (2007) reported that their respondents mostly agreed with positive statements, such as “psychiatric illness deserves at least as much attention as physical illness” (95.7% agreement) and disagreed with negative statements, such as “depression occurs in people with weak personality” (90% disagreed). It is important to mention, that even in studies that reported mostly positive attitudes, there were some negative attitudes, such as consideration that psychiatric drugs were used to control disruptive behavior (61.7% agreement), and that nurses perceived mentally ill patients with pessimism (semantic differential: pessimism – optimism).

Authors of four studies reported that psychiatric nurses had mostly negative attitudes (Hamdan-Mansour & Wardam, 2009; Hsiao et al., 2015; Magliano et al., 2004; Sevigny et al, 1999). Majority of nurse respondents considered that psychiatric illness did not deserve as much attention as physical illness (94.6%, 87/92), 84.8% (78/92) considered that a person with mental illness had no control over her or his emotions, and 68.5% (63/92) agreed that depression was occurring in people with weak personality (Hamdan-Mansour & Wardam, 2009). Hsiao et al., (2015) found that psychiatric nurses had significantly more negative attitudes toward patients with schizophrenia than nurses who worked in community-based clinics, and that nurses had more negative attitudes toward people with schizophrenia than those with depression. Magliano et al., (2004) reported that 86% (163/190) of nurses considered people with schizophrenia as unpredictable, and 87% (165/190) considered that people were keeping away from patients with schizophrenia. Nurses also agreed that patients with schizophrenia should not have children (72%, 137/190), and that they should not get married (63%, 119/190), (Magliano et al., 2004). Even though most responses were negative, nurses also agreed with positive statements and considered that patients with schizophrenia should be allowed to vote (63%, 119/190), and that they were as able to work as other people (79%, 150/190), (Magliano et al., 2004). Sevigny et al., (1999) reported that nurses mostly held negative attitudes toward mentally ill people and generally more negative than physicians. Thirty eight percent of nurses considered a mental illness as any other illness (n=74) and 63% displayed authoritarian attitudes toward mentally ill patients. Nurses in Sevigny et al., (1999) also reported positive attitudes. Almost 60% of respondents disagreed that lack of discipline and will power was causing mental illness.

Four studies reported mixed attitudes (Foster et al., 2008; Kukulu et al., 2007; Serafini et al., 2011; Nordt et al., 2006). The authors of all four studies reported results that showed negative and positive attitudes toward mental illness. Nordt et al., (2006) reported that nurses endorsed negative stereotypes of mentally ill people, but opposed restriction of civil rights of the mentally ill. Serafini et al., (2011) reported that while 75% of nurses believed that people with schizophrenia were unpredictable and 80% expressed a desire for social distance, 60% did not believe that people with schizophrenia were dangerous (n=50). Kukulu and Ergun, (2007) also confirmed the desire for social distance: while 56.7% of nurses said that they could work with a person with schizophrenia, 91.7% would not marry a person with that disorder (n=543). Foster et al., (2008) also reported mixed attitudes among their respondents: while 91.3% of nurses considered that people with a psychiatric history should be given jobs with responsibilities, 91.3% said that psychiatric medications were used to control disruptive behavior instead of being used to control the symptoms (n=23).

Attitudes of nurses compared to the general public

Three studies compared nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness with non-healthcare professionals such as family members and the general public, with mixed results (Magliano et al., 2004; Nordt et al., 2006; Scheerder et al., 2011). Magliano et al. (2004) reported that nurses (n=190) had more negative attitudes than the relatives (n= 709) of patients with mental illness. For example, 86% of nurses believed that patients with schizophrenia were unpredictable compared with only 65% of relatives having the same attitude. In addition, 72% of nurses compared to 32% of relatives considered that mentally ill patients should be punished for wrong behavior in the same manner as other people. In regards to personal civil rights, nurses and relatives had similar attitudes about whether those with schizophrenia should have children (29%) or have the right to vote (66%). Finally, while almost half of the relatives (44%) considered that mentally ill people could work as other people, 79% of nurses disagreed.

In a second study, Nordt et al., (2006) compared five groups, including nurses and 253 members of the general population. The nurses and the general population agreed with negative stereotypes of the mentally ill at a similar level. However, while 54% of nurses opposed revocation of the Driver’s License, 65.7% of the general public endorsed that restriction. More members of the general public than nurses considered that the mentally ill people should not vote (19.6% vs. 2.8%), and while almost all nurses agreed to compulsory admission (98.2%), 67.5% of general public respondents endorsed this option.

In the third study (Scheerder et al., 2010), community facilitators (clergy, police, youth workers, pharmacists, social workers and volunteers) were asked their opinions about depression and were compared with mental health professionals and nurses. While 77% of community facilitators considered that depression is a real disease, 60% of nurses endorsed that opinion. Both groups agreed that depression could be treated (83.4% of community facilitators vs. 81.9% of nurses).

Specific themes

Etiology of mental illness

Seven studies reported nurses’ beliefs about the etiology of mental illness (Foster et al., 2008; Kukulu & Ergun, 2007; Magliano et al., 2004; Munro & Baker, 2007; Scheerder et al., 2011; Serafini et al., 2011; Sevigny et al, 1999). Nurses predominantly have the attitude that mental illness is a disease of a hereditary nature (range: 65%–93%). Additional attitudes about the etiology of mental illness included personal weakness, result of alcohol and/or drug use, and stress and family conflict. Most nurse respondents (59–90%) did not consider mental illness as emanating from a lack of will power (Munro & Baker, 2007; Sevigny et al., 1999).

Social restrictiveness and distance

Social restrictiveness in mental illness stigma literature measured the desire to restrict people with mental illness from roles in society. Social distance refers to the proximity that one desires between self and a mentally ill person in a social situation. Nine studies reported nurses’ attitudes toward social restrictions that should be imposed on the mentally ill as well as the social distance that the respondents preferred to maintain from this population (Arvaniti et al., 2009; Aydin et al., 2003; Chambers et al., 2010; Kukulu et al., 2007; Linden & Kavanagh, 2012; Magliano et al., 2004; Munro & Baker, 2007; Nordt et al., 2006; Sevigny et al., 2011. Attitudes toward social restrictions and distance were measured through questions that examined attitudes toward right to vote, revocation of one’s driver’s license, isolation of the mentally ill from the residential neighborhoods, mandatory abortion for women with diagnosed schizophrenia, and opposition to marrying people with mental disorders. Almost half of the nurses (46%, 311/676) in one study agreed that people who suffered from any mental health issues should have their driver’s license revoked (Nordt et al., 2006). The majority of respondents would oppose a marriage of a family member to a person with mental illness. Almost two-thirds (63%) of nurses in one study agreed that patients with schizophrenia should not marry at all (Magliano et al., 2004). Similarly, in another study, 100% of respondents agreed that they would not want their sister to marry someone with a mental disorder (Aydin et al., 2003). The majority of these respondents (76.2%, 32/42), also agreed that they would not rent their apartments to mentally ill people (Aydin et al., 2003).

Perceived dangerousness

Studies presented mixed attitudes and beliefs regarding the level of dangerousness, unpredictability, and emotional instability of mentally ill. Serafini et al., (2011) reported that 16 of 40 nurses (40%) considered patients with schizophrenia to be dangerous, while Munro and Baker (2007) reported that 85% of respondents did not. Kukulu and Ergun (2007) reported that over half of nurses (53%) agree they would be frightened if people with mental illness lived close by.

Severely mentally ill people were perceived as unpredictable (from 75% to 86% agreement). Questions concerning the lack of control over emotions showed mixed opinions. Hamdan-Mansour and Wardam, (2009) reported that 84.8% of the 92 nurses agreed with the statement that: “mentally ill have no control over their emotions”, while Foster et al., (2008) reported the opposite with almost 70% of nurses disagreeing with the following statement: “mentally ill patients have no control over the emotions”.

Schizophrenia and depression

Three studies compared specific attitudes toward schizophrenia and depression (Aydin et al., 2003; Hsiao et al., 2015; Nordt et al., 2006). Attitudes were generally more positive toward patients with depression. The comparisons included discrimination toward housing, use of services, work and proximity in social settings, such as their comfort level working with someone who has a mental illness. Aydin et al., (2003) reported that more nurses would be disturbed if they had to shop at a market run by a person with schizophrenia (33.3%) rather than the depression (11.1%). While 38.1% of nurses would be disturbed to work with a person with schizophrenia, only 5.9% would feel that way working with a person with depression. However, in some social situation, discrimination toward people with depression or schizophrenia were at the same level: 100% of respondents would not want their sisters to marry either one, 76% would not go to a hairdresser with either disorder and 76% would not rent a house to any of them. Hsiao et al., (2015) and Nordt et al., (2006) findings supported that nurses had more negative attitudes toward patients with schizophrenia rather than major depression.

Discussion

The studies included in this review examined nurse attitudes toward mental illness across 20 countries. Globally, nurses tend to have mixed attitudes toward different aspects of mental illness. Evidence about the difference in attitudes of psychiatric nurses and non-psychiatric nurses was contradictory. However, one study determined that the higher the education level of the nurse, the more likely the nurse would have a more positive attitude about mental illness. This suggests that education regarding mental illness could potentially alleviate negative attitudes associated with mental illness among nurses. Furthermore, the mixed attitudes found in this review may be partially explained by different cultural beliefs. Among the eight studies conducted in one or more European countries, both positive and negative nursing attitudes were reported, both within and across countries (Arvaniti et al., 2009; Chambers et al., 2010; Linden & Kavanagh, 2012; Magliano et al., 2004; Munro & Baker, 2007; Nordt et al., 2006; Scheerder et al., 2011; Serafini et al., 2011). In contrast, the majority of studies conducted in Middle Eastern or Asian countries, reported more negative than positive nursing attitudes, suggesting that culture may play an influential role in nursing perception of mental illness.

Another factor that might have contributed to the finding that nurses’ attitudes toward the mentally ill were quite mixed was the fact that various measurement tools were used. More than half of the studies (8/14) used different tools. Three tools alone were questionnaires adapted by researchers. This makes the comparisons of results across studies difficult.

Finally, the results of this study were surprising in that professional nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness were comparable to attitudes among the general public rather than reflective of professional expertise (Al-Krenawi, Graham, Dean, & Eltaiba, 2004; Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006; Ozmen et al., 2004; Schomerus et al., 2012; Tsang, Tam, Chan, & Cheung, 2003). One would anticipate that professional training would have an impact on attitudes toward these patients. The fact that nurses who worked on psychiatric units did not express more positive attitudes toward their patients as compared to nurses who worked in general medicine might be due to perception bias. These nurses often see patients readmitted for care with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations, which may influence their attitude toward mental illness capacity and prognosis. Linden and Kavanagh (2011) support this explanation, in that nurses from mental health community settings who worked with more stable patients endorsed more positive attitudes than those who worked on acute inpatient wards. If nurses have clear guidelines regarding how to approach patients with various mental illnesses, how to address their symptoms, and what therapeutic interventions are most effective, they may feel more empowered in their nursing roles, thus promoting a more positive outlook on mental illness. Further, management can be influential by providing explicit and overt support for culture change toward more supportive attitudes of patients diagnosed with mental illness.

Limitations

This review has some limitations. The English language limitation as well as the limited number of databases searched might have led to omission of relevant studies. Furthermore, we did not include the grey literature in this review.

Conclusions and Future Research

In summary, this review found that nursing attitudes toward people with mental illness varied, both within and across countries and mimicked attitudes similar to the general public. Since no studies were conducted in the U.S., there is a need to examine the attitudes of nurses toward those with mental illness and compare the U.S. to other countries. It is crucial to assess nurses’ attitudes toward mental illness and explore the factors associated with positive beliefs. A better understanding of mental illness and related nursing attitudes will help to inform delivery of care to those patients who suffer from mental illness.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

This review was funded by the Jonas Center For Nursing and Veteran Healthcare and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Comparative and Cost-Effectiveness Research Training for Nurse Scientists, T32 NR014205.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Facts and Statistics. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.adaa.org/about-adaa/press-room/facts-statistics.

- Adorno TW. The Authoritarian personality. 1. New York: Harper; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. 2. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Krenawi A, Graham JR, Dean YZ, Eltaiba N. Cross-national study of attitudes towards seeking professional help: Jordan, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Arabs in Israel. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2004;50(2):102–114. doi: 10.1177/0020764004040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: A review of population studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(3):163–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Social distance towards the mentally ill: results of representative surveys in the Federal Republic of Germany. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(1):131–141. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkar H. The social refusing of mental health patient. Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological. 1991;(4):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Arvaniti A, Samakouri M, Kalamara E, Bochtsou V, Bikos C, Livaditis M. Health service staff’s attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(8):658–665. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin N, Yigit A, Inandi T, Kirpinar I. Attitudes of hospital staff toward mentally ill patients in a teaching hospital, Turkey. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003;49(1):17–26. doi: 10.1177/0020764003049001544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA, Richards DA, Campbell M. Nursing attitudes towards acute mental health care: Development of a measurement tool. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49(5):522–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett MS, Chua WJ, Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MB, Casiano D, Thompson DON. Early withdrawal from mental health treatment: implications for psychotherapy practice. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill) 2008;45(2):247–267. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental Illness. Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers M, Guise V, Välimäki M, Botelho MA, Scott A, Staniuliené V, Zanotti R. Nurses’ attitudes to mental illness: A comparison of a sample of nurses from five European countries. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47(3):350–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu-Yueh H, Huei-Lan L, Yun-Fang T. Factors influencing mental health nurses’ attitudes towards people with mental illness. Internation Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2015;24(3):272–280. doi: 10.1111/inm.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, …Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How Stigma Interferes With Mental Health Care. American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Mittal D, Reaves CM, Haynes TF, Han X, Morris S, Sullivan G. Mental health stigma and primary health care decisions. Psychiatry Research. 2014;218(1):35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’osso B, Glick ID, Baldwin DS, Altamura AC. Can Long-Term Outcomes Be Improved by Shortening the Duration of Untreated Illness in Psychiatric Disorders? A Conceptual Framework. Psychopathology. 2012;46(1):14–21. doi: 10.1159/000338608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000338608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward K, Munro I. Nursing considerations for dual diagnosis in mental health. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2009;15(2):74–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eker D, Arkar H. Experienced Turkish Nurses’ Attitudes towards mental illness and the predictor variables of their attitudes. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1991;37(3):214–222. doi: 10.1177/002076409103700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S, Brohan E, Mojtabai R, Thornicroft G. Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(8):1741–1752. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I, Albarracin D, Hornik RC. Prediction and change of health behavior: applying the reasoned action approach. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foster K, Usher K, Baker JA, Gadai S, Ali S. Mental health workers’ attitudes toward mental illness in Fiji. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;25(3):72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighat R. The development of an instrument to measure stigmatization: Factor analysis and origin of stigmatization. The European Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;19(3) doi: 10.4321/S0213-61632005000300002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan-Mansour AM, Wardam LA. Attitudes of Jordanian mental health nurses toward mental illness and patients with mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30(11):705–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Stier A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annual Revue of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:367–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245. doi:0.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DL, Dukes EM, Wittchen HU. Human and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(1):72–90. doi: 10.1002/da.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Grossman SH, Auchterlonie JL, Riviere LA, Milliken CS, Wilk JE. PTSD treatment for soldiers after combat deployment: Low utilization of mental health care and reasons for dropout. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(8):997–1004. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, et al. Physician empathy: Definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EP, Corrigan PW, Williams P, Canar J. Changing attitudes about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25(3):447–456. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Smith &, Hood HV. Medical students’ attitudes toward AIDS and homosexual patients. Journal of medical education. 1987;62(7):549–556. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PY, Britt TW, Klocko RP, Riviere LA, Adler AB. Stigma, negative attitudes about treatment, and utilization of mental health care among soldiers. Military Psychology. 2011;23(1):65–81. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.534415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kukulu K, Ergun G. Stigmatization by nurses against schizophrenia in Turkey: A questionnaire survey. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2007;14(3):302–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01082.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. British medical journal (Clinical research ed) 2009 Jul 21;339(1):b2700–b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden M, Kavanagh R. Attitudes of qualified vs. student mental health nurses towards an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68(6):1359–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luty J, Fekadu D, Umoh O, Gallagher J. Validation of a short instrument to measure stigmatised attitudes towards mental illness. The Psychiatrist. 2006;30(7):257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Madianos MG, Madianou D, Vlachonikolis J, Stefanis CN. Attitudes towards mental illness in the Athens area: implications for community mental health intervention. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1987;75(2):158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magliano L, De Rosa C, Fiorillo A, Malangone C, Guarneri M, Marasco C … Working Group of the Italian National, S. Beliefs of psychiatric nurses about schizophrenia: a comparison with patients’ relatives and psychiatrists. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2004;50(4):319–330. doi: 10.1177/0020764004046073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DD, Frakes M, Apostolidis B, Armstrong B, Goldblatt S, Bernardo D. Effect of a psychiatric diagnosis on nursing care for nonpsychiatric problems. Research in Nursing & Health. 2003;26(3):225–232. doi: 10.1002/nur.10080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, … Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Baker JA. Surveying the attitudes of acute mental health nurses. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing. 2007;14(2):196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Mental Illness Facts and Numbers. Washington, DC: CDC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Newman D, O’Reilly P, Lee SH, Kennedy C. Mental health service users’ experiences of mental health care: an integrative literature review. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing. 2015;22(3):171–182. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIMH. Any Mental Illness Among Adults. Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nordt C, Rössler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(4):709–714. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Mojtabai R, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Druss B, Wang PS, … Kessler RC. Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):898–907. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen E, Ogel K, Aker T, Sagduyu A, Tamar D, Boratav C. Public attitudes to depression in urban Turkey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2004;39(12):1010–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0843-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reneses B, Munoz E, Lopez-Ibor JJ. Factors predicting drop-out in community mental health centres. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(3):173–177. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerder G, Van Audenhove C, Arensman E, Bernik B, Giupponi G, Horel AC, … Hegerl U. Community and health professionals’ attitude toward depression: A pilot study in nine EAAD countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2011;57(4):387–401. doi: 10.1177/0020764009359742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, Corrigan PW, Grabe HJ, Carta MG, Angermeyer MC. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;125(6):440–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G, Pompili M, Haghighat R, Pucci D, Pastina M, Lester D, … Girardi P. Stigmatization of schizophrenia as perceived by nurses, medical doctors, medical students and patients. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing. 2011;18(7):576–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01706.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevigny R, Yang W, Zhang P, Marleau JD, Yang Z, Su L, … Wang H. Attitudes toward the mentally ill in a sample of professionals working in a psychiatric hospital in Beijing (China) International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1999;45(1):41–55. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ, Court H, McLean G, Martin D, Langan Martin J, Guthrie B, … Mercer SW. Depression and multimorbidity: A cross-sectional study of 1,751,841 patients in primary care. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2014;75(11):1202–1208. doi: 10.4088/jcp.14m09147. quiz 1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Dear MJ, Hall GB. Attitudes toward the mentally ill and reactions to mental health facilities. Social Science & Medicine. Part D: Medical Geography. 1979;13(4):281–290. doi: 10.1016/0160-8002(79)90051-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0160-8002(79)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1981;7(2):225–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang HWH, Tam PKC, Chan F, Cheung WM. Stigmatizing attitudes towards individuals with mental illness in Hong Kong: Implications for their recovery. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(4):383–396. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, … Vos T. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]