Abstract

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that suggests that multiple social identities – e.g. race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation – intersect at the individual or micro level of experience and reflects larger social-structural inequities experienced on the macro level. This article uses an intersectionality framework to describe how multiple stigmatized social identities can create unique challenges for Young Black gay and bisexual men (YBGBM) as an example. YBGBM exist at the intersection of multiple stigmatized identities compared to their majority peers. There is limited health-focused research on the intersecting identities of YBGBM. Using the lens of intersectionality to understand challenges to health-related behaviors and threats to health and well-being for YBGBM may reveal key opportunities for prevention and intervention for YBGBM and other gay and bisexual men from other ethnic groups. In this article, we examine the key intersecting identities (race, sexual identity, socioeconomic status, and cultural expectations (such as gender norms/masculinity, religious morality), that exist in YBGBM and how those factors may predispose young men to adverse health outcomes and health inequality.

Background

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that suggests that multiple social identities – e.g. race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation – intersect at the individual or micro level of experience and reflects larger social-structural inequities experienced on the macro level [5, 6]. This article uses an intersectionality framework to describe how multiple stigmatized social identities can create unique challenges for Young Black gay and bisexual men (YBGBM) as an example.

Adolescence is an important time of physical, social, emotional and cognitive growth and development in the life course[1]. The majority of sexual and gender minority (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) youth of color emerge from this period as healthy adults, having successfully achieved these developmental tasks [1]. However, relative to their majority peers, these youth face greater, formidable risks to their health and development [2]. Young Black gay and bisexual men (YBGBM), and other young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM), in particular, carry one of the greatest public health burdens in the U.S., disproportionately accounting for over half (55%) of all new HIV infections in young men who have sex with men (YMSM)[4]. YBGBM experience multiple inequities compared to their majority peers by virtue of their membership in multiple oppressed and marginalized groups.

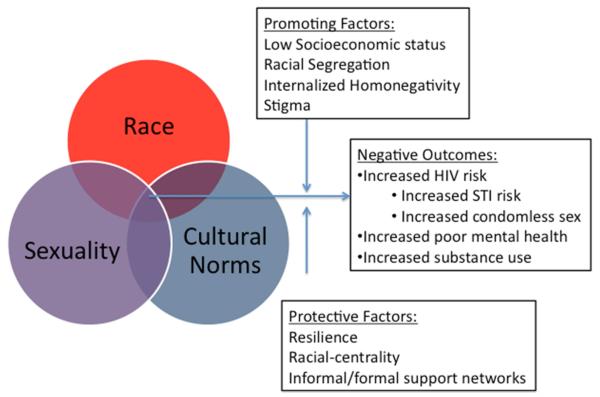

There is limited health-focused research on the intersecting identities of young Black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men [5, 7] but using the lens of intersectionality to understand the threats to health and well-being these young men face may provide key opportunities for prevention and intervention. In this article, we examine the key intersecting identities such as race, sexual identity, and cultural expectations (e.g. masculinity, and religious morality) (Figure 1), that exist in YBGBM and how such factors may predispose young men to adverse health outcomes and health inequality. We also describe socio-contextual promoting and protective factors that may further modify this relationship as well as clinical pearls that practitioners can use to help mitigate risk and negative outcomes in YBGBM. While this article predominantly focuses on HIV risk in YBGBM, many of the key concepts described in this article, such as intersectionality, can be applied to the lived experiences of all LGBT youth that occupy multiple identities.

Figure 1.

Key intersecting identities of Young Black gay and bisexual men

Racial and Sexual identities

One of the key tasks of adolescence is identity development, [8] a stage where adolescents and emerging adults come to understand the specific ways in which they fit into society. This task involves developing one’s self-concept which includes both personal identity or perception of self [8] and group identities – i.e. membership and identification with a group of people with shared characteristics salient to an individual’s self-concept [9]. Racial or ethnic identity, for example, is a group identity based on common heritage and a common sense of identity, affecting one’s internal self-concept and interactions with others [10]. Racial/ethnic identity is oftentimes more significant to the self-concept among ethnic minorities and racially oppressed groups [11]. Several theorists have argued that racial identity may be more salient for Blacks relative to Whites overall because of specific discrimination and racial prejudice Blacks have historically faced in the U.S. [12] and the shared struggle for equity and acceptance within the majority population [11, 12].

Sexual identity development in YBGBM, involves two related processes: identity formation – awareness, questioning and exploration of sexuality – and identity integration – incorporation of sexuality into one’s self-concept. Identity integration has been further conceptualized as involvement in lesbian-, gay-, or bisexual- (LGB) related social activities, resolving homo-negative attitudes, becoming comfortable with others knowing about a LGB sexual identity, and disclosing sexual identity to important others [13]. Identity formation and integration of developmental processes are often non-linear and variable across and within individuals. This variability is normal, but difficult or delayed identity integration has been associated with poor markers of psychosocial adjustment in youth including depression and anxiety, conduct problems, and poor self-esteem [13].

Disclosing sexual identity or “coming out” is not uniformly adaptive; rather the benefit of coming out depends on social context [14]. Norm compliance and collectivism rather than individualism and self-expression in racial/ethnic minority groups may be more important in the process of sexual identity development in sexual minorities of color than uniform disclosure seen in other groups [15]. For example, Legate et al (2011) found coming out was associated with higher self-esteem and less depression and anger in autonomy-supportive contexts (i.e. interpersonal support for authentic self-expression) but not in controlling social contexts (i.e. interpersonal pressure to conform to socio-behavioral norms) [14]. As such, affiliation with sexual minority communities and LGB-related social events has been described as less relevant for YBGBM [16].

Additionally, YBGBM may experience a conflict between same-sex sexuality and homo-negative (i.e., heterosexist, antigay) cultural expectations of masculinity and religious morality [17, 18]. Because of this conflict, some YBGBM may experience or fear that they will experience rejection, ridicule, and isolation from family, peers and community during key moments in adolescent development. For a group that often identifies first with their racial identity [19, 20], and draws strength and support from that community [21], preserving that connection may be paramount to “coming out” or otherwise embracing or assuming a gay/bisexual identity [22, 23]. Rather than risking that connection, an individual, whose dominant identity is his racial identity, may compartmentalize his sexual identity [23]. In this context, nondisclosure of sexuality may be protective and adaptive by allowing the individual to preserve important social supports [24]. However, as sexual and racial minority youth, the internal conflict some young men wage between cultural expectations and their sexuality may further isolate them at a time when interpersonal attachments are important [25], particularly if this conflict precludes them from accessing other, appropriate sources of social support related to their sexuality [26].

Cultural Norms/Expectations

Masculinity

Normative and dominant masculinity in American culture has been described as anti-feminine, homophobic, heterosexist, and misogynistic. [27] Some have suggested that stereotypical male gender roles of hyper-masculinity (i.e., exaggeration of traditional masculine roles through behaviors such as sexual prowess, physical dominance, aggression, competition, and anti-femininity) seen in some Black men may be a way for Black men disempowered by a social context of limited access to socioeconomic power, racism, and discrimination by a predominantly White male society to demonstrate power and authority [22, 28] and to approximate the American masculine ideal.

This compensatory expression of hyper-masculinity has been suggested as an important coping strategy for racism, oppression and marginalization particularly in young Black men. Majors’ and Billson’s [28] conceptual framework “Cool Pose,” describes a hyper-masculine strategy embraced by Black males to cope with and survive in the face of social oppression and racism. Lacking the resources to obtain the traditional American societal prescription for masculinity, “Cool Pose” fosters the development of compulsive masculinity as an alternative to traditional definitions of manhood that “compensates for feelings of shame, powerlessness and frustration” by typifying toughness, sexual promiscuity, and violence to resolve personal conflicts [28].

The expression of hyper-masculinity among Black men has also been associated with community and peer acceptance as well as fortification of self-image and self-esteem [29]. In contrast to the expression of hyper-masculinity, disclosure of homosexuality has been associated with depressive distress, alienation and social isolation within Black communities [30]. These social sanctions are due, in part, to perceived direct contradictions between “hyper-masculine” gender role expectations for Black men and association of homosexuality with exaggerated stereotypes of being weak and effeminate [31, 32]. YBGBM may alter their presentation or expression of masculinity as a strategy to either avoid ridicule or to fit in and maintain social ties with important others [33, 34].

While maximizing social reward and avoiding social sanctions are strong motivators, achieving or striving for these homo-negative masculine expectations carries significant risk for young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM). Fields, et al (2015) applied Gender Role Strain theory to a sample of YBMSM who felt pressured to conform to homo-negative expectations of masculinity from important others – e.g. family, peers and community. In this analysis they found examples of psychosocial distress, efforts to camouflage or hide same-sex behavior and identity, strategies to prove one’s masculinity and the potential for increased HIV risk through social isolation, poor self-esteem, reduced access to HIV prevention messages, and limited parental involvement in sexuality development and exploration [33]. Moreover, the norm of nondisclosure of same-sex behavior in Black communities where homosexuality is viewed as incompatible with masculine expectations [18, 27, 33] can create opportunities for HIV risk for YBGBM, including exploration of sexuality in hidden, high risk, often age-discordant settings such as the internet and telephone-based venues.

Religion

Religiosity and religious affiliation has generally been associated with positive mental and physical health outcomes in both cross sectional and prospective studies [35, 36]. However among sexual minorities, the beneficial impact of religion is less clear. Religious affiliation, while protective in some ways, has also been associated with mental health pathology in YBGBM including psychological distress, depression, poor self-esteem, and internalized homophobia [37]. This relationship between religious affiliation and internalized homophobia has been described by minority stress theory which posits that health disparities affecting sexual minorities are the result of differential exposure to stigma, homophobia, and rejection [38] (see Ch. 5). As a result of this process, some LGB youth may disassociate more from institutional religion as a coping strategy to avoid the stressors associated with homo-negative and potentially stigmatizing social environments [39].

The salience of religiosity in Black communities may limit the value and relevance of disassociation as a coping strategy for YBGBM. The Black Church, a term that refers to the seven historically Black protestant denominations founded after the Free African Society of 1787 and representing over 80% of Black Christians in the U.S. [40], is a central religious, social and cultural institution in Black American society. It is uniformly recognized as the most influential institution in Black American society [40] and has been at the center of social and political activity throughout history, leading the Civil Rights movement, and other social justice issues related to racial oppression and discrimination [41]. The Black Church has also been a refuge from discrimination and marginalization for Black communities [41]. Upwards of 80% report religion as an important part of their lives, [42] and for many of these individuals religion and affiliation with the Black Church as a religious and socio-cultural institution are salient to both their self-concept and their Black identity [43], [44].

While Black churches are not a monolithic entity and do not uniformly object to homosexuality, many, like other religious institutions, do espouse proscriptive messages against same-sex behavior and identities [41]. The Black Church as an institution has generally been described as homophobic and intolerant of same-sex sexuality [41] and is one of the principal sources of homo-negative messages in Black communities, [32, 34, 41] influencing church goers and non-churchgoers alike. In some churches, this message is manifested as silence during the AIDS crisis [41] and in others, the message manifests as explicit and consistent condemnation of homosexuality and homosexual persons [31, 34]. This is sometimes replicated in families, among peers, and in the larger community. In addition to the morality of homosexuality, the conflation of gender and sexuality in masculine socialization described above is also entwined in the homo-negative messages, [32] which further emasculates such men by making them incapable of meeting expectations for men in the church or in the larger community [32, 45].

YBGBM are challenged with significant conflict at the intersection of their same-sex behavior and sexual identity, racial identity, and religiosity. For many the church environment is highly salient to other aspects of their multiple and intersecting identities and central to Black American life and Black racial identity [44]. In studies of YBGBM experiences with religiosity, many describe managing this conflict by compartmentalizing their sexual identity within religious contexts. Balaji et al (2012) in a qualitative study of 16 young (19-24) YBMSM, described study participants engaging in ‘role-flexing,’ a strategy for maintaining masculine expectations and camouflaging/concealing sexual orientation to avoid exposure to direct homo-negative prejudice in religious settings [34]. This strategy may place youth, particularly those who have not integrated their sexual identity into their sense of self (i.e. identity integration), at risk for internalizing many of the homo-negative messages they seek to avoid [31, 34]. Others, often older adults, described managing this conflict by integrating their religiosity and sexuality through attending religious (often non-Black or non-Christian) institutions that affirmed same-sex sexuality, creating new religious communities outside of traditional church environments, abandoning institutional religion in favor of a more personal, individual relationship with a higher power, or remaining in traditional Black religious institutions and rejecting homo-negative or non-affirming messages [48, 49].

Promoting Factors

In the preceding sections we provided a conceptual approach to understanding how intersecting identities like race, gender, and culture impact one’s risk for adverse health outcomes. Marginalization for YBGBM can be further promoted by factors like poverty and low socioeconomic status, racial segregation, homo-negativity, stigma and limited social connectedness. YBGBM, for example, are often disproportionately burdened by the socioeconomic inequity and poor social and built environment that increases risk for HIV and other poor outcomes relative to their White sexual minority peers [58]. Table 1 reviews these promoting factors further and summarizes how these factors increase risk for HIV and other health and social disparities for YBGBM. Factors such as poverty, social environment (including racial segregation), homonegativity, stigma, and limited social connectedness can further isolate YBGBM predisposing them for risk. Such factors further perpetuate macro-level factors that impact on the individual level.

Table 1.

Promoting factors affecting adverse health outcomes among YBGBM

| Domain | Key Points |

|---|---|

|

Socioeconomic

Status and the Structural, Social and Built Environment |

|

|

Racial

Segregation of Sexual Networks and HIV Risk |

|

|

Internalized

Homo-Negativity (IH) |

|

| Stigma |

|

|

Limited Social

Connections |

|

Protective Factors

Despite the prevalence of stigma, discrimination, and marginalization, most YBGBM are remarkably resilient, develop coping strategies, build social support networks, and have good mental health [87]. YBGBM often have access to several protective factors despite the challenges they face as sexual and racial/ethnic minorities. Aspects of their dual, intersecting identities that may create adversity (strong ties to racial/ethnic communities, religious or spiritual faith) also tend to be sources of strength. Table 2 reviews racial centrality, resilience, religiosity and spirituality, and social support and how these factors can be protective in the lives of YBGBM. These factors can sometimes buffer the negative effect of existing within multiple marginalized identities. For example, prior work suggests that for some YBGBM a positive societal view of Black men was associated with decreased sexual risk behavior [89].

Table 2.

Protective factors affecting the health of YBGBM

| Domain | Key Points for Primary Care Providers |

|---|---|

| Race Centrality |

|

| Resilience |

|

|

Religiosity and

Spirituality |

|

| Social Support |

|

Clinical Considerations

YBGBM are a unique population existing at the intersection of four often medically underserved groups – male, young, Black, and sexual minority. Additionally, many often are from economically depressed settings. Each of these groups has historically had poor relationships with health care settings. Males are less likely to access primary care, health promotion or preventive services compared to female patients [94]. Youth have similar barriers; a normal component of adolescent development is the illusion of invulnerability and invincibility; however this illusion has been correlated with risk behaviors and poor engagement in health care and health promotion [95]. Black individuals have characteristically had low levels of health care utilization as a result of historical and contemporary barriers to care including financial and structural access barriers, medical mistrust, and history of unequal and maltreatment [96]. Sexual minorities have similarly had barriers to care resulting from poor cultural competency and low provider knowledge of the health care needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals [97]. While disparities in HIV may have increased access to HIV testing and other preventive health services in underserved areas, those in economically depressed areas have significant barriers to care including cost and insurance [98], transportation [99], and competing socioeconomic needs (e.g. employment, food, housing).

YBGBM at the intersection of all of these social categories face all of these challenges. Moreover, these challenges are not simply additive, rather, they are interdependent and mutually reinforcing [5, 6]. Very few studies have explored the health care experiences of YBGBM. While some have focused on primary care or preventive health services the majority focus on engagement and retention of HIV-infected youth. Reflecting the multiple challenges above, these studies have found the following factors were positively associated with treatment engagement, retention and health care utilization: feeling respected in clinical settings, receipt of social services ethnic identity affirmation, and employment [79], while negative self-image, medical mistrust, racial and sexual orientation stigma from providers, and stigma disclosing same-sex behavior were negatively associated [79]. In a qualitative study, adult Black MSM described experiences of racial and sexual discrimination in medical settings that compounded similar experiences in other aspects of their lives and negatively impacted their medical utilization, HIV testing, communication with providers and medication/treatment adherence [100].

Summary and Recommendations

We have used an intersectionality framework to describe how occupying multiple stigmatized social identities can create unique challenges for YBGBM as an example. Such intersection can predispose YBGBM to risk and poor health outcomes. Young Black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men must achieve the tasks of adolescence at the intersection of multiple social categories such as race, socioeconomic status, gender (and gender expression), religion and sexuality. This experience is compounded by multiple threats to their health and well-being from their social environment at the interpersonal, intermediate structural, and macro-structural levels. These threats reflect the social inequities this group is disproportionately burdened with as members of multiple oppressed and marginalized groups.

When caring for YBGBM, it is important bear in mind the importance of culture, family and religion in identity development and to assess the following: 1) the social context in which the adolescent lives in (in order to assess contextual factors that may predispose some YBGBM to risk); 2) a youth’s identities, including racial, sexual and cultural group identity; 3) to whom youth have disclosed their sexual orientation; and 4) whether they must exist in certain environments (hypermasculine, religious, etc) that prohibit them from disclosing their sexual orientation to others.

Clinicians should also keep in mind that promoting factors (e.g., racial segregation, homonegativity and stigma) could modify exposure to risk to increase poor outcomes, while protective factors (e.g., resilience, race-centrality and social support) may help to protect YBGBM from risk. While this article focused primarily on YBGBM, the intersectionality framework discussed here is also an important lens for other LGBT youth of color and other racial/ethnic groups who may have to cope with specific sociocultural factors related to sexual orientation, gender expression or gender identity that influence health outcomes. Clinicians should be aware of the unique challenges that impact sexual and gender minority groups that occupy multiple marginalized circles in order to adequately assess, develop programs and cultivate skills in YBGBM that promote protective factors and block the impact of negative promoting factors.

Key Points.

Young Black Gay and Bisexual Men (YBGBM) in particular experience multiple inequities compared to their majority peers by virtue of their membership in multiple oppressed and marginalized groups.

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework that suggests that multiple social identities – e.g. race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation – intersect at the individual or micro level of experience and reflects larger social-structural inequities experienced on the macro level.

Intersecting identities predispose YBGBM to adverse health outcomes and health inequality, which are further modified by promoting and protective factors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Errol Fields, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 200 N. Wolfe Street, #2027, Baltimore, MD 21287, errol.fields@jhmi.edu.

Anthony Morgan, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 200 N. Wolfe Street - Room 2069, Baltimore, MD 21287, Amorga28@jhu.edu.

Renata Arrington Sanders, Division of General Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 200 North Wolfe Street, Room 2063, Baltimore, Maryland 21287.

References

- 1.Levine DA, et al. Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e297–e313. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruce D, Harper GW. Operating without a safety net: gay male adolescents and emerging adults' experiences of marginalization and migration, and implications for theory of syndemic production of health disparities. Health Education & Behavior. 2011:1090198110375911. doi: 10.1177/1090198110375911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collier KL, et al. Sexual orientation and gender identity/expression related peer victimization in adolescence: A systematic review of associated psychosocial and health outcomes. Journal of sex research. 2013;50(3-4):299–317. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.750639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control Prevention Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007-2010. HIV surveillance supplemental report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowleg L. “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11-12):754–767. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamil OB, Harper GW, Fernandez MI. Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay–bisexual–questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(3):203. doi: 10.1037/a0014795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erikson EH. Growth and crises of the" healthy personality.". 1950.

- 9.Tajfel H. European studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, New York, Paris: 1982. Social identity and intergroup relations; p. xv.p. 528. Editions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helms JE. Introduction: Review of racial identity terminology. In: Helms JE, editor. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. Wesport, CT; Praeger: 1990. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phinney JS. Ethnic identity exploration in emerging adulthood. In: Browning DL, Browning DL, editors. Adolescent identities: A collection of readings. The Analytic Press/Taylor & Francis Group; New York, NY, US: 2008. pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phinney JS. When We Talk About American Ethnic Groups, What Do We Mean? American Psychologist. 1996;51:918–927. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Different patterns of sexual identity development over time: implications for the psychological adjustment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. J Sex Res. 2011;48(1):3–15. doi: 10.1080/00224490903331067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Legate N, Ryan RM, Weinstein N. Is coming out always a “good thing”? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;3(2):145–152. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Constantine MG, et al. Independent and Interdependent Self-Construals, Individualism, Collectivism, and Harmony Control in African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2003;29(1):87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moradi B, et al. LGB of color and White individuals’ perceptions of heterosexist stigma, internalized homophobia, and outness: Comparisons of levels and links. The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38(3):397–424. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields EL, et al. HIV risk and perceptions of masculinity among young black men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(3):296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malebranche DJ, et al. Masculine socialization and sexual risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Men and Masculinities. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cross WE, Parham TA, Helms JE. In: The stages of Black identity development: Nigrescence models, in Black psychology. Jones R, editor. Cobb & Henry Publishers; Berkeley, CA: 1991. pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cross WE. In: The psychology of nigrescence: Revising the Cross model, in Handbook of multicultural counseling. Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, editors. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez DG, Sullivan SC. African American Gay Men and Lesbians: Examining the Complexity of Gay Identity Development. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 1998;1(2/3):243–264. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehead TL, Peterson JL, Kaljee L. The" hustle": socioeconomic deprivation, urban drug trafficking, and low-income, African-American male gender identity. Pediatrics. 1994;93(6):1050–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malebranche DJ, et al. Masculine Socialization and Sexual Risk Behaviors among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Exploration. Men and Masculinities. 2007:1097184X07309504v1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frable DE, Platt L, Hoey S. Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: feeling better around similar others. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(4):909–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nesmith AA, Burton DL, Cosgrove TJ. Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Youth and Young Adults: Social Support in Their Own Words. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37:95–108. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman L, et al. Resilience in Community: A Social Ecological Development Model for Young Adult Sexual Minority Women. American journal of community psychology. 2015;55(0):179–190. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9702-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connell RW. Masculinities. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majors RG, Billson JM. Cool pose: the dilemmas of black manhood in America. DC Heath and Co; Lexington, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter AG, Davis JE. Hidden Voices of Black Men: The Meaning, Structure, and Complexity of Manhood. Journal of Black Studies. 1994;25(1):20–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Homophobia, self-esteem, and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10(3):278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J. Homonegativity, Religiosity, and the Intersecting Identities of Young Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward EG. Homophobia, hypermasculinity and the US black church. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(5):493–504. doi: 10.1080/13691050500151248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fields EL, et al. “I Always Felt I Had to Prove My Manhood”: Homosexuality, Masculinity, Gender Role Strain, and HIV Risk Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(1):122–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balaji AB, et al. Role Flexing: How Community, Religion, and Family Shape the Experiences of Young Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2012;26(12):730–737. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hackney CH, Sanders GS. Religiosity and Mental Health: A Meta–Analysis of Recent Studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58(1):36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnes DM, Meyer IH. Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(4):505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of health and social behavior. 1995:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herek GM, et al. Demographic, Psychological, and Social Characteristics of Self-Identified Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults in a US Probability Sample. Sex Res Social Policy. 2010;7(3):176–200. doi: 10.1007/s13178-010-0017-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The black church in the African American experience. Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE. Stigma as an Obstacle to AIDS Action: The Case of the African American Community. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42(7):1117–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahgal N, Smith G. A religious portrait of African Americans. The Pew forum on religion and public life. 2009.

- 43.Taylor RJ, et al. Black and White Differences in Religious Participation: A Multisample Comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35(4):403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilcox C, Gomez L. Religion, Group Identification, and Politics among American Blacks. Sociology of Religion. 1990;51(3):271–285. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffin H. Their own received them not: African American lesbians and gays in black churches. Theology and sexuality. 2000;6(12):88–100. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams GR, Marshall SK. A developmental social psychology of identity: understanding the person-in-context. Journal of Adolescence. 1996;19(5):429–442. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pitt RN. “Still Looking for My Jonathan”: Gay Black Men's Management of Religious and Sexual Identity Conflicts. Journal of Homosexuality. 2009;57(1):39–53. doi: 10.1080/00918360903285566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winder TA. “Shouting it Out”: Religion and the Development of Black Gay Identities. Qualitative Sociology. 2015:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koblin BA, et al. Correlates of HIV acquisition in a cohort of Black men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV prevention trials network (HPTN) 061. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e70413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lillie-Blanton M, Laveist T. Race/ethnicity, the social environment, and health. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43(1):83–91. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steptoe A, Feldman PJ. Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23(3):177–185. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2303_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Auerbach JD, Parkhurst JO, Cáceres CF. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: conceptual and methodological considerations. Global Public Health. 2011;6(sup3):S293–S309. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Browning CR, et al. Neighborhood Structural Inequality, Collective Efficacy, and Sexual Risk Behavior among Urban Youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49(3):269–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raymond HF, et al. The role of individual and neighborhood factors: HIV acquisition risk among high-risk populations in San Francisco. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(2):346–356. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jennings JM, et al. Sex Partner Meeting Places Over Time Among Newly HIV-Diagnosed Men Who Have Sex With Men in Baltimore, Maryland. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(10):549–53. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mustanski B, et al. The Role of Geographic and Network Factors in Racial Disparities in HIV Among Young Men Who have Sex with Men: An Egocentric Network Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(6):1037–1047. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0955-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huebner DM, et al. Social oppression, psychological vulnerability, and unprotected intercourse among young Black men who have sex with men. Health Psychology. 2014;33(12):1568. doi: 10.1037/hea0000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eaton LA, et al. Minimal Awareness and Stalled Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among at Risk, HIV-Negative, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2015;29(8):423–429. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Millett GA, et al. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. American journal of public health. 2006;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Millett GA, et al. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–2091. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oster AM, et al. Understanding disparities in HIV infection between black and white MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2011;25(8):1103–1112. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471efa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sullivan PS, et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.006. (0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amirkhanian Y. Social Networks, Sexual Networks and HIV Risk in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2014;11(1):81–92. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0194-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fields E, Fullilove R, Fullilove M. HIV sexual risk taking behavior among young Black MSM: Contextual factors. American Public Health Association Annual Meeting.2001. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jerome RC, Halkitis PN. Stigmatization, Stress, and the Search for Belonging in Black Men Who Have Sex With Men Who Use Methamphetamine. Journal of Black Psychology. 2009;35(3):343–365. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kraft JM, et al. Finding the "community" in community-level HIV/AIDS interventions: formative research with young African American men who have sex with men. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(4):430–41. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial Mixing and HIV Risk Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(4):630–637. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arrington-Sanders R, et al. 13. Intersecting Identities in Black Gay and Bisexual Young Men: A Potential Framework for HIV Risk. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56(2):S7–S8. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(8):1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berg RC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Ross MW. Internalized Homonegativity: A Systematic Mapping Review of Empirical Research. Journal of homosexuality. 2015 doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788. (just-accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shoptaw S, et al. Homonegativity, substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV status in poor and ethnic men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(1):77–92. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilson PA, et al. Contributions of Qualitative Research in Informing HIV/AIDS Interventions Targeting Black MSM in the United States. The Journal of Sex Research. 2015:1–13. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1016139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crawford I, et al. The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. The Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(3):179–189. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kennamer JD, et al. Differences in disclosure of sexuality among African American and White gay/bisexual men: Implications for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(6):519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):32. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bennett GG, et al. Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(2):238–240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hussen SA, et al. Psychosocial Influences on Engagement in Care Among HIV-Positive Young Black Gay/Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2015;29(2):77–85. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Arnold EA, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. ‘Triply cursed’: racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young Black gay men. Culture, health & sexuality. 2014;16(6):710–722. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin. 2003;129(5):674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haile R, et al. An Empirical Test of Racial/Ethnic Differences in Perceived Racism and Affiliation with the Gay Community: Implications for HIV Risk. Journal of Social Issues. 2014;70(2):342–359. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arrington-Sanders R, et al. The role of sexually explicit material in the sexual development of same-sex-attracted Black adolescent males. Archives of sexual behavior. 2015;44(3):597–608. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0416-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fields EL, et al. 232. The Role of Virtual Venues Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men (YBMSM): Exploration of Patterns of Use From 2001-2011. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;2(56):S118–S119. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cohen S. Social Relationships and Health. American Psychologist. 2004;59(8):676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ayala G, et al. Modeling the Impact of Social Discrimination and Financial Hardship on the Sexual Risk of HIV Among Latino and Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(S2):S242–S249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herek GM, Garnets LD. Sexual Orientation and Mental Health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3(1):353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dupree D, Spencer TR, Spencer MB. Youth Resilience and Culture. Springer; 2015. Stigma, Stereotypes and Resilience Identities: The Relationship Between Identity Processes and Resilience Processes Among Black American Adolescents; pp. 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walker JNJ, Longmire-Avital B, Golub S. Racial and Sexual Identities as Potential Buffers to Risky Sexual Behavior for Black Gay and Bisexual Emerging Adult Men. 2014 doi: 10.1037/hea0000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garofalo R, et al. Impact of Religiosity on the Sexual Risk Behaviors of Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. The Journal of Sex Research. 2015;52(5):590–598. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.910290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Detrie PM, Lease SH. The relation of social support, connectedness, and collective self-esteem to the psychological well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 2007;53(4):173–199. doi: 10.1080/00918360802103449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Frost DM, Meyer IH. Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(1):36–49. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.565427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arnold EA, Bailey MM. Constructing home and family: How the ballroom community supports African American GLBTQ youth in the face of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2009;21(2-3):171–188. doi: 10.1080/10538720902772006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wickman ME, Anderson NLR, Smith Greenberg C. The Adolescent Perception of Invincibility and Its Influence on Teen Acceptance of Health Promotion Strategies. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2008;23(6):460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Medicine I.o. In: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (full printed version) Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. p. 782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Medicine I.o. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. p. 368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weissman JS, et al. Delayed Access to Health Care: Risk Factors, Reasons, and Consequences. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1991;114(4):325–331. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-4-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Malmgren JA, Martin ML, Nicola RM. Health care access of poverty-level older adults in subsidized public housing. Public Health Reports. 1996;111(3):260–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Malebranche DJ, et al. Race and sexual identity: perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96(1):97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]