Abstract

Plant microRNAs (miRNAs) show a high degree of sequence complementarity to, and are believed to guide the cleavage of, their target messenger RNAs. Here, I show that miRNA172, which can base-pair with the messenger RNA of a floral homeotic gene, APETALA2, regulates APETALA2 expression primarily through translational inhibition. Elevated miRNA172 accumulation results in floral organ identity defects similar to those in loss-of-function apetala2 mutants. Elevated levels of mutant APETALA2 RNA with disrupted miRNA172 base pairing, but not wild-type APETALA2 RNA, result in elevated levels of APETALA2 protein and severe floral patterning defects. Therefore, miRNA172 likely acts in cell-fate specification as a translational repressor of APETALA2 in Arabidopsis flower development.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), ~22-nucleotide non-coding RNAs that regulate protein-coding RNAs, are processed from longer hairpin transcripts by the enzyme Dicer [reviewed in (1, 2)]. In Arabidopsis, the accumulation of miRNAs requires a Dicer homolog, DCL1, and a novel protein, HEN1 [reviewed in (3)]. The two founding members of Caenorhabditis elegans miRNAs, lin-4 and let-7, inhibit the translation of their target mRNAs through imperfect base-pairing interactions with their targets (4, 5). Arabidopsis miRNAs show a higher degree of sequence complementarity to their potential targets, and, like short interfering RNAs, several plant miRNAs direct the cleavage of their target RNAs (6–9). Here, I report the role of an Arabidopsis miRNA, miRNA172, in the control of floral organ identity and floral stem cell proliferation as a potential translational repressor of a floral homeotic gene.

Four organ types are specified in the floral meristem by the combinatorial actions of three classes of transcription factors, the floral A, B, and C genes [reviewed in (10)]. APETALA2 (AP2, a class A gene) and AGAMOUS (AG, a class C gene) specify the identities of the perianth and reproductive organs, respectively, and act antagonistically to restrict each other’s activities to their proper domains of action within the floral meristem. We have identified HEN1 as a gene required for class C activity in the flower, because recessive hen1 mutations result in reproductive-to-perianth organ transformation in the hua1-1 hua2-1 background, which is partially compromised in class C activity (11, 12). The requirement of HEN1 for the accumulation of miRNAs (13) suggests that the absence of a miRNA(s) is responsible for the floral homeotic transformation in hua1-1 hua2-1 hen1 flowers.

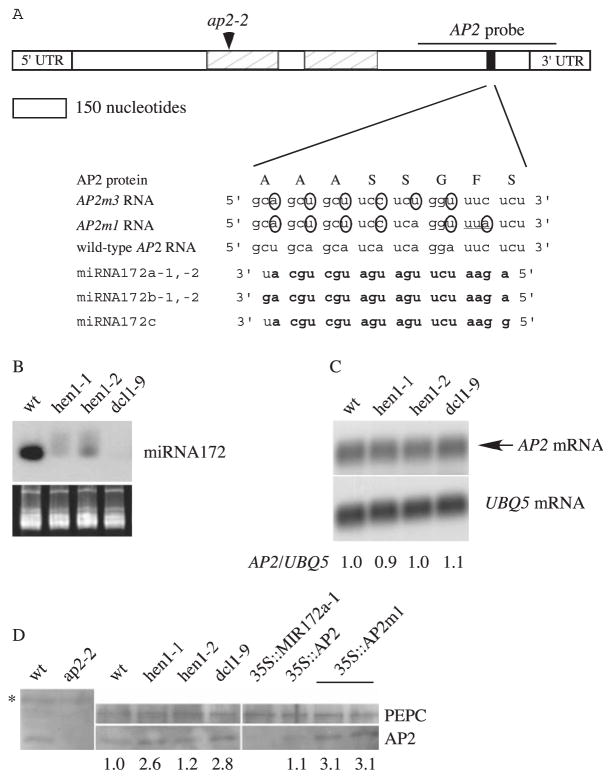

MiRNA172, a miRNA highly complementary to a region in the mRNAs of AP2 (14) (Fig. 1A), At2g28550, At5g60120, and At5g67180, which encode proteins with AP2 domains, is a candidate miRNA in flower development. The putative miRNA172 binding sites are located within the coding regions of the genes but are outside of the conserved AP2 domains. To test whether AP2 is regulated by miRNA172, I first studied AP2 expression in genotypes in which miRNA172 accumulates to low levels, such as hen1 and dcl1 mutants (Fig. 1B). AP2 RNA abundance in these genotypes was similar to that in wild type (Fig. 1C) (9). AP2 protein amounts in hen1 and dcl1 inflorescences, however, were about 2 to 3 times that in wild type (Fig. 1D), suggesting that AP2 is regulated at the translational or posttranslational levels by a miRNA(s) absent in hen1 and dcl1 plants. Elevated AP2 accumulation is likely the cause of the homeotic transformation in hua1-1 hua2-1 hen1-1 flowers, because a severe loss-of-function ap2 allele, ap2-2 (15), rescues the hua1-1 hua2-1 hen1-1 floral homeotic phenotypes (12).

Fig. 1.

Sequence complementarity between AP2 RNA and miRNA172 and AP2 RNA and protein accumulation in various genotypes. (A) A diagram of the AP2 mRNA showing the AP2 domains (hatched rectangles) and the miRNA172 binding site (black rectangle). The mutant nucleotides in AP2m1 and AP2m3 are circled. Although AP2m1 causes a Phe-to-Leu amino acid substitution (underlined codon), AP2m3 does not change the amino acid sequence. Nucleotides in miRNA172 that can base-pair with AP2 RNA (with G:U pairing allowed) are in bold. The ap2-2 allele is a splice acceptor site mutation that would generate a stop codon at the indicated position (arrowhead). 3′UTR, 3′ untranslated region; 5′UTR, 5′ untranslated region. (B) Accumulation of miRNA172 in inflorescences. The stained gel below indicates the amount of RNA in each lane. wt, wild type. (C) AP2 RNA abundance in inflorescences. The numbers indicate the relative abundance of AP2 RNA in various genotypes. (D) AP2 protein abundance in inflorescences. Although the AP2 antisera reacted with a number of proteins (one indicated by the asterisk), the identity of the AP2 signal was revealed by its absence in the ap2-2 mutant. The numbers indicate the abundance of AP2, as calculated by using phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) as the loading control.

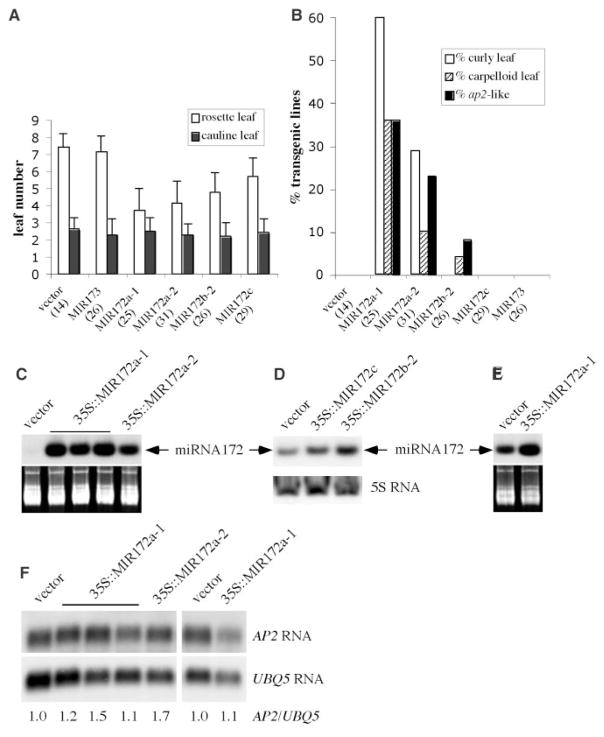

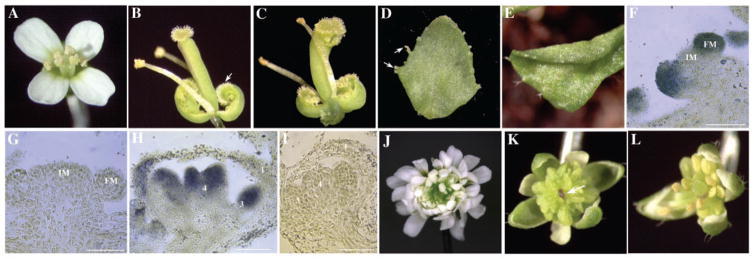

To determine whether AP2 is regulated by miRNA172, I tested the effect of elevated miRNA172 level on AP2 expression in planta. Five genes in the Arabidopsis genome (table S1) can give rise to three miRNA172 species with one nucleotide difference. All three miRNA172 species can base-pair with AP2 RNA with no or one mismatch (Fig. 1A). Each of four MIR172 genes, MIR172a-1, a-2, b-2, and c (13), was fused to two copies of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S enhancer, which drives high-level and near ubiquitous expression, and was introduced into wild-type plants. Most T1 transgenic lines containing each MIR172 gene but not MIR173 (an unrelated miRNA gene) or the vector alone displayed accelerated floral transition (Fig. 2A). In addition, plants harboring 35S::MIR172a-1, a-2, or b-2, but not 35S::MIR172c, the vector DNA, or 35S::MIR173, showed floral homeotic phenotypes similar to those of ap2 loss-of-function mutants, such as ap2-2 or ap2-9 (15) (Figs. 2B and 3, B and C). Similar phenotypes were also observed in an activation-tagging line that over-expressed miRNA172a-2 (16). Some cauline leaves of 35S::MIR172a-1, 35S::MIR172a-2, and 35S::MIR172b-2 lines had stigmatic tissues (Fig. 3D), suggesting elevated AG expression. Indeed, AG RNA accumulation was elevated in the cauline leaves of 35S::MIR172a-1 plants relative to control transgenic plants (fig. S1). Some 35S::MIR172a-1 and a-2 plants also had rosette leaves that curled upward (Fig. 3E), a phenotype found in plants expressing AG in leaves (17, 18). Because severe loss-of-function ap2 mutants do not have curly leaves or carpelloid leaves, the leaf phenotypes of 35S::MIR172 lines indicate that miRNA172 regulates, in addition to AP2, other genes that repress AG in leaves.

Fig. 2.

Analyses of 35S::MIR172 transgenic lines. (A) Leaf numbers of T1 transgenic lines. (B) Percentage of T1 transgenic lines with phenotypes that resemble plants with ectopic AG expression, such as curly leaves, carpelloid leaves, and ap2-like flowers. The total number of independent lines analyzed in (A) and (B) is in parentheses. The miRNA172 abundance in (C) 20-day seedlings of T2 lines, (D) 30-day T1 lines, and (E) inflorescences of T2 lines. The stained gels in (C) and (E) and the 5S rRNA hybridization in (D) indicate the amount of total RNA used. (F) AP2 RNA accumulation in 20-day seedlings (the five lanes on the left) and in inflorescences (the two lanes on the right) of T2 lines.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypes of 35S::MIR172, 35S::AP2, and 35S::AP2m1 lines and in situ localization of miRNA172. (A) A wild-type flower. (B) An ap2-9 flower with first-whorl organs transformed into carpels (arrow). (C) A 35S::MIR172a-1 flower that closely resembles ap2 flowers. A cauline leaf with stigmatic tissues (D, arrows) and a curly rosette leaf (E) from 35S::MIR172a-1 plants. In situ hybridization using an anti-sense [(F) and (H)] or sense [(G) and (I)] miRNA172 probe on longitudinal sections of inflorescence meristems (IM) with two young floral meristems (FM) [(F) and (G)] and stage 7 flowers [(H) and (I)]. Hybridization signals are represented by the blue color. Size bar, 50 μm. The numbers in (H) and (I) represent the positions of the organs, with 1 being the outermost whorl. (J) A 35S::AP2m1 flower with numerous petals and loss of floral determinacy. (K) A 35S::AP2m1 flower with many staminoid organs and an enlarged floral meristem (arrow). (L) A 35S::AP2 flower with more stamens than the wild type.

RNA filter hybridization showed that these transgenic lines had higher levels of miRNA172 (Fig. 2, C to E). Because the abundance of miRNA172 in wild-type plants is low in young seedlings and high in inflorescences (13), the increase in miRNA172 abundance in 35S::MIR172 lines was more evident in young seedlings than in inflorescences (Fig. 2, C and E). Despite the presence of ap2-like phenotypes in these lines, AP2 RNA accumulation was similar to that in control transgenic plants (Fig. 2F). AP2 protein, although readily detectable in wild type, was undetectable in 35S::MIR172a-1 inflorescences (Fig. 1D). This indicates that miRNA172 regulates AP2 expression at the translational level.

Expression of MIR172 with the 35S enhancer demonstrated the ability of MIR172 to regulate AP2 expression in planta when it is expressed from an exogenous promoter. Is miRNA172 normally present at the expected time during flower development? A modified in situ hybridization procedure showed that the antisense miRNA172 probe gave strong signals in stage 1 floral primordia (Fig. 3F). The signal persisted in all four floral whorls until stage 7, when miRNA172 appeared to be concentrated in the inner two floral whorls (Fig. 3H). The signal was unlikely to be a result of the miRNA precursor (fig. S2). The sense probe did not give any hybridization signals (Fig. 3, G and I). The presence of miRNA172 in developing flowers indicates that miRNA172 can regulate AP2 in floral patterning. In fact, the later accumulation of miRNA172 in the inner two whorls may cause AP2 protein to be concentrated in the outer two floral whorls, where AP2 acts to specify perianth identities.

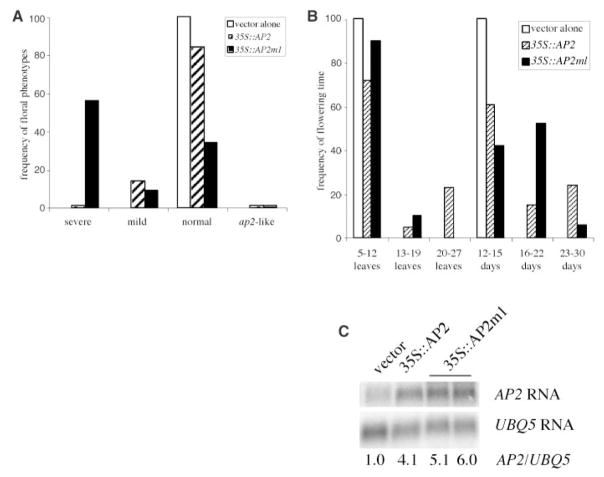

The ability of miRNA172 to repress AP2 expression in vivo and the presence of miRNA172 in the flower suggest that miRNA172 normally keeps AP2 expression level low during flower development. To assess the importance of this regulation in flower development and to determine whether this regulation is direct, I introduced wild-type AP2 cDNA or AP2m1, a mutant AP2 cDNA with six mismatches to miRNA172 (Fig. 1A), into wild-type plants and expressed them under the control of a 35S promoter. As a result, 100 and 82 independent transgenic plants for 35S::AP2 and 35S::AP2m1, respectively, were obtained. Dramatic differences were found in the severity and frequency of floral defects between the two transgenic T1 populations (Fig. 4A). About 60% of 35S::AP2m1 plants had flowers with an enlarged floral meristem surrounded by many whorls of staminoid organs or petals (Fig. 3, J and K). Some floral defects, such as the loss of floral determinacy and the transformation of stamens to petals, resemble those in ag severe loss-of-function mutants, which is consistent with the ability of AP2 to negatively regulate AG. Other floral defects, such as the enlargement of the floral meristem and the extreme excess of stamens, suggest that AP2 regulates other floral patterning genes. Alternatively, these phenotypes may have resulted from elevated AP2 expression and do not represent the natural functions of AP2. In contrast to 35S::AP2m1 plants, the majority of 35S::AP2 plants had normal flowers (Fig. 4A). Only a small number of 35S::AP2 plants showed mild floral defects (Fig. 3L). The 35S::AP2 plants with normal flowers had elevated AP2 RNA accumulation comparable to those in 35S::AP2m1 plants with severe floral defects (Fig. 4C and fig. S3). However, AP2 protein abundance was elevated in 35S::AP2m1 but not 35S::AP2 plants (Fig. 1D). The similarity in AP2 RNA abundance but difference in AP2 protein levels indicates that miRNA172 regulates AP2 expression at the translational level. Note that AP2 protein abundance in 35S::AP2m1 lines is similar to that in hen1 or dcl1 plants (Fig. 1D), although the hen1 or dcl1 floral defects are much weaker than those of 35S::AP2m1 plants. This may be a result of reduced accumulation of many miR-NAs, some of which may regulate targets that act antagonistically to AP2, in hen1 or dcl1 plants. Alternatively, some 35S::AP2m1 phenotypes may be a result of the exogenous promoter used in the study.

Fig. 4.

Analyses of 35S::AP2 and 35S::AP2m1 transgenic T1 lines. (A) The frequency of floral defects in 35S::AP2 and 35S::AP2m1 lines. (B) Flowering time as represented by the numbers of total leaves produced before flowering or the numbers of days it takes for the stem to reach 0.5 cm in length. (C) AP2 RNA accumulation in inflorescences from T1 transgenic plants containing the vector alone, 35S::AP2 (with normal flowers but flowers extremely late), or 35S::AP2m1 (with severe floral defects and flowers moderately late). Note that the tissues used were the same as the ones used in AP2 protein analysis shown in Fig. 1D. Numbers at the bottom indicate the relative amount of AP2 RNA in the various genotypes.

Many 35S::AP2 and 35S::AP2m1 plants also exhibited delayed floral transition (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, about a quarter of 35S::AP2 plants, although not exhibiting any floral phenotypes, were later flowering than 35S::AP2m1 plants, including those with severe floral defects (Fig. 4B). Although AP2 does not appear to function in floral transition, two closely related genes, At2g28550 (TOE1) and At5g60120 (TOE2), which also have a miRNA172 binding site, act as repressors of flowering (16). Given that 35S::AP2 and 35S::AP2m1 lines with moderately or severely delayed floral transition showed high levels of AP2 RNA (Fig. 4C and fig. S3) but only 35S::AP2m1 lines had high levels of AP2 protein (Fig. 1D), it is likely that the late-flowering phenotypes in 35S::AP2 and 35S::AP2m1 plants were caused by two distinct mechanisms. The increased abundance of AP2 protein in 35S::AP2m1 may allow AP2 to act through the TOE pathway to delay floral transition. On the other hand, the increased abundance of AP2 RNA in 35S::AP2 lines may compete with the TOE RNAs for miRNA172 regulation such that more TOE proteins accumulate and delay floral transition. Consistent with this hypothesis, 35S::MIR172a-1 rescues the late-flowering phenotype of 35S::AP2 plants (19).

In addition to disrupting the miRNA172 binding site, the AP2m1 mutation also introduced an amino acid substitution (Phe to Leu, Fig. 1). To evaluate whether the phenotypes of 35S::AP2m1 plants were caused by the amino acid change, I generated 35S::AP2m3 plants, which harbor a truly silent mutation in the miRNA172 binding site (Fig. 1). Analysis of 88 independent transgenic plants showed that 35S::AP2m3 had nearly identical phenotypes to those of 35S::AP2m1 (fig. S4).

During flower development, miRNA172 represses the expression of AP2. This regulation is likely crucial for the proper development of the reproductive organs and for the timely termination of floral stem cells. Furthermore, this regulation appears to be mediated by direct sequence complementarity between AP2 mRNA and miRNA172 and occurs primarily at the level of translation. MiRNA172-guided cleavage of AP2 mRNA may also occur at a low level, because potential cleavage products, presumably mediated by miRNA172, have been previously detected by rapid amplification of cDNA ends–polymerase chain reaction (9, 15). This and other studies show that plant miRNAs can regulate their target mRNAs through one or both mechanisms, translational inhibition and transcript cleavage.

Acknowledgments

I thank B. Krizek for the AP2 cDNA clone and for communicating unpublished results; T. Ito for the pMAT137 vector; J. Liu and W. Park for technical assistance; A. Singson for providing equipment; Z. Liu, D. Wagner, S. Poethig, and R. Kerstetter for helpful discussions; R. Kerstetter and R. Steward for comments on the manuscript; and NIH (R01 GM61146) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1088060/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S4

Table S1

References and Notes

- 1.Pasquinelli AE, Ruvkun G. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambros V. Cell. 2003;113:673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel B, Bartel DP. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:709. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen PH, Ambros V. Dev Biol. 1999;216:671. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinhart BJ, et al. Nature. 2000;403:901. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang G, Reinhart BJ, Bartel DP, Zamore PD. Genes Dev. 2003;17:49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Z, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC. Curr Biol. 2003;13:784. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llave C, Xie Z, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC. Science. 2002;297:2053. doi: 10.1126/science.1076311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasschau KD, et al. Dev Cell. 2003;4:205. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohmann JU, Weigel D. Dev Cell. 2002;2:135. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Meyerowitz EM. Mol Cell. 1999;3:349. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Liu J, Cheng Y, Jia D. Development. 2002;129:1085. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park W, Li J, Song R, Messing J, Chen X. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1484. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01017-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jofuku KD, den Boer BGW, Montagu MV, Okamuro JK. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1211. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM. Development. 1991;112:1. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aukerman M, Sakai H. Plant Cell. 15:2730. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodrich J, et al. Nature. 1997;386:44. doi: 10.1038/386044a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizukami T, Ma H. Cell. 1992;71:119. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90271-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X. unpublished data. [Google Scholar]