Abstract

Background

While the association between perceived discrimination and health has been investigated, little is known about whether and how neighborhood characteristics moderate this association.

Purpose

We situate discrimination in the housing context and use relative deprivation and social capital perspectives to fill the knowledge gap.

Methods

We applied multilevel logistic modeling to 9,842 adults in 830 neighborhoods in Philadelphia to examine three hypotheses.

Results

First, the detrimental effect of discrimination on self-reported health was underestimated without considering neighborhood features as moderators. The estimated coefficient (β) increased from approximately 0.02 to 1.84 or higher. Second, the negative association between discrimination and self-reported health was enhanced when individuals with discrimination experience lived in neighborhoods with higher housing values (β= 0.42). Third, the adverse association of discrimination with self-reported health was attenuated when people reporting discrimination resided in neighborhoods marked by higher income inequality (β= −4.34) and higher concentrations of single parent households with children (β= −0.03) and minorities (β= −0.01).

Conclusions

We not only confirmed the moderating roles of neighborhood characteristics, but also suggested that the relative deprivation and social capital perspectives could be used to understand how perceived housing discrimination affects self-reported health via neighborhood factors.

Keywords: Perceived discrimination, housing market, self-reported health, neighborhood effects

Introduction

Racial discrimination, in general, undermines minorities’ life chances by reducing access to socioeconomic opportunities and introducing mental stress to daily life, ultimately affecting health (1). Situating racial discrimination in housing markets refers to that one’s purchase or rental of housing is denied on the basis of race, ethnicity, or skin color (2), the consequence being that minorities disproportionately live in substandard neighborhoods. While several explanations have been proposed to understand why discrimination occurs across housing market (3–7), little is known about whether and how neighborhood factors are associated with the relationship between perceived discrimination and health. This study argues that racial discrimination in housing markets serves as a sorting process that leads minorities to reside in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods (e.g., high poverty rates) (8, 9), a relationship which has been found to adversely affect residents’ health outcomes (10, 11). Coupled with the adverse associations of racial discrimination with health, those who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods may undergo the joint influence of discrimination and neighborhood environment on health outcomes.

Recent literature has found that racial discrimination itself (12, 13) and neighborhood environment (10, 11) are associated with health. However, most literature was focused on the direct associations of racial discrimination and neighborhood characteristics with health and little is known about whether and how racial discrimination interacts with neighborhood environment to jointly affect health. That is, the question of how neighborhood environment “moderates” the relationship between perceived discrimination and health remains unanswered. The goal of this study is to fill this gap by answering the following questions: (a) Do the people with discrimination experience in housing markets exhibit worse health outcomes than those without the discrimination experience? (b) If yes, could the relationship between discrimination and health be moderated by neighborhood conditions? And (c) if the relationship could be moderated, what are the potential moderators? The next section will discuss why racial discrimination in housing markets may affect health and what the potential moderators are.

Perceived Housing Discrimination and Self-reported Health

Perceived discrimination is mainly focused on individuals’ experiences with discrimination in a range of social settings (14). Measuring perceived discrimination is based on the simplest definition of discrimination, which refers to the unequal treatment of persons or groups due to their race/ethnicity (15). Perceived discrimination is a common measure when studying how discriminatory experience affects health (16, 17) and it has been found to have an adverse relationship with health (13, 18). It should be noted that the empirical evidence seems to support a stronger relationship of perceived discrimination with mental health issues (e.g., anxiety and depression) than with physical health indicators (18–20). Among those health outcomes with mixed evidence, self-reported health may be the most divided measure. After reviewing 40 studies on the relationship between perceived discrimination and self-reported health, Paradies (19) found that half of them reported no relationship between perceived discrimination and self-reported health, whereas the other half suggested that perceived discrimination is detrimental to self-reported health. Because self-reported health (SRH hereafter) has been identified as a powerful predictor for diseases or mortality (21) and health researchers have attempted to investigate its determinants (22, 23), there is still a need to continue exploration of the relationship between discrimination and SRH.

When discriminatory experience is perceived in housing markets, several potential negative effects on health pertaining to this context should be noted. First, housing is one of the fundamental needs of life and provides a place where an individual or family spends most of their time. Discrimination in housing markets may force individuals to live in undesirable areas or homes. Substandard housing conditions have been found in association with the presence of cockroaches and rats, water leaks, poor ventilation, and exposure to harmful chemicals. These factors are predictive of various diseases (24, 25). Second, housing plays a critical role in linking an individual or a family to the society and neighborhood. Without fair housing opportunities, minorities may disproportionately live in an underserved neighborhood. In such a neighborhood, one’s life chances can be undermined such as through limited access to public services and facilities (26). As socioeconomic conditions are critical agents of disease (27), discrimination in housing markets may indirectly cause negative consequences on an individual’s health. Third, an individual’s self-esteem or self-perception can be, in part, attributed to housing (28), as decent housing in a stable neighborhood provides a sense of belonging and safety (29). Perceived discrimination in housing markets may increase psychological stress and eventually lead to poor overall health (30, 31). These mechanisms suggest that racial discrimination in housing markets may be both directly and indirectly related to individual health.

Neighborhood Characteristics as Moderators

In the US, residents in neighborhoods with high concentrations of minorities or people with low socioeconomic status are more likely to be exposed to social stressors and health risks (e.g., unemployment and pollution) than their counterparts in other types of neighborhoods (32). Evidence has suggested that these risk factors directly shape health outcomes and behaviors (11, 33). However, relatively few studies attempt to understand if neighborhood characteristics indirectly contribute to individual health, such as moderating the relationship between health outcomes and other covariates (34, 35). Specific to this study, little is known about whether the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH differs across neighborhoods. More explicitly, while discrimination in housing markets may affect where housing seekers eventually reside, to our knowledge, no study has attempted to understand if neighborhood characteristics moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. We argue that the adverse relationship of perceived discrimination with health is amplified when individuals with discrimination experience live in a socioeconomically affluent neighborhood. On the other hand, the negative impact of perceived discrimination on health is buffered when people who experienced discriminatory behaviors live in a neighborhood with high concentrations of minorities and disadvantaged groups. The following explanations outline our arguments.

One of the explanations for discrimination in housing markets is the concern about a decrease in value or quality of public services in a neighborhood (3). When real estate agents or landlords of rental properties treat housing-seekers unfairly due to their own prejudice or do not expect to gain maximal profits from housing-seekers, they may intentionally prevent their clients from residing in certain neighborhoods (36). This situation occurs particularly when a person who has experienced discriminatory behaviors seeks to live in a socioeconomically affluent neighborhood. When such a person ends up living in an affluent neighborhood, the sense of relative deprivation may further contribute to the relationship between discrimination and health. Specifically, the concept of relative deprivation suggests that individuals judge their status, broadly defined, by comparing themselves with others (37). In the circumstance of searching for housing, should people who experience discrimination come to realize that most of their neighbors did not share the same experience, they may feel inferior to their neighbors or relatively deprived due to the additional cost (i.e., being discriminated against) of living in a desirable neighborhood. Thus, the discriminatory experience in housing markets may be translated into resentment, which can further hinder one’s health. Similarly, it may be necessary at times for individuals to compete with their neighbors for limited resources. When individuals attribute the lack of resources to their discriminatory experience in housing markets, it may exacerbate anxiety or depression. This situation can also have negative impacts on health (37). By contrast, when applying this relative deprivation mechanism to those who perceived discrimination experience but did not live in affluent neighborhoods, the effect of perceived discrimination on health is less as individuals’ comparison with their neighbors may not generate the same sense of relative deprivation. In addition, it may be easier to compete for resources when living in a relatively disadvantaged neighborhood than in an affluent neighborhood for people with perceived discrimination in housing markets.

Social capital and cohesion is the other mechanism (38, 39) that explains why individuals with discrimination experience may have better health (particularly mental) while living in a neighborhood with more minorities or socially disadvantaged groups than if they lived in an affluent community. The core dimensions of social capital and cohesion include shared culture, sense of belonging, reciprocity, and mutual assistance/trust. Following this definition, social capital and cohesion is more directly relevant (or beneficial) to mental health than physical health (40), even though several scholars found that social capital and cohesion promote physical health (17, 41). Recently, it has been found that residents with homogeneous backgrounds are more likely to generate strong social capital and cohesion within a neighborhood (42). As minorities and individuals with low socioeconomic profiles are more likely to experience housing discrimination (3, 16), living close to one another or in the same neighborhood may enhance an interpersonal social network and mutual assistance/trust among neighbors, which in turn strengthens the social capital and cohesion of a neighborhood. When people live in such neighborhoods, social capital and cohesion protect them from the detrimental effects of discrimination and/or minimizes the effect of any low status stigma on health (43, 44). To reiterate, people with similar experiences tend to share similar culture, norms, attitudes, and values. This similarity (or homogeneity) among residents living in the same neighborhood provides both tangible and invisible support for coping with the effect of perceived discrimination in housing markets on health, such as providing comfort and sense of security, giving advice, and monetary help (45). These supportive relationships are more easily available for individuals who have perceived discrimination and are living in a neighborhood with more minorities or socially disadvantaged members, who are more likely to show empathy and help to negate the adverse effect of perceived discrimination on health.

Research Hypotheses

Based on the research questions and discussion above, we propose the following hypotheses. First, ceteris paribus, individuals who experienced discrimination in housing markets tend to have worse SRH than their counterparts without such experience. Second, the negative relationship between SRH and discrimination is more profound in those neighborhoods that are featured with a socioeconomically affluent profile, such as high housing values. Third, living in a neighborhood with high concentrations of minorities attenuates the adverse association of discrimination with SRH.

Data and Measures

The individual level data are from the 2008 Public Health Management Corporation’s (PHMC) Southeastern Household Survey conducted in the Philadelphia metropolitan area (46). The goal of the PHMC survey is to collect data on individual health behaviors, status, experience, and utilization of health care in the study region. Beyond the health-related information, the PHMC also gathers data on socioeconomic status, attitudes, and neighborhood social cohesion, which allows researchers or policymakers to address public health concerns. By comparing its findings with other data sources maintained by Federal agencies, the PHMC survey has been proven representative and reliable. For example, several health indicators or measures generated by the 2008 PHMC closely match the 2008 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data in Philadelphia (47), such as the breast cancer screening rate. Other socioeconomic status or racial composition indicators (e.g., unemployment or percentage of minorities) in the 2008 PHMC survey are also comparable with those reported by the American Community Survey. Further details about the PHMC data are available elsewhere (46). This study focused on respondents who answered the question of whether they experienced discrimination when getting housing in the survey (sample size = 9,842).

The dependent variable of this study, SRH (i.e., self-reported health, was a dichotomous variable derived from respondents’ ratings of their overall health. Respondents were asked to assess their general health as excellent, good, fair, or poor. Those who answered fair or poor were coded as 1, otherwise 0. This dichotomous approach to SRH has been commonly adopted in the literature that investigates the determinants of SRH (48).

The individual-level independent variables are categorized into five groups: perceived discrimination, health care system distrust, neighborhood social cohesion, health conditions, and sociodemographic features. The key explanatory variable is perceived discrimination when getting housing. Each respondent was asked to report whether s/he has ever experienced discrimination, been prevented from doing something, been hassled, or made to feel inferior when obtaining housing because of their race, ethnicity, or color. Those who reported perceived discrimination were coded as 1, otherwise 0. While this subjective discrimination measure is relatively crude, similar measures have been used in other studies or administered in surveys maintained by Federal agencies. Please see Paradies (19) for more detailed discussion.

The second independent variable is health care system distrust, a nine-item attitude scale developed by Shea et al (49). The main reason why this variable is considered is that distrust is found to affect health both directly and indirectly (17, 50). As such, including health care system distrust into this study will better assess the association between discrimination and SRH. The value of each item in the distrust scale ranges between 1 and 5, with higher values representing higher health care system distrust levels. The reliability of this scale has been reported elsewhere (49). In this study, we created one single composite distrust score based on each item’s factor loading (available upon request).

Neighborhood social cohesion was measured based on the following four questions: how likely people in the neighborhood are willing to help each other with routine activities; whether people in the neighborhood have worked together to improve the neighborhood; the degree to which the respondent agrees with the statements “I feel that I belong and am a part of my neighborhood,” and “Most people in my neighborhood can be trusted,” respectively. We used principal factor analysis to generate a neighborhood social cohesion index, with high values indicating better neighborhood social cohesion.

As for health conditions, we included three health concerns in the analysis – chronic diseases, high blood cholesterol, and depression. Respondents were asked if they have been diagnosed with any one of these issues by their physicians or other medical professionals. Those who answered yes were coded as 1, otherwise they were coded as 0. Note that the three health conditions include both physical and mental health issues and taking them into account provides strong evidence if SRH is negatively associated with perceived discrimination because these potential confounders are controlled.

The last group of individual explanatory variables includes sociodemographic features. Age was treated as a continuous variable, and income level was classified into quartiles, low (reference group), median-low, median-high, and high income. The original income variable in PHMC includes 19 income groups and the quartiles were created based on relative frequencies. Gender was a dichotomous variable with 1 being males, and 0 being females. Marital status was coded as 1 for those who were married or living with a partner and those with other statuses (e.g., single or divorced) were coded as 0. Educational attainment was originally divided into five categories: less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, and post-college. We used the category of less than high school as the reference group and then created four dummy variables in the analysis. Race/ethnicity was divided into four groups, including non-Hispanic White (reference group), non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other races. Three race/ethnicity dummy variables were used in this study. It should be noted that several recent studies on perceived discrimination included non-Hispanic White in the analysis because this measure of discrimination is subjective and non-Hispanic White have also reported racial discrimination experience in different social contexts, such as work place or medical system (51, 52). Therefore, it may not be appropriate to assume that non-Hispanic White respondents cannot perceive discriminatory behavior.

Regarding the neighborhood-level measures, we first defined neighborhoods with census tracts (n=830). While there is no agreement on how to define or operationalize a neighborhood in the literature, census tracts have commonly been used as a proxy of neighborhood (53). The American Community Survey (ACS) 2006–2010 is the data source for the following four neighborhood-level variables. Housing value was a factor score derived from three housing related indicators, namely median house value (factor loading=0.97), median gross rent (0.55), and median monthly mortgage (0.96). Housing value generally captures the socioeconomic profile of the population in a neighborhood and reflects the quality of public services. The second variable is the percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks, which measures the racial composition in a neighborhood. The third variable is the percentage of single parent households with children. As single-parent households with children have been found to be socioeconomically fragile (54), we used this variable to indicate the aggregation of disadvantaged groups. The last neighborhood-level variable is Gini index, a measure of income inequality ranging from 0 (completely equal) to 1 (completely unequal). It should be noted that the ACS uses the lowest value of an open-ended income category to calculate Gini index and this approach may slightly underestimate income inequality. Following Harling et al. (55), Gini index also measures structural inequality of a community and controlling for it further clarifies the effects of other neighborhood variables on health.

Methods

Generalized hierarchical linear modeling was applied to the data. In order to examine whether neighborhood features moderate the associations between perceived discrimination and SRH, we first concentrate on the associations of individual- and neighborhood-level covariates with SRH and then include the cross-level interactions in the analysis, which allows us to test all hypotheses. The statistical specification of the model that considers both individual- and neighborhood-level covariates can be expressed as follows:

, where ηij indicates the log odds of answering fair/poor SRH for the ith respondent in the jth neighborhood, ϕij is the probability of having fair/poor SRH for this specific respondent, γ00 is the fixed intercept, and u0j represents the random intercept across neighborhoods. γ0l is the coefficient for wlj (covariate l in the jth neighborhood), and βkj represents the coefficient for xijk (feature k of the ith respondent in the jth neighborhood). We first included only the individual covariates (x’s) into the analysis and then added the neighborhood variables (w’s) into the regression model. This model will help us to understand if the individual- and neighborhood-level variables explain why a person answered fair/poor health.

To investigate whether neighborhood features moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH, the interactions between neighborhood features and the discrimination experience are included in the analysis. More specifically, we examine whether or not the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH varies by the level of neighborhood features. Take the Gini index for example, its interaction with perceived discrimination can be express as below:

, where γdiscrimination, Gini is the coefficient for the interaction between one’s discrimination experience and the income inequality (Gini) in his/her residential neighborhood, and γ10 is the adjusted intercept. Extending this interaction term to other neighborhood features permits us to thoroughly test our hypotheses. We used Stata (version 12) to conduct the analysis.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table 1 and we tested for any significant difference in the variables between those who perceived discrimination and those who did not. Several key findings were summarized as follows: First, approximately 5 percent of the total respondents experienced discriminatory behaviors when getting housing. The proportion of respondents reporting fair/poor SRH was significantly higher among those with discrimination experience than among those without. Also, in contrast to those who did not experience housing discrimination, individuals who perceived discrimination reported higher levels of health care system distrust and poorer neighborhood social cohesion. Second, the proportions of those having chronic diseases or depression were higher among respondents with discrimination experience than those without. The difference in high blood cholesterol was relatively minimal. Third, compared to those without discrimination experience, people who perceived discrimination displayed the following sociodemographic characteristics: younger age, lower income level, less likely to receive a post-college degree, and more likely to be minority group members. Finally, respondents who perceived discrimination tended to live in the neighborhoods with lower housing values, higher concentrations of non-Hispanic Blacks and single parent households with children, and higher income inequality. The descriptive statistics suggest that experiencing housing discrimination may be associated with a range of social and health concerns at the individual level and that housing discrimination is related to segregation and aggregation of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables and Comparisons by Perceived Discrimination

| Total sample N=9842 |

With discrimination N=485 |

Without discrimination N=9357 |

Two-sample comparison |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable namea | Meanb | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean differencec |

| Individual level | |||||||

| Discrimination when getting housing (1=Yes, 0=No) |

0.049 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Poor/fair self-rated health (1=Yes, 0=No) |

0.214 | NA | 0.365 | NA | 0.204 | NA | 0.161 *** |

| Health care system distrustF | 0.000 | 0.917 | 0.619 | 0.869 | −0.036 | 0.908 | 0.655 *** |

| Neighborhood social cohesionF | 0.000 | 0.805 | −0.460 | 0.950 | 0.027 | 0.788 | −0.486 *** |

| Health conditions | |||||||

| Chronic disease (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.268 | NA | 0.395 | NA | 0.259 | NA | 0.136 *** |

| High blood cholesterol (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.298 | NA | 0.275 | NA | 0.299 | NA | −0.024 |

| Depression (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.137 | NA | 0.240 | NA | 0.131 | NA | 0.109 *** |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 52.379 | 16.220 | 46.592 | 13.312 | 52.620 | 16.258 | −6.028 *** |

| Gender (1=Male, 0=Female) | 0.323 | NA | 0.304 | NA | 0.324 | −0.020 | |

| Married or living w/ a partner (1=Yes, 0=No) |

0.548 | NA | 0.438 | NA | 0.555 | NA | −0.117 *** |

| Low income (1=Yes, 0=No) (Reference) |

0.231 | NA | 0.379 | NA | 0.225 | NA | 0.154 *** |

| Median low income (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.191 | NA | 0.225 | NA | 0.193 | NA | 0.032 † |

| Median high income (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.208 | NA | 0.161 | NA | 0.214 | NA | −0.053 ** |

| High income (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.370 | NA | 0.235 | NA | 0.368 | NA | −0.133 *** |

| Less than high school (1=Yes, 0=No) (Reference) |

0.075 | NA | 0.083 | NA | 0.074 | NA | 0.009 |

| High school graduate (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.322 | NA | 0.332 | NA | 0.321 | NA | 0.011 |

| Some college (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.201 | NA | 0.257 | NA | 0.198 | NA | 0.060 ** |

| College graduate (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.243 | NA | 0.214 | NA | 0.245 | NA | −0.031 |

| Post-college (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.160 | NA | 0.114 | NA | 0.163 | NA | −0.049 ** |

| White (1=Yes, 0=No) (Reference) | 0.673 | NA | 0.221 | NA | 0.698 | NA | −0.477 *** |

| Black (not Latino) (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.240 | NA | 0.573 | NA | 0.222 | NA | 0.350 *** |

| Latino (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.051 | NA | 0.126 | NA | 0.047 | NA | 0.079 *** |

| Other races (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.035 | NA | 0.080 | NA | 0.033 | NA | 0.047 *** |

| Neighborhood level (n=830) | |||||||

| Housing valueF | 0.000 | 0.977 | −0.560 | 0.788 | 0.034 | 0.976 | −0.594 *** |

| % Non-Hispanic Black | 24.744 | 32.604 | 47.586 | 36.360 | 23.375 | 31.841 | 24.211 *** |

| % Single parent household w/ children |

12.403 | 10.244 | 18.883 | 11.215 | 12.015 | 10.040 | 6.868 *** |

| Gini index | 0.412 | 0.067 | 0.432 | 0.069 | 0.411 | 0.067 | 0.021 *** |

Variables with F are constructs from factor analysis.

For binary variables, mean values denote the proportions of observations coded 1.

Significance levels were obtained by conducting two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and tests of proportions for binary variables.

p ≤ 0.001;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.1.

NA: Not Applicable because standard deviations are not meaninful for categorical variables.

Before conducting multilevel models, we examined the correlations among neighborhood variables (see Table 2) and found that housing value, percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks, and percentage of single parent households with children are moderately correlated (Pearson’s r over 0.6). However, these three neighborhood variables are only weakly related to the Gini index. To avoid multicollinearity, we paired the Gini index with only one of the three neighborhood variables in each model. As discussed previously, we chose this approach to control for structural inequality and better understand the relationships between other neighborhood measures and SRH.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients among Neighborhood-level Variables (n=830)

| Housing value |

% Non- Hispanic Black |

% Single parent household w/ children |

Gini index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing value | 1.000 | |||

| % Non-Hispanic Black | −0.613*** | 1.000 | ||

| % Single parent household w/ children | −0.702*** | 0.695*** | 1.000 | |

| Gini index | 0.038*** | 0.278*** | 0.250*** | 1.000 |

p≤0.001

We implemented a null model (i.e., without any independent variables) and found that roughly 8 percent of the variation in SRH can be attributed to neighborhoods (results not shown but available upon request). The multilevel modeling results are presented in Table 3 (numbers indicating odds ratios). While we reported odds ratios in Table 3, the original regression coefficients are available upon request. All models include individual level covariates and the differences across models are different sets of neighborhood level covariates and their interactions with perceived discrimination. We summarized the key findings as follows. First and foremost, our results indicate that without including the cross-level interactions between neighborhood characteristics and perceived discrimination, the main effect of perceived discrimination when getting housing may be underestimated or totally absent. Specifically, in Model 1a, those who perceived discrimination were only slightly more likely (odds ratio [OR]: 1.024; 95% confidence interval [CI]: (0.761, 1.379)) to report fair/poor SRH than those who did not. The main effect of perceived discrimination was not significant in Models 2a and 3a but it became significant in Models 2b (OR=6.312; 95% CI: (1.094, 36.405)) and 3b (OR=7.375; 95% CI: (1.281, 42.447)). The likelihood ratio tests (presented in the last row of Table 3) that compare the models without cross-level interactions with those with the interactions suggest that the latter were preferred in this study. The cross-level interactions provided nuanced insights into the relationships between perceived discrimination and SRH. In Model 1b, the interaction between housing value and discrimination suggested that, for those who reported perceived discrimination, the odds of reporting fair/poor SRH increased when housing values increased (OR=1.515; 95% CI: (1.047, 2.190)). Specifically, assuming respondents live in a neighborhood with average housing values and income inequality, the odds of reporting fair/poor SRH by respondents who perceived discrimination were approximately 44 percent higher than those without.1 By contrast, Models 2b (OR=0.988; 95% CI: (0.976, 0.996)) and 3b (OR=0.970; 95% CI: (0.944, 0.996)) indicated that people who perceived discrimination were less likely to report fair/poor SRH in a neighborhood with higher concentrations of non-Hispanic Blacks or single parent households with children.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios from Multilevel Logistic Regression of Self-reported Health (1=poor/fair, 0=good/excellent)a

| Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 3a | Model 3b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. (95% C.I.) | O.R. (95% C.I.) | O.R. (95% C.I.) | O.R. (95% C.I.) | O.R. (95% C.I.) | O.R. (95% C.I.) | |

| Individual level (n=9,842)b | ||||||

| Discrimination when getting housing (1=Yes, 0=No) | 1.024 (0.761, 1.379) | 8.653 (1.496, 50.065)* | 1.029 (0.764, 1.386) | 6.312 (1.094, 36.405)* | 1.022 (0.759, 1.376) | 7.375 (1.281, 42.447)* |

| Health care system distrustF | 1.150 (1.056, 1.253)*** | 1.149 (1.054, 1.251)** | 1.160 (1.066, 1.263)*** | 1.160 (1.065, 1.263)*** | 1.160 (1.065, 1.263)*** | 1.159 (1.064, 1.262)*** |

| Neighborhood social capitalF | 0.799 (0.727, 0.877)*** | 0.797 (0.726, 0.876)*** | 0.794 (0.723, 0.872)*** | 0.793 (0.722, 0.871)*** | 0.800 (0.728, 0.880)*** | 0.799 (0.727, 0.878)*** |

| Health conditions | ||||||

| Chronic disease (1=Yes, 0=No) | 5.145 (4.411, 6.001)*** | 5.155 (4.418, 6.015)*** | 5.172 (4.434, 6.032)*** | 5.189 (4.447, 6.054)*** | 5.158 (4.422, 6.016)*** | 5.173 (4.433, 6.035)*** |

| High blood cholesterol (1=Yes, 0=No) | 1.512 (1.286, 1.778)*** | 1.518 (1.291, 1.785)*** | 1.510 (1.285, 1.775)*** | 1.513 (1.287, 1.779)*** | 1.508 (1.283, 1.773)*** | 1.515 (1.288, 1.781)*** |

| Depression (1=Yes, 0=No) | 2.335 (1.936, 2.815)*** | 2.344 (1.943, 2.828)*** | 2.352 (1.951, 2.835)*** | 2.364 (1.960, 2.851)*** | 2.344 (1.944, 2.826)*** | 2.356 (1.953, 2.841)*** |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 1.015 (1.010, 1.021)*** | 1.016 (1.010, 1.021)*** | 1.015 (1.009, 1.020)*** | 1.015 (1.010, 1.021)*** | 1.015 (1.010, 1.021)*** | 1.015 (1.010, 1.021)*** |

| Gender (1=Male, 0=Female) | 1.257 (1.070, 1.477)** | 1.262 (1.074, 1.482)** | 1.260 (1.073, 1.481)** | 1.272 (1.083, 1.495)** | 1.263 (1.075, 1.484)** | 1.267 (1.078, 1.489)** |

| Married or living w/ a partner (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.814 (0.693, 0.957)* | 0.817 (0.695, 0.959)* | 0.800 (0.682, 0.940)** | 0.804 (0.685, 0.944)** | 0.800 (0.681, 0.939)** | 0.803 (0.684, 0.943)** |

| Low income (1=Yes, 0=No) (Reference) | ||||||

| Median low income (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.498 (0.402, 0.616)*** | 0.497 (0.402, 0.616)*** | 0.494 (0.399, 0.611)*** | 0.501 (0.405, 0.620)*** | 0.497 (0.402, 0.616)*** | 0.498 (0.402, 0.616)*** |

| Median high income (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.402 (0.315, 0.511)*** | 0.400 (0.314, 0.510)*** | 0.393 (0.309, 0.500)*** | 0.394 (0.310, 0.502)*** | 0.399 (0.313, 0.508)*** | 0.398 (0.312, 0.507)*** |

| High income (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.511 (0.413, 0.633)*** | 0.512 (0.414, 0.634)*** | 0.491 (0.397, 0.606)*** | 0.495 (0.401, 0.612)*** | 0.498 (0.402, 0.615)*** | 0.498 (0.403, 0.616)*** |

| Less than high school (1=Yes, 0=No) (Reference) | ||||||

| High school graduate (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.654 (0.502, 0.854)** | 0.662 (0.507, 0.864)** | 0.643 (0.493, 0.838)*** | 0.655 (0.502, 0.855)** | 0.654 (0.501, 0.853)** | 0.660 (0.506, 0.861)** |

| Some college (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.491 (0.366, 0.657)*** | 0.493 (0.368, 0.662)*** | 0.471 (0.352, 0.630)*** | 0.478 (0.357, 0.640)*** | 0.487 (0.363, 0.653)*** | 0.490 (0.366, 0.658)*** |

| College graduate (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.380 (0.280, 0.515)*** | 0.388 (0.286, 0.527)*** | 0.354 (0.262, 0.479)*** | 0.366 (0.270, 0.495)*** | 0.372 (0.274, 0.504)*** | 0.380 (0.280, 0.515)*** |

| Post-college (1=Yes, 0=No) | 0.296 (0.210, 0.417)*** | 0.296 (0.210, 0.417)*** | 0.270 (0.193, 0.379)*** | 0.272 (0.194, 0.381)*** | 0.287 (0.204, 0.403)*** | 0.287 (0.204, 0.404)*** |

| White (1=Yes, 0=No) (Reference) | ||||||

| Black (not Latino) (1=Yes, 0=No) | 1.570 (1.284, 1.921)*** | 1.543 (1.261, 1.888)*** | 1.534 (1.205, 1.952)*** | 1.482 (1.164, 1.887)*** | 1.624 (1.330, 1.984)*** | 1.585 (1.297, 1.938)*** |

| Latino (1=Yes, 0=No) | 1.553 (1.110, 2.172)** | 1.531 (1.095, 2.141)* | 1.681 (1.208, 2.338)** | 1.635 (1.173, 2.278)** | 1.572 (1.121, 2.203)** | 1.559 (1.113, 2.183)** |

| Other races (1=Yes, 0=No) | 1.787 (1.213, 2.632)** | 1.744 (1.183, 2.571)** | 1.776 (1.200, 2.629)** | 1.717 (1.158, 2.545)** | 1.837 (1.248, 2.703)** | 1.783 (1.209, 2.629)** |

| Neighborhood level | ||||||

| Housing valueF | 0.826 (0.746, 0.916)*** | 0.804 (0.724, 0.893)*** | ||||

| % Non-Hispanic Black | 1.004 (1.000, 1.007)*** | 1.005 (1.002, 1.008)*** | ||||

| % Single parent household w/ children | 1.013 (1.005, 1.022)*** | 1.016 (1.007, 1.025)*** | ||||

| Gini index | 0.846 (0.269, 2.661) | 1.281 (0.387, 4.236) | 0.531 (0.166, 1.696)*** | 0.689 (0.205, 2.313)*** | 0.463 (0.143, 1.497)** | 0.624 (0.183, 2.127)*** |

| Cross-level interactions | ||||||

| Housing value * discrimination | 1.515 (1.047, 2.190)* | |||||

| % Non-Hispanic Black * discrimination | 0.988 (0.979, 0.996)*** | |||||

| % Single parent household w/ children * discrimination | 0.970 (0.944, 0.996)*** | |||||

| Gini index * discrimination | 0.013 (0.000, 0.726)* | 0.058 (0.001, 3.842)*** | 0.041 (0.001, 2.829)* | |||

| Likelihood-ratio test comparing model “a” with model “b” | N.A. | 10.46** | N.A. | 13.78*** | N.A. | 10.50** |

p≤0.001***,

p≤0.01**,

p≤0.05*,

F indicates that the variable was constructed with factor analysis. Also, in contrast to model a, model b includes cross-level interaction terms.

Gini index was included in all models. Models 1a, 2a, and 3a consider housing values, % non-Hispanic blacks, and % single parent households with children, respectively. Models 1b, 2b, and 3b extended models 1a, 2a, and 3a by considering the interaction between the neighborhood factor and discrimination.

Among individuals answering whether they perceived housing discrimination, 2,077 reported poor/fair health and 7,737 reported good/excellent health.

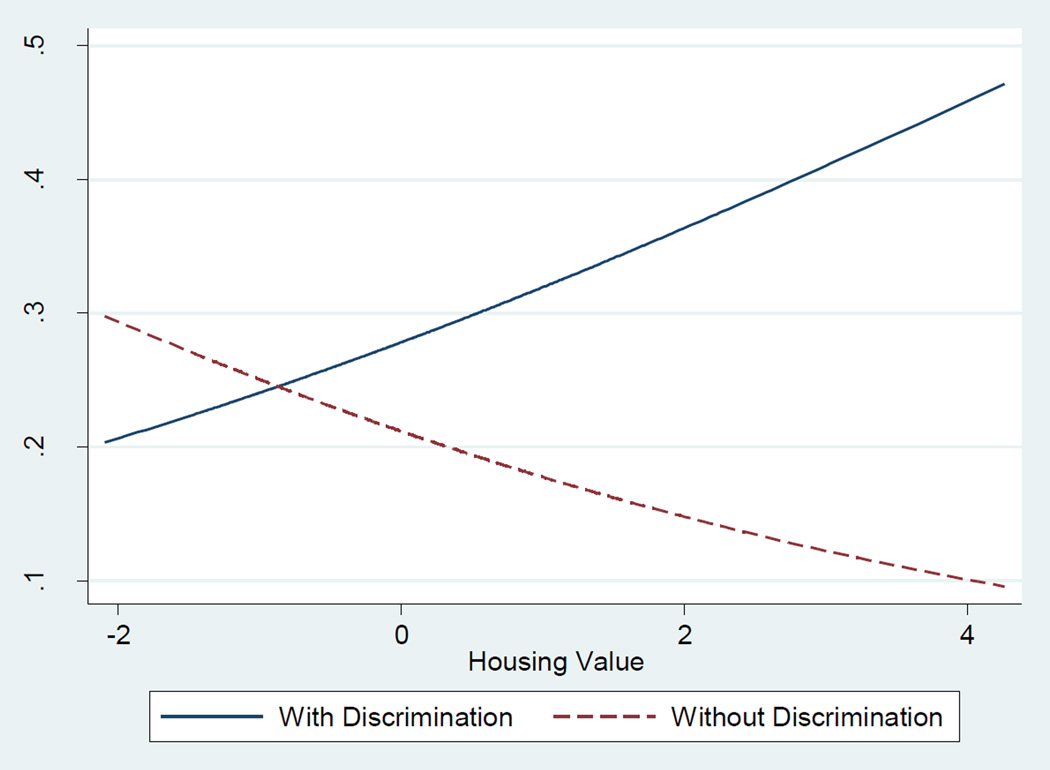

To better illustrate the effects of interactions between perceived discrimination and neighborhood characteristics, we calculated predicted marginal probabilities of reporting fair/poor SRH based on Models 1b, 2b, and 3b. More specifically, the marginal probability was based on the reference groups of the categorical variables (e.g., female, low income, and less than high school) and the sample means of continuous variables (e.g., 52.379 year-old, and Gini index of 0.412). Figure 1 shows how the predicted probability of reporting fair/poor SRH changed over the possible housing values in this study. Ceteris paribusthe probability of reporting fair/poor SRH was lower among individuals with discrimination experience than those without when the housing value is lower than −1. With the increase in housing value, the probability decreased from roughly 0.3 to 0.1 for those without any discrimination experience, whereas the probability soared from 0.2 to almost 0.5 for those who perceived discrimination when getting housing.

Figure 1.

Predicted Marginal Probabilities of Reporting Poor/Fair Self-reported Health by Discrimination across Housing Values (both lines are based on Model 1b)a

a. Compared to Model “1a”, Model “1b” includes an interaction (cross-level) term and the two lines in the figure are both based on Model 1b. The solid line indicates the marginal probability for people with perceived discrimination and the dash line shows the marginal probability for people without discrimination experience.

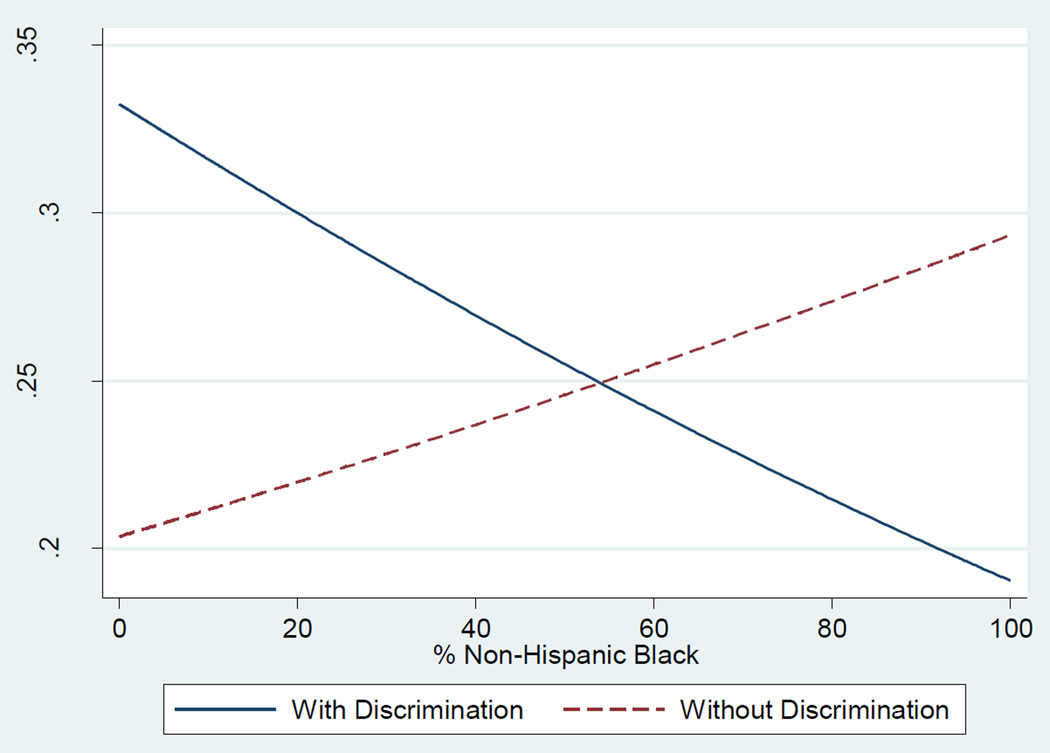

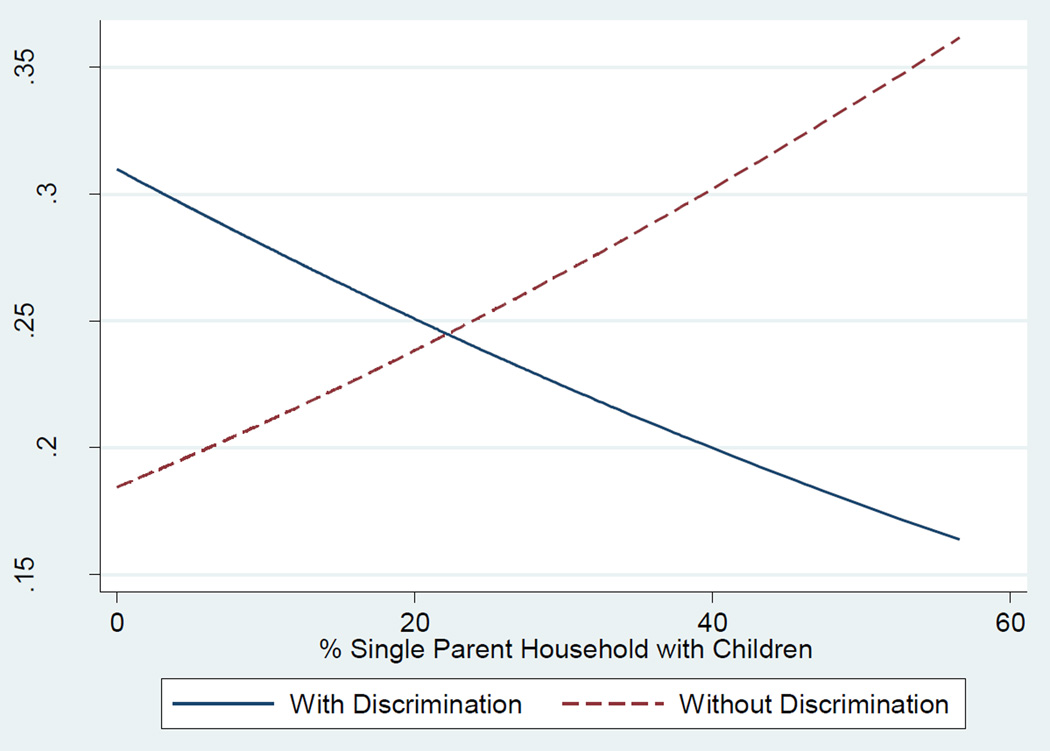

Figure 2 demonstrates a pattern that is similar to Figure 1. Assuming other things are equal, the probability of reporting fair/poor SRH for individuals who experienced discriminatory behaviors in housing markets was 0.34 when they lived in a neighborhood without any non-Hispanic Black residents. The probability dropped to slightly below 0.2 when a neighborhood has only non-Hispanic Black residents. On the other hand, for those without discrimination experience, the probability of reporting fair/poor SRH ranged from 0.2 to 0.3 and rises with the increase in the percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks in a neighborhood. Furthermore, Figure 3 tells a similar story in that living in a neighborhood with higher concentrations of single parent households with children lowers the probability of reporting fair/poor SRH for those who perceived discrimination (from 0.31 to approximately 0.16). These figures suggested that the association between perceived discrimination and SRH depends on the neighborhood level characteristics. Without putting individuals into context, the detrimental effect of perceived discrimination on health may be masked.

Figure 2.

Predicted Marginal Probabilities of Reporting Poor/Fair Self-reported Health by Discrimination across % Non-Hispanic Blacks (both lines are based on Model 2b)a

a. Compared to Model “2a”, Model “2b” includes an interaction (cross-level) term and the two lines in the figure are both based on Model 2b. The solid line indicates the marginal probability for people with perceived discrimination and the dash line shows the marginal probability for people without discrimination experience.

Figure 3.

Predicted Marginal Probabilities of Reporting Poor/Fair Self-reported Health by Discrimination across % Single Parent with Children (both lines are based on Model 3b)a

a. Compared to Model “3a”, Model “3b” includes an interaction (cross-level) term and the two lines in the figure are both based on Model 3b. The solid line indicates the marginal probability for people with perceived discrimination and the dash line shows the marginal probability for people without discrimination experience.

Second, in addition to perceived discrimination, health care system distrust and neighborhood social cohesion were found to be associated with SRH. Every one unit increase in health care system distrust was associated with roughly a 15 percent increase in the odds of reporting fair/poor SRH. By contrast, a one unit increase in one’s neighborhood social cohesion was related to almost a 20 percent decrease in the odds. These relationships of health care system distrust and neighborhood social cohesion with SRH were fairly stable across models and the inclusions of cross-level interactions barely altered the estimates.

Third, unsurprisingly, all health condition variables were positively associated with the odds of reporting fair/poor SRH and their associations were similar regardless of neighborhood level covariates. It should be noted that taking health conditions into account did not alter the statistically significant relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. Fourth, as for sociodemographic covariates, our findings echoed the literature (17, 21, 48). For example, males were found to have consistently higher probabilities of reporting poor/fair SRH than females. Respondents who are married or live with a partner were less likely to report fair/poor SRH. Respondents with high income levels or educational attainments were also less likely to report fair/poor SRH than their counterparts in the low income category or without a high school diploma. In contrast to non-Hispanic white, minority group members were at least 50 percent more likely to have fair/poor SRH. These patterns hold across all neighborhood factors and the predicted marginal probabilities for these individual characteristics are available upon request from the authors.

Fifth, with respect to neighborhood level covariates, we did not find a significant relationship between income inequality and SRH in most models. However, in general, residents in neighborhoods featured with high housing values and low concentrations of non-Hispanic Black or single parent households with children tended to report better SRH than those in neighborhoods with low housing values and high percentages of non-Hispanic Black or single parent households with children. It should be noted that these relationships were the main relationships between neighborhood characteristics and SRH (see Models 1a, 2a, and 3a) and, similar to the findings for the individual level covariates, taking interaction terms into consideration did not change the findings (see Models 1b, 2b, and 3b). The effects of the interactions between these neighborhood covariates and perceived discrimination on SRH were discussed previously.

Discussion and Conclusions

We concisely examined the three hypotheses with the results above. Our first hypothesis indicates that individuals who experienced housing discrimination have worse SRH than those who did not. Our analytic results not only confirmed this hypothesis but also suggested that the detrimental effect of perceived discrimination on SRH could be overlooked. Explicitly, the odds of reporting fair/poor SRH for respondents who perceived discrimination were approximately 2 percent higher than those without such experience; however, after considering cross-level interactions between perceived discrimination and neighborhood characteristics in the analysis, the odds increased roughly 44 percent in favor of reporting fair/poor SRH by respondents who perceived discrimination. Furthermore, as Figure 1 shows, the probability of reporting fair/poor SRH rises with the increase in housing values among individuals experiencing discrimination. Specifically, the probability of having fair/poor SRH among discriminated respondents was roughly 0.2 in the neighborhood with the lowest housing value but the figure increased to almost 0.5 in the neighborhood with the highest housing value, which bolsters our second hypothesis. Lastly, the findings from Figures 2 and 3 support the third hypothesis that living in a neighborhood with high concentrations of minorities or socioeconomically disadvantaged groups attenuates the adverse association of discrimination with SRH.

As argued in this study, neighborhood characteristics moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH through relative deprivation (37) and social capital (38, 43) mechanisms. Housing discrimination serves as a sorting process to segregate minority (or socioeconomically disadvantaged) group members from the dominant racial (or affluent) group (3, 6) and individuals who perceived this discrimination were more likely to live in substandard neighborhoods (as our Table 1 shows). Nonetheless, our relative deprivation mechanism argues that when individuals who perceived discrimination and resided in socioeconomically affluent neighborhoods, they may feel inferior to their neighbors or relatively deprived of their basic needs, which amplifies the detrimental effect of perceived discrimination on SRH. When individuals who perceived discrimination live in a neighborhood marked by high concentrations of socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, the sense of relative deprivation may be minimized. Living in such neighborhoods may make the opportunity to gain resources more equal among residents, which attenuates the association of perceived discrimination with SRH. The social capital mechanism, on the other hand, suggests that the adverse relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH may be buffered when people with discrimination experience live in a neighborhood where the residents tend to empathize with discrimination or provide support to cope with discrimination (38). Except for income inequality in a neighborhood, the cross-level interactions between other neighborhood characteristics and individual perceived discrimination seem to offer support for the two mechanisms above. It should be emphasized that even when including individual neighborhood social cohesion, a proxy for individual social capital (17) in the analysis, we still found that neighborhood characteristics moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. This is an important finding as it suggests that the moderating effects of neighborhood factors are independent of other individual characteristics.

In addition to the major findings above, we found that individuals who reported perceived housing discrimination were different from their counterparts without discrimination experience along with a range of individual and neighborhood level dimensions. While only five percent of the respondents reported discrimination when looking for housing, they tended to have a poor socioeconomic profile and their neighborhoods of residence had low housing values and high concentrations of minorities and disadvantaged groups. The distinctive features of discriminated individuals indicate that while discrimination has become less identifiable since the Civil Rights Era (12), it remains a social problem and may lead to health disparities across social groups (13, 15). We would like to emphasize that our findings are fairly robust, particularly when taking the sample size of those who reported discrimination into account. Specifically, only five percent of the respondents reported discrimination, which means that the variation in housing discrimination is small in our data and this variable may not account for much of the variation in SRH. However, our analytic results were found to support our hypotheses, indicating that perceived housing discrimination interacts with neighborhood factors to jointly affect SRH despite the relatively small variation within our data.

This study directly speaks to the literature on how disadvantaged populations (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities and individuals from low socioeconomic status background) manage to obtain/maintain good health. For example, living in an affluent neighborhood may not necessarily protect individuals from the negative impact of discrimination, which is parallel to the suggestion that the protective factors for disadvantaged groups may not be the same with those for affluent groups (56). In addition, this study, to some extent, bolsters a recent study reporting that social support buffers the adverse effect of discrimination on stress (57). The findings of this study highlight the need to identify the barriers and facilitators of health for different social groups.

This study has several limitations. First, the research design is cross-sectional and only focused on the Philadelphia metropolitan area. The causal relationships between SRH and independent covariates could not be determined and one should be cautious to generalize our findings to other populations. Second, the measure of housing discrimination is subjective. While the subjective measures have been used in research (18, 19, 52), future effort is warranted to explore whether different discrimination measures generate different findings. Third, we use census tracts to define neighborhoods and assume that individual health is only affected by the characteristics of the neighborhood of residence. Due to the data limitation, we could not create an activity space for each individual to more accurately capture neighborhood effects (53). Finally, the theoretical mechanisms proposed in this study are not exhaustive and may not be thoroughly measured or captured with the PHMC survey and census data.

The limitations above could, however, be translated into future research directions. First, to fully explore the relative deprivation and social capital mechanisms, it is crucial to collect detailed information on the social dynamics among residents in a neighborhood (e.g., social networks). A longitudinal research design will help clarify the causality between discrimination and health. Second, future research should focus on how individuals cope with the stress caused by housing discrimination and explore whether the coping mechanisms differ by the social context where discrimination is perceived (e.g., health care system and work place). Finally, as individuals are not confined to their residential neighborhoods, it remains underexplored whether (and if so, how) other environments to which individuals are exposed (e.g., immediate adjacent neighborhoods) contribute to the relationship between perceived discrimination and health. More attention to this issue is needed to thoroughly investigate how neighborhood factors “get under the skin” (58).

The analytic results offered several implications that can be used to ameliorate the adverse effect of perceived housing discrimination on health. First, the moderating roles of neighborhood characteristics underscore the importance of developing neighborhoods that are racially and socioeconomically integrated. As shown above in this study, the probability of reporting fair/poor SRH for respondents who reported discrimination intersects with that for individuals who did not report discrimination. Where the two probabilities meet may indicate the optimal levels of neighborhood characteristics that benefit all residents in a neighborhood, regardless of the status of perceived discrimination. In contrast to living in an affluent neighborhood, residing in an integrated neighborhood may indicate a low level of relative deprivation, which buffers the effect of perceived discrimination. Second, while housing discrimination is relatively rare in the study area, its adverse effect on SRH remains significant. To minimize housing discrimination, all the information related to buying or renting a property should be as transparent as possible, which could help reduce “perceived” discrimination. Third, following the two mechanisms proposed in this study, strengthening social capital or cohesion of a neighborhood helps moderate the negative impact of perceived discrimination on health. Providing a public space to residents (e.g., community gardens) or organizing community activities (e.g., garage sales) should facilitate mutual understanding among residents of different backgrounds, which develops social networks where social support is embedded (42).

In sum, using the data from the Philadelphia metropolitan area, this study found that the relationship between perceived discrimination when searching for housing and SRH is moderated by neighborhood characteristics, which has not been done in previous literature. The adverse impact of perceived discrimination on SRH is more profound in socioeconomically affluent neighborhoods but is tempered in neighborhoods with high concentrations of minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. Without taking the moderating roles of neighborhood characteristics into account, the detrimental association of perceived discrimination with SRH is underestimated or completely absent. Our findings provide nuanced insight to the literature on discrimination and health.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge assistance provided by the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany, State University of New York, which receives core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; R24-HD04494309).

Footnotes

COI and Ethical adherence statement:

All authors of this manuscript entitled “Perceived Housing Discrimination and Self-rated Health: How do Neighborhood Features Matter?” declare no conflict of interests and adhere to the following principles: 1. All authors approved the submission to Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2. All authors made significant intellectual contributions to this manuscript. 3. The work submitted to Annals of Behavioral Medicine is original and has not been published elsewhere and is not currently under consideration for publication by any other journals. Appropriate citations are used to acknowledge the contribution of previous research to this manuscript. 4. Should any of the statements cease to be true, the authors should notify Annals of Behavioral Medicine and withdraw the submission immediately.

exp(βDiscrimination * Disccrimination + βDiscrimination × Housing Value * Disccrimination * Housing Value + βDiscrimination × Gini Index * Disccrimination * Gini Index) = exp (2.158 + 0.415 × 0 − 4.359 × 0.412) = 1.436

Contributor Information

Tse-Chuan Yang, Department of Sociology, Center for Social and Demographic Analysis, University at Albany, SUNY

Danhong Chen, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, University of Arkansas

Kiwoong Park, Department of Sociology, Center for Social and Demographic Analysis, University at Albany, SUNY.

References

- 1.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and Health II: A Needed Research Agenda for Effective Interventions. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0002764213487341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ondrich J, Ross SL, Yinger J. How common is housing discrimination? Improving on traditional measures. Journal of Urban Economics. 2000;47:470–500. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yinger J. Measuring racial discrimination with fair housing audits: Caught in the act. The American Economic Review. 1986:881–893. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanson A, Hawley Z. Where does racial discrimination occur? An experimental analysis across neighborhood and housing unit characteristics. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 2014;44:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wienk RE. Measuring Racial Discrimination in American Housing Markets: The Housing Market Practices Survey. 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yinger J. Closed doors, opportunities lost: The continuing costs of housing discrimination. Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roscigno VJ, Karafin DL, Tester G. The complexities and processes of racial housing discrimination. Social Problems. 2009;56:49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logan JR. Growth, politics, and the stratification of places. American Journal of Sociology. 1978:404–416. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adelman RM. Neighborhood opportunities, race, and class: The Black middle class and residential segregation. City & Community. 2004;3:43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:125–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuman H, Steeh C, Bobo L, Krysan M. Racial attitudes in America: Trends and interpretations (Revised edition.) Harvard University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of health and social behavior. 1999:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, Yang T-C. The pathways from perceived discrimination to self-rated health: An investigation of the roles of distrust, social capital, and health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;104:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. international Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, et al. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prus SG. Comparing social determinants of self-rated health across the United States and Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexopoulos EC, Geitona M. Self-rated health: inequalities and potential determinants. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2009;6:2456–2469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6092456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northridge J, Ramirez OF, Stingone JA. The role of housing type and housing quality in urban children with asthma. Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs DE, Wilson J, Dixon SL, Smith J, Evens A. The relationship of housing and population health: A 30-year retrospective analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009;117:597. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bratt RG, Stone ME, Hartman C. Why a right to housing is needed and makes sense: Editors’ introduction. In: Tight JR, Mueller EJ, editors. Affordable Housing Reader. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of health and social behavior. 1995:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schorr AL. In: Slums and Social Insecurity. E. a. W. US Department of Health, editor. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rakoff RM. Ideology in Everyday Life:-The Meaning of the House. Politics & Society. 1977;7:85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollack CE, Griffin BA, Lynch J. Housing affordability and health among homeowners and renters. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010;39:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bentley R, Baker E, Mason K. Cumulative exposure to poor housing affordability and its association with mental health in men and women. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2012;66:761–766. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morello-Frosch R, Zuk M, Jerrett M, Shamasunder B, Kyle AD. Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: implications for policy. Health affairs. 2011;30:879–887. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2001;55:111–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews SA, Yang T-C. Exploring the role of the built and social neighborhood environment in moderating stress and health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39:170–183. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boardman JD. Stress and physical health: the role of neighborhoods as mediating and moderating mechanisms. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:2473–2483. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Card D, Mas A, Rothstein J. Tipping and the Dynamics of Segregation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2008;123:177–218. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jencks C, Mayer SE. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighbourhood. In: Lynn LEJ, McGeary MGH, editors. Inner-city poverty in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. pp. 111–186. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stafford M, Bécares L, Nazroo J. Ethnicity and Integration. Springer; 2010. Racial discrimination and health: exploring the possible protective effects of ethnic density; pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rios R, Aiken LS, Zautra AJ. Neighborhood contexts and the mediating role of neighborhood social cohesion on health and psychological distress among Hispanic and non-Hispanic residents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43:50–61. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKenzie K, Harpham T. Social capital and mental health. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Kim D. Social capital and health. Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Putnam RD. E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian political studies. 2007;30:137–174. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bécares L, Nazroo J, Stafford M. The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health & place. 2009;15:700–708. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bécares L, Cormack D, Harris R. Ethnic density and area deprivation: Neighbourhood effects on Māori health and racial discrimination in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of immigrant health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.PHMC. Public Health Management Corporation's Southeastern Household Survey. Philadelphia: PHMC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.CDC. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of health and social behavior. 1997:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shea J, Micco E, Dean L, et al. Development of a Revised Health Care System Distrust Scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:727–732. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0575-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armstrong K, Rose A, Peters N, et al. Distrust of the Health Care System and Self-Reported Health in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:292–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirsh E, Lyons CJ. Perceiving discrimination on the job: Legal consciousness, workplace context, and the construction of race discrimination. Law & Society Review. 2010;44:269–298. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matthews SA, Yang T-C. Spatial Polygamy and Contextual Exposures (SPACEs): Promoting Activity Space Approaches in Research on Place And Health. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0002764213487345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacLanahan SS. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harling G, Subramanian S, Bärnighausen T, Kawachi I. Income inequality and sexually transmitted in the United States: Who bears the burden? Social Science & Medicine. 2014;102:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen E, Miller GE. Socioeconomic status and health: mediating and moderating factors. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mossakowski KN, Zhang W. Does Social Support Buffer the Stress of Discrimination and Reduce Psychological Distress Among Asian Americans? Social Psychology Quarterly. 2014 0190272514534271. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor SE, Repetti RL, Seeman T. Health psychology: what is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:411–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]