Abstract

Under normal conditions, the function of catalytically active proteases is regulated, in part, by their endogenous inhibitors, and any change in the synthesis and/or function of a protease or its endogenous inhibitors may result in inappropriate protease activity. Altered proteolysis as a result of an imbalance between active proteases and their endogenous inhibitors can occur during normal aging, and such changes have also been associated with multiple neuronal diseases, including Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), rare heritable neurodegenerative disorders, ischemia, some forms of epilepsy, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). One of the most extensively studied endogenous inhibitor is the cysteine-protease inhibitor cystatin C (CysC). Changes in the expression and secretion of CysC in the brain have been described in various neurological disorders and in animal models of neurodegeneration, underscoring a role for CysC in these conditions. In the brain, multiple in vitro and in vivo findings have demonstrated that CysC plays protective roles via pathways that depend upon the inhibition of endosomal-lysosomal pathway cysteine proteases, such as cathepsin B (Cat B), via the induction of cellular autophagy, via the induction of cell proliferation, or via the inhibition of amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation. We review the data demonstrating the protective roles of CysC under conditions of neuronal challenge and the protective pathways induced by CysC under various conditions. Beyond highlighting the essential role that balanced proteolytic activity plays in supporting normal brain aging, these findings suggest that CysC is a therapeutic candidate that can potentially prevent brain damage and neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Cystatin C, Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral amyloidosis, amyloid, Aβ, neurodegeneration

INTRODUCTION

CysC, also known as γ-trace, is a small molecular weight (~14 kDa) basic protein (Hochwald et al., 1967) belonging to the cystatin type 2 superfamily of evolutionarily well-conserved cysteine-protease inhibitors (Barrett, 1986). In humans, CysC was originally identified in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but has subsequently been found in all other mammalian body fluids and tissues (Bobek and Levine, 1992; Turk et al., 2008). Highlighting important roles for CysC in the brain, CysC is particularly abundant in brain tissue (Hakansson et al., 1996) were it is expressed by neurons, astrocytes, endothelial, and microglial cells (Miyake et al., 1996; Palm et al., 1995; Yasuhara et al., 1993). CysC is thought to be an important endogenous inhibitor of cysteine protease activity in part because of its potent in vitro inhibition of multiple cathepsins, including the cysteine-proteases cathepsin (Cat) B, Cat H, Cat K, Cat L, and Cat S [reviewed in (Bernstein et al., 1996; Turk et al., 2008)]. Cathepsins as a group are cysteine-, aspartyl-, and serine-proteinases that are predominantly found and active within the acidic endosomal-lysosomal system, although they are not restricted exclusively to these compartments [reviewed in (Turk et al., 2000)]. Cathepsins differ in evolutionary history, structure, substrate-specificity, and biochemical characteristics and are required for homeostatic protein turnover as well as regulated proteolysis [reviewed in (Turk et al., 2000)]. CysC itself is a target of proteolysis (Rider et al., 1996; Rudensky et al., 1991), and is inactivated through proteolytic degradation by the aspartyl-protease Cat D and the serine-protease elastase (Abrahamson et al., 1991; Lenarcic et al., 1991).

The primary structure of CysC in humans is a 120 amino acids protein preceded by a 26 amino acids amino-terminal secretory signal (Turk et al., 1997; Turk and Bode, 1991). This primary sequence is indicative of a secreted protein, and accordingly, most newly synthesized CysC is secreted from a cell (Barka et al., 1992; Chapman et al., 1990; Paraoan et al., 2001; Tavera et al., 1992; Wei et al., 1998; Zucker-Franklin et al., 1987). Cell surface CysC has been demonstrated in various cells (Calkins et al., 1998; Sastre et al., 2004; Taupin et al., 2000), consistent with it being both a secreted protein as well as one that can be internalized into a cell via endocytosis (Ekstrom et al., 2008; Kolodziejczyk et al., 2010; Merz et al., 1997). Endogenously produced CysC has been found in endosomal-lysosomal cellular compartments, where it was shown to inhibit cathepsin activities within the lysosomal system (Pierre and Mellman, 1998). Exogenous CysC added to cell-culture media is internalized (Ekstrom et al., 2008; Kolodziejczyk et al., 2010; Merz et al., 1997), and internalized CysC co-localized with Cat D in lysosomes (Wallin et al., 2013). Thus, while cells producing CysC can secrete the protein, explaining that soluble CysC is detected in bodily fluids such as CSF and blood plasma (Bobek and Levine, 1992; Turk et al., 2008), subsequent internalization and distribution throughout the endosomal-lysosomal system is consistent with its role in cathepsin inhibition. Importantly, uptake of CysC occurs in cells other than the cell producing the protein (Ekstrom et al., 2008; Kolodziejczyk et al., 2010; Merz et al., 1997), suggesting that in vivo CysC can mediate important roles between cells through its uptake in target cell populations. CysC is also secreted in association with exosomes (Ghidoni et al., 2011), small lipid-membrane delineated extracellular vesicles (EVs) generated within late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (Lakkaraju and Rodriguez-Boulan, 2008; Simpson et al., 2008). Exosomes are stable vesicles, protecting their content from degradation, have the potential of transporting their content long distances within the extracellular space, and can be internalized by cells other than the cell responsible for their generation [reviewed in (Lakkaraju and Rodriguez-Boulan, 2008; Simpson et al., 2008)]. Thus, CysC containing exosomes are an additional pathway for the cell-to-cell propagation of CysC-mediated endosomal-lysosomal pathway regulation and cellular protection. In summary, there are data placing both cathepsins (discussed below) and CysC in extracellular as well as intracellular vesicular locations, and clarifying the subcellular distribution and site-specific functions of these proteases and their endogenous inhibitors remains fundamental to the understanding of the regulation of endosomal-lysosomal proteolysis and its disruption in neurodegenerative diseases.

1. Cathepsins and CysC can interact in multiple cellular compartments

The dynamically interacting vesicular compartments of the lysosomal system are major sites for intracellular protein turnover and the limited proteolytic processing of certain proteins (De Duve, 1966; De Duve and Wattiaux, 1966). Major routes to the lysosome include the endocytic and autophagic pathways [reviewed in (Nixon, 2013)]. The endocytic pathway (Bishop, 2003; Katzmann et al., 2002; Nixon, 2004; Seto et al., 2002; Sorkin and Von Zastrow, 2002) involves internalization of extracellular material and plasma membrane within clathrin-coated vesicles to form early endosomes (Brodsky, 1992). Early endosomes can directly mature to late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (Griffiths and Gruenberg, 1991; Murphy, 1991) that can fuse with either lysosomes (Luzio et al., 2001) or with autophagosomes generated during autophagy (Levine and Klionsky, 2004; Ogier-Denis and Codogno, 2003). While cathepsins are predominantly localized within lysosomes, they are also found in many other intracellular vesicular compartments under normal conditions (Runquist and Havel, 1991), including trans-Golgi vesicles (Lammers and Jamieson, 1988), transport vesicles (Krieger and Hook, 1992), secretory vesicles (Matsuba et al., 1989), clathrin-coated vesicles (Marks et al., 1994), and endosomes (Williams and Smith, 1993). In degenerating neurons, it has been suggested that cathepsins can be released directly into the cytoplasm after the disruption of lysosomes, with detrimental consequences for the cell (Bidere et al., 2003; Boland and Campbell, 2004; Kagedal et al., 2001; Roberg and Ollinger, 1998). In addition to their intracellular localization, cathepsins may be released outside of a cell through leakage from the endosomal-lysosomal system [reviewed in (Aits and Jaattela, 2013; Pislar and Kos, 2014)] and lysosomal exocytosis [reviewed in (Andrews, 2000; Blott and Griffiths, 2002; Jung et al., 2014; Sundler, 1997)]. In the brain, activated microglia secrete several proteases including Cat B (Buck et al., 1992). That cathepsins are readily detected in senile plaques in the brain of AD patients has led to the suggestion that degenerating neurons or their processes release lysosomal hydrolases into the extracellular space that then accumulate within amyloid deposits (Cataldo and Nixon, 1990; Cataldo et al., 1990). Given that the release of Cat B into the extracellular space can trigger neuronal apoptosis (Kingham and Pocock, 2001), can cause proteolytic tissue damage leading to organ failure, and can result in extracellular matrix destruction associated with inflammation, tumor invasion, and metastasis [reviewed in (Jochum et al., 1994; Nomura and Katunuma, 2005)], attenuating deleterious extracellular cathepsin activity in part through inhibition by extracellular CysC is likely to be important in many tissues and disease states. Internalized CysC has been shown to co-localize with the lysosomal proteins Cat D and legumain in cultured prostate cancer cells. The activity of both cysteine-protease cathepsins and legumain, enzymes potentially associated with cancer cell invasion and metastasis, was down-regulated in cell homogenates following CysC uptake, suggesting that intracellular cysteine proteases involved in cancer-promoting processes might be controlled by CysC uptake (Wallin et al., 2013). Thus, CysC is found in many of the compartments inside and outside of the cell that contain cathepsins, consistent with the idea that CysC plays a role in the regulation of cathepsin activity both within the endosomal-lysosomal pathway and more broadly when cathepsins are found outside of these compartments.

Further evidence for the functional relevance of CysC to the endosomal-lysosomal system is highlighted by the role CysC expression plays in the immune system’s response to pathogens (van Kasteren et al., 2011). A necessary component of antigen presentation is the partial cleavage of pathogen proteins within the endosomal-lysosomal pathway, primarily though the actions of cysteine-proteases (Hsing and Rudensky, 2005). Antigenic peptide fragments bind within the endosomal-lysosomal system to MHC class II molecules, with this complex then mediating antigen presentation (Bird et al., 2009). CysC is highly expressed by antigen presenting cells (Halfon et al., 1998), where it may serve the role of limiting cysteine-protease activity, resulting in the incomplete degradation of peptide antigens allowing for the efficient immunological presentation of these partial peptide fragments (Bird et al., 2009).

2. CysC in disease

CysC plays a variety of biological roles, ranging from regulating normal tissue processes such as cell proliferation and growth (Sun, 1989; Tavera et al., 1992), astrocyte differentiation (Kumada et al., 2004) and bone resorption (Lerner and Grubb, 1992) to modulating potentially pathogenic events, including infection (Bobek and Levine, 1992; van Kasteren et al., 2011), inflammatory responses (Bobek and Levine, 1992; Warfel et al., 1987), tumor metastasis (Huh et al., 1999; Taupin et al., 2000), and neurodegenerative disorders [reviewed in (Gauthier et al., 2011; Tizon and Levy, 2006)]. The relationship CysC expression appears to have to normal as well as pathological processes supports the idea that the levels of CysC in specific tissues and body fluids may serve as a marker for a variety of diseases, for disease progression, and for the effect of therapy. Indeed, CysC levels may be broadly informative of diverse stressors driving a range of cellular responses, particularly those that respond to processing and substrate clearance challenges faced by cells during aging and disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of aging-dependent diseases of the central nervous system associated with changes in cystatin C expression or function (see text for details).

| disease/disorder | proposed mechanism/observation | references |

|---|---|---|

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) |

CSF CysC levels reduced | (Pasinetti et al., 2006; Tsuji-Akimoto et al., 2009; Wilson et al.) |

| CysC accumulation in intraneuronal Bunina bodies |

(Okamoto et al., 2008) | |

| Epilepsy | Higher intraneuronal CysC levels in animal models of epilepsy (protective) |

(Aronica et al., 2001; Hendriksen et al., 2001; Lukasiuk et al., 2002) |

| Ischemia | CysC expression modify ischemia sequelae in animal models |

(Olsson et al., 2004) |

| Higher intraneuronal CysC levels in animal models of ischemia (protective) |

(Ishimaru et al., 1996; Palm et al., 1995) | |

| Lewy Body disease | CSF CysC levels reduced | (Maetzler et al., 2010) |

| CysC cerebral amyloid angiopathy (hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis, Icelandic type) |

Leu68Gln mutation in CysC is causative | (Abrahamson et al., 1990; Cohen et al., 1983; Ghiso et al., 1986; Graffagnino et al., 1995; Levy et al., 1989; Palsdottir et al., 1988) |

| Aβ cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

Co-deposited CysC may contribute to the risk of hemorrhage |

(Haan et al., 1994; Itoh et al., 1993; Maruyama et al., 1990; Vinters et al., 1990) |

| Cognitive dysfunction | Serum CysC levels altered | (Bjornstad et al., 2015; Joshi and Viljoen, 2015; Taal, 2015; Yaffe et al., 2008) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Reduced CysC secretion caused by a CysC gene polymorphism associated with increased AD risk |

(Benussi et al., 2003; Maetzler et al., 2010; Noto et al., 2005; Paraoan et al., 2004; Yamamoto-Watanabe et al.) |

| Serum CysC levels reduced | (Ghidoni et al.; Sundelof et al., 2008) | |

| CSF CysC levels reduced | (Craig-Schapiro et al.; Ghidoni et al.; Hansson et al., 2009; Mares et al., 2009; Ndjole et al.; Perrin et al.; Simonsen et al., 2007; Sundelof et al.; Zellner et al., 2009) |

|

| Higher intraneuronal CysC levels (protective) |

(Deng et al., 2001; Levy et al., 2001) | |

| Inhibition of Aβ oligomerization and fibrillation (protective) |

(Kaeser et al., 2007; Mi et al., 2007; Sastre et al., 2004; Selenica et al., 2007; Tizon et al., 2010) |

|

| Autophagy induction (protective) | (Tizon et al., 2010) |

2.1. Serum CysC in disease

Secreted CysC is detected in serum, and multiple studies have demonstrated changes in CysC concentrations in serum associated with a range of conditions, such as chronic kidney disease, urinary infection, cancer, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, glucocorticoid treatment, thyroid function, as well as related to normal aging [reviewed in (Filler et al., 2005)]. Measurement of serum CysC, in addition to creatinine, is widely used to estimate glomerular filtration rates in older individuals, with an increase in serum CysC indicative of poor kidney function (Inker et al., 2012). The importance of readily accessible and informative markers for kidney disease is underscored by the overlay of an age-dependent increase in chronic kidney disease and the fact that studies have shown that in older people chronic kidney disease is associated with an increased risk of multiple adverse outcomes including end-stage kidney disease, cardiovascular events, acute kidney injury, severe infections, cognitive decline, and death, [recently reviewed in (Bjornstad et al., 2015; Joshi and Viljoen, 2015; Taal, 2015)]. That serum CysC levels can serve as more than a simple filterable protein marker of kidney function has been suggested by studies correlating cognitive function with CysC levels in the blood. In a study of aged individuals, lower serum CysC was associated with higher risk of AD independently of age, apolipoprotein E ε4 (ApoE4) genotype, glomerular filtration rate, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, cholesterol, body mass index, smoking, education level, and serum Aβ levels (Sundelof et al., 2008). From this study it was suggested that low levels of serum CysC precede clinical AD in elderly men free of dementia at baseline, and thus may be a marker of future risk of AD, adding to the evidence for a role for CysC in the development of clinical AD (Sundelof et al., 2008). In contrast to this finding, a study of 3,030 elders showed that individuals with high levels of serum CysC had lower scores on cognitive tests compared with those with intermediate/low levels, and that those with high serum CysC levels were more likely to experience a decline in cognitive function (Yaffe et al., 2008). In this cohort, however, the brain magnetic resonance imaging and other clinical evaluation needed to determine whether the cognitive impairments were due to vascular disease, AD, or chronic kidney disease were not done (Yaffe et al., 2008), and multiple factors can drive cognitive decline associated with changes in serum CysC levels (Bjornstad et al., 2015; Joshi and Viljoen, 2015; Taal, 2015). Thus, CysC levels in the serum are affected by multiple conditions that may affect cognition, and abnormal CysC levels in the blood, either high or low, appear to be a peripheral biomarker for cognitive dysfunction and/or the development of AD. Additional studies including the necessary overlays of kidney function and other peripheral pathology known to affect serum CysC levels will be required to determine how predictive and sensitive tracking serum CysC levels is during AD.

2.2. CysC in the CSF and brain in disease

CysC has been suggested to play a role in nervous system repair following injury and disease [reviewed in (Gauthier et al., 2011; Tizon and Levy, 2006)], and CysC CSF levels in the normal brain are five times higher than they are in serum, consistent with an important physiological role for CysC in the brain (Grubb, 1992). Multiple investigators have documented alterations in CysC levels in the CSF in neurodegenerative diseases (Maetzler et al., 2010; Mares et al., 2009; Mori et al., 2009; Pasinetti et al., 2006; Tsuji-Akimoto et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009). For example, CSF CysC has shown diagnostic potential in ALS, a fatal neuromuscular disease characterized by progressive motor neuron degeneration (Wilson et al.), where CysC levels in the CSF of ALS patients have been shown to be significantly reduced compared to healthy controls (Pasinetti et al., 2006; Tsuji-Akimoto et al., 2009; Wilson et al.). In addition, longitudinal changes in CSF CysC levels correlated with the rate of ALS disease progression, and initial CSF CysC levels were predictive of patient survival, suggesting that CysC may function as a marker of disease progression and survival in ALS (Wilson et al.). That CSF CysC levels are altered during ALS disease progression is consistent with the localization of CysC to Bunina bodies, small intraneuronal inclusions contained in degenerating motor neurons that are a specific neuropathologic feature of ALS (Okamoto et al., 2008). Changes in brain CysC levels have also been observed in diverse animal models of neurodegenerative conditions including those caused by facial nerve axotomy (Miyake et al., 1996), noxious input to the sensory spinal cord (Yang et al., 2001), perforant path transections (Ying et al., 2002), hypophysectomy (Katakai et al., 1997), transient forebrain ischemia (Ishimaru et al., 1996; Palm et al., 1995), photothrombotic stroke (Pirttila and Pitkanen, 2006), and induction of epilepsy (Aronica et al., 2001; Hendriksen et al., 2001; Lukasiuk et al., 2002). While these findings argue that CysC levels in the CSF and the brain are broadly responsive to brain injury, CysC appears to also be a sensitive marker of ongoing neuronal injury and one that shows progressive disruption during disease pathology (Gauthier et al., 2011; Wilson et al.).

2.3. Low concentration of CysC in CSF and serum of AD patients

Low levels of serum CysC have been shown in AD patients (Sundelof et al., 2008). Moreover, analysis of CysC levels in serum revealed a significant tendency of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in subjects with CysC levels below the median (Ghidoni et al.), consistent with the finding by Sundelof et al. (Sundelof et al., 2008) showing that cognitively normal aged males with low CysC levels were more likely to progress to AD.

CysC levels in the CSF of AD patients have been shown to be lower when compared to non-demented individuals (Hansson et al., 2009; Simonsen et al., 2007). Like ALS, changes in CSF CysC levels in AD correlate with changes in neuronal CysC as detected by tissue immunolabeling, with specific neuronal cell populations in the brains of patients with AD showing increased intracellular CysC levels (Deng et al., 2001; Levy et al., 2001). Interestingly, CSF CysC levels showed a positive correlation with changes in both tau and Aβ42 levels in the CSF, independent of age, gender, and ApoE genotype (Sundelof et al.), and a number of investigators have suggested that changes in CSF CysC levels might serve as a biomarker for AD (Craig-Schapiro et al.; Ghidoni et al.; Mares et al., 2009; Ndjole et al.; Perrin et al.; Simonsen et al., 2007; Sundelof et al.; Zellner et al., 2009). Demented Lewy body disease patients also showed decreased CSF CysC levels (Maetzler et al., 2010). Given that a large proportion of demented Lewy body disease patients have AD-like pathology including Aβ plaques (Catafau and Bullich, 2015; Gomperts, 2014), a finding of reduced CSF CysC levels may be consistent across multiple diseases showing Aβ amyloid pathology.

3. CysC in Alzheimer’s disease

AD pathology is characterized by the formation of extracellular amyloid deposits in the brain composed mainly of Aβ, a processing product of the amyloid β precursor protein (APP); intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed mainly of hyperphosphorylated tau; loss of neurons with atrophy of specific brain areas; and decreased synapse number in surviving neurons. In this section, we discuss the involvement of CysC in AD as suggested by immunohistochemical, genetic, and biochemical studies.

3.1. CysC co-deposition with Aβ

A potential role for cystatins in AD pathobiology was originally suggested by the discovery of their co-localization with Aβ. CysC was the first cystatin found co-localized with accumulated Aβ, and early reports demonstrated the presence of CysC in both amyloid-laden vascular walls and within parenchymal Aβ senile plaques (Haan et al., 1994; Itoh et al., 1993; Levy et al., 2001; Maruyama et al., 1990; Vinters et al., 1990). Cystatin A (CysA) and cystatin B (CysB), also called stefin B, have also been demonstrated in senile plaques in the brain of AD patients (Bernstein et al., 1994; Ii et al., 1993), suggesting that disruption of the endosomal-autophagic-lysosomal system in AD [reviewed in (Nixon, 2013)] is reflected in the broad association of cathepsins and their inhibitors with amyloid plaque pathology.

CysC also co-localizes with Aβ deposits in the parenchyma and vasculature in brains of transgenic mice overexpressing human APP (Levy et al., 2001; Steinhoff et al., 2001). Increased vascular amyloid with aging in the APP23 transgenic mouse line was found to correspond with increased CysC immunolabeling of the cerebrovascular amyloid (Winkler et al., 2001). Similar to CysC staining of Aβ deposits in human brains, plaque-associated CysC immunoreactivity was restricted to a subpopulation of amyloid-laden vessels and was clearly less intense than Aβ immunolabeling (Levy et al., 2001; Steinhoff et al., 2001; Winkler et al., 2001). Neuropathologies characteristic of AD and normal aging in humans can also be seen in senescent non-human primates (Price et al., 1994; Walker et al., 1990; Wisniewski and Terry, 1973). For example, in aged rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) amyloid deposition can occur in senile plaques with relatively minor vascular involvement whereas cerebrovascular deposits in aged squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) are usually more conspicuous than senile plaques (Walker et al., 1990). Co-localization of Aβ and CysC has been demonstrated in both parenchymal and vascular deposits in the brains of aged rhesus monkeys and in vascular amyloid in brains of aged squirrel monkeys (Wei et al., 1996).

3.2. The contribution of CysC to vascular hemorrhage in AD

While Aβ usually accumulates both in cerebral blood vessels and in brain parenchyma as amyloid plaques, in some cases Aβ deposits predominantly in the cerebral vasculature (Vinters, 2001). Broadly, the deposition of fibrillar protein aggregates in the walls of arteries, arterioles, and sometimes capillaries and veins of the central nervous system is known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a pathology that is often associated with subsequent hemorrhage (Nagai et al., 2008). A role for CysC in CAA-related hemorrhage was suggested by immunohistochemical studies that revealed co-localization of CysC and Aβ in amyloid-laden vascular walls (Haan et al., 1994; Itoh et al., 1993; Maruyama et al., 1990; Vinters et al., 1990). It was reported that only patients showing co-localization of CysC and Aβ immunoreactivity in their diseased cerebral vessels suffered fatal subcortical hemorrhages (Maruyama et al., 1990). The amount of CysC in the amyloid deposits is much lower than the amount of Aβ (Nagai et al., 1998) and while Aβ is fibrillar, CysC appears to be soluble (Maruyama et al., 1992). It has been suggested that CysC deposition occurs secondarily to Aβ deposition and that the accumulation of CysC may increase the predisposition to cerebral hemorrhages (Itoh et al., 1993). CysC co-localization with vascular amyloid composed of a peptide other than Aβ was also observed in familial cerebral amyloid angiopathy, British type, (Ghiso et al., 1995), arguing that CysC may play a role in CAA and hemorrhage in a variety of diseases that involve deposition of heterogeneous types of amyloid proteins.

3.3. Intracellular CysC in AD brain

Immunohistochemical analyses have consistently shown intense CysC immunoreactivity in neurons and activated glia in the cerebral cortex in AD patients as well as in some aged humans (Deng et al., 2001; Yasuhara et al., 1993). Strong neuronal staining of CysC in AD brains was seen primarily in pyramidal neurons in cortical layers III and V (Deng et al., 2001; Levy et al., 2001). The regional distribution of this CysC neuronal immunostaining followed the pattern of neuronal susceptibility in AD brains: the strongest staining was found in the entorhinal cortex, in the hippocampus, and in the temporal cortex; fewer pyramidal neurons were stained in the frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes (Deng et al., 2001). Using an end-specific antibody to the carboxyl-terminus of Aβ42, intracellular Aβ immunoreactivity was observed in the same neuronal subpopulations as CysC, demonstrating that CysC is abundant within the same pyramidal neurons in which Aβ42 accumulates (Levy et al., 2001).

3.4. Linkage of CysC gene polymorphism with AD

Several studies have linked polymorphisms within the human CysC encoding gene [CST3; localized on chromosome 20 (Abrahamson et al., 1989; Saitoh et al., 1989)] to an increased risk of developing AD (Bertram et al., 2007; Beyer et al., 2001; Cathcart et al., 2005; Crawford et al., 2000; Finckh et al., 2000; Goddard et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2002). In addition to being a risk factor for disease development, CysC polymorphisms were found to be associated with higher rates of decline and disease progression in AD patients (Schmidt et al., 2012). Other studies, however, have failed to show this association between CST3 and AD, including within a German cohort (Dodel et al., 2002), a Dutch sample with early-onset AD (Roks et al., 2001), Japanese AD patients (Maruyama et al., 2001), a Finnish population (Helisalmi et al., 2009), and within additional early-onset AD families (Parfitt et al., 1993). Further studies have found a connection between this CST3 polymorphism and AD in Caucasian populations, but not within Asian populations (Hua et al.; Wang et al., 2008). The general consensus from these studies is that the CST3 gene shows some linkage to AD-risk, although the risk may vary across populations and is not apparent in early-onset AD cohorts. For updated information on the linkage of the CST3 polymorphism with AD, see the Alzgene Internet site of the Alzheimer Research Forum. In addition to AD, polymorphisms in the CysC gene have been associated with the likelihood of developing two additional neurodegenerative disorders: frontotemporal lobar degeneration (Benussi et al., 2010) and cerebral white matter lesions (Mitaki et al., 2011).

That allelic variation in the CST3 gene may contribute to risk of AD and other neurodegenerative disorders is further supported by experimental evidence suggesting functional differences between the encoded proteins. The human CST3 gene (Abrahamson et al., 1989; Saitoh et al., 1989) has three genetically linked base substitutions in the 3’ region (Balbin and Abrahamson, 1991; Balbin et al., 1993). A G73A transition in exon 1 results in Ala/Thr variation in the coding region of CST3, within the signal peptide. This amino acid exchange from Ala to Thr at the −2 position for signal peptide-cleavage alters the hydrophobicity profile of the signal sequence (Finckh et al., 2000), resulting in less efficient cleavage of the signal peptide and thus reduced secretion of CysC (Benussi et al., 2003). The CST3 gene G73A polymorphism in vivo affects CysC serum levels (Noto et al., 2005) as well as CysC CSF levels (Maetzler et al., 2010; Yamamoto-Watanabe et al.). Additionally, a study of the targeting of the Thr haplotype in cultured retinal pigment epithelial and HeLa cells has shown that a proportion of the Thr protein undergoes incorrect trafficking to the mitochondria, resulting in a substantial reduction in the efficiency of targeting CysC for secretion (Paraoan et al., 2004). Decreased cellular CysC secretion due to the G73A polymorphism found in the CysC gene offers a mechanism for the increased-risk of late-onset sporadic AD conferred by this polymorphism, consistent with reduced brain CysC levels showing an association with the disease.

4. CysC cerebral amyloidosis

While Aβ pathology in AD is the most common cause of CAA, accumulation of other amyloidogenic proteins can result in CAA. Relevant to a discussion of CysC, hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis, Icelandic type (HCHWA-I) (Arnason, 1935; Gudmundsson et al., 1972), also called hereditary cystatin C amyloid angiopathy (HCCAA) (Olafsson et al., 1996), is an autosomal dominant form of CAA caused by a mutation in CysC. Amyloid deposition in cerebral and spinal arteries and arterioles of HCHWA-I patients leads to recurrent hemorrhagic strokes causing serious brain damage and eventually fatal stroke (Gudmundsson et al., 1972). The amyloid deposited is composed mainly of CysC containing a Leu68Gln mutation (Abrahamson et al., 1990; Cohen et al., 1983; Ghiso et al., 1986; Levy et al., 1989; Palsdottir et al., 1988). A point mutation identical to that found in the CST3 gene of these Icelandic patients and thus resulting in the Leu68Gln amino acid substitution was also identified in one copy of the CTS3 gene in a Croatian man who developed CAA with intracerebral hemorrhage (Graffagnino et al., 1995). Thus, sporadic CAA in some patients may be associated with mutations in the CST3 gene (Graffagnino et al., 1995; McCarron et al., 2000). Differences in the amino acid at this same residue (amino acid 68 of CysC) is seen in non-human primates: rhesus monkeys express CysC containing the wild-type human Leu68 whereas the CysC of squirrel monkeys contains a Met at position 68 (Wei et al., 1996). Aged rhesus monkeys predominantly develop parenchymal Aβ amyloidosis, while squirrel monkey have a high incidence of Aβ-containing CAA (Walker et al., 1990; Wei et al., 1996), suggesting that, as in humans expressing CysCLeu68Gln, amino acid difference in CysC at residue 68 may contribute to the likelihood of vascular amyloid accumulation. Highlighting the biological complexity of the multiple activities of CysC, an additional difference between squirrel and rhesus monkeys was found at position 10, a residue in CysC that was shown to affect the specificity of the inhibitor for different cysteine proteases (Lindahl et al., 1994). Thus, a single amino-acid substitution in CysC can lead to CysC-CAA in humans, while changes at this same residue in primates are linked to differences in the localization Aβ amyloid, which is known to contain co-deposited CysC (Wei et al., 1996).

5. Neuroprotection by CysC

As discussed above, strong CysC immunoreactivity has been reported in specific neuronal populations in the cerebral cortex in some humans as they age, and this is a generalized finding in AD patients (Deng et al., 2001; Levy et al., 2001; Yasuhara et al., 1993). Enhanced CysC expression in specific cell populations is also observed in other neurodegenerative conditions, such as epilepsy, ischemia, and progressive myoclonus epilepsy (Aronica et al., 2001; Hendriksen et al., 2001; Ishimaru et al., 1996; Kaur et al., 2010; Lukasiuk et al., 2002; Palm et al., 1995). Discussions of the role that enhanced CysC expression plays in these disorders has lead to contradictory interpretations, with arguments being made that increased CysC cellular expression in the brain is associated with neurodegenerative and pathological processes, or alternatively, is part of a neuroprotective response aimed at preventing or minimizing neurodegeneration. In this section, we provide a description of neuroprotective mechanisms activated by CysC in support of the hypothesis that reduced levels of CysC available to neurons can hamper the ability of the brain to prevent neurodegeneration in various pathological conditions.

5.1 Protection by inhibition of cysteine proteases

An imbalance in the expression of cathepsins and their inhibitors may cause or exacerbate existing neuropathological changes, and increased CysC expression may represent an attempt to curb excessive cathepsin activity. An imbalance between cysteine proteinases and endogenous inhibitors has been associated with different diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (Trabandt et al., 1991), renal failure (Kabanda et al., 1995), multiple sclerosis (Bever and Garver, 1995; Nagai et al., 2003), muscular dystrophy (Sohar et al., 1988), inflammatory periodontal disease (Lah et al., 1993), inflammatory lung disease (Buttle et al., 1991), inflammation and trauma (Assfalg-Machleidt et al., 1990), and various types of cancer (Calkins and Sloane, 1995; Duffy, 1996; Kos et al., 2000; Thomssen et al., 1995). Increased expression in the brain of several cathepsins has been documented in response to injuries, such as in transient ischemia (Nitatori et al., 1995; Yamashima et al., 1998). Pharmacologic inhibitors of Cat B and Cat L have been found to reduce neuronal damage in the hippocampus after ischemia (Tsuchiya et al., 1999; Yamashima et al., 1998), suggesting that balancing an injury-driven increase in cathepsin expression with the appropriate changes in the expression of an endogenous inhibitor, such as CysC, may be important in modulating a potentially damaging brain response to injury.

Consistent with the idea that CysC levels regulate cathepsin activity, in vivo studies demonstrated increased Cat B activity in the brain of CysC knockout mice, confirming the inhibitory function of CysC within the brain (Sun et al., 2008). In support of the idea that CysC expression may moderate brain damage following injury, larger brain infarcts were found in CysC knockout mice when compared to wild-type mice after focal ischemia induced by 40 minutes of occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (Olsson et al., 2004). However, brain damage in the CA3 region of the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, and cortex was diminished in CysC knockout mice after global ischemia induced by 12 minutes of occlusion of both common carotid arteries (Olsson et al., 2004). The different responses after focal and global ischemia in CysC knockout mice suggest that the protective role imparted by CysC is differential and restricted to certain brain regions or certain brain insults.

5.2. CysC overexpression can rescue neurodegeneration caused by loss of CysB

Further evidence that CysC expression in vivo can reduce neurodegeneration by inhibition of cysteine protease has come from studies of a mouse model of an inherited neurodegenerative disorder, progressive myoclonic epilepsy (Kaur et al., 2010). In the rare autosomal disorder Unverricht-Lundborg disease (EPM1) (Houseweart et al., 2003; Lalioti et al., 1997; Pennacchio et al., 1996), the most common form of progressive myoclonus epilepsies (Lafreniere et al., 1997), loss-of-function mutations in the CysB gene lead to the disorder (Houseweart et al., 2003; Lalioti et al., 1997; Pennacchio et al., 1996). CysB is also an inhibitor of cysteine proteases, including Cat B, Cat H, Cat L, and Cat S (Barrett, 1986). While CysB has overlapping inhibitory activity with CysC, it is a member of the cystatin family 1 of cysteine protease inhibitors and evolutionarily distinct (Barrett et al., 1986). CysB is mainly localized in lysosomes (Kaur et al., 2010) and also diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (Houseweart et al., 2003; Kaur et al., 2010). EPM1 has an onset of symptoms at 6–15 years of age and the disease progresses with myoclonic and tonic-clonic seizures (Koskiniemi et al., 1974; Norio and Koskiniemi, 1979), neurological decline, and severe ataxia (Eldridge et al., 1983; Koskiniemi et al., 1974). A CysB knockout (CysBKO) mouse model of EPM1 develops myoclonic seizures and ataxia, similar to the symptoms seen in the human disease (Pennacchio et al., 1998). Degeneration of cerebellar granule cells (Pennacchio et al., 1998), hippocampal neurons, and cells within the entorhinal cortex are seen in the brains of CysBKO mice (Shannon et al., 2002). These mice also show gliosis and increased expression of apoptotic and glial activation genes (Lehesjoki, 2003; Shannon et al., 2002). The progressive cerebellar atrophy caused by CysB deficiency implicates a required role for CysB expression in the development of the cerebellum and in normal neuronal survival. Increased mRNA, protein, and enzymatic activity levels of the two lysosomal enzymes Cat B and Cat D were also demonstrated in the brains of CysBKO mice (Kaur et al., 2010), and multiple findings suggest that increased proteolysis by lysosomal cathepsins is responsible for the phenotypic characteristics of EPM1 (Houseweart et al., 2003; Lieuallen et al., 2001; Rinne et al., 2002). Consistent with excess cathepsin activity driving the disease, deletion of Cat B in CysBKO mice resulted in a reduction in the amount of cerebellar granule cell apoptosis (Houseweart et al., 2003).

CysC mRNA and protein were found to be upregulated in the brains of CysBKO mice (Kaur et al., 2010), suggestive of an intrinsic adaptive and neuroprotective response to limit damage to neurons caused by the over activity of cathepsins in the absence of CysB. However, the increase in endogenous CysC expression in these mice is clearly not sufficient to fully counteract the progression of the disease (Kaur et al., 2010). In order to test the hypothesis that CysC overexpression can rescue the loss-of-function of CysB in EPM1, CysBKO mice were crossbred with CysC overexpressing transgenic mice (Levy et al., 1989; Pawlik et al., 2002). CysC overexpression in CysBKO mice decreased Cat B and Cat D activities in the brain (Kaur et al., 2010), and rescued clinical symptoms and neuropathologies, including deficient motor coordination, cerebellar atrophy, neuronal loss in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex, and the gliosis caused by CysB deficiency (Kaur et al., 2010). These data show that CysC partially prevents neurodegeneration in CysBKO mice through inhibition of cathepsins activity, and highlight the importance in the brain of the balance between cathepsins and their endogenous inhibitors.

5.3. Protection by inhibition of Aβ oligomerization and amyloid fibril formation

The co-localization of CysC with Aβ in parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposits in AD (Haan et al., 1994; Itoh et al., 1993; Levy et al., 2001; Maruyama et al., 1990; Vinters et al., 1990) suggests that CysC may directly associate with the Aβ peptide, an idea that has been supported by extensive experimental findings. Co-immunoprecipitation of cell lysate or medium proteins revealed that CysC binds to full-length APP and to secreted soluble APP, respecively, and deletion mutants of APP localized the CysC binding site to the Aβ region within APP (Sastre et al., 2004). The association of CysC with APP was confirmed using a method for the in vivo mapping of protein interactions in intact mouse tissue (Bai et al., 2008). Furthermore, CysC not only binds to Aβ sequences within APP, but also to the peptide itself, with a specific, saturable and high affinity binding between CysC and both Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 (Sastre et al., 2004). Interestingly, CysC association with Aβ resulted in a concentration dependent inhibition of Aβ amyloid fibril formation in vitro (Sastre et al., 2004), and subsequent in vitro studies also demonstrated that CysC association with Aβ inhibits Aβ oligomerization (Selenica et al., 2007; Tizon et al., 2010a). A structural model of the human CysC-Aβ complex using a combination of selective proteolytic excision and high-resolution mass spectrometry identified a specific C-terminal epitope, HCC (101–117), as the Aβ-binding region within CysC (Juszczyk et al., 2009).

This direct interaction between CysC and Aβ is likely to explain the colocalization of CysC with amyloid-β pathology. More intriguing, however, is the possibility suggested from the in vitro aggregation studies that CysC can inhibit Aβ oligomerization and fibrillation. Such an anti-amyloidogenic role for CysC was shown in vivo by crossing Aβ depositing APP transgenic mice with mice overexpressing human CysC. Several lines of transgenic mice, expressing human CysC under control sequences of the human CysC gene (Mi et al., 2007) or specifically in cerebral neurons (Kaeser et al., 2007), were crossbred with mice overexpressing human APP. CysC bound to the soluble, non-pathological form of Aβ in the brains and plasma of these mice and inhibited the aggregation and deposition of Aβ plaques in the brain (Kaeser et al., 2007; Mi et al., 2007). CysC and Aβ have also been shown to co-precipitate from the brain and CSF of AD patients and control individuals (Mi et al., 2009). The association of CysC with Aβ in brain from control individuals as well as in CSF revealed an interaction of these two polypeptides in their soluble form (Mi et al., 2009), showing that CysC can interact in humans with Aβ prior to Aβ deposition and is therefore poised to reduce Aβ aggregation in the human brain as has been shown in vitro (Sastre et al., 2004; Selenica et al., 2007; Tizon et al., 2010a) and using in vivo models (Kaeser et al., 2007; Mi et al., 2007). Additionally, that the association between Aβ and CysC prevents Aβ accumulation and fibrillogenesis in experimental systems argues that CysC plays a protective role in the pathogenesis of AD, and may explain in part why a decrease in CysC concentration caused by the CST3 polymorphism (as discussed above) or by specific presenilin 2 mutations (discussed below) can lead to the development of the disease.

In addition to CysC, Aβ interacts with other amyloidogenic/amyloid-associated proteins including transthyretin (Buxbaum et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2007; Schwarzman et al., 1994; Schwarzman et al., 2004), gelsolin (Chauhan et al., 1999), α2-macroglobulin (Kuo et al., 2000), and crystallin-αB (Wilhelmus et al., 2006). Such interactions appear to inhibit Aβ fibril formation (Kaeser et al., 2007; Matsuoka et al., 2003; Mi et al., 2007; Sastre et al., 2004; Skerget et al., 2010; Wilhelmus et al., 2006). Wilhelmus et al. (Wilhelmus et al., 2007) suggested that proteins that co-localize with the pathological lesions of AD, such as apolipoproteins and heparan sulfate proteoglycans, bind amyloidogenic proteins and may be involved in conformational changes of Aβ and in the clearance of Aβ from the brain via phagocytosis or active transport across the blood-brain barrier. Thus, CysC appears to belong to a larger group of unrelated proteins that, through their ability to interact with Aβ, can inhibit amyloid formation and therefore have a neuroprotective function in diseases such as AD.

In addition to these anti-amyloidogenic properties, CysC directly protects neuronal cells from Aβ toxicity. The extracellular addition of human CysC together with either preformed oligomeric or fibrillar Aβ to cultured primary hippocampal neurons and to a neuronal cell line increased cell survival (Tizon et al., 2010a). These experimental findings show that modifications in CysC expression levels in the central nervous system, and possibly also in the periphery, can not only affect amyloid-β deposition, but may also serve to modulate the cellular toxicity of aggregated Aβ.

5.4. Protection by induction of autophagy

The autophagic pathway consists of the sequestration and subsequent lysosomal turnover of organelles and cytoplasmic content. During macroautophagy a region of cytoplasm and organelles are sequestered by a membrane that is created mainly from endoplasmic reticulum under the direction of multiple proteins, including the microtubule-associated protein LC3-II, leading to the formation of a double-membrane-limited autophagic vacuole or autophagosome (Asanuma et al., 2003; Klionsky and Emr, 2000; Mizushima et al., 2002). Autophagosomes become autolysosomes by fusing with late endosomes or lysosomes (Dunn, 1990). Autophagy occurs in normal cells to maintain cellular constituent turnover, and is greatly increased in cells under pathological conditions, such as trophic stress or nutritional deprivation, hypoxia, ischemia, endotoxin shock, and metabolic inhibition (Glaumann et al., 1981). Autophagy induction may protect cells from apoptosis by eliminating damaged mitochondria and other organelles that have the potential to trigger apoptosis (Brunk et al., 1995; Larsen and Sulzer, 2002; Tolkovsky et al., 2002). However, sustained over-activity or dysfunction of the autophagic pathway in pathologic states mediates a caspase-independent form of cell death that shares certain features with apoptosis (Baehrecke, 2003; Borsello et al., 2003; Bursch, 2001; Guimaraes et al., 2003; Hornung et al., 1989).

An in vitro study of the effect of CysC on cells of neuronal origin exposed to various cytotoxic challenges has shown that CysC protects neuronal cells from death by a mechanism that does not require cathepsin inhibition (Tizon et al., 2010b). Moreover, primary cortical neurons isolated from the brains of CysC overexpressing transgenic mice were protected from spontaneous death induced by culturing and from B27-supplement-deprivation, and cells isolated from CysC knockout mice were more sensitive to in vitro toxicity compared to cells isolated from brains of wild-type mice (Tizon et al., 2010b). Using multiple approaches, it was demonstrated that CysC induces autophagy in cells under basal conditions, and enhances autophagic activation in cells exposed to nutritional deprivation and oxidative stress (Tizon et al., 2010b). Notably, CysC induces fully functional autophagy via the mTOR pathway that includes competent proteolytic clearance of autophagy substrates by lysosomes (Tizon et al., 2010b). Thus, it appears that CysC levels can serve to modulate the efficiency of the autophagic pathway, an activity that would be beneficial given that enhanced autophagic lysosomal turnover can protect against neurodegeneration [reviewed in (Nixon, 2013)]. Another in vitro study has shown that exogenously added CysC protected neuronal cells, including N2a cells and primary cultured motor neurons, against ALS-linked mutant Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD1)-mediated toxicity (Watanabe et al., 2014). Interestingly, the neuroprotective property of CysC was dependent on the coordinated activation of two distinct pathways: autophagy induction through AMPK-mTOR pathway and inhibition of Cat B. Furthermore, exogenously added CysC was incorporated into the cells via clathrin-dependent endocytosis and subsequently localized to lysosomes. CysC apparently leaked from the lysosomes and aggregated in the cytosol when ALS-related SOD1 mutants were expressed, suggesting a relationship between the neuroprotective activity of CysC and Bunina body formation (Watanabe et al., 2014).

In vivo, CysC-mediated protection via autophagy has been shown in a rat experimental model of subarachnoid hemorrhage with subsequent brain injury, where CysC treatment was found to reduce brain injury following injection of blood into the brain (Liu et al., 2014). Markers of autophagy, which were increased in the cortex after the induction of the experimental hemorrhage, were further up regulated with CysC therapy. Learning deficits were reduced by CysC treatment (Liu et al., 2014), consistent with the idea that CysC can be neuroprotective, possibly through activating the autophagic pathway (Tizon et al., 2010b).

5.5. Protection by neurogenesis

CysC can also regulate cell proliferation (Sun, 1989; Tavera et al., 1992). In rats undergoing acute hippocampal injury or status epilepticus-induced epileptogenesis, the expression of CysC mRNA and protein are increased in the hippocampus and in the dentate gyrus (Aronica et al., 2001; Hendriksen et al., 2001; Lukasiuk et al., 2002), with CysC mRNA expression increasing concurrently with the period of prominent neurogenesis (Nairismagi et al., 2004; Parent et al., 1997). In CysC knockout mice, the basal level of neurogenesis in the subgranular layer of dentate gyrus was decreased (Pirttila et al., 2005; Taupin et al., 2000), and the proliferation and migration of newborn granule cells in the dentate gyrus impaired (Pirttila et al., 2005), more directly implicating CysC in regulating neurogenesis. Supporting these in vivo findings, the addition of CysC into the culture medium of primary brain cells increased the number of neurospheres formed from embryonic brain as well as nestin-positive cells (Hasegawa et al., 2007). In this study, CysC was also shown to regulate glial development, increasing the number of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive cells (Hasegawa et al., 2007). Thus, another mechanism by which CysC may be protective following injury could involve the induction of neurogenesis and/or glial differentiation and a glial response to injury.

5.6. Exosome-associated CysC

In addition to being targeted to the classical secretory pathway, CysC is secreted in association with exosomes (Ghidoni et al., 2011), a recently identified family member of bioactive secreted vesicles. Exosomes are generated in late endosomes/multivesicular bodies, where sequestered proteins, lipids, and other cellular components are targeted either for degradation in lysosomes or for release into the extracellular space in association with exosomes [reviewed in (Lakkaraju and Rodriguez-Boulan, 2008; Simpson et al., 2008)]. A pathogenic role for exosome-derived Aβ in amyloid deposition has been suggested by the findings that exosome-associated proteins are enriched in amyloid plaques in AD brains (Rajendran et al., 2006); that exosomes isolated from tissue culture media contain full length APP (flAPP), C-terminal fragments of the APP (APP-CTFs), Aβ, and key enzymes that cleave both flAPP and APP-CTFs, including α-secretase (ADAM10), β-secretase (BACE1), and all components of the γ-secretase complex; and that exosomes are one site where APP processing occurs (Escrevente et al., 2008; Rajendran et al., 2006; Sharples et al., 2008; Vingtdeux et al., 2007). Importantly, APP, APP-metabolites, and APP secretases have been identified in exosomes isolated from brain (Perez-Gonzalez et al., 2012). Exosomes are stable vesicles, protecting their content from degradation, and therefore have the potential of transporting APP, APP-CTFs, and Aβ to sites distant from the cell that produced them as well as being a source of ongoing Aβ generation in the extracellular space. Furthermore, Aβ may bind nonspecifically to the surface of the lipid-rich and stable exosomal membrane and/or to Aβ-binding receptors such as Lrp8 and PrP [reviewed in (Joshi et al., 2015)], and these associations may form a site for Aβ aggregation, oligomerization, and/or seeding for amyloid.

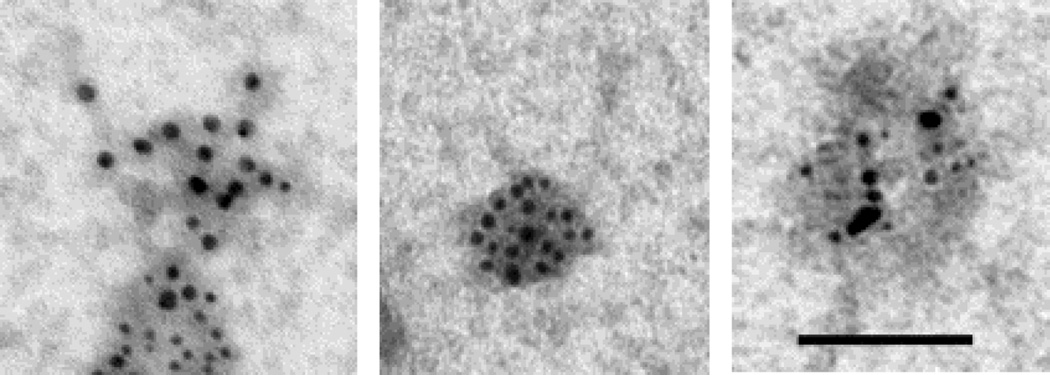

Using our published protocol (Perez-Gonzalez et al., 2012), we isolated extracellular vesicles that are enriched in exosomes from the brains of the Tg2576 Swedish-mutant APP overexpressing mouse line at 6–9 weeks of age. The enrichment of exosomes within the extracellular vesicles isolated was confirmed using immuno-EM for the exosomal marker TGS101 (data not shown). Dual immuno-gold labeling with antibodies to CysC and with 4G8 showed the presence of both CysC and flAPP and its metabolites, including APP-CTFs and Aβ, in the same exosomes isolated from the brains of the Tg2576 mice (Figure 1). The presence of both APP and its metabolites and CysC in exosomes suggests that exosomes are a site where CysC can prevent Aβ aggregation and that a reduction in CysC expression or CysC content in exosomes may predispose to AD pathogenesis. This idea is support by findings showing that two of the mutations in the presenilin 2 (PS2) gene that are linked to familial early-onset AD (FAD; PS2M239I and PS2T122R) alter CysC trafficking in mouse primary neurons and cause reduced CysC secretion (Ghidoni et al., 2007). Over-expression of PS2M239I and PS2T122R resulted in decreased levels of CysC within exosomes (Ghidoni et al., 2011). Given both a protective role for CysC and the anti-Aβ amyloidogenic properties of CysC, the reduction in CysC levels may represent one molecular factor increasing the risk of AD in FAD patients carrying these two PS2 mutations.

Figure 1. Exosomes isolated from the brains of Tg2576 mice contain both CysC and Aβ.

Electron micrographs of exosomes dually labeled with an anti-CysC antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Billerica, MA; 6 nm gold particles) and an antibody the binds to flAPP, APP-CTFs, and Aβ (4G8; Covance ImmunoTechnologies, Denver, PA; 10 nm gold particles) (bar=100 nm).

CONCLUSIONS

Immunohistochemical, genetic, and biochemical studies suggest that CysC can play a role in multiple neurodegenerative disorders. CysC co-localizes with Aβ in the brain, and biochemical studies have shown that the binding of CysC to soluble Aβ prevents Aβ oligomerization, fibril formation, and amyloid deposition. Genetic studies have shown a linkage between a CysC gene polymorphism with AD, which is likely to be explained by a decrease in secretion of CysC. While some studies have shown that CysC can be toxic to cells under certain conditions, there are now multiple reports showing that under specific conditions, increasing CysC levels can be protective. Given the multifaceted biology of CysC, which can inhibit cathepsins, regulate proteolysis in the endosomal-lysosomal system, induce autophagy, bind to and alter the biology of other peptides/proteins such as Aβ, and regulate cell proliferation and cell migration, one would anticipate that the impact of CysC expression and function on disease progression has the potential to be complex. The current experimental evidence is, indeed, consistent with CysC playing many roles in AD risk and pathobiology, with many of these mechanistic pathways involved. Overall, however, the findings within the field currently argue that a reduction in brain CysC levels is likely to increase the risk of AD and the neurodegeneration associated with the disease. Thus, therapeutically enhancing CysC within the brain should be further investigated as a way to prevent, postpone, or halt the disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AG017617 and AG037693).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Gene overview of all published AD-association studies for CST3. http://www.alzforum.org/res/com/gen/alzgene/geneoverview.asp?geneid=66. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson M, Buttle DJ, Mason RW, Hansson H, Grubb AO, Lilja H, Ohlsson K. Regulation of cystatin C activity by serine proteinases. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1991;50:587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson M, Islam MQ, Szpirer J, Szpirer C, Levan G. The human cystatin C gene (CST3), mutated in hereditary cystatin C amyloid angiopathy, is located on chromosome 20. Hum Genet. 1989;82:223–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00291159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson M, Olafsson I, Palsdottir A, Ulvsback M, Lundwall A, Jensson O, Grubb AO. Structure and expression of the human cystatin C gene. Biochem J. 1990;268:287–294. doi: 10.1042/bj2680287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aits S, Jaattela M. Lysosomal cell death at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1905–1912. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews NW. Regulated secretion of conventional lysosomes. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:316–321. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnason A. Apoplexie und ihre Vererbung. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1935;VII(Suppl):1–180. [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E, van Vliet EA, Hendriksen E, Troost D, Lopes da Silva FH, Gorter JA. Cystatin C, a cysteine protease inhibitor, is persistently up-regulated in neurons and glia in a rat model for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1485–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Tanida I, Shirato I, Ueno T, Takahara H, Nishitani T, Kominami E, Tomino Y. MAP-LC3, a promising autophagosomal marker, is processed during the differentiation and recovery of podocytes from PAN nephrosis. Faseb J. 2003;17:1165–1167. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0580fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assfalg-Machleidt I, Jochum M, Nast-Kolb D, Siebeck M, Billing A, Joka T, Rothe G, Valet G, Zauner R, Scheuber HP, et al. Cathepsin B-indicator for the release of lysosomal cysteine proteinases in severe trauma and inflammation. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1990;371(Suppl):211–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehrecke EH. Autophagic programmed cell death in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:940–945. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Markham K, Chen F, Weerasekera R, Watts J, Horne P, Wakutani Y, Bagshaw R, Mathews PM, Fraser PE, Westaway D, St George-Hyslop P, Schmitt-Ulms G. The in vivo brain interactome of the amyloid precursor protein. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:15–34. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700077-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbin M, Abrahamson M. SstII polymorphic sites in the promoter region of the human cystatin C gene. Hum Genet. 1991;87:751–752. doi: 10.1007/BF00201742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbin M, Grubb AO, Abrahamson M. An Ala/Thr variation in the coding region of the human cystatin C gene (CST3) detected as a SstII polymorphism. Hum Genet. 1993;92:206–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00219694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barka T, van der Noen H, Patil S. Cysteine proteinase inhibitor in cultured human medullary thyroid carcinoma cells. Lab Invest. 1992;66:691–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A, Rawlings N, Davies M, Machleidt W, G S, Turk V. Cysteine proteinase inhibitors of the cystatin superfamily. In: Barrett AJ, Salvesen GS, editors. Proteinase inhibitors. Amsterdam: Elsvier; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AJ. The cystatins: a diverse superfamily of cysteine peptidase inhibitors. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1986;45:1363–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benussi L, Ghidoni R, Galimberti D, Boccardi M, Fenoglio C, Scarpini E, Frisoni GB, Binetti G. The CST3 B haplotype is associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:143–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benussi L, Ghidoni R, Steinhoff T, Alberici A, Villa A, Mazzoli F, Nicosia F, Barbiero L, Broglio L, Feudatari E, Signorini S, Finckh U, Nitsch RM, Binetti G. Alzheimer disease-associated cystatin C variant undergoes impaired secretion. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;13:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, Kirschke H, Wiederanders B, Pollak KH, Zipress A, Rinne A. The possible place of cathepsins and cystatins in the puzzle of Alzheimer disease: a review. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1996;27:225–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02815106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, Rinne R, Kirschke H, Jarvinen M, Knofel B, Rinne A. Cystatin A-like immunoreactivity is widely distributed in human brain and accumulates in neuritic plaques of Alzheimer disease subjects. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33:477–481. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bever CT, Jr, Garver DW. Increased cathepsin B activity in multiple sclerosis brain. J Neurol Sci. 1995;131:71–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K, Lao JI, Gomez M, Riutort N, Latorre P, Mate JL, Ariza A. Alzheimer's disease and the cystatin C gene polymorphism: an association study. Neurosci Lett. 2001;315:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidere N, Lorenzo HK, Carmona S, Laforge M, Harper F, Dumont C, Senik A. Cathepsin D triggers Bax activation, resulting in selective apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) relocation in T lymphocytes entering the early commitment phase to apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31401–31411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird PI, Trapani JA, Villadangos JA. Endolysosomal proteases and their inhibitors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:871–882. doi: 10.1038/nri2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop NE. Dynamics of endosomal sorting. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;232:1–57. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(03)32001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornstad P, Cherney DZ, Maahs DM. Update on Estimation of Kidney Function in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:57. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0633-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blott EJ, Griffiths GM. Secretory lysosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:122–131. doi: 10.1038/nrm732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobek LA, Levine MJ. Cystatins-inhibitors of cysteine proteinases. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1992;3:307–332. doi: 10.1177/10454411920030040101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland B, Campbell V. Abeta-mediated activation of the apoptotic cascade in cultured cortical neurones: a role for cathepsin-L. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:83–91. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsello T, Croquelois K, Hornung JP, Clarke PG. N-methyl-d-aspartate-triggered neuronal death in organotypic hippocampal cultures is endocytic, autophagic and mediated by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:473–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky FM. Antigen processing and presentation: close encounters in the endocytic pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90015-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk UT, Zhang H, Dalen H, Ollinger K. Exposure of cells to nonlethal concentrations of hydrogen peroxide induces degeneration-repair mechanisms involving lysosomal destabilization. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:813–822. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02001-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MR, Karustis DG, Day NA, Honn KV, Sloane BF. Degradation of extracellular-matrix proteins by human cathepsin B from normal and tumour tissues. Biochem J. 1992;282(Pt 1):273–278. doi: 10.1042/bj2820273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch W. The autophagosomal-lysosomal compartment in programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:569–581. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttle DJ, Abrahamson M, Burnett D, Mort JS, Barrett AJ, Dando PM, Hill SL. Human sputum cathepsin B degrades proteoglycan, is inhibited by alpha 2-macroglobulin and is modulated by neutrophil elastase cleavage of cathepsin B precursor and cystatin C. Biochem J. 1991;276:325–331. doi: 10.1042/bj2760325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum JN, Ye Z, Reixach N, Friske L, Levy C, Das P, Golde T, Masliah E, Roberts AR, Bartfai T. Transthyretin protects Alzheimer's mice from the behavioral and biochemical effects of Abeta toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2681–2686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712197105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins CC, Sameni M, Koblinski J, Sloane BF, Moin K. Differential localization of cysteine protease inhibitors and a target cysteine protease, cathepsin B, by immuno-confocal microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:745–751. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins CC, Sloane BF. Mammalian cysteine protease inhibitors: biochemical properties and possible roles in tumor progression. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1995;376:71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catafau AM, Bullich S. Amyloid PET imaging: applications beyond Alzheimer's disease. Clin Transl Imaging. 2015;3:39–55. doi: 10.1007/s40336-014-0098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Nixon RA. Enzymatically active lysosomal proteases are associated with amyloid deposits in Alzheimer brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:3861–3865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Thayer CY, Bird ED, Wheelock TR, Nixon RA. Lysosomal proteinase antigens are prominently localized within senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a neuronal origin. Brain Res. 1990;513:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90456-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart HM, Huang R, Lanham IS, Corder EH, Poduslo SE. Cystatin C as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:755–757. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151980.42337.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman HA, Jr, Reilly JJ, Jr, Yee R, Grubb AO. Identification of cystatin C, a cysteine proteinase inhibitor, as a major secretory product of human alveolar macrophages in vitro. Am Rev Res Dis. 1990;141:698–705. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan VP, Ray I, Chauhan A, Wisniewski HM. Binding of gelsolin, a secretory protein, to amyloid beta-protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;258:241–246. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Leight SN, Lee VM, Li T, Wong PC, Johnson JA, Saraiva MJ, Sisodia SS. Accelerated Abeta deposition in APPswe/PS1deltaE9 mice with hemizygous deletions of TTR (transthyretin) J Neurosci. 2007;27:7006–7010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1919-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DH, Feiner H, Jensson O, Frangione B. Amyloid fibril in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (HCHWA) is related to the gastroentero-pancreatic neuroendocrine protein, gamma trace. J Exp Med. 1983;158:623–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Schapiro R, Kuhn M, Xiong C, Pickering EH, Liu J, Misko TP, Perrin RJ, Bales KR, Soares H, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. Multiplexed immunoassay panel identifies novel CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis and prognosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford FC, Freeman MJ, Schinka JA, Abdullah LI, Gold M, Hartman R, Krivian K, Morris MD, Richards D, Duara R, Anand R, Mullan MJ. A polymorphism in the cystatin C gene is a novel risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2000;55:763–768. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.6.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Duve C. The significance of lysosomes in pathology and medicine. Proc Inst Med Chic. 1966;26:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Duve C, Wattiaux R. Functions of lysosomes. Annu Rev Physiol. 1966;28:435–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.28.030166.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng A, Irizarry MC, Nitsch RM, Growdon JH, Rebeck GW. Elevation of cystatin C in susceptible neurons in alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61781-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodel RC, Du Y, Depboylu C, Kurz A, Eastwood B, Farlow M, Oertel WH, Muller U, Riemenschneider M. A polymorphism in the cystatin C promoter region is not associated with an increased risk of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:664. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MJ. Proteases as prognostic markers in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:613–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn WA., Jr Studies on the mechanisms of autophagy: maturation of the autophagic vacuole. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1935–1945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom U, Wallin H, Lorenzo J, Holmqvist B, Abrahamson M, Aviles FX. Internalization of cystatin C in human cell lines. Febs J. 2008;275:4571–4582. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge R, Iivanainen M, Stern R, Koerber T, Wilder BJ. "Baltic" myoclonus epilepsy: hereditary disorder of childhood made worse by phenytoin. Lancet. 1983;2:838–842. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escrevente C, Morais VA, Keller S, Soares CM, Altevogt P, Costa J. Functional role of N-glycosylation from ADAM10 in processing, localization and activity of the enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filler G, Bokenkamp A, Hofmann W, Le Bricon T, Martinez-Bru C, Grubb A. Cystatin C as a marker of GFR--history, indications, and future research. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finckh U, von Der Kammer H, Velden J, Michel T, Andresen B, Deng A, Zhang J, Muller-Thomsen T, Zuchowski K, Menzer G, Mann U, Papassotiropoulos A, Heun R, Zurdel J, Holst F, Benussi L, Stoppe G, Reiss J, Miserez AR, Staehelin HB, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, Binetti G, Hock C, Growdon JH, Nitsch RM. Genetic association of a cystatin C gene polymorphism with late-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1579–1583. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.11.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S, Kaur G, Mi W, Tizon B, Levy E. Protective mechanisms by cystatin C in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:541–554. doi: 10.2741/s170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Glionna M, Desenzani S, Albertini V, Levy E, Emanuele E, Binetti G. Plasma cystatin C and risk of developing Alzheimer's disease in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:985–991. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Paterlini A, Missale C, Usardi A, Rossi R, Barbiero L, Spano P, Binetti G. Presenilin 2 mutations alter cystatin C trafficking in mouse primary neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidoni R, Paterlini A, Albertini V, Glionna M, Monti E, Schiaffonati L, Benussi L, Levy E, Binetti G. Cystatin C is released in association with exosomes: a new tool of neuronal communication which is unbalanced in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1435–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiso J, Plant GT, Revesz T, Wisniewski T, Frangione B. Familial cerebral amyloid angiopathy (British type) with nonneuritic amyloid plaque formation may be due to a novel amyloid protein. J Neurol Sci. 1995;129:74–75. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)00274-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiso J, Pons-Estel B, Frangione B. Hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy: the amyloid fibrils contain a protein which is a variant of cystatin C, an inhibitor of lysosomal cysteine proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;136:548–554. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaumann H, Ericsson JL, Marzella L. Mechanisms of intralysosomal degradation with special reference to autophagocytosis and heterophagocytosis of cell organelles. Int Rev Cytol. 1981;73:149–182. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard KA, Olson JM, Payami H, Van Der Voet M, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G. Evidence of linkage and association on chromosome 20 for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Neurogenetics. 2004;5:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s10048-004-0174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomperts SN. Imaging the role of amyloid in PD dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14:472. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graffagnino C, Herbstreith MH, Schmechel DE, Levy E, Roses AD, Alberts MJ. Cystatin C mutation in an elderly man with sporadic amyloid angiopathy and intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1995;26:2190–2193. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths G, Gruenberg J. The arguments for pre-existing early and late endosomes. Trends Cell Biol. 1991;1:5–9. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(91)90047-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb AO. Diagnostic value of analysis of cystatin C and protein HC in biological fluids. Clin Nephrol. 1992;38(Suppl 1):S20–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson G, Hallgrimsson J, Jonasson TA, Bjarnason O. Hereditary cerebral haemorrhage with amyloidosis. Brain. 1972;95:387–404. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes CA, Benchimol M, Amarante-Mendes GP, Linden R. Alternative programs of cell death in developing retinal tissue. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41938–41946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan J, Maat-Schieman MLC, van Duinen SG, Jensson O, Thorsteinsson L, Roos RAC. Co-localization of beta/A4 and cystatin C in cortical blood vessels in Dutch, but not in Icelandic hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;89:367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson K, Huh C, Grubb A, Karlsson S, Abrahamson M. Mouse and rat cystatin C: Escherichia coli production, characterization and tissue distribution. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;114:303–311. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(96)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon S, Ford J, Foster J, Dowling L, Lucian L, Sterling M, Xu Y, Weiss M, Ikeda M, Liggett D, Helms A, Caux C, Lebecque S, Hannum C, Menon S, McClanahan T, Gorman D, Zurawski G. Leukocystatin, a new Class II cystatin expressed selectively by hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16400–16408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson SF, Andreasson U, Wall M, Skoog I, Andreasen N, Wallin A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Reduced levels of amyloid-beta-binding proteins in cerebrospinal fluid from Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:389–397. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa A, Naruse M, Hitoshi S, Iwasaki Y, Takebayashi H, Ikenaka K. Regulation of glial development by cystatin C. J Neurochem. 2007;100:12–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helisalmi S, Vakeva A, Hiltunen M, Soininen H. Flanking markers of cystatin c (CST3) gene do not show association with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:318–321. doi: 10.1159/000209278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen H, Datson NA, Ghijsen WE, van Vliet EA, da Silva FH, Gorter JA, Vreugdenhil E. Altered hippocampal gene expression prior to the onset of spontaneous seizures in the rat post-status epilepticus model. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1475–1484. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochwald GM, Pepe AJ, Thorbecke GJ. Trace proteins in biological fluids. IV. Physicochemical properties and sites of formation of gamma trace and beta trace proteins. Proc Soc Exp Med. 1967;124:961–966. doi: 10.3181/00379727-124-31897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung JP, Koppel H, Clarke PG. Endocytosis and autophagy in dying neurons: an ultrastructural study in chick embryos. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:425–437. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseweart MK, Pennacchio LA, Vilaythong A, Peters C, Noebels JL, Myers RM. Cathepsin B but not cathepsins L or S contributes to the pathogenesis of Unverricht-Lundborg progressive myoclonus epilepsy (EPM1) J Neurobiol. 2003;56:315–327. doi: 10.1002/neu.10253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing LC, Rudensky AY. The lysosomal cysteine proteases in MHC class II antigen presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:229–241. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y, Zhao H, Lu X, Kong Y, Jin H. Meta-analysis of the cystatin C(CST3) Gene G73A polymorphism and susceptibility to Alzheimer's disease. Int J Neurosci. 2012 doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.672502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh CG, Hakansson K, Nathanson CM, Thorgeirsson UP, Jonsson N, Grubb A, Abrahamson M, Karlsson S. Decreased metastatic spread in mice homozygous for a null allele of the cystatin C protease inhibitor gene. Mol Pathol. 1999;52:332–340. doi: 10.1136/mp.52.6.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]