Abstract

Background

Young Black men living in resource-poor rural environments are disproportionately affected by both adverse childhood experiences and HIV/STIs. The influence of childhood adversity on sexual risk behavior remains to be examined among this vulnerable population.

Purpose

In this study, we investigated the influence of overall adversity as well as three subcomponents, abusive parenting, parental neglect, and witnessing family violence, on men’s engagement in sexual risk behavior. We hypothesized that adverse experiences would predict engagement in sexual risk behaviors including multiple sexual partnerships, inconsistent condom use, frequent sexual activity, and concurrent substance abuse and sexual activity. We tested formally the extent to which defensive relational schemas mediated these associations.

Methods

Hypotheses were tested with data from 505 rural Black men (M age = 20.29, SD = 1.10) participating in the African American Men’s Health Project. Participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling Self-report data were gathered from participants via audio computer-assisted self-interviews.

Results

Bi-factor analyses revealed that, in addition to a common adversity factor, neglect independently predicted sexual risk behavior. Men’s defensive relational schemas partially mediated the influence of the common adversity factor as well as the neglect subcomponent on sexual risk behavior.

Conclusions

The present research identified a potential risk factor for sexual risk behavior in an understudied and vulnerable population. Adverse childhood experiences in general, and neglect in particular, may place many young Black men at risk for engaging in sexual risk behavior due in part to the influence of these experiences on men’s development of relational schemas characterized by defensiveness and mistrust.

Keywords: Black men, HIV, Risk taking, Adverse childhood experiences, Heterosexual men, Rural environments

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) disproportionately affect young adult Black men. Compared to their Caucasian peers, rates of viral and bacterial STIs are elevated several fold according to epidemiological data (1). These data also indicate that racial disparities in STI rates in rural areas are equal to and, in some cases, exceed those found in densely populated inner cities (2). Studies indicate that STI rates in rural communities are affected by the existence of densely interconnected social networks and a restricted pool of dating partners (3, 4). When condom use is inconsistent and men engage in multiple sexual partnerships, sexual pathogens can spread with particular rapidity in these areas. These risk factors are common among rural Black men (5), underscoring the importance of examining the antecedents of risky sexual behavior in this population.

The young Black men who are the focus of the present study live in small towns and rural communities in Southern Georgia, an area representative of the southern coastal plain that also includes areas of North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi. This area comprises a geographic concentration of rural poverty that coincides with the nation’s worst economic and health disparities by race, including disparities in STIs (6, 7). Growing up in low-SES rural environments places children at heightened risk for exposure to adverse childhood experiences (8). Exposure risk is particularly high among male Black children (9). Adverse childhood experiences include both living in destructive home environments, such as those in which children observe intimate partner violence, and experiencing directly neglectful or abusive treatment from caregivers. These experiences represent extreme environmental hazards to psychosocial and cognitive development (10) and predict a wide range of long-term health outcomes and behaviors during young adulthood, including smoking, substance abuse, psychopathology, and premature death (11).

Emerging research suggests the plausibility of adverse childhood experiences’ predicting rural Black men’s sexual risk behavior. A history of childhood maltreatment has been linked to adult STI infection and involvement in prostitution (12). Hillis and colleagues (13) found a dose-response relationship between adverse childhood experiences and histories of STIs. The vast majority of studies, however, have focused on women, documenting associations of adverse childhood experiences with a range of sexual risk behaviors (14–17) as well as with self-reported STIs (18). Researchers have also begun to explore potential mechanisms linking women’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences with downstream sexual risk vulnerabilities, such as involvement in risky relationships (19), alterations in neurophysiological stress response systems, and substance abuse (20). The extent to which adverse childhood experiences contribute to rural Black men’s sexual risk behavior is unknown.

Although past research supports the plausibility of links between adverse childhood experiences and rural Black men’s risk behavior, the psychosocial mechanisms through which adversity affects men’s risk behavior remain unexamined. Informed by theory and research on enduring beliefs and concomitant behaviors regarding close relationships (21, 22), we hypothesized that adverse childhood experiences’ influence on defensive relational schemas places men at risk for involvement in sexual risk behavior. Relational schemas are cognitive structures that represent patterns of relating within interpersonal contexts (23). Developed in response to one’s history of interpersonal interactions with important others, relational schemas enhance individuals’ ability to define situations efficiently by drawing attention to salient cues in the social environment, goals associated with response options, and consequences associated with particular responses (24). Adverse experiences in family environments are thought to be particularly influential in the development of adults’ processing of information about their current relationships (25). Negative family experiences in general, and harsh parenting during childhood in particular, have been linked to adults’ mistrust of their romantic partners’ motives and to adoption of defensive, cynical, or hostile views of relationships (22). Defensive relational schemas, in turn, are associated with difficulty in engaging in committed romantic relationships (26) as well as with sexual attitudes, substance use before sex, and unprotected intercourse (27). In contrast, individuals with adaptive or secure relational schemas tend to avoid having sex with strangers or engaging in any other sexual activity outside of a committed relationship; they also prefer involvement in mutually initiated sex (27, 28). Studies indicate that defensive relational schemas among African American youth may be characterized by a belief that aggression is necessary to avoid being exploited, cynical views of close relationships, and insecure attachment styles (22, 26, 29). Defensive schemas have been associated with hostile childhood environments (21) and difficulties in establishing monogamous relationships (26, 29).

In the present study, we investigated the effects of both overall adversity and specific subtypes of adverse childhood experiences on men’s sexual risk behavior. Cumulative indices of adversity tend to detect robust effects on health risk behavior (30). Recent research, however, suggests that specific subtypes of adverse experiences may exert differential influences on youth development and risk behavior (31, 32). For example, physical neglect appears to predict internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal) during childhood more strongly than do other types of maltreatment (33). Neglect also appears to be a unique predictor of adult women’s STI history (18). We focused on three forms of childhood adversity. Abusive parenting included physical abuse (intentional injurious behavior) as well as verbal abuse (demeaning and belittling verbal behavior towards a child) by a caregiver. Neglect encompassed a lack of attention to the child’s physical and emotional needs. Witnessing violence towards one’s mother constituted the third adverse experience. Our approach involved investigating both the overall effect of adversity on sexual risk behaviors and the potential for specific forms of adversity to play unique roles in explaining risk behavior. We tested formally the extent to which defensive relational schemas mediated the associations between overall adversity and specific hardships. To control for potential confounding effects from contemporary risk factors associated with both childhood adversity and adult risk behavior, we controlled for men’s student and employment statuses as well as their residence in disadvantaged communities.

Method

Hypotheses were tested with data from 505 men participating in the African American Men’s Health Project, which is a study of health risk behavior, relationship development, and well-being among young Black men. The sample was recruited from 11 contiguous rural counties in southern Georgia. These counties were selected based on their non-urban designation by the U.S. Census Bureau, their population density of less than 100 persons per square mile, and elevated rates of sexually transmitted infections compared to rural areas in other parts of the country (2). Eligibility criteria included self-identification as African American, residence in the sampling area, male gender, and age of 19 to 22 years. Although the focus of the study was on heterosexual men, no attempt was made to screen out men who have sex with men.

Sampling and Recruitment

Participants were recruited using respondent-driven sampling, a chain-referral protocol designed to reduce biases commonly associated with network-based samples (34). This method is preferred for sampling interconnected but hard-to-reach populations (35, 36), such as young Black men whose employment and residential situations change frequently (37). Sampling proceeded as follows. Community Liaisons, respected community members who serve as links between participants and our research center, recruited 45 initial “seed” participants from the 11 sampled counties. The Community Liaisons identified young men through their own social networks and described the study to them. Project staff contacted interested men, described the project, determined eligibility, and set up a data collection visit at the participant’s home or a convenient community site (usually a private room in the public library). Upon completion of the data collection visits, each of the initial “seed” participants provided the names of three men in their personal networks who met eligibility criteria. Project staff contacted these men regarding participation. As with the seeds, upon completion of data collection, these participants also provided referral information for three network members. For each network member successfully recruited into the study, the referring participant received $25.00.

The statistical theory upon which respondent-driven sampling is based suggests that the composition of the sample will stabilize if peer recruitment proceeds through a sufficient number of waves. The sample will become independent of the seeds with whom recruitment began, thereby overcoming any bias that the nonrandom choice of seeds may have introduced. This stable sample composition is called “equilibrium” and should occur within fewer than five recruitment waves. Analyses of the sample using the Respondent-Driven Sampling Analysis Tool (38) indicated that participant recruitment was not biased by the initial seeds’ characteristics on any study variables and that sample equilibrium on all study variables was achieved within two waves of recruitment. Results of t-tests comparing, across all study variables, seed participants and participants who were part of networked referral chains were non-significant, indicating the acceptability of combining seeds with recruited participants in the analyses.

Procedures

Self-report data were gathered from participants via audio computer-assisted self-interviews. The user-friendly program guided respondents through the survey; participants with low literacy were assisted through voice and video enhancements. Each participant received $100 at the conclusion of the data collection visit. Data were gathered from January 2013 through August 2013. All study protocols were approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Sexual risk behavior

Sexual risk behavior during the past 3 months was operationalized as a latent construct using four items. Number of sexual partners was assessed with the item, “In the past 3 months, how many different women or girls have you had sex with?” The response set ranged from 0 (none) to 6 (6 or more). Participants reported the number of times they had vaginal intercourse in the past 3 months on the following scale: 0 (0 times), 1 (1–5), 2 (6–10), 3 (11–20), 4 (21–40), or 5 (41 or more). Inconsistent condom use was indexed with the item, “Of the times you had vaginal sex in the past 3 months, how many times did you use a condom?” The responses ranged from 0 (never) to 5 (every time). This item was reverse coded. Participants reported substance use before sex with the item, “In the past 3 months, how often did you have sex after using alcohol or drugs?” The response ranged from 0 (never) to 5 (every time).

Adverse childhood experiences

Observing violence towards one’s mother, abusive parenting, and neglect were assessed with items from the Adverse Childhood Experiences measure (30, 39). Participants reported whether or not they had particular experiences (yes/no) prior to the age of 16. Abusive parenting was assessed with four items (α = .80; e.g., “During your first 16 years of life did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?”). The neglect scale comprised four items (α = .70; e.g., “During your first 16 years of life did you often or very often feel that your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?”). A three-item maternal abuse scale (α = .78) included: “During the first 16 years of your life, was your mother or stepmother: often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at her?”

Defensive relational schemas

Defensive relational schemas were operationalized as a latent construct using three scales evaluating core aspects of beliefs about relationships associated with Black youth (21, 22). The Street Code measure (40) is a 7-item scale developed to assess the extent to which an individual believes that aggression is a means of gaining respect in relationships. Sample items were, “It is important not to back down from a fight or challenge because people will not respect you,” and “Being viewed as tough and aggressive is important for gaining respect.” Participants’ responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .75. Cynical views of relationships were measured using a four-item scale (22) to assess the degree of suspicion that youth held toward people and relationships. An example item is, “When people are friendly, they usually want something from you.” Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .64. Adult attachment style was assessed with the short form of Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (41). The scale was designed to yield Anxious and Avoidant scores; however, we were unable to replicate this factor structure or obtain reliable subscales as specified. Our factor analysis (available from the corresponding author) revealed a single “negative attachment style” scale that combined both avoidance and anxiety items. The resulting six-item scale attained a Cronbach’s alpha of .74. Example items included, “I often worry that my partner will not want to stay with me” and “I try to avoid getting too close to my romantic partners.” The response set ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).

Demographic characteristics and control variables

During the transition to adulthood, employment status and school status are particularly transitory and difficult to interpret. Thus, scholars studying emerging adulthood suggest that the most important demographic characterization for young men involves simultaneous consideration of employment and student status (42). The goal is to differentiate young people who are gainfully employed or going to school from those involved in neither. In this study, participants who were currently enrolled in school or another educational program or who were employed were coded as “1” and participants who were not enrolled or employed were coded as “0.” The community disadvantage measure comprised 11 items that addressed the occurrence of behaviors in the community such as drinking in public, rape or other sexual assault, and violent arguments between neighbors (43). Participants reported the magnitude of each of these problems in their communities on a scale ranging from 0 (not a problem) to 2 (a big problem). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .90. Men reported their primary caregivers’ education levels on a scale ranging from 1 (Grade 10 or below) to 5 (4-year college degree or more).

Plan of Analysis

Hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling as implemented in Mplus (44) using bi-factor model specifications and the weighted least squares estimator (45). A bi-factor model hypothesizes that (a) a general factor accounts for the commonality shared by the adverse experience items, and (b) multiple specific factors (witnessing maternal violence, abusive parenting, neglect) each accounts for the unique influence of the specific component over and above the general factor. The bi-factor model allowed us to identify forms of adversity that contribute uniquely to sexual risk behavior after the common variance shared with other forms of adversity is taken into account. This provides a uniquely rigorous test of the independent effect of specific forms of adversity. We first specified a measurement model. The bi-factor portion of the model as indicated by items from the Adverse Childhood Experiences measure was constructed with the following features: (a) each item had nonzero loadings on both the general factor and the specific factor that it was designed to measure, but zero loadings on the other specific factors; (b) the specific factors of abusive parenting, neglect, and witnessing maternal violence were uncorrelated with each other and with the general factor; and (c) all error terms associated with the items were uncorrelated. The measurement model also included conventionally constructed latent constructs for defensive relational schemas and sexual risk behaviors. We then executed a model testing the direct effects of general and specific adversity factors on sexual risk behavior, followed by an indirect effect analysis of the mediational influence of defensive relational schemas. Indirect effects were estimated using bootstrapping (46) as implemented in Mplus.

Results

Descriptive information on the study sample is provided in Table 1. The mean age of the men was 20.29 years; 71.3% reported being either employed or in school. The majority of men reported that their caregivers had a high school education. Of the men who reported sexual activity during the past 3 months (n = 430, 85.1%), the mean number of sexual partners during that time was 2.17 and the median frequency of intercourse on the ordinal response scale was 2 (6 – 10 times). Inconsistent condom use was common (58.1%), and 58.1% of men reported using substances during sexual activity. In general, base rates of overall adverse childhood experiences were low (M = 1.79), with abusive parenting being the most commonly reported type of adversity (M = .84)

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics/ Control Variables |

Mean (SD) | N (%) | Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20.29 (1.10) | 20.00 (19 – 22) | |

| School/Employment Status | |||

| Employed or in school | 360 (71.3) | ||

| Not employed or in school | 145 (28.7) | ||

| Community disadvantage | 0.62 (0.50) | 0.55 (0 – 2) | |

| Parental Education | 3.32 (1.04) | 3.00 (1 – 5) | |

| Sexual Risk Behavior | |||

| Sexual Partners | 2.17 (1.80) | 2.00 (0 – 6) | |

| Sexual intercourse frequency | 1.92 (1.64) | 2.00 (0 – 5) | |

| Unprotected Intercourse | 1.47 (1.73) | 1.00 (0 – 5) | |

| Substance Use Before sex | 1.50 (1.51) | 2.00 (0 – 5) | |

| Defensive Relational Schema | |||

| Street Code | 2.68 (0.55) | 2.71 (1 – 4) | |

| Attachment problems | 2.39 (0.59) | 2.33 (1 – 4) | |

| Cynical views of relationships | 2.60 (0.59) | 2.50 (1 – 4) | |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences | |||

| Overall | 1.79 (2.38) | 1.00 (0 – 11) | |

| Abusive parenting | 0.84 (1.28) | 0.00 (0 – 4) | |

| Neglect | 0.61 (1.02) | 0.00 (0 – 4) | |

| Witnessing violence | 0.34 (0.78) | 0.00 (0 – 3) |

The measurement model with all latent constructs fit the data well: χ2 = 169.10, df = 115, χ2/df = 1.47, p = .08, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .98. The standardized factor loadings of the ACE bi-factor model are presented in Table 2. All individual items loaded significantly on a total adversity factor; regarding the adversity sub-factors, items loaded on the expected latent variables significantly and in the expected direction, λ ≥ .35. Indicators of relational schema and STI risk behavior also loaded as expected on their respective constructs.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the ACE bi-factor measurement model (N = 505)

| Adverse Childhood Events Scale Items | Counts (%) | General λ (SE) |

Abusive parenting λ (SE) |

Neglect λ (SE) |

Witnessing violence to mother λ (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Adults swore at you, insulted you, put you down. | 144 (28.5) | .73 (.07) | .51 (.16) | ||

| 2. | You were afraid that you might be physically hurt. | 82 (16.2) | .78 (.08) | .49 (.17) | ||

| 3. | Adults pushed, grabbed, slapped, or threw something at you. | 122 (24.2) | .81 (.06) | .35 (.14) | ||

| 4. | Adults hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured. | 76 (15.0) | .90 (.06) | .35 (.16) | ||

| 5. | You felt no one in your family loved you. | 99 (19.6) | .50 (.07) | .66 (.08) | ||

| 6. | You felt your family didn’t look out for each other. | 119 (23.6) | .49 (.07) | .65 (.08) | ||

| 7. | You didn’t have enough to eat, wore dirty clothes. | 60 (11.9) | .65 (.07) | .54 (.09) | ||

| 8. | Your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you. | 29 (5.7) | .66 (.09) | .58 (.11) | ||

| 9. | Your mother was pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at her. |

84 (16.6) | .67 (.07) | .86 (.09) | ||

| 10. | Your mother was kicked, bitten, or hit with a fist. | 62 (12.3) | .68 (.07) | .58 (.10) | ||

| 11. | Your mother was hit repeatedly or threatened/injured with a weapon. |

24 (4.8) | .73 (.08) | .49 (.12) |

Note. All factor loadings are significant (p < .01).

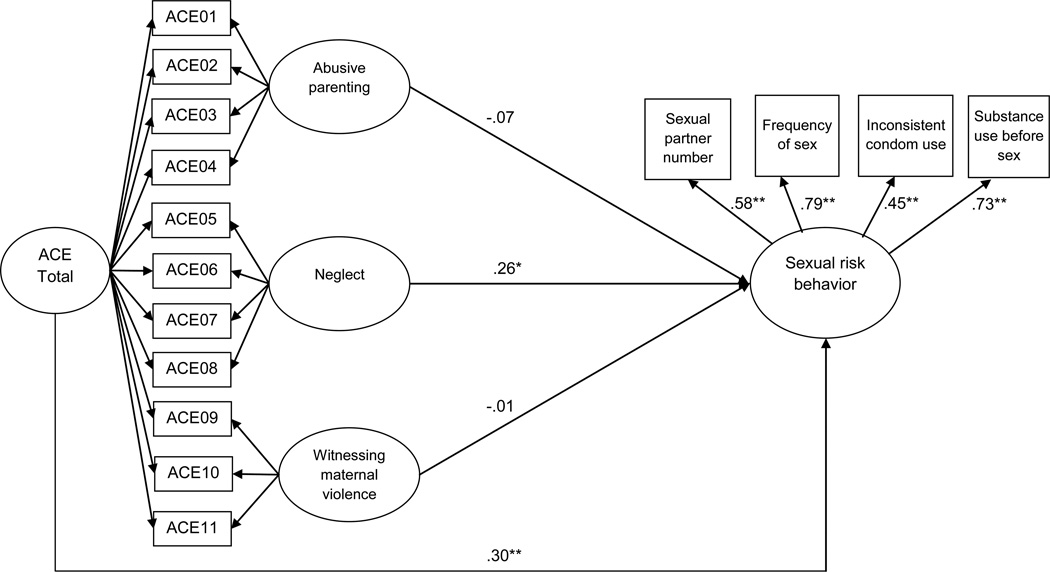

We next tested a bi-factor model linking sexual risk behavior to the general adversity component and each adversity subcomponent. This model, presented in Figure 1, fit the data well: χ2 = 204.10, df = 117, p = .01, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .98; R2 = .12). In the bi-factor context, the common factor representing overall adversity was a direct predictor of sexual risk behavior (β = .30, p < .01). Among the specific adversity subcomponents, only neglect significantly predicted sexual risk behavior (β = .26, p < .05). Among the control variables, community disadvantage predicted sexual risk behavior (β = .17, p < .01; not pictured); school/employment status was not associated with the outcome.

Figure 1.

Bi-factor model of adverse childhood experiences’ effects on sexual risk behavior. Standardized coefficients are shown. Youth age, school enrollment/employment status, and community disadvantage were controlled. ACE = adverse childhood experiences.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

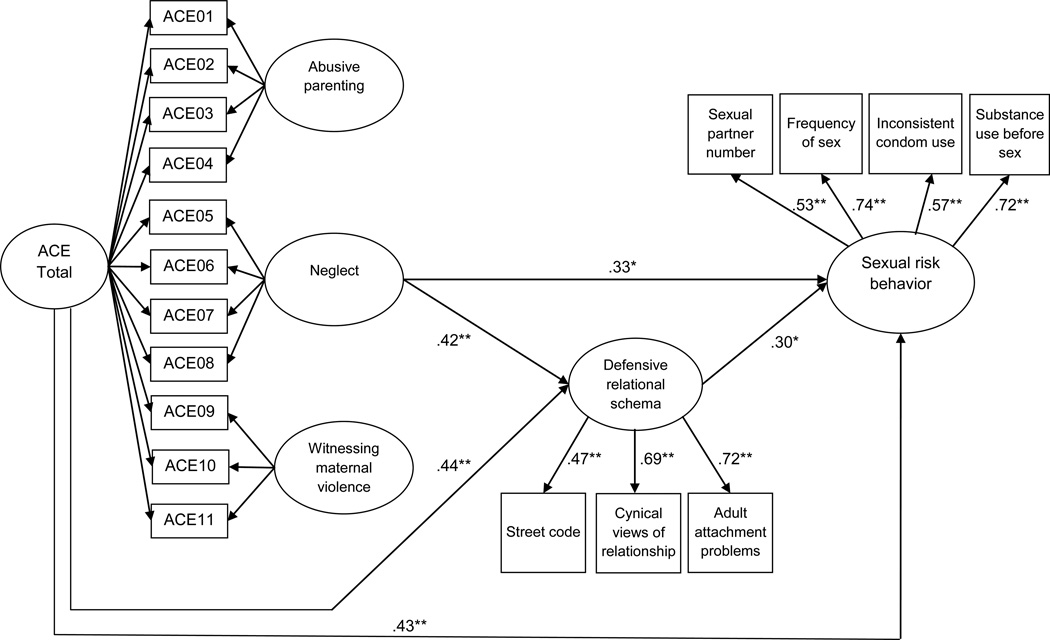

Figure 2 presents the indirect effect of defensive relational schema; non-significant pathways were deleted from the presentation of the final model. The model fit the data well: χ2 = 204.76, df = 163, p = .02, RMSEA = .02, CFI = .99. The overall adversity component (β = .44, p < .01) and the neglect subcomponent (β = .42, p < .01) significantly predicted defensive relational schemas (R2 = .21), which in turn significantly predicted sexual risk behavior (β = .30, p = .05; R2 = .14). Of the control variables, community disadvantage predicted both sexual risk behavior (β = .17, p < .01) and defensive schemas (β = .18, p < .01); school/employment status was not associated with either outcome.

Figure 2.

Bi-factor model predicting indirect associations through defensive relational schemas. Standardized coefficients are shown. Nonsignificant pathways are not pictured. Youth age, school enrollment/employment status, and community disadvantage were controlled. ACE = adverse childhood experiences.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Indirect effect analyses revealed that the associations of the overall adversity component with sexual risk behavior were partially mediated by relational schemas, b = .15, 95% CI [.018, .287]; this was also true for the neglect subcomponent, b = .14, 95% CI [.041, .242]. In addition to indirect effects through relational schemas, there remained direct effects on sexual risk behavior for both the general adversity component (β = .43, p < .01) and the neglect subcomponent (β = .33, p < .05).

Discussion

To date, little research has investigated empirically the influence of childhood adversity on sexual risk behavior among Black men in general and those living in rural areas in particular. In this study, we examined the influence of a general adversity component as well as three adversity subcomponents: witnessing family violence, abusive parenting, and neglect. Bi-factor analyses revealed that, in addition to a common adversity factor, neglect independently predicted sexual risk behavior. Men’s negative relational schemas partially mediated the influence of the common adversity factor and the neglect subcomponent on sexual risk behavior.

Our findings are consistent with studies documenting associations between adverse childhood experiences and a range of downstream health risk behaviors (11), including self-reported STIs (13). The majority of research to date linking childhood adversity to risky sexual behavior, however, has focused on women. Study findings suggest that adversity in general, and neglect in particular, are important experiences that may shape Black men’s sexual risk behavior in young adulthood. These findings are consistent with studies of male and female samples in which adversity was linked to HIV and other self-reported STIs (12, 13). In contrast, our findings are inconsistent with Haydon et al. (18), who found that maltreatment predicted women’s, but not men’s, laboratory-assessed STI history. Considerable differences in measurement and sample composition make this inconsistency difficult to interpret. Further research is needed with samples composed of both men and women to examine the ways in which gender may modulate the influence of adversity.

A bi-factor analytic approach allowed us to examine the influence of total adversity versus specific forms of adversity. The general adversity factor in our results captures the total effect of exposure to abusive parenting, neglect, and witnessing violence; it had a robust effect on both defensive relational schemas and sexual risk behavior. The strength of this association is consistent with past research that emphasizes the cumulative impact of multiple forms of adversity (47). Studies reveal that children often contend with constellations of risk rather than isolated instances or forms of adverse circumstances. The preponderance of evidence indicates that multiple, relative to single, risk exposures have worse developmental and health related consequences for children and youth; present study findings are consistent with this perspective (48).

The bi-factor modeling approach allowed for a uniquely rigorous evaluation of the impact of specific forms of adversity. The general adversity factor may be conceptualized as an index of men’s total childhood exposure to stressful experiences in the social environment. This factor does not include the specific contexts and family-related behaviors that are causing stress. The specific impact of neglect, however, is indexed with the overall toxicity of the environment taken into account. The significant findings for the influence of neglect are thus of particular interest, given that they explained unique variance in the outcome independent of the influence of overall stress or toxicity in the environment. The importance of neglect to sexual risk behavior is consistent with a growing body of research suggesting that—like other forms of child maltreatment—childhood neglect poses a considerable threat to subsequent health behavior (49–51). Results also suggest that neglected persons may suffer adverse consequences that are unique to the experience of neglect rather than those common to victims of general childhood/adolescent maltreatment. Neglect involves a lack of mutual interaction between a child and his caretaker, depriving the child of a source of support that is critical to development (52). The lack of stimulation and interaction may be more pervasive in neglectful families than in families in which a child experiences other forms of maltreatment, such as abusive parenting. Researchers have surmised that physical contact occurring in the form of abuse may be less harmful than no contact at all (i.e., neglect) because such parents may be less emotionally detached and disinterested in their infants and may be somewhat more likely to respond to their children’s important signals than neglectful parents (53). Alternatively, physically abused children, although confronted with parenting dysfunction, may experience periods during which they are responded to, possibly even positively, by their physically abusive parents. Thus, it may well be that physically abused children are more likely to develop personal agency and positive aspects of the self, whereas neglected children have far fewer opportunities to do so (54).

Indirect effect analyses indicated that neglect predicted men’s negative relational schemas, expectations for close relationships characterized by defensiveness, anxiety, and mistrust. These schemas, in turn, predicted sexual risk behavior. This finding is consistent with past research indicating that neglect disrupts the formation of secure attachments to caregivers; this, in turn, affects relational schemas into adulthood (55). Studies also have identified the mediating role of relational schemas in linking childhood adversity to a range of problematic adult outcomes, including psychological distress, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms (52, 56, 57).

Our findings extend this research base and underscores the role of relational schemas as a mediator of the effects of adversity on risky sexual behavior. Little research to date has considered that men’s engagement in risky sex and multiple partnerships may be a product of their relational schemas. Currently, efforts to intervene with sexual risk behaviors essentially exclude the quality of men’s romantic relationships with women and focus on developing efficacy and self-regulation in regards to protective sexual behavior. Our findings suggest that intervention efforts may also need to focus on the sense that men make of relationships in general and the power of past experiences to inculcate a sense of mistrust and defensiveness in close relationships.

Although relational schemas accounted for a portion of the effect of general adversity and neglect and on sexual risk behavior, robust main effects remained. This suggests that other psychosocial mechanisms are important in understanding these pathways. One potential mediator for examination in future studies is alcohol and drug abuse, which has been linked with cumulative indices of adversity (58) and neglect (59, 60) and is a robust proximal predictor of sexual risk behaviors.

We also acknowledge several limitations regarding the interpretation of these findings. Adverse childhood experiences were based upon retrospective self-report and were relatively low compared with published reports (8); respondents may have been reluctant to disclose maltreatment histories. In the African American Men’s Health Project, we attempted to minimize underreporting by administering maltreatment questions via computer-assisted self-interviewing technology, which increases valid responding to sensitive questions. Low rates and a restricted range of adverse childhood experiences also may lead to an underestimation of the effects of these experiences on relational schema and sexual risk behavior. Our analyses also excluded sexual abuse. Although this was a low base rate event in our sample, it has been identified as a significant risk factor for sexual risk behavior in young men (61). Finally, our sample focused on young Black men living in rural areas of South Georgia. The extent to which these findings generalize to young men living in other areas is unknown.

These limitations notwithstanding, the present research illuminated a potential risk factor for sexual risk behavior in an understudied and vulnerable population. Black men in these areas experience disproportionate levels of adverse experiences during childhood and adolescence. These adverse childhood experiences in general, and neglect in particular, may place many young men at risk for engaging in sexual risk behavior due in part to the influence of these experiences on men’s development of relational schemas characterized by defensiveness and mistrust.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number R01 DA029488 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Eileen Neubaum-Carlan, MS, for her helpful comments in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Drs. Kogan, Cho, and Oshri have no potential conflicts of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at the University of Georgia and the American Psychological Association. The research also complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2013. [Accessibility verified October 16, 2015]; Available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats13/default.htm.

- 2.Chesson HW, Kent CK, Owusu-Edusei K, Jr, Leichliter JS, Aral SO. Disparities in sexually transmitted disease rates across the “eight Americas”. Sex Transm. Dis. 2012;39:458–464. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318248e3eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm. Dis. 2006;33:S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesson H, Owusu-Edusei K, Kent C, Aral S. STD rates in the eight Americas: Disparities in the burden of syphilis, gonorrhoea, and chlamydia across race and county. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:A195. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kogan SM, Cho J, Barnum S, Brown GL. Correlates of sexual partner concurrency among rural African American men. Public Health. Rep. 2015;130:392–399. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1675–1679. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wimberly RC, Morris LV. The Southern Black Belt: A national perspective. Lexington, KY: TVA Rural Studies Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Resources and Services Administration. The health and well-being of children in rural areas: A portrait of the nation 2007. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umberson D, Williams K, Thomas PA, Liu H, Thomeer MB. Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2014;55:20–38. doi: 10.1177/0022146514521426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogosch FA, Dackis MN, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment and allostatic load: Consequences for physical and mental health in children from low-income families. Dev Psychopathol. 2011;23:1107–1124. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalmakis KA, Chandler GE. Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27:457–465. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health Psychol. 2008;27:149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: A retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E11. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke TF, Newcomb MD. Correlates and predictors of HIV risk among inner-city African American female teenagers. Health Psychol. 2008;27:337–348. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messman-Moore TL, Walsh KL, DiLillo D. Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senn TE, Carey MP. Child maltreatment and women’s adult sexual risk behavior: Childhood sexual abuse as a unique risk factor. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:324–335. doi: 10.1177/1077559510381112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Child sexual abuse, HIV sexual risk, and gender relations of African-American women. Am J Prev. Med. 1997;13:380–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haydon AA, Hussey JM, Halpern CT. Childhood abuse and neglect and the risk of STDs in early adulthood. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43:16–22. doi: 10.1363/4301611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson HW, Widom CS. Pathways from childhood abuse and neglect to HIV-risk sexual behavior in middle adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:236–246. doi: 10.1037/a0022915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social enviornments and the mental and physcial health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simons RL, Burt CH. Learning to be bad: Adverse social conditions, social schemas, and crime. Criminology. 2011;49:553–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons RL, Simons LG, Lei MK, Landor AM. Relational schemas, hostile romantic relationships, and beliefs about marriage among young African American adults. J Soc Pers Relationships. 2012;29:77–101. doi: 10.1177/0265407511406897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldwin MW. Relational schemas and cognition in close relationships. J Soc Pers Relationships. 1995;12:547–552. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy A, Steele M, Dube SR, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) questionnaire and adult attachment interview (AAI): Implications for parent child relationships. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kogan SM, Lei MK, Grange CR, et al. The contribution of community and family contexts to African American young adults' romantic relationship health: A prospective analysis. J Youth Adolescence. 2013;42:878–890. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9935-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feeney JA, Peterson C, Gallois C, Terry DJ. Attachment style as a predictor of sexual attitudes and behavior in late adolescence. Psychol Health. 2000;14:1105–1122. doi: 10.1080/08870440008407370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:267–283. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons LG, Simons RL, Landor AM, Bryant CM, Beach SRH. Factors linking childhood experiences to adult romantic relationships among African Americans. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28:368–379. doi: 10.1037/a0036393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev. Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Gunnar MR, Toth SL. The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school-aged children. Child. Dev. 2010;81:252–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oshri A, Sutton TE, Clay-Warner J, Miller JD. Child maltreatment types and risk behaviors: Associations with attachment style and emotion regulation dimensions. Pers Individ. Dif. 2015;73:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence—24 Cities, United States, 2006–2007. JAMA. 2011;306:1320–1322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malekinejad M, Johnston LG, Kendall C, et al. Using respondent-driven sampling methodology for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in international settings: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:S105–S130. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kogan SM, Wejnert C, Chen Y-F, Brody GH. Respondent-driven sampling with hard-to-reach emerging adults: An introduction and case study with rural African Americans. J Adolesc. Res. 2010;26:30–60. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volz E, Wejnert C, Degani I, Heckathorn DD. Respondent-Driven Sampling Analysis Tool (RDSAT) Ithaca, NY: Cornell University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart EA, Simons RL. Structure and culture in African American adolescent violence: A partial test of the"code of the street" thesis. Justice Q. 2006;23:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Vogel DL. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 2007;88:187–204. doi: 10.1080/00223890701268041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wald M, Martinez T. Connected by 25: Improving the life chances of the country's most vulnerable 14–24 year olds; William and Flora Hewitt Foundation Working Paper; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen FF, Hayes A, Carver CS, Laurenceau JP, Zhang Z. Modeling general and specific variance in multifaceted constructs: a comparison of the bifactor model to other approaches. J Pers. 2012;80:219–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JP. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seery MD, Holman EA, Silver RC. Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99:1025–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0021344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:1342–1396. doi: 10.1037/a0031808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kendall-Tackett KA, Eckenrode J. The effects of neglect on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: A developmental perspective. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snyder SM, Merritt DH. The influence of supervisory neglect on subtypes of emerging adult substance use after controlling for familial factors, relationship status, and individual traits. Subst Abus. 2015;36:597–514. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.997911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trickett PK, McBride-Chang C. The developmental impact of different forms of child abuse and neglect. Dev. Rev. 1995;15:311–337. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gauthier L, Stollak G, Messé L, Aronoff J. Recall of childhood neglect and physical abuse as differential predictors of current psychological functioning. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20:549–559. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Emde RN. Representations of self and other in the narratives of neglected, physically abused, and sexually abused preschoolers. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9:781–796. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Egeland B, Sroufe LA. Attachment and early maltreatment. Child. Dev. 1981;52:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hildyard KL, Wolfe DA. Child neglect: Developmental issues and outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:679–695. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Styron T, Janoff-Bulman R. Childhood attachment and abuse: Long-term effects on adult attachment, depression and conflict resolution. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:1015–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Twaite JA, Rodriguez-Srednicki O. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult vulnerability to PTSD: The mediating effects of attachment and dissociation. J Child Sex Abuse. 2004;13:17–38. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Jr, Gore S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: A longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afifi TO, Henriksen CA, Asmundson GJG, Sareen J. Childhood maltreatment and substance use disorders among men and women in a nationally representative sample. Canadian J Psychiatry. 2012;57:677–686. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faulkner B, Goldstein AL, Wekerle C. Pathways from childhood maltreatment to emerging adulthood: Investigating trauma-mediated substance use and dating violence outcomes among child protective services–involved youth. Child Maltreat. 2014;19:219–232. doi: 10.1177/1077559514551944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Homma Y, Wang N, Saewyc E, Kishor N. The relationship between sexual abuse and risky sexual behavior among adolescent boys: A meta-analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]