Abstract

Spontaneous co-speech hand gestures provide a visuospatial representation of what is being communicated in spoken language. Although it is clear that gestures emerge from representations in memory for what is being communicated (De Ruiter, 1998; Wesp, Hesse, Keutmann, & Wheaton, 2001), the mechanism supporting the relationship between gesture and memory is unknown. Current theories of gesture production posit that action – supported by motor areas of the brain – is key in determining whether gestures are produced. We propose that when and how gestures are produced is determined in part by hippocampally-mediated declarative memory. We examined the speech and gesture of healthy older adults and of memory-impaired patients with hippocampal amnesia during four discourse tasks that required accessing episodes and information from the remote past. Consistent with previous reports of impoverished spoken language in patients with hippocampal amnesia, we predicted that these patients, who have difficulty generating multifaceted declarative memory representations, may in turn have impoverished gesture production. We found that patients gestured less overall relative to healthy comparison participants, and that this was particularly evident in tasks that may rely more heavily on declarative memory. Thus, gestures do not just emerge from the motor representation activated for speaking, but are also sensitive to the representation available in hippocampal declarative memory, suggesting a direct link between memory and gesture production.

1. Introduction

When we talk, we gesture with our hands. Our hand gestures are both temporally and semantically related to the speech that they accompany (McNeill, 1992). Hand gestures facilitate communication for the speaker and for the listener (e.g., Hostetter, 2011) and enhance memory and learning (Cook, Yip, & Goldin-Meadow, 2010; Feyereisen, 2006). But, where do gestures come from? Although it seems intuitive that gestures emerge from representations in memory (De Ruiter, 1998; Wesp et al., 2001), the mechanism supporting functional links between gesture and memory is unknown. The current study is part of a broader line of work bringing together the empirical study of gesture and of multiple memory systems (Klooster, Cook, Uc, & Duff, 2015). Here, we test the hypothesis that gesture is supported by hippocampal declarative memory representations, providing a starting point for the investigation of the neural and cognitive mechanisms linking gesture and memory.

Gestures reflect our thoughts iconically (Hilliard & Cook, 2015). Mental representations in the mind are translated into gestures, with the hands conveying a global and imagistic form of the message being communicated (McNeill, 1992). For example, when asked to describe how to make a sandwich, the speaker is likely to bring to mind a rich, multi-faceted representation including, but not limited to, the ingredients needed to make the sandwich, the actions required and the temporal sequence of these actions, general semantic information about sandwich making, and autobiographical memories of previous contexts and occasions for making specific sandwiches. Relevant information will then be expressed in speech and in gesture.

As an initial attempt at understanding the nature of memory representations supporting gesture we investigated the hippocampal declarative memory system. The hippocampus and other medial temporal lobe structures have long been linked to the formation and subsequent retrieval of enduring (long-term) memory (Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2001; Gabrieli, 1998; Squire, 1992). The hippocampus plays a central role in support of relational (or associative) memory binding (Davachi, 2006; Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2001; Ryan, Althoff, Whitlow, & Cohen, 2000) which permits long-term encoding of the co- occurrences of people, places, and things along with the spatial, temporal, and interactional relations among them (see Konkel & Cohen, 2009) that constitute events, as well as representations of relationships among events across time, providing the basis for the larger record of one’s experience. Another hallmark of the hippocampal declarative (relational) memory system is its representational flexibility, which permits the reconstruction and recombination of information and allows such information to be used in novel situations and contexts (Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2001). Hippocampal relational representations have also been implicated in supporting flexible cognition more broadly with hippocampal declarative memory deficits negatively impacting aspects of language and communication, decision making, and social cognition (for review see Rubin, Watson, Duff, & Cohen, 2014). Taken together, the role of the hippocampus in relational binding and representational flexibility supports our ability to reconstruct and recreate richly detailed, multimodal, memories of our remote past, our ability to imagine events and scenarios of our distant futures, and to flexibly act in and on the world. If gesture emerges from rich, relational memories, then gestures may depend on hippocampal representations.

When asked to construct and narrate a memory from their real past or to imagine what might happen in the future, patients with bilateral hippocampal damage and severe declarative memory impairment produce significantly fewer episodic details (e.g., Hassabis, Kumaran, Vann, & Maguire, 2007; Kurczek et al., 2015; Race, Keane, & Verfaellie, 2011). That is, the verbal descriptions of past and future events of patients with hippocampal amnesia are impoverished, containing fewer details about the people, places, and things, as well as the spatial and temporal aspects of their experiences. But what about the information that is conveyed in gesture? Do disruptions in hippocampal declarative memory representation extend to gesture? That is the question we address here.

Although prior work has not directly tested the relationship between hippocampal memory representations and gesture, there is evidence for a link between working memory and the production of gesture. Producing gesture during communication can reduce the burden on working memory (Cook, Yip, & Goldin-Meadow, 2012; Goldin-Meadow, Nusbaum, Kelly, & Wagner, 2001). Moreover, lower scores on working memory tasks in healthy individuals are predictive of higher gesture rates (Gillespie, James, Federmeier, & Watson, 2014). These findings, coupled with work suggesting that gesture may aid in retrieval of words during discourse (Krauss, Chen, & Gottesman, 2000) and on vocabulary tests (Nooijer, van Gog, Paas, & Zwaan, 2013), indicate that people gesture more when memory demands are higher. It is unclear, however, if such patterns would be observed in patients with hippocampal amnesia, who can perform normally on standardized tasks of working memory but who also can exhibit deficits on relational memory tasks over very short delays (i.e., on the time scale of traditional working memory tasks) (e.g., Hannula, Tranel, & Cohen, 2006).

The information in gesture is sometimes also expressed in the accompanying speech and is sometimes unique to gesture (Alibali, Kita, & Young, 2000; Cassell, McNeill, & McCullough, 1998; Goldin-Meadow, 1999). For example, when describing making a sandwich, a speaker might say, “And, then you put the mustard on the bread,” and accompany this description with either a spreading motion or a squeezing motion, depending on the type of mustard that the speaker has in mind. In this case, gesture expresses unique information, although if the speaker had instead chosen to say “squeeze” or “spread” the information in speech and gesture would have been the same. Because gesture and speech sometimes convey the same information and sometimes convey different, but complementary, information, it is not clear that the impoverished episodic representations observed in verbal descriptions in patients with hippcampal amnesia will extend to their gestures. Gesture may emerge directly from aspects of declarative (episodic) memory representations, or may emerge from memory representations that are not hippocampally mediated. Studies of healthy participants cannot reliably implicate specific memory systems as both systems are intact and possibly engaged, even in implicit tasks or processing. An alternative approach to test ideas about the relationship between memory and gesture is to examine co-speech gesture in neurological patients who have specific types of memory impairment.

We examined gesture production in a group of patients with severe declarative memory impairment (and intact procedural memory) due to bilateral hippocampal damage. Patients and comparison participants completed four discourse tasks: how to go shopping in an American supermarket, how to make their favorite sandwich, their most frightening experience, and how they heard about JFK’s assassination. While hippocampal declarative memory has long been defined in terms of its capacity for supporting rich, relational, and multimodal mental representations, the current study is the first to examine gesture production in the communication of patients with severe hippocampal amnesia. If hippocampal functioning supports gesture production, then we would expect the co-speech gestures of patients with hippocampal amnesia to differ in some way (e.g., fewer gestures) from those of demographically matched comparison participants, particularly when describing events that have the most episodic features and thus require more hippocampal reconstruction. But if gesture just comes along with speech regardless of the underlying representation, or via non-hippocampally mediated representations, we might expect that gesture is unaffected by hippocampal damage and thus independent of the hippocampal declarative memory system.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

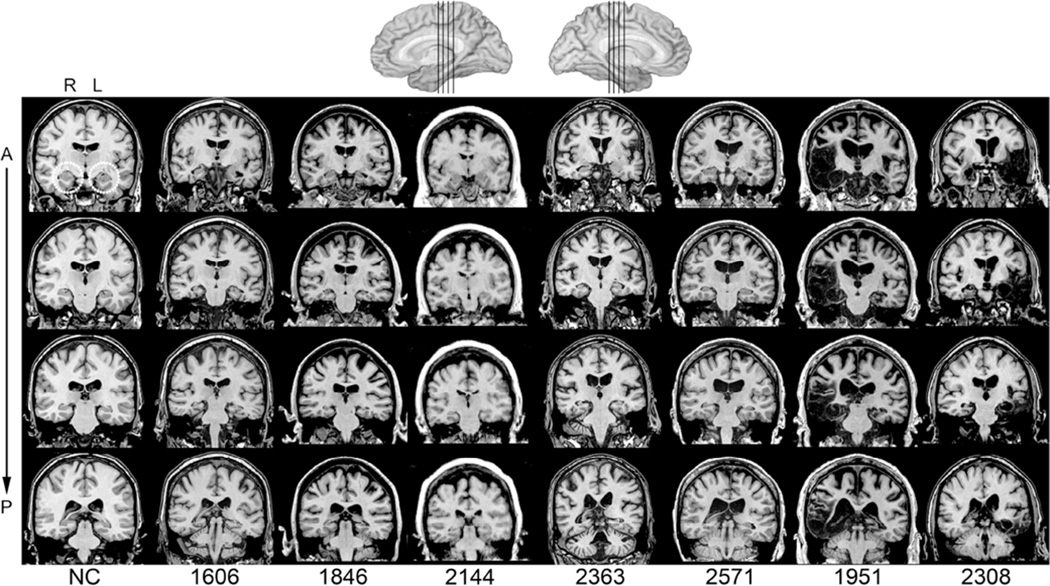

Eighteen people participated in the study: nine individuals with bilateral hippocampal damage and severe declarative memory impairment (four females; seven right handed) and nine healthy adult participants (four females; seven right handed). At the time of data collection, the patients with amnesia were medically stable and in the chronic epoch of amnesia, with time-post-onset ranging from 1 to 25 years (M = 9.33; SD = 7.1). The patients were on average 50 years old (range 42–58) and had 14 years of education (range 9–16). Etiologies included anoxia/hypoxia (001, 1606, 1846, 2144, 2363, 2563, 2571), resulting in bilateral hippocampal damage, and herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) (1951, 2308), resulting in more extensive bilateral medial temporal lobe damage affecting the hippocampus, amygdala, and surrounding cortices (Figure 1). High-resolution volumetric MRI data were available for six patients (excluding 001, 2563, 2308) and revealed significant reduction to the hippocampus bilaterally with volumes reduced by at least 1.01 studentized residuals compared to age matched healthy comparison participants. The average reduction for the anoxic participants was 3.16 studentized residuals, compared to healthy participants. MRI images for 001 are published and reveal bilateral hippocampal volume reductions (D. E. Hannula et al., 2006). Visual inspection of a CT scan from patient 2563, who wears a pacemaker, confirmed damage limited to hippocampus. Extensive bilateral medial temporal lobe damage in patient 2308 can be visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance scans of hippocampal patients. Images are coronal slices through four points along the hippocampus from T1-weighted scans. R = right; L = left; A = anterior; P = posterior; NC = a healthy comparison brain.

Performance on tests of neuropsychological functioning revealed a severe and selective impairment in declarative memory functioning while performance across other cognitive domains was within normal limits (see Table 1). The Wechsler Memory Scale–III General Memory Index scores for each participant were at least 25 points lower than their scores on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III, and the mean difference between Full Scale IQ and General Memory Index was 34.8 points. The average Delayed Memory Index was 63.3, almost 3 standard deviations below population means. This deficit in declarative memory was observed in the context of otherwise intact cognitive abilities. Participants performed within normal limits on standardized neuropsychological tests of intelligence, language, and executive function and experimental measures of non-declarative or procedural memory (Cavaco, Anderson, Allen, Castro-Caldas, & Damasio, 2004). The patients with hippocampal amnesia do not have aphasia as determined by standardized neuropsychological assessments of language and determination of a speech-language pathologist. All participants were monolingual speakers of American English and no participants had mobility or motoric deficits that would interfere with physically producing gestures. These patients are well known to our group as we have studied their memory and language abilities for over a decade (e.g., Duff & Brown-Schmidt, 2012). Across a range of tasks, we have repeatedly documented deficits in declarative memory representations (e.g., Duff, Hengst, Tranel, & Cohen, 2007; Klooster & Duff, 2015; Konkel et al., 2008; Kurczek et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Demographic, neuroanatomical, and neuropsychological characteristics of participants with hippocampal amnesia

| Subject | Sex | Age | Hand | Ed | Etiology | HC Damage |

HC Volume |

WMS III GMI |

WAIS III FSIQ |

BNT | TT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | F | 54 | R | 9 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

N/A | 54 | 90 | 56 | 44 |

| 1606 | M | 55 | R | 12 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

−3.99 | 66 | 91 | 32 | 44 |

| 1846 | F | 46 | R | 14 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

−4.23 | 57 | 84 | 43 | 41 |

| 2144 | F | 53 | R | 12 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

−3.92 | 56 | 99 | 56 | 44 |

| 2363 | M | 46 | R | 18 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

−2.64 | 73 | 98 | 58 | 44 |

| 2563 | M | 47 | L | 16 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

N/A | 75 | 102 | 52 | 44 |

| 2571 | F | 39 | R | 16 | Anoxia | Bilateral HC |

−1.01 | 87 | 112 | 58 | 44 |

| 1951 | M | 50 | R | 16 | HSE | Bilateral HC +MTL |

−8.10 | 57 | 121 | 49 | 44 |

| 2308 | M | 46 | L | 16 | HSE | Bilateral HC +MTL |

N/A | 45 | 87 | 52 | 44 |

|

HC Mean |

4F 5M |

48.4 (±5.1) |

7R 2L |

14.3 (±2.8) |

63.3 (±13.0) |

98.2 (±12.1) |

50.7 (±8.5) |

43.6 (±1.0) |

Note: Hand.=Handedness. Ed.=years of completed education. HSE=Herpes Simplex Encephalitis. HC=hippocampus. +MTL=damage extending into the greater medial temporal lobes. N/A=no available data. Volumetric data are z-scores as measured through high resolution volumetric MRI and compared to a matched healthy comparison group (see Allen, Tranel, Bruss, & Damasio, 2006, for additional details). WMS-III GMI=Wechsler Memory Scale–III General Memory Index. WAIS-III FSIQ=Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III Full Scale Intelligence Quotient. BNT=Boston Naming Test. TT=Token Test. Bolded scores indicate significant normative impairment.

The healthy participants served as demographically matched comparison participants to the patients with amnesia and matched the patients on age, sex, education, and handedness. At the time of the study, these healthy participants were, on average, 50.6 years old (SD = 6.1) and had 14.4 (SD = 2.4) years of education, on average. All healthy comparison participants were free of neurological and psychological disease.

2.2. Procedures

The current study is a reanalysis of a data set previously collected using the Mediated Discourse Elicitation Protocol (MDEP) (Hengst & Duff, 2007). The data were originally collected to investigate the hippocampal contributions to spoken language and discourse (e.g., Duff et al., 2007; Duff, Hengst, Tranel, & Cohen, 2009). Here, we return to these data to address the novel question of hippocampal contributions to gesture production. The MDEP was designed to collect ecologically valid, interactional samples of multiple types of discourse following conventions in the literature (Cherney, Coelho, & Shadden, 1998). For the current study, four narrative discourse tasks were analyzed: two procedural discourse narratives (how to make a favorite sandwich and how to grocery shop in an American supermarket) and two episodic/autobiographical narratives (their most frightening experience and their account the JFK’s assassination). We chose narrative samples (over conversational samples) as narratives (of real or imagined events) are among the best studied discourse forms in the memory literature (Hassabis et al., 2007; Kurczek et al., 2015; Levine, Svoboda, Hay, Winocur, & Moscovitch, 2002; Race et al., 2011) as well as in the gesture literature (McNeill, 1992). Participants conversed with an experimenter (author M.D.) who was blind to hypotheses concerning gesture production as we were not studying gesture at the time of data collection. Prior to the discourse sampling sessions, participants were instructed that they would be talking about different topics, much like they do in their everyday conversations; there would be no right or wrong answers and they should try to communicate as naturally as possible.

The experimenter provided prompts for each discourse topic. For the first two topics, the prompts were “I want you to tell me about your most frightening experience,” and “I want you to tell me where you were and how you learned about JFK’s assassination.” For the last two topics, the prompts were “Tell me how to make your favorite sandwich” and “I want you to pretend I’m from Timbuktu. Tell me everything I need to know about shopping in an American grocery store.” Tasks were always presented in the order outlined above. While the participant spoke, the experimenter provided appropriate conversational feedback (e.g., verbal and non-verbal backchannels such as “uh huh”, “I see”, and “that’s great”). For the procedural discourse narratives, the examiner also took notes while nodding and providing this feedback. The participant could speak as much or as little as deemed necessary. The instructions did not mention gesture, and the experimenter was not investigating gesture at the time of data collection and so did not explicitly attend to participant’s gesture. However, the video recording of the sessions provided appropriate capture of gesture to support the current coding and analysis.

2.3. Coding

Speech was transcribed from the videos. For each discourse topic, a total word count was calculated from the transcripts to assess the amount of speech and allow for a calculation of gesture rate (total gestures divided by total words produced). All hand movements that accompanied speech were coded as gestures using ELAN (EUDICO Linguistic Annotator; Lausberg & Sloetjes, 2009). Each gesture was categorized as one of three gesture types: iconic, deictic, and beat. Iconic gestures resembled the word or concept that was being communicated. For example, saying the word “up” while moving the hand upwards or saying the word house while making a triangle out of the hands to represent a roof. Beat gestures were simple movements that carried no semantic content and were produced in rhythm with speech. Deictic gestures were typically pointing gestures that referred to something in space. Because the conversations were about past events or things that were not visually present, deictic gestures were relatively infrequent in this dataset. Still, participants would occasionally use a pointing gesture to refer to themselves or to the experimenter.

To assess a relationship between impaired or impoverished declarative memory representation and gesture, we also coded each narrative for episodic and semantic content following the Autobiographical Interview (AI) scoring procedures outlined by Levine et al., (2002). This procedure has been used extensively in the literature to analyze episodic/autobiographical narratives (Irish, Addis, Hodges, & Piguet, 2012; Race et al., 2011) and more recently extended to the analysis of picture descriptions narratives (Race et al., 2011; Zeman, Beschin, Dewar, & Della, 2012). This study is the first to our knowledge to apply AI scoring to procedural narratives, and we applied the same AI scoring guidelines typically used with episodic/autobiographical narratives. Following established conventions, details were defined as unique occurrences, observations or thoughts, which each independently convey information, and each detail was classified as either internal or external. Internal details pertained directly to the prompted task/main event described and contained elements of episodic reconstruction and re-experiencing (e.g., reference to event, time, place, perceptual and emotional/though information). External details were those considered to be extraneous to the main event as well as semantic and other details and repetitions. The main variable of interest was the proportion of internal-to-total details per narrative, a measure of episodic re-experiencing.

2.4 Analysis

For our analyses, we used mixed effect regression models that predicted the dimension of interest as a function of group (amnesic patient versus healthy comparison). This allowed us to examine if there were indeed differences in the gesture produced for amnesic versus comparison participants. We determined the random effect structure for each model by using log-likelihood ratio testing; this allowed us to find the maximal random effect structure justified by the data for each model. We used dummy coding in all of our models with patients with amnesia as the reference group for group.

3. Results

3.1. Word Count

All participants were highly variable in the amount of spoken language produced in the task. At the group level, amnesic participants and healthy comparison participants produced similar amounts of words across all topics, with amnesic participants producing on average 268.1 (SD = 226.2) words and comparison participants producing 281.3 words (SD = 179.95) per topic. Table 2 shows these broken down by discourse narrative topic.

Table 2.

Number of words produced and the number of gestures produced per one hundred words for each of the discourse narrative types by group.

| Shopping | Sandwich | FrightExp | JFK | All | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | ||

| Amn. | Words Gestures |

199.6 | (56.7) | 337.0 | (341.2) | 380.1 | (269.3) | 155.8 | (75.5) | 268.1 |

| 2.90 | (1.12) | 3.29 | (2.90) | 4.55 | (1.80) | 1.47 | (0.55) | 3.1 | ||

| Com. | Words Gestures |

275.8 | (110.7) | 166.0 | (65.5) | 443.8 | (197.2) | 239.4 | (196.3) | 281.3 |

| 3.02 | (1.97) | 5.70 | (2.77) | 7.81 | (3.04) | 5.20 | (3.50) | 5.4 | ||

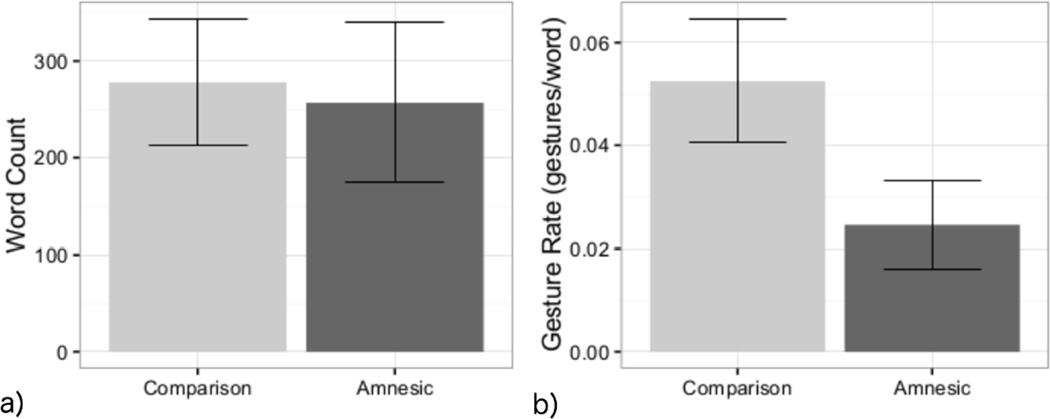

To assess whether there were differences in the total amount of speech produced as a function of group, we used a mixed effect model predicting word count, log-transformed for normality and standardized, with a fixed effect of group and random intercepts for participant pair and discourse topic. Group did not predict word count (β = 0.22, t(58.0) = 0.94, ns). Amnesic participants and comparisons participants produced similar amounts of words (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Word count by participant group across all discourse topics. The amount of speech produced was highly variable both within and across the different narratives. (b) Gesture rate by group across all discourse narratives. Participants with hippocampal amnesia gestured at a lower rate than healthy comparison participants. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, we examined if there were any differences in the amount of spoken language produced across topics. To do so, we reparameterized our model so that discourse topic was a fixed effect. We also included a fixed effect for group and their interaction and a random slope for topic on a random intercept for participant pair. The description of how to go shopping was the reference group for topic and the amnesia group was the reference group for participant group. Again, group did not predict log-transformed word count (β = 0.37, t(55) = 0.82, ns). Additionally, none of the topics significantly differed from the log-transformed word count in the shopping task (FE: β = 0.60, t(55)= 1.31, ns; Sa: β = −0.07, t(55)= −0.15, ns; JFK: β = −0.72, t(55)= −1.53, ns). Similarly, none of the interactions of group with topic were significant (FE×Group: β = −0.02, t(55)= −0.03, ns; Sa×Group: β = −0.80, t(55)= −1.24, ns; JFK × Group: β = 0.23, t(55)= 0.35, ns). The overall amount of spoken language was generally comparable across groups and across topics.

3.2. Gesture rate

All participants gestured in at least two of the four narrative tasks (i.e., some participants did not gesture for a given narrative). We first analyzed if there was a difference in the likelihood that gestures would be produced for a topic, regardless of rate. We analyzed this with a binomial mixed effect modeling predicting whether or not gesture was produced in a narrative as a function of group, with random intercepts for participant pair and topic. Comparison participants were significantly more likely to gesture during a topic than patients with amnesia (β = 2.46, z = 2.08, p < .05), with one comparison participant not gesturing for one topic and three patients with amnesia not gesturing across a total of 7 individual topics.

Gesture rate was determined by dividing the number of gestures produced in a narrative by the total number of words produced. For participants who did not gesture, gestures rates of 0 were included in this analysis. Across all narratives, amnesic patients gestured at a rate of 0.024 (2.4 gestures per 100 words; SD = 0.02) and healthy comparison gestured at rate of 0.053 (5.3 gestures per 100 words; SD = 0.03). See Table 2 for the mean gesture rate for each discourse narrative. Our preliminary model of gesture rate had the same structure as the model of word count. Group significantly predicted standardized gesture rate (β = 0.88, t(58) = 4.36, p < .001); amnesic patients had a significantly lower gesture rate than comparison participants did (Figure 2, panel b).

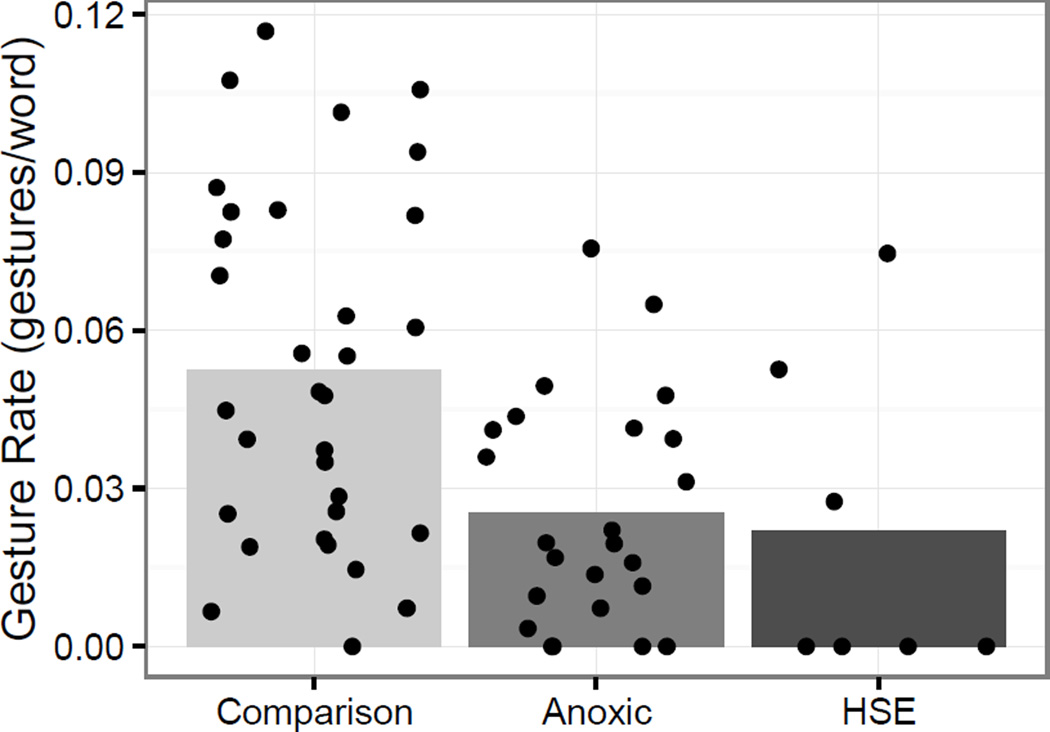

Given the differences in extent of brain damage between the anoxic and HSE patients, we examined gesture rate for these two patient groups separately. As can be seen in Figure 3, the pattern of gesture rate across narratives for the anoxic and HSE participants was similar both in distribution and in terms of the mean group gesture rates (anoxic M = 0.025 (sd = 0.02); HSE M= 0.22 (SD = 0.03)). Thus, it is not the case that the patients with HSE gesture significantly less, on average, than the anoxic patients or that HSE patients, with larger lesions, were driving the amnesia group findings.

Figure 3.

Gesture rate with the patient groups broken down by etiology. Each point represents a single participant’s gesture rate within a topic.

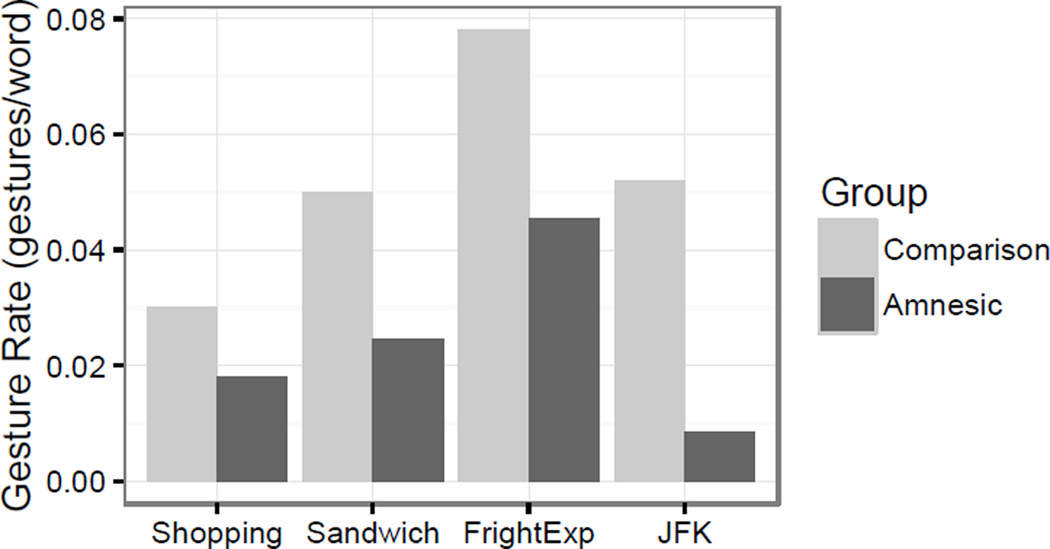

We next analyzed whether gesture rate varied as a function of discourse topic for participants with amnesia and comparison participants. We predicted standardized gesture rate as a function of group, topic, and their interaction. The explanation of grocery shopping topic was again used as the reference group. The random effect structure included a random slope for task on a random intercept for participant. Topic significantly predicted standardized gesture rate for the frightening experience description (β = 0.86, t(45)= 2.16, p < .05; Figure 4); participants gestured more when describing their most frightening experience than when describing how to go grocery shopping. None of the remaining main effects of topic were significant (JFK: β = − 0.26, t(22) = −0.60, ns; Sa: β = 0.20, t(45)= 0.52, ns). Group did not predict gesture rate (β = 0.37 = 0.01, t(45)= 0.97, ns). None of the interactions of group with task predicted gesture rate (FE: β = 0.65, t(45)= 1.17, ns; JFK: β = 0.95, t(47)= 1.68, ns; Sa: β = 0.41, t(45)= 0.75, ns). Thus, with the exception of gesturing more for frightening experiences, there appeared to be no systematic differences in gesture rate by task or participant group.

Figure 4.

Gesture rate by task. Participants tended to gesture more when describing their most frightening experience than when describing how to go shopping.

3.3. Gesture type

Finally, we examined the proportion of representational gestures produced by each participant for each narrative. Because so few deictic gestures were produced overall, we collapsed iconic and deictic gestures into one category - representational gestures – as their form depicts or demonstrates what was being conveyed through speech. Beat gestures were considered non-representational gestures. Representational gestures were frequently produced in all narratives, and we reasoned that if hippocampal integrity is required for the rich reconstruction of an event then perhaps patients with hippocampal amnesia might produce fewer representational gestures overall. We divided the total number of representational gestures in each narrative by the total number of gestures in each task for all participants. Comparison participants produced representational gestures 68.9% of the time compared to the amnesic participants 70.1%. Using a mixed effect model predicting the proportion of representational gestures in each task, standardized, with a fixed effect of group and random effects of task and participant, we found no difference in the proportion of representational gestures (β =−0.05, t(49)= −0.17, ns). Thus, despite the fact that patients gestured less overall, they still produced the same relative amount of representational gestures as comparison participants.

We then reparameterized our model to assess if there were differences in the proportion of representational to non-representational gestures in each of the discourse topics. In addition to a fixed effect of group, we added a fixed effect of discourse topic and its interaction with group into the model, along with a random slope for task on the random intercept or participant pair. None of the interactions of group and topic significantly predicted standardized proportion of representational gestures (Sa: β = −0.83, t(34)= −1.11, ns, FE: β = 0.03, t(32)= 0.38, ns; JFK: β = −0.16, t(32)= −0.21, ns). Group again did not predict representational gesture use (β = 0.18, t(34) = 0.33, ns) nor did task (Sa: β = 0.86, t(18)= 1.30, ns, FE: β = 0.20, t(18)= 0.34, ns; JFK: β = 0.54, t(28)= 0.82, ns). Therefore, participants did not alter their representational gesture production based on their memory impairment or discourse topic.

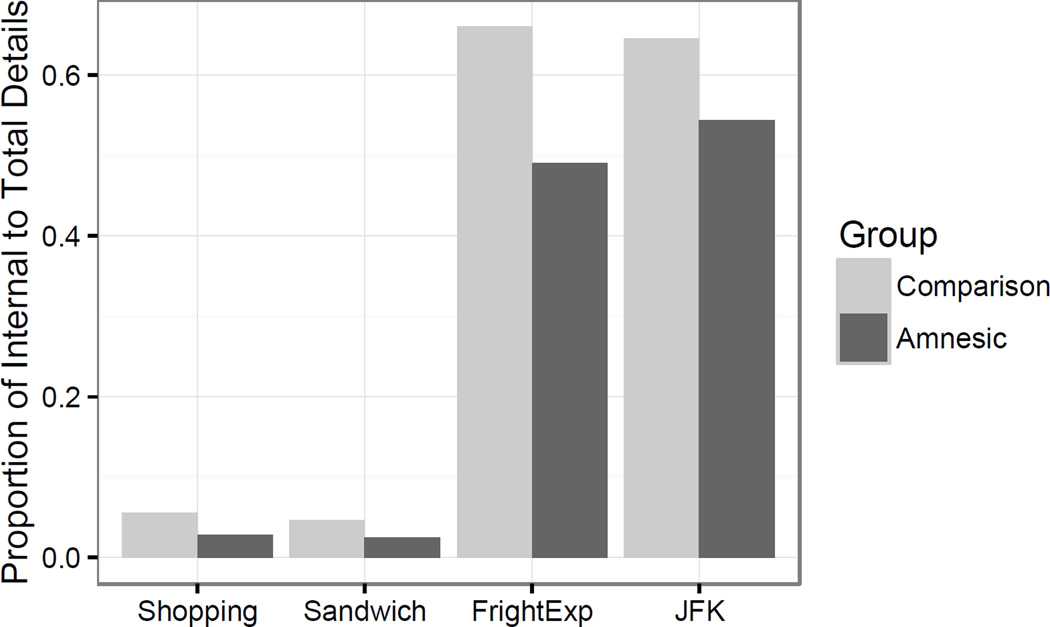

3.4. Episodicness of Narratives

The number of internal and external features varied systematically by topic. Unsurprisingly given task demands, the autobiographical narrative topics (JFK and frightening experience) tended to have higher numbers of internal features (i.e., more episodic) than the procedural narratives (sandwich making and shopping descriptions; Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean number of internal and external features (and standard deviations) in each of the discourse topics by group.

| Topic | Group | Int. Features | Ext. Features | Total Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FrightExp | Comparison | 25.38 (14.17) | 12.12 (9.67) | 37.50 (16.02) |

| Amnesic | 13.88 (9.75) | 15.00 (11.13) | 28.88 (14.32) | |

| JFK | Comparison | 10.88 (4.97) | 6.50 (3.96) | 17.38 (5.48) |

| Amnesic | 6.71 (3.04) | 5.29 (1.79) | 12.00 (3.87) | |

| Sandwich | Comparison | 1.00 (1.77 | 16.00 (5.29) | 17.00 (6.30) |

| Amnesic | 0.25 (0.71) | 12.25 (5.78) | 12.50 (5.61) | |

| Shopping | Comparison | 1.13 (1.64) | 18.75 (2.92) | 19.88 (2.64) |

| Amnesic | 0.63 (1.77) | 17.50 (6.37) | 18.13 (6.55) |

For each narrative, we calculated the proportion of internal-to-total details. To determine group differences in the amount of episodic details in the narratives we analyzed the proportion of internal-to total details in a mixed effect model predicting the standardized percentage with fixed effects of group, topic, and their interaction with a random slope for task on the intercept for participant pair. The frightening experience topic significantly predicted internal feature percentage (β = 1.47, t(55)= 6.17, p<.001; Figure 5); participants produced a higher percentage of episodic features when describing their most frightening experience than when describing how to go shopping. This same effect was also seen in the JFK description (β = 1.64, t(55)= 6.66, p <.001). There was no significant difference in percentage of internal features for the sandwich topic compared to the shopping topic (β =−0.01, t(55)= −0.05, ns). Group did not predict proportion of internal features; comparison participants and amnesic patients produced similar amounts of internal features (β = 0.09, t(55)= 0.37, ns). None of the interactions of group and topic significantly predicted the percentage of internal features (FE: β= 0.46, t(55)= 1.35, ns; JFK: β = 0.24, t(55)= 0.69, ns; Sa; β = −0.02, t(55)= −0.06, ns). Thus, there were clear differences in the episodic features provided by topic, with the autobiographical narrative tasks (JFK and frightening experience) containing more internal, episodic features than the shopping topic. The sandwich-making topic did not appear to differ from the shopping task in the percentage of internal features.

Figure 5.

The proportion of internal to total details in each of the tasks. There were significantly higher proportions of episodic features in the frightening experience and JFK descriptions relative to the shopping description. Comparison participants provided descriptions with a higher proportion of episodic features than patients with amnesia.

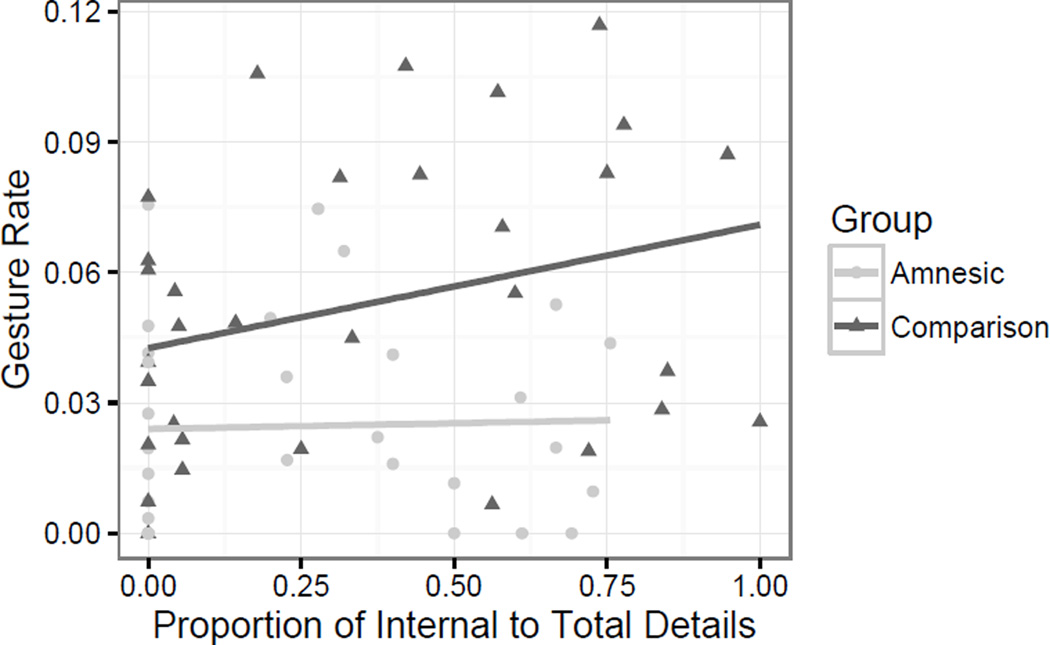

We next analyzed the relation between the percentage of internal features in each story and the gesture rate. If there is a relationship between hippocampal declarative memory and gesture production, then we might expect that narratives with more episodic details yield a higher rate of gesture production. We analyzed this with a mixed effect model predicting standardized gesture rate with fixed effects of the standardized ratio of internal features, group, and their interaction. There were random intercepts for task and participant pair. For patients with amnesia, the percentage of internal features was indeed negatively related to gesture rate, although this trend did not reach significance (β =−0.26, t(31)= −1.08, p = 0.29). Group predicted percentage of internal features: comparison participants tended to produce more internal features than patients with amnesia across all tasks (β = 0.91, t(58)= 4.40, p < .001). Interestingly, the interaction of group and percentage of internal features was also significant (β = 0.52, t(57)= 2.07, p < .05); for comparison participants, percentage of internal features was a positive predictor of gesture rate. Relative to patients with amnesia, comparison participant gestured at higher rate when they described stories with more episodic features.

Finally, to assess whether the effect of proportion of internal features on gesture rate was different for the two types of discourse tasks (procedural discourse versus autobiographical/episodic), we used two models – one for each type of task – that predicted standardized gesture rate as a function of the standardized ratio of internal features, group, and their interaction. For the two episodic tasks, group was a marginal predictor of gesture rate (β = − 0.85, t(23) = −1.85, p < .08); patients with amnesia tended to gesture at a lower rate than healthy comparison participants. The standardized internal ratio did not predict gesture rate (β =−0.32, t(21) = −1.18, ns), nor did its interaction with group (β =−0.65, t(24) = −1.39, ns). For the two procedural tasks, group did not significantly predict gesture rate (β =−0.64, t(27) = −0.58, ns). Neither did the standardized internal ratio (β = 0.69, t(27) = 0.81, ns), nor their interaction (β = − 0.12, t(27) = −0.10, ns). Therefore, the proportion of internal features did not predict gesture rate or interact with group to predict gesture rate in either set of tasks alone. Importantly, however, these tasks have restricted ranges. Because the combined analysis assessed a broader range of variation in the proportion of internal features and found a reliable interaction with group, even with a random task effect, it seems unlikely that these findings are the result of task differences alone.

4. Discussion

Although it seems intuitive that gestures emerge from representations in memory for what is being communicated (De Ruiter, 1998; Wesp et al., 2001), a link between representations in memory and gesture production has not been previously identified. The current study investigated the hypothesis that gesture is, in part, supported by hippocampal memory representations. The motivation for hypothesizing a relationship between the hippocampal declarative memory system and gesture stems from work pointing to the role of the hippocampus in relational binding and in representational flexibility for the reconstruction and recreation of richly detailed, multimodal, mental representations of experience (e.g., Eichenbaum & Cohen, 2001), and the disruptions in such representations following hippocampal amnesia (e.g., Hassabis et al., 2007; Kurczek et al., 2015; Race et al., 2011). The critical question addressed here was: do these disruptions extend to the production of gesture? The answer is yes. Patients with hippocampal amnesia produced significantly fewer gestures than healthy comparison participants, suggesting that the rich, multifaceted representations supported by the hippocampus contribute to gesture production.

Further evidence in support of a link between hippocampal declarative memory and gesture production came from our analysis of the episodic features present in the narrative as a predictor of gesture rate. In healthy comparison participants, we found an association between the proportion of episodic detail in the narratives and higher rates of gesture. In contrast, patients with amnesia did not show this same relationship. These data lend support for the idea that hippocampal dependent declarative memory, at least in part, provides support for gesture production.

We should note that recent work has blurred some of the lines between historical definitions of declarative and non-declarative memory that emphasize dissociations between memory systems (e.g., conscious memory processing has long been associated with hippocampal declarative memory). Growing evidence points to hippocampal involvement in unconscious memory processing if the memory demands are relational in nature (see Hannula & Greene, 2012 for a review). Although we cannot rule the contribution of non-declarative or procedural memory processes to some aspects of gesture production, these data do provide strong evidence for the role of hippocampal integrity in gesture production and establish an initial link between hippocampal declarative memory processes and gesture. An open question that warrants further investigation is if the nature of the relationship between gesture and memory is stable across tasks and behaviors, or if there are conditions or contexts in which gesture might engage non-declarative or procedural memory (see Klooster, Cook, Uc, & Duff, 2015). Future research should characterize co-speech gesture across a wider range of communicative tasks in comparisons participants, as well as patients with amnesia, in order to better understand the possible interactions between communicative demands, forms of memory representation, and communicative behavior.

Although these data are the first to demonstrate a link between gesture and hippocampal declarative memory, they fit with a growing body of work pointing to the breadth of cognitive and behavioral performances that receive hippocampal contributions. Hippocampal declarative memory has been shown to contribute to a range of abilities including, but not limited to decision making (e.g., Zeithamova, Schlichting, & Preston, 2012), creativity (e.g., Duff, Kurczek, Rubin, Cohen, & Tranel, 2013), social cognition (Spreng & Mar, 2012), and language processing (e.g., Duff & Brown-Schmidt, 2012). Indeed, there is increased recognition of hippocampal contributions to flexible cognition and behavior (see Rubin, Watson, Duff, & Cohen, 2014, for a review). How gesture is integrated with other behaviors and cognitive domains, and flexibly deployed across communicative contexts promises to offer new insights into the study of hippocampal contributions to flexible behavior more broadly.

There are, of course, alternative interpretations that warrant further consideration and subsequent investigation. One possible interpretation of reduced gesture production in amnesia relates to working memory or cognitive load; because patients with hippocampal amnesia exhibit deficits in relational (and episodic) memory processing (even over very short delays) perhaps their difficulties accessing, constructing, and maintaining these mental representations results in fewer gestures relative to healthy comparison participants. Although our data cannot speak directly to this possibility, such an interpretation seems to run counter to existing data in the literature. That is, instead of an inverse relationship between gesture and working memory demands, gesture appears to relieve demands on working memory (Cook, Yip, & Goldin-Meadow, 2016) and rates of gesture increase when conceptual demands are high (Hostetter, Alibali, & Kita, 2007; Kita & Davies, 2009). Based on these findings we might expect higher rates of gesture in the memory impaired patients completing tasks shown to place high demands memory rather than the reduced rates of gesture we observed. Future studies that manipulate working memory demands to fully understand the relationship between gesture and different forms of memory in patients are warranted.

Another interpretation of our findings is that the deficit we observe here is not linked to a general deficit in hippocampal declarative memory but to more specific contributions of hippocampus to spatial representation, and contributions of spatial representations to gesture production. Space is one of many relations known to be supported by the hippocampus (Konkel & Cohen, 2009) with some researchers arguing for a privileged role of spatial processing by the hippocampus (e.g., O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978). Given that gesture is spatial in nature and well-suited to communicate spatial and action information (Hostetter & Alibali, 2008), speculation about a special connection between hippocampal supported spatial processing and the spatial affordances of gesture seems natural. However, we do not have specific data or conditions built into the current study to directly assess this possibility but future studies could be designed to do so.

Lastly, there are also likely more general communicative and pragmatic factors at work affect gesture production. One such factor is the common ground – the mutually shared knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions (Clark & Marshall, 1978) – between conversation partners that guides language production. Common ground has been shown to affect gesture in multiple ways, with higher levels of common ground leading to both higher and lower rates of gesture production (Gerwing & Bavelas, 2004; Hilliard, O’Neal, Plumert, & Cook, 2015; Holler & Wilkin, 2009) and gestures that are lower in space (Hilliard & Cook, 2015b) than when common ground is lacking. In the data presented here, we might expect that healthy comparison participants would gesture more for the episodic tasks, since their listener, the experimenter, lacks knowledge about their specific autobiographical experiences but does have more generalized knowledge about information in the procedural tasks (shopping, making a sandwich). Indeed, we did observe a lower rate of gesture across all participants in the procedural compared to the autobiographical tasks. However, the patients gestured less across all tasks including the procedural tasks. Is it possible that the patients lack awareness of what their listener does and does not know and therefore do not adjust their gesture rate in the same way as health participants, who use such knowledge to tailor their communication in both speech and gesture? Our group has investigated common ground representations in many of these same patients and find that amnesic patients can represent some aspects of shared knowledge, but not others. For example, patients demonstrate the ability to acquired shared labels for with a communication partner and use those labels consistently across multiple interactions (Duff, Hengst, Tranel, & Cohen, 2006) but they fail to use definite reference in speech to signal that this information is shared; healthy participants quickly move from using an indefinite article, a (e.g., a camel) when describing the objects, to the definite article, the (e.g., the camel) while amnesic patients continue to use the indefinite articles more often (Duff, Gupta, Hengst, Tranel, & Cohen, 2011). Taken together, this work suggests that such successes and failures in representing and using common ground information may depend on the extent to which such behaviors depend on hippocampal declarative memory. Future work should more directly address the relations between gesture and common ground representation in in this population by analyzing other properties of gesture beyond just gesture rate (e.g., gesture height, size, speed, etc.; see Hilliard & Cook, 2015a).

With respect to the gesture literature, the results here argue against a pure action-based account of gesture production. For example, the Gesture as Simulated Action (GSA) framework argues that speakers simulate actions and perceptual states, that then activate motor and premotor cortices, leading to gesture production (Hostetter & Alibali, 2008). According to the GSA framework, the more a representation in the mind is grounded in action, the more likely it is that a gesture is produced. There is a long history and large literature revealing that learning of and memory for motor skill and action, or procedural memory, is intact in patients with hippocampal amnesia (e.g., Cavaco et al., 2004; Cohen & Squire, 1980; Milner, 1962). If action representations are intact in patients with hippocampal amnesia, and gesture emerges from these action representations, then gesture should have been relatively unimpaired in patients. The reduced gesturing by patients with hippocampal amnesia suggests that action representations alone may not be sufficient to trigger a gesture or explain why and under which circumstances people gesture.

Our gestures iconically represent our thoughts and thus reflect our representations in memory. By examining the gesture production of patients with hippocampal amnesia, we uncovered a potential mechanism for gesture production: hippocampal declarative memory representations. These representations are impoverished in patients with hippocampal amnesia, and these patients have a diminished gesture rate, without a concomitant reduction in speech rate. This finding is the first to empirically link gesture production with hippocampal integrity and the declarative memory system. By examining the cognitive and neural mechanisms that support gesture, memory, and their relationship, we can uncover how memory supports language and determine how gesture can be leveraged to facilitate learning and memory.

Figure 6.

The proportion of internal details and gesture rate by group. Comparison participants produced more internal details overall and increased their gesture rate with increasing proportions of internal details.

Table 3.

Mean number of gestures of each type (and standard deviations) produced in each task.

| Iconic | Deictic | Beat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FrightExp | Comparison | 11.00(14.17) | 0.13 (0.50) | 5.94 (8.88) |

| Amnesic | 4.69 (7.41) | 0.13 (0.34) | 3.25 (5.60) | |

| JFK | Comparison | 4.75 (9.88) | 0.625 (0.25) | 2.89 (7.26) |

| Amnesic | 0.31 (0.70) | 0.625 (0.25) | 0.25 (0.68) | |

| Sandwich | Comparison | 2.69 (3.96) | 0.38 (0.34) | 1.81 (3.92) |

| Amnesic | 3.12 (7.88) | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.69 (4.27) | |

| Shopping | Comparison | 2.69 (5.15) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.63 (3.19) |

| Amnesic | 1.13 (2.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.63 (1.26) |

Acknowledgments

Supported by CH (Delta Center Interdisciplinary Research Grant), SWC (NSF IIS-1217137, IES R305A130016), MCD (NIDCD R01-DC011755), and by an Obermann Center Interdisciplinary Research Grant to SWC and MCD. We thank Joel Bruss for making the anatomical figure.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alibali MW, Kita S, Young AJ. Gesture and the process of speech production: We think, therefore we gesture. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2000;15(6):593–613. http://doi.org/10.1080/016909600750040571. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JS, Tranel D, Bruss J, Damasio H. Correlations between regional brain volumes and memory performance in anoxia. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006;28(4):457–476. doi: 10.1080/13803390590949287. http://doi.org/10.1080/13803390590949287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell J, McNeill D, McCullough K-E. Speech-gesture mismatches: evidence for one underlying representation of linguistic and nonlinguistic information. Pragmatics & Cognition. 1998;6(2) [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco S, Anderson SW, Allen JS, Castro-Caldas A, Damasio H. The scope of preserved procedural memory in amnesia. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 8):1853–1867. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh208. http://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherney LR, Coelho CA, Shadden BB. Analyzing discourse in communicatively impaired adults. 1998 Aspen Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Clark H, Marshall C. Reference Diaries. Proceedings of the 1978 Workshop on Theoretical …. 1978:57–63. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=980272. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Squire LR. Preserved learning and retention of pattern-analyzing skill in amnesia: dissociation of knowing how and knowing that. Science. 1980 doi: 10.1126/science.7414331. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.7414331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SW, Yip TK, Goldin-Meadow S. Gesturing makes memories that last. Journal of Memory and Language. 2010;63(4):465–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2010.07.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SW, Yip TK, Goldin-Meadow S. Gestures, but not meaningless movements, lighten working memory load when explaining math. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2012;27(4):594–610. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2011.567074. http://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2011.567074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16(6):693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ruiter JP. Doctoral Dissertation, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. 1998. Gesture and speech production. [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Brown-Schmidt S. The hippocampus and the flexible use and processing of language. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012 Apr;6:69. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00069. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Gupta R, Hengst Ja, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. The use of definite references signals declarative memory: evidence from patients with hippocampal amnesia. Psychological Science. 2011;22(5):666–673. doi: 10.1177/0956797611404897. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611404897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Hengst Ja, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. Talking across time: Using reported speech as a communicative resource in amnesia. Aphasiology. 2007;21(6–8):702716. doi: 10.1080/02687030701192265. http://doi.org/10.1080/02687030701192265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Hengst JA, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. Hippocampal amnesia disrupts verbal play and the creative use of language in social interaction. Aphasiology. 2009;23(7–8):926–939. doi: 10.1080/02687030802533748. http://doi.org/10.1080/02687030802533748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Hengst J, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. Development of shared information in communication despite hippocampal amnesia. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9(1):140–146. doi: 10.1038/nn1601. http://doi.org/10.1038/nn1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff MC, Kurczek J, Rubin R, Cohen NJ, Tranel D. Hippocampal amnesia disrupts creative thinking. Hippocampus. 2013;23:1143–1149. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22208. http://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Cohen NJ. From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Feyereisen P. How could gesture facilitate lexical access? Advances in Speech-Language Pathology. 2006 Jun;8:128–133. http://doi.org/10.1080/14417040600667293. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrieli JD. Cognitive neuroscience of human memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:87–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.87. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerwing J, Bavelas J. Linguistic influences on gesture’s form. Gesture. 2004;4:187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie M, James AN, Federmeier KD, Watson DG. Verbal working memory predicts co-speech gesture : Evidence from individual differences. Cognition. 2014;132(2):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.03.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S. The role of gesture in communication and thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3(11):419–429. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01397-2. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10529797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Nusbaum H, Kelly SD, Wagner S. Explaining math: gesturing lightens the load. Psychological Science. 2001;12(6):516–522. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00395. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11760141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula DE, Greene AJ. The hippocampus reevaluated in unconscious learning and memory: at a tipping point? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012 Apr;6:1–20. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00080. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula DE, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. The Long and the Short of It: Relational Memory Impairments in Amnesia, Even at Short Lags. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(32):8352–8359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5222-05.2006. http://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5222-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D, Kumaran D, Vann SD, Maguire Ea. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:1726–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610561104. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610561104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst Ja, Duff MC. Clinicians as communication partners: Developing a Mediated Discourse Elicitation Protocol. Topics in Language Disorders. 2007;27(1):37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard C, Cook SW. A technique for continuous measurement of body movement from video. Behavior Research Methods. 2015a:1–12. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0685-x. http://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard C, Cook SW. Bridging Gaps in Common Ground: Speakers Design Their Gestures for Their Listeners. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2015b;42(1):91–103. doi: 10.1037/xlm0000154. http://doi.org/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard C, O’Neal E, Plumert J, Cook SW. Mothers modulate their gesture independently of their speech. Cognition. 2015;140:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.04.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler J, Wilkin K. Communicating common ground: How mutually shared knowledge influences speech and gesture in a narrative task. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2009;24(2):267–289. http://doi.org/10.1080/01690960802095545. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter AB. When do gestures communicate? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(2):297–315. doi: 10.1037/a0022128. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0022128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter AB, Alibali MW. Visible embodiment: Gestures as simulated action. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15(3):495–514. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.3.495. http://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.15.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter AB, Alibali MW, Kita S. I see it in my hands’ eye: Representational gestures reflect conceptual demands. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2007;22(3):313–336. http://doi.org/10.1080/01690960600632812. [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Addis DR, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Considering the role of semantic memory in episodic future thinking: evidence from semantic dementia. Brain. 2012;135:2178–2191. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws119. http://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita S, Davies TS. Competing conceptual representations trigger co-speech representational gestures. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2009;24(5):761–775. http://doi.org/10.1080/01690960802327971. [Google Scholar]

- Klooster NB, Cook SW, Uc EY, Duff MC. Gestures make memories, but what kind? Patients with impaired procedural memory display disruptions in gesture production and comprehension. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2015 Jan;8:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.01054. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.01054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klooster NB, Duff MC. Remote semantic memory is impoverished in hippocampal amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2015;79:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.10.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkel A, Cohen NJ. Relational memory and the hippocampus: Representations and methods. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2009 Sep;3:166–174. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.023.2009. http://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.01.023.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkel A, Warren DE, Duff MC, Tranel DN, Cohen NJ. Hippocampal amnesia impairs all manner of relational memory. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2008 Oct;2 doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.015.2008. http://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss R, Chen Y, Gottesman R. Lexical gestures and lexical access: a process model. In: McNeill D, editor. Language and gesture. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 261–283. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=DRBcMQuSrf8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA261&dq =Lexical+Gestures+and+Lexical+Access:+A+Process+Model&ots=jCzP7xpsir&sig=CGH wXEI4C6GSOvUifVWwMbcc_Qk. [Google Scholar]

- Kurczek J, Wechsler E, Ahuja S, Jensen U, Cohen NJ, Tranel D, Duff M. Differential contributions of hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to self-projection and self-referential processing. Neuropsychologia. 2015;73:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.05.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lausberg H, Sloetjes H. Coding gestural behavior with the NEUROGES–ELAN system. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(3):841–849. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.841. (3) http://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Svoboda E, Hay JF, Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Aging and Autobiographical Memory : Dissociating Episodic From Semantic Retrieval. 2002;17(4):677–689. http://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill D. Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal About Thought. University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Milner B. Les troubles de la memoire accompagnant des lesions hippocampiques bilaterales. Physiologie de L’hippocampe. 1962:257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nooijer JA, De Gog T, Van, Paas F, Zwaan RA. Effects of imitating gestures during encoding or during retrieval of novel verbs on children’s test performance. Acta Psycholgica. 2013;144(1):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.05.013. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe JA, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. London, Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Race E, Keane MM, Verfaellie M. Medial temporal lobe damage causes deficits in episodic memory and episodic future thinking not attributable to deficits in narrative construction. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(28):10262–10269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1145-11.2011. http://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1145-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RD, Watson PD, Duff MC, Cohen NJ. The role of the hippocampus in flexible cognition and social behavior. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014 Sep;8:742. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00742. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JD, Althoff RR, Whitlow S, Cohen NJ. Amnesia is a deficit in relational memory. Psychological Science : A Journal of the American Psychological Society / APS. 2000;11(6):454–461. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00288. http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Mar RA. I remember you: A role for memory in social cognition and the functional neuroanatomy of their interaction. Brain Research. 2012;1428:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.024. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR. Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychological Review. 1992;99(2):195–231. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.2.195. http://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.99.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesp R, Hesse J, Keutmann D, Wheaton K. Gestures maintain spatial imagery. The American Journal of Psychology. 2001;114(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeithamova D, Schlichting ML, Preston AR. The hippocampus and inferential reasoning: building memories to navigate future decisions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012 Mar;6:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00070. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman AZJ, Beschin N, Dewar M, Della S. Imagining the present: Amnesia may impair descriptions of the present as well as of the future and the past. Cortex. 2012;49(3):637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.03.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]