Abstract

Background

Evidence-based, single-session STI/HIV interventions to reduce sexual risk-taking are potentially effective options for implementation in resource-limited settings and may solve problems associated with poor participant retention.

Purpose

To estimate the efficacy of single-session, behavioral interventions in reducing unprotected sex or increasing condom use.

Methods

Data sources were searched through April 2013 producing 67 single-session interventions (52 unique reports; N = 20,039) that included outcomes on condom use and/or unprotected sex.

Results

Overall, participants in single-session interventions reduced sexual risk taking relative to control groups (d+ = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.27). Within-group effects of the interventions were larger than the between-groups effects when compared to controls.

Conclusions

Brief, targeted single-session sexual risk reduction interventions demonstrate a small but significant effect, and should be prioritized.

Keywords: behavior, single, STI/HIV, brief, prevention, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Developing effective sexual risk reduction interventions that create positive sexual behavior change not only requires careful tailoring of intervention materials, but also necessitates doing so with limited resources and within various environments and infrastructures (1). The success of behavioral interventions targeting sexual risk reduction has been documented (2). A recent meta-analysis of behavioral interventions conducted in various settings and multiple countries found intervention effects for increased condom use and reduced STI/HIV incidence (3). Similar results appeared in meta-analyses of multi-session risk reduction interventions conducted with adolescents(4), men and women in Latin American and Caribbean countries(5), and in Asia (6). Despite these successes, sexual risk reduction interventions are typically presented in multiple sessions, and as a result may create issues with participant retention over time. Given that retention rates have shown to be a strong moderator of intervention efficacy on condom use (7), solutions are needed to address issues with participant attendance. One potential solution to retention issues associated with multi-session interventions would be the adaption of intervention content to a single-session format.

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated the efficacy of brief interventions in creating behavior change improvements in areas such as smoking (8, 9) and alcohol use (10, 11), as well as improvements in STI outcomes (12). A recent meta-synthesis of health behavior meta-analyses found that those meta-analyses including brief interventions produced more significant behavioral changes than those that only sampled studies with long interventions (13). Additionally, that single-session HIV interventions are more cost-effective has been demonstrated in a clinic-based trial that reduced STI incidence among patients (14). Although a previous meta-analysis found single-session interventions focusing on biological outcomes to be effective in reducing STIs at follow-up, as well as increased condom use in a subsample of studies (12), it only contained studies in STI clinics and other healthcare settings that primarily measured biological outcomes.

The current meta-analysis includes studies in a wider range of settings and regardless of whether a biological outcome was present, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of the efficacy of single-session behavioral interventions to change condom use and unprotected sex behaviors. We also examined single-session interventions to determine the effectiveness of specific behavioral change components and intervention formats, the impact of methodological quality, and the effect of important sample (e.g. ethnicity, gender, age) and intervention (e.g., group vs. individual sessions, type of implementation) characteristics.

METHOD

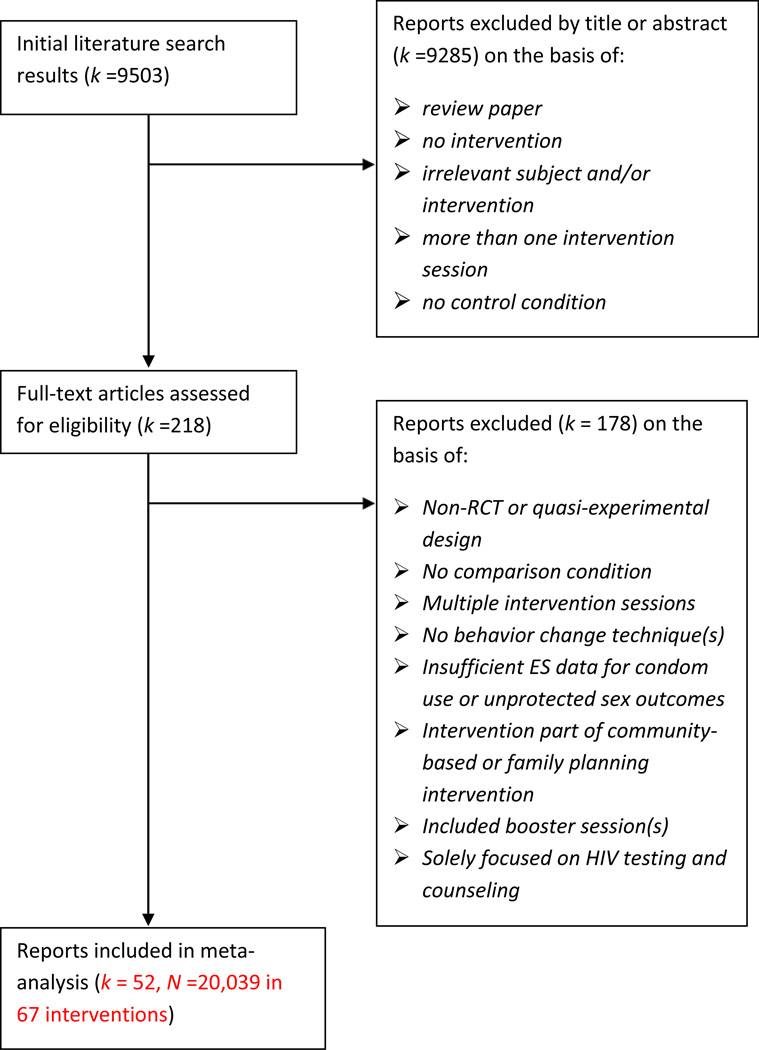

This meta-analysis was conducted to satisfy the standards implied by the PRISMA statement (15). We searched for qualifying studies using three strategies: a review of (a) electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, ProQuest, all international sub-databases in the WHO’s Global Health Library (LILACS, SEARO, EMRO, WPRO, WHOLIS, and AFRO), wherein we searched using a Boolean strategy for abbreviated and full keywords related to brief interventions using the following terms: intervention, behavior, AIDS, HIV, brief, single session, one session, education, program, counseling (search details are available upon request); (b) our own personal database and document archive of STI/HIV-related interventions and (c) reference sections of obtained articles. No language or date restrictions were applied. Studies available by April 2013 were eligible and included in the sample if they satisfied the following criteria: (a) a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or a quasi-experimental design with a comparison condition; (b) an intervention with only one session that included at least one behavior change technique; and (c) the publication reported or referenced a source with sufficient information to calculate effect sizes (ES) for either condom use or unprotected sex outcomes (i.e. outcomes labeled as “unprotected sex,” “never used condoms,” “sex without condoms”) for at least one follow-up assessment (See Figure 1 for further details). Eligible behavior change techniques included content targeting general STI/HIV education, attitudes toward condoms/partner reduction (communicating the positive consequences/benefits of performing targeted safe behaviors), assessing the pros and cons of risk behavior (e.g., decisional balance exercise), risk awareness/susceptibility to consequences (e.g., video of person with AIDS, scores on HIV knowledge test), condom skills training (e.g., practicing placing condom on model), communication skills training (e.g., condom negotiation, role playing), self-management skills training (e.g., emotion-focused coping, decision-making strategies), identification of high-risk situations (e.g., identify environmental prompts), and goal-setting/harm prevention plans. We excluded interventions if they included booster sessions, or if they only consisted of HIV testing and counseling without any additional content, as these programs have been reviewed and analyzed in other meta-analyses (16, 17, 18).

Figure 1.

Selection Process for Study Inclusion.

Intervention content was coded using descriptions in the included articles as well as manuals and session outlines. Two independent raters coded sample characteristics and risks (e.g., ethnicity, gender, age), experimental design and measurement techniques (e.g., length of session, methodological quality, behavioral outcomes), and format and content of interventions and controls following a coding manual that was previously developed and pilot tested. Methodological quality was determined by coding for previously validated items (19, 20) assessing random assignment of intervention and control groups, quality control (i.e. standardization of treatment), pretest evaluation, follow-up rate, follow-up length, confidentiality, use of objective measures (i.e. STIs), appropriate attrition analysis (e.g. intent-to-treat, imputing missing values), independent/double-blinding, and appropriate statistical analyses to assess intervention effects (overall scale range = 0–16). Disagreements between coders were resolved through discussion. Mean interrater reliability for categorical variables was calculated as Cohen’s (21) kappa = 0.85 and for continuous variables, calculated as the Spearman-Brown (22) correlation value, r = 0.95 (92% agreement). Standardized mean differences (d) were obtained as the effect size (ES) estimates for condom use and unprotected sex. The ES, d, was defined as the mean difference between treatment and control groups divided by the pooled standard deviation; if pretest data was reported for treatment and control groups, the effect size controlled for baseline differences (23). The effect size calculation controlled for baseline differences and small sample sizes (24, 25). In the absence of means and standard deviations, other statistical information (e.g., F-values) was used (26, 27). If a study reported dichotomous outcomes, we calculated an odds ratio and transformed it to d using the Cox transformation. Positive ds indicated intervention participants increased condom use or decreased unprotected sex compared to controls (28).

Trials varied in statistical measures of the behavioral outcome for safe sex (e.g., count, percent condom, mean and standard deviation of protected sexual events), and thus they were all transformed into the common ES index, d. We used the most distal time point available after the intervention (e.g., final follow-up) in order to capture the most conservative assessment of behavior change. When the study reported more than one follow-up, ESs were calculated for measures provided at the last follow-up after intervention completion. If an individual report evaluated more than one intervention condition, each condition was treated at as an independent study. Sensitivity analyses were performed in order to evaluate the influence of reports with more than one intervention.

Our primary outcome was overall sex risk, which was calculated by combining both unprotected sex and condom use outcomes if a study reported both instances, or either condom use or unprotected sex alone. We also separately analyzed unprotected sex outcomes and condom use outcomes. Positive ESs were indicative of intervention participants increasing condom use or decreasing unprotected sex compared to controls.

Asymmetries in distributions may indicate publication bias or other potential biases, and as a result we used three different strategies to examine possible bias: Trim and Fill, Begg’s strategy, and Egger’s test (29–31). All analyses were conducted in Stata 13.1 using macros for meta-analysis and using a “metafor” meta-analysis package for R (26, 32, 33, 34). Random-effects assumptions with restricted maximum likelihood variance estimation was used to obtain average condom use and unprotected sex effect sizes. Homogeneity (Q and I2) of the effect size was also examined (35).

We combined similar behavior change techniques to create three new composite behavior change content variables reflective of the Informational-Motivational-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model, which proposes three major contributors to HIV risk reduction: information, motivation, and behavioral skills (36). The composite variables include: (1) Information behavioral change techniques included general educational information and provision of HIV/STD-related materials. (2) Motivation behavioral change techniques included attitudes toward condom use and partner reduction, risk awareness feedback, assessing the pros and cons of risk behavior, and goal-setting and harm reduction plans. Goal-setting and harm reduction plans were categorized in the motivation category as they are indicators of behavioral intention and motivation to change risky behaviors. And (3) Skills behavioral change techniques included identification of high-risk situations, condom use skills, communication skills, and self-management skills. These techniques all represented concrete skills that were taught in the interventions and as a result were categorized as behavioral skills components. These moderator variables were entered into a series of weighted least squares regression models incorporating random-effects assumptions (33), and used the moving constant technique to produce estimates at meaningful levels of the moderators (37). The regression models were weighted least square regressions weighted by the inverse of the variable. The inclusion or exclusion of each behavior change technique was dummy coded and included in the regression as categories of 1 or 0 (included vs not included). The models were testing what intervention and/or sample, and/or study characteristics could be explaining the variability of the effect sizes. The moderators were entered as independent variables in regular regression models; if they were significant at explaining variability in the direction of the effect they would also be examined by the sign of the beta coefficient. If the variable was dummy coded and the beta coefficient was positive, that would indicate that the studies coded under the category 1 in that variable obtained larger effect sizes than those coded as 0 for that variable.

Additional moderator variables entered in this analysis included the following: publication year, mean age, ethnicity (Black, White, Asian, Hispanic, Other), gender, proportion heterosexual, experimental and control duration (minutes), weeks between intervention and follow-up, number of follow-ups, geographic region and country, theoretical foundation, interventions designed to target certain populations (adolescents, STI clinics, college students, high-risk drug/alcohol users, sexually high-risk participants, ethnicity, female sex workers, gender, HIV-positive/HIV-negative, and other), unit of assignment to intervention and control groups, experimental and control delivery format, control group type, whether interventions included additional content (HIV or STD counseling and testing, substance use counseling, condom provisions), and methodological quality.

RESULTS

As Table 1 shows, the studies were published between 1989 and 2013 (M = 2002, SD = 6.8). The average percentage of items satisfied for methodological quality score was 72% (SD = 13). In total, 20,039 participants from 67 single-session interventions (k) reported in 52 unique publications (38–90) were included in the current review. Demographic characteristics of participants varied across interventions, with 21 targeting females, 17 targeting males, and 29 targeting males and females. Interventions focused on adolescents (k=11), adults (k=51), both demographics (k=2), or reported the mean age of participants without specifying a range (k=3). The average age of participants was 30 years old (SD = 8.54). Interventions varied in target population, examining individuals from STI/HIV clinics (k=20) and other healthcare settings (k=12), college students (k= 6), men who have sex with men (MSM) (k=7), criminal-justice involved clients (k=3), injection drug users seeking methadone maintenance or detoxification treatment (k= 2), high school students (k=2), female sex workers (k=2), student teachers from Zimbabwe (k=1), and other various populations (e.g., truck drivers, male circumcision patients in South Africa, see Table 1) of adult men (k=2), adult women (k=6), and both adult men and women (k=4). Majority of the interventions were conducted in the United States (k= 52), while others were conducted in South Africa (k= 4), Mexico (k= 2), Canada (k= 2), Zimbabwe (k= 1), Zambia (k= 1), Malawi (k= 1), India (k= 1), Australia (k= 1), Singapore (k= 1), and Russia (k= 1). On average, study samples consisted of 61% males, 39% Blacks, 27% Whites, 4% Asians, 9% Hispanics, and 22% unreported/other.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Trials in the Sample.

| Study Citation |

Participants & Follow-up (FUP) |

Main inclusion criteria and study setting |

Study conditions | Length of intervention (min) |

Behavioral outcomes |

Intervention (I) & control (C) components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdala, 2013 (72) |

|

Sexually high-risk STI patients in Russia |

I – individual C – individual |

I – 60 C – N/A |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL, PRT, SUB, CND C – ED, RSK, CONST, PRT, CND |

| Agha, 2004 (38) |

|

10th and 11th grade students in Zambia |

I – group C - group |

I – 105 C – N/A |

|

I – ED, RSK, CONST, COMST, PRT C – water purification |

| Alemagno, 2009 (39) |

|

Criminal-justice involved clients in Ohio urban area |

I – computer delivered C – printed materials |

I – 20 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, MGTST, PRT C – PRT |

| Archibald, 1994 (79) |

|

Female sex workers in Singapore |

I – group C – WLC |

I – 180 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, CONST, PRT, TST, STI C – N/A |

| Belcher, 1998 (40) |

|

Sexually active women in a low- income inner city in Atlanta, GA |

I – group C – individual |

I – 120 C – 120 |

|

I – ED, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL, PRT, CND C – ED, RSK, PRT, CND |

| Bernstein, 2012 (73) |

|

Patients in an urban Level I Trauma Center ED |

I – individual C – SC |

I – N/A C – N/A |

|

I – ED, AT, PRO, GL, PRT, TST, STI, SUB, CND C – ED, PRT, TST, STI, SUB, CND |

| Boekeloo, 1999 (80) |

|

Adolescent patients in managed care in Washington, DC |

I – individual C – SC |

I – N/A C – N/A |

|

I – ED, RSK, PRT, CND C - CND |

| Bryan, 1996 (41) |

|

Unmarried female undergraduates from a large southwestern university |

I – group C – group |

I – 45 C – 45 |

|

I – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, CND C – stress management |

| Bryan, 2009 (42) |

|

Juvenile adolescents from Denver, CO |

I1 – group + video I2 – group + video C – group + video |

I1 – 180 I2 – 210 C – 60 |

|

I1 – ED, PRO, RSK, COMST, MGTST, GL I2 – ED, AT, PRO, RSK, COMST, MGTST, GL C – ED |

| Calsyn, 1992 (43) |

|

IDUs seeking treatment in Seattle, WA |

I – group + video C – WLC |

I – 90 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, TST, CND C – N/A |

| Chernoff, 2000 (44) |

|

College students from the University of Southern California |

I – individual C – printed materials |

I – 20 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, RSK, GL C – ED, PRT |

| Choi, 1996 (46) |

|

Asian or Pacific Islander homosexual men in San Francisco, CA |

I – group C – WLC |

I – 180 C – 0 |

|

I –ED, AT, PRO, CONST, COMST C- N/A |

| Cornman, 2007 (47) |

|

Long distance male truck drivers in Tamil Nadu, India |

I – group C – group |

I – 240 C - 240 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, CND C – ED, RSK, CND |

| Crosby, 2009 (81) |

|

Heterosexual African American men at an STI clinic |

I – individual C – SC |

I – 45–50 C – 5 |

|

I – ED, AT, CONST, COMST, CND C – ED, CND |

| Delamater, 2000 (48) |

|

African-American adolescent males at STI clinic |

I1 – video I2 – individual C – SC |

I1 – 14 I2 – 14 C – N/A |

|

I1 – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST, CND I2 – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST, CND C – CND |

| Diallo, 2010 (49) |

|

African-American women in Atlanta, GA |

I – group C – group |

I – 210 C – 150 |

|

I – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST, PRT, CND C – ED, AT, RSK, PRT, CND |

| Eaton, 2011 (50) |

|

At-risk, HIV- negative MSM in Atlanta, GA |

I – individual C – SC |

I – 40 C – 40 |

|

I – ED, AT, PRO, RSK, ID, C – ED, RSK |

| Edwards, 2000 (51) |

|

First-year college students in eastern Ontario, Canada |

I – group + video C – WLC |

I – 45 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, CONST, COMST C- N/A |

| Gibson, 1999 (Study 1) (52) |

|

IDUs entering heroin detoxification treatment at San Francisco General Hospital |

I – individual C – printed materials |

I – 50 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, PRO, CONST, TST C – PRT, TST |

| Gieck, 2007 (53) |

|

Heterosexual, sexually active males from University of Wyoming |

I – group C – group |

I – 90 C – 65 |

|

I – ED, AT, PRO, GL C – ED, RSK |

| Gilbert, 2008 (54) |

|

HIV-positive patients at outpatient HIV clinics in San Francisco Bay Area |

I – video C – SC |

I – 24 C – N/A |

|

I – ED, RSK, PRT, TST C – TST |

| Gollub, 2000 (82, 92) |

|

Women at an STI clinic in Philadelphia, PA |

I – group + video C – group + video |

I – 15–30 C – 15–30 |

|

I – ED, AT, CONST, COMST, PRT, TST, STI, CND C – ED, AT, CONST, COMST, PRT, TST, STI, CND |

| Grimley, 2009 (83) |

|

Lower-income men and women at an urban STI clinic in Birmingham, AL |

I – computer delivered C – computer delivered |

I – 15 C – 15 |

|

I – ED C – multiple health risk assessment |

| Hirshfield, 2012 (74) |

|

Sexually high-risk MSM across the United States |

I1 – video I2 – webpage C – no treatment control |

I1 – 9 I2 – N/A C – 0 |

|

I1 – ED, AT, RSK, COMST I2 – ED C – N/A |

| Jaworski, 2001 (55) |

|

Heterosexual, sexually active female college students |

I1 – group I2 – group C – WLC |

I1 – 150 I2 – 150 C – 0 |

|

I1 – ED I2 – ED, AT, PRO, RSK, COMST, MGTST, GL C – N/A |

| Jemmott, 1992 (56) |

|

Black, male adolescents from Philadelphia, PA |

I – group + video C – group + video |

I – 300 C – 300 |

|

I – ED, CONST, COMST C – career planning intervention |

| Jemmott, 2005 (84) |

|

African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic in Philadelphia, PA |

I1 – group + video I2 – group + video C – group + video |

I1 – 250 I2 – 250 C – 250 |

|

I1 – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST I2 – ED, AT, RSK C – health promotion |

| Jemmott, 2007 (85) |

|

Sexually experienced African American women at a health clinic in a hospital in Newark, NJ |

I1 – group + video I2 – group + video I3 – individual + video I4 – individual C – group |

I1 – 200 I2 – 200 I3 – 20 I4 – 20 C – 200 |

|

I1 – ED, AT, CONST, COMST I2 – ED, RSK I3 – ED, CONST, COMST, PRT I4 – ED, RSK, PRT C – health promotion |

| Kalichman, 2005 (86) |

|

Patients at an STI clinic in Milwaukee, WI |

I1 – individual + video I2 – individual + video I3 – individual + video C – individual + video |

I1 – 90 I2 – 90 I3 – 90 C – 90 |

|

I1 – ED, CONST, COMST, ID I2 – ED, AT, PRO, RSK, GL I3 – ED, AT, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, ID, GL C – ED |

| Kalichman, Cherry, 1999 (57) |

|

African-American men from an urban STI clinic |

I1 – group + video I2 – group + video C – group + video |

I1 – 180 I2 – 180 C – 180 |

|

I1 – ED, RSK, CONST, MGTST, GL, CND I2 – ED, RSK, CONST, MGTST, GL, CND C – ED, CND |

| Kalichman, 2008 (58) |

|

Shebeen attenders in a suburb of Cape Town, South Africa |

I – group C – group |

I – 180 C – 60 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL C – ED, RSK |

| Kalichman, 2011 (75) |

|

STI clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa |

I – individual C – individual |

I – 60 C – 20 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL, TST, STI, SUB C – ED, RSK, PRT, TST, STI |

| Kalichman, Williams, 1999 (59) |

|

African-American women from a county STI clinic in Atlanta, Georgia |

I – group + video C – group + video |

I – 150 C – 150 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL C – ED |

| Kennedy, 2013 (76) |

|

Young adult African American males |

I – individual C – individual |

I – 53 C – 53 |

|

I – ED, AT, CONST, COMST, ID, CND C – ED, CND |

| Lovejoy, 2011 (77) |

|

Sexually high-risk, older HIV+ participants |

I – individual C – SC |

I – 48 C – N/A |

|

I – ED, AT, PRO, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL C – N/A |

| Maibach, 1993 (60) |

|

At-risk women from 3 California communities (San Jose, East Palo Alto, and San Francisco) |

I1 – individual + video I2 – video C – video |

I1 – 50 I2 – 50 C – 37 |

|

I1 – ED, COMST, MGTST I2 – ED, COMST, MGTST C – ED |

| Mansfield, 1993 (87) |

|

Adolescents at an STI clinic in an urban children’s hospital |

I – individual C – SC |

I – 20 C – 10 |

|

I – ED, RSK, PRT, CND C – ED, PRT, CND |

| Martinez- Donate, 2004 (Study 1) (61) |

|

High school students from Tijuana, Mexico |

I – group + video C – no treatment control |

I – 180 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, RSK, CONST, COMST, ID C – N/A |

| Orr, 1996 (88) |

|

STI-infected female adolescents at two family planning clinics and an STI clinic |

I – individual C - SC |

I – 10–20 C – 20–20 |

|

I – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST, PRT C – ED, PRT |

| Patterson, 2008 (62) |

|

Female sex workers from Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico |

I – individual C – individual |

I – 35 C – 35 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, COMST, MGTST, GL C – ED, RSK, MGTST, GL |

| Patterson, 2003 (63) |

|

Sexually active, HIV-positive in San Diego, CA |

I1 – individual I2 – individual C – individual |

I1 – 90 I2 – 90 C – 270 |

|

I1 – CONST, COMST, MGTST I2 – RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST C – diet and exercise education (HIV- related) |

| Pedlow, 2004 (89) |

|

Patients at an STI clinic in Syracuse, NY |

I – individual C – SC |

I – 90 C – 45 |

|

I – ED, AT, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL, PRT C – ED, PRT |

| Peltzer, 2012 (78) |

|

Male circumcision patients in South Africa |

I – group C – group |

I – 180 C – 60 |

|

I – ED, PRO, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL, SUB C – ED |

| Peterson, 1996 (64) |

|

African-American homosexual and bisexual men in San Francisco Bay area |

I – group C – WLC |

I – 180 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, COMST, GL C – N/A |

| Proude, 2004 (65) |

|

Young adult patients seeing family physicians |

I – individual C – SC |

I – N/A C – N/A |

|

I – ED, RSK, PRT, CND C – N/A |

| Richardson, 2003 (66) |

|

Sexually active, HIV-positive patients at HIV clinics in California |

I1 – individual I2 – individual C – individual |

I1 – 4 I2 – 4 C – 4 |

|

I1 – ED, AT, GL, PRT I2 – ED, RSK, GL, PRT C - HIV medication adherence |

| Simbayi, 2004 (67) |

|

Patients at an STI clinic Cape Town, South Africa |

I – individual C – individual |

I – 60 C – 20 |

|

I – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST, ID, GL C – ED, RSK |

| Stein, 1997 (68) |

|

High-risk African- American and Hispanic women |

I1 – group + video I2 – group + video C – no treatment control |

I1 – 60 I2 – 120 C – 0 |

|

I1 – ED, RSK, CND I2 – ED, PRO, RSK, CONST, MGTST, TST, CND C – N/A |

| Tudiver, 1992 (69) |

|

Gay and bisexual men from Toronto, Canada |

I – group C – WLC |

I – 180 C – 0 |

|

I – ED, AT, RSK, CONST, COMST C – N/A |

| Valdiserri, 1989 (70) |

|

Homosexual and bisexual men from Pittsburgh, PA |

I – group C– group |

I – 140 C – 75 |

|

I – ED, CONST, COMST, MGTST C – ED, CONST |

| Wilson, 1992 (71) |

|

Student teachers from Zimbabwe |

I – group C – group |

I – 90 C – 60 |

|

I – RSK, CONST, COMST, MGTST C – ED |

| Wynendaele, 1995 (90) |

|

Patients at an STI clinic in Malawi |

I – individual C - SC |

I – N/A C – 0 |

|

I – ED C – N/A |

WLC-Wait-List Control SC-Standard Care ED-HIV/STI Education AT-Condom/partner reduction attitudes PRO-Pros and cons of risk behavior RSK-Risk awareness/feedback and/or susceptibility to consequences CONST-Condom skills training COMST-Communication skills training MGTST-Self-management skills training ID-Identification of high-risk situations GL-Goal-setting/harm prevention plans PRT-Provided general HIV/STI-related materials TST-HIV counseling/testing STI-Other STI counseling/testing SUB-Substance use counseling/treatment CND-Condoms provide graph export “C:\Users\Michael\Desktop\Graph.pdf”, as(pdf) replaced

Studies reported at least one follow-up (M = 2.08, SD = 0.82, range = 1 to 5), and the final follow-up session, on average, occurred about 32 weeks post-intervention (M = 31.68, SD = 18.56, range = 4 to 96 weeks). All trials analyzed condom use and/or unprotected sex outcomes. Some interventions exclusively reported condom use outcomes (k=25) or unprotected sex outcomes (k=20), and both categories of outcomes were reported for 22 interventions. Suggesting no publication bias, Begg’s and Egger’s tests revealed no asymmetries in effect sizes (Begg’s Test, zoverall sex risk= 0.69, p = 0.492, zcondom use = 0.29, p = 0.769, zunprotected sex = 0.14, p = 0.888; Egger’s test, toverall sex risk = 0.30, p = 0.65, tcondom use = −0.48, p = 0.558, tunprotected sex = 0.76, p = 0.414) and the trim-and-fill technique identified no added or excluded studies that were necessary to normalize the distribution either for condom use or unprotected sex.

Summary of Intervention Characteristics

The studies assessed differed substantially in their design, session duration, and in the components they incorporated (Table 1). Study trials varied in the number of different single session interventions provided, with forty reporting a two-armed design, ten reporting a three-armed design, and two reporting either a four-armed or five-armed design. Interventions were treated as single studies, making for 67 interventions. Interventions were delivered in a variety of ways, including one-on-one counseling (k=22), face-to-face group settings (k=17), videos alone (k=4), computer-delivered (k=3), and individual or group formats that also included a video (k=21). Session length in the experimental, single-session interventions ranged from 4 minutes to 6 hours in duration, with an average of 100 minutes.

The interventions typically combined multiple intervention components, and a few components were found predominantly across most of the interventions. Out of the 67 single-session interventions, 96% (k=64) included a presentation of general HIV/STI information, 37% (k=25) addressed attitudes towards condoms/partner reduction, 34% (k=23) assessed the pros and cons of risk behavior, 64% (k=43) communicated risk awareness/susceptibility to consequences, 55% (k=37) used condom skills training, 63% (k=42) targeted communication skills training, 36% (k=24) trained in self-management skills, 22% (k=15) taught about identifying high-risk situations, and 34% (k=23) prompted goal-setting and harm prevention plans.

The type of control used across the studies varied considerably as well, with controls (k=52) reporting the combination of multiple components. In total, 50% (k=26) of controls provided general HIV/STI education and 19% (k=10) communicated risk awareness/susceptibility to consequences. Additionally, three controls targeted condom skills training, two discussed attitudes towards condom use/partner reduction, one taught self-management skills, one taught communication skills, and one promoted goal-setting and risk reduction plans. Other elements of the intervention and control conditions included provision of general HIV/STI-related materials such as pamphlets and brochures (18% in interventions, 23% in controls), HIV counseling and testing (9% and 12%, respectively), other STI counseling and testing (6% and 8%), substance use counseling and/or treatment (1% and 2%), and provision of condoms (22% and 25%). Interventions included a variety of composite behavioral change variables (see Table 3).

Table 3.

IMB moderators for overall sexual risk outcome.

| IMB moderators for overall sexual risk outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| k | d+ia | 95% CI for d+ | |

| Information alone | 4 | 0.37 | (0.10, 0.64) |

| Behavior skills alone | 1 | 1.49 | (0.87, 2.12) |

| Info + Motivational | 14 | 0.12 | (−0.03, 0.27) |

| Info + Behavior Skills | 8 | 0.06 | (−0.14, 0.26) |

| Motivational + Behavior Skills | 2 | 0.55 | (0.13, 0.98) |

| Info + Motivation + Behavior Skills | 38 | 0.18 | (0.09, 0.26) |

Q-ModelIMBvariable = 23.77, p<0.0001

Overall Intervention Effects on Condom Use and Unprotected Sex Outcomes

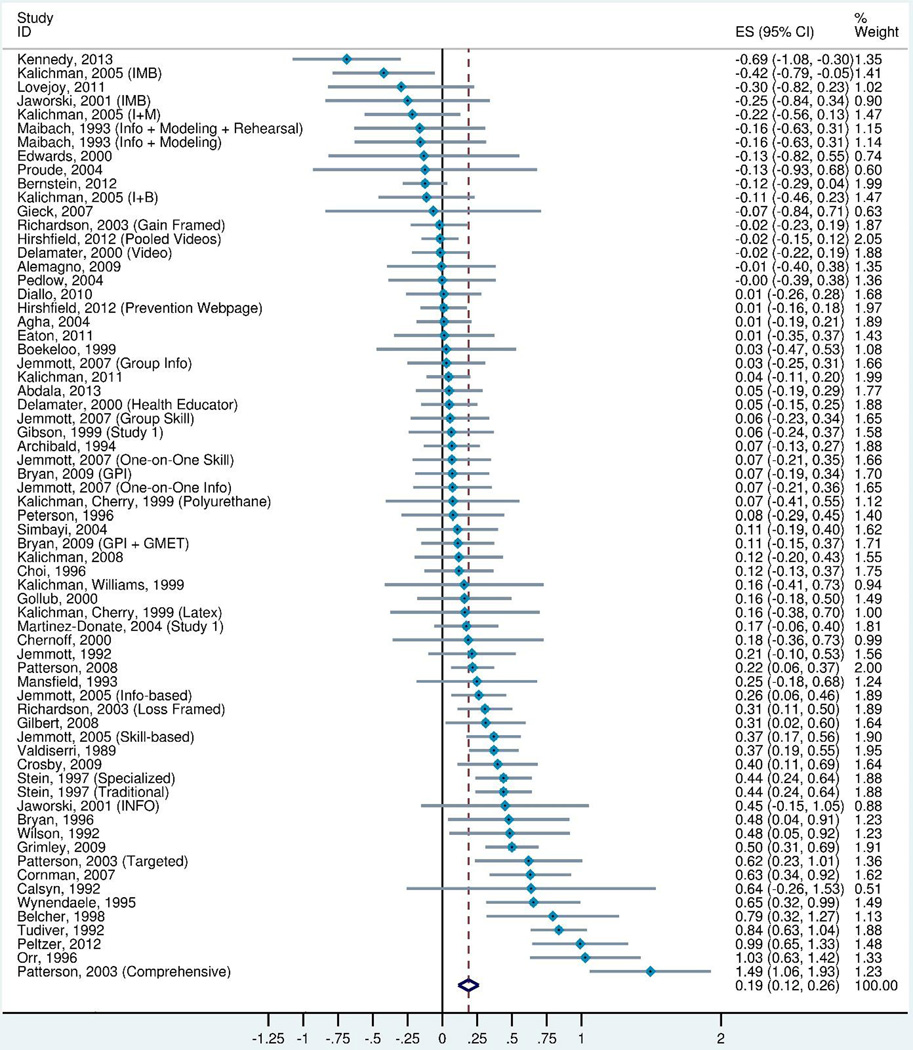

When compared to controls, single-session interventions were significantly more likely to decrease overall sexual risk (i.e. unprotected sex and condom use outcomes combined) (d+ = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.27) (k=67) (Figure 2 and Table 2). When analyzed separately, significant effects were also found for both condom use outcomes alone (d+ = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.04, 0.25) (k=47) as well as unprotected sex outcomes alone (d+ = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.29) (k=42) (see Table 2). However, significant heterogeneity was present, thus suggesting the presence of a moderator (I2overall sex risk = 77%, Q = 285.12, p-value = < 0.0001). Within group effects were analyzed for the overall sexual risk outcome to assess change over time in intervention and control conditions, and found that overall sexual risk significantly decreased from pretest to follow-up for single session interventions (d+ = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.18, 0.38) and control groups (d+ = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.02, 0.20) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of Overall Sex Risk effect sizes in order of magnitude.

Note: Weights are from random effects analysis. Effect sizes greater than zero indicate greater improvement in the intervention group compared to the control group, and effect sizes less than zero indicate greater improvement in the control group compared to the experimental group.

Table 2.

Weighted mean effect sizes at last follow-up.

| Outcome | k | Weighted mean d+ (95% CI) |

Homogeneity of effect sizes I2, Q (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sex Risk | 67 | 0.19 (0.12, 0.26) | 77%, 285.12 (<0.0001) |

| Change from baseline, treatment conditions |

48 | 0.28 (0.18, 0.38) | 93%, 642.32 (<0.0001) |

| Change from baseline, control conditions |

48 | 0.11 (0.02, 0.20) | 90%, 475.21 (<0.0001) |

| Condom Use Outcomes | 47 | 0.14 (0.05, 0.24) | 78%, 209.28 (<0.0001) |

| Unprotected Sex Outcomes | 42 | 0.20 (0.12, 0.29) | 78%, 185.40 (<0.0001) |

Note. Effect sizes are positive for differences that favor decreased risk (either compared to a control group or to the baseline, as noted).

Moderators for Overall Sexual Risk

Various combinations of Information, Motivation, and Skills components were significant moderators for overall sexual risk (see Table 3). Interventions were significantly more effective when they included Information alone (d+ = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.10, 0.64) (k=4), Skills alone (d+ = 1.49, 95% CI = 0.87, 2.12) (k=1), Motivation and Skills components (d+ = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.98) (k=2), and Information, Motivation, and Skills components combined (d+ = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.09, 0.26) (k=38). No other moderators were significant in the analysis. These moderator results are not conclusive due to the presence of small sample sizes and brief descriptions of intervention content in individual studies.

DISCUSSION

Our meta-analysis provides support for conducting single-session behavioral interventions in various environments with an assortment of targeted populations. Overall, these interventions had a small but significant effect in reducing sexual risk, as defined by condom use and unprotected sex. Despite the small effect, it is important to note that follow-up measurement points were conducted about thirty-two weeks following the completion of interventions, providing support that single session interventions can result in sustained long-term behavioral change. These findings present a unique contribution to the current literature that builds upon a previous meta-analysis that found single session interventions to be effective in reducing STI incidence and increasing condom use in STI clinics and other healthcare settings (12). The current meta-analysis provides additional support for single session interventions, as it includes a wider range of study settings, and did not require the report of a biological measure at follow-up.

Another interesting finding was that within-group effects of the interventions were larger than the between-groups effects when compared to controls. This result can partially be explained by the positive within-group effects of control groups. Upon further analysis, we found that between-groups effects were not different based on whether the control was a weaker condition (i.e. wait-list group) or stronger condition (i.e. contained content relevant to HIV risk reduction), thus explaining the larger within-group effects of interventions.

Moderator results for IMB variables should not be viewed as conclusive given small sample sizes for each category (or combination of categories) of the IMB model, as well as limited descriptions of interventions reported in individual publications.

Limitations

Although our meta-analysis establishes the success of single session interventions when compared to controls, as well as identifies important behavioral change technique moderators, we did not code intervention and control content for an in-depth, exhaustive list of activities or strategies. Several studies provided only brief summaries of intervention content, thus making it difficult to discern variance of intervention components between studies. Limited description of behavioral interventions makes it difficult to explain heterogeneity in results. A recent audit found that many journals do not provide specific instructions to authors regarding provision of intervention descriptions, and thus going forward should offer more specific directions (91). Given more detailed intervention descriptions, future meta-analyses could focus more specifically on behavior change techniques and their individual role in creating positive behavioral outcomes. Coupled with our finding on the efficacy of single session interventions in general, in addition to results on the success of some general behavior change components, the identification of more specific and detailed behavior change techniques can assist in creating the best possible intervention format.

We were also surprised to find that no other moderators, outside of the IMB variables, were significant in the moderator analysis. For instance, one would expect the time between intervention and follow-up measurement to be a significant moderator, as a natural decline of intervention effects over time would be anticipated. The lack of any other significant moderators may indicate a limitation in power to determine moderator effects in the current meta-analysis.

Conclusion

The recent and historical success of HIV/STI behavioral interventions in creating positive unprotected sex and condom use outcomes requires an additional step in action to reach low-resource, high-risk populations internationally. A primary solution may be the adaptation of proven intervention content to a single-session format, a decision that will ultimately save researchers resources as well as avoid problems with participant retention commonly seen in multiple-session interventions. By disseminating knowledge and skills in such a brief encounter, participants will avoid travel expenses and large time commitments, making them more likely to attend the intervention. As our meta-analysis has shown, single session interventions have the ability to increase condom use and decrease unprotected sex if the proper content and format is implemented. Future research should focus on the inclusion of more in-depth analysis of behavior change techniques, in order to isolate more detailed constructs responsible for successful behavior change. In order to test the effects of specific intervention components, the inclusion of complete intervention descriptions should be prioritized by research authors.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by NIH grant (R01-MH058563). We thank Michelle R. Warren for assistance with the search for studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent was not applicable to our study as it contained no studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Sagherian, University of Connecticut (study design, search, manuscript writing, content coding, and conducted data analysis)

Tania B. Huedo-Medina, University of Connecticut (study design, the search, data analysis, and manuscript writing)

Jennie A Pellowski, University of Connecticut (search and content coding)

Lisa A. Eaton, University of Connecticut (study design, search and manuscript writing)

Blair T. Johnson, University of Connecticut (study design, data analysis, manuscript writing, and procured funding).

References

- 1.Johnson BT, Redding CA, DiClemente RJ, et al. A network-individual-resource model for HIV prevention. AIDS and behavior. 2010;14(Suppl 2):204–221. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9803-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albarracin D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho MH. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: a comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychological bulletin. 2005;131(6):856–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott-Sheldon LA, Huedo-Medina TB, Warren MR, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Efficacy of behavioral interventions to increase condom use and reduce sexually transmitted infections: a meta-analysis, 1991 to 2010. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2011;58(5):489–498. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823554d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Huedo-Medina TB, Carey MP. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents: a meta-analysis of trials, 1985–2008. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2011;165(1):77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, Lacroix JM, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Efficacy of HIV prevention interventions in Latin American and Caribbean nations, 1995–2008: a meta-analysis. AIDS and behavior. 2010;14(6):1237–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan JY, Huedo-Medina TB, Warren MR, Carey MP, Johnson BT. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of HIV/AIDS prevention interventions in Asia, 1995–2009. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2012;75(4):676–687. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Smoak ND, Lacroix JM, Anderson JR, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions for African Americans to reduce sexual risk of HIV: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2009;51(4):492–501. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a28121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2010;78(6):868–884. doi: 10.1037/a0021498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, West R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107(6):1066–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(3):301–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Braithwaite RS, Turner BJ, Fiellin DA. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of nonphysician brief interventions for unhealthy alcohol use: implications for the patient-centered medical home. Am J Addict. 2011;20(4):343–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton LA, Huedo-Medina TB, Kalichman SC, et al. Meta-analysis of single-session behavioral interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: implications for bundling prevention packages. American journal of public health. 2012;102(11):e34–e44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP. Meta-synthesis of health behavior change meta-analyses. American journal of public health. 2010;100(11):2193–2198. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweat M, O’Donnell C, O’Donnell L. Cost-effectiveness of a brief video-based HIV intervention for African American and Latino sexually transmitted disease clinic clients. AIDS. 2001;15(6):781–787. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denison JA, O’Reilly KR, Schmid GP, Kennedy CE, Sweat MD. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis, 1990--2005. AIDS and behavior. 2008;12(3):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. American journal of public health. 1999;89(9):1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 2006;55(Rr-14):1–17. quiz CE11-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WRBJ, Simpson TL, et al. What works? A Methodological Analysis of the Alcohol Treatment Outcome Literature: Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternatives. 2nd. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JA. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research (rev. ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Chacon-Moscoso S. Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 2003;8(4):448–467. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1988;41(2):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedges LV. Distribution Theory for Glass’s Estimator of Effect size and Related Estimators. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1981;6(2):107–128. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.HLS-Meta: Effect Size Converter to Create an Evidence-based Database. Storrs, CT: 2013. [computer program] Version 0.9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Chacón-Moscoso S. Effect-Size Indices for Dichotomized Outcomes in Meta-Analysis. Psychological Methods. 2003;8(4):448–467. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardbord RM, Higgins JPR. Meta-regression in Stata. Stata Journal, StataCorp LP. 2008;8(4):493–519. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological bulletin. 1992;111(3):455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson BT, Huedo-Medina TB. Depicting estimates using the intercept in meta-regression models: The moving constant technique. Research Synthesis Methods. 2011;2(3):204–220. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agha S, Van Rossem R. Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(5):441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alemagno SA, Stephens RC, Stephens P, Shaffer-King P, White P. Brief motivational intervention to reduce HIV risk and to increase HIV testing among offenders under community supervision. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2009;15(3):210–221. doi: 10.1177/1078345809333398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belcher L, Kalichman S, Topping M, et al. A randomized trial of a brief HIV risk reduction counseling intervention for women. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1998;66(5):856–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryan AD, Aiken LS, West SG. Increasing condom use: Evaluation of a theory-based intervention to prevent sexually transmitted diseases in young women. Health Psychology. 1996;15(5):371–382. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryan AD, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. HIV risk reduction among detained adolescents: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1180–e1188. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calsyn DA, Saxon AJ, Freeman G, Whittaker S. Ineffectiveness of AIDS education and HIV antibody testing in reducing high-risk behaviors among injection drug users. American journal of public health. 1992;82(4):573–575. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.4.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chernoff RA, Davison GC. An Evaluation of A Brief HIV/AIDS Prevention Intervention for College Students Using Normative Feedback and Goal Setting. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(2):91–104. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.3.91.62902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chesniak-Phipps LM. Examining the factors that influence sexual activity and condom use among African American youth. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi K-H, Lew S, Vittinghoff E, Catania JA, Barrett DC, Coates TJ. The efficacy of brief group counseling in HIV risk reduction among homosexual Asian and Pacific Islander men. AIDS. 1996;10(1):81–87. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cornman DH, Schmiege SJ, Bryan A, Benziger TJ, Fisher JD. An information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model-based HIV prevention intervention for truck drivers in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(8):1572–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delamater J, Wagstaff DA, Havens KK. The Impact of a Culturally Appropriate STD/AIDS Education Intervention on Black Male Adolescents’ Sexual and Condom Use Behavior. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(4):454–470. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diallo DD, Moore TW, Ngalame PM, White LD, Herbst JH, Painter TM. Efficacy of a single-session HIV prevention intervention for Black women: A group randomized controlled trial. AIDS and behavior. 2010;14(3):518–529. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eaton LA, Cherry C, Cain D, Pope H. A novel approach to prevention for at-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men: Creating a teachable moment to promote informed sexual decision-making. American journal of public health. 2011;101(3):539–545. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwards SB. An Investigation of a Condom Skills Modeling Intervention for Adolescents: To Prevent the Spread of AIDS. Kingston, Ontario, Canada: School of Nursing, Queen’s University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibson DR, Lovelle-Drache J, Young M, Hudes ES, Sorensen JL. Effectiveness of brief counseling in reducing HIV risk behavior in injecting drug users: Final results of randomized trials of counseling with and without HIV testing. AIDS and behavior. 1999;3(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gieck DJ. Development of a brief motivational intervention that targets heterosexual men’s preventive sexual health behavior. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilbert P, Ciccarone D, Gansky SA, et al. Interactive “Video Doctor” Counseling Reduces Drug and Sexual Risk Behaviors among HIV-Positive Patients in Diverse Outpatient Settings. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaworski BC, Carey MP. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(6):417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV Risk-Associated Sexual Behaviors among Black Male Adolescents: Effects of an AIDS Prevention Intervention. American journal of public health. 1992;82(3):372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalichman SC, Cherry C. Male polyurethane condoms do not enhance brief HIV-STD risk reduction interventions for heterosexually active men: results from a randomized test of concept. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1999;10(8):548–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, et al. Randomized Trial of a Community-based Alcohol-related HIV Risk-reduction Intervention for Men and Women in Cape Town South Africa. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(3):270–279. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalichman SC, Williams E, Nachimson D. Brief behavioural skills building intervention for female controlled methods of STD-HIV prevention: outcomes of a randomized clinical field trial. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1999;10(3):174–181. doi: 10.1258/0956462991913844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maibach E, Flora JA. Symbolic Modeling and Cognitive Rehearsal: Using Video to Promote AIDS Prevention Self-Efficacy. Communication Research. 1993;20(4):517–545. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martinez-Donate AP, Hovell MF, Zellner J, Sipan CL, Blumberg EJ, Carrizosa C. Evaluation of Two School-Based HIV Prevention Interventions in the Border City of Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(3):267–278. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patterson TL, Mausbach B, Lozada R, et al. Efficacy of a Brief Behavioral Intervention to Promote Condom Use Among Female Sex Workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. American journal of public health. 2008;98(11):2051–2057. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patterson TL, Shaw WS, Semple SJ. Reducing the Sexual Risk Behavior of HIV+ Individuals: Outcome of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25(2):137. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson JL, Coates TJ, Catania J, et al. Evaluation of an HIV risk reduction intervention among African-American homosexual and bisexual men. AIDS. 1996;10(3):319–325. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Proude EM, D’Este C, Ward JE. Randomized trial in family practice of a brief intervention to reduce STI risk in young adults. Family Practice. 2004;21(5):537–544. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, et al. Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: A multi-clinic assessment. AIDS. 2004;18(8):1179–1186. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, et al. Theory-based HIV risk reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2004;31(12):727–733. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000145849.35655.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stein JA, Nyamathi A, Kington R. Change in AIDS risk behaviors among impoverished minority women after a community-based cognitive-behavioral outreach program. Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25(6):519–533. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tudiver F, Myers T, Kurtz RG, Orr K. The talking sex project. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 1992;15(1):26–42. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Valdiserri RO, Lyter DW, Leviton LC, Callahan CM, Kingsley LA, Rinaldo CR. AIDS prevention in homosexual and bisexual men: results of a randomized trial evaluating two risk reduction interventions. AIDS. 1989;3(1):21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilson D, Mparadzi A, Lavelle S. An experimental comparison of two AIDS prevention interventions among young Zimbabweans. The Journal of social psychology. 1992;132(3):415–417. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1992.9924719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abdala N, Zhan W, Shaboltas AV, Skochilov RV, Kozlov AP, Krasnoselskikh TV. Efficacy of a brief HIV prevention counseling intervention among STI clinic patients in Russia: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS and behavior. 2013;17(3):1016–1024. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0311-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bernstein E, Ashong D, Heeren T, et al. The impact of a brief motivational intervention on unprotected sex and sex while high among drug-positive emergency department patients who receive STI/HIV VC/T and drug treatment referral as standard of care. AIDS and behavior. 2012;16(5):1203–1216. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Joseph H, et al. An online randomized controlled trial evaluating HIV prevention digital media interventions for men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e46252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Eaton L, Jooste S, Simbayi LC. Randomized clinical trial of brief risk reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. American journal of public health. 2011;101(9):e9–e17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kennedy SB, Nolen S, Pan Z, Smith B, Applewhite J, Vanderhoff KJ. Effectiveness of a brief condom promotion program in reducing risky sexual behaviours among African American men. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2013;19(2):408–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lovejoy TI, Heckman TG, Suhr JA, Anderson T, Heckman BD, France CR. Telephone-administered motivational interviewing reduces risky sexual behavior in HIV-positive late middle-age and older adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. AIDS and behavior. 2011;15(8):1623–1634. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peltzer K, Simbayi L, Banyini M, Kekana Q. HIV risk reduction intervention among medically circumcised young men in South Africa: a randomized controlled trial. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2012;19(3):336–341. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Archibald CP, Chan RK, Wong ML, Goh A, Goh CL. Evaluation of a safe-sex intervention programme among sex workers in Singapore. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1994;5(4):268–272. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Simmens SJ, Cheng TL, O’Connor K, D’Angelo LJ. A STD/HIV prevention trial among adolescents in managed care. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):107–115. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Crosby R, DiClemente RJ, Charnigo R, Snow G, Troutman A. A brief, clinic-based, safer sex intervention for heterosexual African American men newly diagnosed with an STD: a randomized controlled trial. American journal of public health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S96–S103. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gollub EL, French P, Loundou A, Latka M, Rogers C, Stein Z. A randomized trial of hierarchical counseling in a short, clinic-based intervention to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted diseases in women. Aids. 2000;14(9):1249–1255. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grimley DM, Hook EW., 3rd A 15-minute interactive, computerized condom use intervention with biological endpoints. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2009;36(2):73–78. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818eea81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, Fong GT. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2005;159(5):440–449. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, 3rd, O’Leary A. Effects on sexual risk behavior and STD rate of brief HIV/STD prevention interventions for African American women in primary care settings. American journal of public health. 2007;97(6):1034–1040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, et al. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2005;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mansfield CJ, Conroy ME, Emans SJ, Woods ER. A pilot study of AIDS education and counseling of high-risk adolescents in an office setting. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 1993;14(2):115–119. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Orr DP, Langefeld CD, Katz BP, Caine VA. Behavioral intervention to increase condom use among high-risk female adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics. 1996;128(2):288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pedlow CT. Randomized controlled trial of a brief information, motivation, and behavioral skills intervention to reduce HIV/STD risk in young women. [Dissertation]: Psychology, Syracuse University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wynendaele B, Bomba W, M’Manga W, Bhart S, Fransen L. Impact of Counselling on Safer Sex and STD Occurrence among STD Patients in Malawi. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1995;6(2):105–109. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hoffmann T, English T, Glasziou P. Reporting of interventions in randomised trials: an audit of journal instructions to authors. Trials. 2014;15:20. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Latka M, Gollub E, French P, Stein Z. Male-condom and female-condom use among women after counseling in a risk-reduction hierarchy for STD prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2000;27(8):431–437. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200009000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]