Abstract

Objective

Compare the safety and efficacy of topical gentian violet (GV) to that of nystatin oral suspension (NYS) for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OC) in HIV-1 infected adults in resource-limited settings.

Design

Multicenter, open-label, evaluator-blinded, randomized clinical trial at 8 international sites, within the AIDS Clinical Trials Group.

Study participants and Intervention

Adult HIV-infected participants with OC, stratified by CD4 cell counts and antiretroviral therapy status at study entry, were randomized to receive either GV (0.00165%, BID) or NYS (500,000 units, QID) for 14 days.

Main outcome measure(s)

Cure or improvement after 14 days of treatment. Signs and symptoms of OC were evaluated in an evaluator-blinded manner.

Results

The study was closed early per DSMB after enrolling 221 participants (target = 494). Among the 182 participants eligible for efficacy analysis, 63 (68.5%) in the GV arm had cure or improvement of OC versus 61 (67.8%) in the NYS arm, resulting in a non-sizable difference of 0.007 (95% CI: -0.129, 0.143). There was no sizable difference in cure rates between the two arms (-0.0007; 95% CI: -0.146, 0.131). No GV-related adverse events were noted. No sizable differences were identified in tolerance, adherence, quality of life, or acceptability of study drugs. In GV arm, 61% and 39% of participants reported “no” and “mild-to-moderate” staining, respectively. Cost for medication procurement was significantly lower for GV versus NYS [Median $2.51 and $19.42, respectively, P = 0.01].

Conclusions

Efficacy of GV was not statistically different than NYS, was well-tolerated, and its procurement cost was substantially less than NYS.

Keywords: Oral candidiasis, oral complications in HIV infection, gentian violet, nystatin, resource-limited setting, cost per treatment

Background

Oral candidiasis (OC) is among the most common opportunistic infections observed in HIV-infected individuals and often presents as the initial manifestation of disease [1-4]. Left untreated, OC can contribute to morbidity including esophageal disease and weight loss [5]. Recent studies conducted by the Oral HIV AIDS Research Alliance (OHARA) of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) demonstrated that OC is strongly associated with tuberculosis in HIV-infected participants, independent of CD4 count [6]. Although the incidence of OC has declined in resource-rich countries following the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [7, 8], the prevalence of OC in HIV-infected participants in resource-limited settings (RLS) remains substantial, reaching as high as 33% [9-14].

Nystatin oral suspension (NYS) is the main antifungal used to treat OC in HIV-infected participants in RLS [15-18]. To identify a low cost alternative to current treatment, our group conducted preclinical studies and found GV possesses potent anti-Candida activity [19, 20]. GV has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a topical treatment for OC in HIV-infected participants, at a concentration of 1% [21]. In an earlier study, our group reported that oral rinsing with GV at low concentrations (0.00165%, 16.5 μg/mL) was safe and well-tolerated, with no mucosal staining [22]. In the present study, we compared the safety and efficacy of topical GV to that of NYS in the treatment of OC in HIV-infected adult participants from RLS.

Methods

Design

A5265 was a multi-center phase III, randomized, open-label, evaluator-blinded clinical trial conducted in eight non-U.S. Clinical Research Sites (CRSs) of the ACTG (detailed clinical protocol is provided as a Supplemental File). Evaluation of signs and symptoms of OC was performed by a trained clinician blinded to the treatment assignment.

Study Sites

The sites participating in the protocol A5265 were: (1) University of Natal, Durban, South Africa; YRG CARE Medical Center VHS, Chennai, India; (2) Joint Clinical Research Center, Kampala, Uganda; (3) Walter Reed Project, Kericho, Kenya; (4) AMPATH at MOI University, Eldoret, Kenya; (5) Botswana Harvard Partnership/Princess Marina Hospital, Gaborone, Botswana; (6) Botswana Harvard Partnership/Scottish Livingston Hospital, Molepolole, Botswana; (7) Johns Hopkins Research Project/College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi; and (8) UZ/UCSF HIV Prevention Trials Unit, Harare, Zimbabwe. At each site, the study protocol and consent form were approved as appropriate by their local institutional review board (IRB).

Study Population

The eligibility criteria for enrollment were as follows: HIV-infected adults (≥ 18 years of age) presenting with pseudomembranous candidiasis (PC); positive identification of Candida in oral swabs at screening; negative pregnancy test performed within 48 hours prior to study entry for female study volunteers of reproductive age, a Karnofsky performance score ≥60 prior to entry [23], with ability to comply with all study procedures and follow-up after informed consent. Participants were excluded for the following reasons: proven or presumptive esophageal candidiasis at study entry; use of any investigational drug within 30 days prior to study entry; concurrent vaginal candidiasis within 21 days prior to study entry; use of inhaled or systemic corticosteroids or antifungals within 14 days prior to study entry; use of antifungal agents or other oral topical treatments during the study period; allergy/sensitivity or any hypersensitivity to GV or NYS; active illicit drug or alcohol use or dependence that would interfere with adherence to study requirements; serious illness (HIV-1 associated or not) indicating a high likelihood of death in the 30 days after study entry; predictors of early mortality (e.g. anemia, low CD4 count); previous or current history of porphyria; presence of oral warts during the screening period or at study entry; or use of full or partial dentures at study entry. Participants who failed treatment were referred for care outside of the study but continued to be followed on study; a zole therapy was most often initiated with study drug failure.

Randomization and Stratification

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to two arms (GV or nystatin), and stratified according to the following criteria: (a) screening CD4+ cell count > 200 cells/mm3 or ≤ _200 cells/mm3, (b) taking ART at the time of study entry or not taking ART at the time of study entry (and not planning to initiate ART during the study-defined 14-day treatment period).

Study Treatment

At randomization, participants were stratified by CD4+ T-cell counts (> 200 cells/mm3 or ≤ 200 cells/mm3) and ART use at the time of study entry (Yes or No) to receive topical GV (0.00165%, 5 mL swish and gargle for 2 minutes and expectorate twice daily) or NYS oral suspension (5 mL of 100,000 units/mL swish for 2 minutes and swallow, four times daily) for 14 days. Participants were instructed not to eat or drink for 30 minutes before and after the administration of study drugs.

Oral Examination and Scoring of Lesions

The oral cavity was categorized into 6 sites (Supplementary Figure 1). Severity was scored from 0 to 3 (0:no lesions, 1: scattered non-confluent lesions <2 mm in diameter, 2:multiple non-confluent lesions >2 mm in diameter, and 3: extensive confluent lesions). A composite severity score (CSS, range: 0 to 18) was obtained after adding the scores from all 6 sites. All examiners received standardized training in establishing a clinical diagnosis of PC using a published case definition [24]. A primary physician asisted by a registered nurse practitioner led the assessment at each study site.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was a single binary outcome, defined as cure (CSS = 0) or improvement (a decrease in severity of lesions) at the end of treatment. Therapy was considered to have failed if participants had no improvement or worsening of their scores, or if signs or symptoms worsened after ≥ 7 consecutive days of therapy.

Secondary endpoints included: OC symptoms (discomfort and pain), yeast colony counts, adverse events (AEs), tolerance, adherence (medication diaries and bottle counts), self-reported quality of life (QOL), acceptability of study drugs, and cost per treatment regimen. Discomfort and pain were rated on a 4-point scale (from no pain=0, mild pain=1, moderate pain=2, and severe pain=3). Cost per treatment course was calculated using a microcosting, ingredients-based approach [25]. Self-reported resource utilization including outpatient clinic visits and inpatient hospital stays at study entry and at the week 6 visit was compared between each arm. Costs for NYS also included materials and labor costs for drug preparation if acquired in concentrated form. Drug acquisition and labor costs were obtained directly from study sites and converted to 2014 U.S. Dollars (USD).

Sample Size Calculations and Data Analyses

This study was sized to estimate the difference in clinical efficacy rates between GV and NYS for the treatment of OC with appropriate precision (width of 95% CI < 0.2). Repeated CIs (RCIs) were used to control type I error. One interim analysis was conducted by utilizing a 99.7% CI and the final analysis used a 95.1% CI (constructed based on the Lan-DeMets error-spending function corresponding to the O'Brien-Fleming boundary). Assuming response rates of GV and NYS of 50% (resulting in the greatest variation and hence the widest CI), an intention-to-treat population (ITT) analysis required 494 participants after adjusting for 10% noncompliance.

The primary analysis was conducted on a modified ITT population, which was defined as participants who present with a clinical diagnosis of OC with a positive yeast culture for Candida spp. at baseline. Cases without oral exam records at week 2 were considered clinical failures. A comparison of clinical efficacy rates was performed using a 95.1% CI for the difference (reported as 95% to account for 95% simultaneous coverage probability given one interim analysis) between two proportions, with four subgroup analyses conducted based on two stratification factors (screening CD4+ count and ART use at the time of study entry). In addition, a comparison of cure rates was performed per the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) recommendation of using “cure” as the primary endpoint given the concern of staining with GV. The CIs were based on either asymptotic method when event counts were > 12 or the formula provided in Fleiss [26] where the CI was adjusted by 0.5*(1/n1 + 1/n2). These comparisons were also conducted based on observed data as sensitivity analyses.

Study Accrual and Closure

A5265 was opened to accrual on June 7, 2011, and the first subject enrolled on August 2, 2011. As of October 19, 2012, a total of 221 participants (targeted sample size=494) were enrolled. The study was halted due to the DSMB concern regarding the excessive mortality unrelated to study medications in the recruited population and subsequently the study was closed because OHARA funding was not renewed.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

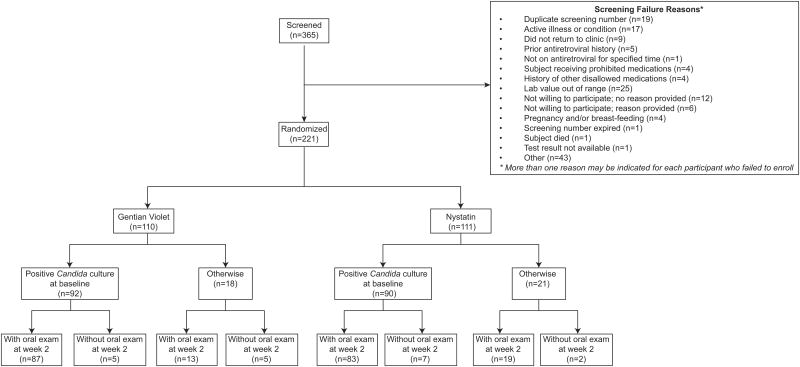

Summaries of selected baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 221 participants were enrolled into the study (Figure 1); 181 participants completed the study protocol and 40 participants discontinued the study prior to study completion (see Table 2 for reasons of study discontinuation). Among the enrolled participants, 106 (48%) were in the age group 30-39 years, and 128 (58%) were females. Moreover, 203 (92%) participants were black non-Hispanic, and 18 (8%) were Asian or Pacific Islanders. At the time of study entry, 166 (75%) participants were not taking ART and not planning to initiate ART until the study-defined 14-day treatment period was complete. The CD4 count in 175 participants (79%) was between 0-200 cells/mm3 (Median: 53 cells/mm3) and the median of baseline viral RNA titer log10[HIV RNA (cp/ml)] was 5.30. In patients with CD4 counts below 200, the median and IQR results were similar between the two treatment arms: 37 [13, 69] for GV and 43 [10, 92] for NYS; In patients with CD4 counts greater than 200, the median [IQR] were also similar between the two arms: 356 [299, 512] for GV and 371 [265, 573] for NYS.

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Gentian Violet (N=110) | Nystatin (N=111) | Total (N=221) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18-19 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (0%) |

| 20-29 | 17 (15%) | 30 (27%) | 47 (21%) | |

| 30-39 | 54 (49%) | 52 (47%) | 106 (48%) | |

| 40-49 | 21 (19%) | 17 (15%) | 38 (17%) | |

| 50-59 | 16 (15%) | 9 (8%) | 25 (11%) | |

| Over 60 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (2%) | |

| Gender | Male | 48 (44%) | 45 (41%) | 93 (42%) |

| Female | 62 (56%) | 66 (59%) | 128 (58%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Black Non-Hispanic | 97 (88%) | 106 (95%) | 203 (92%) |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 13 (12%) | 5 (5%) | 18 (8%) | |

| Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Usage at Entry | On ART | 27 (25%) | 28 (25%) | 55 (25%) |

| Not on ART | 83 (75%) | 83 (75%) | 166 (75%) | |

| CD4 Count (cells/mm3) | 0-200 | 87 (79%) | 88 (79%) | 175 (79%) |

| > 200 | 23 (21%) | 23 (21%) | 46 (21%) | |

| Baseline Log10 [HIV RNA (cp/ml)] | N | 110 | 110 | 220 |

| # missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.89 (1.31) | 5.03 (1.21) | 4.96 (1.26) | |

| Min, Max | 1.59, 6.42 | 1.59, 7.00 | 1.59, 7.00 | |

| Median | 5.21 | 5.40 | 5.30 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 4.76, 5.72 | 4.78, 5.71 | 4.77, 5.72 |

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram for the study.

Table 2. Reasons for study discontinuation in the gentian violet (GV) and nystatin (NYS) arms.

| Off-Study Reason | GV N (%*) | NYS N (%*) | Total N (%*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed protocol | 91 | (82.7%) | 90 | (81.1%) | 181 | (81.9%) |

| Death | 12 | (10.9%) | 9 | (8.1%) | 21 | (9.5%) |

| Severe debilitation, unable to continue | 0 | (0.0%) | 1 | (0.9%) | 1 | (0.5%) |

| Subject/parent not able to get to clinic | 5 | (4.5%) | 2 | (1.8%) | 7 | (3.2%) |

| Subject/parent withdrew consent prior to study completion | 0 | (0.0%) | 2 | (1.8%) | 2 | (0.9%) |

| Subject/parent not willing to adhere to study requirements | 1 | (0.9%) | 2 | (1.8%) | 3 | (1.4%) |

| ACTU unable to contact subject/parent | 1 | (0.9%) | 5 | (4.5%) | 6 | (2.7%) |

Percentages were compared to the number of enrolled participants in each group (GV = 110, NYS = 111, Total = 221)

ACTU = AIDS Clinical Trials Unit

Safety Monitoring

There were 18 participants (10 in GV group and 8 in NYS group) who experienced any signs or symptoms of grade 3 or higher AEs and 12 participants (6 in GV and 6 in NYS) who experienced new laboratory toxicity events of grade 3 or higher. In the GV arm, 1 case was reported to be probably not related to GV, while all other new signs, symptoms, laboratory events, and AEs, were not related to GV. In the NYS arm, there were 2 reported cases probably not related, 1 case possibly-related, and the rest (3) were not related to the study drug.

There were 21 deaths (12 in GV and9 in NYS), and the primary causes of death for 18 of these cases were: HIV infection or HIV-related diagnosis (15), non-HIV diagnosis (2), toxicity (1) secondary to herbal medication (Table 3). None of the deaths were considered related to study medications.

Table 3. Reasons for death in gentian violet (GV) and nystatin (NYS) treatment arms.

| Primary Cause of Death Category | GV (N, %) | NYS (N, %) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV infection or HIV-related diagnosis | 8 (67%) | 7 (78%) | 15 (71%) |

| Non-HIV diagnosis | 2 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) |

| Toxicity | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) | 1 (5%) |

| No information available | 2 (17%) | 1 (11%) | 3 (14%) |

| Total | 12 | 9 | 21 |

None of the deaths were considered related to study medications

Efficacy Analysis

Population for Efficacy Analysis

Of the 221 participants enrolled, a total of 182 (GV: 92; NYS: 90) had positive Candida culture results at baseline, and were eligible for the modified ITT efficacy analysis (Figure 1). Of these participants, 170 (GV: 87; NYS: 83) had oral exams at week 2. Cases without oral exam records at week 2 were considered as clinical failures, which included 5 participants in the GV arm and 7 in the NYS arm. For the ‘observed data’ analysis, 19 (GV: 10; NYS: 9) of the 221 (GV: 110; NYS: 111) enrolled participants did not have oral exams at week 2, thus excluded, which led to a total of 202 (GV: 100; NYS: 102) participants in the analysis (Figure 1).

Evaluation of Clinical Efficacy

We first evaluated the difference in clinical efficacy rates based on modified ITT analysis. Among the 182 participants eligible for analysis, 63 (68.5%) in the GV arm (n=92) had cure or improvement of OC compared to 61 (67.8%) in the NYS arm (n=90), resulting in a non-sizable difference (GV-NYS) of 0.007 (95% CI: -0.129, 0.143). Table 1 showed that the majority of participants were not on ART. Comparison of the two arms using a “cure” rate also showed no sizable difference (-0.0007, 95% CI: -0.146, 0.131). Sensitivity analyses based on observed data showed no sizable difference either (Table 4). Due to the sparse stratum cells presented in Table 4, no adjustment was made for the stratification in the efficacy analyses or the additional analyses below.

Table 4. Comparison of gentian violet (GV) and nystatin (NYS) in clinical efficacy and cure rates.

| Variable | GV | NYS | Diff. with 95% CI‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Event / Sample size | |||

| Clinical efficacy in the mITT | 63/92 | 61/90 | 0.007 (-0.129, 0.143) |

| On ART*; CD4§ ≤ 200 | 11/15 | 11/17 | 0.086 (-0.297, 0.469) |

| On ART; CD4 > 200 | 4/5 | 2/2 | -0.200 (-0.902, 0.502) |

| Not on ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 38/61 | 41/63 | -0.028 (-0.198, 0.142) |

| Not on ART; CD4 > 200 | 10/11 | 7/8 | 0.034 (-0.360, 0.429) |

|

| |||

| Cure in the mITT | 31/92 | 31/90 | -0.007 (-0.146, 0.131) |

| On ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 4/15 | 2/17 | 0.149 (-0.186, 0.484) |

| On ART; CD4 > 200 | 5/5 | 2/2 | 0.000 (-0.350, 0.350) |

| Not on ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 16/61 | 21/63 | -0.071 (-0.232, 0.090) |

| Not on ART; CD4 > 200 | 6/11 | 6/8 | -0.205 (-0.735, 0.326) |

|

| |||

| Clinical efficacy based on observed data | 76/100 | 73/102 | 0.044 (-0.077, 0.166) |

| On ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 12/16 | 12/18 | 0.083 (-0.281, 0.448) |

| On ART; CD4 > 200 | 9/9 | 7/10 | 0.300 (-0.091, 0.691) |

| Not on ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 43/63 | 44/63 | -0.016 (-0.178, 0.146) |

| Not on ART; CD4 > 200 | 12/12 | 10/11 | 0.091 (-0.167, 0.349) |

|

| |||

| Cure based on observed data | 37/100 | 41/102 | -0.032 (-0.167, 0.103) |

| On ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 4/16 | 2/18 | 0.139 (-0.178, 0.456) |

| On ART; CD4 > 200 | 9/9 | 7/10 | 0.300 (-0.091, 0.691) |

| Not on ART; CD4 ≤ 200 | 17/63 | 23/63 | -0.095 (-0.258, 0.067) |

| Not on ART; CD4 > 200 | 7/12 | 9/11 | -0.235 (-0.684, 0.214) |

Asymptotic 95% CI was used when event counts were > 12; Otherwise, formula by Fleiss [26] was used.

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Usage at Entry

Screening CD4 Count (cells/μL)

Additional Outcome Measures by Treatment

The analyses below were based on observed data

Staining

Evaluation of differences in staining of the oral mucosa in the GV arm revealed 61% of participants reported no staining; 28% reported mild staining (mainly the tongue); and 11% reported moderate staining of the oral cavity. Notably, no participant reported severe staining. There were no instances where GV was discontinued due to staining. No staining was observed in the NYS arm.

Evaluation of symptoms

Pain and discomfort associated with OC were evaluated at study entry, end-of-treatment, and at clinical relapse. At study entry, a total of 217 observations (106 in the GV arm; 111 in the NYS arm) were available for evaluation. At the end-of-treatment, a total of 204 observations were available to evaluate the symptoms using extended Mantel-Haenszel test between arms. The tests did not show a sizable treatment effect. A total of 8 participants had clinical relapse of OC between weeks 2 and 8 (5 in GV; 3 in NYS). All 5 participants reported no pain in the GV arm while 2 reported mild and 1 reported severe pain in the NYS arm. One participant from each arm reported severe discomfort at relapse; others had no discomfort.

Quantitative yeast colony counts

The number of colony forming units (CFUs) per milliliter was evaluated at entry, end-of-treatment, at week 6, and at clinical relapse (between weeks 2 and 8). The difference in the means of log-transformed CFUs at entry (GV – NYS, 95% CI), end-of-treatment, and at week 6 was 0.25 (-0.40, 0.89), 1.05 (0.32, 1.78), and 1.15 (-0.88, 1.17), respectively (Supplemental Table 1). At clinical relapse, 3 observations were available for each arm without marked difference in mean log CFU.

Assessment of tolerance, adherence, quality of life, acceptability, and cost comparison

There was no significant difference between the GV and NYS groups in regard to drug tolerance, adherence, self-reported QOL, and acceptability (p = 0.17, 0.83, 0.88, and 0.36, respectively). The estimated ratio of adherence between GV and NYS was 1.01 with 95% CI (0.93, 1.10), and the ratio of acceptability between the two groups was 1.03 with 95% CI (0.97, 1.10). Comparison of the cost per treatment course of GV and NYS by study CRS showed that the GV medication (requiring pharmacy preparation via reconstitution and/or dilution), procurement costs were sizably lower than treatment with NYS (no pharmacy preparation needed) [Median (Q1, Q3) = $2.51 (0.95, 3.11) and $19.42 (6.46, 36.28), respectively, p = 0.01; Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2].

Discussion

The current study was the largest evaluator-blinded, randomized clinical trial that compared the efficacy of GV to NYS in the treatment of OC in HIV-infected adults in RLS. Our results showed that both treatments resulted in high clinical efficacy rates with no sizable differences between the two groups. The efficacy rates for both GV and NYS were higher than previous studies comparing the efficacy of these two agents [27, 28]. Our secondary analyses revealed no sizable differences in tolerance, adherence, QOL, or acceptability of study drugs.

Oral NYS is commonly used in the treatment of OC in HIV-infected participants [29, 30]; however, its use is limited by bitter taste, gastrointestinal side effects, four times per day dosing, and a relatively high cost, which contribute to reduced drug adherence and lower efficacy. While there is substantial variation in procurement prices for medications across sites [31], our study showed that GV (despite required pharmacy preparation) was consistently associated with a lower cost per treatment dose compared to NYS (no pharmacy preparation needed). While labor needs may constrain healthcare in RLS, the need for pharmacy preparation for GV is counterbalanced by the substantially lower cost of GV. For example, the labor cost of preparing GV would need to be more than seven times the current estimates before total cost per GV treatment regimen reached that of NYS. In addition, the widespread availability of GV in RLS, its long-term physical and chemical stability, and the ease of preparation makes GV a viable and attractive treatment option in HIV-infected participants.

Nyst et al. [27] conducted a randomized open-label study to compare the efficacy of GV versus NYS and oral ketoconazole for the treatment of OC in AIDS participants in the Democratic Republic of Congo. There was similar efficacy among all three drugs. However, this study was limited by the small sample size and the fact that the GV concentration used was 300-fold higher than the concentration used in the current study (0.5% vs. 0.00165%, respectively), and was associated with staining of teeth and gums, oral irritation and small superficial ulcers. In a separate study, Hodgson et al. [28] compared the efficacy and tolerability of 1% and 0.00165% (as used in this study) GV and NYS mouth rinses for oral PC in pediatric HIV-infected participants in Malawi. The lower concentration of GV (0.00165%) was as effective as a 1% GV solution with fewer side effects.

Gentian violethas a long history of use and has been recommended by the WHO as a topical treatment for OC in HIV-infected participants, at a concentration of 1% [21]. However, since 1% GV strongly stains the oral cavity, its use has been associated with a stigmatizing effect. The current trial convincingly demonstrated that use of a lower concentration of GV does not lead to severe staining or discontinuation of GV treatment and that any staining noted was transient and generally mild. These results may provide an impetus for wider acceptance of GV as a treatment for OC, especially in RLS.

Deaths reported among enrolled participants in the current study that served as the basis for the DSMB halt of the study are reflective of the study population and not associated with study medications. In this regard, mortality rates of 8 to 40% have been reported in HIV/AIDS participants in the era of ART in RLS [32-36]. The median CD4 cell count of 53 cells/mm3 for study participants in our study may help explain the deaths in this patient population.

Limitations of the study include the inability to fully accrue the target enrollment, leading to a wider CI (0.27 using the estimated efficacy rates) when compared to the original design (0.20 assuming 50% response rates). Additionally, this study was limited to sub-Saharan Africa and India, and the generalization of results to other geographic sites needs to be confirmed in additional clinical trials.

In conclusion, this is the largest randomized clinical trial evaluating the use of gentian violet for treatment of oral candidiasis in HIV-infected adults in resource-limited setting. While the efficacy of gentian violet was not statistically different thannystatin, it was well-tolerated, and drug procurement was substantially less costly than nystatin for treatment of HIV-associated oral candidiasis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Map of the oral cavity.

(1) Left lower and upper labial mucosa and buccal mucosa, (2) right lower and upper labial mucosa and buccal mucosa, (3) hard palate, (4) soft palate, (5) tongue (dorsum, lateral, and ventral), (6) floor of mouth. Participating sites were encouraged to use the oral cavity diagram to assess ulcerations and staining. Both the oral examiner and clinical staff were asked to use this diagram during the oral exam and oral treatment interview, respectively.

Supplementary Figure 2. Cost per treatment course of nystatin or gentian violet.

Cost of treatment with nystatin or gentian violet were compared using non-parametric test (Mann Whitney, two-tailed) and a P-value < .05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Table 1: Quantitative fungal counts in gentian violet (GV) and nystatin (NYS) arms, evaluated in swabs collected at different time points during the study

Supplementary Table 2. Cost per treatment course (U.S. dollars) for nystatin (NYS) and gentian violet (GV).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to participants in the A5265 study, and members of the A5265 protocol team. Study A5265 was supported by the Oral HIV AIDS Research Alliance (OHARA, BRS-ACURE-S-11-000049-110229), funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (award number UM1AI068634, UM1AI068636 and UM1AI106701) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and supported by the CWRU/UH Center for AIDS Research (CFAR, NIH grant number P30 AI036219). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDCR, NIAID, or the NIH. The NCT number is NCT01427738.

The other members of the protocol team besides the co-authors: Trinh Ly, M.D. (DAIDS Medical Officer); Isaac Rodriguez-Chavez, Ph.D. (NIDCR Clinical Science Representative); Lynette Purdue, Pharm.D. (Pharmacist); Suria Yesmin, B.S. (Clinical Trials Specialist); Deborah Greenspan, B.D.S., D. Sc., Cissy Kityo, M.Sc., Johnstone Kumwenda, FRCP, Lauren Patton, D.D.S., Srikanth Tripathy, M.D., M.B.B.S. (Investigators); Flavia Miiro, M.Sc. (CSS Representative); Linda Wieclaw, B.S. (Data Manager); Jenifer Baer, R.N. (Field Representative); Christina Blanchard-Horan, Ph.D. (International Program Specialist); Laura Hovind, M.S., Aimee Willett, B.A. (Laboratory Data Managers).

The role(s) of the authors in the conducted study are outlined below:

| Author | Role on Study | |

| 1. | Pranab K Mukherjee | Writing, data analyses, conception, design |

| 2. | Huichao Chen | Data analyses and design |

| 3. | Lauren L Patton | Conception and design |

| 4. | Scott Evans | Data analyses and design |

| 5. | Anthony Lee | Data analyses and design |

| 6. | Johnstone Kumwenda | Performance (enrollment of patients) |

| 7. | James Hakim | Performance (enrollment of patients) |

| 8. | Gaerolwe Masheto | Performance (enrollment of patients) |

| 9. | Frederick Sawe | Performance (enrollment of patients) |

| 10. | Mai T Pho | Design and data analyses |

| 11. | Kenneth A Freedberg | Design and data analyses |

| 12. | Caroline H Shiboski | Conception and design |

| 13. | Mahmoud A Ghannoum | Conception, design and performance |

| 14. | Robert A Salata | Conception, design and performance |

References

- 1.Costa CR, Cohen AJ, Fernandes OF, Miranda KC, Passos XS, Souza LK, et al. Asymptomatic oral carriage of Candida species in HIV-infected patients in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2006;48:257–261. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652006000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenspan D. Treatment of oral candidiasis in HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:211–215. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel M, Shackleton JT, Coogan MM. Effect of antifungal treatment on the prevalence of yeasts in HIV-infected subjects. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:1279–1284. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patton LL, Phelan JA, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Nittayananta W, Shiboski CH, Mbuguye TL. Prevalence and classification of HIV-associated oral lesions. Oral Dis. 2002;8:98–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pienaar ED, Young T, Holmes H. Interventions for the prevention and management of oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with HIV infection in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;11:CD003940. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003940.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiboski CH, Chen H, Ghannoum MA, Komarow L, Evans S, Mukherjee PK, et al. Role of oral candidiasis in TB and HIV co-infection: AIDS Clinical Trial Group Protocol A5253. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:682–688. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton LL, McKaig R, Strauss R, Rogers D, Eron JJ., Jr Changing prevalence of oral manifestations of human immuno-deficiency virus in the era of protease inhibitor therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang YL, Lo HJ, Hung CC, Li Y. Effect of prolonged HAART on oral colonization with Candida and candidiasis. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arendorf TM, Bredekamp B, Cloete CA, Sauer G. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in 600 South African patients. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:176–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arendorf TM, Bredekamp B, Cloete C, Stephen LX. Oral soft-tissue manifestations as presenting symptom/sign of HIV infection. SADJ. 1999;54:602–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blignaut E, Raubenheimer E, van Heerden WF, Senekal R, Dreyer MJ. Oral yeast flora of a Kalahari population. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1995;50:601–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamiru HN, Naidoo S. Oral HIV lesions and oral health behaviour of HIV-positive patients attending the Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, Maseru, Lesotho. SADJ. 2002;57:479–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes CB, Wood R, Badri M, Zilber S, Wang B, Maartens G, et al. CD4 decline and incidence of opportunistic infections in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for prophylaxis and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:464–469. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225729.79610.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiboski CH. HIV-related oral disease epidemiology among women: year 2000 update. Oral Dis. 2002;8:44–48. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nebavi F, Arnavielhe S, Le Guennec R, Menan E, Kacou A, Combe P, et al. Oropharyngeal candidiasis in AIDS patients from Abidjan (Ivory Coast): antifungal susceptibilities and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analysis of Candida albicans isolates. Pathol Biol (Paris) 1998;46:307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravera M, Reggiori A, Agliata AM, Rocco RP. Evaluating diagnosis and treatment of oral and esophageal candidiasis in Ugandan AIDS patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:274–277. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vazquez JA. Therapeutic options for the management of oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in HIV/AIDS patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2000;1:47–59. doi: 10.1310/T7A7-1E63-2KA0-JKWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blignaut E, Botes ME, Nieman HL. The treatment of oral candidiasis in a cohort of South African HIV/AIDS patients. SADJ. 1999;54:605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traboulsi RS, Mukherjee PK, Ghannoum MA. In vitro activity of inexpensive topical alternatives against Candida species isolated from the oral cavity of HIV-infected patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traboulsi RS, Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Salata RA, Jurevic R, Ghannoum MA. Gentian violet exhibits activity against biofilms formed by oral Candida isolates obtained from HIV-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3043–3045. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01601-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Clinical Management of HIV/AIDS at District and PHC Levels (SEA/AIDS/101) New Delhi: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurevic RJ, Traboulsi RS, Mukherjee PK, Salata RA, Ghannoum MA. Identification of gentian violet concentration that does not stain oral mucosa, possesses anti-candidal activity and is well tolerated. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:629–633. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenzel T, Pindur G, Morsdorf S, Giacchi J. Influence of HIV-infection on the Karnofsky score and general social functioning in patients with hemophilia. Haemostasis. 1998;28:106–110. doi: 10.1159/000022420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiboski CH, Patton LL, Webster-Cyriaque JY, Greenspan D, Traboulsi RS, Ghannoum M, et al. The Oral HIV/AIDS Research Alliance: updated case definitions of oral disease endpoints. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:481–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 3rd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Cho Paik M. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Third. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyst MJ, Perriens JH, Kimputu L, Lumbila M, Nelson AM, Piot P. Gentian violet, ketoconazole and nystatin in oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in Zairian AIDS patients. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1992;72:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgson TA, Dube Q, Lewsey JD, Zinga B, Mhango T, Tembo P . 8th Biennial Congress of the European Association of Oral Medicine. Zagreb, Croatia: 2006. The efficacy and tolerability of 1% and 0.00165% gentian violet and nystatin mouth rinses for paediatric oral pseudomembranous candidosis in Malawi: a three armed RCT; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Cuesta C, Sarrion-Perez MG, Bagan JV. Current treatment of oral candidiasis: A literature review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014;6:e576–582. doi: 10.4317/jced.51798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton LL, Bonito AJ, Shugars DA. A systematic review of the effectiveness of antifungal drugs for the prevention and treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-positive patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:170–179. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.116600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinson N, Mohapi L, Bakos D, Gray GE, McIntyre JA, Holmes CB. Costs of providing care for HIV-infected adults in an urban HIV clinic in Soweto, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:327–330. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181958546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Floyd S, Marston M, Baisley K, Wringe A, Herbst K, Chihana M, et al. The effect of antiretroviral therapy provision on all-cause, AIDS and non-AIDS mortality at the population level--a comparative analysis of data from four settings in Southern and East Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:e84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–1908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogoina D, Obiako RO, Muktar HM, Adeiza M, Babadoko A, Hassan A, et al. Morbidity and mortality patterns of hospitalised adult HIV/AIDS patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: A 4-year retrospective review from Zaria, northern Nigeria. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;55:1707–1718. doi: 10.1155/2012/940580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker AS, Prendergast AJ, Mugyenyi P, Munderi P, Hakim J, Kekitiinwa A, et al. Mortality in the year following antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV-infected adults and children in Uganda and Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cid/cis797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasamba I, Baisley K, Mayanja BN, Maher D, Grosskurth H. The impact of antiretroviral treatment on mortality trends of HIV-positive adults in rural Uganda: a longitudinal population-based study, 1999-2009. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:e66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Map of the oral cavity.

(1) Left lower and upper labial mucosa and buccal mucosa, (2) right lower and upper labial mucosa and buccal mucosa, (3) hard palate, (4) soft palate, (5) tongue (dorsum, lateral, and ventral), (6) floor of mouth. Participating sites were encouraged to use the oral cavity diagram to assess ulcerations and staining. Both the oral examiner and clinical staff were asked to use this diagram during the oral exam and oral treatment interview, respectively.

Supplementary Figure 2. Cost per treatment course of nystatin or gentian violet.

Cost of treatment with nystatin or gentian violet were compared using non-parametric test (Mann Whitney, two-tailed) and a P-value < .05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Table 1: Quantitative fungal counts in gentian violet (GV) and nystatin (NYS) arms, evaluated in swabs collected at different time points during the study

Supplementary Table 2. Cost per treatment course (U.S. dollars) for nystatin (NYS) and gentian violet (GV).