Abstract

Previous data demonstrate that Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 2A (LMP2A) enhances IL-10 to promote the survival of LMP2A-expressing B cell lymphomas. Since STAT3 is an important regulator of IL-10 production, we hypothesized that LMP2A activates a signal transduction cascade that increases STAT3 phosphorylation to enhance IL-10. Using LMP2A-negative and –positive B cell lines, the data indicate that LMP2A requires the early signaling molecules of the Syk/RAS/PI3K pathway to increase IL-10. Additional studies indicate that the PI3K-regulated kinase, BTK, is responsible for phosphorylating STAT3, which ultimately mediates the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10. These data are the first to show that LMP2A signaling results in STAT3 phosphorylation in B cells through a PI3K/BTK-dependent pathway. With the use of BTK and STAT3 inhibitors to treat B cell lymphomas in clinical trials, these findings highlight the possibility of using new pharmaceutical approaches to treat EBV-associated lymphomas that express LMP2A.

Keywords: B cell, Epstein-Barr Virus, Latent Membrane Protein 2A, Interleukin-10, Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK), Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3)

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a member of the gamma herpesvirus family that infects B lymphocytes in more than 90% of the world population (Kang and Kieff, 2015; Kempkes and Robertson, 2015). While most infections are asymptomatic or result in infectious mononucleosis (Thorley-Lawson et al., 2013), EBV is associated with the development of multiple autoimmune diseases and lymphomas of the immune system (Ascherio and Munger, 2015; Thorley-Lawson and Gross, 2004). One mechanism by which Epstein-Barr virus could contribute to these diseases is by influencing B cell function and survival.

After initial infection, EBV transitions to a latent state in which few viral genes are expressed. There are multiple latency gene patterns identified in either normal latency and/or EBV-associated pathology (Price and Luftig, 2015). The EBV latency protein Latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A), which contains 12 transmembrane domains with a long amino terminal domain, is expressed in multiple programs of EBV latency (Babcock et al., 1998; Babcock, Hochberg, and Thorley-Lawson, 2000; Babcock, Miyashita-Lin, and Thorley-Lawson, 2001; Bell et al., 2006; Decker, Klaman, and Thorley-Lawson, 1996; Hochberg et al., 2004; Niedobitek et al., 1997), suggesting the importance of this protein in normal latency and EBV-associated diseases. LMP2A acts as a B cell receptor (BCR) mimic to increase the survival of latently-infected B cells (Mancao et al., 2005; Mancao and Hammerschmidt, 2007; Portis and Longnecker, 2004). Previous studies indicate that LMP2A constitutively activates many of the kinases and signal transduction molecules used by the BCR, including Syk, Ras, PI3K, BTK, and AKT (Fruehling and Longnecker, 1997; Merchant and Longnecker, 2001; Portis and Longnecker, 2004) to promote B cell survival (Merchant and Longnecker, 2001; Portis and Longnecker, 2004). Additional studies demonstrate that LMP2A signaling in B cells directly results in an increase in anti-apoptotic factors, such as BCL-2 and BCL-xL (Bultema, Longnecker, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2009; Portis and Longnecker, 2004; Swanson-Mungerson, Bultema, and Longnecker, 2010). More recently, it has become appreciated that LMP2A indirectly promotes B cell survival by increasing the production of pro-survival cytokines, such as IL-10 (Incrocci, McCormack, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2013). Due to the redundant expression of LMP2A throughout many phases of the EBV life cycle, targeting its pro-survival abilities in EBV-associated tumors may be of therapeutic benefit.

Pharmacological therapies to treat tumors typically induce the death of cells that are rapidly proliferating or by blocking signal transduction pathways that directly increase tumor cell survival (Dominguez-Brauer et al., 2015; Pistritto et al., 2016). However, an alternative approach may be to block the production of pro-survival factors, such as IL-10. Inhibiting the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10 that promotes tumor survival may provide a potential novel approach to enhance current chemotherapeutic strategies for EBV-associated lymphomas. Therefore, we sought to identify the signals required for LMP2A to increase IL-10 production in B cell lymphomas. Our findings indicate for the first time, that LMP2A activates BTK to phosphorylate STAT3 in B cell tumors, which mediates the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10. Due to the identification of new therapeutics that target BTK and STAT3 in clinical trials, these findings have important implications for innovative treatments of LMP2A-expressing B cell tumors.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

All B cell lines used in this study have been described previously (Ikeda and Longnecker, 2007). Briefly, the BJAB B cell lymphoma line was transduced with either the vector backbone alone or the vector backbone with LMP2A. Transduced cells were selected using hygromycin and gentamycin and LMP2A expression was identified in all selected cells by immunofluorescence and found to be similar in levels when compared to lymphoblastoid cell lines (Incrocci, McCormack, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2013). Independent clones were isolated and maintained in cRPMI media supplemented with hygromycin (0.4 ug/ml) (EMD Millipore) and gentamycin (2 ug/ml) (Sigma Aldrich) at 37°C/5% CO2. The lymphoblastoid cell lines LCL3 (LMP2A-positive) and ES1 (LMP2A-negative) were generously provided by Richard Longnecker (Northwestern University-Chicago, Illinois) and were maintained in cRPMI at 37° C/5% CO2.

Analysis of IL-10 production

5x104 LMP2A-negative or LMP2A-positive B cell lines described above were grown in a 96-well plate in the absence or presence of an optimized concentration of the following pharmacological inhibitors: Syk (R788-EMD Millipore, 5 uM), Ras (Manumycin A-EMD Millipore, 0.5 uM), PI3K (Wortmannin-EMD Millipore, 10 uM), STAT3 (Stattic-EMD Millipore, up to 1.75 uM), or BTK (Ibrutinib-Selleckchem, up to 10 uM). All inhibitors were initially diluted in DMSO and final dilutions were reached in cRPMI. The cells that were not exposed to inhibitor were exposed to an equivalent amount of DMSO to control for the potential effects of DMSO alone in all experiments. After 24 hours, 20 ul of supernatants were isolated for use in an LDH assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO) to analyze inhibitor toxicity and 100 ul of supernatants were isolated for analysis using the Human IL-10 Ready, Set, Go® ELISA kit (Ebioscience). All of the inhibitors used in the study did not induce toxicity at 24 hours as determined by LDH assay (data not shown), confirming that any differences seen in IL-10 levels was not due to toxicity of the assay.

Western Blot analysis for STAT3

All B cell lines (10 x 106) were incubated for 24 hours in the absence or presence of Syk (5 uM), Ras (Manumycin A- 0.5 uM), Wortmannin (10 uM), Ibrutinib (10 uM) or Stattic (1.75 uM) and then lysed in RIPA buffer (Pierce, Rockford IL) containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS, along with HaltTM Protease and Phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce, Rockford IL). Protein concentrations from cell lysates were quantified using a BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford IL) and equal amounts of protein were analyzed by Western blot. Antibodies against phosphorylated- and total-STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Massachusetts) or GAPDH (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) were diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer containing milk, followed by washes in TBST. A secondary anti-rabbit IgG-HRP conjugated Ab (Pierce, Rockford IL) diluted in blocking buffer (1:5000) was added to the blot followed by ECL imaging (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire UK) using a Bio-Rad imager. Image analysis and quantification was done using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The ratio of phosphorylated STAT3 to Total STAT3 was determined by dividing the value of the band for phosphorylated STAT3 according to ImageJ software by the value of the band for total STAT3 under different culture conditions.

Statistics

Each experiment was performed at least three times. All ELISA experiments were initially analyzed by a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Bonferonni post hoc test to compare individual groups using Prism Graphpad software. All experiments that demonstrated a p<0.05 by ANOVA and only findings that reached p<0.05 by Bonferroni comparisons were considered significant.

Results

LMP2A is a BCR mimic that directly promotes B cell survival through a RAS/PI3K dependent pathway (Portis and Longnecker, 2004) and indirectly by inducing IL-10 production in both LMP2A-expressing primary murine transgenic B cells and in B cell lymphomas (Incrocci, McCormack, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2013). An additional study at the time indicated that the Syk inhibitor, R406, blocked the enhancement of IL-10 production in EBV-positive tumor cells from post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) patients (Hatton et al., 2011). These studies suggested that LMP2A uses Syk to increase IL-10. However, PTLD cells express numerous EBV latency proteins and therefore we sought to confirm that LMP2A uses Syk to increase IL-10 by using multiple B cell lines that only express LMP2A. Two independently-derived B cell lines that express LMP2A (LMP2A1.1 and LMP2A1.2) and two LMP2A-negative control cell lines (Vector.1 and Vector.2) were exposed to the Syk inhibitor (R788, Fostamatinib) for 24 hours and IL-10 production was analyzed using ELISA. As shown in Figure 1A, the addition of the Syk inhibitor significantly decreased the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10 production. Additionally, the Syk inhibitor did not significantly affect IL-10 production by LMP2A-negative B cell lines, indicating that this effect is specific for LMP2A. Since Syk activation leads to Ras stimulation during BCR signaling (Beitz et al., 1999; Mocsai, Ruland, and Tybulewicz, 2010), we next tested if LMP2A required Ras to increase IL-10 production. As shown in Figure 1B, the addition of the Ras inhibitor, Manumycin A, also decreased the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10 production, without significantly affecting IL-10 production in the LMP2A-negative cell lines. One downstream target of Ras activation is p38K phosphorylation and signaling (Shin et al., 2005). Since p38K controls IL-10 regulation in monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (Chi et al., 2006; Foey et al., 1998; Jarnicki et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2005), we initially tested if LMP2A activates p38K in the LMP2A-expressing B cells used in this study. However, Western blot analysis of protein lysates from LMP2A-negative and –positive B cell lines indicate that LMP2A does not increase p38K phosphorylation (data not shown). Therefore, the Ras-mediated increase in IL-10 production must be via an alternative pathway downstream of Ras.

Fig 1.

LMP2A uses Syk, Ras, and PI3K to increase IL-10 production. LMP2A-negative (Vector.1 and Vector.2) and LMP2A-positive (LMP2A1.1 and LMP2A1.2) B cell lines were incubated in the absence or presence of the (A) Syk inhibitor, R788 (Fostamatinib), (B) Ras inhibitor, Manumycin A, or (C) PI3K inhibitor, Wortmannin for 24 hours and supernatants were isolated for analysis using an IL-10 ELISA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. * indicates p<0.05 when compared to LMP2A-negative B cell lines, ** indicates p<0.05 when compared to the same cell line that was incubated in the absence of inhibitor

Ras leads to the activation and signaling via PI3K in B cells. Our previous work using the PI3K inhibitor, Ly294002, suggested that LMP2A utilizes PI3K to increase IL-10 production (Incrocci, McCormack, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2013). However, due to the identification that Ly294002 can also affect NF-kB activation (Avni, Glucksam, and Zor, 2012), we wanted to confirm our previous findings through the use of the more PI3K-specific inhibitor Wortmannin (Avni, Glucksam, and Zor, 2012). Therefore, LMP2A-expressing and non-expressing B cell lines were incubated in the absence or presence of Wortmannin for 24 hours and IL-10 levels were once again analyzed by ELISA. As shown in Figure 1C, Wortmannin decreased the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10 production, confirming that LMP2A requires PI3K activation to increase IL-10 levels.

Our previous findings also indicate that LMP2A increases the levels of IL-10 RNA transcripts (Incrocci, McCormack, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2013) and therefore, we hypothesized that PI3K activation may result in the activation of a transcription factor that regulates IL-10 RNA levels. Since Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) increases IL-10 transcription (Gabrysova et al., 2014) and is regulated by PI3K (Hart et al., 2011), we hypothesized that the LMP2A-dependent activation of PI3K would result in STAT3 phosphorylation, which is a pre-requisite for STAT3 induction as a transcription factor (Harrison, 2012). To determine if LMP2A induces STAT3 activation, we analyzed the levels of STAT3 phosphorylation at tyrosine residue 705, which is critical for STAT3 dimerization and activation (Sellier et al., 2013), using Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2A, LMP2A-expressing cells demonstrate higher levels of STAT3 phosphorylation than non-LMP2A-expressing B cell lines. We also analyzed if LMP2A increased the phosphorylation of the regulatory site of STAT3 (serine 727), but we were unable to detect phosphorylation of this residue in any of the cell lines tested (data not shown), suggesting that LMP2A does not induce the phosphorylation of serine 727 to influence IL-10 production. If LMP2A-mediated activation of the Syk/Ras/PI3K pathway results in STAT3 phosphorylation and the subsequent regulation of IL-10 as suggested in Figure 1, then the addition of inhibitors to these signal transduction molecules should block STAT3 phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 2B, the addition of inhibitors to Syk, Ras, and PI3K blocked the LMP2A-mediated increase in STAT3 phosphorylation, but did not consistently affect the basal levels of STAT3 phosphorylation in non-LMP2A-expressing cells. Most importantly, we originally hypothesized that the PI3K-mediated activation of STAT3 was responsible for the LMP2A-mediated increase in IL-10 production. If this hypothesis is correct, then the addition of a STAT3 inhibitor should block the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10. When LMP2A-expressing cells were incubated in the presence of the STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic (Schust et al., 2006), the levels of STAT3 phosphorylation were decreased (Figure 2B) and the amount of IL-10 were significantly decreased in a concentration-dependent manner in only the LMP2A-expressing cells (Figure 2C), suggesting that LMP2A requires STAT3 phosphorylation to increase IL-10 production.

Fig 2.

LMP2A uses PI3K to activate STAT3 to increase IL-10 production. (A) Protein from LMP2A-negative or –positive B cell lines (10 x 106 cells) was isolated and analyzed for phosphorylated (Y705)-STAT3, total STAT3, or GAPDH by Western blot analysis. (B) Protein from LMP2A-negative or –positive B cell lines (10 x 106 cells) was isolated after a 24 hour incubation in the absence or presence of R788 (5 uM), Manumycin A (0.5 uM), Wortmannin (10 uM), or Stattic (1.75 uM). Phosphorylated (Y705)-STAT3, total STAT3, or GAPDH were analyzed by Western Blot analysis. (C) LMP2A-negative and –positive B cell lines were incubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of the STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic, for 24 hours and supernatants were isolated for analysis using an IL-10 ELISA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. For Western blot analysis, the ratio of phosphorylated (Y705)-STAT3/total STAT3 is given underneath each respective band. * indicates p<0.05 when compared to LMP2A-negative B cell lines, ** indicates p<0.05 when compared to the same cell line that was incubated in the absence of inhibitor

Recent findings indicate that the link between PI3K and STAT3 phosphorylation is mediated by TEC family kinases (Vogt and Hart, 2011). LMP2A increases the activation of the TEC family kinase, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) (Mano, 1999; Merchant and Longnecker, 2001), suggesting that this kinase may be the link connecting PI3K activation and STAT3 phosphorylation in LMP2A-expressing cell lines. If LMP2A activates BTK to enhance STAT3 phosphorylation, then a BTK inhibitor would block the LMP2A-mediated increase in STAT3 phosphorylation. To test this possibility, LMP2A-negative and –positive B cell lines were exposed to the BTK inhibitor, Ibrutinib, for 24 hours and STAT3 phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3A, the addition of Ibrutinib blocked the LMP2A-dependent phosphorylation of STAT3, without decreasing STAT3 phosphorylation in non-LMP2A-expressing cells. Furthermore, since Ibrutinib decreased STAT3 phosphorylation in LMP2A-expressing cells, we would expect that the addition of Ibrutinib would significantly inhibit the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10 production. As shown in Figure 3B, the addition of Ibrutinib decreased IL-10 production in LMP2A-expressing cells in a concentration-dependent manner, further confirming that LMP2A activates the PI3K/BTK/STAT3 pathway to increase IL-10 production in LMP2A-expressing B cells.

Fig 3.

LMP2A activates BTK to phosphorylate STAT3 and increase IL-10 production. (A) Protein from LMP2A-negative or –positive B cell lines (10 x 106 cells) was isolated after a 24 hour incubation in the absence or presence of the BTK inhibitor, Ibrutinib (10 uM). Total and phosphorylated-STAT3 were analyzed by Western Blot analysis. (B) LMP2A-negative and –positive B cell lines were incubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of Ibrutinib for 24 hours and supernatants were isolated for analysis using an IL-10 ELISA. Data in (A–B) are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. For Western blot analysis, the ratio of phosphorylated (Y705)-STAT3/total STAT3 is given underneath each respective band. * indicates p<0.05 when compared to LMP2A-negative B cell lines, ** indicates p<0.05 when compared to the same cell line that was incubated in the absence of inhibitor

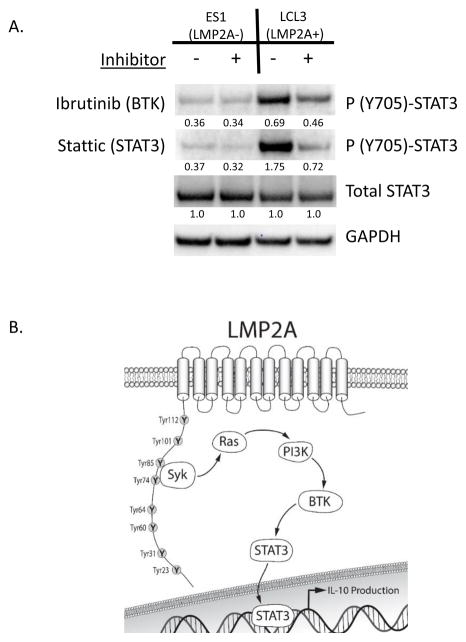

LMP2A is not expressed in isolation and therefore, it is important to determine if LMP2A increases STAT3 phosphorylation in the presence of other latency proteins. Therefore, to determine if LMP2A increases STAT3 phosphorylation in the context of latent infection, we tested whether lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) that expressed LMP2A demonstrate an increase in STAT3 phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 4A, STAT3 phosphorylation was higher in the LMP2A-positive LCL (LCL3) when compared to the LMP2A-negative lymphoblastoid cell line ES1. Furthermore, based on our studies using B cell lymphoma lines, we confirmed that the LMP2A-dependent increase in STAT3 phosphorylation was BTK-dependent. As shown in Figure 4A, the addition of Ibrutinib blocked the LMP2A-dependent increase in STAT3 phosphorylation in the LMP2A-positive LCL (LCL3), but did not show a significant effect on the LMP2A-negative LCL (ES1). These data suggest that in context of EBV latent infection, LMP2A utilizes BTK to increase the phosphorylation of STAT3. Taken together, we propose that LMP2A activates the PI3K/BTK/STAT3 pathway to enhance STAT3 phosphorylation, which may have significant impact on the survival and drug-resistance of EBV-associated tumors.

Fig 4.

LMP2A increases STAT3 phosphorylation in the context of latent EBV infection. (A) Protein from LMP2A-negative (ES1) or –positive (LCL3) lymphoblastoid cell lines (10 x 106 cells) was isolated after a 24 hour incubation in the absence or presence of Ibrutinib (1.75 uM) or Stattic (1.75 uM). Phosphorylated (Y705)-STAT3, total STAT3, or GAPDH were analyzed by Western Blot analysis. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results. For Western blot analysis, the ration of phosphorylated (Y705)-STAT3/total STAT3 is given underneath each respective band. (B) Model of the mechanism by which LMP2A increases IL-10 production. LMP2A activates Syk to increase Ras and subsequent PI3K activation. PI3K activation results in the stimulation of BTK to phosphorylate STAT3 to increase the amounts of IL-10 RNA in LMP2A-expressing cells.

Discussion

These data are the first to show that LMP2A signaling results in the phosphorylation of STAT3 through BTK signaling in B cell lymphomas. These findings are exciting in light of the fact that Ibrutinib has received breakthrough designation from the FDA to expedite clinical trials (Zucca and Bertoni, 2013) and is being used in clinical trials alone or in combination to treat B cell tumors, such as chronic myeloid leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia (Maddocks and Blum, 2014). One advantage of using BTK as a drug target for lymphoma treatment, is due to its relatively limited expression in different cell types (Mohamed et al., 2009) and therefore has exhibited limited toxicity thus far (Wang et al., 2015). Since PI3K and STAT3 are used by many different cell types (Cantley, 2002; Levy and Lee, 2002), drugs that target these signal transduction molecules may have greater side effects (Do, Mace, and Rexwinkle, 2016; Ogura et al., 2015). Therefore, our results suggest that Ibrutinib may be an asset in the treatment of EBV-associated lymphomas with minimal side effects, which has not yet been investigated. One potential EBV-associated lymphoma that may be amenable to new treatments that target BTK and STAT3 is Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (HL). EBV is detected in 40–50% of HL cases (Khan and Coates, 1994; Kuppers et al., 2002), while greater than 80–99% of HL cases are positive for EBV in AIDS patients (Bibas and Antinori, 2009). The malignant cell in HL, the Hodgkin-Reed Sternberg (HRS) cell is infected with EBV in EBV-associated HL and expresses LMP2A. These EBV-infected HL cells overexpress STAT3, when compared to EBV-negative HL (Garcia et al., 2003), suggesting that STAT3 contributes to HRS cell development and survival in EBV-associated HL. Therefore, our findings indicate that inhibition of the LMP2A-mediated increase in STAT3 by targeting BTK may provide a novel approach to current therapies.

In EBV-positive HRS cells, both LMP2A and another latency protein, LMP1, is expressed. Others have demonstrated that LMP1 can also induce STAT3 activation through Jak3-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation (Wang et al., 2010) and Protein Kinase C-δ-dependent serine phosphorylation (Kung, Meckes, and Raab-Traub, 2011). Therefore, it is interesting that EBV evolved to generate multiple pathways that result in STAT3 activation in this particular tumor and points to the critical requirement for the activation of STAT3 in these tumors. Our findings with both Ibrutinib and Stattic indicate that targeting HRS cells with these inhibitors may provide therapeutic value in the course of treatment of EBV-associated B cell tumors.

Interestingly, multiple herpesviruses induce activation of STAT3 (Punjabi et al., 2007; Sen et al., 2012). For example, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), which is a member of the gamma herpesvirus family, like EBV, also constitutively activates STAT3 during latent infection (Punjabi et al., 2007). However, in the case of KSHV, the activation of STAT3 is through the production of a soluble factor and is not directly due to signaling by KSHV latency proteins (Punjabi et al., 2007). Taken together, it appears that multiple oncogenic herpesvirus family members have evolved to utilize STAT3 activation for host cell survival. However, they achieve this goal via different mechanisms.

Our data consistently demonstrate the LMP2A significantly increases IL-10 production (Figures 1–3). Even though an autocrine loop of IL-10 production and IL-10 receptor signaling on LMP2A-expressing B cells could result in increased STAT3 phosphorylation, we believe that the increase in STAT3 phosphorylation is directly due to LMP2A for the following reasons. First, IL-10 receptor signaling induces STAT3 phosphorylation through Jak kinase activation and not BTK activation (Murray, 2006; Murray, 2007). If the increase in STAT3 phosphorylation was due to increased IL-10 receptor signaling, the BTK inhibitor would not block the increased STAT3 phosphorylation observed in LMP2A-expressing cells. Additionally, IL-10 receptor signaling decreases p38K activation (Kontoyiannis et al., 2001) and Western blot analysis did not demonstrate any change in p38K phosphorylation in LMP2A-expressing cells (data not shown). Taken together, the findings indicate that LMP2A induces the phosphorylation of STAT3 through PI3K/BTK activation.

Our previous studies demonstrate the significance of LMP2A in IL-10 production for B cell survival (Incrocci, McCormack, and Swanson-Mungerson, 2013). Additionally, it is possible that the LMP2A-mediated increase may also influence the anti-tumor response induced by cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), since IL-10 dampens cell-mediated immunity (Groux et al., 1998; Klinker and Lundy, 2012). A recent study confirms that LMP2A increases IL-10 production, but the change in IL-10 was insufficient to influence CTL activity in their study (Rancan et al., 2015). It is possible that the influence of IL-10 on CTL function may be dependent on the program of EBV latency and the interplay of latency proteins. For example, LCLs express all of the latency proteins, while Hodgkin’s lymphoma express LMP1 and LMP2A. Therefore, additional studies that assess the LMP2A-dependent increase in IL-10 on CTL activity are warranted.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate, for the first time, that LMP2A induces the phosphorylation of STAT3 through the activation of PI3K and BTK to enhance IL-10 production (Figure 4B). In light of the use of both BTK inhibitors in clinical trials, these findings potentially highlight novel pharmaceutical approaches to treat EBV-associated lymphomas that express LMP2A.

Highlights.

LMP2A stimulates the PI3K-dependent activation of BTK to phosphorylate STAT3.

The addition of the STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic, or the BTK inhibitor, Ibrutinib, blocks the LMP2A-mediated increase in STAT3 phosphorylation and IL-10 production in B cell lymphomas.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIH grant 1R15CA149690-01 (M.S.M), the Biomedical Sciences Program in the College of Health Sciences (L.B., V.S.), and the Kenneth A. Suarez Summer Research Program at Midwestern University (A.S., M.M., and S.V.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ascherio A, Munger KL. EBV and Autoimmunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;390(Pt 1):365–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avni D, Glucksam Y, Zor T. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor LY294002 modulates cytokine expression in macrophages via p50 nuclear factor kappaB inhibition, in a PI3K-independent mechanism. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(1):106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock GJ, Decker LL, Volk M, Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity. 1998;9(3):395–404. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock GJ, Hochberg D, Thorley-Lawson AD. The expression pattern of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in vivo is dependent upon the differentiation stage of the infected B cell. Immunity. 2000;13(4):497–506. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock GJ, Miyashita-Lin EM, Thorley-Lawson DA. Detection of EBV infection at the single-cell level. Precise quantitation of virus-infected cells in vivo. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;174:103–10. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-227-9:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitz LO, Fruman DA, Kurosaki T, Cantley LC, Scharenberg AM. SYK is upstream of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in B cell receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(46):32662–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AI, Groves K, Kelly GL, Croom-Carter D, Hui E, Chan AT, Rickinson AB. Analysis of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumour cells by using quantitative real-time PCR assays. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(Pt 10):2885–90. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81906-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibas M, Antinori A. EBV and HIV-Related Lymphoma. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2009;1(2):e2009032. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2009.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultema R, Longnecker R, Swanson-Mungerson M. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A accelerates MYC-induced lymphomagenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28(11):1471–6. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296(5573):1655–7. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Barry SP, Roth RJ, Wu JJ, Jones EA, Bennett AM, Flavell RA. Dynamic regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) in innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2274–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker LL, Klaman LD, Thorley-Lawson DA. Detection of the latent form of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. J Virol. 1996;70(5):3286–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3286-3289.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do B, Mace M, Rexwinkle A. Idelalisib for treatment of B-cell malignancies. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(8):547–55. doi: 10.2146/ajhp150281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Brauer C, Thu KL, Mason JM, Blaser H, Bray MR, Mak TW. Targeting Mitosis in Cancer: Emerging Strategies. Mol Cell. 2015;60(4):524–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foey AD, Parry SL, Williams LM, Feldmann M, Foxwell BM, Brennan FM. Regulation of monocyte IL-10 synthesis by endogenous IL-1 and TNF-alpha: role of the p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Immunol. 1998;160(2):920–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruehling S, Longnecker R. The immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A is essential for blocking BCR-mediated signal transduction. Virology. 1997;235(2):241–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrysova L, Howes A, Saraiva M, O’Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 expression. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;380:157–90. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43492-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JF, Camacho FI, Morente M, Fraga M, Montalban C, Alvaro T, Bellas C, Castano A, Diez A, Flores T, Martin C, Martinez MA, Mazorra F, Menarguez J, Mestre MJ, Mollejo M, Saez AI, Sanchez L, Piris MA. Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells harbor alterations in the major tumor suppressor pathways and cell-cycle checkpoints: analyses using tissue microarrays. Blood. 2003;101(2):681–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groux H, Bigler M, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. Inhibitory and stimulatory effects of IL-10 on human CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160(7):3188–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA. The Jak/STAT pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(3) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JR, Liao L, Yates JR, 3rd, Vogt PK. Essential role of Stat3 in PI3K-induced oncogenic transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(32):13247–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110486108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton O, Phillips LK, Vaysberg M, Hurwich J, Krams SM, Martinez OM. Syk activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt prevents HtrA2-dependent loss of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) to promote survival of Epstein-Barr virus+ (EBV+) B cell lymphomas. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(43):37368–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg D, Middeldorp JM, Catalina M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Thorley-Lawson DA. Demonstration of the Burkitt’s lymphoma Epstein-Barr virus phenotype in dividing latently infected memory cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(1):239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237267100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Longnecker R. Cholesterol is critical for Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A trafficking and protein stability. Virology. 2007;360(2):461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incrocci R, McCormack M, Swanson-Mungerson M. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A increases IL-10 production in mitogen-stimulated primary B-cells and B-cell lymphomas. J Gen Virol. 2013;94(Pt 5):1127–33. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.049221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnicki AG, Conroy H, Brereton C, Donnelly G, Toomey D, Walsh K, Sweeney C, Leavy O, Fletcher J, Lavelle EC, Dunne P, Mills KH. Attenuating regulatory T cell induction by TLR agonists through inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling in dendritic cells enhances their efficacy as vaccine adjuvants and cancer immunotherapeutics. J Immunol. 2008;180(6):3797–806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MS, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent genes. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e131. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempkes B, Robertson ES. Epstein-Barr virus latency: current and future perspectives. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;14:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan G, Coates PJ. The role of Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of Hodgkin’s disease. J Pathol. 1994;174(3):141–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1711740302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L, Del Rio L, Butcher BA, Mogensen TH, Paludan SR, Flavell RA, Denkers EY. p38 MAPK autophosphorylation drives macrophage IL-12 production during intracellular infection. J Immunol. 2005;174(7):4178–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinker MW, Lundy SK. Multiple mechanisms of immune suppression by B lymphocytes. Mol Med. 2012;18:123–37. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoyiannis D, Kotlyarov A, Carballo E, Alexopoulou L, Blackshear PJ, Gaestel M, Davis R, Flavell R, Kollias G. Interleukin-10 targets p38 MAPK to modulate ARE-dependent TNF mRNA translation and limit intestinal pathology. EMBO J. 2001;20(14):3760–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung CP, Meckes DG, Jr, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 activates EGFR, STAT3, and ERK through effects on PKCdelta. J Virol. 2011;85(9):4399–408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01703-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppers R, Schwering I, Brauninger A, Rajewsky K, Hansmann ML. Biology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(Suppl 1):11–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/13.s1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Lee CK. What does Stat3 do? J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1143–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddocks K, Blum KA. Ibrutinib in B-cell Lymphomas. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014;15(2):226–37. doi: 10.1007/s11864-014-0274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancao C, Altmann M, Jungnickel B, Hammerschmidt W. Rescue of “crippled” germinal center B cells from apoptosis by Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 2005;106(13):4339–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancao C, Hammerschmidt W. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A is a B-cell receptor mimic and essential for B-cell survival. Blood. 2007;110(10):3715–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mano H. Tec family of protein-tyrosine kinases: an overview of their structure and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10(3–4):267–80. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant M, Longnecker R. LMP2A survival and developmental signals are transmitted through Btk-dependent and Btk-independent pathways. Virology. 2001;291(1):46–54. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocsai A, Ruland J, Tybulewicz VL. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):387–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AJ, Yu L, Backesjo CM, Vargas L, Faryal R, Aints A, Christensson B, Berglof A, Vihinen M, Nore BF, Smith CI. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk): function, regulation, and transformation with special emphasis on the PH domain. Immunol Rev. 2009;228(1):58–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ. Understanding and exploiting the endogenous interleukin-10/STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory response. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(4):379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway: input and output integration. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2623–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedobitek G, Kremmer E, Herbst H, Whitehead L, Dawson CW, Niedobitek E, von Ostau C, Rooney N, Grasser FA, Young LS. Immunohistochemical detection of the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 2A in Hodgkin’s disease and infectious mononucleosis. Blood. 1997;90(4):1664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M, Uchida T, Terui Y, Hayakawa F, Kobayashi Y, Taniwaki M, Takamatsu Y, Naoe T, Tobinai K, Munakata W, Yamauchi T, Kageyama A, Yuasa M, Motoyama M, Tsunoda T, Hatake K. Phase I study of OPB-51602, an oral inhibitor of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, in patients with relapsed/refractory hematological malignancies. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(7):896–901. doi: 10.1111/cas.12683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistritto G, Trisciuoglio D, Ceci C, Garufi A, D’Orazi G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(4):603–19. doi: 10.18632/aging.100934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portis T, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) LMP2A mediates B-lymphocyte survival through constitutive activation of the Ras/PI3K/Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23(53):8619–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AM, Luftig MA. To be or not IIb: a multi-step process for Epstein-Barr virus latency establishment and consequences for B cell tumorigenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(3):e1004656. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjabi AS, Carroll PA, Chen L, Lagunoff M. Persistent activation of STAT3 by latent Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of endothelial cells. J Virol. 2007;81(5):2449–58. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01769-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancan C, Schirrmann L, Huls C, Zeidler R, Moosmann A. Latent Membrane Protein LMP2A Impairs Recognition of EBV-Infected Cells by CD8+ T Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(6):e1004906. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schust J, Sperl B, Hollis A, Mayer TU, Berg T. Stattic: a small-molecule inhibitor of STAT3 activation and dimerization. Chem Biol. 2006;13(11):1235–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellier H, Rebillard A, Guette C, Barre B, Coqueret O. How should we define STAT3 as an oncogene and as a potential target for therapy? JAKSTAT. 2013;2(3):e24716. doi: 10.4161/jkst.24716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen N, Che X, Rajamani J, Zerboni L, Sung P, Ptacek J, Arvin AM. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and survivin induction by varicella-zoster virus promote replication and skin pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(2):600–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114232109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin I, Kim S, Song H, Kim HR, Moon A. H-Ras-specific activation of Rac-MKK3/6-p38 pathway: its critical role in invasion and migration of breast epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(15):14675–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson-Mungerson M, Bultema R, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A imposes sensitivity to apoptosis. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 9):2197–202. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.021444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1328–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorley-Lawson DA, Hawkins JB, Tracy SI, Shapiro M. The pathogenesis of Epstein-Barr virus persistent infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3(3):227–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt PK, Hart JR. PI3K and STAT3: a new alliance. Cancer Discov. 2011;1(6):481–6. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ML, Blum KA, Martin P, Goy A, Auer R, Kahl BS, Jurczak W, Advani RH, Romaguera JE, Williams ME, Barrientos JC, Chmielowska E, Radford J, Stilgenbauer S, Dreyling M, Jedrzejczak WW, Johnson P, Spurgeon SE, Zhang L, Baher L, Cheng M, Lee D, Beaupre DM, Rule S. Long-term follow-up of MCL patients treated with single-agent ibrutinib: updated safety and efficacy results. Blood. 2015;126(6):739–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-635326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Luo F, Li L, Yang L, Hu D, Ma X, Lu Z, Sun L, Cao Y. STAT3 activation induced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein1 causes vascular endothelial growth factor expression and cellular invasiveness via JAK3 And ERK signaling. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(16):2996–3006. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucca E, Bertoni F. Toward new treatments for mantle-cell lymphoma? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):571–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1307596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]