Abstract

Background

Secretoglobin (SCGB) 3A2, a novel lung-enriched cytokine-like secreted protein of small molecular weight, was demonstrated to exhibit various biological functions including anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and growth factor activities. Anti-inflammatory activity was uncovered using the ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation model. However, further validation of this activity using knockout mice in a different allegic inflammation model is necessary in order to establish the anti-allergic inflammatory role for this protein.

Methods

Scgb3a2-null mice were subjected to nasal inhalation of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract for 5 days per week, for 5 consecutive weeks; control mice received nasal inhalation of saline as a comparator. Airway inflammation was assessed by histological analysis, inflammatory cell numbers and various Th2-type cytokine levels in lungs and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids by qRT-PCR and ELISA, respectively.

Results

Exacerbated inflammation was found in the airway of Scgb3a2-null mice subjected to house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation as compared with saline-treated control groups. All the inflammation endpoints were increased in the Scgb3a2-null mice. The Ccr4 and Ccl17 mRNA levels were higher in house dust mite-treated lungs of Scgb3a2-null mice than wild-type mice or saline-treated Scgb3a2-null mice, whereas no changes were observed for Ccr3 and Ccl11 mRNA levels.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that SCGB3A2 has an anti-inflammatory activity in the house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation model, in which SCGB3A2 may modulate the CCR4-CCL17 pathway. SCGB3A2 may provide a useful tool to treat allergic airway inflammation, and further studies warranted on the levels and function of SCGB3A2 in asthmatic patients.

Keywords: SCGB3A2, lung-enriched cytokine-like protein, anti-inflammation, anti-fibrosis, growth factor, house dust mite, allergic airway inflammation, mouse model

Introduction

Secretoglobin (SCGB) 3A2 is a member of the SCGB gene superfamily of cytokine-like secretory proteins of small molecular weight [1]. SCGB proteins are found only in mammalian lineages, and at high concentrations in secretions such as lung, lacrimal gland, salivary gland, prostate, and uterus [2]. However their biological functions are not well understood. SCGB proteins are thought to play a role in the modulation of inflammation, tissue repair, and tumorigenesis [2, 3]. SCGB3A2 is predominantly expressed in the epithelial cells of the trachea, bronchus, and bronchiole of lung [4]. SCGB3A2 plays a role in embryonic lung development, and inflammation and fibrosis of lung [5–11]. SCGB3A2 is also suggested as a candidate marker for lung adenocarcinoma [12, 13]. However, the functional mechanisms for these SCGB3A2 activities are largely unknown.

The human SCGB3A2 gene is located on chromosome 5q31-q34, which harbors a number of genes associated with bronchial asthma, for example the genes coding for interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13 and beta 2 adrenoreceptor [14]. Moreover, a functional promoter polymorphism -112G/A is associated with bronchial asthma in Japanese [15] and Asian populations [16]. In addition, plasma SCGB3A2 level is associated with severity of bronchial ashma [17], while the concentration of SCGB3A2 in sputum of asthma patients is elevated [18]. These results suggested a role for SCGB3A2 in lung inflammation. This was demonstrated experimentally using the ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation mouse model, in conjunction with recombinant adenovirus-expressing SCGB3A2, where SCGB3A2 was suppressed airway allergic inflammation [8]. Further, Scgb3a2-null (Scgb3a2−/−) mice when subjected to OVA-induced airway inflammation model, exhibited increased airway inflammation as compared with their respective wild-type littermates [10].

The current study was carried out to determine using Scgb3a2−/− mice whether SCGB3A2 exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in an airway inflammation model of house dust mite (HDM), one of the most prevalent allergens with asthma and rhinitis [19, 20]. The results confirmed that SCGB3A2 serves as an anti-inflammatory agent in allergic airway inflammation in mice.

Materials and Methods

Mouse model of HDM-induced airway inflamation

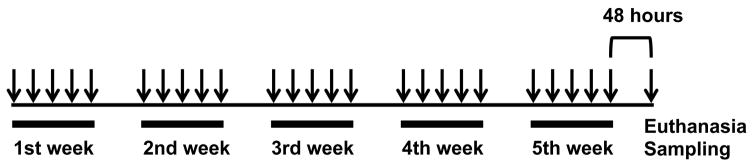

Scgb3a2−/− mice, as previously described [10], were backcrossed ten times onto a C57BL/6NCr background. 8- to 9-week-old female Scgb3a2−/− mice and their respective wild-type littermates (15–25 mice/group, up to 5 mice per cage) were placed in the same cage and maintained under standard specific-pathogen-free conditions. Airway inflammation was induced by nasal inhalation of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract (Greer laboratories, Lenoir, NC, 25 μg of protein in 10 μl of saline) under isoflurane anesthesia for 5 days per week, for 5 consecutive weeks (fig. 1) [21]. Control C57BL/6NCr mice received nasal inhalation of 10 μl of saline as a comparator. Mice were subjected to necropsy for end-point analysis at 48 hours after the last HDM administration. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was obtained by intratracheal instillation of 1 ml PBS in the lung. The lung tissues were pooled in RNAlater (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) and stored at −80°C until RNA purification. Cytospin preparations of BALF were centrifuged onto glass slides through Shandon Cytofunnels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) at 700 rpm for 10 min. Cell differentiation was demonstrated on over 200 cells stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and analyzed by microscopy. All mouse experiments were performed following the guidelines for animal use issued by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Animal Care and Use Committee.

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocol. 8- to 9-week-old female Scgb3a2−/− mice and their respective wild-type littermates received nasal inhalation of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract (25 μg of protein in 10 μl of saline) for 5 days per week, for 5 consecutive weeks. Control C57BL/6NCr mice received nasal inhalation of 10 μl of saline as a comparator. Mice were subjected to necropsy at 48 hours after the last HDM administration.

Antibodies

Anti-SCGB3A2 antibody used for immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry was produced by immunizing Escherichia coli-produced hexahistidine tagged protein containing full-length mouse SCGB3A2, as previously described [4]. The anti-GAPDH antibody 6C5 (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used to detect GAPDH as a loading control on immunoblots.

Histological analysis

Lungs were inflated with 10% buffered formalin under a pressure of 25 cm H2O, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm. Lung sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Lung lesions as well as perivascular and peribronchiolar cuffing with inflammatory cells were graded using H&E sections in blind fashion as follows: 0 for no lesions, 1 for 0–25%, 2 for 26–50%, 3 for 51–75%, and 4 for 76–100% of the lung section involved. The histological grades depended on the extent of the lesion in the lung and the severity of the lesion itself.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA from the lung of each mouse was individually isolated using Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek Corp., Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with small modifications: 10 mM dithiothreitol was added to a lysis buffer, and 0.5 μL of RNaseOUT Recombinant Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Life Technologies) was added to each elution tube before eluting RNA. Purified RNA was kept at −80 °C until use. Oligo(dT)-primed cDNAs were reverse-transcribed from 1.0 μg total RNAs by using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies) according to the supplier’s protocol. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed in triplicate using the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with PerfeCta SYBR Green FastMix, ROX (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are shown in Table S1. The ΔΔCT method was used to calculate relative expression levels using that of Ppia (peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A)) mRNA as a control.

ELISA assays

Mouse IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, and CCL17 protein levels were quantified by using ELISA kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and the CCR4 protein levels were measured with an ELISA kit from LifeSpan BioSciences (Seattle, WA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Assay ranges of each ELISA kit was 7.8–500 (IL-4), 15.6–1,000 (IL-5), 46.9–3,000 (IL-9), 7.8–500 (IL-13), 31.2–2,000 (CCL17), and 78–5,000 (CCR4) pg/ml.

HDM restimulation of mediastinal lymph node cultures and measurement of Th2 cytokines

Single cell suspensions of mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) from either saline- or HDM-challenged mice were prepared by filtering through a 100 μm-cell strainer, as previously described [22]. After red blood cells were lysed with Red Blood Cell Lysing Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich), MLN cells were re-suspended in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 250 ng/mL amphotericin B and 3.5 μL/L 2-mercaptoethanol. Cells were seeded at 4 × 106 cells per well in 96-well plate, and re-stimulated with HDM (100 μg/mL) or saline for 96 hours before collection. Mouse IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 production was measured by ELISA kits (R&D Systems) as described above.

Data analysis

Data are shown as means ± SD. Levels of significance for comparison between samples were determined by two-way ANOVA. P-values of <0.05 were considered asstatistically significant. Graph Pad Prism version 7 was used for analysis.

Results

Scgb3a2 deficiency exacerbates HDM-induced airway inflammation

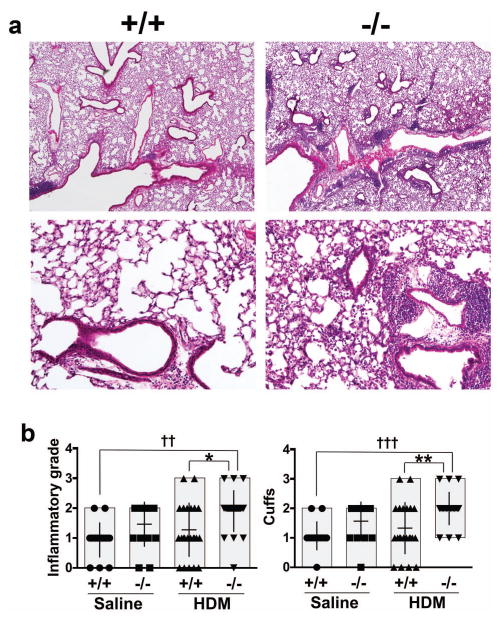

To understand the role of SCGB3A2 in HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation, HDM or saline as control was nasally administered to Scgb3a2−/− and wild-type mice 5 days/week for 5 consecutive weeks. Hitological analysis using H&E-stained sections of mouse lungs from HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− and wild-type demonstrated that the inflammation in Scgb3a2−/− mouse lungs was observed in much wider areas and was more severe than those of wild-type mice (fig. 2a). In fact, the inflammatory grade and perivascular and peribronchiolar cuffing of these lung lesions were higher with statistical differences in HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mice than their wild-type littermates (fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Histological analysis of HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation. a Representative lung H&E sections of wild-type (+/+) and Scgb3a2−/− mice (−/−) in HDM-induced airway inflammation. Original magnifications: 40 × (upper panel), 200 × (lower panel). b Inflammatory grade (left), and perivascular and peribronchiolar cuffs (right) of wild-type (+/+) and Scgb3a2−/− (−/−) mouse lungs of control (Saline) and challenged group (HDM). Significant difference from wild-type mice: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01, from sailine-treated mice: ††, p<0.01; †††, p<0.001 by two-way ANOVA.

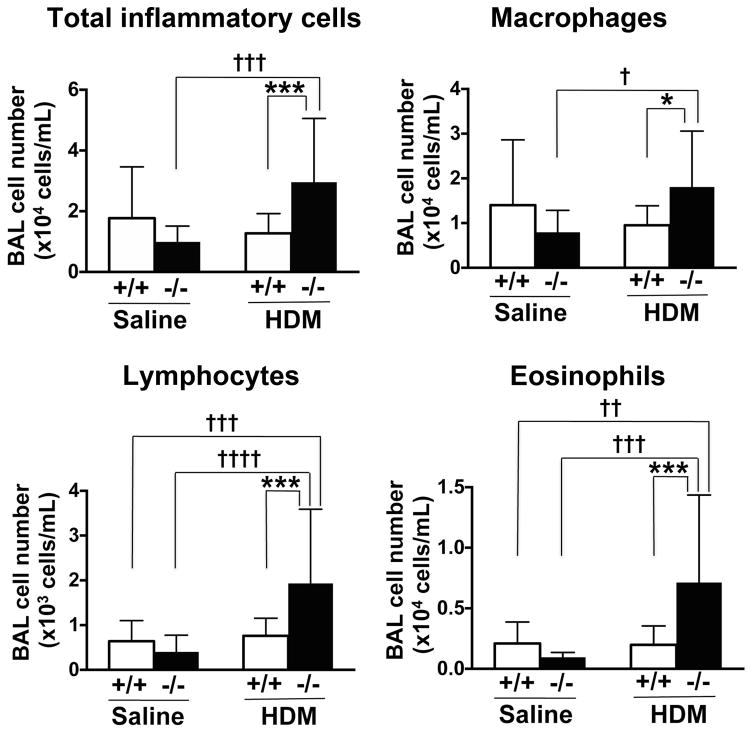

Increased BAL cells in Scgb3a2 knockout mice

The total number of inflammatory cells, and the number of lymphocytes, macrophages and eosinophils in BAL fluid, were significantly increased in HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mice as compared with wild-type (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

BALF inflammatory cell numbers. Number of total inflammatory cells, lymphocytes, macrophages and eosinophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from wild-type (+/+) and Scgb3a2−/− (−/−) mice are shown in control (Saline) and challenged (HDM) groups. Significant difference from wild-type mice: *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001, from sailine-treated mice: †, p<0.05, ††, p<0.01; †††, p<0.001; ††††, p<0.0001 by two-way ANOVA.

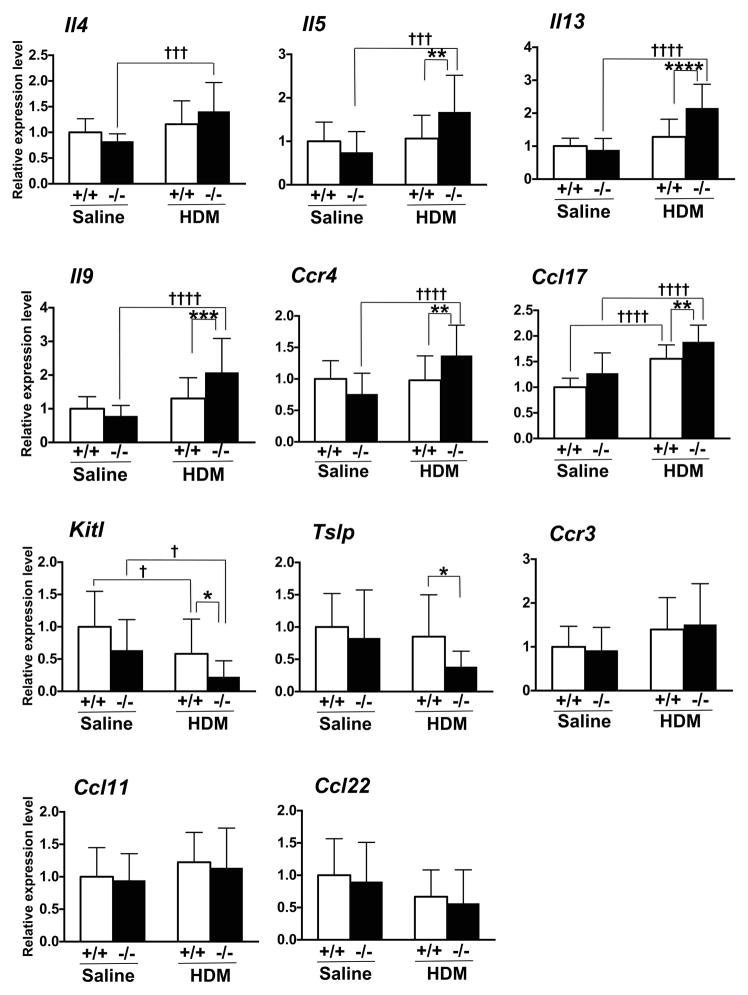

Increased cytokines in Scgb3a2 knockout mice

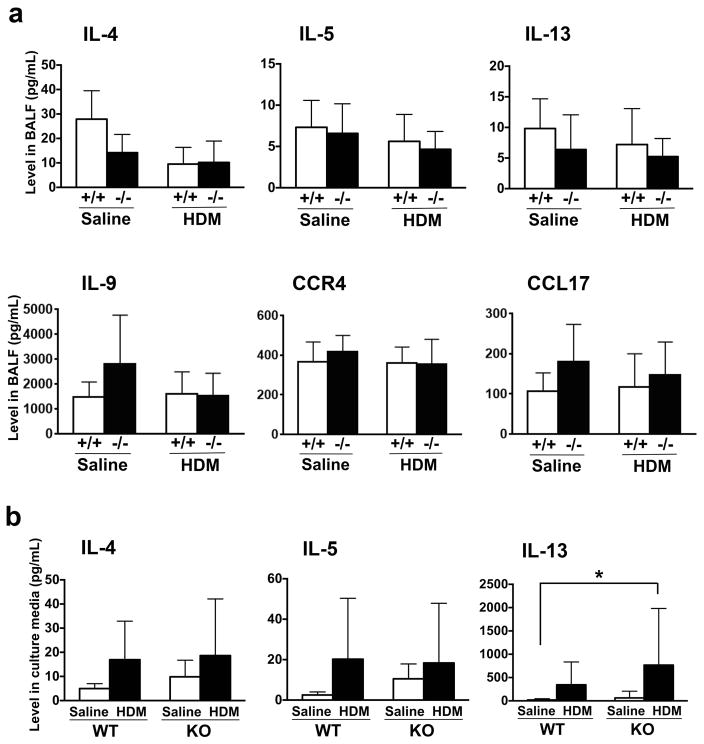

The expression levels of mRNAs encoding various cytokines were determined from various groups of mouse lungs. Messenger RNAs for IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, CCR4 (chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 4), and CCL17 (chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 17) were increased in HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mouse lungs as compared with saline-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mouse lungs (fig. 4). Further, most of these mRNAs were significantly increased in HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mouse lungs as compared with HDM-challenged wild-type mouse lungs. There were no differences in mRNA levels for these cytokines between HDM-challenged and saline-challenged wild-type mouse lungs. In contrast, the expression levels of mRNAs for Kit ligand (Kitl, also called as stem cell factor, Scf) were decreased in HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− as well as wild-type mouse lungs as compared with saline-challenged groups of mice, and HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− as compared with HDM-challenged wild-type mouse lungs. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (Tslp) was also decreased in HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mouse lungs as compared with HDM-challenged wild-type mouse lungs. No differences were observed in the expression levels of Ccr3, Ccl11, and Ccl22 mRNAs. ELISA analysis was used to measure levels of IL-4, IL-5 IL-13, IL-9, CCR4, and CCL17 proteins in BALF from saline- or HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− and wild-type mouse lungs (fig. 5a). There were no statistically significant differences between the two lines of mice within the same treatment, nor between saline- and HDM-challenged groups within the same genotypes. When IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 levels were examined using concentrates of ex vivo cultures of mediastinal lymph node (MLN) cells, the significant differences were observed for IL-13 between HDM-treated knockout and saline-treated wild-type mice (fig. 5b).

Fig. 4.

Expression levels of Th2 cell cytokine mRNAs. The expression levels in the lungs of wild-type (+/+) and Scgb3a2−/− (−/−) mice are shown in control (Saline) and challenged (HDM) groups. Relative expression levels of each gene in the lung were measured by qRT-PCR and normalized for that of Ppia. The value of saline-challenged wild-type lungs is set as 1. Significant difference from wild-type mice: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; and ****, p<0.0001, from sailine-treated mice: †, p<0.05; †††, p<0.001; ††††, p<0.0001 by two-way ANOVA.

Fig. 5.

Expression levels of Th2 cell cytokine proteins. a Th2 cell cytokine concentrations in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from wild-type (+/+) and Scgb3a2−/− (−/−) mice, which were challenged with control (Saline) and HDM. b Th2 cell cytokine productions with re-stimulation of saline or HDM in the culture media of primary mediastinal lymphocytes from HDM-challenged wild-type (WT) and Scgb3a2−/− (KO) mice. Expression levels of each protein in BALF and culture media were measured by ELISA. *, p<0.05 by two-way ANOVA.

Discussion

The SCGB superfamily proteins are believed to play a role in inflammation [2, 3]. The present study shows that HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation is increased in Scgb3a2−/− mouse lungs compared with those of wild-type mice. This is in good agreement with previous results demonstrating that SCGB3A2 has an anti-inflammatory acitivity using the ovalubumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation mouse model in conjunction with intranasal administration of recombinant adenovirus expressing SCGB3A2 [8]. Further, when Scgb3a2−/− mice were subjected to OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation model, they exhibited exacerbated lung inflammation [10]. Since HDM is one of the most prevalent allergen with asthma and rhinitis [19, 20], the present results using HDM-induced allergic inflammation model demonstrate higher relevance of SCGB3A2 in asthma.

The exacerbated lymphocytic and eosinophilic airway inflammation was related to increases in Th2 responses, as revealed by Il5, Il13, and Il9 expression in the lung. Similarly, Ccr4 and Ccl17 expression was increased in the lung, wheareas Ccr3 and Ccl11 (eotaxin-1) expression was not changed. CCL17, mainly secreted from dendritic cells, recruits T cells via CCR4, but CCL11 recruits eosinophils via CCR3 [23]. CCR3 modulates the early stages of allergen-induced Th2-mediated airway inflammation, while CCR4 is primarily responsible for the long-term recruitment of Th2 cells to the lung in response to chronic allergen stimulation including HDM [24, 25]. Since increased Ccr4 and Ccl17 were obtained whereas no increase was observed for Ccr3 and Ccl11 in lungs of HDM-treated Scgb3a2−/− mice as compared with wild-type controls, SCGB3A2 may contribute to modulation of the CCR4-CCL17 pathway.

On the other hand, the expression of Kitl (Scf) and Tslp were decreased in HDM-treated-Scgb3a2−/− mice as compared with wild-type mice. While the reason for this decrease is not known, it suggests that SCGB3A2 may play a role in modulating the expression of Kitl and Tslp in the HDM-induced mouse airway inflammation model. In asthmatic patients, the expression of KITL and TSLP in the airways is increased [26–29], while KITL and TSLP are known to promote Th2 cytokine-mediated airway inflammation in asthma [26, 28]. These facts may suggest a reason why HDM-induced inflammation was not severe but mild in the current study using Scgb3a2−/− mice.

While the current study demonstrated that Scgb3a2−/− mice are more susceptible to HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation, the allergic response was in general low. Levels of IL-9, CCR4, and CCL17 protein in the ex vivo cultures of mediastinal lymph nodes could not be determined either due to not high enough concentrations above the detection limit, or not sufficient amount of samples available. It is known that C57BL/6 mice are not very sensitive to allergens including HDM [30]. Indeed, similar low response of Scgb3a2−/− mice on the C57BL/6NCr background was observed in the OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation model [10].

In relation to this, even though mRNA levels were found to be significantly different, the levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-9, CCR4, and CCL17 proteins in BALF as well as the ex vivo culture concentrates of mediastinal lymph node cells (for the first three cytokines), did not show any significant differences between HDM-treated Scgb3a2−/− vs. wild-type mouse lungs, and/or between saline- and HDM-treated Scgb3a2−/− or wild-type mice. We believe that for some cytokines, notably, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, the discrepancy found between mRNA and protein levels was partly due to differences in the sensitivity of the detection methods between mRNAs and proteins of generally low expression levels, typical of these cytokines. While changes in expression levels of low abundance mRNAs could be relatively easily detected by qRT-PCR, the protein levels were close to the ELISA detection limit and thus the differences were not easily detected. Further, in the current study, we used 5 weeks HDM-challenged female mice on the C57BL/6NCr background. Another study reported an induction of immunological tolerance in female C57BL/6 background mice challenged with HDM for 5 consecutive weeks using a protocol similar to ours [31]. In this study, IL-4 and IL-5 protein concentrations in BALF were not changed between the HDM-challenged mice and PBS-challenged control mice despite the increased inflammatory cells and histological inflammatory scores in the HDM-challenged mice. However, in this study, they did not determine the lung mRNA levels for these cytokines. In the lungs of HDM-challenged Scgb3a2−/− mice, the immunological tolerance might be one of the reasons for the discrepancy found in the relative mRNA and protein levels. It is worthwhile to note that the mRNA levels were determined using lung tissues whereas protein levels were determined using BALF, which are not exactly the same source. Immunological tolerance might have different influences on the transcription and secretion of these cytokines. Another possible reason for the discrepancy among gene expression, inflammation and protein levels in our study is that HDM contains numerous compounds which may induce continued innate immune responses resulting in persistent inflammation despite of apparent development of airway tolerance to HDM. In order to address these questions, levels of Th2 cytokines in acute as well as chronic phase in addition to the current sub-acute phase need to be investigated. Nevertheless, the current results clearly show that Scgb3a2−/− mice have exacerbated HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation.

Dust mites and their waste products are one of the most common causes of allergy and asthma [20]. Together, the current study suggests that SCGB3A2 expressed in lung may be protective to these disorders and exogenous SCGB3A2 could be a potential therapeutic reagent for the treatment of bronchial asthma. Levels of SCGB3A2 expression in the lung may play a role in the development and/or pathogenesis of asthma, a possibility that warrants further investigation in asthmatics.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Stewart Levine and Xianglan Yao (National Heart, Lung andBlood Institute, Bethesda, MD) for their advice and help on experiments using the house dust mite-induced allergic inflammation model and ex vivo cultures of mediastinal lymph node cells. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute (ZIABC010449).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Klug J, Beier HM, Bernard A, Chilton BS, Fleming TP, Lehrer RI, Miele L, Pattabiraman N, Singh G. Uteroglobin/Clara cell 10-kDa family of proteins: nomenclature committee report. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;923:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson BC, Thompson DC, Wright MW, McAndrews M, Bernard A, Nebert DW, Vasiliou V. Update of the human secretoglobin (SCGB) gene superfamily and an example of ‘evolutionary bloom’ of androgen-binding protein genes within the mouse Scgb gene superfamily. Hum Genomics. 2011;5:691–702. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-6-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee AB, Zhang Z, Chilton BS. Uteroglobin: a steroid-inducible immunomodulatory protein that founded the Secretoglobin superfamily. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:707–725. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niimi T, Keck-Waggoner CL, Popescu NC, Zhou Y, Levitt RC, Kimura S. UGRP1, a uteroglobin/Clara cell secretory protein-related protein, is a novel lung-enriched downstream target gene for the T/EBP/NKX2. 1 homeodomain transcription factor. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:2021–2036. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurotani R, Okumura S, Matsubara T, Yokoyama U, Buckley JR, Tomita T, Kezuka K, Nagano T, Esposito D, Taylor TE, Gillette WK, Ishikawa Y, Abe H, Ward JM, Kimura S. Secretoglobin 3A2 suppresses bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by transforming growth factor beta signaling down-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19682–19692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurotani R, Tomita T, Yang Q, Carlson BA, Chen C, Kimura S. Role of secretoglobin 3A2 in lung development. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:389–398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1104OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai Y, Winn ME, Zehmer JK, Gillette WK, Lubkowski JT, Pilon AL, Kimura S. Preclinical evaluation of human secretoglobin 3A2 in mouse models of lung development and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L10–22. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00037.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiba Y, Kurotani R, Kusakabe T, Miura T, Link BW, Misawa M, Kimura S. Uteroglobin-related protein 1 expression suppresses allergic airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:958–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-456OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai Y, Yoneda M, Tomita T, Kurotani R, Okamoto M, Kido T, Abe H, Mitzner W, Guha A, Kimura S. Transgenically-expressed secretoglobin 3A2 accelerates resolution of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:72. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kido T, Yoneda M, Cai Y, Matsubara T, Ward JM, Kimura S. Secretoglobin superfamily protein SCGB3A2 deficiency potentiates ovalbumin-induced allergic pulmonary inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:216465. doi: 10.1155/2014/216465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai Y, Kimura S. Secretoglobin 3A2 Exhibits Anti-Fibrotic Activity in Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Model Mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tachihara-Yoshikawa M, Ishida T, Watanabe K, Sugawara A, Kanazawa K, Kanno R, Suzuki T, Niimi T, Kimura S, Munakata M. Expression of secretoglobin3A2 (SCGB3A2) in primary pulmonary carcinomas. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2008;54:61–72. doi: 10.5387/fms.54.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurotani R, Kumaki N, Naizhen X, Ward JM, Linnoila RI, Kimura S. Secretoglobin 3A2/uteroglobin-related protein 1 is a novel marker for pulmonary carcinoma in mice and humans. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niimi T, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Srisodsai A, Zimonjic DB, Keck-Waggoner CL, Popescu NC, Kimura S. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the mouse gene (Scgb3a1, alias Ugrp2) that encodes a member of the novel uteroglobin-related protein gene family. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;97:120–127. doi: 10.1159/000064067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niimi T, Munakata M, Keck-Waggoner CL, Popescu NC, Levitt RC, Hisada M, Kimura S. A polymorphism in the human UGRP1 gene promoter that regulates transcription is associated with an increased risk of asthma. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:718–725. doi: 10.1086/339272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie H, Wu M, Shen B, Niu Y, Huo Y, Cheng Y. Association between the -112G/A polymorphism of uteroglobulin-related protein 1 gene and asthma risk: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:721–727. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Wang X, Saito J, Tanino Y, Ishida T, Iwaki D, Fujita T, Kimura S, Munakata M. Plasma UGRP1 levels associate with promoter G-112A polymorphism and the severity of asthma. Allergol Int. 2008;57:57–64. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-07-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van De Velde V, Courtens W, Bernard A. Development of a new sensitive ELISA for the determination of uteroglobin-related protein 1, a new potential biomarker. Biomarkers. 2010;15:619–624. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2010.508842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi VD, Davidson C, Asaduzzaman M, Nahirney D, Vliagoftis H. House dust mite interactions with airway epithelium: role in allergic airway inflammation. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:262–270. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biagtan M, Viswanathan R, Bush RK. Immunotherapy for house dust mite sensitivity: where are the knowledge gaps? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:482. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0482-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao X, Dai C, Fredriksson K, Lam J, Gao M, Keeran KJ, Nugent GZ, Qu X, Yu ZX, Jeffries N, Lin J, Kaler M, Shamburek R, Costello R, Csako G, Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG, Remaley AT, Levine SJ. Human apolipoprotein E genotypes differentially modify house dust mite-induced airway disease in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L206–215. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00110.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fredriksson K, Mishra A, Lam JK, Mushaben EM, Cuento RA, Meyer KS, Yao X, Keeran KJ, Nugent GZ, Qu X, Yu ZX, Yang Y, Raghavachari N, Dagur PK, McCoy JP, Levine SJ. The very low density lipoprotein receptor attenuates house dust mite-induced airway inflammation by suppressing dendritic cell-mediated adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2014;192:4497–4509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes PJ. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:183–192. doi: 10.1038/nri2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lloyd CM, Delaney T, Nguyen T, Tian J, Martinez AC, Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. CC chemokine receptor (CCR)3/eotaxin is followed by CCR4/monocyte-derived chemokine in mediating pulmonary T helper lymphocyte type 2 recruitment after serial antigen challenge in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;191:265–274. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perros F, Hoogsteden HC, Coyle AJ, Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Blockade of CCR4 in a humanized model of asthma reveals a critical role for DC-derived CCL17 and CCL22 in attracting Th2 cells and inducing airway inflammation. Allergy. 2009;64:995–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redhu NS, Gounni AS. Function and mechanisms of TSLP/TSLPR complex in asthma and COPD. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:994–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glück J, Rymarczyk B, Kasprzak M, Rogala B. Increased Levels of Interleukin-33 and Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin in Exhaled Breath Condensate in Chronic Bronchial Asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;169:51–56. doi: 10.1159/000444017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Da Silva CA, Reber L, Frossard N. Stem cell factor expression, mast cells and inflammation in asthma. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2006;20:21–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Muhsen SZ, Shablovsky G, Olivenstein R, Mazer B, Hamid Q. The expression of stem cell factor and c-kit receptor in human asthmatic airways. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:911–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasue M, Yokota T, Suko M, Okudaira H, Okumura Y. Comparison of sensitization to crude and purified house dust mite allergens in inbred mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1998;48:346–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bracken SJ, Adami AJ, Szczepanek SM, Ehsan M, Natarajan P, Guernsey LA, Shahriari N, Rafti E, Matson AP, Schramm CM, Thrall RS. Long-Term Exposure to House Dust Mite Leads to the Suppression of Allergic Airway Disease Despite Persistent Lung Inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2015;166:243–258. doi: 10.1159/000381058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]