Abstract

Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) is one of the most devastating pathogens that cost huge economic losses in soybean production worldwide. Due to the duplicated genome, clustered and highly homologous nature of R genes, as well as recalcitrant to transformation, soybean disease resistance studies is largely lagging compared with other diploid crops. In this review, we focus on the major advances that have been made in identifying both the virulence/avirulence factors of SMV and mapping of SMV resistant genes in soybean. In addition, we review the progress in dissecting the SMV resistant signaling pathways in soybean, with a special focus on the studies using virus-induced gene silencing. The soybean genome has been fully sequenced, and the increasingly saturated SNP markers have been identified. With these resources available together with the newly developed genome editing tools, and more efficient soybean transformation system, cloning SMV resistant genes, and ultimately generating cultivars with a broader spectrum resistance to SMV are becoming more realistic than ever.

Keywords: soybean, soybean mosaic virus, disease resistance, virus-induced gene silencing, SNP, mapping

Overview

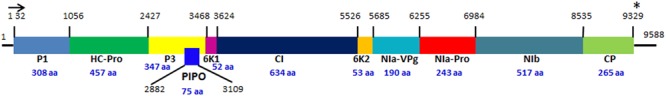

Soybean [Glycine max L. (Merrill)] is one of the most important sources of edible oil and proteins. Pathogen infections cause annual yield loss of $4 billion dollars in the United States alone1. Among these pathogens, Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) is the most prevalent and destructive viral pathogen in soybean production worldwide (Hill and Whitham, 2014). SMV is a member of the genus Potyvirus in the Potyviridae family and its genome is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA, encoding at least 11 proteins (Figure 1): potyvirus 1 (P1), helper-component proteinase (HC-Pro), potyvirus 3 (P3), PIPO, 6 kinase 1(6K1), cylindrical inclusion (CI), 6 kinase 2 (6K2), nuclear inclusion a-viral protein genome-linked (NIa-VPg), nuclear inclusion a-protease (NIa-Pro), nuclear inclusion b (Nib), and coat protein (CP) (Eggenberger et al., 1989; Jayaram et al., 1992; Wen and Hajimorad, 2010). Numerous SMV isolates have been classified into seven distinct strains (G1 to G7) in the United States based on their differential responses on susceptible and resistant soybean cultivars (Cho and Goodman, 1979, Table 1), while in China, 21 strains (SC1–SC21) have been classified (Wang et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2005; Li et al., 2010). The relationship between G strains in the United States and SC strains in China has not been fully established yet. SMV resistance is conditioned by complex gene families. Multiple independent resistance loci with different SMV strain specificities have been identified, and most of them are non-Toll interleukin receptor- nucleotide binding site-leucine rich repeat (TIR-NBS-LRR) type R genes (Hill and Whitham, 2014). So far, three independent loci, Rsv1, Rsv3, and Rsv4 in the United States and many Rsc loci in China, have been reported for SMV resistance. However, none of these genes has been cloned and their identities remain to be revealed.

FIGURE 1.

The genome organization of Soybean mosaic virus. The diagram was drawn based on the nucleotide sequence of SMV N strain (Eggenberger et al., 1989). The colored boxes represent 11 proteins encoded by SMV genome. The black lines at the 5′ and 3′ ends represent 5′ and 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The horizontal arrow and the star indicate the start and stop codons of the SMV polypeptide, respectively. The numbers above the vertical lines indicate the start positions of the SMV proteins. The sizes of the SMV proteins (the numbers of amino acids) are indicated by the blue numbers below the protein names. The PIPO embedded in the P3 is shown by the overlapping dark blue box with the start and stop positions labeled, respectively. The diagram is not drawn in scale.

Table 1.

Summary of soybean-SMV studies.

| Resistant locus | Chromosome location | Type of resistance gene | Strain specificity | Avirulent factor(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rsvl | 13 (Yu et al., 1994; Gore et al., 2002) |

NBS-LRR type (Yu et al., 1994, 1996; Khatabi et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013) |

Resistant to: Gl–G4 susceptable to: G5–G7 (Chen et al., 1991) |

He-Pro and P3 (Eggenberger et al., 2008; Hajimorad et al., 2008) |

| Cl (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011b; Wen et al., 2011) |

||||

| P3 (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011b) | ||||

| Rsv3 | 14 (Jeong et al., 2002; Shi et al., 2008) |

CC- NBS-LRR type (Suh et al., 2011) |

Resistant to: G5–G7 susceptable to: G1–G4 (Jeong et al., 2002)< |

Cl (Seo et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009a; Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011b) P3 (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011a,b) |

| Rsv4 | 2 (Hayes et al., 2000; Saghai Maroof et al., 2010) | Novel class (Ilut et al., 2016) |

Resistantto: Gl–G7 (Chen et al., 1993; Ma et al., 1995) | P3 (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011a,b; Khatabi et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015) |

Mapping of SMV Resistant Loci

Complex Nature of Rsv1 Loci in Soybean

Rsv1 was originally identified in the soybean line PI 96983 (Kiihl and Hartwig, 1979), and it confers extreme resistance (ER) to SMV-G1 through G6 but not to SMV-G7 (Chen et al., 1991; Hajimorad and Hill, 2001; Table 1). Multiple Rsv1 alleles including Rsv1-y, Rsv1-m, Rsv1-t, Rsv1-k, and Rsv1-r have been identified from different soybean cultivars with differential reactions to SMV G1–G7 strains (Chen et al., 2001). Rsv1 was initially mapped to soybean linkage group F on chromosome 13 (Yu et al., 1994) and two classes of NBS-LRR sequences (classes b and j) were identified in this resistance gene cluster (Yu et al., 1996). A large family of homologous sequences of the class j Nucleotide biinding site-leucine rich repeat (NBS-LRRs) clustered at or near the Rsv1 locus (Jeong et al., 2001; Gore et al., 2002; Peñuela et al., 2002). Six candidate genes (1eG30, 5gG3, 3gG2, 1eG15, 6gG9, and 1gG4) in PI96983 were mapped to a tightly clustered region near Rsv1, three of them (3gG2, 5gG3, and 6gG9) were completely cloned and sequenced (GenBank accession no. AY518517–AY518519). Among the three genes, 3gG2 was found to be a strong candidate for Rsv1 (Hayes et al., 2004). When 3gG2, 5gG3, and 6gG93 were simultaneously silenced using Bean pod mottle virus -induced gene silencing (BPMV-VIGS), the Rsv1-mediated resistance was compromised, confirming that one or more of these three genes is indeed the Rsv1 (Zhang et al., 2012). Because, the sequence identities of these three R genes are extremely high along the entire cDNAs, it is impossible to differentiate which one(s) is Rsv1.

Several studies indicate that two or more related non-TIR-NBS-LRR gene products are likely involved in the allelic response of several Rsv1-containing lines to SMV (Hayes et al., 2004; Wen et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013). Wen et al. (2013) generated two soybean lines, L800 and L943, derived from crosses between PI96983 (Rsv1) and Lee68 (rsv1) with distinct recombination events within the Rsv1 locus. The L800 line contains a single PI96983-derived member 3gG2, confers ER against SMV-N (an avirulent isolate of G2 strain). In contrast, the line L943 lacks 3gG2, but contains a suite of five other NBS-LRR genes allows limited replication of SMV-N at the inoculation site. Domain swapping experiments between SMV-N and SMV-G7/SMV-G7d demonstrate that at least two distinct resistance genes at the Rsv1 locus, probably belonging to the NBS-LRR class, mediate recognition of HC-Pro and P3, respectively (Khatabi et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013).

Rsv3 Is Most Likely a NBS-LRR Type Resistant Gene

Rsv3 was originated from “L29,” a ‘Williams’ isoline derived from Hardee (Bernard et al., 1991; Gunduz et al., 2000). The diverse soybean cultivars carrying Rsv3 alleles condition resistance to SMV G5 through G7, but not G1 through G4 (Jeong et al., 2002; Table 1). Rsv3 locus was firstly mapped between markers A519F/R and M3Satt on MLG B2 (chromosome 14) by Jeong et al. (2002), and was subsequently mapped on MLG-B2 with a distance of 1.5 cM from Sat_424 and 2.0 cM from Satt726 (Shi et al., 2008). The 154 kbp interval encompassing Rsv3 contains a family of closely related coiled-coil NBS-LRR (CC-NBS-LRR) genes, implying that the Rsv3 gene most likely encodes a member of this gene family (Suh et al., 2011).

Rsv4 Likely Belongs to a Novel Class of Resistance Genes

Rsv4 confer resistance to all 7 SMV strains (Chen et al., 1993; Ma et al., 1995). It was identified in soybean cultivars V94-5152 and mapped to a 0.4 cM interval between the proximal marker Rat2 and the distal marker S6ac, in a ∼94 kb haplotype block on soybean chromosome 2 (MLG D1b++W) (Hayes et al., 2000; Saghai Maroof et al., 2010; Ilut et al., 2016). A haplotype phylogenetic analysis of this region suggests that the Rsv4 locus in G. max is recently introgressed from G. soja (Ilut et al., 2016). Interestingly, this interval did not contain any NB-LRR type R genes. Instead, several genes encoding predicted transcription factors and unknown proteins are present within the region, suggesting that Rsv4 most likely belongs to a novel class of resistance gene (Hwang et al., 2006; Ilut et al., 2016).

The Other SMV Resistant Genes

Many Rsc loci have been identified. The resistance genes Rsc-8 and Rsc-9, which confer resistance to strains SC-8 and SC-9 respectively, have been mapped to the soybean chromosomes 2 (MLG D1b+W) (Wang et al., 2004). The interval of Rsc-8 was estimated to be 200 kb and contains 17 putative genes and five of them, Glyma02g13310, 13320, 13400, 13460, and 13470 could be the candidates of Rsc-8 based on their predicted functions and expression patterns (Wang et al., 2011). The Rsc-15 resistant gene was mapped between Sat_213 and Sat_286 with distances of 8.0 and 6.6 cM to the respective flanking markers on chromosome 6 (Yang and Gai, 2011). The resistance gene Rsc-7 in the soybean cultivar Kefeng No.1 was mapped to a 2.65 mega-base (Mb) region on soybean chromosome 2 (Fu et al., 2006) and was subsequently narrowed down to a 158 kilo-base (Kb) region (Yan et al., 2015). Within 15 candidate genes in the region, one NBS-LRR type gene (Glyma02g13600), one HSP40 gene (Glyma02g13520) and one serine carboxypeptidase-type gene (Glyma02g13620) could be the candidates for Rsc-7. The allelic relationship between the Rsv loci and the Rsc loci has yet to be determined.

Despite numerous efforts, none of the SMV resistant genes has been cloned and their identities remain to be identified. This reflects the complex nature of the resistant genes in palaeopolyploid soybean, in which 75% of the genes are present in multiple copies (Schmutz et al., 2010). This statement is reinforced by a recent finding that the soybean cyst nematode (SCN) resistance mediated by the Rhg1 is conditioned by copy number variation of a 31-kilobase segment, in which three different novel genes are present (Cook et al., 2012). There are 1–3 copies of the 31-kilobase segment per haploid genome in susceptible varieties, but 10 tandem copies in resistant varieties (Cook et al., 2012). The presence of more copies of the 31-kb segment in resistant varieties increases the expressions of this set of the 3 genes and thus conferes the resistance (Cook et al., 2012, 2014).

Identification of Avirulent Factors in Different Smv Strains that are Specifically Recognized By Different Rsv Gene Products

Avirulent Factors for Rsv1

SMV isolates are classified into seven strains (G1–G7) based on phenotypic reactions on a set of differential soybean cultivars (Cho and Goodman, 1982). The modification of avirulence factors of plant viruses by one or more amino acid substitutions can convert avirulence to virulence on hosts containing resistance genes and therefore, can be used as an approach to determine the avirulence factor(s) of a specific resistant gene.

Rsv1, a single dominant resistance gene in soybean PI 96983 (Rsv1), confers ER against SMV-G1 through G6 but not to SMV-G7 (Chen et al., 1991; Hajimorad and Hill, 2001; Table 1). SMV-N (an avirulent isolate of strain G2) elicits ER whereas strain SMV-G7 provokes a lethal systemic hypersensitive response (LSHR) (Hajimorad et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2004). SMV-G7d, an evolved variant of SMV-G7 from lab, induces systemic mosaic (Hajimorad et al., 2003). Serial passages of a large population of the progeny in PI 96983 resulted in emergence of a mutant population (vSMV-G7d), which can evade Rsv1-mediated recognition and the putative amino acid changes that potentially responsible for the mutant phenotype is initially tentatively narrowed down to HC-Pro, coat protein, PI proteinase or P3 (Hajimorad et al., 2003; Seo et al., 2011) and was later mapped to P3 through domain swapping between the pSMV-G7 and pSMV-G7d (Hajimorad et al., 2005). The amino acids 823, 953, and 1112 of the SMV-G7d are critical in evading of Rsv1-mediated recognition (Hajimorad et al., 2005, 2006). By generating a series of chimeras between SMV-G7 and SMV-N in combination with site-directed mutagenesis, Eggenberger et al. (2008) and Hajimorad et al. (2008) independently showed that gain of virulence on Rsv1-genotype soybean by an avirulent SMV strains requires concurrent mutations in both P3 and HC-Pro and HC-Pro complementation of P3 is essential for SMV virulence on Rsv1-genotype soybean (Table 1). A key virulence determinant of SMV on Rsv1-genotype soybeans that resides at polyprotein codon 947 overlaps both P3 and a PIPO-encoded codon. This raises the question of whether PIPO or P3 is the virulence factor. Wen et al. (2011) confirmed that amino acid changes in P3, and not the overlapping PIPO-encoded protein, which is embedded in the P3 cistron, determine virulence of SMV on Rsv1-genotype soybean. Chowda-Reddy et al. (2011b) constructed a chimeric infectious clone of G7, in which the N-ternimal part of CI was swapped with the corresponding part of G2. Compared with wildtype G7, this chimeric strain lost virulence on Rsv1-genotype plant but gained infectivity on Rsv3-genotype plant, indicating an essential role of CI for breaking down both Rsv1- and Rsv3-mediated resistance (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011b). Together, it appears that P3, HC-Pro and possibly CI are virulent determinants for Rsv1-mediated resistance (Table 1).

Avirulent Factors for Rsv3

It has been proven that cytoplasmic inclusion cistron (CI) of SMV serves as a virulence and symptom determinant on Rsv3-genotype soybean and a single amino acid substitution in CI was found to be responsible for gain or loss of elicitor function of CI (Seo et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009a). Analyses of the chimeras by exchanging fragments between avirulent SMV-G7 and the virulent SMV-N showed that both the N- and C-terminal regions of the CI cistron are required for Rsv3-mediated resistance and the N-terminal region of CI is also involved in severe symptom induction in soybean (Zhang et al., 2009a). In addition to CI, P3 has also been reported to play an essential role in virulence determination on Rsv3-mediated resistance (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011a,b; Table 1).

Avirulent Factor for Rsv4

Gain of virulence analysis on soybean genotypes containing Rsv4 genes showed that virulence on Rsv4 carrying cultivars was consistently associated with Q1033K and G1054R substitutions within P3 cistron, indicating that P3 is the SMV virulence determinant on Rsv4 and one single nucleotide mutation in the P3 protein is sufficient to compromise its elicitor function (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011b; Khatabi et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). However, the sites involved in the virulence of SMV on Rsv4-genotype soybean vary among strains (Wang et al., 2015).

It is clear now that P3 plays essential roles in virulence determination on Rsv1, Rsv3, and Rsv4 resistant loci, while CI is required for virolence on Rsv1 and Rsv3 genotype soybean plants (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011a,b). These results imply that avirulent proteins from SMV might interact with the soybean R gene products at a converged point. This evolved interactions sometimes could give SMV advantage in breaking resistance conferred by different SMV resistant genes simply by mutations within a single viral protein. On the other hand, since multiple proteins are involved in virulence on different resistant loci, concurrent mutantions in multiple proteins of SMV are required to evade the resistance conferred by different SMV resistant genes. The likelihood of such naturally occuurred concurrent mutations in different viral proteins is low. Therefore, integration of all three SMV resistant genes in a single elite soybean cultivar may provide long-lasting resistance to SMV in soybean breeding practice (Chowda-Reddy et al., 2011b).

Gain of Virulence By SMV on a Resistant Soybean Genotype Results in Fitness Loss in a Previously Susceptible Soybean Genotype

It seems that it is a common phenomenon that gain of virulence mutation(s) by an avirulent SMV strain on a resistant genotype soybean is associated with a relative fitness loss (reduced pathogenicity or virulence) in a susceptible host (Khatabi et al., 2013; Wang and Hajimorad, 2016). The majority of experimentally evolved mutations that disrupt the avirulence functions of SMV-N on Rsv1-genotype soybean also results in mild symptoms and reduced virus accumulation, relative to parental SMV-N, in Williams82 (rsv1), demonstrating that gain of virulence by SMV on Rsv1-genotype soybean results in fitness loss in a previously susceptible soybean genotype, which is resulted from mutations in HC-Pro, and not in P3 (Khatabi et al., 2013; Wang and Hajimorad, 2016). It has been also demonstrated that gain of virulence mutation(s) by all avirulent viruses on Rsv4-genotype soybean is associated with a relative fitness penalty for gaining virulence by an avirulence strain (Wang and Hajimorad, 2016). Thus, it seems that there is a cost for gaining virulence by an avirulence strain.

The Soybean Lines Carrying Multiple Rsv Genes Display Broader Spectrum of Resistance Against SMV

Soybean line PI486355 displays broad spectrum resistance to various strains of SMV. Through genetic studies, Ma et al. (1995) identified two independently inherited SMV resistant genes in PI486355. One of the genes allelic to the Rsv1 locus (designated as Rsv1-s) has dosage effect: the homozygotes conferring resistance and the heterozygotes showing systemic necrosis to SMV-G7. The other gene, which is epistatic to the Rsv1, confers resistance to strains SMV-G1 through G7 and exhibits complete dominance over Rsv1. The presence of this gene in PI486355 inhibits the expression of the systemic necrosis conditioned by the Rsv1 alleles.

Soybean cultivar Columbia is resistant to all known SMV strains G1-G7, except G4. Results from allelism tests demonstrate that two genes independent of the Rsv1 locus are present in Columbia, with one allelic to Rsv3 and the other allelic to none of the known Rsv genes (Ma et al., 2002). Plants carrying both genes were completely resistant to both G1 and G7, indicating that the two genes interact in a complementary fashion (Ma et al., 2002). The resistance conditioned by these two genes is allele dosage-dependent, plants heterozygous for either gene exhibiting systemic necrosis or late susceptibility.

Tousan 140 and Hourei, two soybean accessions from Japan, and J05, a accession from China, carry both Rsv1 and Rsv3 alleles and are resistant to SMV-G1 through G7 (Gunduz et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2011).

These results indicate that integration of more than one Rsv genes into one cultivar can confers a broader spectrum of resistance against SMV. Therefore, pyramiding multiple Rsv genes in elite soybean cultivars could be one of the best approaches to generate durable SMV resistance with broader spectrum.

The Host Factors that are Involved in SMV Resistance

The Host Components in R Gene-Mediated Defense Responses are Conserved in Rsv1-Mediated ER Against SMV

The key components in R gene mediated disease resistant signaling pathway have been identified in model plant Arabidopsis, among which, RAR1 (Required for Mla 12 Resistance), SGT1(Suppressor of G2 Allele of Skp1) and HSP90 (Heat Shock Protein 90) are the most important ones (Belkhadir et al., 2004). Using BPMV-VIGS, it has been shown that Rsv1-mediated ER against SMV in soybean requires RAR1 and SGT1 but not GmHSP90, suggesting although soybean defense signaling pathways recruit structurally conserved components, they have distinct requirements for specific proteins (Fu et al., 2009). However, Zhang et al. (2012) showed that silencing GmHSP90 using BPMV-VIGS compromised Rsv1-mediated resistance. In addition, silencing GmEDR1 (Enhanced Disease Resistance 1), GmEDS1 (Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 1), GmHSP90, GmJAR1 (Jasmonic Responsive 1), GmPAD4 (Phytoalexin Deficient 4), and two genes encoding WRKY transcription factors (WRKY6 and WRKY 30), all of which are involved in defense pathways in model plant Arabidopsis, Rsv1-mediated ER was also compromised (Table 2). These results suggest that the host components required for R gene-mediated resistant signaling pathways are conserved across plant species.

Table 2.

Host factors participate in SMV resistance.

| Host factors | Biological functions | Type of resistance | Positive or negative Roles | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmHSP90, GmRARl | Defense signaling | Rsvl-mediated | Positive | Fu et al., 2009; |

| GmSGTl, GmEDSl, GmEDRl, GmJARl, | Zhang et al., 2012 | |||

| GmPAD4, GmWRKY6, GmWRKY30 | ||||

| GmMPK4 | Defense signaling | Basal | Negative | Liu et al., 2011 |

| GmMPK6 | Defense signaling | Basal | Positive/negative | Liu et al., 2014 |

| GmHSP40.1 | Co-chaperone | Basal | Positive | Liu and Whitham, 2013 |

| GmPP2C | ABA signaling | Rsv3-mediated | Positive | Seo et al., 2014 |

| GmAKT2 | K+ channel | Basal | Positive | Zhou et al., 2014 |

| GmCNXl | Moco biosynthesis | Basal | Positive | Zhou et al., 2015 |

| GmelF5A | Translation initiation | flsi/3-mediated | Positive | Chen et al., 2016a |

| GmeEFla | Translation elongation | Basal | Negative | Luan et al., 2016 |

| GmAGOl | Gene silencing | Silencing-mediated | Positive | Chen et al., 2015 |

| GmSGS3 | Gene silencing | Silencing-mediated | Positive | Chen et al., 2015 |

Conserved but Divergent Roles of MAPK Signaling Pathway in SMV Resistance

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades play important roles in disease resistance (Meng and Zhang, 2013). The function of MAPK signaling pathways in disease resistance was investigated in soybean using BPMV-VIGS (Liu et al., 2011, 2014, 2015). Among the plants silenced for multiple genes in MAPK pathway, the plants silenced for the GmMAPK4 and GmMAPK6 homologs displayed strong phenotypes of activated defense responses (Liu et al., 2011, 2014). Consistent with the activated defense response phenotypes, these plants were more resistant to SMV compared with vector control plants (Liu et al., 2011, 2014), indicating that both genes play critical negative roles in basal resistance or PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) in soybean. The constitutively activated defense responses has been reported for mpk4 mutant in Arabidopsis (Petersen et al., 2000) and the positive role of MPK6 in defense responses is well-documented (Meng and Zhang, 2013). However, the negative role of MAKP6 homologs has not been reported previously (Liu et al., 2014), indicating that both conserved and distinct functions of MAPK signaling pathways in immunity are observed between Arabidopsis and soybean.

Identifications of the Other Host Factors that Play Critical Roles in SMV Resistance

Numerous host factors participate in defense responses in plants. Identification of these factors may facilitate rationale design of novel resistant strategies. Recently, it has been shown that silencing GmHSP40.1, a soybean nuclear-localized type-III DnaJ domain-containing HSP40, results in increased infectivity of SMV, indicating a positive role of GmHSP40.1 in basal resistance (Liu and Whitham, 2013). A subset of type 2C protein phophatase (PP2C) gene family, which participate ABA signaling pathway, is specifically up-regulated during Rsv3-mediated resistance (Seo et al., 2014). Synchronized overexpression of GmPP2C3a using SMV-G7H vector inhibits virus cell-to-cell movement mediated by callose deposition in an ABA signaling-dependent manner, indicating that GmPP2C3a functions as a key regulator of Rsv3-mediated resistance (Seo et al., 2014). An ortholog of Arabidopsis K+ weak channel encoding gene AKT2, was significantly induced by SMV inoculation in the SMV highly resistant genotype, but not in the susceptible genotype (Zhou et al., 2014). Overexpression of GmAKT2 not only significantly increased K+ concentrations in young leaves but also significantly enhanced the resistance against SMV, indicating alteration of K+ transporter expression could be a novel molecular approach for enhancing SMV resistance in soybean (Zhou et al., 2014). Molybdenum cofactor (Moco) is required for the activities of Moco-dependant enzymes. Cofactor for nitrate reductase and xanthine dehydrogenase (Cnx1) is known to be involved in the biosynthesis of Moco in plants. Soybean plants transformed with Cnx1 enhanced the enzyme activities of nitrate reductase (NR) and aldehydeoxidase (AO) and resulted in an enhanced resistance against various strains of SMV (Zhou et al., 2015). The differentially expressed genes in Rsv1 genotype in response to G7 infection have been identified (Chen et al., 2016a). Knocking down one of the identified genes, the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A (eIF5A), diminished the LSHR and enhanced viral accumulation, suggesting an essential role of eIF5A in the Rsv1-mediated LSHR signaling pathway. Eukaryotic elongation factor 1A (eEF1A) is a well-known host factor in viral pathogenesis. Recently, Luan et al. (2016) showed that silencing GmeEF1A inhibits accumulation of SMV and P3 protein of SMV interacts with GmeEF1A to facilitate its nuclear localization and therefore, promotes SMV pathogenicity.

Small RNA Pathways in SMV Resistance

miRNAs Participate in SMV Resistance

Small RNAs play a fundamental role in anti-viral defense. Three miRNAs, miR160, miR393 and miR1510, which have been previously shown to be involved in disease resistance in other plant species, have been identified as SMV-inducible miRNAs through small RNA sequencing approach (Yin et al., 2013), implying that these three miRNAs might play roles in SMV resistance. Chen et al. (2015) recently showed that the expression of miRNA168 gene is specifically highly induced only in G7-infected PI96983 (incompatible interaction) but not in G2- and G7-infected Williams 82 (compatible interactions). Overexpression of miR168 results in cleavage of miR168-mediated AGO1 mRNA and severely repression of AGO1 protein accumulation (Chen et al., 2015). Silencing SGS3, an essential component in RNA silencing, suppressed AGO1 siRNA, partially recovers the repressed AGO1 protein, and alleviates LSHR severity in G7-infected Rsv1 soybean (Chen et al., 2015). These results strongly suggest that miRNA pathway is involved in G7 infection of Rsv1 soybean, and LSHR is associated with repression of AGO1.

Chen et al. (2016b) recently performed small RNA (sRNA)-seq, degradome-seq and as well as a genome-wide transcriptome analysis to profile the global gene and miRNA expression in soybean in response to three different SMV isolates. The SMV responsive miRNAs and their potential cleavage targets were identified and subsequently validated by degradome-seq analysis, leading to the establishment of complex miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks. The information generated in this study provides insights into molecular interactions between SMV and soybean and offer candidate miRNAs and their targets for further elucidation of the SMV infection process.

Improving SMV Resistance through Generating RNAi Transgenic Lines Targeted for SMV Genome

The multiple soybean cultivars transformed with an RNA interference (RNAi) construct targeted for SMV HC-Pro displayed a significantly enhanced resistance against SMV (Gao et al., 2015). Soybean plants transformed with a single RNAi construct expressing separate short hairpins or inverted repeat (IR) (150 bp) derived from three different viruses (SMV, Alfalfa mosaic virus, and Bean pod mottle virus) confer robust systemic resistance to these viruses (Zhang et al., 2011). This strategy makes it easy to incorporate additional short IRs in the transgene, thus expanding the spectrum of virus resistance. As the cases in the other plant species, these studies demonstrate that RNA silencing is obviously the most effective approach for SMV resistance.

VIGS Is a Powerful Tool to Overcome Gene Redundancy in Soybean

Bean pod mottle virus -induced gene silencing system has been proven successful in gene function studies in soybean (Zhang et al., 2009b, 2010; Liu et al., 2015). There are four GmMAPK4 homologs that can be divided into two paralogous groups (Liu et al., 2011). The sequence identities of ORFs within the groups are greater than 96%, whereas the identities between the groups are 88.7% (Liu et al., 2015). The BPMV-VIGS construct used for silencing GmMAPK4 by Liu et al. (2011) actually can silence all four of the isoforms simultaneously. When only one parologous group was silenced by using construct targeted for the 3′ UTR (the sequence identity of the 3′ UTRs between the two parologous groups is less than 50%), the activated defense response was not observed, indicating that silencing the four GmMAPK4 isoforms simultaneously is necessary for activating defense responses in soybean. Using the same approach, it has been differentiated that GmSGT1-2 but not GmSGT1-1 is required for the Rsv1-mediated ER against SMV (Fu et al., 2009). Thus, VIGS is currently the most powerful tool in overcoming the gene redundancy in soybean.

Concluding Remarks

As none of the SMV resistant gene has been cloned so far, it is not possible to generating resistant soybean plants simply by transforming the resistant genes. In addition, due to the rapid evolution in avirulence/effector genes, the resistance conditioned by R genes will be overcome quickly (Choi et al., 2005; Gagarinova et al., 2008). Therefore, there is urgent need for a better solution in generating long-lasting SMV resistance with wide spectrums. As the first step, the identities of different Rsv genes need to be revealed and the key components in SMV resistant signaling pathway need to be identified. Cutting edge functional genomics tools and technologies have been proven successful in cloning of SCN resistant genes Rhg4 (Liu et al., 2011). TILLING coupled with VIGS and RNA interference confirmed that a mutation in the Rhg4, a serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) gene, is responsible for Rhg4 mediated resistance to SCN (Liu et al., 2011). VIGS has been proven useful in interrogating gene functions and can overcome gene redundancy in soybean (Liu et al., 2015). It has been shown recently that knocking out all three TaMLO homoeologs simultaneously in hexaploid bread wheat using TALEN and CRISPR-CAS9 resulted in heritable broad-spectrum resistance to powdery mildew (Wang et al., 2014). We believe that the same strategy can be applied to soybean in the near future. These new functional genomics approaches and genome editing tools will greatly facilitate the cloning of SMV resistant genes and elucidating the SMV resistant signaling pathways. Marker assisted selection (MAS) has become very useful in the effort of tagging genes for SMV resistance. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is a powerful tool in genome mapping, association studies, and cloning of important genes (Clevenger et al., 2015) and the increasingly saturated SNPs are being established in soybean (Wu et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2015). With all these tools and resources available, pyramiding multiple SMV resistance genes in elite soybean cultivars to generate durable resistance with broad spectrum is more realistic than ever.

Author Contributions

J-ZL wrote most part of this manuscript and prepared the figure and tables. YF and HP helped to write part of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We regret that we were unable to cite all the references in the field due to space limitations. We thank Ray Liu for proofreading and editing this manuscript.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571423 and 31371401 to J-ZL), Qianjiang Talent Program of Zhejiang Province (2013R10074 to J-ZL) and Xin Miao Program of Zhejiang Province.

References

- Belkhadir Y., Subramaniam R., Dangl J. L. (2004). Plant disease resistance protein signaling: NBS-LRR proteins and their partners. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7 391–399. 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard R. L., Nelson R. I., Cremeens C. R. (1991). USDA soybean genetic collection: isoline collection. Soybean Genet. Newsl. 18 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Arsovski A. A., Yu K., Wang A. (2016a). Deep sequencing leads to the identification of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5a as a key element in Rsv1-mediated lethal systemic hypersensitive response to Soybean mosaic virus infection in Soybean. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10.1111/mpp.12407 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Arsovski A. A., Yu K., Wang A. (2016b). Genome-wide investigation using sRNA-Seq, degradome-Seq and transcriptome-Seq reveals regulatory networks of microRNAs and their target genes in soybean during Soybean mosaic virus Infection. PLoS ONE 11:e0150582 10.1371/Journal.pone.0150582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang L., Yu K., Wang A. (2015). Pathogenesis of Soybean mosaic virus in soybean carrying Rsv1 gene is associated with miRNA and siRNA pathways, and breakdown of AGO1 homeostasis. Virology 476 395–404. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Buss G. R., Roane C. W., Tolin S. A. (1991). Allelism among genes for resistance to Soybean mosaic virus in strain differential soybean cultivars. Crop Sci. 31 305–309. 10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100020015x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Buss G. R., Tolin S. A. (1993). Resistance to Soybean mosaic virus conferred by two independent dominant genes in PI 486355. Heredity 84 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Ma G., Buss G. R., Gunduz I., Roane C. W., Tolin S. A. (2001). Inheritance and allelism test of Raiden soybean for resistance to Soybean mosaic virus. J. Hered. 92 51–55. 10.1093/jhered/92.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E. K., Goodman R. M. (1979). Strains of Soybean mosaic virus: classification based on virulence in resistant soybean cultivars. Phytopathology 69 467–470. 10.1094/Phyto-69-467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E. K., Goodman R. M. (1982). Evaluation of resistance in soybeans to Soybean mosaic virus strains. Crop Sci. 22 1133–1136. 10.2135/cropsci1982.0011183X002200060012x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B. K., Koo J. M., Ahn H. J., Yum H. J., Choi C. W., Ryu K. H., et al. (2005). Emergence of Rsv-resistance breaking Soybean mosaic virus isolates from Korean soybean cultivars. Virus Res. 112 42–51. 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowda-Reddy R. V., Sun H., Chen H., Poysa V., Ling H., Gijzen M., et al. (2011a). Mutations in the P3 protein of Soybean mosaic virus G2 isolates determine virulence on Rsv4-genotype soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24 37–43. 10.1094/MPMI-07-10-0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowda-Reddy R. V., Sun H., Hill J. H., Poysa V., Wang A. (2011b). Simultaneous mutations in multi-viral proteins are required for Soybean mosaic virus to gain virulence on soybean. (genotypes)carrying different R genes. PLoS ONE 6:e28342 10.1371/journal.pone.0028342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger J., Chavarro C., Pearl S. A., Ozias-Akins P., Jackson S. A. (2015). Single nucleotide polymorphism identification in polyploids: a review, example, and recommendations. Mol. Plant. 8 831–846. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. E., Bayless A. M., Wang K., Guo X., Song Q., Jiang J., et al. (2014). Distinct copy number, coding sequence, and locus methylation patterns underlie Rhg1-mediated soybean resistance to soybean cyst nematode. Plant Physiol. 165 630–647. 10.1104/pp.114.235952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D. E., Lee T. G., Guo X., Melito S., Wang K., Bayless A. M., et al. (2012). Copy number variation of multiple genes at Rhg1 mediates nematode resistance in soybean. Science 338 1206–1209. 10.1126/science.1228746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger A. L., Hajimorad M. R., Hill J. H. (2008). Gain of virulence on Rsv1-genotype soybean by an avirulent Soybean mosaic virus requires concurrent mutations in both P3 and HC-Pro. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21 931–936. 10.1094/MPMI-21-7-0931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger A. L., Stark D. M., Beachy R. N. (1989). The nucleotide sequence of a Soybean mosaic virus coat protein-coding region and its expression in Escherichia coli, Agrobacterium tumefaciens and tobacco callus. J. Gen. Virol. 70 1853–1860. 10.1099/0022-1317-70-7-1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D., Ghabrial S. A., Kachroo A. (2009). GmRAR1 and GmSGT1 are required for basal, R gene–mediated and systemic acquired resistance in soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22 86–95. 10.1094/MPMI-22-1-0086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Zhan Y., Zhi H., Gai J., Yu D. (2006). Mapping of SMV resistance gene Rsc-7 by SSR markers in soybean. Genetica 128 63–69. 10.1007/s10709-005-5535-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagarinova A. G., Babu M. R., Poysa V., Hill J. H., Wang A. (2008). Identification and molecular characterization of two naturally occurring Soybean mosaic virus isolates that are closely related but differ in their ability to overcome Rsv4 resistance. Virus Res. 138 50–56. 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Ding X., Li K., Liao W., Zhong Y., Ren R., et al. (2015). Characterization of Soybean mosaic virus resistance derived from inverted repeat-SMV-HC-Pro genes in multiple soybean cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128 1489–1505. 10.1007/s00122-015-2522-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore M. A., Hayes A. J., Jeong S. C., Yue Y. G., Buss G. R., Maroof S. (2002). Mapping tightly linked genes controlling potyvirus infection at the Rsv1 and Rpv1 region in soybean. Genome 45 592–599. 10.1139/g02-009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz I., Buss G. R., Ma G., Chen P., Tolin S. A. (2000). Genetic analysis of resistance to Soybean mosaic virus in OX670 and Haro-soy soybean. Crop Sci. 41 1785–1791. 10.2135/cropsci2001.1785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz I., Buss G. R., Chen P., Tolin S. A. (2002). Characterization of SMV resistance genes in Tousan 140 and Hourei soybean. Crop Sci. 42 90–95. 10.2135/cropsci2002.0090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D. Q., Zhi H. J., Wang Y. W., Gai J. Y., Zhou X. A., Yang C. L. (2005). Identification and distribution of strains of Soybean mosaic virus in middle and northern of Huang Huai Region of China. Soybean Sci. 27 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hajimorad M. R., Eggenberger A. L., Hill J. H. (2003). Evolution of Soybean mosaic virus-G7 molecularly cloned genome in Rsv1-genotype soybean results in emergence of a mutant capable of evading Rsv1- mediated recognition. Virology 314 497–509. 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00456-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajimorad M. R., Eggenberger A. L., Hill J. H. (2005). Loss and gain of elicitor function of Soybean mosaic virus G7 provoking Rsv1-mediated lethal systemic hypersensitive response maps to P3. J. Virol. 79 1215–1222. 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1215-1222.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajimorad M. R., Eggenberger A. L., Hill J. H. (2006). Strain-specific P3 of Soybean mosaic virus elicits Rsv1-mediated extreme resistance, but absence of P3 elicitor function alone is insufficient for virulence on Rsv1-genotype soybean. Virology 345 156–166. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajimorad M. R., Eggenberger A. L., Hill J. H. (2008). Adaptation of Soybean mosaic virus avirulent chimeras containing P3 sequences from virulent strains to Rsv1-genotype soybeans is mediated by mutations in HC-Pro. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21 937–946. 10.1094/MPMI-21-7-0937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajimorad M. R., Hill J. H. (2001). Rsv1-mediated resistance against Soybean mosaic virus-N is hypersensitive response-independent at inoculation site, but has the potential to initiate a hypersensitive response-like mechanism. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 14 587–598. 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.5.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. J., Jeong S. C., Gore M. A., Yu Y. G., Buss G. R., Tolin S. A., et al. (2004). Recombination within a nucleotide-bindingsite/leucine-rich-repeat gene cluster produces new variants conditioning resistance to Soybean mosaic virus in soybeans. Genetics 166 493–503. 10.1534/genetics.166.1.493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. J., Ma G., Buss G. R., Saghai Maroof M. A. (2000). Molecular marker mapping of Rsv4, a gene conferring resistance to all known strains of Soybean mosaic virus. Crop Sci. 40 1434–1437. 10.2135/cropsci2000.4051434x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. H., Whitham S. A. (2014). Control of virus diseases in soybeans. Adv. Virus Res. 90 355–390. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801246-8.00007-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T. Y., Moon J. K., Yu S., Yang K., Mohankumar S., Yu Y. H., et al. (2006). Application of comparative genomics in developing molecular markers tightly linked to the virus resistance gene Rsv4 in soybean. Genome 49 380–388. 10.1139/G05-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilut D. C., Lipka A. E., Jeong N., Bae D. N., Kim D. H., Kim J. H., et al. (2016). Identification of haplotypes at the Rsv4 genomic region in soybean associated with durable resistance to Soybean mosaic virus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129 453–468. 10.1007/s00122-015-2640-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram C. H., Hill J. H., Miller W. A. (1992). Complete nucleotide sequences of two Soybean mosaic virus strains differentiated by response of soybean containing the Rsv resistance gene. J. Gen. Virol. 73 2067–2077. 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. C., Hayes A. J., Biyashev R. M., Saghai Maroof M. A. (2001). Diversity and evolution of a non-TIR-NBS sequence family that clusters to a chromosomal “hotspot” for disease resistance genes in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103 406–414. 10.1007/s001220100567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. C., Kristipati S., Hayes A. J., Maughan P. J., Noffsinger S. L., Gunduz I., et al. (2002). Genetic and sequence analysis of markers tightly linked to the Soybean mosaic virus resistance gene Rsv3. Crop Sci. 42 265–270. 10.2135/cropsci2002.0265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatabi B., Fajolu O. L., Wen R. H., Hajimorad M. R. (2012). Evaluation of North American isolates of Soybean mosaic virus for gain of virulence on Rsv-genotype soybeans with special emphasis on resistance-breaking determinants on Rsv4. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13 1077–1088. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00817.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatabi B., Wen R. H., Hajimorad M. R. (2013). Fitness penalty in susceptible host is associated with virulence of Soybean mosaic virus on Rsv1-genotype soybean: a consequence of perturbation of HC-Pro and not P3. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14 885–897. 10.1111/mpp.12054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiihl R. A. S., Hartwig E. E. (1979). Inheritance of reaction to Soybean mosaic virus in soybeans. Crop Sci. 19 372–375. 10.2135/cropsci1979.0011183X001900030024x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-G., Jeong N., Kim J. H., Lee K., Kim K. H., Pirani A., et al. (2015). Development, validation and genetic analysis of a large soybean SNP genotyping array. Plant J. 81 625–636. 10.1111/tpj.12755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Yang Q. H., Zhi H. J., Gai J. Y., Yu D. Y. (2010). Identification and distribution of Soybean mosaic virus strains in southern China. Plant Dis. 94 351–357. 10.1094/PDIS-94-3-0351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Z., Braun E., Qiu W.-L., Marcelino-Guimarães F. C., Navarre D., Hill J. H., et al. (2014). Positive, and negative roles for soybean MPK6 in regulating defense responses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28 824–834. 10.1094/MPMI-11-13-0350-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Z., Graham M. A., Pedley K. F., Whitham S. A. (2015). Gaining insight into soybean defense responses using functional genomics approaches. Brief. Funct. Genomics 14 283–290. 10.1093/bfgp/elv009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Z., Horstman H. D., Braun E., Graham M. A., Zhang C., Navarre D., et al. (2011). Soybean homologs of MPK4 negatively regulate defense responses and positively regulate growth and development. Plant Physiol. 157 1363–1378. 10.1104/pp.111.185686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-Z., Whitham S. A. (2013). Over-expression of a nuclear-localized DnaJ domain-containing HSP40 from soybean reveals its roles in cell death and disease resistance. Plant J. 74 110–121. 10.1111/tpj.12108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan H., Shine M. B., Cui X., Chen X., Ma N., Kachroo P., et al. (2016). The potyviral P3 protein targets eukaryotic elongation factor 1A to promote the unfolded protein response and viral pathogenesis. Plant Physiol. 172 221–234. 10.1104/pp.16.00505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G., Chen P., Buss G. R., Tolin S. A. (1995). Genetic characteristics of two genes for resistance to Soybean mosaic virus in PI486355 soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 91 907–914. 10.1007/BF00223899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G., Chen P., Buss G. R., Tolin S. A. (2002). Complementary action of two independent dominant genes in Columbia soybean for resistance to Soybean mosaic virus. J. Hered. 93 179–184. 10.1093/jhered/93.3.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Zhang S. (2013). MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51 245–266. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñuela D., Danesh D., Young N. D. (2002). Targeted isolation, sequence analysis, and physical mapping of nonTIR NBS-LRR genes in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 104 261–272. 10.1007/s00122-001-0785-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M., Brodersen P., Naested H., Andreasson E., Lindhart U., Johansen B., et al. (2000). Arabidopsis map kinase 4 negatively regulates systemic acquired resistance. Cell 103 1111–1120. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00213-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghai Maroof M. A., Tucker D. M., Skoneczka J. A., Bowman B. C., Tripathy S., Tolin S. A. (2010). Fine mapping and candidate gene discovery of the Soybean mosaic virus resistance gene, Rsv4. Plant Genome 3 14–22. 10.3835/plantgenome2009.07.0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J., Cannon S. B., Schlueter J., Ma J., Mitros T., Nelson W., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463 178–183. 10.1038/nature08670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J. K., Kwon S. J., Cho W. K., Choi H. S., Kim K. H. (2014). Type 2C protein phosphatase is a key regulator of antiviral extreme resistance limiting virus spread. Sci. Rep. 4:5905 10.1038/srep05905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J. K., Lee S. H., Kim K. H. (2009). Strain-specific cylindrical inclusion protein of Soybean mosaic virus elicits extreme resistance and a lethal systemic hypersensitive response in two resistant soybean cultivars. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22 1151–1159. 10.1094/MPMI-22-9-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J. K., Sohn S. H., Kim K. H. (2011). A single amino acid change in HC-Pro of Soybean mosaic virus alters symptom expression in a soybean cultivar carrying Rsv1 and Rsv3. Arch. Virol. 156 135–141. 10.1007/s00705-010-0829-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi A., Chen P., Li D. X., Zheng C., Hou A., Zhang B. (2008). Genetic confirmation of 2 independent genes for resistance to Soybean mosaic virus in J05soybean using SSR markers. J. Hered. 99 598–603. 10.1093/jhered/esn035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi A., Chen P., Vierling R., Zheng C., Li D., Dong D., et al. (2011). Multiplex single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) assay for detection of Soybean mosaic virus resistance genes in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122 445–457. 10.1007/s00122-010-1459-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh S. J., Bowman B. C., Jeong N., Yang K., Kastl C., Tolin S. A., et al. (2011). The Rsv3 locus conferring resistance to Soybean mosaic virus is associated with a cluster of coiled-coil nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat genes. Plant Genome 4 55–64. 10.3835/plantgenome2010.11.0024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Ma Y., Yang Y., Liu N., Li C., Song Y., et al. (2011). Fine mapping and analyses of R (SC8) resistance candidate genes to Soybean mosaic virus in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122 555–565. 10.1007/s00122-010-1469-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Q., Gai J. Y., Pu Z. Q. (2003). Classification and distribution of strains of Soybean mosaic virus in middle and lower Huanghuai and Changjiang river valleys. Soybean Sci. 22 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Cheng X., Shan Q., Zhang Y., Liu J., Gao C., et al. (2014). Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 947–951. 10.1038/nbt.2969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Hajimorad M. R. (2016). Gain of virulence by Soybean mosaic virus on Rsv4-genotype soybeans is associated with a relative fitness loss in a susceptible host. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17 1154–1159. 10.1111/mpp.12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Khatabi B., Hajimorad M. R. (2015). Amino acid substitution in P3 of Soybean mosaic virus to convert avirulence to virulence on Rsv4-genotype soybean is influenced by the genetic composition of P3. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16 301–307. 10.1111/mpp.12175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. J., Dongfang Y., Wang X. Q., Yang Y. L., Yu D. Y., Gai J. Y., et al. (2004). Mapping of five genes resistant to SMV strains in soybean. Acta Genet. Sin. 31 87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen R.-H., Hajimorad M. R. (2010). Mutational analysis of the putative pipo of soybean mosaic virus suggests disruption of PIPO protein impedes movement. Virology 400 1–7. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen R. H., Khatabi B., Ashfield T., Saghai Maroof M. A., Hajimorad M. R. (2013). The HC-Pro and P3 cistrons of an avirulent Soybean mosaic virus are recognized by different resistance genes at the complex Rsv1 locus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26 203–215. 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0156-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen R. H., Maroof M. A., Hajimorad M. R. (2011). Amino acid changes in P3, and not the overlapping pipo-encoded protein, determine virulence of Soybean mosaic virus on functionally immune Rsv1-genotype soybean. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12 799–807. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00714.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Ren C., Joshi T., Vuong T., Xu D., Nguyen H. T. (2010). SNP discovery by high-throughput sequencing in soybean. BMC Genomics 11:469 10.1186/1471-2164-11-469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Wang H., Cheng H., Hu Z., Chu S., Zhang G., et al. (2015). Detection and fine-mapping of SC7 resistance genes via linkage and association analysis in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57 722–729. 10.1111/jipb.12323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. H., Gai J. Y. (2011). Identification, inheritance and gene mapping of resistance to a virulent Soybean mosaic virus strain SC15 in soybean. Plant Breed. 130 128–132. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2010.01797.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zheng G., Han L., Dagang W., Yang X., Yuan Y., et al. (2013). Genetic analysis and mapping of genes for resistance to multiple strains of Soybean mosaic virus in a single resistant soybean accession PI 96983. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126 1783–1791. 10.1007/s00122-013-2092-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X., Wang J., Cheng H., Wang X., Yu D. (2013). Detection and evolutionary analysis of soybean miRNAs responsive to Soybean mosaic virus. Planta 237 1213–1225. 10.1007/s00425-012-1835-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. G., Saghai Maroof M. A., Buss G. R. (1996). Divergence and allele-morphic relationship of a soybean virus resistance gene based on tightly linked DNA microsatellite and RFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 92 64–69. 10.1007/BF00222952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. G., Saghai-Maroof M. A., Buss G. R., Maughan P. J., Tolin S. A. (1994). RFLP and microsatellite mapping of a gene for Soybean mosaic virus resistance. Phytopathology 84 60–64. 10.1094/Phyto-84-60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Bradshaw J. D., Whitham S. A., Hill J. H. (2010). The development of an efficient multi-purpose BPMV viral vector for foreign gene expression and RNA silencing. Plant Physiol. 153 1–14. 10.1104/pp.109.151639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Grosic S., Whitham S. A., Hill J. H. (2012). The requirement of multiple defense genes in soybean Rsv1–mediated extreme resistance to Soybean mosaic virus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25 1307–1313. 10.1094/MPMI-02-12-0046-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Hajimorad M. R., Eggenberger A. L., Tsang S., Whitham S. A., Hill J. H. (2009a). Cytoplasmic inclusion cistron of Soybean mosaic virus serves as a virulence determinant on Rsv3-genotype soybean and a symptom determinant. Virology 391 240–248. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Yang C., Whitham S. A., Hill J. H. (2009b). Development and use of an efficient DNA-based viral gene silencing vector for soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22 123–131. 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Sato S., Ye X., Dorrance A. E., Morris T. J., Clemente T. E., et al. (2011). Robust RNAi-based resistance to mixed infection of three viruses in soybean plants expressing separate short hairpins from a single transgene. Phytopathology 101 1264–1269. 10.1094/PHYTO-02-11-0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C., Chen P., Gergerich R. (2006). Genetic analysis of resistance to Soybean mosaic virus in j05 soybean. J. Hered. 97 429–437. 10.1093/jhered/esl024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., He H., Liu R., Han Q., Shou H., Liu B. (2014). Overexpression of GmAKT2 potassium channel enhances resistance to Soybean mosaic virus. BMC Plant Biol. 14:154 10.1186/1471-2229-14-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., He H., Ma L., Yu X., Mi Q., Pang J., et al. (2015). Overexpression of a GmCnx1 gene enhanced activity of nitrate reductase and aldehyde oxidase, and boosted mosaic virus resistance in soybean. PLoS ONE 10:e0124273 10.1371/journal.pone.0124273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]