Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this commentary is to provide an argument for the role and identity of chiropractors as spine care providers within the context of the greater health care system.

Discussion

Surveys of the general public and chiropractors indicate that the majority of patients seek chiropractic services for back and neck pain. Insurance company utilization data confirm these findings. Regulatory and legal language found in chiropractic practice acts reveals that most jurisdictions define the chiropractic scope of practice as based on a foundation of spine care. Educational accrediting and testing organizations have been shaped around a chiropractic education that produces graduates who focus on the diagnosis and treatment of spine and musculoskeletal disorders. Spine care is thus the common denominator and theme throughout all aspects of chiropractic practice, legislation, and education globally.

Conclusion

Although the chiropractic profession may debate internally about its professional identity, the chiropractic identity seems to have already been established by society, practice, legislation, and education as a profession of health care providers whose area of expertise is spine care.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, Spine

Introduction

Chiropractors are still—after 120 years—debating their professional identity. In the meantime, with an increasing awareness of the impact of spinal pain and disability in societies all over the world, other professions are starting to target evidence-based spine care as a focus for their professional identity.

A successful profession is formed in response to a societal need.1 The purpose, and thus the identity of a profession is therefore, to a large extent, determined by how members of the public choose to use that profession’s services.

An identity is composed of the qualities that make a particular person or group different from others.2 Every successful profession has an identity, which is shaped and developed by the specialized knowledge, skills, training, and innovation of the individuals within that group. This is especially true of health care professions; which patients associate certain types of health care clinicians with certain types of conditions. In most Western societies, people are raised in a culture that identifies primary care physicians (PCPs) and their extenders (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) as the first-contact health care provider who diagnoses health problems. Once a diagnosis has been made and a specific condition has been identified, PCPs have 2 possible choices1: manage or treat the condition themselves, or2 refer the patient to another health care provider who has more specialized knowledge of that particular condition.

Essentially, health care professionals can be divided into 2 broad categories: generalists and specialists. Providers in the generalist category must have solid knowledge of a broad range of conditions, whereas specialists have more concentrated and deeper knowledge of a narrower range of conditions. Patients automatically identify a health care provider as either a generalist or specialist based on the type of health care conditions that the provider has the knowledge, skills, and training to diagnose and treat. Patients tend to gravitate toward specialists for care of more complicated health care conditions or for conditions that are not responding well to care by a generalist. In this environment, does a profession then have the ability to choose its identity and project it onto society, or does society choose an identity and project in onto the profession? For the chiropractic profession, this leads to an important question in its debate on professional identity: How are chiropractors perceived by patients and other health care providers—as generalists or as specialists? Also, in the emerging interprofessional team-based approach to health care, what role is there for the chiropractor? We suggest the following answers to these questions1: chiropractors are perceived as specialists who provide nonsurgical, nonpharmacologic spine care2; society confers cultural authority and identities onto professions, not the other way around; and3 chiropractors possess the specialized knowledge, skills, and training to provide care for patients with spine-related disorders.

We propose that there are 3 fundamental errors that the chiropractic profession has made with respect to establishing and promoting its professional identity. The first error is thinking that it is possible for a profession to choose an identity. Society confers an identity onto a profession, not the other way around. Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “Who you are speaks so loudly that I cannot hear what you are saying.” He describes people or groups whose credibility is eroded because of opinions, philosophies, or past actions, and it is quite applicable to the debate over chiropractic identity.3 Regardless of how loudly the chiropractic profession speaks about multiple and conflicting identities, the general public, legislative/regulatory bodies, and chiropractic organizations appear to have already established a default identity for the chiropractic profession; namely, as back and neck pain doctors.

The second error is thinking that through advertising, marketing, or “patient education,” it possible to change the public’s perception of chiropractic. Over the years, there have been various attempts to influence public opinion toward different chiropractic identities, and these have simply not worked. For example, in 1996, the Ontario Chiropractic Association developed and tested market branding of chiropractic for the purposes of public education.4 The idea was to run television advertisements with the message that most people suffer from “subluxations,” which, if left untreated, would lead to health problems and that chiropractors were the only doctors who specialize in the treatment of “subluxations.” A series of ads were run in an effort to generate increased awareness and understanding of chiropractic, particularly among those who have never received chiropractic treatment. Marketing consultants conducted phone interviews with 250 members of the general public before and after these commercials were aired to gather information on the effect of the advertising campaign on shifting the public’s perception of chiropractic. They found that rather than improving the public’s perception of chiropractic, their marketing campaign had the opposite effect. The authors who presented the qualitative interview data concluded that: “Television is a strong medium for chiropractic advertising. While the term subluxation is well recalled, this research does suggest that knowing about subluxation does not meaningfully increase interest in chiropractic. In fact, the lower chiropractic attitudinal ratings suggest some deterioration in attitudes. In a nutshell, subluxation does not appear to be the power idea that will attract new patients. The term subluxation may get some attention and it may be uniquely associated with chiropractic, but it does not appear to be persuasive or compelling enough to move people to seek treatment from a chiropractor.”4 Therefore, advertising is not able to fundamentally change the public’s perception of chiropractic.

The third error is trying to brand chiropractors as clinical “jacks of all trades” with a broad knowledge about a large number of health care conditions. For several years, the Foundation for Chiropractic Progress, a not-for-profit organization, has provided information in the form of press releases, advertisements, and a website aimed toward educating the public about chiropractic care. The Foundation for Chiropractic Progress messages lack a consistent identity message for the chiropractic profession.5 For example, one advertisement features a professional athlete with a message about “staying in the game” with chiropractic, whereas the next advertisement features a retired army general with the headline “be all you can be with chiropractic.” These conflicting messages confuse the public and do not clarify who chiropractors are and what they do. For example, it has not been established how chiropractic care helps people “stay in the game” or “be all they can be”; thus, the messages are unclear. The messages are also inconsistent: What does “staying in the game” have to do with “being all you can be”? Further, the messages are incomplete in that they include no research evidence to support a clear societal need for chiropractic care and its unique role in the health care system. Promoting the notion that chiropractors provide so many different types of health care services confuses, rather than clarifies, public perceptions about chiropractic identity.

Chiropractors have tried to position themselves in the public eye as a wide variety of specialists: as experts in spine care, pediatric care, wellness, sports medicine, nutrition, herbal remedies, and subluxation correction as well as alternative PCPs.

When patients have a pain of unknown origin, they typically see a PCP or general practitioner to determine what is wrong. If, after they have received the diagnosis, the condition does not improve, they prefer to see a health care provider who specializes in that condition; they do not want to see a jack of all trades.6 Patients are dissatisfied with the way PCPs and general practitioners manage their back pain, and general practitioners do not like to see back pain patients.7 Qualitative research has revealed that patients are often dissatisfied with treatment for back pain from their general practitioners for specific reasons.8 They expect their doctor to confirm that their pain is real, conduct a physical examination, and state a clear diagnosis about the cause of their pain. They also want pain relief and information about what they can do to help themselves.8

Patients with spine pain may seek out chiropractic care because they perceive chiropractors to be specialists in spine care who meet their expectations regarding treatment for back pain. Chiropractors should embrace the public perception of the profession as specialists in spine care and focus public relations efforts on bolstering the existing spine care identity of chiropractic. This approach would be the path of least resistance toward establishing a niche for chiropractors in the health care system and would align with the current public perception of chiropractors as “back and neck doctors.”

The purpose of this commentary is to argue that chiropractors should embrace the identity of providers of care for patients with spine-related disorders using a summary of the evidence for the chiropractic spine care identity as found in society, legislation, practice, and education.

Discussion

The General Public

Surveys from Sweden,9 Denmark,10, 11 Holland,12 the United Kingdom,13 and the United States14, 15, 16, 17 have consistently indicated that the majority of patients seek chiropractic care because of back and neck pain. The authors of a Danish study compared the current profile of patients seeking care from chiropractors with the profile of those seeking care 40 years ago and concluded that the profile has not changed since the early 1960s.18

The National Board of Chiropractic Examiners (NBCE) has conducted job analysis surveys of chiropractors in the United States every 5 years for the past 20 years.14, 15, 16, 17 Chiropractors have consistently reported in these surveys that more than 70% of new patients are seen for a chief complaint of back or neck pain. Even for chiropractors who perceived themselves as providing care for a broad range of health conditions including nonmusculoskeletal complaints, the majority of patients who sought chiropractic care reported the reason is primarily musculoskeletal and particularly spinal complaints.18 The vast majority of patients in chiropractors’ offices are there for a chief complaint of either back or neck pain. Therefore, the general public views chiropractors as specialists in spine care.

There is evidence from insurance claims data that patients view chiropractors as health care providers for back and neck pain. Claims data from United Health Care, the largest insurance company in the United States, reveal that 40% of patients with an acute episode of low back pain choose to see a chiropractor as their first contact provider.19 Compare this with the 38% of patients who choose to see PCPs and the less than 8% who choose to see a physical therapist. In Denmark, every third patient seeking care for back pain chooses a chiropractor as their first point of contact.20 In a recent survey, Australian women with back pain were asked what type of health care provider they chose for their back pain. About half of the women consulted a general practitioner (MD) as their first contact provider; another 20% viewed a chiropractor as their portal-of-entry provider.21 Although some chiropractors complain that only a small number of people use chiropractic services, these data suggest otherwise. Patients with low back pain chose to see a chiropractor as their first contact provider in numbers that almost equaled those who chose to see a PCP as their first contact provider.19 These data provide compelling evidence that the general public views the chiropractor as the “go to” health care provider for low back pain and also support a spine care identity for the chiropractic profession.

Legislative and Regulatory Bodies

Legislative acts around the world have shaped chiropractic’s identity of focus on spine and musculoskeletal disorders.22 These practice acts contain language that identifies chiropractors as health care professionals concerned mostly with the spine, nervous system, and general health.23 Although some chiropractors would like the general public to consider them alternative PCPs,24 several states in the United States prohibit use of the term chiropractic physician. The scope of practice may be broad in some states, whereas in other states, chiropractors are limited to the examination and treatment of the spine and its contiguous joints. A common denominator across these legislative practice acts globally is scope-of-practice language that shapes the identity of chiropractors as clinicians who provide spine care.

A published review of the chiropractic practice laws in the United States revealed wide variation in scope-of-practice language between states, but some common themes also emerged from this review.25 All states consider chiropractors to be first-contact or portal-of-entry providers, but they also all have regulatory prohibitions that place boundaries on chiropractors’ scope of practice and clinical authority. With very few exceptions, it would be not be possible in most states for a chiropractor to act in the role of a PCP. In many states, chiropractors are prohibited from referring to themselves as physicians and, in many cases, are restricted to providing treatment of the spine and extremities.

All 50 states in the United States have adopted uniform accreditation requirements for Doctor of Chiropractic training programs, which require licensees to have graduated from a program that was accredited by the Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE). In addition, all states have adopted uniform competency requirements, which require licensees to have successfully completed the 4-part series of examinations administered by the NBCE. Therefore, the CCE and NBCE competency requirements provide for spine and musculoskeletal care as the foundation of chiropractic clinical practice.

Chiropractic Organizations and Education

At the World Federation of Chiropractic’s 8th Biennial Congress held in Sydney, Australia, in 2005, there was consensus on the public identity of the chiropractic profession within all health care systems worldwide: “the spinal health care experts in the health care system.”26 As well, the Institute of Alternative Futures was commissioned by chiropractic organizations to produce 3 independent analyses and reports of the chiropractic profession in 1998, 2005, and 2013.27, 28, 29 These analyses came to the conclusion that chiropractors are seen by the public chiefly as experts in spine care.

A chiropractic identity position statement focused on the spine is being actively promoted by Palmer College of Chiropractic, the foundation and birthplace of the chiropractic profession. Palmer recently developed the following chiropractic identity statement: “the primary care professional for spinal health and well-being.”30 It blends well the concepts of a focus on spine care with a holistic view of patients’ overall well-being. The common theme that emerges from these chiropractic organizations, surveys, and consensus conferences on the chiropractic identity is spine care. All chiropractors, regardless of their other interests and skills, are knowledgeable about the clinical management of spinal and musculoskeletal disorders.

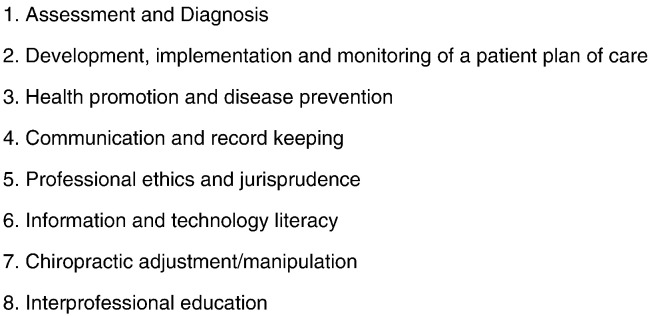

Chiropractic education and licensing standards are also heavily focused on the diagnosis and treatment of spine and musculoskeletal disorders. The CCE accredits chiropractic educational programs in the United States. In addition to CCE requirements, chiropractic educational programs in some countries are subject to their respective national accreditation bodies. The CCE accreditation standards require that all graduates of chiropractic programs demonstrate a number of meta-competencies.31 These meta-competencies collectively provide a structure for the education of a health care professional who will be exhibiting clinical competency primarily in managing spine and musculoskeletal disorders, in the context of health promotion and disease prevention (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Eight meta-competencies required of all graduates of Council on Chiropractic Education-Accredited Doctor of Chiropractic programs.

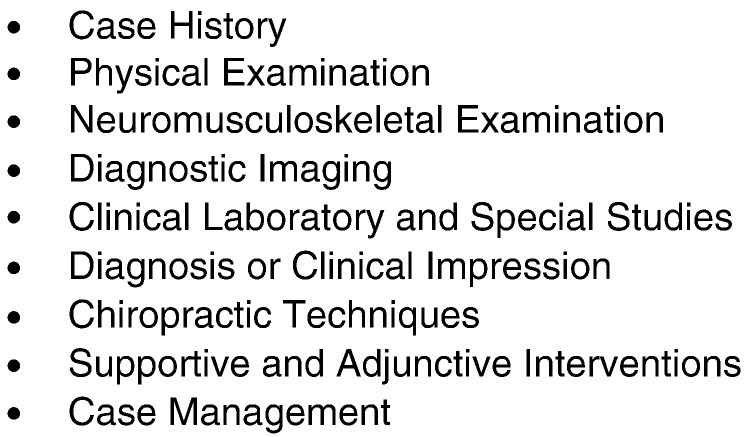

The NBCE assesses chiropractic graduates on clinical abilities and competencies in the United States.32 Many countries have similar systems of ensuring competencies in new chiropractic graduates. Collectively, these competency examinations are focused on the differential diagnosis and clinical management of spine and musculoskeletal disorders (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Clinical competencies that constitute the part 3 examination offered by the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners.

Doctors of Chiropractic as Back and Neck Pain Doctors: Untapped Potential

Back and neck pain is recognized as the leading cause of disability globally.33 Disability from back pain has increased more than 50% since 1990, and there is general concern that health care systems are contributing to, rather than reducing, this burden.34 The current health care environment for spine care is chaotic, costly, and, in many parts of the world, of little benefit to patients.35 Despite the lack of evidence of benefit, there has been an increased emphasis in recent years on invasive, expensive, and specialist-focused approaches, with diminishing returns in terms of patient outcome.36, 37, 38 As health care systems around the world continue to move toward a value model,39 there is increasing recognition of the need for more effective, less invasive, and less expensive approaches to spine care. A profession that can effectively respond to this need will be highly valued in society. Therein lies a tremendous opportunity for the chiropractic profession.

In response to the need for high-quality, inexpensive spine care, there is a growing movement toward implementing primary spine care services within the health care system, with the designation of a new practitioner type to serve as the focus of this service line, the primary spine practitioner.40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Although no profession, in its entirety, currently possesses all of the knowledge, skills, and training required to serve as an ideal primary spine practitioner, the chiropractic profession is clearly the closest. By embracing a clear identity as a spine care provider, the chiropractic profession may position itself to capitalize on this movement by making the necessary changes that allow it to produce practitioners that are prepared to take on this role.

Although chiropractic education and training are focused on the spine and musculoskeletal system, there are few residencies or interprofessional clinical training opportunities. To completely fill the role as primary spine practitioners, most chiropractors will need some additional training. This will require a continued educational focus on spine care and expansion of training in modern, evidence-based diagnostic and management strategies, self-care strategies, identification and management of psychological perpetuating factors, case coordination, referral and follow-up decisions, interaction with other providers who are involved in spine care, leading the interdisciplinary management of difficult and complicated cases, as well as professional involvement in public health approaches to prevention of spine pain and its related disability.46, 47, 48

Public health approaches could include the promotion of physical activity and education regarding rational beliefs and behavior when the inevitable back and/or neck pain episodes arise.49, 50, 51, 52 An emphasis on patient education, self-management, and decreased reliance on treatments and health care professionals could be emphasized. The first step in establishing chiropractic as a contributor to public health would be for the chiropractic profession to establish a clear identity around spine care.

The chiropractic profession needs to take on leading roles in patient-centered education and research. This could help establish in the minds of the public and those in the health care community that doctors of chiropractic are experts in spine care. In this case, we define experts as people with superior education who drive research and development in a particular area, not simply those who claim authority and expertise.

Spine Care Is Whole-Person Care

Some chiropractors are not comfortable with a spine care identity. The argument is that they feel it limits their scope of practice. We believe this is a flawed argument for the following reasons. First, a focused identity as a spine care expert is highly relevant and needed, because almost all human beings experience back or neck pain at some point in life.53 Second, spine pain care is whole-person care because pain and disability in the spine are associated with many physical and psychological perpetuating factors and comorbidities.54 Thus, a focus on the spine naturally involves a holistic approach to health care because spine problems are part of biopsychosocial phenomena. That is, the whole person is involved—body, mind, and spirit. By establishing an identity as spine doctors, the chiropractic profession has a wonderful opportunity to bring its traditional “whole-person” mindset to an unprecedented level.55 There is a potential to improve quality of life through reduction of spinal pain and improvement of function. Professionals who are able to engage the public in rational behavior when they are faced with inevitable episodes of spinal pain and who can help patients overcome these episodes may provide an important service for society.56

Having a professional focus on the spine does not mean that chiropractors have to limit themselves only to the spine. It is natural for patients who have had a positive experience with chiropractic care for a spine problem to seek out the same practitioner when they develop a problem in another area of the musculoskeletal system. There is in fact good evidence that chiropractors can be helpful in managing headaches,57, 58 musculoskeletal chest pain,59, 60, 61 osteoarthritis of the hip,62 and a range of other musculoskeletal conditions.63

Limitations

This article is a commentary that represents the collective opinions of the authors. We acknowledge that the idea of one unifying chiropractic identity remains a matter of debate and that there exists disagreement with our opinion that the unifying identity should be spine care. There are many specialized certificate and diplomate programs that offer advanced training to chiropractors in the fields of pediatrics, nutrition and internal disorders, radiology, sports chiropractic, and rehabilitation. Chiropractors who have advanced knowledge, skills, and training may position themselves as being specialty trained and as having a view of identity different from ours. It is also important to point out that other health care professions also may have the knowledge, skills, and training to provide comprehensive spine care, especially physical therapists with advanced training in manual therapy and orthopedics, as well as physical medicine/rehabilitation physicians and osteopathic physicians.

Conclusion

We suggest that the chiropractic profession stop the internal bickering about its identity. It is destructive and demotivating for chiropractors and chiropractic students. We suggest that chiropractors globally accept the identity they already have in the public eye, namely, health care professionals who provide care for people with spine-related disorders. Chiropractors are viewed by the general public as specialists for spine and musculoskeletal care, not generalists or alternative PCPs. When the profession markets itself as having multiple personalities or identities, it confuses people outside of the profession.

We have provided compelling evidence for a spine care identity from surveys of the general public and chiropractors, analyses of insurance claims, legislative scopes of practice, and chiropractic educational standards. Spine care is the common thread that unites all chiropractors, and should serve as the basis of a unified chiropractic identity as specialists in spine care.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): M.S., D.M.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): M.S., D.M.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): M.S., D.M., J.H.

Literature search (performed the literature search): M.S., D.M.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): M.S., D.M., J.H.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): M.S., D.M., J.H.

Practical Applications

-

•

The majority of patients worldwide see chiropractors for back and neck pain.

-

•

Most chiropractic organizations and legislative acts around the world define chiropractors as practitioners of spine care.

-

•

There is a global need for evidence-based spine care providers.

Alt-text: Image 1

References

- 1.Hughes E.C. Professions. Daedalus. 1962;92(4):655–668. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merriam-Webster; Springfield, MA: 2016. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary. New edition. [Google Scholar]

- 3.BrainyQuote Ralph Waldo Emerson quotes. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/r/ralphwaldo103408.html Available at: Accessed September 6, 2016.

- 4.Mizel D., Gorchynski S., Keenan D., Duncan H.J., Gadd M. May 2001. Branding chiropractic for public education: principles and experience from Ontario. Poster presentation at World Federation of Chiropractic Congress. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foundation for Chiropractic Progress. http://www.yes2chiropractic.org/ Available at. Accessed September 6, 2016.

- 6.Porter M.E., Teisberg E.O. Harvard Business School Press; Brighton, MA: 2006. Redefining Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breen A., Austin H., Campion-Smith C., Carr E., Mann E. You feel so hopeless: a qualitative study of GP management of acute back pain. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeek J., Sengers M.J., Riemens L., Haafkens J. Patient expectations of treatment for back pain: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Spine. 2004;29(20):2309–2318. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142007.38256.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leboeuf-Yde C., Hennius B., Rudberg E., Leufvenmark P., Thunman M. Chiropractic in Sweden: a short description of patients and treatment. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20(8):507–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myburgh C., Hartvigsen J., Grunnet-Nilsson N. Secondary legitimacy: a key mainstream health care inclusion strategy for the Danish chiropractic profession? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(5):392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartvigsen J., Sorensen L.P., Graesborg K., Grunnet-Nilsson N. Chiropractic patients in Denmark: a short description of basic characteristics. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(3):162–167. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2002.122325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein S., Pfeifle C.E., van Tulder M.W., Assendelft W.J. Chiropractic patients in the Netherlands: a descriptive study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(8):557–563. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2000.109675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollentier A., Langworthy J.M. The scope of chiropractic practice: a survey of chiropractors in the UK. Clin Chiropr. 2007;10(3):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen M.G., Kerkhoff D., Kollash M. Greeley, CO; National Board of Chiropractic Examiners: 2000. Job Analysis of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christensen M.G., Kollash M., Ward R., Webb K., Day M., zum Brunnen J. Greeley, CO; National Board of Chiropractic Examiners: 2005. Job Analysis of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen M.G., Kollash M., Hyland J. Greeley, CO; National Board of Chiropractic Examiners: 2010. Job Analysis of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen M.G., Hyland J., Goertz C., Kollash M. Greeley, CO; National Board of Chiropractic Examiners: 2015. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartvigsen J., Bolding-Jensen O., Hviid H., Grunnet-Nilsson N. Danish chiropractic patients then and now—a comparison between 1962 and 1999. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26(2):65–69. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2003.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosloff T.M., Elton D., Shulman S., Clarke J., Skoufalos A., Solis A. Conservative spine care: opportunities to improve the quality and value of care. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(6):390–396. doi: 10.1089/pop.2012.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lonnberg F. [The management of back problems among the population: I. Contact patterns and therapeutic routines][in Danish] Ugeskrift for laeger. 1997;159(15):2207–2214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sibbritt D., Lauche R., Sundberg T. Severity of back pain may influence choice and order of practitioner consultations across conventional, allied and complementary health care: a cross-sectional study of 1851 mid-age Australian women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):393. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1251-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawk C., Long C.R., Boulanger K.T. Prevalence of nonmusculoskeletal complaints in chiropractic practice: reports from a practice-based research program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(3):157–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duenas R. United States Chiropractic Practice Acts and Institute of Medicine defined primary care practice. J Chiropr Med. 2002;1(4):155–170. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang M. The chiropractic scope of practice in the United States: a cross-sectional survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(6):363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith M., Carber L. Survey of US chiropractors' perceptions about their clinical role as specialist or generalist. J Chiropr Humanit. 2009;16(1):21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WFC Final Report of the Identity Consultation Task Force https://www.wfc.org/website/images/wfc/docs/as_tf_final_rept-Am_04-29-05_001.pdf Available at. Accessed August 28, 2016.

- 27.Institute for Alternative Futures . Author; VA: 1998. The future of chiropractic: optimizing health gains. NCMIC Insurance Group and Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research Alexandria. Available at http://www.altfutures.org/pubs/health/TheFutureofChiropractic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute for Alternative Futures . Author; Alexandria, VA: 2005. The future of chiropractic revisited: 2005-2015. Available at http://www.altfutures.org/pubs/health/Future%20of%20Chiropractic%20Revisted%20v1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute for Alternative Futures . Author; Alexandria, VA: 2013. Chiropractic 2025: divergent futures. Available at http://www.altfutures.org/pubs/chiropracticfutures/IAF-Chiropractic2025.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer College of Chiropractic Identity statement. http://www.palmer.edu/about-us/identity/#Identity_Statement Available at: Accessed August 28, 2016.

- 31.Council on Chiropractic Education CCE accreditation standards. http://www.cce-usa.org/uploads/2016-08-01_Final_Draft_CCE_Accreditation_Standards_-_Clean_Version.pdf Available at. Accessed August 28, 2016.

- 32.National Board of Chiropractic Examiners Examinations. http://www.nbce.org/examinations/ Available at. Accessed August 28, 2016.

- 33.Vos T., Barber R.M., Bell B. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith E., Hoy D.G., Cross M. The global burden of other musculoskeletal disorders: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1462–1469. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haldeman S., Dagenais S. A supermarket approach to the evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2008;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deyo R.A., Mirza S.K., Turner J.A., Martin B.I. Overtreating chronic back pain: time to back off? J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(1):62–68. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mafi J.N., McCarthy E.P., Davis R.B., Landon B.E. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573–1581. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin B.I., Turner J.A., Mirza S.K., Lee M.J., Comstock B.A., Deyo R.A. Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997-2006. Spine. 2009;34(19):2077–2084. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1fad1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter M.E. A strategy for health care reform-toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):109–112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartvigsen J., Foster N.E., Croft P.R. We need to rethink front line care for back pain. BMJ. 2011;342:d3260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haldeman S. Looking forward. In: Phillips R.B., editor. The Journey of Scott Haldeman: Spine Care Specialist and Researcher. National Chiropractic Mutual Holding Company; Des Moines, IA: 2009. pp. 447–462. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy D.R., Justice B.D., Paskowski I.C., Perle S.M., Schneider M.J. The establishment of a primary spine care practitioner and its benefits to health care reform in the United States. Chiropr Man Therap. 2011;19(1):17. doi: 10.1186/2045-709X-19-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy D.R. Primary spine care services: responding to runaway costs and disappointing outcomes in spine care. RI Med J. 2014;97(10):47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paskowski I., Schneider M., Stevans J., Ventura J.M., Justice B.D. A hospital-based standardized spine care pathway: report of a multidisciplinary, evidence-based process. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34(2):98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allgeier M., Ventura J.M., Murphy D.R. Replication of a multidisciplinary hospital based clinical pathway for the management of low back pain. Spine J. 2016;15(10):117S–118S. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haldeman S. 3rd edition. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2005. Principles and Practices of Chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy D.R. Pawtucket, RI; CRISP Education and Research: 2013. Clinical Reasoning in Spine Pain: Vol. I. Primary Management of Low Back Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy D.R. Pawtucket, RI; CRISP Education and Research: 2016. Clinical Reasoning in Spine Pain: Vol. II. Primary Management of Cervical Disorders and Case Studies in Primary Spine Care. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson C., Rubinstein S.M., Côté P. Chiropractic care and public health: answering difficult questions about safety, care through the lifespan, and community action. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(7):493–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson C., Green B.N. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson C., Baird R., Dougherty P.E. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huber M., Knottnerus J.A., Green L. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoy D., Bain C., Williams G. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–2037. doi: 10.1002/art.34347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy D.R. The etiology of low back disorders—the biopsychosocial model. In: Murphy D.R., editor. Clinical Reasoning in Spine Pain: Vol. I. Primary Management of Low Back Disorders. Pawtucket, RI; CRISP Education and Research: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy D.R., Schneider M.J., Seaman D.R., Perle S.M., Nelson C.F. How can chiropractic become a respected mainstream profession? The example of podiatry. Chiropr Osteopat. 2008;16:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-16-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartvigsen J., Natvig B., Ferreira M. Is it all about a pain in the back? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27(5):613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hurwitz E.L., Vassilaki M., Li D. Variations in patterns of utilization and charges for the care of headache in North Carolina, 2000-2009: a statewide claims' data analysis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(4):229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bryans R., Descarreaux M., Duranleau M. Evidence-based guidelines for the chiropractic treatment of adults with headache. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34(5):274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Southerst D., Marchand A.A., Côté P. The effectiveness of noninvasive interventions for musculoskeletal thoracic spine and chest wall pain: a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) collaboration. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(7):521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stochkendahl M.J., Christensen H.W., Vach W., Høilund-Carlsen P.F., Haghfelt T., Hartvigsen J. A randomized clinical trial of chiropractic treatment and self-management in patients with acute musculoskeletal chest pain: 1-year follow-up. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(4):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stochkendahl M.J., Sørensen J., Vach W., Christensen H.W., Høilund-Carlsen P.F., Hartvigsen J. Cost-effectiveness of chiropractic care versus self-management in patients with musculoskeletal chest pain. Open Heart. 2016;3(1):e000334. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poulsen E., Christensen H.W., Overgaard S., Hartvigsen J. Prevalence of hip osteoarthritis in chiropractic practice in Denmark: a descriptive cross-sectional and prospective study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(4):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bronfort G., Haas M., Evans R., Leininger B., Triano J. Effectiveness of manual therapies: the UK evidence report. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18:3. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-18-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]