Abstract

Sentinel node biopsy helps in assessing the involvement of axillary lymph node without the morbidity of full axillary lymph node dissection, namely arm and shoulder pain, paraesthesia and lymphoedema. The various methods described in the literature identify the sentinel lymph nodes in approximately 96 % of cases and associated with a false negativity rate of 5 to 10 %. A false negative sentinel node is defined as the proportion of cases in whom sentinel node biopsy is reported as negative, but the rest of axillary lymph node(s) harbours cancer cells. The possible causes of a false negative sentinel lymph node may be because of blocked lymphatics either by cancer cells or following fibrosis of previous surgery/radiotherapy, and an alternative pathway opens draining the blue dye or isotope to another uninvolved node. The other reasons may be two lymphatic pathways for a tumour area, the one opening to a superficial node and the other in deep nodes. Sometimes, lymphatics do not relay into a node but traverse it going to a higher node. In some patients, the microscopic focus of metastasis inside a lymph node is so small—micrometastasis (i.e. between 0.2 and 2 mm) or isolated tumour cells (i.e. less than 0.2 mm) that is missed by the pathologist. The purpose of this review is to clear some fears lurking in the mind of most surgeons about the false negative sentinel lymph node (FNSLN).

Keywords: False negative, Sentinel lymph node biopsy, Clinically overt, Micrometastasis, Tumour emboli

Introduction

The sentinel node biopsy (SNB) is now considered as the standard of care in the surgical management of women with early-stage breast cancer. Sentinel node biopsy helps in assessing the involvement of axillary lymph node without the morbidity of full axillary lymph node dissection, namely arm and shoulder pain, paraesthesia and lymphoedema. The various methods described in the literature identify the sentinel lymph nodes in approximately 96 % of cases and are associated with a false negativity rate of 5 to 10 % [1–3]. These high false negative rates of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) have created a fear in the mind of breast surgeons. The purpose of this review is to clear some fears lurking in the mind of most surgeons about the false negative sentinel lymph node (FNSLN).

Methods of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

Sentinel node is identified with injection of either large particulate material blue dye, e.g. isosulphan blue dye (Lymphazurin 1 %) and methylene blue, or technetium 99m tagged with sulphur colloid or antimony, in sub-areolar, intra-dermal, peri-tumoral or intra-tumoral location of the breast. In Europe, many centres use technetium 99m tagged with colloidal albumin [4–7]. Many authors have demonstrated that the combination of radioisotope and a blue dye for lymphatic mapping improves the sentinel lymph node identification probability compared to the use of a single tracer [8]. The sentinel node is defined as any hot, blue or palpable node in the axillary tissue or a node in which a blue lymphatic vessel is seen to enter. This node(s) is sent for identifying metastasis either by immediate imprint cytology or frozen section or by formalin fixation and haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (and sometimes immunohistochemical (IHC)) staining. Sentinel node biopsy provides an opportunity to the pathologist of a more focused and detailed approach towards a single node. Multiple fine sections of the sentinel node at 2-mm intervals are prepared for detailed microscopic evaluation. In contrast to this, following full axillary node dissection, most pathological laboratories prepare only one histological section per lymph node and the diagnosis of nodal metastasis is made on the basis of histological examination of one section per node [9]. Sometimes, special immunohistochemical stain for cytokeratin is employed to discover any single tumour cell or cluster of tumour cells (occult metastasis), which are often missed on H&E staining. The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) study Z0010, a prospective multicentre study, after an 8-year follow-up of 5210 patients, found that IHC-detected metastasis has no impact on overall survival [10]. That is why neither the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) nor the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend the routine IHC for sentinel lymph node evaluation.

SLNB in Special Situations

Post Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Kuehn et al. (SENTINA trial) evaluated the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. They concluded that even pathologically proven positive sentinel lymph node should undergo repeat SLNB if converted to clinically node negative following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and should be treated accordingly. The overall false negative rate (FNR) for SLNB was 14 %, but this varied with the number of sentinel nodes examined, i.e. 24, 18 and 5 % if one, two or three or more sentinel nodes were examined, respectively [11]. Similarly, the ACOSOG Z1071 trial showed that 41 % of clinically node-positive patients became pathologically node negative after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The sentinel node detection rate was 93 %. The overall FNR among patients with clinically node-positive disease prior to NACT was 13 % among those who had at least two sentinel nodes removed. Like the SENTINA trial, the false negativity rate correlated with the number of sentinel nodes examined (31, 21 and 9 % if one, two or three or more nodes were examined, respectively) [12].

SLNB Post Breast Surgery

Intra et al. first reported on the feasibility of sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy in women with recurrent breast cancer following mastectomy and implant-based reconstruction for previous DCIS [13]. Limitation of this study was that it was a small report of four patients, and follow-up was very short. They identified sentinel nodes in all patients, two of whom had nodal metastasis. The remaining two patients did not have nodal dissection. No axillary recurrences were reported. Another study, by Karam et al. at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, reported on a 10-year experience of SLN biopsy in 20 patients with a history of mastectomy [14]. The SLN identification rate was 65 %. Full axillary dissection was not performed on all patients, so false negative rates are not known. Most recently, Tasevski et al. published a retrospective case series on SLN biopsy in 18 patients with ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence after breast surgery. Reoperative SLN biopsy was successful in 12 out of 18 patients [15]. Cindy et al. assessed the accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy after aesthetic breast surgery in a series of four cases and found that peri-areolar or inframammary incisions are not a contraindication to SLNB [16].

Luini et al. examined the accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy in 543 patients with a history of breast biopsy as previous breast biopsy has been considered a relative contraindication to SLNB. SLNB was guided by performing lymphoscintigraphy on the previous biopsy area. All patients were followed up every 6 months by clinical examination and annually by mammograms and ultrasonography for 5 years. They found that the sentinel node was negative in 70.4 % of cases, and only three cases developed axillary recurrence during follow-up. The sentinel node was identified in 99 % of cases [17].

Validation Phase of a Sentinel Node Biopsy Programme

It is recommended that in the beginning of a sentinel node biopsy programme in a unit/department, a team of surgeons, nuclear medicine physician and pathologist should undergo a rigorous training followed by an initial phase of validating the diagnostic accuracy of identification and detailed histological evaluation of sentinel lymph node. During this validation phase, the team performs 30 to 50 sentinel node biopsy preferably by a combination of tracers; retrieves the radioactive hot, the blue stained or any palpable node; and sends the nodes for pathological evaluation followed by a full axillary lymph node dissection of the rest of the axillary nodes. The sentinel node and rest of axillary nodes are sent as two separate specimens for detailed histological examination. In case the sentinel node(s) is (are) reported to show cancer cells, these are labelled “true positive node”. There are some patients in whom the sentinel nodes are reported to demonstrate no cancer cell, and these are reported as “histologically negative node”. Some of these histologically negative nodes belong to patients in whom there are metastatic deposits in the rest of axillary nodes. These are then labelled “false negative sentinel node”, because the histological report of a sentinel node was wrongly (or falsely) reported as negative. The remaining cases where both the sentinel node and the rest of axillary nodes are reported to harbour no cancer cell are labelled “true negative” because all the axillary lymph nodes are truly free from cancer cells.

It is the histological evaluation of the rest of axillary nodes that is taken as the gold standard for SNB evaluation; however, there are some unique characteristics in the definition, which set out SNB reporting different from other diagnostic tests. These are as follows: The uniqueness of SNB can be best understood with data input in Table 1. The “a” is defined as the positive sentinel node with or without the rest of axillary node positivity. Even if the rest of axillary nodes are negative and even if a single SN is positive, it will be defined as “true positive” with data input in the “a” cell of Table 1. In fact, 40–60 % of all cases of clinically N0 disease in breast cancer have the sentinel node as the only positive node [8, 18]. By definition, the “b” cell in Table is deliberately kept zero, as there are no false positives in sentinel node biopsy. Thus, positive predictive value and specificity are always 100 % in a SNB study due to unique definitions of “a” and “b” cells.

Table 1.

Uniqueness of sentinel node biopsy as a diagnostic test due to non-existence of false positive cases

| Result | Cancer cell (yes) | Cancer cell (no) |

| Positive | True positive (a) | False positive (b) |

| Negative | False negative (c) | True negative (d) |

A false negative sentinel node is defined as the proportion of cases in whom sentinel node biopsy is reported as negative, but the “rest of axillary lymph node(s)” harbours cancer cells. Some of these patients will progress to a clinically overt axillary recurrence. The administration of radiotherapy to the breast and axilla, along with systemic chemotherapy and hormone therapy, reduces the risk of axillary recurrence even if up to two sentinel nodes are positive. Giuliano et al. through their much-publicized ACOSOG Z0011 randomized controlled trial compared the long-term locoregional recurrence and survival in patients undergoing sentinel node biopsy as compared to patients treated by axillary lymph node dissection [19]. It was a phase 3, non-inferiority, multicentre trial that enrolled women with clinical T1–T2 invasive breast cancer with no palpable axillary adenopathy undergoing breast conserving surgery. A total of 891 breast cancer patients with one to two positive sentinel lymph nodes either micrometastasis or macrometastasis participated in this trial. This trial demonstrated that sentinel lymph node biopsy followed by adjuvant therapy might be a reasonable management for patients with early-stage breast cancer among cases with up to two positive sentinel lymph nodes. The axillary recurrence in women, who underwent axillary lymph node dissection in this trial, was 2 out of 420 (0.5 %), whereas in women treated with sentinel node biopsy alone, the risk of axillary recurrence was 4 out of 436 cases (0.9 %). The absolute risk of axillary recurrence is thus very low indeed. So, out of 9 % or 9 out of 100 false negative sentinel nodes, i.e. 9 nodes harbouring cancer cells, only 0.9 % of these 9 nodes were actually manifested clinically.

Thus, false negative sentinel node can be classified as (a) histologically false negative sentinel node and (b) clinically overt false negative sentinel node which can be manifested later as an axillary nodal recurrence.

Definition of False Negative Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

A false negative sentinel node is defined as the proportion of cases in whom sentinel node biopsy is reported as negative, but the rest of axillary lymph node(s) harbours cancer cells. The possible causes of a false negative sentinel lymph node are considered below:

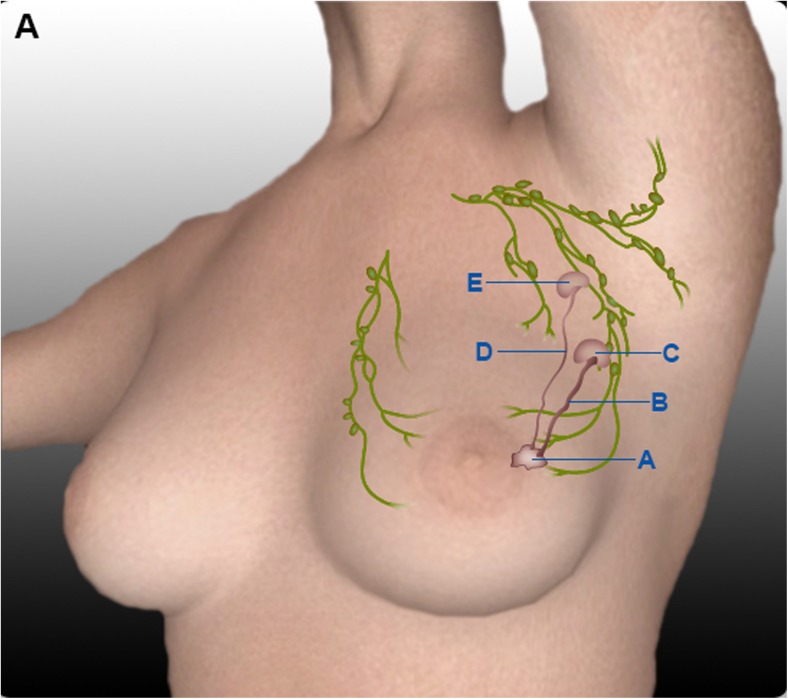

The lymphatic pathway to the truly involved node by cancer is blocked (by tumour emboli, fibrosis of previous surgery or radiotherapy or inflammation like tuberculosis), and an alternative pathway opens draining the blue dye or isotope to another uninvolved node. This uninvolved node is sampled by surgeon and sent as sentinel node. The pathologist reports this sentinel node as negative (Fig. 1).

There are two lymphatic pathways for a tumour area, one opening to a superficial node in the lateral pectoral region and the other opening to the retro-pectoral or inter-pectoral region which is not sampled during sentinel lymph node biopsy. Thus, the positive node is missed and, instead, the surgeon removes another node, which is blue/hot node. Sentinel nodes are usually sampled from the lower level I of the axilla, i.e. the space between the lateral border of pectoralis major muscle and lateral thoracic vein. In 98.2 % of patients, the axillary sentinel lymph nodes are located medially, along with the lateral thoracic vein either above or below the second inter-costobrachial nerve [20]. Since we do not sample the inter-pectoral and retro-pectoral spaces, the truly involved node is missed.

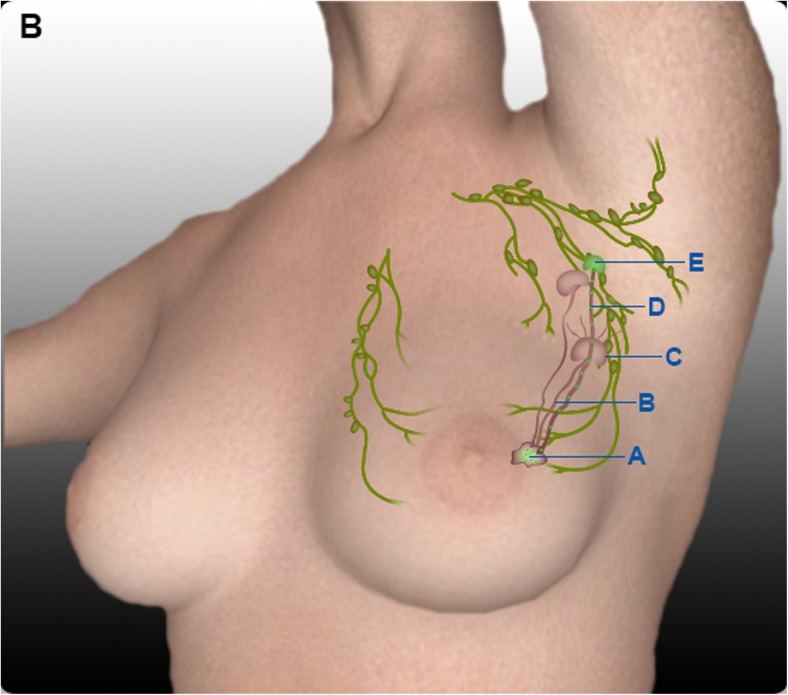

Sometimes, lymphatics do not relay into a node but traverse it going to a higher node (Fig. 2). This is akin to a situation where a fast express train passes through a village railway station without stopping. The afferent lymphatics may traverse a lymph node without opening its contents into the node, thus bypassing a node [21]. Ludwig has described this arrangement of lymphatics, which bypass the filter function of node [22].

In some patients, the microscopic focus of metastasis inside a lymph node is so small—micrometastasis (i.e. between 0.2 to 2 mm) or isolated tumour cells (i.e. less than 0.2 mm) that is missed by the pathologist. It is reported as negative for metastasis, whereas some other nodes in the rest of the axilla are shown to contain tumour cells. Hence, this sentinel node fits the definition of a false negative sentinel node. Such a detection error may be reduced if immunohistochemical staining with pancytokeratin is utilized.

The training of surgeon in performing sentinel node biopsy is poor.

Fig. 1.

False negative lymph node due to lymphatic blockade by tumour embolus. A Breast tumour. B Lymphatic blocked with tumour embolus. C Lymph node with tumour metastasis. D Patent lymphatic carrying dye to non-sentinel lymph node. E Non-sentinel lymph node

Fig. 2.

False negative lymph node due to traversing of lymphatics through sentinel node without relaying into it. A Breast tumour. B Afferent lymphatic to sentinel lymph node. C Genuine sentinel lymph node without tumour metastasis. D Patent lymphatic carrying dye to non-sentinel lymph node (traversing sentinel lymph node without seeding it with tumour emboli). E Non-sentinel lymph node with tumour metastasis

Magnitude of the Problem

The actual magnitude of false negative sentinel lymph node can be better understood by taking an example of 1000 women with early-stage breast cancer and a clinically negative axilla, out of which about a third, i.e. 300, would harbour microscopic nodal metastasis [23, 24]. Of these 300, if we do a sentinel node biopsy with 10 % false negative risk (it is actually the risk or proportion not a rate, as rate by definition should include time in the denominator), 30 (10 %) of 300 cases will be missed on sentinel node biopsy. Of these 30 cases, 9/10, i.e. 27 cases, will be controlled by adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy, chemotherapy and hormone therapy) leaving behind 3 women out of 1000 women with a clinically negative axilla, who will have her missed axillary lymph node (a false negative node) manifested as a clinically overt axillary recurrence. We may call this “clinically overt false negative sentinel node”.

In Giuliano et al.’s Z0011 trial [19], the axillary recurrence in axillary lymph node dissection arm was reported in 5 per 1000 cases of axillary lymph node dissection and 9 per 1000 cases after sentinel node biopsy alone in women with up to two positive sentinel lymph node. Thus, the absolute harm in terms of axillary recurrence due to not doing an axillary lymph node dissection among 1000 women with up to two positive sentinel lymph nodes is 4 (9 − 5 = 4) cases. If we take all women with clinically negative axilla, these 1000 cases with up to two positive sentinel lymph nodes would have arisen from 3000 women (assuming one third of all clinically negative axillae have a positive sentinel lymph node). Hence, of 3000 women with clinically negative axilla subjected to sentinel node biopsy, only 4 will be harmed by not doing a full axillary lymph node dissection. Imagine the harms (painful shoulder, lymphoedema and insensate arm and axilla, costs of procedure and cost of treating complications, operating time) of unnecessary axillary lymph node dissection in 3000 − 4 = 2996 ladies.

Similarly, when we look at the results of NSABP B-32, (the largest randomized controlled trial on sentinel node biopsy on 5611 cases), we find that there were no significant differences in locoregional control, overall survival (OS) or disease-free survival (DFS) between the groups at a median follow-up of almost 8 years. In this trial, women with a clinically impalpable axillary node were recruited to sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) followed by axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) versus SLND followed by ALND only if the SLN was positive. The sentinel lymph node identification rate was 97 % along with a false negative rate of 9.8 % [23, 24].

Another trial by the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) 23-01 trial, where early-stage breast carcinoma patients were randomized to either completion ALND or only SLND, found that there was no significant difference in 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival rate between the two groups. The axillary recurrence rate was only about 1 % after sentinel node biopsy [25]. The ASCO 2014 guidelines advise that there is no need of completion axillary lymph node dissection for patients with less than three positive sentinel lymph nodes if patients are planned for whole breast irradiation [26].

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) conducted a multicentre randomized controlled (AMAROS) trial to compare the effects of axillary irradiation and axillary lymph node dissection in early-stage breast carcinoma patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes. This trial enrolled 4823 patients from 34 centres of nine European countries from 2001 to 2010. These patients were randomized to axillary irradiation or axillary lymph node dissection. After a median follow-up of 6.1 years, it was concluded that the 5-year axillary recurrence was 0.43 % (95 % CI 0.00–0.92) after axillary lymph node dissection versus 1.19 % (0.31–2.08) after axillary radiotherapy. Moreover, axillary radiotherapy resulted in significantly less morbidity [27].

All these studies on sentinel node biopsy have shown that out of all positive axillary nodes (if left in axilla), only a very small fraction would grow to manifest as clinically detectable axillary recurrence. Since the absolute recurrence risk is very low and is very close to that of full axillary lymph node dissection, the false negative sentinel node risk of 8 to 10 % should not alarm us. In future studies of sentinel node biopsy, we should actually look at the incidence of clinically overt false negative sentinel node and not simply “histological false negative sentinel node”.

Future Directions

There is a need for developing a highly sensitive diagnostic test to detect tumour containing lymph node. This will eliminate the problem of false negativity in sentinel node mapping. Our recent effort in this direction is that injecting the tracer intravenously has exhibited interesting results. In this technique, after injection of 3 ml of 20 % fluorescein sodium intravenously about 20–25 min before sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), we observed the presence of fluorescein in tumour containing lymph node with blue light (wavelength 460 nm). This may be due to increased blood flow associated with tumour-induced angiogenesis in the node containing metastatic deposits of more than 1 mm. If we are able to reproduce our results in a large sample of patients, then this technique might help in reducing the problem of false negative sentinel lymph node [28].

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

None.

Presentation or Prior Publication

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Straver ME, Meijnen P, van Tienhoven G, et al. Sentinel node identification rate and nodal involvement in the EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(7):1854–1861. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0945-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):595–600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c0e92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mabry H, Giuliano AE. Sentinel node mapping for breast cancer: progress to date and prospects for the future. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16(1):55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krag DN, Weaver DL, Alex JC, Fairbank JT. Surgical resection and radio localization of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer using a gamma probe. Surg Oncol. 1993;2(6):335–340. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(93)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220(3):391–401. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmons R, Thevarajah S, Brennan M, et al. Methylene blue dye as an alternative to isosulfan blue dye for sentinel node localization. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(3):242–247. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blessing W, Stolier A, Teng S, et al. A comparison of methylene blue and lymphazurin in breast cancer sentinel node mapping. Am J Surg. 2002;184:341–345. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996;276(22):1818–1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540220042028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cserni G. Complete sectioning of axillary sentinel nodes in patients with breast cancer. Analysis of two different step sectioning and immunohistochemistry protocols in 246 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(12):926–931. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.12.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuliano AE, Hawes D, Ballman KV, et al. Association of occult metastases in sentinel lymph nodes and bone marrow with survival among women with early-stage invasive breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:385. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:609. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boughey JC, Simon VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. The role of sentinel lymph node surgery in patients presenting with node positive breast cancer (T0-T4, N1-2) who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy—results from the ACOSOG Z1071 trial. Cancer Res. 2012;72:94s. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS12-S2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intra M, Veronesi P, Gentilini OD, Trifirò G, Berrettini A, Cecilio R, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is feasible even after total mastectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(2):175–179. doi: 10.1002/jso.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karam A, Stempel M, Cody HS, Port ER. Reoperative sentinel lymph node biopsy after previous mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(4):543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.06.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasevski R, Gogos AJ, Mann GB. Reoperative sentinel lymph node biopsy in ipsilateral breast cancer relapse. Breast. 2009;18(5):322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu C, Song DH, Jaskowiak N. The accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy after aesthetic breast surgery: a case series and a review of the literature. Open Reconstructive Cosmet Surg. 2010;3:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luini A, Galimberti V, Gatti G, Arnone P, Vento AR, Trifiro G, et al. The sentinel node biopsy after previous breast surgery: preliminary results on 543 patients treated at the European Institute of Oncology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:159–163. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V, Viale G, Zurrida S, Bedoni M, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet. 1997;349(9069):1864–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliano AE, McCall L, Beitsch P, et al. Locoregional recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection with or without axillary dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node metastases: the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):426–432. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f08f32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clough KB, Nasr R, Nos C, Vieira M, Inguenault C, Poulet B. New anatomical classification of the axilla with implications for sentinel node biopsy. Br J Surg. 2010;97(11):1659–1665. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uren RF, Thompson JF, Howman-Giles RB. Lymphatics. In: Uren RF, editor. Lymphatic drainage of the skin and breast, locating the sentinel nodes. Australia: Harward Academic Publishers; 1999. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig Ueber kurschlusswege der lymphbahnen und ihre beziehungen zur lymphogen krebsmetastasierung. Pathol Microbiol. 1962;25:329. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB. Primary outcome results of NSABP B-32, a randomized phase III clinical trial to compare sentinel node resection (SNR) to conventional axillary dissection (AD) in clinically node-negative breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:18s. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyman GH, Temin S, Edge SB, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1365–1383. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, Meijnen P, Mansel RE, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): a randomized, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qaiser D, Srivastava A, Mehta DS (2015) Detection of tumour containing sentinel lymph node in breast cancer by injection of fluorescence tracer through “dual route” in breast tissue and intravenously. Published in proceedings of PHOTOPTICS 2015—international conference on photonics. Opt Laser Technol:125–128