Abstract

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a chronic, debilitating and progressive disease associated with high morbidity and mortality. Evidence-based medications (EBMs) are the cornerstone of management of patients with HF. In Australia, these EBMs are subsidised by the Commonwealth Government under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Suboptimal dispensing and non-adherence to these EBMs have been observed in patients with HF. Our study will investigate trends in dispensing patterns, as well as adherence and persistence of EBMs for HF. We will also identify factors influencing these patterns and their impact on long-term clinical outcomes.

Methods and analysis

This whole population-based cohort study will use longitudinal data for people aged 65–84 years who were hospitalised for HF in Western Australia between 2003 and 2008. Linked state-wide and national data will provide patient-level information on medication dispensing, medical visits, hospitalisations and death. Drug dispensing trends will be described, drug adherence and persistence estimated and the association with all-cause/cardiovascular death and hospitalisations reported.

Ethics and dissemination

This project has received approvals from the Western Australian Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee and the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee. Results will be published in relevant cardiology journals and presented at national and international conferences.

Keywords: adherence and persistence, evidence-based pharmacotherapy, drug dispensing patterns, outcome measure

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A whole population-based study on long-term dispensing and adherence/persistence patterns of evidence-based medications for heart failure.

Time-series medication data from an administrative source allows estimation of medication adherence and persistence.

Longitudinal patient-level linked administrative data will assess comorbidities and use of medical services that may impact on medication dispensing, subsequent hospitalisations and death.

The effect of underusage and medication adherence on late clinical outcomes will be determined.

The study cohort was restricted to age 65 years or older to capture the relevant drugs recorded in the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme database.

Drug doses are not recorded in the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme database, so the quantity taken per day is unknown.

Distinguishing between heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and preserved ejection fraction was not possible.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a chronic, debilitating and progressive condition which is associated with high mortality, morbidity and disability.1 Evidence-based medications (EBMs) are the cornerstone in managing patients with HF.2–12 Clinical trials have shown that ACE inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and β-blockers (BB) have significantly decreased the overall mortality and morbidity for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). International and national guidelines1 13 recommend the use of ACEI (or ARB if intolerant to ACEI) and BB as first-line therapy in patients with symptomatic HFrEF. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) are generally reserved for patients with HFrEF and persistent symptoms despite treatment with an ACEI and BB.1 14–16 Digoxin may also be considered as it reduces the risk of HF rehospitalisation in patients with sinus rhythm and worsening HF despite ACEI and BB.1 17 18

In HF, uptake and adherence of EBMs are associated with a decrease in the rates of rehospitalisation and death.19–21 Patients with good adherence to EBM have better outcomes than those who stop their long-term therapy.22 23 Although 1-year adherence to BB and ACEI has improved over time in patients discharged after their first hospitalisation for HF,24 poor adherence to EBM remains a significant barrier to enhancing effectiveness of current treatment.25 Medication non-adherence is a growing concern in the light of evidence of its high prevalence and association with adverse outcomes and increased healthcare costs.26 To date, there are limited data on the adherence or persistence of HF medications in the general population. A better understanding of factors affecting adherence/persistence of EBM, which are amenable to interventions, is crucial to improving outcomes in HF.

Accordingly, the aim of our study is to use linked data from State and Commonwealth administrative data sets to evaluate trends in dispensing of HF EBMs, medication adherence and persistence, and outcomes in people aged 65–84 years following hospitalisation for HF in Western Australia (WA). The specific research objectives are:

To investigate trends in prescription uptake and long-term adherence and persistence of EBMs in 30-day survivors following discharge for HF between 2003 and 2008.

To assess determinants of dispensing and adherence/persistence of EBMs.

To investigate the association between adherence/persistence to EBMs for HF and subsequent clinical outcomes including HF rehospitalisation and death.

Methods and analysis

This is a population-based retrospective cohort study of people aged 65–84 years with a discharge diagnosis of HF in WA between 2003 and 2008, and who survived 30 days postdischarge.

Data sources

The study will use statutory government-held administrative data of person-linked health information (table 1).27 This includes data from the: (1) Hospital Morbidity Data Collection (HMDC) and death registry, which are two of the core data sets of the WA Data Linkage System,27 and (2) Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which is from the Commonwealth Department of Health in Australia. The HMDC contains information on people admitted to any hospital in WA, both public and private. The PBS data set includes information on medications dispensed from Australian pharmacies. Fields include age and sex, dates of prescription and supply, quantity supplied, broad prescriber specialty group, derived patient category, PBS item code and Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code.28 The PBS provides medicines to the Australian population at a subsidised cost, making them more affordable. People who have a healthcare concession card are eligible to obtain their PBS-subsidised medications at a reduced cost. The combination of linked data from State and Commonwealth sources will allow us to assess, at the individual level, hospital admissions, medication dispensing, an estimate of medication adherence and persistence, and associations with subsequent clinical outcomes.

Table 1.

Information available from the various data sources in the study

| Data set | Fields | Period covered |

|---|---|---|

| HMDC | Demographic data, diagnosis, comorbidities and history, procedures, dates of admission and discharge | 1980–2014 |

| Death data set | Cause of death and date of death | 1980–2014 |

| PBS | Date of prescription and supply, PBS item code,* ATC code, quantity supplied, number of scripts, derived patient category | 1 July 2002 to 30 June 2011 |

*PBS item code identifies the drug and strength dispensed.

ATC, Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical; HMDC, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Study cohort

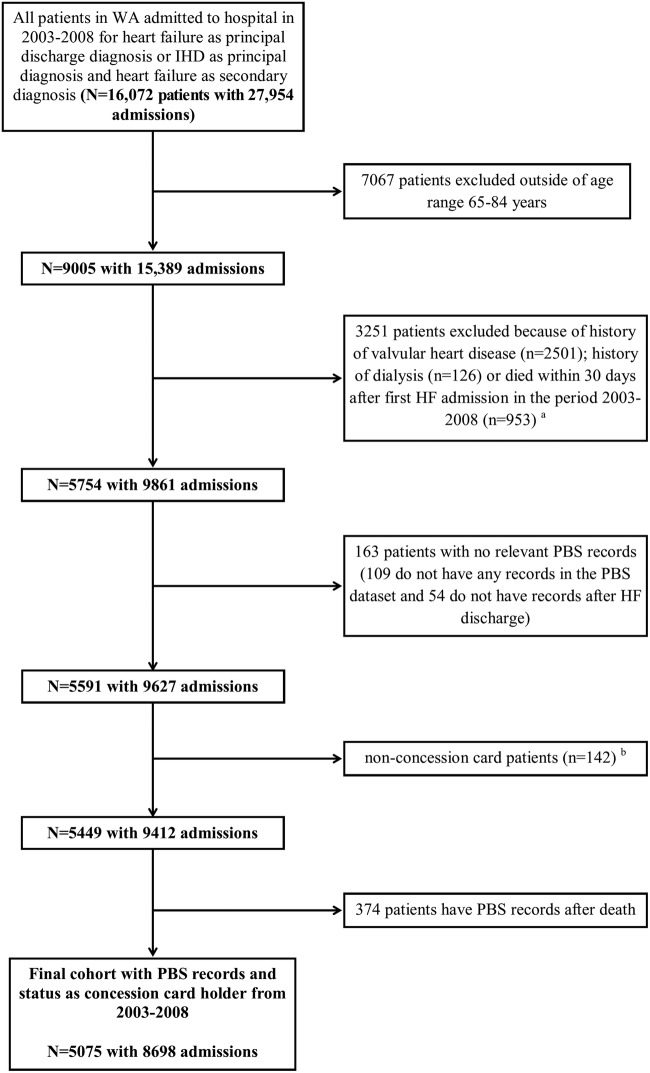

The study cohort consists of residents of WA aged 65–84 years with a hospital discharge diagnosis of HF in WA during 2003–2008 and who had PBS records. We excluded very elderly patients aged 85 years or older because of an expected low short-term survival. In addition, 30-day death after admission for HF can be as high as 20%,29 so we excluded people who died within 30 days of the HF admission. The cohort selection process is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection process for the HF cohort from HMDC, death and PBS data sets. aSome patients had more than one excluded conditions. bNon-concession card (general) patients are those who do not qualify for a concession card in Australia. HMDC, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection; HF, heart failure; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; WA, Western Australia.

The PBS data set contains complete recording of all dispensed medications approved for HF in concession card holders, comprising 96% of the total HF cohort. Our PBS data were available from mid-2002 to mid-2011, so we limited the study cohort to 2003–2008 to allow inclusion of PBS data for 6 months before and at least 2.5 years after this period.

Identifying HF

HF was identified from the discharge diagnosis fields of the HMDC using codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 9th Revision (ICD-9, including the Clinical Modification ICD-9-CM) and 10th Revision Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM). An admission for HF was defined as: (1) HF as principal discharge diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 428, ICD-10-AM codes I50); or (2) HF as the secondary discharge diagnosis where ischaemic heart disease (ICD-10-AM codes I20-I25) was the principal diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they had a history of valvular heart disease in any diagnosis field, or heart valve surgery or renal dialysis in any procedure field (ICD codes listed in online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2016-014397supp_tables.pdf (228.1KB, pdf)

The coding of HF as principal discharge diagnosis in the HMDC has been validated using the Boston diagnostic criteria, with a positive predictive value of 92.4% for definite HF and 98.8% for a combined definite or possible HF.30

Definition of comorbidity

Comorbidities will be identified from their relevant ICD codes from any of the discharge diagnosis fields in the HMDC by applying a fixed 20-year look-back period from the initial (index) HF admission. Comorbidities include ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, renal failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, peptic ulcer disease and gastrointestinal bleeding (ICD codes in online supplementary table S1). Similarly, a Charlson Comorbidity Index31 will be calculated as a composite measure of comorbidity for each index case using a fixed look-back period. Some patients in the study cohort may have pre-existing HF and some may be new cases, so we will identify those with a history of HF using a fixed 20-year look-back period.

Dispensing patterns of evidence-based drugs for HF

The EBMs for HF are shown in table 2. Trends in drug dispensing patterns will be assessed based on fixed periods of 30 days, 6 months, 1, 2 and 3 years after hospital discharge. Dispensing patterns will be assessed by drug groups and combinations (eg, any ACEI/ARB, any BB, any MRA, ACEI/ARB+BB, ACEI/ARB+BB+MRA). We will determine the proportion of patients who are dispensed these drugs at each time point as well as determine trends in the whole study period. The continuity of drug dispensing (adherence/persistence) will be assessed for the cohort for periods of up to 3 years to estimate the proportion of continuous use over time (patients identified in the second half of 2008 will have 2.5–3 years of drug data postdischarge). Landmark analysis will be used to develop models of association between drug persistence and outcomes, with landmark times of 6 months, 1 and 2 years (a 3-year landmark will also be investigated in the 2003–2007 cohort, because some patients in 2008 will not have 3 years of postdischarge PBS data). In addition, using our person-based linked file, we can identify the impact of the more serious adverse effects of drugs (eg, renal failure). Since we have time-series PBS data, we will also be able to identify any change of drug groups (eg, ACEI to ARB). Finally, we can explore and identify possible clinical conditions that may impact on use of specific EBM drugs, such as renal failure and chronic respiratory conditions (see ICD codes in online supplementary table S1).

Table 2.

Evidence-based medications for heart failure

| Drug or drug group | ATC code | Generic name |

|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | C09AA | Captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, trandolapril |

| ARB | C09CA | Valsartan, losartan, candesartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, eprosartan |

| β-blockers | C07AB | Propranolol, atenolol, metoprolol tartrate, metoprolol succinate, nebivolol, carvedilol, bisoprolol |

| MRA | C03DA | Spironolactone, eplerenone |

| Cardiac glycoside | C01AA | Digoxin |

ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ATC, Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Adherence and persistence to medications based on dispensing data

There are different methods for quantifying the consumption of medications, including subjective methods (eg, self-report) and objective methods (eg, adherence/persistence, blood tests). Adherence and persistence are the main methods for describing a patient's propensity to take medications for the appropriate length of time at the appropriate doses.32 For this study, we will define adherence as the proportion of prescribed doses of the medication taken by the patient over a specific period,32 and the persistence as the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy.32

In the PBS data set, we do not have data on dose, which is required for accurate estimation of the duration of use, which is required in estimating adherence and persistence. Hence, we will investigate several methods to estimate this. First, there is the defined daily dose published by the WHO,28 and a similar prescribed daily dose from the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) data collection.33 The latter is from a sample of Australian general practitioners and would be a more accurate representation of average daily dose in Australian clinical practice. In addition, we will estimate the duration of use from the 75th centile of the distribution of time to next supply date.34

Since there is no gold standard for measuring adherence in administrative data, we will apply two common methods:32 (1) medication possession ratio (MPR) and (2) proportion of days covered (PDC).32 Each has strengths and limitations as detailed in online supplementary table S2.35–38 These methods calculate adherence as the proportion of days supplied from the first and last pharmacy fill dates in a specific observation period, with variations on the start and end dates. Values range from 0% (non-adherence) to 100% (complete adherence), although the MPR value may exceed 100%, indicating an oversupply of medication. Both results can be presented as categorical or continuous variables. Although these methods provide a similar result when calculating the adherence for a single drug, in a comparative study by Nau,35 the PDC provided a more conservative estimate of adherence when there was frequent drug switching and concomitant therapy with polypharmacy.

Likewise, there is no universal agreement for calculating persistence. As a result, we will use the refill-sequence method,39 which is widely used in health research. The strengths and limitations of this are described in the online supplementary table S2.19 39 40 The refill-sequence model calculates persistence by determining if a patient has refilled a prescription within a predefined number of days. The results from this model can be presented as a binary variable (eg, <80% persistence, ≥80% persistence).

The PBS data set also does not include medications received by inpatients at most hospitals in WA or at discharge during the study period. Hence, for patients who were admitted to hospital or had holidays during the study period, dispensing records will be absent from the PBS. Additional periods of absence, or gaps, in treatment can occur for other reasons, such as patients not refilling their prescriptions for a short period of time after they have finished their current supply. These gaps will be considered when calculating adherence and persistence, such as when the gaps are concordant with hospitalisations identified from the hospital morbidity data set.

Statistical analyses

The Cochran-Armitage trend test will be used to evaluate trends for dispensing of medications and adherence using the calculations of MPR and PDC. Follow-up will be to 30, 180 days, 1, 2 and 3 years from discharge date of the index HF admission and first EBM supply date, respectively. Kaplan-Meier methods will be used to assess the proportion of patients still dispensed medications over time following the first supply of EBM (persistence).

Multivariable logistic regression models will be used to investigate determinants of the dispensing of EBMs. Factors to be investigated include sociodemographic (eg, sex, age and hospital type), clinical (eg, comorbidities, Charlson score) and medication (eg, number of EBMs, interaction of common drugs, adverse effects requiring hospitalisation (HMDC data) and other interaction effects (eg, gender×medications, age×medications)). Cox regression models will be used to investigate the determinants (listed above) of persistence to treatment such as time to first discontinuation. Tests for violation of the Cox proportional hazards assumption will be ascertained prior to running the main models.

Multivariable logistic regression models based on major sociodemographic and clinical factors will be developed to estimate the propensity to be initially dispensed medications. Propensity score methods41 will be used to control for measured and unmeasured confounders when assessing the associations between adherence to EBMs and subsequent outcomes.

Multivariable Cox regression models will also be used to examine the association between medication adherence/persistence and clinical outcomes. The primary outcomes will be death, readmission for HF as a principal diagnosis and the composite of these. Secondary outcomes are non-elective (emergency) readmission for any cause and cardiovascular-related deaths. In the models, we can investigate adherence thresholds and see how they affect outcomes at different threshold levels.

We can also model the reduction in persistence over time and compare groups with varying levels of reduction. Given that the change in persistence is expected to have a more gradual effect on outcomes (eg, over at least 6 months), we will use the landmark analysis method to model the association between reduction in persistence and outcomes.42 43 The landmark time points will be at 6-month intervals, and we will model the risk over the next 6 months against the average level of persistence over the previous 6 months for a total follow-up period of 3 years.

Dissemination

Results of this study will be published in relevant medical journals. Results will also be presented at relevant national and international conferences. Additional communication of our results will occur through our collaboration with the National Prescribing Service (NPS MedicineWise, http://www.nps.org.au) and health practitioners.

Discussion

Despite advances in medical therapy, the morbidity and mortality associated with HF remain high. Non-adherence to EBM in HF remains a major barrier to enhancing effectiveness of current treatments and leads to poorer outcomes.22 26 This population-based study will use contemporary data to examine patterns of EBM uptake and adherence/persistence of treatment in a ‘real-world’ HF population. The PBS data set provides information about dispensing of medication rather than prescribing, and although we are not able to determine true prescribing patterns in the population, the dispensing data are a reasonable indicator of prescribing. The findings will allow us to identify current evidence–treatment gaps and determinants of underprescription and adherence/persistence of EBMs, and suggest strategies whereby the burden of HF can be reduced by more optimal therapy. Observational studies of evidence-based therapies in the general population are valuable because they reflect prescribing patterns and consumer adherence in the ‘real world’ in contrast to the ideal conditions of clinical trials. Further, patients included in trials are generally much younger and with less comorbidity than is encountered in clinical practice. HF registries such as IMPROVE HF44 that include patient samples from participating clinical practices have been able to demonstrate a positive association of HF process-of-care measures (such as EBM use) and survival, but this needs to be confirmed in whole population-based studies. Patients included in our study are aged 65 years and older with hospitalised HF, and therefore represent the more advanced spectrum of HF cases in the community. However, these patients are also more likely to derive survival benefit from optimal prescription of evidence-based therapies.

Previous studies have estimated the adherence/persistence to EBMs for HF. However, results are variable, ranging from 10% to 94%.19 45 Subjective methods of measuring medication adherence/persistence contribute to the variability. A majority of studies used self-reported questionnaires to determine the adherence/persistence.46 47 However, this method is often poorly concordant with more objective measures of adherence/persistence.48 While objective measurements, such as pill count and Medication Event Monitoring Systems,49 50 are widely used in clinical trials, these methods require direct patient contact, and are not feasible when applied to a population-based study. Gislason et al19 used the refill-sequence method to evaluate persistence. However, hospital data were lacking, and the persistence may have been underestimated from gaps in the pharmacy data set due to hospitalisations.

Population-based linked data provide a novel and more precise way to estimate adherence/persistence. Using PBS data, we can estimate these two measurements to cardiac medications for nearly all persons aged 65 years or older who were admitted to hospital in WA. We can check if gaps in PBS data for individual patients relate to hospitalisation periods (by checking in the HMDC data). If patients are hospitalised during the gaps in PBS data, we can assume that the patient persists in taking the medications. Data are scarce and variable on optimal thresholds for medication adherence/persistence in patients with HF.50 51 Our data will allow the estimation of thresholds of adherence/persistence below which outcomes become suboptimal. Finally, our linked data allow the estimation of long-term adherence/persistence and cause-specific and all-cause morbidity and mortality as a function of adherence/persistence. Further, this analysis will account for comorbidities that may confound the association between drug adherence/persistence and outcomes. As far as we know, there are no previous studies to estimate this for HF in a population-based setting in Australia, and evidence linking adherence/persistence with long-term outcomes is also scarce internationally.

Strengths and limitations

Previously we have reported that dispensing rates of proven cardiac preventive drugs in WA are similar to other states in Australia, suggesting that results in WA can be generalised to the Australian population.52 A population-based study reduces the likelihood of a ‘healthy adherer effect’, encountered in some studies investigating drug adherence and outcomes.

The limitations of this study are first we are unable to distinguish between HF with reduced and preserved ejection fraction using the HMDC data set. Second, PBS data do not provide information on drug dose and frequency, nor reasons for prescribing the medications. However, we can use the hospitalisation data to identify comorbidities and this will provide a list of possible indications for drugs that may have dual use. Also, hospitalised patients with HF aged <65 years were excluded, but this represents a minority (∼20%) of all patients with incident HF hospitalisation in WA during the study period.29 Finally, medication usage in Aboriginal West Australians is largely under-recorded in the PBS.

Conclusion

This population-based study will estimate the association between dispensing and adherence/persistence to EBMs for HF and subsequent clinical outcomes. It will address the problems around the effectiveness of these drugs in the real-world population, accounting for sociodemographic factors and comorbidities. The results will inform on possible interventions and strategies for health policymakers and healthcare providers to improve the rate of EBM use in the population, and to ensure adequate long-term adherence/persistence by consumers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Australian Department of Health for providing the cross-jurisdictional linked data used in the study. The authors also thank the Data Linkage Branch and Data Custodians of the WA Department of Health for providing the linked HMDC and death data.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Frank Sanfilippo at @CVRG_UWA

Contributors: XQ wrote the first draft of the manuscript and will be the data analyst. The study was conceived by FMS, with all authors contributing to the study design and planning. Biostatistical and epidemiological methods were refined by FMS, T-HKT, JH and TB. Clinical input towards design, analysis and interpretation of results was provided by JH. All authors provided critical feedback during manuscript development and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research is supported by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC project grant 1066242).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee approvals have been obtained from the Western Australian Department of Health (#2014/11); Australian Department of Health (XJ-16); The University of Western Australia (RA/4/1/8065) and the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (Ref 572).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Data sharing statement: The authors will consider requests for data sharing on an individual basis, with an aim to sharing data whenever possible for appropriate research purposes. However, the research project uses third party data derived from Australian (State or Federal) government registries, which are ultimately governed by their ethics committees and data custodians. Therefore, any requests to share these data will be subject to formal approval from their ethics committees overseeing the use of these data sources, along with the data custodian(s) for the data of interest.

References

- 1.Atherton JJ, Bauersachs J, Carerj S et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:891–975. 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. The SOLVD investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327:685–91. 10.1056/NEJM199209033271003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. The SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med 1991;325:293–302. 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: metoprolol CR/XL randomised intervention trial in-congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999;353:2001–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04440-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjalmarson A, Goldstein S, Fagerberg B et al. Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure. JAMA 2000;283:1295–302. 10.1001/jama.283.10.1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Packer M, Coats AJS, Fowler MB et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1651–8. 10.1056/NEJM200105313442201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1349–55. 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maggioni AP, Anand I, Gottlieb SO et al. Effects of valsartan on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure not receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:1414–21. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02304-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohn JN, Tognoni G. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1667–75. 10.1056/NEJMoa010713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMurray JJ, Östergren J, Swedberg K et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial. Lancet 2003;362:767–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14283-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:9–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11181-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (Chronic Heart Failure Guidelines Expert Writing Panel). Guidelines for the prevention, detection and management of chronic heart failure in Australia updated October 2011. http://heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/Chronic_Heart_Failure_Guidelines_2011.pdf

- 14.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709–17. 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011;364:11–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1009492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1309–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa030207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:525–33. 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lader E, Egan D, Hunsberger S et al. The effect of digoxin on the quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 2003;9:4–12. 10.1054/jcaf.2003.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ et al. Persistent use of evidence-based pharmacotherapy in heart failure is associated with improved outcomes. Circulation 2007;116:737–44. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teng THK, Finn J, Hung J. The effect of evidence-based medication use on long-term survival in patients hospitalized for heart failure in Western Australia. Med J Aust 2010;192:306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krantz MJ, Ambardekar AV, Kaltenbach L et al. Patterns and predictors of evidence-based medication continuation among hospitalized heart failure patients (from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure). Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1818–23. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molloy GJ, O'Carroll RE, Witham MD et al. Interventions to enhance adherence to medications in patients with heart failure a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:126–33. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR et al. A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ 2006;333:15 10.1136/bmj.38875.675486.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb DA, Eurich DT, McAlister FA et al. Changes in adherence to evidence-based medications in the first year after initial hospitalization for heart failure observational cohort study from 1994 to 2003. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:228–35. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.813600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekman I, Swedberg K. Patients’ persistence of evidence-based treatment of chronic heart failure: a treatment paradox. Circulation 2007;116:693–5. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.719492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 2009;119:3028–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holman CDJ, Bass AJ, Rouse IL et al. Population based linkage of health records in Western Australia: development of a health services research linked database. Aust N Z J Public Health 1999;23:453–9. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2015. Oslo, 2014. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_publications/guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng THK, Finn J, Hobbs M et al. Heart failure incidence, case fatality, and hospitalization rates in Western Australia between 1990 and 2005. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:236–43. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.879239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teng THK, Finn J, Hung J et al. A validation study: how effective is the Hospital Morbidity Data as a surveillance tool for heart failure in Western Australia? Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:405–7. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:676–82. 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raebel AM, Schmittdiel JJ, Karter LA et al. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care 2013;51(Suppl 3):S11–21. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b1d2a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH), 2016. http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/fmrc/beach/

- 34.Pottegård A, Hallas J. Assigning exposure duration to single prescriptions by use of the waiting time distribution. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:803–9. 10.1002/pds.3459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nau DP. Proportion of days covered (PDC) as a preferred method of measuring medication adherence. Springfield, VA: Pharmacy Quality Alliance, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007;10:3–12. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M et al. An empirical basis for standardizing adherence measures derived from administrative claims data among diabetic patients. Med Care 2008;46:1125–33. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA et al. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:1280–8. 10.1345/aph.1H018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caetano PA, Lam J, Morgan SG. Toward a standard definition and measurement of persistence with drug therapy: examples from research on statin and antihypertensive utilization. Clin Ther 2006;28:1411–24. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gislason GH, Buch P, Friberg J et al. Long-term compliance with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1153–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson JR, Cain KC, Gelber RD. Analysis of survival by tumor response. J Clin Oncol 1983;1:710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dafni U. Landmark analysis at the 25-year landmark point. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4:363–71. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB et al. Associations between outpatient heart failure process-of-care measures and mortality. Circulation 2011;123:1601–10. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.989632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunlay SM, Eveleth JM, Shah ND et al. Medication adherence among community-dwelling patients with heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:273–81. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.George J, Shalansky SJ. Predictors of refill non-adherence in patients with heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:488–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02800.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JMO, Zhang Y et al. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am Heart J 2005;150:982 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR et al. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care 2004;42:649–52. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129496.05898.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 1999;21:1074–90. 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80026-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu JR, Moser DK, De Jong MJ et al. Defining an evidence-based cutpoint for medication adherence in heart failure. Am Heart J 2009;157:285–91. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M et al. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2303–10. 10.1185/03007990903126833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gunnell AS, Knuiman MW, Geelhoed E et al. Long-term use and cost-effectiveness of secondary prevention drugs for heart disease in Western Australian seniors (WAMACH): a study protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006258 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014397supp_tables.pdf (228.1KB, pdf)