Abstract

The aim of the project was to improve patient experience for people in Tower Hamlets Specialist Addictions Unit in order to increase satisfaction by 25% in 12 months starting in August 2014.

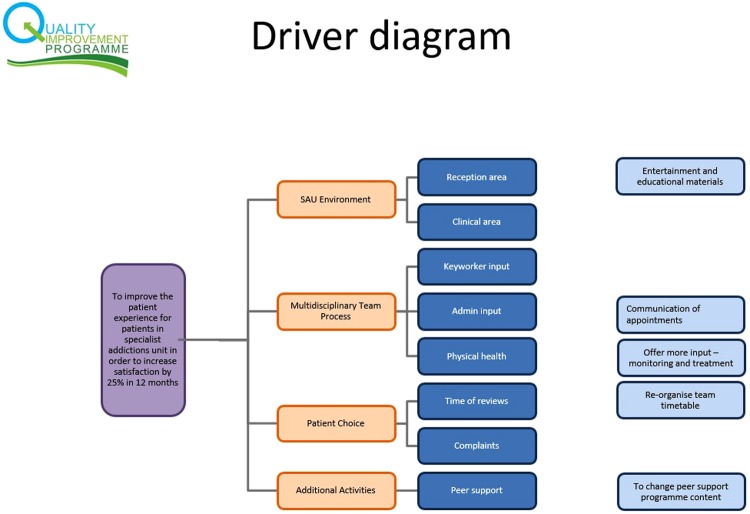

The team used the model for improvement as part of ELFT's quality improvement programme to support iterative cycles of testing and learning. This involved support from the Trust's quality improvement team. The theory of change was visualised through a driver diagram. A number of outcomes were measured and plotted over time - patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and attendance to peer support groups. The impact of changes was then observed using the plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycles. The changes that positively influenced the outcomes were continued and ones without such impact were discontinued.

The most successful intervention to improve patient satisfaction so far was the introduction of peer support facilitation for the “Breakfast club” - recovery orientated meeting of patients with less emphasis on the medical aspects of treatment. Staff satisfaction is proven to be one of the best determinants of patient experience, so this is also measured and plotted over time together with patient's satisfaction and attendance.

Service user satisfaction improves attendance and outcomes in this difficult-to-engage group of patients (people with both substance misuse and mental health problems). Patient perspectives and priorities might be quite different to that of the clinical team, further supporting the importance of involving and engaging them in any quality improvement work. Involving peer support workers in improving engagement of people with substance misuse related problems appears essential.

Problem

This project took place in the Tower Hamlets Specialist Addictions Unit in London, United Kingdom, which is run by East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT). The unit provides community substance misuse treatment for the most complex patients living in the borough of Tower Hamlets, with an often chaotic pattern of use including intravenous poly use, pregnant substance misusers, and dual diagnosis.

The problem identified was patient experience. The verbal feedback received from patients was that the atmosphere in the service was not helping them feel relaxed and did not make them want to engage with treatment. Additionally, very low attendance at the groups organised for the service users indicated that this could be improved. These were groups held on a weekly basis which provided coffee and breakfast to encourage more patients to come in the morning.

The patients identified that the constantly changing facilitators from a “professional” background did not entice them to attend. They proposed using facilitation by peer support workers, which had been used in other services previously.

In addiction services the engagement of patients in treatment is one of the most important and challenging issues. We know that the treatments that are used do work, but that compliance with treatment can be a challenge.1

Improved patient satisfaction is likely to directly translate into better attendance to the service and improved compliance with treatment and with this the clinical outcomes.2 One of ELFT's strategic improvement priorities is to provide the right care at the right time at the right place. Working on the experience and satisfaction of service users aligned with this Trust-wide priority. The aim of the project was to improve patient experience for people in Tower Hamlets Specialist Addictions Unit in order to increase satisfaction by 25% in 12 months starting in August 2014.

Please see the attached driver diagram (diagram 1) for a more graphical representation of this.

Diagram 1

Background

There is limited literature on improving patient experience in addiction services, but our background research identified a number of themes.

It is essential to involve patients in quality improvement work as often the service user perspective and priorities might be very different to that of the clinical team.3 The success of this kind of project is often linked with meaningful patient participation.

More specifically, involving peer support workers in the delivery of addiction services results in improving engagement of people with substance misuse related problems. This appears to be one of the most successful strategies in improving patient participation and attendance.4 5

Interviews with patients indicated the need for having a peer support worker running groups and activities, with positive experiences from other addiction services that the patients previously used. The feedback included the fact that it was easier to open up to someone who shared similar experiences, as well as looking up to them as a role model who was able to overcome addiction.

In quality improvement work it is important to look at the unintended consequences of the changes that are implemented; the so-called balancing measures. One of these could be the impact of the changes on the staff working in the service. There is evidence in the literature that staff engagement and satisfaction is a very good predictor of patient experience.6 7

Baseline measurement

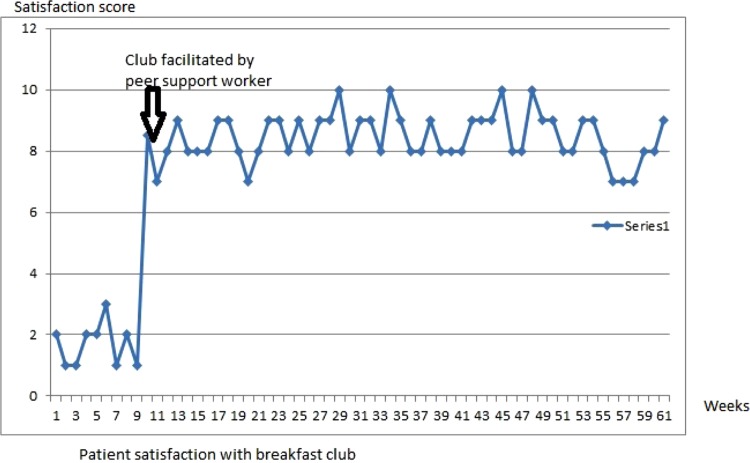

We reviewed patient satisfaction scores collected by the service prior to the commencement of the project (see graph 2). Unfortunately, this was only recorded once a year but still provided some data for comparison.

Chart 2. Patient satisfaction with breakfast club

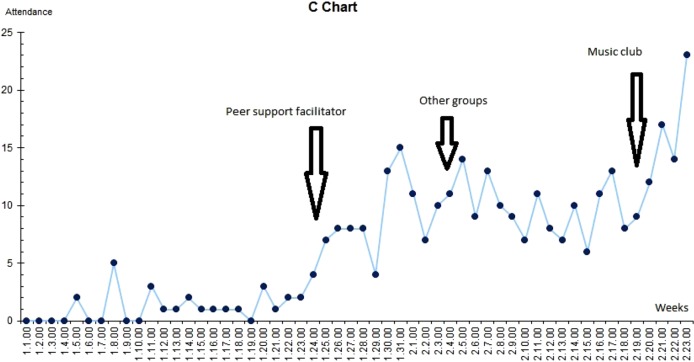

As a process measure, we decided to look at the number of people attending breakfast club (see graph 1) and other groups as these data was already collected and easily available. It was possible to monitor the impact of the changes implemented as these data was collected continuously by the reception staff.

Chart 1. Number of patients attending each week

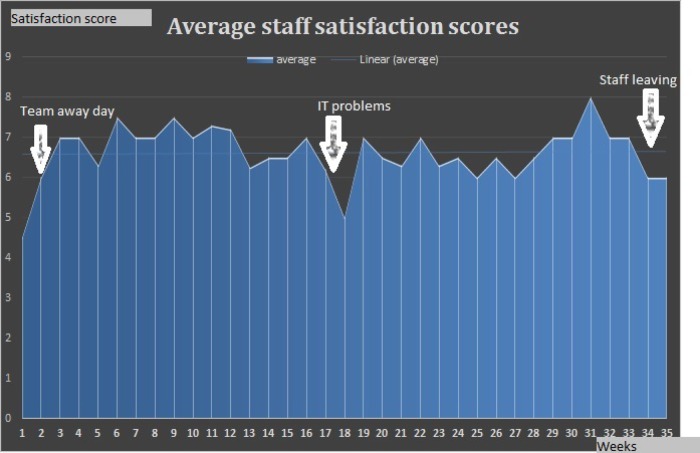

As a balancing measure, we recorded staff satisfaction (see graph 3) and in this case, no prior data were available before the start of the project. It is important to check if the changes implemented have a negative impact on staff satisfaction as this is a good predictor of patient satisfaction.6

Chart 3. Staff satisfaction scores (1–10)

Design

Looking at the feedback from service users and the background research described above, the team chose to test the idea of supporting a peer support worker to lead the breakfast club and other group activities. This change idea was designed together with the patients to reflect their needs and interests. The funding for the peer support worker is stable and both commissioners and the Trust supported this approach of collaborating with patients.

Two other change ideas were tested. A female-only cinema was an example of an intervention that did not prove to be successful in our setting. A music studio was also developed within the service, following interest from both service users and the peer support worker.

Strategy

PDSA cycle 1: The objective was to test whether a breakfast club facilitated by a peer support worker would engage service users better. Patients were informed in a number of ways: by their individual keyworkers, posters in the reception area, as well as the peer support worker pro-actively approaching patients who were waiting to be seen. This has gradually increased the number of patients engaging in the activities as well as presenting to their keyworking appointments.

PDSA cycle 2: Based on feedback from patients, a number of new groups and activities were tested. Unfortunately some of these were more successful than others, and there were different reasons for the failure of certain groups (service and patient related).

PDSA cycle 3: A common interest of the peer support worker and a group of service users in playing musical instruments and recording the music provided the basis for this cycle. Initially a basic music studio was equipped by the team. Following the sourcing of external funds, professional guitars, turntables, microphones, mixer, and recording equipment were purchased by the team. This is also shown in supplementary figure 2 (see supplementary file - PDSA cycle 1+2+3).

bmjqir.u205967.w2458supp.pdf (162.1KB, pdf)

Results

There was existing data on breakfast club attendance prior to starting the project and this was used as baseline data (graph 1). Additionally the team collected retrospective satisfaction/experience scores and continued to collect it throughout the time of the project (graph 2).

The attendance and patient satisfaction scores improved significantly with the change of facilitator (attendance increased five to seven times, satisfaction moved from an average of 2/10 to an average of 9/10).

The balancing measure of staff satisfaction (graph 3) appeared to fluctuate more, with other factors having more influence on this than the interventions tried to improve patient experience (as an example, there was a significant dip when IT systems went offline).

Lessons and limitations

The most successful intervention to improve patient satisfaction was the introduction of peer support facilitation for the “Breakfast club” - a recovery orientated meeting of patients with less emphasis on the medical aspect of treatment. Staff satisfaction is proven to be one of the best determinants of patient experience, so this is also measured and plotted over time together with patient's satisfaction and attendance.

The biggest surprise in the running of the project was the impact of changes in staffing on the project. A few members of the initial project team left, and the peer support worker progressed to the role of keyworker.

There were a number of limitations to the project. In terms of generalisability, the diverse setup of addiction services in different localities might make it difficult to spread this type of intervention. With increasingly constrained budgets any improvement activity (and particularly focus on patient experience rather than safety or effectiveness) can be seen by commissioners as an unnecessary extra.

Some of the changes in the results can be seen as a random variation (particularly the staff satisfaction scores), but it is much less likely for patient attendance and satisfaction as these shifted significantly and were temporally linked with the tested interventions.

As with every observational study there is a possibility of observer effect (Hawthorne effect) influencing the findings, but I am not aware of any bias or confounding that would affect our results.

Conclusion

The results indicate the importance of peer support workers in patient engagement and satisfaction. Involving service users in quality improvement projects is very important, increasing the chances of implementing successful changes. Staff satisfaction is an important determinant of patient experience and should be monitored and improved in parallel.

These conclusions were consistent with the background publications on the topic, but the specific local variation needed to be taken into consideration (for example, the need for female-specific activities, especially for women from Muslim background).

Looking at the wider context of the team and its environment is critical in considering sustainability of improvement work, as changes within the team or the wider health and social care system can impact the ability of a team to work together cohesively or sustain gains made through quality improvement.

Acknowledgments

Mr Andrew Matheou (peer support worker), Ms Dayo Agunbiade (team manager), Ms Jeannine Cox (CPN and keyworker), Mr Arrvind Moheeput (project manager and QI coach), Dr Alexander Verner (team consultant), Dr Ron Alcorn (clinical director) all the other members of TH SAU, volunteers and patients that helped with this project.

This project was supported throughout by the ELFT QI team and in particular Dr Amar Shah, Mr James Innes and Ms Tsana Rawson.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: Nothing to declare.

Ethical approval: Local policy indicated that no ethical approval was needed. Quality improvement work was part of wider QI activity in the East London NHS Foundation Trust.

References

- 1.Drug Misuse and Dependence: UK Guidelines on Clinical Management, Public Health England, February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker Marshall H, Maiman Lois A. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance. J Community Health 1980;6:113 DOI10.1007/BF01318980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Deventer C, McInerney P, Cooke R. Patients' involvement in improvement initiatives: a qualitative systematic review. The JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 2015; 13:232–90. ISSN 2202-4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boisvert RA, Martin LM, Grosek M, Clarie AJ. Effectiveness of a peer-support community in addiction recovery: participation as intervention. Occup Ther Int 2008;15:205–20. doi: 10.1002/oti.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe M, Bellamy C, Baranoski M, Wieland M, O'Connell MJ, Benedict P, Davidson L, Buchanan J, Sells D. A peer-support, group intervention to reduce substance use and criminality among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:955–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson Jeremy, Staff experience and patient outcomes: What do we know? A report commissioned by NHS Employers on behalf of NHS England. July 2014. (5). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell Martin, Dawson Jeremy, Topakas Anna, Durose Joan, Fewtrell Chris. Staff satisfaction and organisational performance:evidence from a longitudinal secondary analysis of the NHS staff survey and outcome data. HSDR 2014;2:ISSN 2050-4349. http://www.ihi.org/education/ihiopenschool/Pages/default.aspx [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjqir.u205967.w2458supp.pdf (162.1KB, pdf)