Abstract

Introduction

General practitioners have a key role in reducing cancer risk factors, screening for cancer and managing depression. Given the time-limited nature of consultations, a new and more time-efficient approach is needed which addresses multiple health needs simultaneously, and encourages patient self-management to address health risks. The aim of this cluster randomised controlled trial is to test the effectiveness of a patient feedback intervention in improving patient self-management of health needs related to smoking, risky alcohol consumption and underscreening for cancers at 1 month follow-up.

Methods and analysis

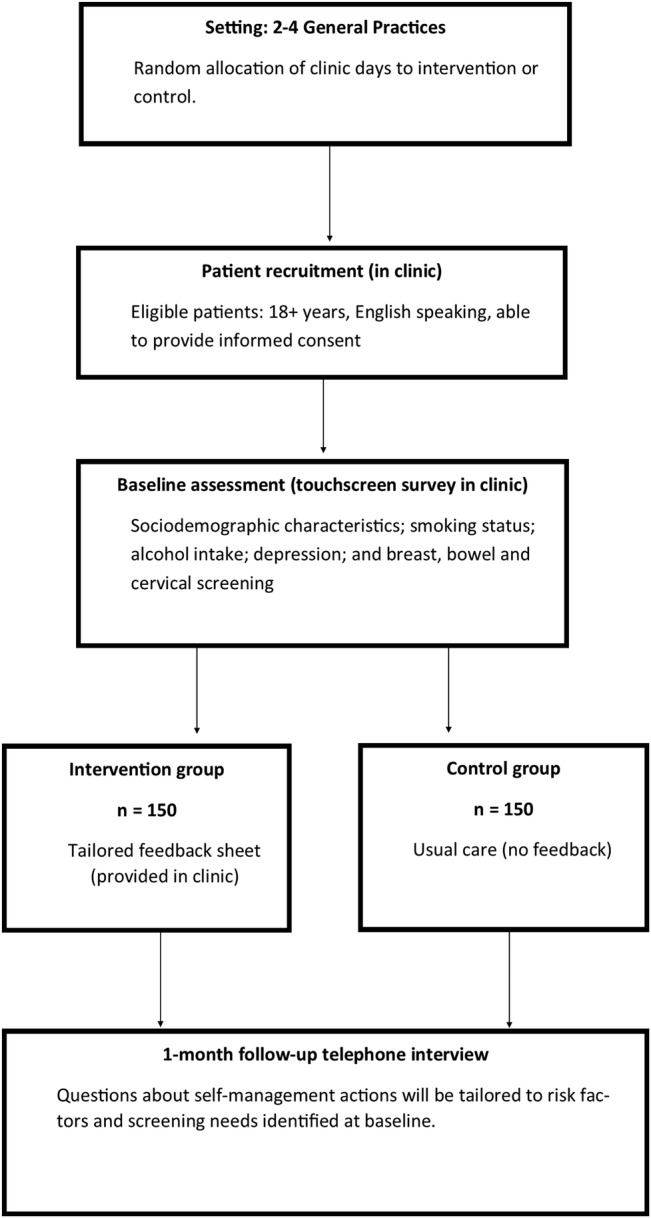

Adult general practice patients will be invited to participate in a baseline survey to assess cancer risk factors, screening needs and depression. A total of 360 participants identified by the baseline survey as having at least one health need (a self-reported cancer risk factor, underscreening for cancer, or an elevated depression score) will be randomised to an intervention or control group. Participants in the intervention group will receive tailored printed feedback summarising their identified health needs and recommended self-management actions to address these. All participants will be invited to complete a telephone interview 1 month following recruitment to assess self-management actions taken in relation to health needs identified in the baseline survey. Control group participants will receive tailored printed feedback on their identified health needs after their follow-up interview. A logistic regression model, with group allocation as the main predictor, will be used to assess the impact of the intervention on self-management actions.

Ethical considerations and dissemination

Participants identified as being at risk of depression will be advised to speak with their doctor. Results will be disseminated via publication in peer-reviewed journals. The study has been approved by the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee.

Trial registration number

Keywords: primary prevention, primary health care, self care, health behaviour, screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is one of the few to focus on an intervention for multiple health needs in primary care.

The study will use a randomised controlled trial design.

The study will use a touchscreen computer-based assessment of health risks and generate point-of-care tailored feedback for intervention participants.

The study will be based in several primary care practices.

Self-reported health needs are subject to bias such as social desirability and recall errors.

Introduction

Primary care is an appropriate setting for addressing health needs related to cancer prevention, early detection of cancer and depression.

General practitioners (GPs) play an important role in the provision of care for health needs related to the prevention and early detection of cancer. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)1 and the US Preventive Services Task Force2 recommend that GPs screen for risk factors associated with cancer, and there is evidence that GP intervention can be effective in reducing the prevalence of cancer-related risk factors such as smoking,3 risky alcohol consumption,4 poor diet5 and physical inactivity.6 GPs also play an important role in encouraging cancer screening by identifying those who are underscreened and offering appropriate referral for screening. Chances of survival are enhanced where cancer is detected at an early, localised stage,7–10 and Australian guidelines recommend regular mass screening for cancers including breast, colorectal and cervical cancer.1 GP endorsement of screening can significantly increase the likelihood of individuals engaging in screening tests.11 12 The RACGP also recommends routine screening for depression where staff-assisted depression care support is in place.1 For the remainder of this paper, the term ‘health need’ is used to refer to either a cancer-related health risk factor (such as smoking or risky alcohol consumption), underscreening for cancer or depression.

Evidence practice gaps in delivery of preventive care and cancer screening

Despite the importance of assessing modifiable cancer risk factors, a recent Australian study of 287 GPs indicated that for smoking, nutrition, alcohol and physical activity, only 37–46% of GPs report using guidelines.13 Sixty-eight per cent of GPs give verbal advice on smoking ‘very often’, but only 10% refer ‘very often’ for smoking management.13 Similarly, less than half give verbal advice for nutrition (48%), and only 28% and 27% ‘very often’ give advice on physical activity and alcohol consumption.13 Comparison between Australian studies14–18 conducted over the past three decades show that GPs' sensitivity in detection of smoking (56%, 66% and 63%) and risky alcohol consumption (28%, 40%, 26%) have not improved significantly over this time.19

Australian rates of participation in routine screening for cancer are also suboptimal. Less than 60% of eligible women have been screened according to guidelines for cervical and breast cancer;20 while only 37% of those approached for screening by the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program in 2013–2014 returned a sample.21 These figures suggest that there is a substantial opportunity to address health needs related to cancer screening and modifiable lifestyle risk factors in the primary care setting.

Why consider the management of depression?

It is well-established that certain risk factors and health conditions are likely to co-occur.22 Our data show that among 3559 Australian primary care patients, those with moderate and severe levels of alcohol misuse had higher rates of depression (18% and 26%, respectively), compared with those with no alcohol misuse (8%) or mild misuse (13%).23 Similarly, other studies have reported higher rates of depression among smokers.24 Changing complex behaviours such as smoking and risky alcohol consumption are likely to be difficult in the context of untreated depression.25–27 Therefore, when attempting to identify and intervene with such risk factors, it is important that depressive symptoms are also assessed and addressed.

Why identify and address multiple health needs simultaneously?

Several studies have shown that interventions delivered in the primary care setting are effective in promoting reduction of individual cancer risk factors. For example, physician advice is effective at promoting smoking cessation;28 brief GP counselling shows some effectiveness in reducing risky alcohol consumption;29 and educational strategies and GP endorsement can improve uptake of cancer screening.30 31 However, this approach does not reflect the common clinical scenario in which a patient presenting for care has multiple health needs that could potentially be addressed, and overlooks potential interactions or inter-relations between health needs. For example, providing support for depression may reduce the patient's depressive symptoms, but also has potential to reduce alcohol consumption.32 Delivering interventions which focus on increasing identification of each specific health need in isolation may also not be feasible due to time constraints within the consultation. Therefore, time-efficient approaches that consider how multiple health needs can be identified and addressed may be more efficient and sustainable. Indeed, some authors argue that multiple risk factor intervention should be the cornerstone of primary prevention.33 A limited number of studies have found small, but significant, effects on health behaviour outcomes from intervention addressing multiple health needs (ie, behavioural risk factors) in primary care.34 However, the majority of prior studies have focused on secondary rather than primary prevention.35 Therefore, there is a need to develop and test strategies for intervening with multiple health needs in the context of primary prevention.

Testing the impact of a low-intensity intervention to increase patient self-management of modifiable health needs

A key barrier to provision of care for modifiable health needs is lack of time to assess these needs.36 GP time pressure may mean that there is little time to opportunistically assess patients' needs and preferences for help, or to deliver interventions. Therefore, approaches which assist in identifying modifiable health needs and which support patient self-management of health risk factors may be helpful. Self-management refers to the tasks that patients perform, often on a day-to-day basis, to manage their health. This can include seeking professional help from their doctor, taking medications and implementing lifestyle changes. Informational interventions alone have been shown to increase rates of cancer screening.30 31 Provision of simple informational interventions may not always be sufficient on their own to change complex lifestyle behaviours such as smoking and risky alcohol consumption.37 However, such intervention may be effective in prompting self-management actions, including seeking GP advice, that lead to the uptake of more intensive interventions.

This study will test the impact of an e-health intervention in encouraging self-management of modifiable health needs. While there are a broader range of lifestyle risk factors such as poor nutrition and overweight which are associated with increased cancer risk, we chose to focus on risk factors which are more amenable to accurate reporting via self-report. For the purpose of this study, therefore, modifiable health needs include smoking, risky alcohol consumption, depression, and underscreening for breast, bowel and cervical cancer. The intervention will address key barriers such as GP identification of health needs and limited consultation time by assessing patient self-reported risk factors immediately prior to their general practice consultation, providing feedback to address knowledge and motivation barriers, and encouraging patients to seek advice from their GP.

Methods and analysis

Primary aim

To test the effectiveness of a patient feedback intervention in improving the proportion of patients who undertake one or more self-management actions for identified health needs related to smoking, risky alcohol consumption, and underscreening for bowel, breast and cervical cancer at 1 month follow-up.

Secondary aim

To examine the impact of depression scores on self-management behaviours for health needs identified at baseline (cancer screening needs, smoking or risky alcohol consumption).

Hypotheses

Compared with those allocated to the control group, the proportion of participants in the intervention group who report one or more self-management actions at 1 month follow-up will be 15% higher. Compared with those with lower depression scores, those with elevated depression scores will be less likely to engage in self-management behaviours.

Design and setting

The study will take place in 2–4 general practices in New South Wales, Australia. A parallel group 1:1 superiority cluster randomised controlled trial will be undertaken (figure 1). Each day that recruitment takes place within a participating practice will be randomly assigned to the intervention or control condition. Consenting patients will be allocated as a cluster to whichever condition is randomly assigned on that day. Randomisation will be conducted centrally using a computer-generated randomisation table. A separate randomisation list will be generated for each participating practice. Patients will be unaware of their group allocation on study entry. Outcomes will be assessed by telephonic interview at 4-week follow-up. Interviewers will be blind to the participant's allocation; however, due to the nature of the intervention blinding of participants is not possible. Results will be reported in line with the CONSORT statement. Patient recruitment will start in late October 2016 and will be completed by mid-2018.

Figure 1.

Study diagram.

Participants

Patients aged 18 or older, English speaking, who are presenting for a general practice appointment, able to provide informed consent and who have at least one of the following health needs will be eligible to participate: current smoker; consumes alcohol above levels recommended by health guidelines; underscreened for breast, bowel or cervical cancer; or elevated depression scores. Exclusion criteria: any patient who is considered too unwell to participate by practice staff will be excluded.

Procedure

When patients present for their primary care appointment, reception staff will assess their eligibility with respect to age, English proficiency and capacity to provide informed consent. Those who meet these criteria will be introduced to the research assistant who will provide study information and obtain written consent. The age and sex of non-consenters will be recorded to enable assessment of consent bias. Those who consent will be asked to complete a baseline survey to confirm eligibility based on the presence of one or more self-reported health needs. On receipt of consent, participants will be asked to provide their contact details to enable follow-up.

The survey will be administered on an internet connected touchscreen computer. The survey will assess smoking status, alcohol intake, depressive symptoms, as well as bowel, breast and cervical cancer screening behaviours. A computer-driven algorithm will be used to ensure that the questions are tailored to participants' age and sex (eg, only women will get mammography and cervical screening questions). Feasibility and acceptability of baseline data collection: Our prior study administered a similar health assessment to over 3000 patients from 12 general practices with an 86% consent rate. The administration of the assessment on a touchscreen tablet computer was highly acceptable, with more than 95% of the 596 patients reporting that these provide sufficient privacy and are easy to use.38

Intervention group

Participants in the intervention group will receive colour-printed tailored feedback on their survey results. The feedback will be automatically generated based on the participant's survey results. The feedback will highlight health needs, and provide a range of self-management actions or recommendations, such as any screening tests required, lifestyle changes to reduce alcohol consumption and/or cigarette smoking and the benefits associated with undertaking these actions, and details of organisations and helplines that can be accessed for further information about particular health risks. The feedback will be written at Flesch-Kincaid grade 7 level.

Usual care

Participants in the usual care condition will receive no feedback on their survey results at the time the survey is conducted. Usual care participants will instead receive written feedback by mail after the completion of the follow-up interview.

Follow-up data collection and participant retention

All participants eligible for the trial will participate in a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) 1 month later. The interview will assess any actions taken in relation to the health needs covered by the survey, and will be tailored to the participant's relevant health needs (ie, risk factors and screening tests required). Participants in the intervention group will also be asked about the acceptability of the feedback provided. Patients will indicate on the consent form their preferred day/time for contact. Patients that are unable to be contacted via phone will be sent a follow-up letter reminding them of the study and checking their contact details are correct. Participants will be able to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. Numbers and reasons for withdrawal will be recorded. Adverse events, if any, will be monitored and reported to the ethics committee, along with any changes to the protocol needed to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Training of recruitment and interview staff

A study manual has been developed that includes step-by-step instructions for implementing the study, and study documents such as information statements and consent forms. Recruitment and follow-up interview staff will undergo face-to-face training in study procedures in 2×2-hour training sessions. Simulated recruitment and follow-up interviews will be used to assess knowledge of the protocol. Follow-up interviewers will be blind to study allocation.

Measures

Baseline survey

The baseline survey will include the following items:

Sociodemographic characteristics: participants will be asked to self-report their age, sex, whether they are seeing their usual GP today, and if so, how many consultations they have had with that GP in the past 12 months; education level; whether or not they have healthcare concession card; and private health insurance status.

Screening status: (1) cervical cancer screening: women aged 18–69 will be asked whether or not they have had a pap test in the past 2 years; (2) breast cancer screening: women aged 50–69 will be asked whether they have had a mammogram in the past 2 years; and (3) bowel cancer screening: participants aged 50–75 years will be asked if they have had an faecal occult blood test (FOBT) in the past 2 years or a colonoscopy in the past 5 years. Recommended age groups and screening frequency are based on RACGP guidelines1 and will be used to identify those underscreened. Participants of the relevant age and gender will also be asked about any history of cervical or breast cancer or family history of bowel cancer, as these participants have different screening requirements.

Smoking status will be assessed by asking participants, ‘Which of the following best describes your smoking status?’. Response options include: I smoke daily, occasionally, used to, tried but not regularly, never tried. Those who report daily or occasional smoking will be classified as ‘at risk’. The validity of self-reported smoking status is high compared with urinary or serum cotinine concentrations.39 40

Risky alcohol consumption will be assessed using a version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) that has been modified to reflect definitions of risky alcohol consumption in current guidelines.41 Based on National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines (2009), those who reported consuming, on average, more than two drinks on a typical day when they consume alcohol, or who reported that they consume four or more alcoholic drinks on any occasion, will be classified as ‘at risk’. The AUDIT-C demonstrates good sensitivity and specificity for the detection of risky alcohol use determined by standardised diagnostic interview or validated calendar methods.42 43

Depressed mood: the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)44 is a brief nine-item depression screening tool which has been widely used in primary care settings. Items are related to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV diagnostic criteria for major depression. Frequency of symptoms is rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Higher scores indicate more severe depression. A recent meta-analysis has shown that the tool has high specificity (80%) and sensitivity (92%) when used to screen and diagnose major depression.45 Those scoring ≥10 are considered to have an elevated depression score46 and will be classified as ‘at risk’.

Preferences for type of self-management help: intervention participants will also be presented with a list of self-management options for identified health needs related to smoking, risky alcohol consumption, cancer screening (bowel, breast and cervical) and depression. Intervention participants will also be asked which self-management options they would be willing to undertake. For example, for participants who are identified as smokers, options will include being referred to Quitline (a telephone-based smoking cessation intervention), talking to their doctor, nicotine patches, medication and avoiding situations in which they smoke, quitting ‘cold turkey’ and using online smoking cessation programmes. Participants can indicate their willingness to engage in each strategy via a yes/no response.

Follow-up survey

The primary outcome will be whether participants have undertaken any self-management actions in the past month to address any health needs identified at baseline. Participants will be asked whether they have undertaken self-management strategies within the past month for lifestyle risk factors, cancer screening behaviours or depression, depending on whether these needs were identified at baseline.

Cancer screening: (1) cervical cancer screening: Those who reported being underscreened for cervical cancer at baseline will be asked whether they have undertaken any of the following actions in the past month (yes/no): discussed having a pap test with your GP, had a pap test, booked an appointment to have a pap test within the next month; (2) breast cancer screening: those who reported being underscreened for breast cancer at baseline will be asked whether they have undertaken any of the following actions in the past month (yes/no): discussed mammography with your GP, had a mammogram, made an appointment to have a mammogram within the next month; (3) bowel cancer screening: those who reported being underscreened at baseline will be asked whether in the past month they have done any of the following (yes/no): discussed bowel cancer screening with your GP, had a FOBT, had a colonoscopy, booked an appointment for a colonoscopy in the next month, planned to take a FOBT in the next month.

Self-management of smoking: Those who reported smoking at baseline will be asked whether they have undertaken any of the following actions in the past month (yes/no): quit cold turkey, cut down on number of cigarettes smoked per day, contacted Quitline, asked GP for advice about quitting, taken nicotine replacement therapy, taken medication to reduce cravings, downloaded a support app such as MyQuitBuddy, avoided situations in which they usually smoke or ‘other, please specify’.

Self-management of risky alcohol intake: Those who reported consuming alcohol above National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) recommended levels will be asked whether they have done any of the following over the past month (yes/no): set drinking limits and stuck to them, drunk more slowly, chosen alcoholic drinks with lower alcohol content, drunk water or non-alcoholic drinks between alcoholic drinks, eaten food before or while having an alcoholic drink, discussed treatment options and/or ways to cut down my alcohol intake their GP or ‘other, please specify’.

Self-management of depressed mood: Those who reported depressed mood at baseline will be asked whether they have undertaken any of the following actions in the past month (yes/no): discussed emotional problems with your GP, contacted the Beyondblue Helpline, attended counselling for emotional problems, taken prescription medication for emotional problems, improved my sleep habits, exercised more regularly, reduced my alcohol intake.

Smoking status and alcohol intake will be reassessed using the same measures used at baseline. Depressed mood will be reassessed using the PHQ-9 for those who reported a baseline score of 10 or more.

Analysis and sample size

The age and sex of consenters and non-consenters will be compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the t-test or non-parametric equivalent for continuous variables. Descriptive statistics including frequencies, proportions, 95% CIs and means will be calculated to describe risk factor status and demographic characteristics of the sample. Analysis will follow the intention-to-treat principles. The primary method of dealing with missing data will be through multiple imputations under a missing at random assumption. The proportion of participants in each group who report one or more self-management actions at follow-up will be calculated. A logistic regression model, with group allocation as the main predictor of interest, will be used to assess the impact of the intervention on preventive care actions. Parameters will be estimated under a generalised estimating equation framework to allow for potential clustering of patients from the same day. Other potentially confounding demographic and clinical variables will be adjusted for in the regression model in a secondary analysis (these will be prespecified in a statistical analysis plan). We will conduct a sensitivity analysis for the treatment of missing data including an analysis under the assumption that the data are not missing at random using pattern mixture models. For the secondary aim of the study, a similar logistic regression model will be used to assess the effect of baseline depressive mood (as measured through the PHQ-9) on self-management symptoms at follow-up. A directed acyclic graph will be used to determine the confounding variables that need to be included in the model, and these will be initially selected for consideration based on content knowledge of the research team. A total of 360 participants will be recruited at baseline (180 per group). Allowing for 15% attrition at 1 month follow-up, this will give an effective sample of 150 per group. Assuming a recruitment rate of 7 patients per day and allowing an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.01 for patients from the same day, a sample of this size, recruited over 42 days (of which 21 are intervention days) will give 80% power to detect a 15% increase in the proportion of patients who report one or more self-management actions at the 5% significance level.

Ethics and dissemination

Data management

Baseline data completed by touchscreen computer will be automatically captured by the web software and exported using a comma-separated values file. At follow-up, interviewers will enter participant responses using the CATI software during the interview. A randomly selected subsample of interviews will be audio-recorded to enable quality assurance checks and double entry of data. All data will be analysed using SAS.

All survey data will be de-identified and stored on a University server. Electronic data will be kept in a password-protected file so that only key project staff will have access to it. Data will be retained for at least 7 years.

Ethical considerations

All those in the intervention group who have elevated depression scores will receive feedback as part of the interventions about possible sources of help for depression. Usual care participants who report depression scores of 15 or more at baseline will receive on-screen feedback about this and be advised to discuss with their doctor. Study information sheets will include information regarding mental health helplines, and participants will be advised to speak with their doctor if their participation raises any concerns. Any adverse events will be immediately reported to the ethics committee. Owing to the low-risk nature of the intervention, a data monitoring committee will not be required.

Dissemination plan

There are no restrictions on publication of results arising from this study and the funding body will have no input into the decision to publish. It is planned that results will be disseminated via presentations at conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals. All authors of publications arising from this study will meet BMJ authorship guidelines.

Footnotes

Contributors: MC and RS-F conceptualised the study. MC will oversee the study implementation, and RS-F and MC will contribute to interpretation of data and reporting. EM and JW will assist in study implementation, and contribute to interpretation of data and reporting. CO will be responsible for statistical analysis, will assist with interpretation and reporting. All authors have contributed to the drafting and approval of this protocol.

Funding: This research is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) fellowship with co-funding from the Cancer Institute of NSW (1073031). This manuscript was supported by a Strategic Research Partnership Grant from Cancer Council NSW to the Newcastle Cancer Control Collaborative (CSR11-02).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study has been obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. 9th edn East Melbourne, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services 2012: recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilberink SR, Jacobs JE, Bottema BJ et al. . Smoking cessation in patients with COPD in daily general practice (SMOCC): six months’ results. Prev Med 2005;41:822–7. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V et al. . Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:986 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartley L, Igbinedion E, Holmes J et al. . Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(6):CD009874 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillsdon M, Foster C, Thorogood M et al. . Interventions for promoting physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD003180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Cancer Network Colorectal Cancer Guidelines Revision Committee. Guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. Vol 71 Sydney: The Cancer Council Australia and Australian Cancer Network, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. BreastScreen Australia Monitoring Report 2008–2009. Cancer series no. 63. Cat. no. CAN 60 Canberra: AIHW, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cervical screening in Australia 2009–2010. Cancer series 67. Cat. no. CAN 63 Canberra: AIHW, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Bowel Cancer Screening Program monitoring report: phase 2, July 2008- June 2011 Canberra: AIHW, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munro A, Pavicic H, Leung Y et al. . The role of general practitioners in the continued success of the National Cervical Screening Program. Aust Fam Physician 2014;43:293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weller DP, Patnick J, McIntosh HM et al. . Uptake in cancer screening programmes. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:693–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70145-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amoroso C, Hobbs C, Harris MF. General practice capacity for behavioural risk factor management: a snap-shot of a needs assessment in Australia. Aust J Primary Health 2005;11:120–7. 10.1071/PY05030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickinson J, Wiggers J, Leeder S et al. . General practitioners’ detection of patients’ smoking status. Med J Aust 1989;150:420–2, 425–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reid A, Webb G, Hennrikus D et al. . Detection of patients with high alcohol intake by general practitioners. BMJ 1986;293:735–7. 10.1136/bmj.293.6549.735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heywood A, Ring I, Sansonfisher R et al. . Screening for cardiovascular-disease and risk reduction counseling behaviors of general practitioners. Prev Med 1994;23:292–301. 10.1006/pmed.1994.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul C, Yoong SL, Sanson-Fisher R et al. . Under the radar: a cross-sectional study of the challenge of identifying at-risk alcohol consumption in the general practice setting. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:74 10.1186/1471-2296-15-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant J, Carey M, Sanson-Fisher R et al. . Missed opportunities: general practitioner identification of their patients’ smoking status. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:8 10.1186/s12875-015-0228-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant J, Yoong SL, Sanson-Fisher R et al. . Is identification of smoking, risky alcohol consumption and overweight and obesity by general practitioners improving? A comparison over time. Fam Pract 2015;32:664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer screening programs in Australia 2016. http://www.aihw.gov.au/cancer/screening/ (accessed 28 Sep 2016).

- 21.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Bowel cancer screening 2016. http://www.aihw.gov.au/cancer/screening/bowel/ (accessed 28 Sep 2016).

- 22.Fine LJ, Philogene GS, Gramling R et al. . Prevalence of multiple chronic disease risk factors: 2001 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Prev Med 2004;27:18–24. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobden B, Bryant J, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. doi: 10.1071/PY16076. Do rates of depression vary by level of alcohol misuse in Australian general practice? Aust J Primary Health. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendelsohn C. Smoking and depression: a review. Aust Fam Physician 2012;41:304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aubin HJ, Tilikete S, Barrucand D. Depression and smoking. Encephale 1996;22:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR et al. . The effect of depression on return to drinking: a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:259–65. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hymowitz N, Sexton M, Ockene J et al. . Baseline factors associated with smoking cessation and relapse. Prev Med 1991;20:590–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(2):CD000165 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F et al. . The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2009;28:301–23. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonfill X, Marzo M, Pladevall M et al. . Strategies for increasing the participation of women in community breast cancer screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(1):CD002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everett T, Bryant A, Griffin MF et al. . Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(5):CD002834 10.1002/14651858.CD002834.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker AL, Kavanagh DJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ et al. . Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: short-term outcome. Addiction 2010;105:87–99. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebrahim S, Taylor F, Ward K et al. . Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(1):CD001561 10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J, Planning Committee of the Addressing Multiple Behavioral Risk Factors in Primary Care Project. Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med 2004;27(2 Suppl):61–79. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prochaska JJ, Spring B, Nigg CR. Multiple health behavior change research: an introduction and overview. Prev Med 2008;46:181–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ampt AJ, Amoroso C, Harris MF et al. . Attitudes, norms and controls influencing lifestyle risk factor management in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:59 10.1186/1471-2296-10-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jepson RG, Harris FM, Platt S et al. . The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2010;10:538 10.1186/1471-2458-10-538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul CL, Carey M, Yoong SL et al. . Access to chronic disease care in the general practice setting: the acceptability of implementing systematic waiting room screening using computer-based patient-reported risk status. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:e620–6. 10.3399/bjgp13X671605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vartiainen E, Seppälä T, Lillsunde P et al. . Validation of self reported smoking by serum cotinine measurement in a community-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:167–70. 10.1136/jech.56.3.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong SL, Shields M, Leatherdale S et al. . Assessment of validity of self-reported smoking status. Health Rep 2012;23:D1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradley K, DeBenedetti A, Volk R et al. . AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31:1208–17. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith P, Schmidt S, Allensworth-Davies D et al. . Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:783–8. 10.1007/s11606-009-0928-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32:509–15. 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S et al. . Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1596–602. 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]