Abstract

Introduction

There are concerns that the use of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) in patients with brain injury may potentially elevate intracranial pressure (ICP). However, the transmission of PEEP into the thoracic cavity depends on the properties of the lungs and the chest wall. When chest wall elastance is high, PEEP can significantly increase pleural pressure. In the present study, we investigate the different effects of PEEP on the pleural pressure and ICP in different respiratory mechanics.

Methods and analysis

This study is a prospective, single-centre, physiological study in patients with severe brain injury. Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome with ventricular drainage will be enrolled. An oesophageal balloon catheter will be inserted to measure oesophageal pressure. Patients will be sedated and paralysed; airway pressure and oesophageal pressure will be measured during end-inspiratory occlusion and end-expiratory occlusion. Elastance of the chest wall, the lungs and the respiratory system will be calculated at PEEP levels of 5, 10 and 15 cm H2O. We will classify each patient based on the maximal ΔICP/ΔPEEP being above or below the median for the study population. 2 groups will thus be compared.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol and consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fujian Provincial Hospital. Study findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

NCT02670733; pre-results.

Keywords: Oesophageal pressure, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Positive end-expiration pressure, Intracranial pressure

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Oesophageal pressure will be measured in this study and thereby we will be able to differentiate the possible contributions of the lungs and the chest wall to the influence of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) on intracranial pressure (ICP).

Change of lung volume will be measured to clarify its contribution to ICP response.

The main limitation of this study is the absence of widely accepted thresholds to identify the responsiveness of ICP to increased PEEP, and we therefore arbitrarily divided patients into two groups using the median of the study population.

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is characterised by severe hypoxaemia and alterations in lung function, is common in critically ill patients. Numerous authors have reported that a significant portion of patients with brain injury can develop pulmonary complications, including ARDS and neurogenic pulmonary oedema.1–6 Ventilation strategies to protect the lungs should be applied in patients with ARDS.7 The mainstays of lung-protective ventilation strategies are to (1) limit tidal volume and driving pressure; (2) limit end-inspiratory plateau pressure (Pplat); and (3) provide adequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to keep the lungs open and prevent alveolar collapse.

There are concerns that the use of PEEP for the treatment of pulmonary complications in patients with brain injury could elevate intracranial pressure (ICP) and deteriorate neurological status. Both respiratory system elastance and ventricular compliance are thought to contribute to the elevation of ICP when PEEP increases.8–11 In theory, PEEP may increase ICP by increasing pleural pressure and diminishing venous return. However, the transmission of PEEP into the thoracic cavity depends on the properties of the lungs and chest wall. An experimental study conducted by Chapin et al12 showed that when chest wall elastance is high, PEEP can significantly increase pleural pressure, whereas high lung elastance can minimise airway pressure transmission. Lung elastance is generally recognised to increase in patients with ARDS due to extensive alveolar collapse. However, it has been reported that the chest wall elastance ratio (the ratio between the elastance of the chest wall and the respiratory system) may vary from 0.2 to 0.8.13 Therefore, it is important to distinguish between the elastance of the chest wall and the lungs when investigating the effects of PEEP on ICP.

We hypothesise that PEEP has greater influence on ICP in patients with higher chest wall elastance ratio (eg, the lung elastance is low and/or the chest wall elastance is high). To test the hypothesis, we need to measure the airway pressure and pleural pressure to calculate the elastance of the lung and the chest wall. However, pleural pressure is difficult to measure in clinical situations, and oesophageal pressure (Pes) is considered a surrogate of pleural pressure.14 15 In the present study, we will investigate the effects of PEEP on pleural pressure and ICP by measuring Pes.

Methods

Study design overview

The present study is a prospective, single-centre, physiological study in patients with severe brain injury.

Study setting and population

The study setting is the surgical intensive care unit (SICU; 22 beds), at Fujian Provincial Hospital (2500 beds), Fujian Provincial Clinical College of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China.

All patients admitted to the SICU will be consecutively screened for study eligibility.

Inclusion criteria are as follows:

Aged 18 years or above;

Glasgow Coma Score ≤8;

Ventricular ICP monitor placement for ICP monitoring and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage;

Need for mechanical ventilation with PEEP;

ARDS diagnosis according to the Berlin definition.7

Exclusion criteria are as follows:

Haemodynamic instability requiring more than 10 μg/kg/min dopamine or more than 0.5 μg/kg/min norepinephrine;10

ICP >25 mm Hg;

Decompressive craniectomy was performed;

Oesophageal varices;

History of oesophageal or gastric surgery;

Evidence of active air leak from the lung, including bronchopleural fistula, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum or existing chest tube;

History of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Baseline data collection

After enrolment, the following baseline data will be collected:

Demographic data: age, gender, height and predicted body weight, which is calculated as 50+0.91×(centimetres of height−152.4) for men and 45.5+0.91×(centimetres of height−152.4) for women.16

Clinical data: primary diagnosis, type of brain injury (traumatic brain injury, stroke or postoperation for brain tumour), type of brain lesion (bilateral or unilateral), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score at the time of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) on the day of enrolment, and duration of mechanical ventilation prior to enrolment.

Mechanical ventilation and blood gas at baseline: PEEP, fraction of inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2), partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2), PaO2/FiO2 (P/F ratio), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and pH.

Baseline ICP and haemodynamic parameters: heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), central venous pressure (CVP) and CVP change during the passive leg raising test.

Ventricular compliance measurement

ICP will be measured with a ventricular ICP monitor (Codman, Johnson & Johnson, Raynham, Massachusetts, USA). To measure ventricular compliance, 2 mL of CSF will be drained, and the ICP value before and after CSF drainage will be recorded. Ventricular compliance will be calculated as follows:

|

1 |

Placement of oesophageal balloon catheter

We will use the SmartCath-G adult nasogastric tube with an oesophageal balloon (7003300, CareFusion Co, Yorba Linda, California, USA) in this study. Patients will remain in a supine position with the head of the bed elevated to 30° during the study period. After anaesthetising the nose and oropharynx with 10% lidocaine spray, the oesophageal balloon catheter will be inserted through the nostril to a depth of 60 cm. The intragastric position of the distal part of the catheter will be confirmed by aspiration of gastric juice and auscultation of air insufflations into the stomach. After confirmation of the catheter position, the balloon will be inflated with 1.5 mL of air,17 18 and the proximal part of the catheter will be connected to the pressure transducer. Subsequently, the catheter will be slowly withdrawn, and the dynamic occlusion test will be performed.19 An end-expiratory occlusion will be performed until three to five spontaneous inspiratory efforts are made against the end-expiratory occlusion. The ratio of the change in Pes to the change in airway pressure (ΔPes/ΔPaw) will be calculated. The catheter will be considered correctly positioned when the ΔPes/ΔPaw ratio during the occlusion test is in the range of 0.8–1.2.20–22 In paralysed patients, the occlusion test will be performed by applying manual compression on the rib cage during the end-expiratory occlusion.

Pressure measurements

Flow will be measured with a Fleisch pneumotachograph (Vitalograph, Lenexa, Kansas, USA) inserted between the Y-piece of the ventilator circuit and the endotracheal tube. The volume will be obtained by electrical integration of the flow signal. Airway pressure (Paw, located distal to the pneumotachograph) and Pes will be measured with two differential pressure transducers (KT 100D-2, Kleis TEK di Cosimo Micelli, Italy, range ±100 cm H2O). The Fleisch pneumotachograph and pressure transducers will be connected to an ICU-Lab Pressure Box (ICU Lab, KleisTEK Engineering, Bari, Italy) by 80 cm tube lines. The signals will be displayed continuously and saved (ICU-Laboratory 2.5 Software Package, ICU Laboratory, KleisTEK Engineering, Bari, Italy) on a laptop for further analysis at a sample rate of 200 Hz. The pressure transducer will be calibrated with a water column. The pneumotachograph will be calibrated with a 1 L calibration syringe (SN: 554–2266, Hans Rudolph, Shawnee, Kansas, USA).

Respiratory mechanics measurements

After placement of the oesophageal balloon catheter, patients will be sedated and paralysed via intravenous infusion of 5 mg of midazolam, 0.1 mg of fentanyl and 50 mg of rocuronium. Mechanical ventilation will be set at a volume control ventilation, constant flow, an inspiratory–expiratory ratio of 1:2 and a tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg of predicted body weight. The initial respiratory rate will be set at 20/min and will be adjusted to maintain the PaCO2 value at ∼35–40 mm Hg. PEEP will be adjusted to 5 cm H2O. The oxygenation goal will be maintained constant at a pulse oxygen saturation above 90% by adjusting the FiO2. After a 30 min stabilisation period, blood gas analysis will be performed. Mean Paw and Pes will also be recorded. An end-inspiratory occlusion and an end-expiratory occlusion will be performed, and plateau pressure (Pplat) and total PEEP (PEEPtot) will be recorded. Pes during end-inspiratory occlusion (Pes-ei) and end-expiratory occlusion (Pes-ee) will also be recorded. Expiratory tidal volume (Vte) will also be recorded, and the elastance of the lungs (El), the chest wall (Ecw) and the respiratory system (Ers) will be calculated as follows:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

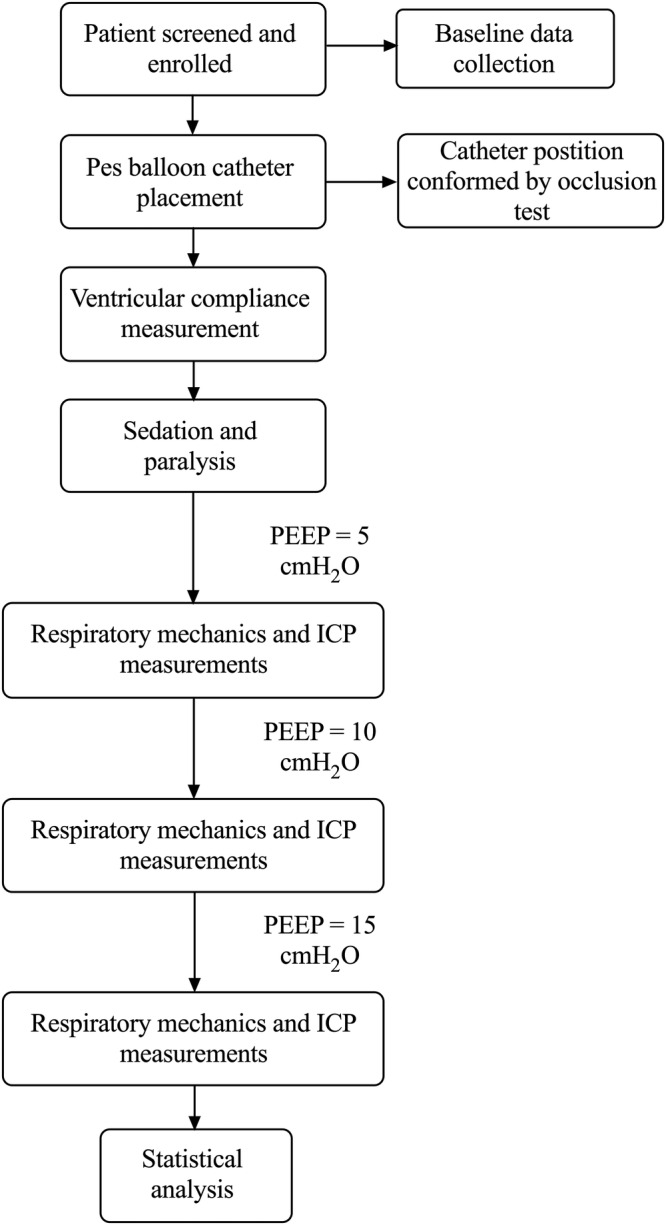

Thereafter, PEEP will be stepwise increased to 10 and 15 cm H2O. The measurements of ICP, ventricular compliance, haemodynamic status (HR, BP and CVP), blood gas analysis and respiratory mechanics will be repeated at these two PEEP levels. Changes in end-expiratory lung volume (ΔEELV) will also be measured, which is determined as the cumulative difference between inspiratory and expiratory tidal volumes, during the first 30 breaths following a change in PEEP level, with a systematic difference (namely VT offset) corrected.23–25

A flow chart of the study procedure is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study procedure. ICP, intracranial pressure; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Adverse event management and emergency termination of the study

Patients will be closely monitored during the study period. Taking into account the potential adverse effects of PEEP, emergency interventions will be provided when the following occur:

Abrupt increase of ICP >25 mm Hg and/or decrease of cerebral perfusion pressure <50 mm Hg that persists for >2 min. A bolus of 125 mL mannitol infusion will be administered.

BP decrease to below 90/60 mm Hg or a systolic BP decrease of >40 mm Hg; 100 mL of crystalloid fluid infusion will be administered. The study will be continued if the patient is responsive to the interventions (BP increases); otherwise, the study will be terminated and further interventions for decreased BP will be provided.

The procedure will be stopped if ICP is too high or BP is too low when 15 cm H2O PEEP is applied. The data obtained at 5 and 10 cm H2O PEEP will be collected.

Study end points

The primary end point is the influence of PEEP on ICP. There are two PEEP increases during the study procedure as follows: from 5 to 10 cm H2O and from 10 to 15 cm H2O. We will calculate ΔICP/ΔPEEP to standardise the influence of PEEP on ICP during the increase of PEEP for each step.

Secondary end points include the identification of possible contributors (see Statistical analysis section for detail) to the effects of PEEP on ICP and the investigation of the influence of PEEP on haemodynamic parameters, including CVP, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and cerebral perfusion pressure.

Statistical analysis

We will classify each patient into one of two groups according to the median value of ΔICP/ΔPEEP in the overall study population. The two groups will consist of patients with ICP responsiveness below the median value and ICP responsiveness above the median value. Since there will be two ΔICP/ΔPEEP values in one patient (except those who are intolerant to 15 cm H2O PEEP), the higher one will be used to determine the grouping.

Categorical variables will be presented as numbers and percentages and analysed by the χ2 test. Continuous variables will be tested for normal distribution and presented as the mean and SD or median and IQR as appropriate. Comparisons of continuous variables will be performed using Student's t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Wilcoxon signed-rank test will be performed to compare the difference of ΔICP/ΔPEEP between the two PEEP increases. Possible confounders of ICP responsiveness to PEEP including demographic data, type of brain injury (traumatic brain injury, stroke, postoperation for brain tumour), type of brain lesion (bilateral or unilateral), change in mean arterial pressure, ventricular compliance, respiratory mechanics (elastance of the lung, the chest wall and the respiratory system, ΔEELV, chest wall elastance ratio and change of elastance) and changes of PaO2 and PaCO2 will be collected in this study. First, univariate analysis will be performed. Thereafter, a multivariate logistic regression analysis will be performed using forward procedures with factors demonstrating p<0.20 in univariate analysis. All tests of significance will be at the 5% significance level and will be two-sided. Analyses will be performed with SPSS V.19.0 (IBM Corporation).

Sample size calculation

Prospective sample size calculations are performed using G*Power Software (sample size calculating software package provided by the G*Power Team, Germany, downloaded from http://www.gpower.hhu.de/en.html). We will need to study 30 participants to be able to reject the null hypothesis so that the means of chest wall elastance ratio of the two groups are equal with a probability (power) of 0.8. The type I error probability with testing this null hypothesis is 0.05.

Trial registration, ethical aspects and informed consent

The study was registered on 26 January 2016, at ClinicalTrials.org (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02670733).

After patients' eligibility for the study is confirmed, the study coordinator will be introduced to the patients' families. The ICU physician will emphasise the credentials of the study coordinator and communicate that this person will discuss a research programme for which the patient is qualified to participate. Every relevant aspect of the project will be described. The study coordinator will stop by frequently, ask if there are any questions, and request that the family repeat in their own words what is being discussed to ensure that the family understands the study. The study coordinator will be especially careful to assure the family that they are free to decline consent without consequences and that they can withdraw consent at any time without any impact on treatment. Family members will be provided with contact information of the study coordinator, the local co-investigator and the local Ethical Committee. Written consent will be obtained in the presence of a witness.

Dissemination plan

Results of the trial will be submitted to an international peer-reviewed journal. The results will also be presented at national and international conferences relevant to the subject fields.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that PEEP exerts no significant effects on cerebral haemodynamics in patients with high respiratory system elastance.10 However, elastance of the chest wall and the lungs were not distinguished in that previous study. In another study that examined chest wall and lung compliance, the authors did not investigate the effects of increased PEEP on ICP.12 In the present study, we aim to investigate the effects of PEEP on pleural pressure and ICP by measuring Pes.

Respiratory mechanics may change when PEEP is adjusted to a higher level. EELV can also increase with an increase of PEEP, as a result of recruitment of non-aerated lung units and distension of already aerated alveoli. Moreover, PaO2 and PaCO2 can also change with PEEP adjustments. All these may contribute to the influence of PEEP on ICP. Therefore, we will measure the respiratory mechanics, ΔEELV and blood gas to determine the possible contributors.

We will classify each patient with a high or low responsiveness of ICP to increased PEEP based on whether the ΔICP/ΔPEEP is above or below the median for the study population. Since there is no widely accepted threshold to identify the responsiveness of ICP to increased PEEP, the division of patients into two groups is reasonable and enables us to compare differences between the two groups of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lauren W from American Journal Experts for language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: HC, R-GY and J-XZ participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. MX, Y-LY, KC, J-QX and Y-RZ participated in the design of the study. All authors edited the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospital (ZYLX201502, DFL20150502).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol and consent forms were approved on 30 September 2015, by the Institutional Review Board of Fujian Provincial Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pelosi P, Severgnini P, Chiaranda M. An integrated approach to prevent and treat respiratory failure in brain-injured patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 2005;11:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland MC, Mackersie RC, Morabito D et al. The development of acute lung injury is associated with worse neurologic outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 2003;55:106–11. 10.1097/01.TA.0000071620.27375.BE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn JM, Caldwell EC, Deem S et al. Acute lung injury in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Crit Care Med 2006;34:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quilez ME, Lopez-Aguilar J, Blanch L. Organ crosstalk during acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18:23–8. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834ef3ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascia L. Acute lung injury in patients with severe brain injury: a double hit model. Neurocrit Care 2009;11:417–26. 10.1007/s12028-009-9242-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theodore J, Robin ED. Pathogenesis of neurogenic pulmonary oedema. Lancet 1975;2:749–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 2012;307:2526–33. 10.1001/jama.2012.5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyquist P, Stevens RD, Mirski MA. Neurologic injury and mechanical ventilation. Neurocrit Care 2008;9:400–8. 10.1007/s12028-008-9130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang WT, Nyquist PA. Strategies for the use of mechanical ventilation in the neurologic intensive care unit. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2013;24:407–16. 10.1016/j.nec.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caricato A, Conti G, Della Corte F et al. Effects of PEEP on the intracranial system of patients with head injury and subarachnoid hemorrhage: the role of respiratory system compliance. J Trauma 2005;58:571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burchiel KJ, Steege TD, Wyler AR. Intracranial pressure changes in brain-injured patients requiring positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation. Neurosurgery 1981;8:443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapin JC, Downs JB, Douglas ME et al. Lung expansion, airway pressure transmission, and positive end-expiratory pressure. Arch Surg 1979;114:1193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Carlesso E et al. Bench-to-bedside review: chest wall elastance in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit Care 2004;8:350–5. 10.1186/cc2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akoumianaki E, Maggiore SM, Valenza F et al. The application of esophageal pressure measurement in patients with respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:520–31. 10.1164/rccm.201312-2193CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brochard L. Measurement of esophageal pressure at bedside: pros and cons. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014;20:39–46. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devine BJ. Gentamicin therapy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1974;8:650–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mojoli F, Chiumello D, Pozzi M et al. Esophageal pressure measurements under different conditions of intrathoracic pressure. An in vitro study of second generation balloon catheters. Minerva Anestesiol 2015;81:855–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walterspacher S, Isaak L, Guttmann J et al. Assessing respiratory function depends on mechanical characteristics of balloon catheters. Respir Care 2014;59:1345–52. 10.4187/respcare.02974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baydur A, Behrakis PK, Zin WA et al. A simple method for assessing the validity of the esophageal balloon technique. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;126:788–91. 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.5.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgs BD, Behrakis PK, Bevan DR et al. Measurement of pleural pressure with esophageal balloon in anesthetized humans. Anesthesiology 1983;59:340–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milner AD, Saunders RA, Hopkin LE. Relationship of intra-oesophageal pressure to mouth pressure during the measurement of thoracic gas volume in the newborn. Biol Neonate 1978;33:314–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanteri CJ, Kano S, Sly PD. Validation of esophageal pressure occlusion test after paralysis. Pediatr Pulmonol 1994;17:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grivans C, Lundin S, Stenqvist O et al. Positive end-expiratory pressure-induced changes in end-expiratory lung volume measured by spirometry and electric impedance tomography. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011;55:1068–77. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garnero A, Tuxen D, Corno G et al. Dynamics of end expiratory lung volume after changing positive end-expiratory pressure in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit Care 2015;19:340 10.1186/s13054-015-1044-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl CA, Möller K, Schumann S et al. Dynamic versus static respiratory mechanics in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2090–8. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227220.67613.0D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]