Abstract

Landbirds undertaking within-continent migrations have the possibility to stop en route, but most long-distance migrants must also undertake large non-stop sea crossings, the length of which can vary greatly. For shorebirds migrating from Iceland to West Africa, the shortest route would involve one of the longest continuous sea crossings while alternative, mostly overland, routes are available. Using geolocators to track the migration of Icelandic whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus), we show that they can complete a round-trip of 11,000 km making two non-stop sea crossings and flying at speeds of up to 24 m s−1; the fastest recorded for shorebirds flying over the ocean. Although wind support could reduce flight energetic costs, whimbrels faced headwinds up to twice their ground speed, indicating that unfavourable and potentially fatal weather conditions are not uncommon. Such apparently high risk migrations might be more common than previously thought, with potential fitness gains outweighing the costs.

Recent advances in tracking movements of individual birds are revolutionising our understanding of avian migration1,2. New tracking technologies (e.g. geolocators and PTT transmitters) have revealed migratory journeys in excess of 5000 km of active flight1,2,3, setting the endurance exercise record of any animal4. Ultra long-distance continuous migratory flights have been suggested to facilitate avoidance of predators, parasites and pathogens5, but such continuous exercise is also known to increase mortality risk4. Migratory landbirds typically avoid crossing large ecological barriers such as mountain-ranges, deserts and oceans6,7, often using routes over suitable habitats along which stopping to rest and refuel is possible, for example by following the edge of continental land-masses6. However, when detours from the shortest route considerably increase travel distance, energy or time, crossing ecological barriers may be beneficial1. Birds breeding at high latitudes are often those that undertake the longest non-stop flights, crossing oceans1,8,9,10, ice-caps11 and deserts2, but such long flights can incur high mortality risk due to exhaustion associated with prolonged unfavourable weather conditions6. Species migrating by flying long distances continuously over oceanic waters1,3,8,12 and land masses2 all undertake stop-overs during either both journeys2,3,8,12 or pre-nuptial migration only1,6. During pre-nuptial migration, the use of stop-over sites might allow gauging conditions closer to the Arctic and subarctic breeding grounds as arriving too early can also be disadvantageous if conditions are unsuitable upon arrival6. Additionally, by refuelling during migration, birds can restore body reserves thus increasing the likelihood of reaching the breeding grounds in good condition and at the right time6,13. Non-stop long distance flights over unsuitable habitats entail considerable survival risk as no sheltering options are available and future weather conditions in distant locations are impossible to predict14. Indeed the largest mortality events recorded on migration (5000–200 000 individuals15,16,17,18) refer to landbirds crossing large waterbodies and encountering adverse weather conditions6. However, favourable winds can also play a fundamental role in the crossing over large expanses of unsuitable habitat such as oceans6. Many species wait for tailwinds at coastal sites for several days before embarking on large sea crossings, departing only when wind subsidies are considerable6,14. If significant headwinds are encountered during oceanic flights, birds must endure substantially longer flight periods which can result in depletion of fat and muscles and exhaustion19. It is therefore expected that birds depart for long distance sea crossings with favourable tailwinds and that flight air speeds are as high as possible, independent of winds encountered en route, in order to reduce exposure to potentially adverse conditions.

Iceland hosts important populations of several migratory wader (or shorebird) species20 which winter in Europe and west Africa21,22. These species have to negotiate one of the longest continuous sea crossing of all Arctic and subarctic breeding landbirds6. Species migrating to west Africa (e.g. the Bijagós archipelago in Guinea-Bissau) could either undertake a non-stop oceanic flight (~5800 km) or, after an initial sea crossing (~800 km) to the UK, follow the continental land masses to the wintering grounds (~5200 km). Both alternatives result in similar distances and some Icelandic breeding waders are known to follow the coastline21, even those for which a single flight overwater is potentially feasible23. The extent to which either of these routes is used is not known and although the non-stop oceanic flight is potentially of higher risk, this will likely depend on wind conditions during migration. We deployed geolocator tags on Icelandic whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus islandicus Brehm, 1831), a species which is known to winter in West Africa22 to investigate (1) if non-stop flights over oceanic waters between Iceland and West Africa are undertaken during autumn and spring migration; (2) the level of wind support encountered en route and how this affects flight speed.

Results and Discussion

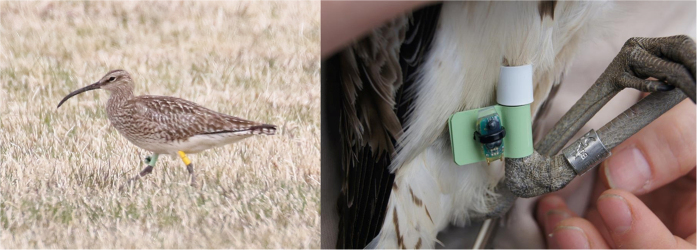

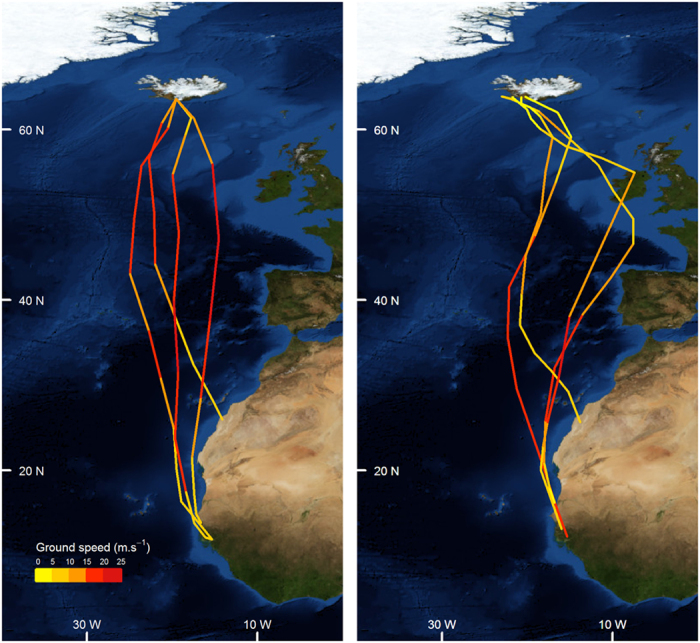

Ten adult breeding Icelandic whimbrels were tagged with geolocators in June 2012 (Fig. 1), seven were recorded on their territories in June 2013, of which four tags with data were retrieved. During the post-nuptial migration in autumn 2012, all four whimbrels flew non-stop to their wintering areas in west Africa (Fig. 2), covering distances of ~3900 to 5500 km in 5 days (Table 1) and, on occasion, achieving the fastest recorded speeds for terrestrial birds on long-distance flight over oceanic waters (up to 18–24 m s−1). During the return migration, two of these birds stopped for 11 (Male 2) and 15 days (Female 2), covering a total distance of ~10,500 and 11,000 km, respectively. However, the remaining female and male completed the return migration in another continuous flight (Fig. 2) for a total round trip of ~7800 (Female 1) and 11,000 (Male 1) km, respectively (Table 1). Completing such a long annual migration cycle in two long-distance flights is highly unusual for species where such studies have been undertaken. Only one other long-distance Arctic migrant wader, the Pacific Golden Plover (Pluvialis fulva), has been recorded undertaking such non-stop flights (ca. 9700 km total distance) between Alaska and Hawaii9. For this species however, no alternative route over coastal land masses is possible without considerably increasing flight distance.

Figure 1. Icelandic whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus islandicus) carrying a geolocator (left: photo by Tómas G. Gunnarsson) attached to a leg flag (right: photo by Camilo Carneiro).

Figure 2. Geotracked migratory routes of four Icelandic whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus islandicus) between breeding sites in Iceland and wintering areas in West Africa during post-nuptial/autumn (left) and pre-nuptial/spring (right) migration.

Track sections are coloured as a function of ground speed. All individuals flew non-stop in Autumn whilst two made a stop-over in the UK or Ireland in Spring (details in Table 1). Maps created using R 3.1.2 using packages ggplot2, ggmap, raster and RgoogleMaps33 (image data providers: US Dept. of State Geographer © 2016 Google) in WSG 48 coordinate reference system.

Table 1. Timings, distances and speed of total migration and non-stop flights by Icelandic whimbrels that flew direct to the winter grounds (all birds in Autumn) and that made a stop-over (Male 2 and Female 2) or a direct flight (Male 1 and Female 1) in the return migration (Spring).

| Migration | Atumn | Spring | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male 1 | Male 2 | Female 1 | Female 2 | Male 1 | Male 2 | Female 1 | Female 2 | |

| Onset of migration (departure) | 03-Aug | 06-Aug | 06-Aug | 03-Aug | 20-Apr | 22-Apr | 29-Apr | 23-Apr |

| End of migration (arrival) | 07-Aug | 10-Aug | 10-Aug | 07-Aug | 25-Apr | 10-May | 04-May | 14-May |

| Total duration (d) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 19 | 6 | 22 |

| Stopover time (d) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 15 |

| Total migration distance (km) | 5425 | 5171 | 3898 | 5535 | 5555 | 5364 | 3865 | 5560 |

| Total duration (h) | 107.8 | 107.9 | 78.9 | 120.0 | 121.2 | 444.1 | 127.3 | 540.6 |

| Total migration speed (km h−1) | 50.31 | 47.94 | 49.38 | 46.14 | 45.83 | 12.08 | 30.37 | 10.29 |

| Non-stop flights (over ground speed) | ||||||||

| Max speed (m s−1) | 24.18 | 18.60 | 17.93 | 21.91 | 19.71 | 21.29 | 13.45 | 18.19 |

| Min speed (m s−1) | 5.75 | 9.89 | 5.66 | 5.36 | 3.57 | 2.19 | 3.08 | 4.79 |

| Average (m s−1) | 15.55 | 14.38 | 13.32 | 14.35 | 13.87 | 8.24 | 9.09 | 9.63 |

| Sd | 6.84 | 3.00 | 4.19 | 6.42 | 5.10 | 5.40 | 3.17 | 4.25 |

| N | 7 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 11 | 15 |

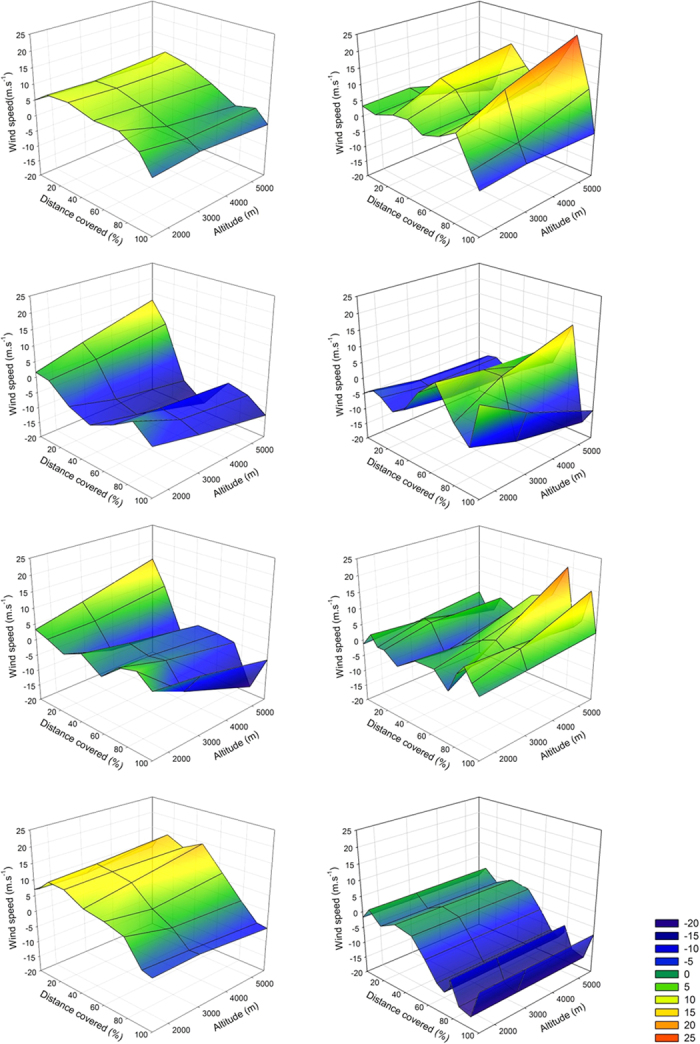

In order to assess how wind conditions encountered on these journeys varied, particularly for flights with and without stopovers, we quantified wind support at each position just prior to and during the migratory flight. All four whimbrels departed Iceland in favourable wind conditions (i.e. tailwinds), but all four arrived in West Africa having faced headwinds, mostly in the later part of the journey (Fig. 3). Conversely, only one individual departed from the winter grounds in favourable wind conditions (Male 1, the earliest to depart), while all others departed in headwinds of 1.3–4.8 m s−1, with one individual encountering headwinds for virtually the entire journey, including after stopping-over (Female 2, Fig. 3). A pre-nuptial migration strategy involving a stopover is likely safer regarding potentially unfavourable weather conditions encountered en route and upon arrival, but stopping to refuel will reduce overall migration speed. Indeed, and despite all tracked individuals departing the wintering grounds at similar times (22nd–29th of April), those flying non-stop arrived before those that undertook a stopover. This includes the last individual to depart which flew non-stop (Female 1) and arrived at the breeding grounds 6 to 10 days before the two individuals that made a stopover (of 11–15 days), thus overtaking its conspecifics23. The earlier arrival of the female and male that flew non-stop to Iceland could be advantageous if they capitalize by nesting early, as this is known to increase breeding success, particularly in Arctic and subarctic systems24. However, laying dates did not differ substantially between the individuals undertaking direct flights (20th–31st of May) or those that made a stopover (25th May–7th of June), suggesting that timing of breeding is constrained by other or additional factors, such as environmental conditions for nesting or timing of mate arrival (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 3. Variation in wind speed (m s−1) experienced during autumn (left column) and spring (right column) migratory flights of four Icelandic whimbrels.

Each row is one individual, following Table 1, from top to bottom: Male 1, Female 1, Male 2, Female 2. Negative wind values (blue) indicate headwind and positive values indicate tailwind. Wind was estimated for three flight altitudes: 1500, 3000 and 5500 m. Distance from departure location was converted into percentage for ease of interpretation.

The very fast ground speeds achieved by migrating whimbrels were influenced by the wind speeds encountered en route, particularly at altitudes of 1500 m (Table 2). Wind support at this altitude accounts for 4 to 36% of fastest speeds of each individual, with the highest wind assistance corresponding to the maximum recorded ground speed of 24.2 m s−1 (87 km h−1). Some individuals also reach very fasts speeds whilst facing headwinds which can be 2 to 40% of their ground speed, and in its most extreme case resulting in airspeed of 25.0 m s−1 (90 km h−1; Female 2). Average speeds for the entire continuous migratory flight are similar to those of other species crossing oceans (50–65 km h−1 5,8,9) which are also strongly influenced by wind speed en route5. By flying at high speeds and non-stop over open ocean these species reduce the time on migration and might be using an “airspace corridor” to avoid predators, parasites and pathogens5. But if wind conditions at distant locations along the route are unfavourable, such migratory strategy can result in mortality by exhaustion, even after arriving at destination (TGG, pers. observation).

Table 2. Results of GLMM of wind speed at three altitudes on ground speed of four Icelandic whimbrels tracked during migration between Iceland and West Africa.

| Estimate (SE) | df | t value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 12.11 (0.56) | 71 | 21.487 | <0.001 |

| Wind 1500 m | 0.51 (0.21) | 71 | 2.436 | 0.017 |

| Wind 3000 m | 0.16 (0.29) | 71 | −1.197 | 0.235 |

| Wind 5500 m | 0.70 (0.13) | 71 | 1.433 | 0.156 |

Our ability to track migration is providing new insights into the extraordinary capacity of birds to move extremely fast over very large distances, by continuously sustaining endurance exercise during several days. Wind support is crucial during such extreme journeys, but current predictions of changes in climatic patterns, specifically changes on regional scale wind patterns25, can potentially have a considerably disproportionate negative effect on those species that regularly undertake non-stop long distance flights over unsuitable habitats. Variation in migratory strategies within the same population will likely allow coping with potential changes, but predicting such responses requires an understanding on how these migration strategies can arise and are maintained. In addition, by linking different migratory strategies to associated fitness consequences will be key in our ability to anticipate demographic changes for migratory populations.

Methods

Bird tracking

Given Icelandic whimbrels previously established adult return rate (ca. 60–80%)26, in June 2012 we deployed 10 geolocators (Intigeo W65A9RJ, Migrate Technology) on breeding birds in South Iceland (63° 47N, 20° 12W). All individuals were caught with a nest trap (Moudry TR60; www.moudry.cz), ringed with metal and colour rings and measured to determine sex26. Seven of these birds were recorded breeding in the same location 12 months later, five of which (two females and three males) were re-captured and the geolocator collected. All of these individuals were from different pairs and the geolocator of one male was corrupted as a result of saltwater entering the device, leaving four individuals available for analysis. All animal handling and protocols were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations under licenses issued by Icelandic (Natural History Institute; license number 365) and International regulatory bodies (International Wader Study Group; license number 1235).

Positional data and flight speed

Light data from the geolocators were smoothed twice27 and used to estimate positions28 during migration (i.e. between Iceland and West Africa) using IntiProc (v. 1.03, Migrate Technology, Ltd.) and “GeoLight” package in R29, assuming a sun elevation angle of −6° based on in situ geolocator calibration prior to deployment. Total migration length, distance (great circle route) and speed were estimated between the last and first positions on land in the breeding areas (Iceland) or wintering areas (W Africa). As geolocator positions are only attained at a minimum of 12 hours intervals, flight speed (time taken to cover the distance between two sequential positions-in m s−1) was estimated for each 12 hour flight segment defined as two sequential positions between the first location outside the breeding, wintering or stop-over areas and the first location on land (at breeding, wintering or stop-over areas).

Wind support

Wind data at the location (±2.5 degrees) and time of each geolocator recorded position was extracted from NOAA using the dataset Reanalysis by NCEP30. Headwind or tailwind vector between sequential positions was interpolated for three altitudes (1500, 3000 and 5500 m) using function “NCEP.interp” from package RNCEP31. To test at which altitude wind speed had an effect on ground speed, we built a GLMM with individual as random factor to control the non-independence and DFs were calculated using the Satterthwaite approximation in package lmerTest. All analysis and calculations were performed in R 2.15.032.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Alves, J. A. et al. Very rapid long-distance sea crossing by a migratory bird. Sci. Rep. 6, 38154; doi: 10.1038/srep38154 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For support with fieldwork in Iceland and discussions, Graham Appleton, Jennifer Gill, Juan Carlos Illera and Sara Pardal. This work was funded by NERC, RANNIS - The Icelandic Research Fund (Grant of Excellence 130412-051) and FCT (individual grant to JAA: SFRH/BPD/91527/2012). NCEP Reanalysis data provided by the NOAA/OAR/ESRL PSD, Boulder, Colorado, USA, from their Web site at http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.A.A. conceived the study with input from T.G.G. and M.P.D., M.P.D. sourced the geolocators and B.K. and T.G.G. attained permissions. J.A.A., B.K., T.G.G. and V.M. developed fieldwork and J.A.A. & M.P.D. analysed the data. J.A.A. lead the writing with substantial contributions from M.P.D., B.K., V.M. and T.G.G.

References

- Battley P. F. et al. Contrasting extreme long-distance migration patterns in bar-tailed godwits Limosa lapponica. J. Avian Biol. 43, 21–32 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen R. H. G. et al. Great flights by great snipes: long and fast non-stop migration over benign habitats. Biol. Lett. 7, 833–5 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles L. J. et al. First results using light level geolocators to track Red Knots in the Western Hemisphere show rapid and long intercontinental flights and new details of migration pathways. Wader Study Gr. Bull. 117, 123–130 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Piersma T. Why marathon migrants get away with high metabolic ceilings: towards an ecology of physiological restraint. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 295–302 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill R. E. et al. Extreme endurance flights by landbirds crossing the Pacific Ocean: ecological corridor rather than barrier? Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 447–57 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton I. The Migration Ecology of Birds. (Academic Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam T. Bird Migration. (Cambridge University Press, 1990). [Google Scholar]

- Minton C. D. T. et al. Initial results from light level geolocator trials on Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres reveal unexpected migration route. Wader Study Gr. Bull. 117, 9–14. (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson O. W. et al. Tracking the migrations of Pacific Golden-Plovers (Pluvialis fulva) between Hawaii and Alaska: New insight on flight performance, breeding ground destinations, and nesting from birds carrying light level geolocators. Wader Study Gr. Bull. 118, 26–31 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Bairlein F. et al. Cross-hemisphere migration of a 25 g songbird. Biol. Lett. 8, 505–507 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. D., Glahder C. M. & Walsh A. J. Spring migration routes and timing of Greenland white-fronted geese-results from satellite telemetry. Oikos 103, 415–425 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Minton C. et al. New insights from geolocators deployed on waders in Australia. Wader Study Gr. Bull. 120, 37– 46 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam T. & Lindström Å. In Bird Migr. Physiol. Ecophysiol. (ed. Gwinner E.) 331–351 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg), doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74542-3_22 (1990). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamoun-Baranes J. et al. Stochastic atmospheric assistance and the use of emergency staging sites by migrants. Proc. Biol. Sci. 277, 1505–11 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P. Destruction of warblers on Padre Island, Texas. Wilson Bull. 68, 224–227 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- Webster F. S. The spring migration, April 1-May 31, 1974, South Texas region. Am. Birds 28, 822–825 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Jansson R. B. The spring migration, April 1-May 31, 1976, Western Great Lakes region. Am. Birds 30, 844–846 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam T. Findings of dead birds drifted ashore reveal catastrophic mortality among early spring migrants, especially Rooks Corvus frugilegus, over the southern Baltic sea. Anser 27, 181–218 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Pennycuick C. J. & Battley P. F. Burning the engine: a time-marching computation of fat and protein consumption in a 5420-km non-stop flight by great knots, Calidris tenuirostris. Oikos 103, 323–332 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson T. G. et al. Large-scale habitat associations of birds in lowland Iceland: Implications for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 128, 265–275 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Thorisson B., Eyjólfsson V., Gardarsson A., Albertsdóttir H. B. & Gunnarsson T. G. The non-breeding distribution of Icelandic Common Ringed Plovers. Wader Study Gr. Bullentin 119, 97–101 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson T. G. & Guðmundsson G. a. Migration and non-breeding distribution of Icelandic Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus islandicus as revealed by ringing recoveries. Wader Study 123, 44–48 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Alves J. A. et al. Overtaking on migration: does longer distance migration always incur a penalty? Oikos 121, 464–470 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson T. G., Gill J. A., Newton J., Potts P. M. & Sutherland W. J. Seasonal matching of habitat quality and fitness in a migratory bird. Proc. Biol. Sci. 272, 2319–23 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: fifth Assessment Report. (2014).

- Katrínardóttir B., Pálsson S., Gunnarsson T. G. & Sigurjónsdóttir H. Sexing Icelandic Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus islandicus with DNA and biometrics. Ringing Migr. 28, 43–46 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Pütz K. Spatial and temporal variability in the foraging areas of breeding king penguins. Condor 104, 528–538 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Dias M. P., Granadeiro J. P., Phillips R. A., Alonso H. & Catry P. Breaking the routine: individual Cory’s shearwaters shift winter destinations between hemispheres and across ocean basins. Proc. Biol. Sci. 278, 1786–93 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisovski S. & Hahn S. GeoLight-processing and analysing light-based geolocator data in R. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 1055–1059 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Kalnay E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-Year Reanalysis Project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–471 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Kemp M. U., Emiel van Loon E., Shamoun-Baranes J. & Bouten W. RNCEP: global weather and climate data at your fingertips. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 65–70 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. 1, 409 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Loecher M. & Ropkins K. RgoogleMaps and loa : Unleashing R Graphics Power on Map Tiles. J. Stat. Softw. 63, 1–18 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.