Abstract

Objective

Laparoscopy is increasingly being used as an alternative to open surgery in the treatment of patients with colon cancer. The study objective is to estimate the difference in hospital costs between laparoscopic and open colon cancer surgery.

Design

Population-based retrospective cohort study.

Settings

All acute hospitals of the National Health System in England.

Population

A total of 55 358 patients aged 30 and over with a primary diagnosis of colon cancer admitted for planned (elective) open or laparoscopic major resection between April 2006 and March 2013.

Primary outcomes

Inpatient hospital costs during index admission and after 30 and 90 days following the index admission.

Results

Propensity score matching was used to create comparable exposed and control groups. The hospital cost of an index admission was estimated to be £1933 (95% CI 1834 to 2027; p<0.01) lower among patients who underwent laparoscopic resection. After including the first unplanned readmission following index admission, laparoscopy was £2107 (95% CI 2000 to 2215; p<0.01) less expensive at 30 days and £2202 (95% CI 2092 to 2316; p<0.01) less expensive at 90 days. The difference in cost was explained by shorter hospital stay and lower readmission rates in patients undergoing minimal access surgery. The use of laparoscopic colon cancer surgery increased 4-fold between 2006 and 2012 resulting in a total cost saving in excess of £29.3 million for the National Health Service (NHS).

Conclusions

Laparoscopy is associated with lower hospital costs than open surgery in elective patients with colon cancer suitable for both interventions.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS, Hospital Costs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large study population including all patients with colon cancer undergoing an elective colectomy in National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England between 2006 and 2012.

Large administrative data set on costs reported by all NHS hospitals in England.

Our analysis is unable to provide direct control for some patient characteristics, such as cancer staging, obesity and the use of stomas. We provide indirect control for these factors by using propensity score matching and sensitivity analyses on restricted subsamples of low-risk patients.

Introduction

The introduction of laparoscopic surgery has resulted in significant improvements in outcomes for a range of surgical procedures including colon cancer resection. A number of studies show that laparoscopic colon cancer surgery is associated with better outcomes compared with open surgery both in terms of reduced mortality rates1 2 and other secondary outcomes such as shorter length of stay, reduced surgical complications, and reduced bleeding and pain.3–8 Laparoscopy has been increasingly used as an alternative to open resection for patients with colon cancer in England9 10 as well as in other countries.11 12 In England, the uptake of laparoscopy has been facilitated by increasing evidence of improved outcomes, effective training of surgeons in performing the procedure10 13 and the endorsement by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of laparoscopy as an oncologically acceptable alternative to open surgery.14

Evidence on the difference in the hospital costs of laparoscopy in comparison to open surgery is still limited. In England, the most recent Health Technology Assessment (HTA) study15 concluded that the hospital cost of a laparoscopic surgery was £265 (95% CI –3829 to 4405) greater than an open procedure in colorectal patients. However, this difference is not statistically significant and the authors recognise that evidence on costs was limited and based on heterogeneous studies. Similar evidence is found in a short-term cost analysis from the CLASICC randomised controlled trial (RCT): the difference was £268 (95% CI –689 to 1457) for a laparoscopic procedure and not statistically significant.16 Theatre costs were found to be higher for laparoscopy, while other hospital costs such as ward, hospital stay and complications were higher in the patients randomised to the open procedure.

The objective of this study is to produce new evidence on the difference in hospital costs between laparoscopic and open resections in patients with colon cancer. We use retrospective data on the whole population of patients with colon cancer undergoing an elective surgery between April 2006 and March 2013 in National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England. By examining a large population of patients, our analysis aims to reduce the problem of heterogeneity that might have affected estimates from previous studies. The HTA and a recent systematic literature review highlighted that heterogeneity in the examined studies affected the generalisability of the results of the meta-analysis of hospital costs.15 17

Finally, most of the existing evidence for England are based on patients admitted between 1996 and 2004 when only a restricted number of surgeons had experience in performing laparoscopic resections. In recent years, laparoscopic interventions have become more established technologies and account for more than half of all the elective surgery procedures performed on patients with colon cancer. The diffusion of laparoscopy is likely to have had an impact on costs as an increasing number of surgeons achieve greater experience in performing the new procedure thereby reducing operating time, patient length of stay and conversion rates.18 Therefore, new evidence on costs is needed to inform surgeons and hospital managers on the most efficient intervention and to support the efficient allocation of healthcare resources.

Methods

Data sources

Anonymised patient-level records were extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database.i HES is a hospital administrative database which routinely collects information on all admissions to NHS hospitals and a minority of private hospitals in England and has been described in detail elsewhere.19 Data are collected at the level of a consultant episode, that is, the time the patient spends under the care of a single consultant team. Data fields include patient primary diagnosis and comorbidities (up to 20 comorbidities), which are coded using the International Classification of Disease 10th revision (ICD-10), and medical treatments and procedures (up to 24 procedures are coded) which are coded using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures 4th revision (OPCS-4).20 Information on admission and discharge dates, health outcome at discharge and whether the admission was planned (elective), or unplanned (emergency), is also included in HES. A range of pertinent sociodemographic information is also available, including age, sex and deprivation score of area of residence.

Hospital admission costs were obtained from the National Schedule of Reference Costs (NSRC) 2012/2013. NHS hospitals are mandated to report the unit cost of each of the services delivered to their patients every year. To this end, medical treatment and procedures delivered during a consultant episode are grouped into homogeneous Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs) and costs are apportioned following guidelines produced by Public Health England.21 Hospitals report the average cost of regular length of stay patients and the extra cost of outlier length of stay patients for each HRG and type of admission. They also report the total number of bed days and consultant episodes by HRG and type of admission. Cost information on 2353 different HRGs is reported in the NSRC 2012/2013 and we matched these data to each year of HES data using the procedure described in the Costs section below.

This study followed Strengthening of Reporting Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.22

Patients

All patients aged 30 years and over who underwent elective colonic resection with a diagnosis of colon cancer (ICD-10 diagnosis ‘C18’) between April 2006 and March 2013 were included in the analysis, where the index admission length of stay did not exceed 90 days. We excluded admissions occurring 12 months after the first admission, that is, the index admission. The following OPCS codes were used to identify open procedures: H05/H29 (subtotal/total colectomy), H06 (extended right hemicolectomy), H07 (right hemicolectomy), H08 (transverse colectomy), H09 (left hemicolectomy), H10 (sigmoid colectomy) and H11 (other colectomy). A procedure was considered to be laparoscopic in the presence of any of the following additional codes: Y50.8, Y75.1 and Y75.2. Also, laparoscopic procedures converted to open were included in this group (Y71.4 and Y71.8).

Costs

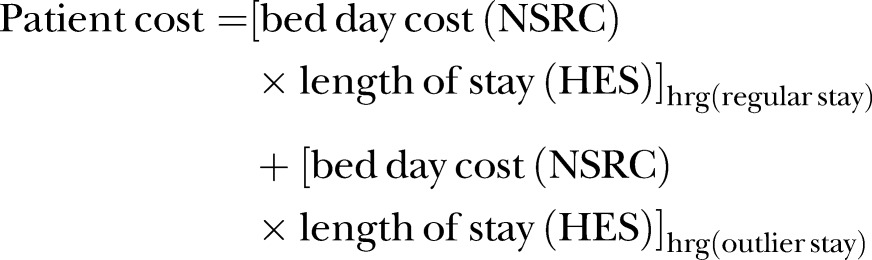

We used the hospital cost of each patient admission as the outcome variable in our analysis with costs estimated at 2012 prices. We obtained this variable by combining information reported in HES on patient admissions and information reported in the NSRC on HRG costs. The cost variable was calculated as follows:

First, we calculated the national average cost for each HRG as a weighted average of the HRG costs reported by every hospital. This reduced the scope for hospital errors in reporting the cost of their services. Second, we calculated the cost per bed day by using information reported on total activity and total bed days for each HRG and calculated these separately for regular and for outlier length of stay. Third, we matched the HRG bed day cost obtained from the NSRC to the corresponding HRG reported in HES. We used the patient length of stay reported in HES to construct our estimate of the admission cost for each patient in our sample as follows:

|

1 |

This method of costing inpatient care has been used previously.23–25 In the absence of a separate HRG for laparoscopic and open colectomy, the difference in theatre costs associated with the two procedures was estimated using a weighted average of the difference reported by two most recent RCTs on patients with colon cancer.16 26 The additional operating cost for laparoscopy amounted to £532 at 2012 prices.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure of this study was the hospital cost of laparoscopic versus open colectomy. Hospital costs were calculated for the initial admission and for the first of any unplanned readmissions occurring within 30 and 90 days after discharge. Secondary outcomes were 30-day in-hospital mortality and unplanned readmission rates at 30 and 90 days after discharge.

Laparoscopy rates and costs were also compared by operation subtype as part of the sensitivity analyses.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was undertaken using STATA V.13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). The χ2 tests were used to compare categorical variables. The estimates of the differences in cost between laparoscopic and open surgery were calculated using propensity score matching (PSM) of patient, area of residence and hospital characteristics. PSM allows us to generate a control group of open resection patients who are similar to patients undergoing a laparoscopic operation. PSM allows for any differences between the open and laparoscopic groups to be reduced by matching on the propensity score calculated from patient, area of residence and hospital characteristics. The potential confounders used to match patients were age, Charlson comorbidity index score, number of diagnoses, deprivation index (in quintiles) and year of procedure. In order to control for differences in the characteristics of the healthcare providers, fixed effects for the hospitals of patients' admission were included in the matching. A match of the 10 closest patients (neighbours) was undertaken. To prevent poor matches, a caliper was used which included only matched patients within 0.25 SDs of each other.27 PSM was undertaken on 20 238 who had a laparoscopic resection (exposed group) and 33 750 (unexposed group).

Ethics statement

We used fully anonymised and unidentifiable hospital administrative data from HES database.

Results

Descriptive statistics

In total, 55 358 elective colorectal resections were analysed over the 7-year study period. Table 1 compares the characteristics of patients who underwent laparoscopic and open surgery in the study sample. The laparoscopy group had a slightly lower proportion of patients with high Charlson scores and fewer diagnoses (p<0.01). Such differences noticeably reduce and are not statistically significant in the matched sample as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with colon cancer undergoing elective laparoscopic and open resections, 2006–2012

|

Before PS matching |

After PS matching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopy | Open | Laparoscopy | Open | |||

| Per cent | Per cent | p Value | Per cent | Per cent | p Value | |

| Age | ||||||

| 30–40 | 1.1 | 1.1 | <0.01 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.41 |

| 41–50 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.3 | ||

| 51–60 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.4 | ||

| 61–70 | 29.7 | 26.6 | 29.7 | 29.5 | ||

| 71–80 | 35.8 | 36.6 | 35.8 | 35.9 | ||

| 81+ | 20.7 | 21.6 | 19.7 | 20.0 | ||

| Weighted Charlson score | ||||||

| 2 | 57.5 | 51.8 | <0.01 | 56.5 | 56.9 | 0.92 |

| 3–4 | 24.7 | 24.6 | 24.9 | 24.3 | ||

| 5+ | 17.8 | 23.6 | 18.6 | 18.8 | ||

| Number of diagnoses | ||||||

| 1–2 | 25.1 | 24.5 | <0.01 | 25.1 | 25.3 | 0.56 |

| 3–4 | 30.9 | 30.2 | 31.0 | 30.6 | ||

| 5–6 | 22.2 | 22.3 | 22.2 | 22.0 | ||

| 7+ | 21.8 | 23.0 | 21.7 | 22.1 | ||

| Deprivation score | ||||||

| Least deprived | 18.5 | 20.9 | <0.01 | 18.6 | 18.5 | 0.30 |

| 2 | 19.8 | 20.1 | 19.8 | 19.4 | ||

| 3 | 19.8 | 20.1 | 19.9 | 19.7 | ||

| 4 | 20.5 | 19.7 | 20.4 | 20.6 | ||

| Most deprived | 21.4 | 19.2 | 21.3 | 21.8 | ||

| Female | 47.7 | 48.3 | <0.21 | 47.7 | 47.9 | 0.60 |

PS, propensity matching.

Trends over time

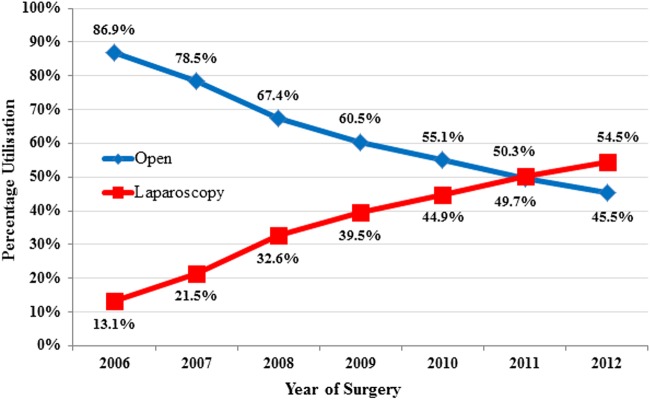

Figure 1 presents the proportion of colon cancer operations undertaken by the laparoscopic or open approach between April 2006 and March 2013. In 2006, only 13.1% of colectomies were laparoscopic. Over the next 7 years, a sharp increase in laparoscopic rates was observed. By 2012, 54.5% of patients in our study sample underwent laparoscopic colectomy. Trends in the use of laparoscopy across hospitals also changed over time (see online supplementary appendix figure A1).

Figure 1.

Shares of laparoscopic and open resections in patients with colon cancer undergoing elective surgery, 2006–2012.

bmjopen-2016-012977supp_figures.pdf (262.8KB, pdf)

Primary outcomes

Table 2 presents the unadjusted and adjusted differences in hospital costs and mean length of stay between laparoscopic and open resections in our study sample. Unadjusted comparisons show large differences in hospital costs and length of stay due to differences in the characteristics of the patients undergoing the two treatments. PSM allows us to adjust for these differences and remove their confounding effect on the examined outcomes.

Table 2.

Differences in hospital costs between laparoscopic and open resections in patients with colon cancer undergoing elective surgery, 2006–2012

| Unadjusted outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open | Laparoscopy | Difference | |||

| Cost of initial admission | £11 727 | £9215 | £2512 | ||

| Including 30-day readmission | £12 311 | £9604 | £2707 | ||

| Including 90-day readmission | £12 581 | £9761 | £2820 | ||

| Length of stay | 11.9 days | 8.5 days | 3.4 days | ||

| Adjusted outcomes | |||||

| Open | Laparoscopy | Difference | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Cost of initial admission | £11 145 | £9214 | £1933 | £1744 to £2122 | <0.01 |

| Including 30-day readmission | £11 710 | £9603 | £2107 | £1896 to £2315 | <0.01 |

| Including 90-day readmission | £11 964 | £9762 | £2202 | £1982 to £2420 | <0.01 |

| Length of stay | 11.0 days | 8.5 days | 2.5 days | 2.3–2.7 days | <0.01 |

After adjusting, the cost of a patient undergoing laparoscopic surgery was £1933 (95% CI 1744 to 2122, p<0.01) less at the index admission. With the inclusion of costs of first readmission at 30 and 90 days following initial discharge, this saving rose to £2107 (95% CI 1896 to 2315, p<0.01) and £2202 (95% CI 1982 to 2420, p<0.01), respectively. Length of stay was 2.5 days (95% CI 2.3 to 2.7, p<0.01) shorter for patients following laparoscopic surgery.

ORs from the logistic analyses are given in online supplementary appendix table A1. A figure illustrating the performance of PSM between the laparoscopy and open groups is given in online supplementary appendix figure A2.

bmjopen-2016-012977supp_tables.pdf (236KB, pdf)

Comparison of adjusted mortality and readmission rates

Table 3 gives the adjusted rates and ORs following PSM analysis for mortality and readmission. Laparoscopy was associated with a significantly lower mortality within 30 days of admission (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.75, p<0.01). There was also a significantly lower rate of readmission both within 30 days (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.96, p<0.01) and 90 days (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.93, p<0.01) of discharge, compared with open surgery.

Table 3.

Risk-adjusted mortality and hospital readmissions following laparoscopic and open resections in patients with colon cancer undergoing elective surgery, 2006–2012

| Open (%) | Laparoscopy (%) | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day in-hospital mortality | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.60 | 0.46 to 0.75 | <0.01 |

| 30-day unplanned readmission | 4.8 | 4.2 | 0.87 | 0.77 to 0.96 | <0.01 |

| 90-day unplanned readmission | 6.9 | 5.9 | 0.85 | 0.77 to 0.93 | <0.01 |

Cost to the NHS

Table 4 reports the annual total hospital cost of colon cancer resections in our study sample, including costs incurred from first unplanned readmission within 90 days of initial discharge. The third column reports total costs using the observed rate of laparoscopic procedures for the year studied, while the fourth column reports an estimate of the total cost had the rate of laparoscopy remained unchanged at 2006 levels. Between 2006 and 2012, the change in surgical practice that favoured the increasing use of laparoscopic surgery resulted in an estimated cost saving of £29.3 million for the NHS hospitals.

Table 4.

Estimated cost savings for colon cancer surgery (including 90-day unplanned readmission costs) due to the rise in laparoscopy rates since 2006

| Year | Laparoscopy rate | Costs: actual laparoscopy rate | Costs: fixed 2006 laparoscopy rate | Achieved savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (£ millions) | (£ millions) | (£ millions) | ||

| 2006 | 13.1% | 84.3 | 84.3 | 0.0 |

| 2007 | 21.5% | 86.5 | 87.8 | 1.3 |

| 2008 | 32.6% | 89.5 | 92.9 | 3.4 |

| 2009 | 39.6% | 89.1 | 93.8 | 4.7 |

| 2010 | 44.9% | 89.4 | 95.1 | 5.7 |

| 2011 | 50.3% | 91.3 | 98.2 | 6.9 |

| 2012 | 54.5% | 86.7 | 94.0 | 7.3 |

| 2006–2012 | − | 616.8 | 646.1 | 29.3 |

Sensitivity analyses

Among both laparoscopic and open surgery groups, the distribution in operation subtypes was broadly similar. The most common procedure in each group was extended right/right hemicolectomy followed by sigmoid colectomy (see online supplementary appendix table A2). Procedure subtypes were not included in the list of matching variables as they may not affect the allocation of patients to a laparoscopic or open intervention, and can be considered as part of the intervention.

Cost savings during the initial admission and first unplanned readmission within 90 days were found in all types of colectomy (see online supplementary appendix table A3). The greatest difference was observed for sigmoid colectomy (H10) where laparoscopy was associated with a saving of £2285 (95% CI 1800 to 2771, p<0.01).

Subanalysis of a restricted sample of patients with a length of stay of <30 days, and no more than a single consultant episode (see online supplementary appendix table A4). PSM analysis in this group of 47 483 patients showed smaller but still noticeable differences. After matching, the cost saving of laparoscopic surgery was £1593 (95% CI 1477 to 1709, p<0.01) compared with open surgery; the difference was £1737 (95% CI 1604 to 1871, p<0.01) with the inclusion of 30-day readmission costs and £1831 (95% CI 1604 to 1871, p<0.01) with 90-day readmission costs.

Subanalysis using 2012–2013 data only was also undertaken in order to reduce potential selection bias from early adopters that might have selected easier cases in early years (see online supplementary appendix table A5). Estimated differences in adjusted costs between the two procedures were very similar to those found in the main analysis.

Discussion

This study produces new evidence on the difference in hospital costs between elective laparoscopic and open resections in patients with colon cancer. We used retrospective data on the whole population of patients undergoing an elective surgery in NHS hospitals in England from April 2006 to March 2013. PSM was used to create two similar groups of patients undergoing the two treatments. We find evidence that laparoscopic surgery is the less expensive treatment and can result in savings of £1933 in hospital costs during the first admission or £2202 if including unplanned readmissions occurring within 90 days of discharge. Although laparoscopic surgery requires initial investments in equipment and training, these costs are more than compensated by savings from reduced hospital length of stay and reduced risk of readmissions.

Our study also supports evidence from previous studies that patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery have reduced mortality and readmission rates compared with open surgery.1 2 5 6 9 28 29

Our results are in line with recent evidence from international studies showing laparoscopy to be a less costly approach for patients with colon and colorectal cancer. Studies from Ireland, Canada and Australia have reported cost savings of €4591 (∼£3600),30 $3121 (∼£2062)31 and €2012 (∼£1578),32 respectively. These studies found that shorter hospital stay and lower postoperative costs were the major contributors to cost savings which offset the larger operative costs associated with laparoscopy when compared with open surgery. Finally, a recent study from the USA found similar evidence in patients without cancer undergoing a colectomy.33 In our PSM analysis, we find a shorter length of stay of 2.5 days for laparoscopic patients. A similar difference is reported in a number of RCTs.3 4 6 16 26

In England, the most recent evidence on costs comes from the 2006 HTA15 and the CLASICC trial16 and it is based on patients admitted between 1996 and 2004. Both studies report a small and non-statistically significant difference in hospital costs with large CIs; laparoscopy was the more expensive procedure with a difference of £265 (95% CI −3829 to 4405) in the former and £268 (95% CI −689 to 1457) in the latter. Heterogeneity in the study sample might explain the large CIs in the results of the cost analysis in the HTA and in a recent systematic literature review.12 Significant heterogeneity was found for operative time, intraoperative blood loss, duration of hospital length of stay, overall postoperative complications and cost of surgery in the short-term analysis. Moreover, the laparoscopic resection was a less common procedure at the time of the HTA and CLASICC trial and significant progress in performing this intervention are likely to have occurred in recent years as laparoscopy has become as prevalent as open surgery.

Study limitations

This study is based on a retrospective analysis of administrative data from HES. The study design does not allow us to control for a number of factors that are likely to influence patients' allocation to a laparoscopic or open intervention and potentially result in selection bias. The HES data do not include information on some patient characteristics that might make them unfit for laparoscopic surgery, such as obesity and multiple previous abdominal operations. The use of stomas has also not been factored into the analysis, which may influence length of stay and readmission rates. Finally, cancer staging is not reported and we are unable to stratify for this variable in our analysis. Larger or more advanced tumours may be selected for open surgery over laparoscopy and these may be associated with more extensive procedures with increased postoperative complications and costs.9 We use a number of techniques to mitigate potential selection bias from unreported patients' characteristics.

First, our analysis is restricted to elective admissions only as emergency presentation is more likely to capture advanced tumours in a screened population. A similar approach has been used in a number of earlier studies using HES data to compare the outcomes of laparoscopy and open resections in patients with colon cancer.2 7 9 10 20 29

Second, our study examines the difference in costs between the two procedures in 2006–2012 when laparoscopy reached a similar level of diffusion as open surgery reducing the scope for selection bias from early adopters. We use PSM techniques to create a similar sample of patients undergoing the two treatments in a large population of patients with colon cancer. Although PSM cannot assure the same level of randomisation as an RCT, the issue of patient selection should be less relevant in our study population as the prevalence of laparoscopy is similar to open resection in the examined years. PSM allows us to analyse retrospective data on a very large population of patients reducing the problem of heterogeneity and increasing the power of the statistical analysis and external validity of results. Finally, we are able to produce robust evidence at a fraction of the cost of an RCT.

Third, we conducted a number of sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings to potential sample selection bias. We examined a highly restricted sample of patients who had routine and uncomplicated elective admissions, and who are less likely to be frail and having comorbidities; differences in outcomes and cost savings are still present. We also repeated our analysis using 2012–2013 data only in order to reduce the scope for selection bias from early adopters who are likely to select easier cases as the prevalence of laparoscopic surgery moves from 13.1% in 2006–2007 to 54.5% in 2012–2013. We find very similar results suggesting that the differences in costs and outcomes are explained by laparoscopic surgery rather than selection bias from early adopters.

This study combines retrospective data on hospital admissions from HES with data on service costs from the NSRC creating a powerful tool of analysis. The validity of these data for cost analysis has been demonstrated elsewhere34 and the data have been successfully applied in a number of empirical investigations on the costs of care.23–25 However, NSRC data do not report the difference in theatre costs associated with the two procedures, which was estimated using a weighted average of the difference reported by two most recent RCTs on patients with colon cancer.16 26

Finally, this study focuses on direct hospital costs and does not consider the opportunity costs associated with the two interventions. On one hand, open resections are associated with shorter operating theatre time, which might offer the opportunity of performing more interventions per day. On the other hand, laparoscopic resections are associated with shorter postoperative length of stay and lower probability of a 90 days readmission, which might free up hospital beds and resources for treating other patients. Assessing opportunity costs is challenging as theatre time and hospital beds can be allocated to a number of alternative uses depending on the local demand for care and the local organisation of health services.

Conclusion

This study supports the adoption of laparoscopic surgery as a cost saving alternative to open surgery in patients with colon cancer suitable for both interventions. The adoption of laparoscopic surgery can lead to reduced hospital stay, morbidity and mortality in the treatment of colon cancer, which translate into cost savings for the health system.

Acknowledgments

The research is supported by Macmillan Cancer Support, Cancer Research UK, St Marks Foundations, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML, BW, AM and OF were involved in formulating the study hypothesis. ML had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. ML carried out the empirical analysis. ML, BW and AM prepared the first study draft; all authors contributed and approved the final version submitted.

Funding: The work is supported by a Macmillan Cancer Support Grant (ML, BW), Cancer Research UK and the National Institute for Health Research (AM), and the St Mark's Foundation (OF).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of Macmillan, Cancer Research UK, St Marks, the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The authors had approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Health Sciences of City, University of London to conduct the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Copyright 2014, used with the permission of the Health & Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved.

References

- 1.Cone MM, Herzig DO, Diggs BS et al. Dramatic decreases in mortality from laparoscopic colon resections based on data from the nationwide inpatient sample. Arch Surg 2011;146:594–9. 10.1001/archsurg.2011.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mamidanna R, Burns EM, Bottle A et al. Reduced risk of medical morbidity and mortality in patients selected for laparoscopic colorectal resection in England: a population-based study. Arch Surg 2012;147:219–27. 10.1001/archsurg.2011.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braga M, Vignali A, Zuliani W et al. Laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2005;242:890–6. 10.1097/01.sla.0000189573.23744.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, et al. Colour Study Group . Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:477–84. 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70221-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2010;97:1638–45. 10.1002/bjs.7160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S et al. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:2224–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09290-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munasinghe A, Singh B, Mahmoud N et al. Reduced perioperative death following laparoscopic colorectal resection: results of an international observational study. Surg Endosc 2015;29:3628–39. 10.1007/s00464-015-4119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biondi A, Grosso G, Mistretta A et al. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer: short- and long-term outcomes comparison. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2013;23:1–7. 10.1089/lap.2012.0276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor EF, Thomas JD, Whitehouse LE et al. Population-based study of laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery 2006–2008. Br J Surg 2013;100:553–60. 10.1002/bjs.9023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns EM, Mamidanna R, Currie A et al. The role of caseload in determining outcome following laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection: an observational study. Surg Endosc 2014;28:134–42. 10.1007/s00464-013-3139-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker JJ et al. Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD003125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tjandra JJ, Chan MKY. Systematic review on the short-term outcome of laparoscopic resection for colon and rectosigmoid cancer. Colorectal Dis Off J Assoc Coloproctology G B Irel 2006;8:375–88. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00974.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapco. LAPCO National Training Programme in Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Proportion Colorectal Resections Undertaken Laparoscopically Engl 2013. http://lapco.nhs.uk/activity-latest-HES-data.php (accessed 15 Oct 2014).

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Technology appraisal guidance TA105. Published: 23 August 2006: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta105

- 15.Murray A, Lourenco T, Verteuil R et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: systematic reviews and economic evaluation. Published Online First 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62293/ (accessed 15 Sep 2014).

- 16.Franks PJ, Bosanquet N, Thorpe H et al. Short-term costs of conventional vs laparoscopic assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial). Br J Cancer 2006;95:6–12. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohtani H, Tamamori Y, Arimoto Y et al. A meta-analysis of the short-and long-term results of randomized controlled trials that compared laparoscopy-assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. J Cancer 2012;3:49–57. 10.7150/jca.3621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biondi A, Grosso G, Mistretta A et al. Laparoscopic vs. open approach for colorectal cancer: evolution over time of minimal invasive surgery. BMC Surg 2013;13(Suppl 2):S12 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aylin P, Bottle A, Elliott P et al. Surgical mortality: Hospital episode statistics v central cardiac audit database. BMJ 2007;335:839 10.1136/bmj.39374.474965.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faiz O, Warusavitarne J, Bottle A et al. Laparoscopically assisted vs. open elective colonic and rectal resection: a comparison of outcomes in English National Health Service Trusts between 1996 and 2006. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1695–704. 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b55254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health. Reference costs 2012 to 2013 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/261154/nhs_reference_costs_2012-13_acc.pdf (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laudicella M, Walsh B, Burns E et al. Cost of care for cancer patients in England: evidence from population-based patient-level data. Br J Cancer 2016;114:1286–92. 10.1038/bjc.2016.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alva ML, Gray A, Mihaylova B et al. The impact of diabetes-related complications on healthcare costs: new results from the UKPDS (UKPDS 84). Diabet Med 2015;32:459–66. 10.1111/dme.12647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laudicella M, Olsen KR, Street A. Examining cost variation across hospital departments–a two-stage multi-level approach using patient-level data. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1872–81. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings P et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme. Br J Surg 2006;93:300–8. 10.1002/bjs.5216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat 1985;39:33 10.2307/2683903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reza MM, Blasco JA, Andradas E et al. Systematic review of laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2006;93:921–8. 10.1002/bjs.5430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns EM, Currie A, Bottle A et al. Minimal-access colorectal surgery is associated with fewer adhesion-related admissions than open surgery. Br J Surg 2013;100:152–9. 10.1002/bjs.8964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgway PF, Boyle E, Keane FB et al. Laparoscopic colectomy is cheaper than conventional open resection. Colorectal Dis 2007;9:819–24. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy KM, Kwong J, Pitzul KB et al. A cost comparison of laparoscopic and open colon surgery in a publicly funded academic institution. Surg Endosc 2014;28:1213–22. 10.1007/s00464-013-3311-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson BS, Coory MD, Gordon LG et al. Cost savings for elective laparoscopic resection compared with open resection for colorectal cancer in a region of high uptake. Surg Endosc 2014;28:1515–21. 10.1007/s00464-013-3345-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crawshaw BP, Chien H-L, Augestad KM et al. Effect of laparoscopic surgery on health care utilization and costs in patients who undergo colectomy. JAMA Surg 2015;150:410–15. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorn JC, Turner EL, Hounsome L et al. Validating the use of Hospital Episode Statistics data and comparison of costing methodologies for economic evaluation: an end-of-life case study from the Cluster randomised triAl of PSA testing for Prostate cancer (CAP). BMJ Open 2016;6:e011063 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012977supp_figures.pdf (262.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012977supp_tables.pdf (236KB, pdf)