Abstract

Background

The main barrier to optimal effect in many established population-based screening programmes against cervical cancer is low participation. In Norway, a routine health service integrated population-based screening programme has been running since 1995, using open invitations and reminders. The aim of this randomised health service study was to pilot scheduled appointments and assess their potential for increased participation.

Methods

Within the national screening programme, we randomised 1087 women overdue for screening to receive invitations with scheduled appointments (intervention) or the standard open reminders (control). Letters were sent 2–4 weeks before the scheduled appointments at three centres: a midwife clinic, a public healthcare centre and a general practitioner centre. The primary outcome was participation at 6 months of follow-up. Secondary outcomes were participation at 1 and 3 months. Risk ratios (RRs) overall, and stratified by screening centre, age group and previous participation, were calculated using log-binomial regression.

Results

At 6 months, 20% of the 510 women in the control group and 37% of the 526 women in the intervention group had participated in screening, excluding 51 women in total from analysis due to participation just before invitation and therefore not yet visible in the central records. The RR for participation at 6 months was 1.9 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.3). There was no significant heterogeneity between centres or age groups. Participation increased among women both with (RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.4 to 2.1) and without (RR 3.5; 95% CI 1.3 to 9.2) previous participation. The RRs for participation at 1 and 3 months were 4.0 (95% CI 2.6 to 6.2) and 2.7 (95% CI 2.1 to 3.5), respectively.

Conclusions

Scheduled appointments increased screening participation consistently across all target ages and screening centres among women overdue for screening. Participation increased also among women with no previous records of cervical screening.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This randomised pilot on the effect on participation of providing scheduled screening appointments was conducted within the routine screening programme and should therefore accurately represent the actual impact of implementation.

Follow-up of participation status in Norway is highly accurate due to mandatory central registration of all cervical tests.

Significant effects in all age groups and at three study sites strengthen the generalisability of the results.

The pilot was not powered to detect possible outcome differences caused by characteristics of screening delivery itself, such as amount of any own contribution or profession of the sample taker.

Although participation impact was demonstrated in this pilot, feasibility issues remain regarding large-scale implementation of the intervention.

Introduction

Low practical, financial and psychological barriers to participation in a population-based setting, together with effective communication, are required for equity of access to screening and the subsequent cancer prevention. Several cervical cancer audits analysing the screening history of women diagnosed with cervical cancer point to the lack of screening being the most important screening programme failure.1–4 It is important to acknowledge the voluntary nature of any screening programme, that there are benefits as well as harms and costs involved, and that women should be given the tools and opportunity to make informed decisions about their participation in population-based screening. However, since population-based screening against cervical cancer is an evidence-based and effective method to reduce morbidity and mortality of cervical cancer in the population with a low probability of harm, any logistic, financial and psychological barriers to participation should be minimised.

The trend in participation has been negative in several settings, including Norway with the 3.5-year test coverage at 67% in 2014, down from its peak of around 72% in 2004.5 The European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in cervical cancer screening, with supplements, give advice on how to improve participation through appropriate information to health professionals and targeted women, and by methods of screening delivery that lower thresholds for participation.6 7 Self-sampling in particular has been extensively tested to this effect in several European programmes.8 Other interventions or features that may be effective include phone calls, repeated reminders, free screening visits and scheduled appointments with easy rebooking.9–12 Significant pooled effects on participation (RR 1.5) of scheduled appointments in cervical cancer screening were reported in a systematic review covering three randomised studies.9 More recently, a Finnish report compared municipalities using scheduled and open second reminders and found a twofold difference in participation.13 Other screening programmes have also benefited from scheduled appointments; a non-randomised study from the UK breast cancer screening programme reported participation rates almost three times higher among women receiving timed second reminders.14

The purpose of the current study was to estimate the benefit, in terms of increased participation, of adding a prescheduled appointment to the current open reminder to participate in the Norwegian screening programme.

Methods

Setting

The screening programme in Norway targets women aged 25–69 with cytology screening at 3-year intervals. Laboratories are legally obliged to report all cervical screening and diagnostic activity to the Cancer Registry of Norway, where the screening management unit registers the notifications and monitors performance and outcomes. Residents are listed with their chosen general practitioner (GP), who generally takes the screening samples. Some women attend screening at a gynaecologist, and also midwives can take cervical samples, although the proportion is currently marginal. The screening management unit sends open invitations to screen 2 months before a new primary screening test is due. Participating women must make their own appointments for smear taking, achieving a total screening coverage of 67% over 3.5 years.5 If no screening test is registered within 12 months after the primary invitation, an open reminder is sent, bringing the 5-year coverage of screening to 74% of the target population. The coverage rates are below the 80% benchmark set by the national Quality Manual.15

Intervention

In the fall of 2014, 1087 women due to receive their reminder to screen after having failed to participate in the past ∼4 years, and 12 months after having received their primary invitation, were computer randomised 1:1 to receive either the standard open reminder or a reminder letter with a scheduled appointment. A further inclusion criterion was a current address with a postal code designating an area close to one of three participating screening centres. One screening centre was a private midwife and women's health centre employing three midwives experienced in smear taking in Oslo. The second centre was a GPs’ centre in Fredrikstad with a GP experienced in smear taking. The third centre was a public healthcare centre in Drammen with a midwife as smear taker having received additional training in cervical sampling by the collaborating midwives from Oslo. In Oslo and Fredrikstad, the women were charged the normal co-payment of 250–295 Norwegian Kroner (∼30 Euros) for smear taking; screening participation was free of charge in Drammen. All centres used either conventional or liquid-based cytology for screening. The reminder letters included information on the charge for screening and the profession of the smear taker.

Letters were mailed 2–4 weeks before the scheduled appointments. Women had limited possibilities to reschedule, as only specific days and time periods were dedicated to the pilot study in the screening centres. The appointments were scheduled primarily during normal office hours. Women were not required to confirm their attendance in advance.

Outcome

The primary outcome in the pilot was defined as participation at 6 months after mailing of reminders. This cut-off was chosen because 6-month participation is reported routinely in the Norwegian screening programme.5 We also hypothesised that women receiving open reminders might participate with a delay of some weeks compared with women receiving scheduled appointments and that this timing difference should not be reflected in the primary outcome. We also included participation at 1 and 3 months as secondary outcomes. Owing to a certain amount of systematic lag in notification from the screening laboratories and hence central registration, we waited 5 months after the completion of the 6-month follow-up for the last batch of allocated women before extracting the data for analysis. Thus, we can be reasonably certain to have captured all screening tests taken within the follow-up period required for the primary end point.

Power calculation

The 6-month participation rate after the reminder in Norway is around 20%.5 We assumed that the intervention would increase participation by 10%, in this case to 30%. Detecting such an effect with a 5% significance level and a power of 80% would require 600 invitations randomised 1:1. We included 1087 reminders as this proved logistically possible and in order to have a safety margin and the possibility of stratified analyses.

Statistical methods

The Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to plot the cumulative distribution of participation events after standard and intervention reminders. Log-binomial regression was used to estimate the relative probability (or risk ratio, RR) and absolute increase (or risk difference, RD) of participation at 1, 3 and 6 months following intervention. We also calculated effect estimates stratified by screening centre, previous participation and age at time of intervention. Randomisation and all statistical calculations were carried out in Stata V.14.0 MP by StataCorp, Texas, USA.

Ethical considerations

This project was covered by the legal mandate of the organised population-based cervical cancer screening programme in Norway pursuant to the Cancer Registry Regulations (Regulations of 21 December 2001 number 1477) as a pilot to implement improved screening invitation routines. In addition to the in-house ethicolegal assessment of the protocol in the Cancer Registry of Norway and consultation with the data protection representative at the University Hospital of Oslo, no additional external permissions were required.

Results

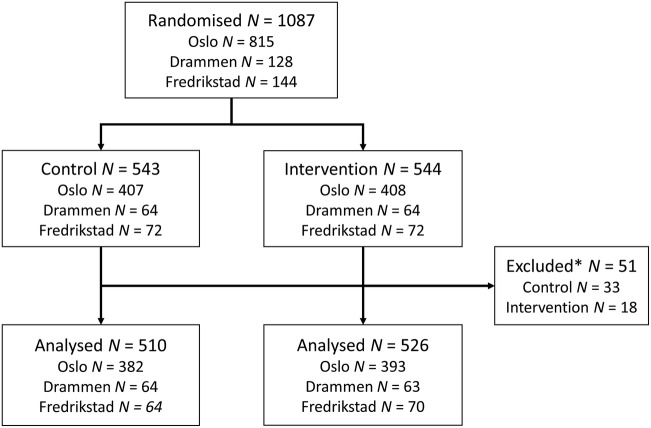

We randomised 1087 women due to receive their screening reminders for this health service study. Of these, 815 (74.9%) were from Oslo, 128 (11.8%) from Drammen and 144 (13.2%) from Fredrikstad (figure 1). According to 1:1 individual randomisation within each study site, 544 women were allocated to receive a scheduled appointment for screening in a personal invitation letter, and 543 women were allocated to receive the open reminder according to the standard invitation procedure. During follow-up, a screening test taken 1–3 months before allocation was registered for 51 of the randomised women. There is normally an up to 1 month lag in transfer and central registration of screening test results in the programme, but in some instances the lag can be more. These 51 women were excluded from the main analysis, as they were not eligible for further primary screening at the time of invitation. However, we estimated the main outcome separately also with these women included, as a sensitivity analysis.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart from randomisation to analysed population by study centre and intervention/control arm. *Owing to a lag in transfer for registration of screening tests in the Cancer Registry, 51 of the women randomised had participated in the past 3 months before allocation and mailing of letters. These women were not eligible for further primary screening and were excluded from the analysis.

The age distribution covered the target ages (25–69) of screening with the exception of women aged 25–26, as they cannot be eligible for a reminder letter according to standard invitation procedures. Age, number of previous tests and time since previous test were similar in the control and intervention arms (table 1). There were 218 (21%) women never previously screened in the study population.

Table 1.

Age and screening history by randomisation status

| Control (N=510) |

Intervention (N=526) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | Range | Mean | |

| Age (years) | 27–69 | 45.5 | 27–69 | 45.6 |

| Previous tests (n) | 0–19 | 4.0 | 0–17 | 4.2 |

| Time since previous test (y)* | 4.3–22.2 | 5.7 | 4.3–22.8 | 5.5 |

*In total 114 (22%) of the controls and 104 (20%) of the intervention group had no previous cervical tests.

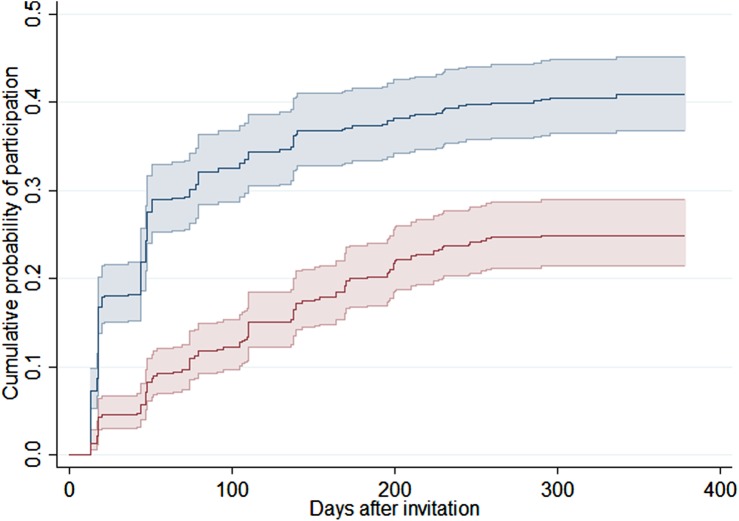

The slope of the Kaplan-Meier event curve (figure 2) indicates the frequency of participation events over time since mailing of the invitation or open reminder. The very marked difference in cumulative participation between arms in the beginning of follow-up diminished slightly as time progressed. However, plateaus reached at around 300 days are suggestive of a permanent difference in test coverage in the two arms. The 30-day periodicity visible in the participation events is due to a reporting artefact; some laboratories do not yet report the exact date of testing, only the month and year.

Figure 2.

The cumulative probability of participation in days after mailing of either an invitation with a scheduled screening appointment (blue) or standard open reminder letter (red) with pointwise 95% CIs indicated.

At 6 months of follow-up, 102 of the 510 (20.0%) controls and 196 of the 526 (37.3%) in the intervention arm had been screened. The difference in participation between arms was significant within each screening centre, age group and regardless of previous participation status (table 2). The RR for participation at 6 months overall was 1.86 (95% CI 1.52 to 2.29). The absolute increase in participation was 17.3% (95% CI 11.9% to 22.7%), corresponding to a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5.8. There was no significant heterogeneity in the effect estimates of the intervention between centres, age groups or previous participation status.

Table 2.

Screening participation at 6 months after intervention, stratified by screening centre, age group and previous participation status

| Screened/invited (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N=510) | Intervention (N=526) | RD (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| All | 102/510 (20.0) | 196/526 (37.3) | 0.173 (0.119 to 0.227) | 1.86 (1.52 to 2.29) |

| Centre | ||||

| Oslo | 75/382 (19.6) | 137/393 (34.9) | 0.152 (0.091 to 0.214) | 1.78 (1.39 to 2.27) |

| Drammen | 12/64 (18.8) | 28/63 (44.4) | 0.257 (0.101 to 0.413) | 2.37 (1.33 to 4.23) |

| Fredrikstad | 15/64 (23.4) | 31/70 (44.3) | 0.208 (0.053 to 0.364) | 1.89 (1.13 to 3.16) |

| Age group | ||||

| 27–39 | 42/197 (21.3) | 66/198 (33.3) | 0.120 (0.033 to 0.207) | 1.56 (1.12 to 2.18) |

| 40–54 | 33/181 (18.2) | 76/182 (41.8) | 0.235 (0.144 to 0.326) | 2.29 (1.61 to 3.26) |

| 55–69 | 27/132 (20.5) | 54/146 (37.0) | 0 165 (0.061 to 0.270) | 1.81 (1.22 to 2.69) |

| Previous participation | ||||

| Yes | 97/396 (24.5) | 180/422 (42.7) | 0.182 (0.118 to 0.245) | 1.74 (1.42 to 2.14) |

| No | 5/114 (4.4) | 16/104 (15.4) | 0.110 (0.031 to 0.189) | 3.51 (1.33 to 9.24) |

RD, risk difference; RR, risk ratio.

As secondary outcomes, we estimated the RR of participation after receiving a scheduled appointment at 3 and 1 month of follow-up. The estimates were 2.69 (95% CI 2.06 to 3.51) with 61 participation events among 510 controls and 169 among the 526 women in the intervention arm at 3 months, and 4.00 (95% CI 2.58 to 6.21) with 23 events among controls and 95 in the intervention arm at 1 month.

We also estimated the main outcome while including the 51 women with very recent participation before allocation who were excluded in the main analysis. In this sensitivity analysis, the screen at the time of allocation was ignored. There were 105 participation events among the 543 controls and 196 in the intervention arm with 544 women. The RR was 1.86 (95% CI 1.52 to 2.29), which is virtually identical to the main analysis.

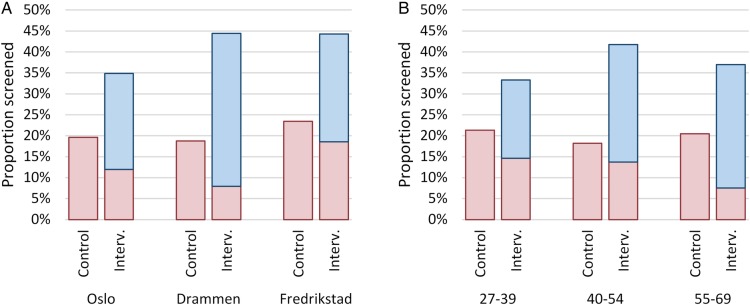

In the intervention arm, 66.8% of participating women attended screening as per the scheduled appointment; the remaining 33.2% opted to schedule their own appointment, as is standard in the programme. By logistic regression, there was a difference of borderline significance (p=0.050) in the proportion of participants choosing to participate as scheduled in Drammen versus Fredrikstad. There was also a higher proportion choosing to accept the scheduled appointment among the participating women aged 55–69 years compared with women aged 27–39 (p=0.008). The other pairwise differences shown in figure 3 were non-significant.

Figure 3.

Screening participation after the intervention (Interv.) of an added scheduled appointment to screen compared with controls (Control) receiving a standard open reminder. Results are stratified by screening centre (A) and age group (B). Participation is divided into screened as scheduled (blue) and screened by own separate appointment (red).

Discussion

This pilot to implement scheduled appointments to women overdue for their screening test in the Norwegian cervical cancer screening programme demonstrated improvements in participation in all targeted age groups.

Assuming that the absolute increase in the participating proportion observed in this study can be achieved in the entire 33% of women that currently fails to participate either spontaneously or after the first open invitation, the 5-year coverage of screening could increase by 6%, to 80% from the current 74%, by implementing the intervention nationally. This translates to more than 80 000 additional women covered by screening in each 5-year period, or 16 000 women per year. Although not significant, there was a trend for a larger relative impact on participation among women never previously screened. This group is of particular concern, because of a higher than average risk of cervical cancer.16

Strengths and limitations

Since the pilot was conducted as a randomised health service study integrated into the routine population-based screening programme,17 the results should reflect the expected performance of the piloted organisational improvement well. Also, since the central registration of cervical screening tests is universal in Norway, follow-up status with respect to participation is accurate and complete. We also demonstrated significant effects in the different age groups targeted by screening, and at three different study sites, strengthening the generalisability of the results. We did not collect information on losses to follow-up due to emigration or death. This would only be of concern for effect estimates if emigration or death were differential between the randomisation groups. Since the follow-up time was relatively short, the number of such events should be small, and cannot be expected to influence the results to a significant degree. The study was not powered to detect possible outcome differences caused by characteristics of screening delivery itself, such as cost of participating or profession of the sample taker. Although participation impact was demonstrated in this pilot, feasibility issues remain regarding large-scale implementation of the intervention.

Comparison with other studies

Participation in cancer screening is a complex issue and has many determinants. Level of education, marital status, self-assessed health, smoking, factors increasing healthcare contacts for gynaecological issues such as a history of sexually transmitted disease, pregnancies and hormonal replacement therapy are individual characteristics implicated in predicting participation in cervical cancer screening also in Norway.18 An organised, population-based approach to screening in general is likely to include elements that lower the threshold to participate and improve equity of cancer prevention.11 19 We have recently reported results of offering self-sampling to a group of women overdue for screening similar to the group offered scheduled appointments in this study. Self-sampling with an opt-out strategy compared with a standard reminder letter increased participation in all targeted age groups to a similar or slightly lower degree (RR 1.44; 95% CI 1.28 to 1.62) than the scheduled appointment intervention reported here.20 Self-collected samples currently do not allow cytology and are typically analysed for the presence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA requiring an additional clinician-collected sample for further triaging of HPV-positive women in most screening algorithms. In addition, the sensitivity of HPV testing from self-collected specimens is usually lower than from clinician-collected samples,21 although loss of accuracy can be mitigated by correct matching of the collection device and test method.22 For these reasons, self-sampling cannot currently be recommended as the primary method of screening, but may provide a valuable strategy if offered after adequate efforts to invite the woman to a clinician-collected sample have failed.

A small number of previous studies have been published on the effect of scheduled appointments compared with open invitations. An Australian cervical screening clinic conducted a randomised study in 1995 on the effect of three interventions: tagging of medical records, open invitations or scheduled appointments.23 Both open invitations and scheduled appointments increased participation compared with no intervention, with a higher point estimate reported for scheduled appointments (2.1 vs 1.7). A large Italian study, also published in 1995, studied the impact of scheduled appointments on participation in a cluster-randomised design and reported an effect corresponding to an RR of 1.6 compared with open invitation.24 A UK study from 1987 reported results of 240 women randomly assigned a standard open or scheduled invitation with a significant increase in the response rate of 15% from 32% to 47%, corresponding to an RR of 1.5.25 The effects of the intervention in our study are similar or somewhat larger than these previous findings. More recently, Finnish municipalities using scheduled appointments were reported to achieve a twofold participation after the second reminder compared with municipalities using open reminders.13 Different settings and time periods may influence the impact of the intervention. However, an important potential explanation for a putative larger effect compared with the previous randomised studies is the selection of the study group; our study included non-respondent women already invited by open letter once in the same screening round 12 months previously. Such selection may decrease the effect of the standard open reminder selectively compared with a scheduled invitation and provide higher relative effect estimates than would be observed in the unselected target population. The overall response rate is also lower after a reminder compared with the primary invitation to screen. Therefore, the effect size reported here may not be directly applicable to the first invitation in the screening round.

Policy implications

Even though participation, and presumably also test coverage in the target population, can be improved by the roll-out of scheduled screening appointments, such an approach would carry some costs. The inclusion of appointments in the reminder letters required close coordination between programme management and screening centres, which may be prohibitively expensive if conducted manually in contact with the thousands of GP and gynaecology practices currently taking smears in Norway. Centralising screening to a smaller number of screening centres, restricting the use of appointments to reminders (not primary invitations) in line with the currently reported pilot, and automating the scheduling system may mitigate costs and logistic complexity of the administration of scheduled appointments. Also, the possibility to easily reschedule the given appointment, especially if realised as a web-based universal solution with appointments outside normal office hours available, should have the potential to both reduce costs and increase the effect of the intervention further. Providing non-solicited appointments to women, a number of whom consequently will not attend, rebook or cancel, is a logistic problem manageable by calculated overbooking and regular monitoring of response rates. These results should also constitute relevant evidence for implementing scheduled appointments in other population-based screening programmes struggling with suboptimal participation, beyond Norway.

Conclusion

We have shown that scheduled appointments are effective at increasing participation in the Norwegian screening programme. This is true for all age groups targeted by screening and regardless of previous participation behaviour or type and organisation of the point of contact with sample taking health personnel.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank screening management team members Caroline Skudal, Gry Baadstrand Skare, Randi Waage and Ingrid Mørk Molund for IT support, data management, and input and help on the practical aspects of the pilot. They also thank the city of Drammen, midwife Anne Lise Tidemann Andersen and other personnel at the Marienlyst Healthcare Centre, the Oslo Jordmor og Kvinnesenter and the Kråkerøy Legesenter in Fredrikstad for their essential contributions.

Footnotes

Contributors: SL and TA conceived and designed the overall concept. AT, SL, CK, AS, KJ and CSF developed the practical aspects, final design and protocols. BE, TA, CK, AS, KJ, CSF and RL contributed to data acquisition. SL and BE analysed the data, and TA and AT reviewed the analyses. SL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published. SL is the guarantor.

Funding: This pilot was financially supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society (14/00100-1).

Disclaimer: The supporting institution did not have any role in the design, analysis or interpretation of results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Cancer Registry of Norway, Oslo University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Researchers interested in the anonymised individual data can contact the corresponding author for details.

References

- 1.Andrae B, Kemetli L, Sparén P et al. Screening-preventable cervical cancer risks: evidence from a nationwide audit in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:622–9. 10.1093/jnci/djn099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lönnberg S, Anttila A, Luostarinen T et al. Age-specific effectiveness of the Finnish cervical cancer screening programme. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:1354–61. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lönnberg S, Nieminen P, Luostarinen T et al. Mortality audit of the Finnish cervical cancer screening program. Int J Cancer 2013;132:2134–40. 10.1002/ijc.27844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasieni P, Castañon A, Cuzick J. Effectiveness of cervical screening with age: population based case-control study of prospectively recorded data. BMJ 2009;339:b2968 10.1136/bmj.b2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skare GB, Lönnberg S. Masseundersøkelsen mot livmorhalskreft. Årsrapport 2013–2014. [Cervical screening programme annual report 2013–2014] Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J et al. , eds European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in cervical cancer screening. Second edition. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anttila A, Arbyn M, De Vuyst H et al. , eds European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in cervical cancer screening. 2nd edn Second edition - Supplements. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdoodt F, Jentschke M, Hillemanns P et al. Reaching women who do not participate in the regular cervical cancer screening programme by offering self-sampling kits: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2375–85. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilloni L, Ferroni E, Cendales BJ et al. Methods to increase participation in organised screening programs: a systematic review. BMC public health 2013;13:464 10.1186/1471-2458-13-464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everett T, Bryant A, Griffin MF et al. Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(5):CD002834 10.1002/14651858.CD002834.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferroni E, Camilloni L, Jimenez B et al. How to increase uptake in oncologic screening: a systematic review of studies comparing population-based screening programs and spontaneous access. Prev Med 2012;55:587–96. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jepson R, Clegg A, Forbes C et al. The determinants of screening uptake and interventions for increasing uptake: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2000;4:i–vii, 1-133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virtanen A, Anttila A, Luostarinen T et al. Improving cervical cancer screening attendance in Finland. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E677–84. 10.1002/ijc.29176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson S, Brazil D, Teh W et al. Effectiveness of timed and non-timed second appointments in improving uptake in breast cancer screening. J Med Screen 2016;23:160–3. 10.1177/0969141315624937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer Registry of Norway. Kvalitetsmanual: masseundersøkelsen mot livmorhalskreft. [Quality Manual: cervical screening programme] Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Screening for squamous cervical cancer: duration of low risk after negative results of cervical cytology and its implication for screening policies. IARC Working Group on evaluation of cervical cancer screening programmes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:659–64. 10.1136/bmj.293.6548.659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hakama M, Malila N, Dillner J. Randomised health services studies. Int J Cancer 2012;131:2898–902. 10.1002/ijc.27561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen BT, Hukkelberg SS, Haldorsen T et al. Factors associated with non-attendance, opportunistic attendance and reminded attendance to cervical screening in an organized screening program: a cross-sectional study of 12,058 Norwegian women. BMC Public Health 2011;11:264 10.1186/1471-2458-11-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weller DP, Patnick J, McIntosh HM et al. Uptake in cancer screening programmes. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:693–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70145-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enerly E, Bonde J, Schee K et al. Self-Sampling for human papillomavirus testing among non-attenders increases attendance to the Norwegian Cervical Cancer Screening Programme. PLoS ONE 2016;11:e0151978 10.1371/journal.pone.0151978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:172–83. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Arbyn M et al. High-risk HPV testing on self-sampled versus clinician-collected specimens: a review on the clinical accuracy and impact on population attendance in cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer 2013;132:2223–36. 10.1002/ijc.27790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pritchard DA, Straton JA, Hyndman J. Cervical screening in general practice. Aust J Public Health 1995;19:167–72. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1995.tb00368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segnan N, Senore C, Giordano L et al. Promoting participation in a population screening program for breast and cervical cancer: a randomized trial of different invitation strategies. Tumori 1998;84:348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson A, Leeming A. Cervical cytology screening: a comparison of two call systems. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:181–2. 10.1136/bmj.295.6591.181-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]