Abstract

To photo-catalytically degrade RhB dye using solar irradiation, CeO2 doped TiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs. All emission spectra showed a prominent band centered at 442 nm that was attributed to oxygen related defects in the CeO2-TiO2 nanocrystals. Two sharp absorption bands at 1418 cm−1 and 3323 cm−1 were attributed to the deformation and stretching vibration, and bending vibration of the OH group of water physisorbed to TiO2, respectively. The photocatalytic activities of Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals were investigated through the degradation of RhB under UV and UV+ visible light over a period of 8 hrs. After 8 hrs, the most intense absorption peak at 579 nm disappeared under the highest photocatalytic activity and 99.89% of RhB degraded under solar irradiation. Visible light-activated TiO2 could be prepared from metal-ion incorporation, reduction of TiO2, non-metal doping or sensitizing of TiO2 using dyes. Studying the antibacterial activity of Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals against E. coli revealed significant activity when 10 μg was used, suggesting that it can be used as an antibacterial agent. Its effectiveness is likely related to its strong oxidation activity and superhydrophilicity. This study also discusses the mechanism of heterogeneous photocatalysis in the presence of TiO2.

Solar energy is uniquely poised to solve major energy and environmental challenges that are being faced by humankind. As such, it is important to develop a suitable environmentally-friendly technology that permits the full range of the solar spectrum to be used for simultaneously solving energy and environmental challenges. It has been proposed that it is possible to address these challenges using nanocomposite materials that are capable of solar photocatalytic conversion1,2. Nanocomposite materials have a mixture of different chemical compositions and have received wide interest from fundamental and applied science researchers. The physical properties of these materials can be combined to produce materials that have desirable characteristics. Optical or biological characteristics can change with decreasing particle sizes, which is a major reason for interest in nanocomposite materials3. For example, metal oxide nanocomposites have excellent physical properties, such as high hardness and melting points, low densities and coefficients of thermal expansion, high thermal conductivities, good chemical stabilities. They also have improved mechanical properties, such as higher specific strengths, better wear resistance and specific modulus, and have wide potential for various industrial fields4,5.

Metal oxide semiconductor photocatalysts (MOSPs) offer a number of opportunities for enhancing energy efficiency and reducing environmental pollution through minimizing carbon footprints6,7. Titanium oxide (TiO2) is a MOSP of particular interest because of its unique properties, such as being a wide forbidden energy band gap semiconductor, its non-toxicity to living organisms, stability in water, and strong photocatalytic properties when its crystal grain size is reduced to tens of nanometers8. The strong redox power of photo-excited TiO2 was realized with the discovery of Honda-Fujishima effect in 1972, where Fujishima et al., reported the photo-induced decomposition of water on TiO2 electrodes9. TiO2 acts as a photocatalyst under ultraviolet light, but this only contributes to approximately 2–5% of total solar power, so the photovoltaic or photocatalytic activity of TiO2 is limited10,11. Another major limitation of TiO2 is massive photogenerated electron−hole recombination, which limits the efficiency of the photocatalyst. CeO2, on the other hand, has been shown to be a promising candidate because of its desirable band edge positions and it has been successfully used in a number of photocatalytic processes, such as detoxification and hydrogen production. The redox shift between Ce4+ and Ce3+ can create a high capacity for the system to store or release oxygen under oxidizing or reducing conditions12,13,14,15. Many studies have reported that CeO2-TiO2 systems have enhanced properties under UV solar irradiation. In particular, Zhang et al., found that cerium doping could prohibit the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs16. Yan et al. reported the preparation of Ce-doped titania through a sol-gel auto-ignition process that had strong absorption in the UV-vis range and a red-shift in its band gap transition17,18. It has been proposed that doping the base photocatalyst with impurities is best way to enhance the utilization of solar energy and to inhibit the recombination of photogenerated e− - h+ pairs. Xiao et al., synthesized Ce-doped TiO2 mesoporous nanofibers using collagen fibers as a biotemplate and showed that RhB dye on the Ce0.03/TiO2 nanofibers degraded by 99.59% over 80 min under visible light, much higher than undoped TiO2 nanofibers or the commercial product Degussa P2519,20. In this study we report a detailed investigation of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals and their structural properties, crystallinities, phase transformations, morphologies, and photocatalytic and band gap engineering. Photocatalytic activities were examined using Rhodamine B (RhB; 99.95% purity) as a model impurity under solar irradiation (λ > 365 nm). For the first time we also present the antibacterial activity of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals that were prepared using a hydrothermal method and the mechanism responsible for the synergistic effects of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals is also discussed in detail.

Experimental section

Chemicals & typical synthetic process for CeO2 - TiO2 nanocomposites

All chemical reagents (analytical grade) were used as received (E-Merck 99.99%) without further purification. To synthesize mixed cerium-titanium oxide nanocomposites, 0.1 Mol % of cerium (III) nitrate hexahydrate [Ce(NO3)3·6H2O] and 0.1 Mol % titanium (IV) nitrate [Ti(NO3)4·4H2O] were combined with distilled water and stirred thoroughly using a magnetic stirrer. For hydrothermal synthesis, nearly 0.5 Mol % cetyltriethylammonium bromide (CTAB) [C19H42BrN] solution was prepared and added dropwise to the cerium-titanium solution that was vigorously stirred, the color of the solution turned yellowish dark pink in 5 min, indicating the beginning of the reaction. Then the color of the solution became deeper and deeper with the increase in reaction time till it became completely dark, demonstrating the formation of CeO2-TiO2 nanoparticles. The homogeneous mixture was loaded into a 250 mL Teflon-coated stainless lined autoclave, which was then filled with distilled water to 70% of the total volume. Then the above solution was transferred to Teflon lined autoclave at 240 °C in a micro oven for 24 hrs. The synthesized nanoparticle was annealed at 700 °C in a microprocessor controlled single zone furnace for 9 hrs. After the reaction was completed, the controlled furnace was cooled to room temperature and the resultant solid products were collected, washed several times with absolute ethanol and distilled water and then dried at 140 °C for 9 hrs. Finally, the obtained nanoparticles of CeO2-TiO2 were used for different characterization studies.

Sample characterization

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) measurements were made on a HITACHI H-8100 electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The samples for HRTEM characterization were prepared by placing a drop of colloidal solution on carbon-coated copper grids and drying at room temperature. The elemental compositions were determined using selected area electron diffraction (SAED) (IH-300X). Optical absorption was measured using a Varien Cary 5E spectrophotometer with excitation wavelengths ranging from 350–700 nm. The confirmation of CeO2-TiO2 nanoparticles was performed using a UV-vis spectrophotometer. Aliquots (5 mL) of the suspension were measured to determine the surface plasmon resonance absorption maxima using distilled water as reference. The functional groups in the CeO2-TiO2 nanocrystals were evaluated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and the spectra were recorded with a Brukker IFS (66 V) spectrometer. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were made using an ESCALAB 250 photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo-VG Scientific, USA) with Al Kα (1486.6 eV) as the X-ray source. Photoluminescence (PL) measurements of the as-synthesized products were carried out using an F-4500 KIMON fluorescence spectrophotometer at room temperature with a Xe lamp as the excitation source. The excitation wavelength used was 397 nm.

Dye adsorption testing

The dye activity performances of the synthesized nanocomposites were tested for their ability to remove textile dye in an aqueous solution. RhB, a carcinogenic textile dye, was used as the organic impurity model. The RhB adsorption experiment was conducted in 15 mL capped glass tubes containing 5 mL of RhB solution (15 mg/g) and 15 mg of the synthesized composite nanocrystals. The sample-containing glass tubes were then placed into a Certomat WR-Braun Biotech International temperature-controlled water bath shaker at a constant agitation speed (120 rpm) and 25 ± 1 °C. After some time the glass tubes were removed. The RhB filtrate was separated from the solid material. Absorbance of the filtrate was then measured using a U-3501 Shimadzu UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer at the wavelength maximum of RhB (λmax = 500 nm). The concentration of RhB that remained in the sample solution was calculated from a calibration curve. The percentage of RhB adsorption expressed as shown in Equation: % Adsorption = ((C0 − Ct)/C0) × 100%, where C0 is the initial concentration of RhB dye (mg/L) and Ct is the concentration of RhB dye remaining at time (t) (mg/L).

Photocatalytic performance test

The photocatalytic activity of each sample was studied from the degradation of RhB under UV (λ < 400 nm), visible (λ > 400 nm), and UV + visible light. The UV and visible irradiances at the reactor surface were 0.15 W/m2 (Philips 15 W/G15 T8, Holland) and 14.5 W/m2 (Philips 18 W/54 1M7 India), respectively. The catalytic material loadings for the experiments were 0.5 g/L and the average reactor temperature was maintained at 35 °C. The solutions were kept in the dark for two hrs to achieve adsorption−desorption equilibrium. The experiments were carried out by simultaneous exposure of the catalysts, each of which had 30 mL of RhB (1 mM) that was being stirred. The catalyst-loaded RhB solutions were illuminated under UV, visible, and UV + visible light for 60 min and sampling was performed at 15-min intervals. At specific time intervals the photo-reacted solutions of the centrifuged samples were analyzed by recording variations in the absorption band maximum (664 nm) using a UV−visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 1700, Japan).

Antibacterial activity performance

The antibacterial activities were evaluated against E. coli, a Gram-positive bacterium. E. coli was obtained in frozen form from the American Type Culture Collection. The bacteria were thawed on ice for 20 minutes before being placed on an agar plate. The plate was then dried before incubation for 16 hrs in a standard cell culture environment (37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% air). A single colony of E. coli was selected using a 10-μL loop and inoculated into a centrifuge tube containing 5 mL of cryptic soy broth. Bacteria in the centrifuge tube were then incubated at 37 °C under agitation at 200 rpm for another 16 hrs. At that point, the bacteria solution was diluted in cryptic soy broth to an optical density of 0.52 at 600 nm using a microplate reader. According to the standard curve correlating bacteria number with optical density, this value was equivalent to 5 × 106 cells/mL. The cells were further diluted in cryptic soy broth to 5 × 104 cells/mL before being added to a new centrifuge tube at 5 mL/tubes. Concentrated Ce-TiO2 nanoparticles in solution were added to bacteria tubes at different doses (0.08 mM (low dose), 0.15 mM (medium dose), and 0.3 mM (high dose)). A tube of bacteria without nanoparticles served as a control. Bacteria were then incubated under agitation for four hours, 12 hrs, and 24 hrs, before a 200-μL bacteria solution was transferred to a 100-well plate for optical density readings at 600 nm using a microplate reader.

Results and Discussion

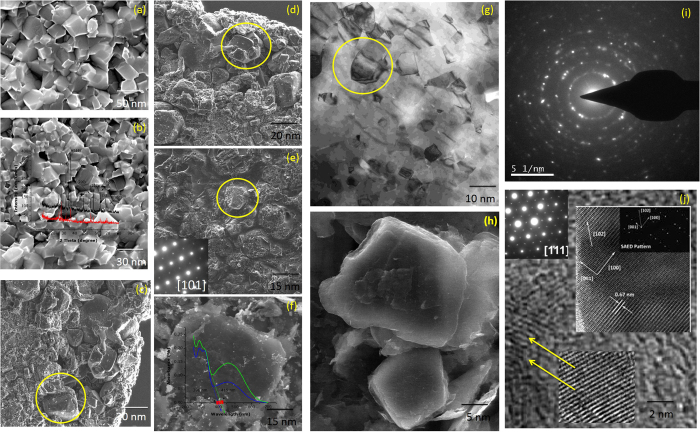

High-resolution TEM images of the ceria-doped TiO2 nanocomposites are shown in Fig. 1(a–j). It is apparent that the nanocomposites consist of a large quantity of spherical-like cubic nanocrystals with a narrow size distribution. Upon addition of 0.5 Mol% CTAB and calcination for 3 hrs, aggregation of CeO2 nanocrystals occurred. These nanocrystals could not be clearly distinguished from each other21,22,23. When the calcination treatment was prolonged to 5 hrs, the morphology became more regular and the nanocrystals displayed a suitable morphology, with the product being dispersive, as shown in Fig. 1(a–e), when the calcination time was extended to 7 hrs, it can be seen from Fig. 1(f–h) that the nanocrystals were overburnt and had irregular forms. Aggregation of spherical particles occurred along with the formation of crystals; however, the nanocrystals were difficult to separate. This may have occurred because the long calcination time caused collapse of the morphologies. In the bright field image, all of the synthesized samples appeared to consist of many semi-aggregated round particles. The average particle size of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocomposites, as shown in Fig. 1(b–d), was estimated to range from 15–30 nm and Ce-Ti particle sizes (Fig. 1(g–h)) ranged from 5–10 nm. The HRTEM image also shows individual CeO2 nanocrystals with good crystallinity and clear lattice fringes, highlighting that both materials had regular spherical shapes and narrow size distributions. The composites prepared hydrothermally consisted of 5–10 nm particles that were agglomerated to form porous, irregular networks and consisted of monodisperse CeO2 nanoparticles, as shown in the HRTEM images.

Figure 1. (a–j) High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy images of CeO2 doped TiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

The HRTEM micrographs and selected area diffraction patterns of the Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals are shown in Fig. 1(i,j). The diffraction peaks were very diffuse, suggesting that the texture was polycrystalline with small grain sizes24,25,26. Therefore, the distributed pore sizes and mean pore diameters obtained from N2 adsorption–desorption analyses would represent the values for the whole crystal network. It should be noted that the particle sizes of CeO2 obtained in presence of nanotitania were small, even in the absence of additional stabilizing agents, and this included the CeO2 nanoparticles deposited on the TiO2 lattice. Since Ti is a known catalyst for redox reactions, this suggests that Ti catalyzed the formation of CeO2. Because the surfaces of TiO2 nanoparticles were not completely covered with CeO2, it is possible that Ti and Ce sites featuring different ligands like (–Ce) or (–COOH) could be used for optoelectronic devices. The total Ti content of the sample was 4.8 wt%, corresponding to a Ce content of 5.2 wt%. The monocrystalline ceria also showed a layer-by-layer structure (Fig. 1(j)), which was consistent with results from the XRD pattern provided in the Supplementary Information Figure S1. The selected area diffraction pattern of the nanocrystals in the bottom of Fig. 1(j) confirmed that Ce was monocrystalline along the [111] direction (inset Fig. 1(j)). The selected area diffraction pattern with diffraction rings was calculated and confirmed the presence of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocrystals in Fig. 1(i).

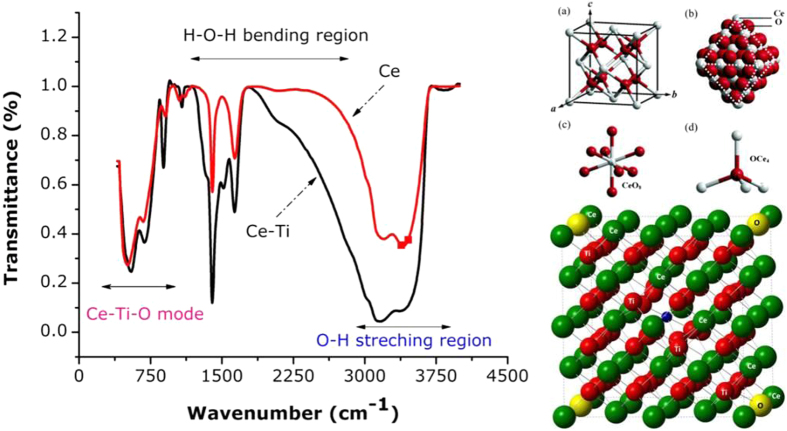

The elucidation of structural features using FTIR is shown in Fig. 2. In the FTIR spectra of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocrystals and TiO2 treated with a coupling agent had absorption peaks at 3426 cm−1 and 1626 cm−1 and the spectra were analyzed between 400 cm−1 and 4500 cm−1. The nanocrystals exhibited bands assigned to (Ce-Ti-O) and Ti-O near 544 cm−1 and 798 cm−1 that were from the longitudinal optical mode (LOM). The red shift of the LO mode of amorphous TiO2 from 870 cm−1 to 798 cm−1 was a consequence of the presence of CeO2 nanograins27,28,29,30. The intensity of the band assigned to the LO mode of the amorphous TiO2 phase increased with increasing TiO2 content. The surface hydroxyl (OH) groups of Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals have been recognized to play an important role in photocatalytic behavior. This is because they adsorb reactant molecules and directly participate in the reaction mechanism through trapping photogenerated holes to form hydroxyl radicals. There are limited reports identifying OH groups on the surface of Ce-O-Ti31,32. We suggest that the two sharp absorption bands at 1418 cm−1 and 3323 cm−1 were from deformation and stretching, and the bending vibration of the OH group of water physisorbed to TiO2, respectively, while the shoulder at 3238 cm−1 from Ti-OH bonds can be ascribed to the strong interaction between Ti ions and OH groups. The chemical bonding of the nanopowder was scrutinized by correlating the peaks in the spectrum to the vibration or stretching of various functional groups. The broad band peaks located at 3400 cm−1 & 1600 cm−1, which were observable in as-prepared nanopowders, were attributed to the stretching and bending vibrations, respectively, of O-H groups from absorbed water molecules33. These two broad bands were not detected in the spectra of calcined powders because of dehydration during calcination. The absorption band at 1380 cm−1 that can be attributed to the existence of nitrate groups was only observed in the as-synthesized sample, suggesting that the complete removal of this functional group can be achieved after calcination.

Figure 2. Fourier Transmittance Infrared spectrum CeO2 doped TiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

For the nanosamples calcined at 700 °C over 9 hrs, the appearance of new bands below 1000 cm−1 were observed. These peaks are from the stretching modes of Ce-O and Ti-O nanocrystals according to Zhou et al.34 & Phoka et al.35. In this study, there was little absorption at the same wavelengths in the spectra, indicating that -OH groups disappeared when nano-TiO2 was treated using a coupling agent. The reasons for this were chemical reactions between -OH groups of TiO2 and the Ce-Ti-OH group of the coupling agent in Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals. The absorption peaks at 512 cm−1 in both spectra were the character absorption peaks for Ce-O-Ti vibrations, which showed that the coupling agent only reacted with -OH groups and not TiO2. This shows that the structure and composition of TiO2 did not change after treatment with the coupling agent. Normally the defect structure of Ce-Ti-O formed by oxygen vacancies favors the adsorption of water on the surface and then dissociation of water into hydroxyl groups and protons. This dissociation behavior leads to charged surfaces on the Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals because of the loss or gain of protons and complexation reactions of surface hydroxyl groups.

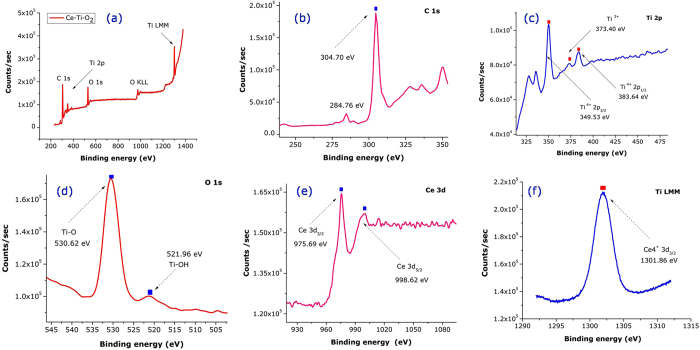

XPS measurements were carried out to understand changes in surface chemical bonding and the electronic valence band positions of Ti and Ce in the TiO2 and 0.5% CeTi nanostructures. Figure 3(a) presents the overall XPS spectrum containing peaks for Ce, Ti, O, and C. The XPS spectrum of 0.5% CeTi shows a binding energy peak for Ce 3d along with the Ti 2p and O 1 s orbitals. The peak at 284.76 & 304.70 eV signals the presence of elemental carbon as a reference. In Fig. 3(e) it is clear that the dominant spin–orbit doublet of 3d CeO2 was from Ce3+ and the smaller doublet was from Ce4+ at higher binding energies36. From the deconvolution result, we also observed additional satellite peaks for Ce3+, but not for Ce4+. It has previously been reported that rare earth compounds with unpaired electrons can produce an extra satellite peak from photoelectron energy gain and loss37. Ce3+ has one 4f electron, but Ce4+ has none. Accordingly, the extra electron can produce additional electronic transitions and give rise to the satellite peaks38. The XPS spectra of the Ti 2p region of TiO2 and 0.5% CeTi are shown in Fig. 3(c). The Ti 2p peak in TiO2 appears as a single, well-defined, spin-split (3.2 eV) doublet that was assigned to Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2, which corresponded to Ti4+ in the tetragonal structure.

Figure 3. (a–f) X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy images of CeO2 doped TiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

The binding energies of the peaks were found to be 383.64 eV for Ti 2p1/2 and 349.53 eV for Ti 2p3/2, which were in agreement with the binding energies of TiO2 previously reported39. This shifting corresponded to an intermediate oxidation state of Ti from tetra- to trivalent. The Ti 2p1/2 region was fitted into two peaks of Ti3+ and Ti4+ (373.40 and 349.53 eV). Figure 3(c) shows the binding states of oxygen in TiO2, with the O 1 s XPS peak fitted to three deconvoluted peaks. These peaks appeared at 349.53, 373.40, and 383.64 eV. The peak at 349.53 eV is typically from the O2− ion in the TiO2 crystal structure. The binding energy peaks at 349.53, 373.40 and 383.64 eV were assigned to Ti-OH, Ti-O and Ti-O-Ce, respectively. The binding energy of O 1 s for surface oxygen shifted from 530.62 to 521.96 eV. This O 1 s peak shift suggests that Ti and Ce chemically interact with each other in the CeO2-doped TiO2 system. Figure 3(d) shows the Ce 3d peaks, which confirmed the doping of Ti into CeO2 nanomaterials. The peak intensity was not strong because of the low dopant concentration. The core level Ce 3d3/2 and Ce 3d5/2 peaks were observed at binding energies of 530.62 and 521.96 eV, respectively. The main XPS peak for O1s appeared at 530.62 eV. A small hump was also noticeable at 521.96 eV that was assigned to the adsorbed oxygen in CeO2. The peak position of oxygen was slightly shifted because of the incorporation of Ti ions into CeO2 when the peaks were compared with pure CeO2 nanocrystals. From the deconvolution results we found another small, intense peak for O 1 s at 505.32 eV that was not from the presence of Ce3+ or Ce4+, but was probably from the presence of OH on the sample surface. The XPS analyses confirmed the doping of Ce and successive formation of Ce-doped TiO2 nanosamples. Figure 3(e) shows the Ce core level spectrum of CeO2 from 930–1080 eV. From the XPS spectrum it is evident that the 3+ and 4+ valence states were present because of the non-stoichiometric nature of the material40,41. The main intense peaks of Ce3+ 3d3/2 and Ce3+ 3d5/2 were located at binding energies of 975.69 and 998.62 eV, respectively. The other peaks for Ce4+ 3d3/2 and Ce4+ 3d5/2 appeared at 1301.86 eV.

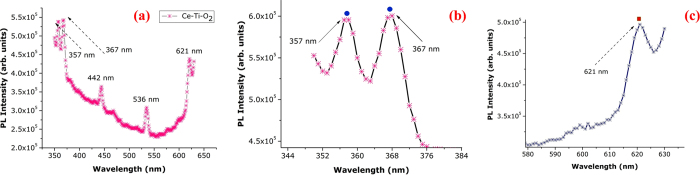

The room temperature PL spectra of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocrystals using a 30 W laser control are shown in Fig. 4(a–c). At higher temperatures the PL spectra peaked at 600 nm (1.88 eV) in the red region and no additional changes in the spectral shapes or peak positions occurred to room temperature (RT)42,43,44. Two optical edge centers (green and red emission bands) of CeO2 and TiO2 nanocrystals were investigated using PL at RT. The emission spectra of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals with different Ce:Ti mole ratios are presented in Fig. 4(a–c). The emission spectra of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocomposition were characterized by three peaks near 357, 367 and 442 nm. All emission spectra (λexc = 320 nm) showed a prominent band centered at 442 nm that was attributed to oxygen-related defects in the CeO2-TiO2 nanoregime. The dominant defects in CeO2 are oxygen vacancies45,46,47,48. The intensity of the band at 442 nm increased with increasing CeO2 content in the CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocomposites. The formation of these compounds is likely the reason for optimal PL characteristics. Transmission from the nanocomposites was observed to be the lowest, while higher transmission occurred from the nanocrystals. However, it has been observed that the transparency of the nanocrystals adversely affected their PL response, suggesting the least transparent nanocrystals exhibit the highest PL intensities. The two prominent peaks at 357 nm and 367 nm are characteristic of the Ce3+ state. The XPS studies discussed earlier confirmed the presence of Ce4+ and Ce3+ states.

Figure 4. (a–c) Photoluminescence images of Ce-Ti-O2 nanocrystals by hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

In this work we have reported the first dark blue nanocomposites that become increasingly transparent as the annealing temperature increased. Based on the observed shape evolutions, a possible formation mechanism for CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals produced hydrothermally is presented for the first time. However, trivalent Ce has only one electron in the 4f state. The ground state of Ce3+ is split into 2F7/2 and 2F5/2. The next highest state originates from the 5d state and 4f–5d transitions are parity allowed. Unlike the 4f electron with the shielding effect of the outer shell 6 s and 5p electrons, the shift of the 5d, and hence the d–f emission band of the Ce3+ ion, is heavily dependent on the local crystal field surrounding the Ce3+ ion. Thus, the emission wavelength of Ce3+ is very sensitive to the crystallographic environment. Decreased PL intensity of the CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocomposites was observed when the cerium concentration increased because of increasing intra-ionic and non-radiative relaxation among Ce ions. When splitting of the 5d state is large and the energy difference between the lowest 5d sublevel and the ground state 4f configuration of Ce3+ is small, a red shift of emissions takes place. To the best of our knowledge, we have shown the first emission shift when TiO2 concentrations increase. When the TiO2 concentration is high, the unit cell of CeO2 becomes larger. This leads to the lowest sublevel of the 5d state of Ce3+ decreasing in energy because of a stronger crystal field when the TiO2 concentration is high. We observed a red shift of emissions from 536 nm to 621 nm.

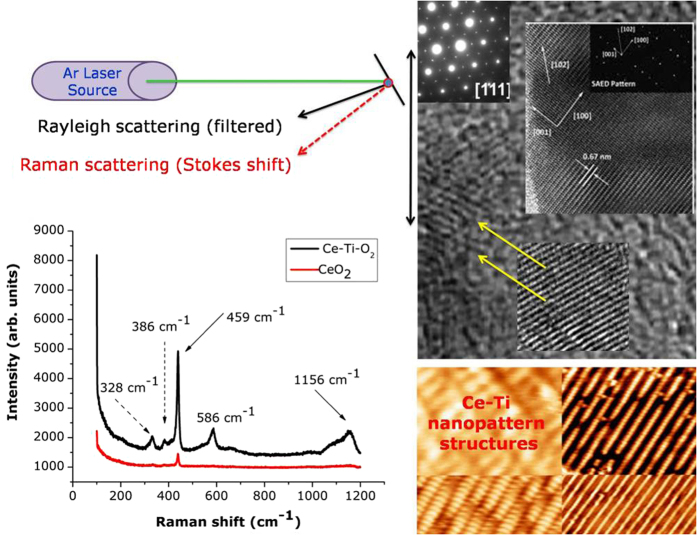

Raman spectroscopy of polycrystalline materials has a higher sensitivity for characterizing the crystal phase of oxide nanocomposites than HRTEM. The Raman scattering profiles provided further evidence that the rutile phase was the major crystalline structure in all three targets. Figure 5 shows the Raman spectra for the TiO2 nanocrystals and the sharp peak at 328 cm−1 confirmed the existence of anatase TiO2. However, this peak value deviated from the theoretical value of 244 cm−1 and this blue shift may be caused by non-stoichiometry or the small size effect49,50,51. Raman scattering also showed two strong peaks at 459 cm−1 and 586 cm−1 representing the rutile Eg and rutile A1g phases, respectively52,53. Since only the O atoms move, the vibrational mode was almost independent of the ionic mass of cerium. The broad peak in the Raman spectrum was mainly from stretching vibrations of CeO2 nanoparticles, which is the building block for the formation of nanocrystals. A weak peak at 1156 cm−1 was observed in the TiO2 spectrum that showed the anatase phase was present. More explanation about the rutile and anatase phases from the XRD pattern is discussed in the supplementary information (SI) and the existence of a small amount of anatase phase TiO2 is apparent in the nanocomposites. The Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals had a very strong signal for the anatase phase; the doping of Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals may enhance the growth of anatase TiO2.

Figure 5. Raman spectrum of Ce-Ti-O2 nanocrystals.

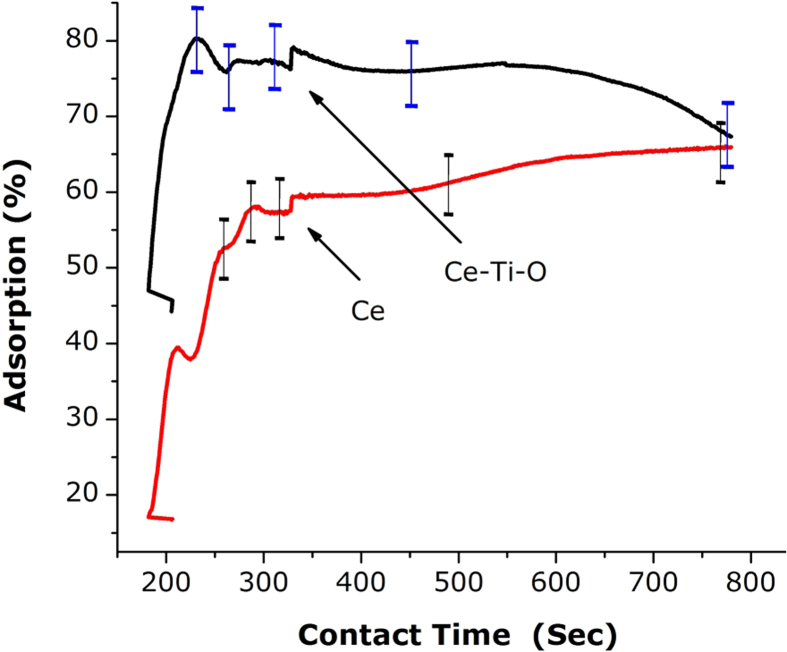

The performance of the as-synthesized nanosamples was tested. Pure Ce and doped Ce-TiO2 nanosamples showed strong absorptive capacity for RhB dye, and because of this RhB was used as a model pollutant54,55,56,57,58,59,60. Figure 6 shows the time-dependent RhB adsorption by Ce and Ce-TiO2 at room temperature. The removal efficiencies of both nanosamples showed similar trends, where adsorption rates increased rapidly over the first 3 min and then stayed steady as time passed. The equilibrium times for pure Ce and Ce-TiO2 were found to be 3 min and 5 min, respectively. The ability of Ce-Ti-O to adsorb the RhB dye was higher than that for pure Ce, which is apparent from the curve. The smaller particle size of CeTi than that of pure Ti may play an important role in the adsorption process61,62,63,64. This is likely because smaller particles have higher surface areas. In the adsorption study, large surface areas means the small particles are favored because more active sites are available for molecules that can attach to the surface of adsorbent65,66,67.

Figure 6. Effect of contact time on RhB adsorption Ce-Ti-O.

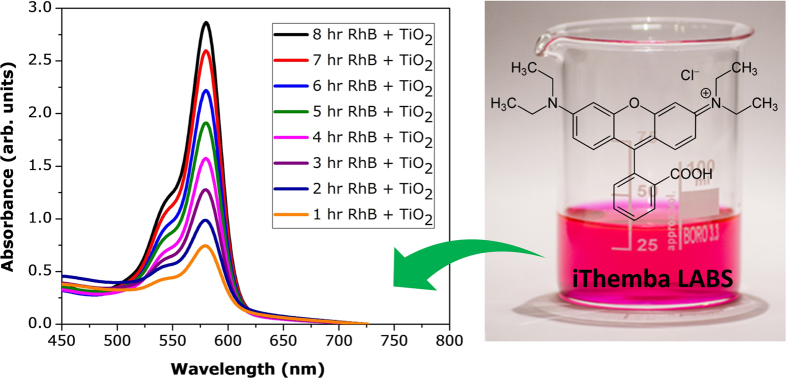

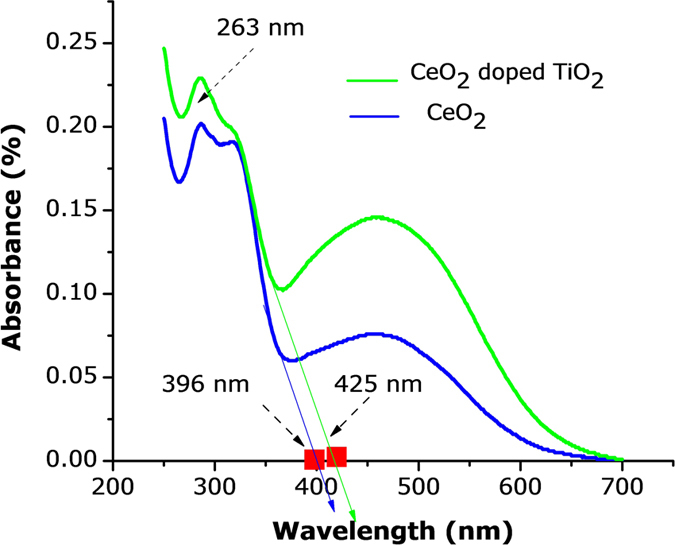

The CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals showed the potential for photocatalytic activity. The absorption spectra of RhB pink solution after 1 hr of UV-vis light irradiation in the presence of different CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals is shown in Fig. 7. The percentage decomposition of the RhB pink absorption peak (578.21 nm) after 1 and 2 hrs was 93%. These results highlight the superior photocatalytic response of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocomposites68,69,70,71,72. The decrease in intensity of the absorption peaks, both in the visible and ultraviolet regions, with irradiation time indicated that the RhB was degraded. To compare the photocatalytic activity of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals, the absorption spectrum of the RhB solution after 2 hrs irradiation in the presence of TiO2 nanocrystals was also recorded. The percentage decomposition of RhB absorption peak after 8 hrs irradiation in the presence of CeO2-doped TiO2 photocatalysts increased to 99.89%. These results highlight that the addition of Ce improves the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanocrystals. The visible light photo activity of ceria-doped TiO2 can be explained by a new energy level produced in the band gap of TiO2 through the dispersion of ceria nanoparticles in the TiO2 matrix73,74. As shown in Fig. 7, an electron can be excited from the defect state to the TiO2 conduction band by a photon with energy equal to hv2. An additional benefit of transition metal doping is the improved trapping of electrons to inhibit electron-hole recombination during irradiation. The UV–visible absorption spectrum of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystals is shown in Fig. 8. Although the wavelength of the Varian Cary 5E spectrometer was limited by the light source, the absorption band of the cerium oxide nanoparticles increased in wavelength because of quantum confinement of the excitons present in the samples compared with bulk cerium oxide particles.

Figure 7. Photocatalytic studies of CeO2 doped TiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

Figure 8. UV-is image of Ce-Ti-O2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

The UV-vis spectrum showed strong absorptions below 263 and 396 nm, and a well-defined absorbance peak at around 425 nm. It revealed that the band gap of CeO2 nanocrystals was approximately 4.79 eV, which is greater than the value for the bulk CeO2 (Eg = 3.18 eV). As a result, quantum size effects will increase the bandgap leading to a blue shift in the absorption spectrum. Observing this optical phenomenon indicated that our nanoparticles showed the quantum size effect. The estimated bandgap energy (Eg) of the samples was generated by substituting the obtained absorption edge (λ) values into the formula: Eg (eV) = 1260/λ (nm). As can be seen from Fig. 8, the absorption edges of Ce-Ti (425 nm) shifted to higher wavelength (red shift) compared to the absorption edges of Ti (396 nm), indicating a change of band gap (Eg) from the presence of Ce in TiO2 host lattices. The Eg values obtained for Ce-Ti and pure Ce were 2.96 eV and 3.18 eV, respectively. Our photocatalytic results from the RhB dye decomposition in the presence of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocrystals resulted in a value of 2.17 eV. The absorption study revealed that the Ce-TiO2 nanocrystals were transparent in the visible region75,76,77. The absorption edge, determined from the peak maximum of the first derivative of the absorption plot, was at 263 nm (4.79 eV), which matches well with the standard bulk value band gap of Ce-Ti. Also, the steep rise of the absorption edge is an indication of the defect free structure of Ce-Ti nanocrystals78,79,80.

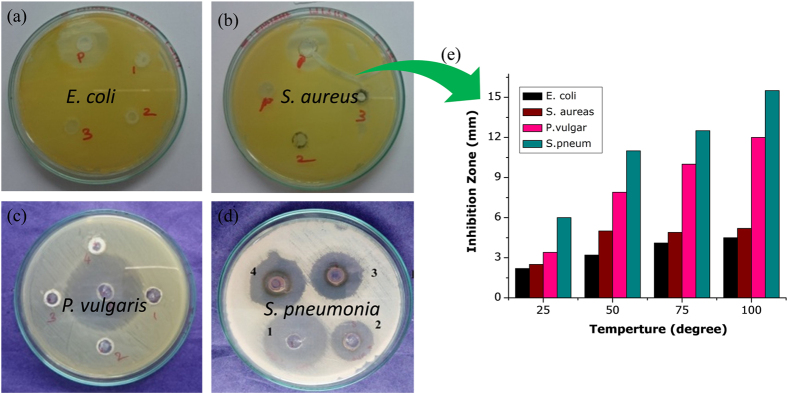

The antibacterial activity of the ceria-doped TiO2 nanoparticles was investigated using the well diffusion method. Approximately 20 mL of sterile molten Mueller Hinton agar (Hi Media Laboratories Pvt. Limited, Mumbai, India) was poured into the sterile petriplates. Triplicate plates were swabbed with the overnight culture (108 cells/mL) of pathogenic bacteria viz., E. coli, S. aureus, P. vulgaris and S. pneum. The solid medium was gently punctured with the help of cork borer to make a well. Finally, the nanoparticle samples (50 μg/mL) were added from the stock into each well and incubated for 24 hrs at 37 ± 2 °C. After 24 hrs of incubation, the zone of inhibition was measured and expressed as a diameter in mm81. The antimicrobial properties of ceria-doped TiO2 nanocrystals are presented in Fig. 9(a–e). The zone of inhibition of both Gram positive and Gram negative microbial strains against these studied materials clearly confirmed that the activity was directly proportional to the concentration of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocomposites. These results show that there is no inhibition on bacterial growth when the glass plate contained CeO2-doped TiO2 composites. Under UV light, a powder of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocomposites was used to examine its effects on the antibacterial activity for negative and positive bacteria. Gradually the zone of inhibition of both pathogens increased with increasing doping concentrations of TiO2. Among the microbial strains, Gram positive strains were more susceptible to the studied compounds than Gram negative strains. Gram negative microbial strains have thick cell wall membranes and lip polysaccharides, and these substances stop the penetration of the nanocomposite material into the cells82,83,84.

Figure 9. (a–e) Antibacterial performances of Ce-Ti-O2 nanocomposites were synthesized hydrothermally at 700 °C for 9 hrs.

In the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) study, different concentrations (5, 10, 25 and 50 μg/mL) of chosen nanoparticles were prepared with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and mixed with 100 μl/mL of nutrient broth and 50 μL of 24-hr old bacterial inoculum, and were allowed to grow overnight at 37 °C for 48 hrs. Nutrient broth alone served as a negative control. The whole setup in triplicate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 hrs. The MIC was the lowest concentration of the nanoparticles that did not permit any visible growth of bacteria during 24 hrs of incubation on the basis of turbidity. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) to avoid the possibility of misinterpretation related to the turbidity of insoluble compounds, if any, was determined by sub-culturing the MIC serial dilutions after 24 hrs in nutrient agar plates using a 0.01 mL loop and were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hrs. The MBC was regarded as the lowest concentration that prevents the growth of a bacterial colony in this media.

Conclusions

In summary, we report the synthesis and characterization of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocrystalline composites prepared hydrothermally. These composites were well-suited for preparing ceria-based titanium oxides with high surface areas (approaching 100 m2g−1) and cation stoichiometries close to 1:1. The composites were characterized by regular crystallites with well-defined compositions and narrow size distributions that had a cubic phase structure. This result was likely because of the small crystallite size effect. All of the results showed that the prepared nanocomposites displayed higher surface redox reactivities than their parent single oxides prepared using the same technique. The moderate degree of compositional heterogeneity of the specimens obtained in this way (surface enrichment of Ce) was attributed to the different relative speeds of the precipitation of Ce and Ti. The percentage decomposition of the most intense absorption peak at 579.93 nm after 1 and 2 hrs of irradiation was 93%. After 8 hrs irradiation in the presence of CeO2-doped TiO2 photocatalysts this value increased to 99.89%. The zone of inhibition of both Gram positive and Gram negative microbial strains against these studied materials confirmed that the activity was directly proportional to the concentration of CeO2-doped TiO2 nanocomposites. Addition of Ce, as well as the nature of surfactant used, played an important role in reducing the crystallite size. The FTIR, PL and XPS analyses confirmed the ceria-doped titania nanocrystals formed at room temperature.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kasinathan, K. et al. Photodegradation of organic pollutants RhB dye using UV simulated sunlight on ceria based TiO2 nanomaterials for antibacterial applications. Sci. Rep. 6, 38064; doi: 10.1038/srep38064 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge research funding from UNESCO-UNISA Africa Chair in Nanosciences/Nanotechnology Laboratories, College of Graduate Studies, University of South Africa (UNISA), Muckleneuk Ridge, Pretoria, South Africa, (Research Grant Fellowship of framework Post-Doctoral Fellowship program under contract number Research Fund: 139000). One of the authors (Dr. K. Kaviyarasu) is grateful for the Prof. M. Maaza, Nanosciences African network (NANOAFNET), Materials Research Department (MRD), iThemba LABS-National Research Foundation (NRF), Somerset West, South Africa. The Support Program and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of South Africa are thanked for their constant support, help and encouragement.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J. Kennedy, M. Maaza and M. Henini coordinated the technical work plan and manuscript. K. Kaviyarasu and E. Manikandan performed the antibacterial experiment and acquired the data. K. Kaviyarasu, M. Maaza and J. Kennedy processed the data and prepared the manuscript.

References

- Asahi R., Morikawa T., Ohwaki T., Aoki K. & Taga Y. Visible Light Photocatalysis in Nitrogen-Doped Titanium Oxides. Science. 293, 269–271 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjana V., Samdarshi S. K. & Singh J. Hexagonal Ceria Located at the Interface of Anatase/Rutile TiO2 Superstructure Optimized for High Activity under Combined UV and Visible-Light Irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 23899–23909 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu L., Peter Y. & Mao S. Increasing Solar Absorption for Photocatalysis with Black Hydrogenated Titanium Dioxide Nanocrystals. Science. 331, 746–750 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji P., Zhang J., Chen F. & Anpo M. Study of Adsorption and Degradation of Acid Orange on the Surface of CeO2 under Visible Light Irradiation. Appl. Catal. B. 85, 148–154 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Tang X., Mo C. & Qiang Z. Characterization and Activity of Visible-Light-Driven TiO2 Photocatalyst Co-doped with Nitrogen and Cerium. J. Solid State Chem. 181, 913–919 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Y. M., Lavik E. B., Kosacki I., Tuller H. L. & Ying J. Y. Defect and Transport Properties of Nanocrystalline CeO2-x. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 185–187 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Munoz Batista M. J., Goomez Cerezo M. N., Kubacka A., Tudela D. & Fernandez-Garcia M. Role of Interface Contact in CeO2-TiO2 Photocatalytic Composite Materials. ACS Catal. 4, 63–72 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Tong T. et al. Preparation of Ce-TiO2 Catalysts by Controlled Hydrolysis of Titanium Alkoxide Based on Esterification Reaction and Study on its Photocatalytic Activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 315, 382–388 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima A. & Honda K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature. 283, 37–38 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Li X., Hou M., Cheah K. & Choy W. Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Ce3+ −TiO2 for 2-Mercaptobenzothiazole Degradation in Aqueous Suspension for Odour Control. Appl. Catal. A. 285, 181–189 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kubacka A., Fernandez-Garcia M. & Colon G. Nanostructured Ti−M Mixed-Metal Oxides: Toward a Visible Light-Driven Photocatalyst. J. Catal. 254, 272–284 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Suil In. et al. Effective Visible Light-Activated B-Doped and B, N-Co-doped TiO2 Photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 13790–13791 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R. & Samdarshi S. Correlating Oxygen Vacancies and Phase Ratio/Interface with Efficient Photocatalytic Activity in Mixed Phase TiO2. J. Alloys Compd. 629, 105–112 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Zhu Y. & Meng M. Preparation, Formation Mechanism and Photocatalysis of Ultrathin Mesoporous Single-Crystal-Like CeO2 Nanosheets. Dalton Trans. 42, 12087–12092 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primo A., Marino T., Corma A., Molinari R. & Garcia H. Efficient Visible-Light Photocatalytic Water Splitting by Minute Amounts of Gold Supported on Nanoparticulate CeO2 Obtained by a Biopolymer Templating Method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6930–6933 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. & Liu Q. Preparation and characterization of titania photocatalyst co-doped with boron, nickel, and cerium. Mat. Lett. 62, 2589–2592 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q. Z., Su X. T., Huang Z. Y. & Ge C. C. Sol-gel auto-igniting synthesis and structural property of cerium-doped titanium dioxide nanosized powders. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 26, 915–921 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Xie J. et al. Preparation and Characterization of Monodisperse Ce-Doped TiO2 Microspheres with Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity. J. Colloids Surf. A. 372, 107–114 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G., Huang X., Liao X. & Shi B. One-Pot Synthesized of cerium-doped TiO2 mesoporous nanofibers using collagen fibers as the biotemplate and its application in visible light photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 9739–9746 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Y. M., Lavik E. B., Kosacki I., Tuller H. L. & Ying J. Y. Nonstoichiometry and Electrical Conductivity of Nanocrystalline CeO2-x. J. Electroceram. 1, 7–14 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. G. et al. Anatase TiO2, single crystals with a large percentage of reactive facets. Nature. 453, 638–642 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. G., Kuang Q., Jin M. S., Xie Z. X. & Zheng L. S. Synthesis of titania nanosheets with a high percentage of exposed (001) facets and related photocatalytic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3152–3153 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veerapandian M., Sadhasivam S., Choi J. H. & Yun K. S. Glucosamine functionalized copper nanoparticles: preparation, characterization and enhancement of antibacterial activity by ultraviolet irradiation. J. Chem. Eng. 209, 558–567 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Xiong Y., Lim B. & Skrabalak S. E. Shape-controlled synthesis of metal nanocrystals: simple chemistry meets complex physics? Angrew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 60–103 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li Y. F. & Huang C. Z. A one-pot green method for one-dimensional assembly of gold nanoparticles with a novel chitosan-ninhydrin bioconjugate at physiological temperature. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 4315–4320 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kaviyarasu K., Manikandan E., Paulraj P., Mohamed S. B. & Kennedy J. One dimensional well-aligned CdO nanocrystals by solvothermal method. J. Alloys & Comp. 593, 67–70 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kaviyarasu K., Sajan S., Selvakumar M. S., Augustine Thomas S. & Prem Anand D. A facile hydrothermal route to synthesize novel PbI2 nanorods. J. Phy. Chem. Sol. 73, 1396–1400 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. et al. CTAB assisted synthesis and photocatalytic property of CuO hollow microspheres. J. Sol. St. Chem. 182, 1088–1093 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., He J., Evans D. G., Zhu Y. & Duan X. Preparation characterization and photocatalytic activity of TiO2 formed from a mesoporous precursor. J. Por. Mat. 11(3), 131–139 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Nidhin M., Indumathy R., Sreeram K. J. & Nair B. U. Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles of Narrow Size Distribution on Polysaccharide Templates. Bul. Mat. Sci. 31, 93–96 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. A., Xian A. P., Cao L. H., Xie R. C. & Shangm J. K. Influence of Calcining Temperature on Photoresponse of TiO2 Film under Nitrogen and Oxygen in Room Temperature. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 134, 718–726 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Chiang K., Amal R. & Tran T. Photocatalytic Degradation of Cyanide using Titanium Dioxide Modified with Copper Oxide. Adv. Environ. Res. 6, 471–485 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. E., Ni X. M., Zheng H. G., Zhang X. J. & Song J. M. Fabrication of rod-like CeO2: characterization, optical and electrochemical properties. Solid State Sci. 8, 1290–1293 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. P. et al. Thermally stable Pt/CeO2 hetero-nanocomposites with high catalytic activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4998–4999 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phoka S. et al. Synthesis, structural and optical properties of CeO2 nanoparticles synthesized by a simple polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) solution route. Mater. Chem. Phys. 115, 423–428 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. S. et al. Synthesis of CeO2 nanorods via ultrasonication assisted by polyethylene glycol. Inorg. Chem. 46, 2446–2451 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy B. M., Katta L. & Thrimurthulu G. Novel nanocrystalline Ce1-xLaxO2-d (x = 0.2) solid solutions: structural characteristics and catalytic performance. Chem. Mater. 22, 467–475 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Singh K., Acharya S. A. & Bhoga S. S. Low temperature processing of dense samarium-doped CeO2 ceramics: sintering and intermediate temperature ionic conductivity. Ionics. 13, 429–434 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Sutradhar N. et al. Facile low temperature synthesis of ceria and samarium-doped ceria nanoparticles and catalytic allylic oxidation of cyclohexene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 7628–7637 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Subrata K. et al. Fabrication of catalytically active nanocrystalline samarium (Sm)-doped cerium oxide (CeO2) thin films using electron beam evaporation. J. Nanopart. Res. 14, 1040–1048 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. K. et al. The alteration of the structural properties and photocatalytic activity of TiO2 following exposure to non-linear irradiation sources. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 44, 173–184 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Tubchareon T., Soisuwan S., Ratanathammaphan S. & Praserthdam P. Effect of Na−, K−, Mg− and Ga dopants in A/B-sites on the optical band gap and photoluminescence behavior of [Ba0.5Sr0.5]TiO3 powders. J. Lumin. 142, 75–80 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kaviyarasu K. et al. Photoluminescence of well-aligned ZnO doped CeO2 nanoplatelets by a solvothermal route. Mat. Lett. 183, 351–354 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. Multi-type carbon doping of TiO2 photocatalyst. Chem. Phys. Lett. 444, 292–296 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Umebayashi T., Yamaki T., Itoh H. & Asai K. Analysis of electronic structures of 3d transition metal-doped TiO2 based on band calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 63, 1909–1920 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Gai Y. et al. Design of narrow-gap TiO2: a passivated codoping approach for enhanced photo electrochemical activity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 036402 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong P., Liu B., Wang Y., Pei H. & Yin S. Nonmetal sulfur-doped coral-like cobalt ferrite nanoparticles with enhanced magnetic properties. J. Mater. Res. 25, 2392 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Janke N., Bieberle A. & Weibmann R. Characterization of sputter-deposited WO3 and CeO2−x–TiO2 thin films for electrochromic applications. Thin Solid Films. 392, 134–141 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Toshiaki O. et al. Temperature Dependence of the Raman Spectrum in Anatase TiO2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 48, 1661–1668 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Fang F., Kennedy J., Manikandan E., Futter J. & Markwitz A. Morphology and characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by arc discharge. Chem. Phy. Lett. 521, 86–90 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Stylidi M., Kondarides D. I. & Verykios X. E. Pathways of solar light-induced photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous TiO2 suspensions. Appl Catal B. 40, 271–286 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Oman Z. & Nuryatini H. Synthesis, Characterization and Properties of CeO2-doped TiO2 Composite Nanocrystals. Mat. Sci. 19, 443–447 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kamat P. V., Das S., Thomas K. G. & George M. V. Ultrafast photochemical events associated with the photosensitization properties of a squaraine dye. Chem. Phys. Lett. 178, 75–79 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Kosanie M. M. & Trickovic J. S. Degradation of pararosaniline dye photoassisted by visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 149, 251–257 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Amita V. & Amish G. J. Structural optical photoluminescence and photocatalytic characteristics of sol-gel derived CeO2-TiO2 films. Ind. J. Chem. 48, 161–167 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R. et al. Promotional effect of fluorine on the selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over CeO2-TiO2 catalyst at low temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 289, 237–244 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kaviyarasu K. et al. Synthesis and characterization studies of NiO nanorods for enhancing solar cell efficiency using photon upconversion materials. Cer. Int. 42, 8385–8394 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y. et al. Exploring the effect of boron and tantalum codoping on the enhanced photocatalytic activity of TiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 351, 746–752 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Kaviyarasu K., Manikandan E., Nuru Z. Y. & Maaza M. Investigation on the structural properties of CeO2 nanofibers via CTAB surfactant. Mat. Lett. 160, 61–63 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Sayyar Z., Babaluo A. & Shahrouzi J. Kinetic study of formic acid degradation by Fe3+ doped TiO2 self-cleaning nanostructure surfaces prepared by cold spray. Appl. Surf. Sci. 335, 1–10 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima X. & Zhang C. R. Titanium dioxide photocatalysis: Present situation and future approaches. Chimie. 9, 750–760 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Zhenghua F. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of hierarchical flower-like CeO2/TiO2 heterostructures. Mat. Lett. 175, 36–39 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Kaviyarasu K. et al. Solution processing of CuSe quantum dots: Photocatalytic activity under RhB for UV and visible-light solar irradiation. Mat. Sci. & Eng. B. 210, 1–9 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Low J., Cheng B. & Yu J. Surface modification and enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of TiO2: a review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 392, 658–686 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- Anpo M. Use of visible light. Second-generation titanium dioxide photocatalysts prepared by the application of an advanced metal ion-implantation method. Pure. Appl. Chem. 72, 1787–1792 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Phanichphant S., Nakaruk A. & Channei D. Photocatalytic activity of the binary composite CeO2/SiO2 for degradation of dye. App. Sur. Sci. 387, 214–220 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M. R., Martin S. T., Choi W. & Bahnemann D. W. Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 95, 69–94 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Sajan C. et al. TiO2 nanosheets with exposed {001} facets for photocatalytic applications. Nano Res. 9, 3–27 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Fijushima A., Rao T. N. & Tryk D. A. Titanium dioxide photocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. Photochem. Rev. 1, 1–21 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Hao C. et al. Enhancement of photocatalytic properties of TiO2 nanoparticles doped with CeO2 and supported on SiO2 for phenol degradation. App. Sur. Sci. 331, 17–26 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Magdalane C. M. et al. Photocatalytic activity of binary metal oxide nanocomposites of CeO2/CdO nanospheres: Investigation of optical and antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. & Photobio. B: Bio. 163, 77–86 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. CeO2 doped anatase TiO2 with exposed (001) high energy facets and its performance in selective catalytic reduction of NO by NH3. App. Sur. Sci. 330, 245–252 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Irie H., Watanabe Y. & Hashimoto K. Nitrogen-concentration dependence on photocatalytic activity of TiO2-xNx powders. J. Phys. Chem. B. 97, 5483–5486 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Akple M. et al. Nitrogen-doped TiO2 micro sheets with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity for CO2 reduction. Chin. J. Catal. 36, 2127–2134 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra R. C. Synthesis and reactions of metal alkoxides. J. Non. Crys. Sol. 121, 1 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Wen J. et al. Photocatalysis fundamentals and surface modification of TiO2 nanomaterials. Chin. J. Catal. 36, 2049–2070 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Zhang J., Xiao C., Si Z. & Tan X. Solar photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in carbon-doped TiO2 nanoparticles suspension Sol. Energy. 82, 706–713 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Xiaofei Q., Dandan X., Lei G. & Fanglin D. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of TiO2/CeO2 core-shell nanotubes. Mat. Sci. Semi. Proc. 26, 657–662 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bae E. & Choi W. Highly Enhanced Photo reductive Degradation of Perchlorinated Compounds on Dye-Sensitized Metal/TiO2 under Visible Light. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 147–152 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation and adsorption of methylene blue via TiO2 nanocrystals supported on graphene-like bamboo charcoal. Appl. Sur. Sci. 358, 425–435 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Masoud N. et al. The antibacterial effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, Annals. Biol. Res. 3(7), 3671–3678 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Xin Li. et al. Engineering heterogeneous semiconductors for solar water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 2485–2534 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Angel E. et al. Green synthesis of NiO nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera extract and their biomedical applications: Cytotoxicity effect of nanoparticles against HT-29 cancer cells. J. Photochem. & Photobio. B: Bio. 164, 352–360 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghibi S. et al. Exploring a new phenomenon in the bactericidal response of TiO2 thin films by Fe doping: Exerting the antimicrobial activity even after stoppage of illumination. Appl. Surf. Sci. 327, 371–378 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.