Abstract

Introduction

Historically, Kenya has used various distribution models for long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets (LLINs) with variable results in population coverage. The models presently vary widely in scale, target population and strategy. There is limited information to determine the best combination of distribution models, which will lead to sustained high coverage and are operationally efficient and cost-effective. Standardised cost information is needed in combination with programme effectiveness estimates to judge the efficiency of LLIN distribution models and options for improvement in implementing malaria control programmes. The study aims to address the information gap, estimating distribution cost and the effectiveness of different LLIN distribution models, and comparing them in an economic evaluation.

Methods and analysis

Evaluation of cost and coverage will be determined for 5 different distribution models in Busia County, an area of perennial malaria transmission in western Kenya. Cost data will be collected retrospectively from health facilities, the Ministry of Health, donors and distributors. Programme-effectiveness data, defined as the number of people with access to an LLIN per 1000 population, will be collected through triangulation of data from a nationally representative, cross-sectional malaria survey, a cross-sectional survey administered to a subsample of beneficiaries in Busia County and LLIN distributors’ records. Descriptive statistics and regression analysis will be used for the evaluation. A cost-effectiveness analysis will be performed from a health-systems perspective, and cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated using bootstrapping techniques.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been evaluated and approved by Kenya Medical Research Institute, Scientific and Ethical Review Unit (SERU number 2997). All participants will provide written informed consent. The findings of this economic evaluation will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications.

Keywords: Economic evaluation, Insecticide-treated bed nets, Supply and distribution, Cost analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

It is the first study to look at the cost-effectiveness of parallel net distribution channels and coverage results that can be expected from each channel based on financial inputs.

Provide evidence on the costs and resources required to deliver LLINs using current distribution channels and to assist in determining the efficient allocation of resources.

The study is localised in one county of western Kenya; therefore, the results might not be representative or generalizable to all of Kenya or other countries.

Background

In Kenya, five channels of distributing long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets (LLINs) have been used historically in the implementation of malaria control programmes with variable results in population coverage.1–6 In 2004, when LLINs were distributed through the commercial retail sector and heavily subsidised social marketing schemes in rural shops and public health facilities, LLIN coverage was estimated at 7.1%.5 6 By 2005, coverage with LLINs increased to 23.5% with the provision of free LLINs in antenatal care and child health clinics in public health facilities.7 In 2011, LLIN coverage dramatically increased to 67% after free distribution of LLINs in a Ministry of Health (MoH) mass distribution campaign with the goal of universal coverage, defined as one LLIN per two people in each household.1–4 In addition, since 2001, heavily subsidised LLINs have been distributed through social marketing outlets in rural areas (ie, ∼600 000–800 000 nets annually).1 3 In 2012, the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP)/MoH began a concerted effort to scale up malaria community case management. Using community health volunteers to distribute nets, a continuous LLIN distribution pilot project was implemented in 2014–2015 in Samia, an administrative location in Funyula division of Busia County in western Kenya.

Post-campaign surveys after the rolling 2011–2012 universal coverage mass distribution demonstrated low LLIN usage among all age groups.8 For children <5 years of age, usage ranged from 28% to 59% across the different malaria epidemiological zones and 31% to 50% in the general population across zones.5 9 10 The proportion of persons using LLINs did not increase significantly after the 2011–2012 mass campaign compared with the 2010 Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey (KMIS), which showed that the proportions of children under 5 years of age and general population who slept under an LLIN the previous night was 42% and 39%, respectively.5 9 10

By mid-2014, only 34% of households nationally met the universal coverage indicator of one LLIN per two people.11 Access to nets, defined by attaining universal coverage at the household level, is directly associated with use of nets by both children under 5 years of age and all household members. In households that met universal coverage (ie, having at least one LLIN for every two people), 87% of children under 5 years of age slept under a net the previous night compared with 49% in households without universal coverage.7 Thus, a major part of the solution to increasing net use in Kenya is to increase the number of nets within a household to ensure universal coverage. Despite multiple functional distribution channels and massive investments, LLIN coverage still remains well below the Kenya National Malaria Strategy (NMS) 2009─2017 and WHO goals of having at least 80% of people living in malaria-risk areas using LLINs.2 5 9

Studies from various parts of Africa indicate that the use of LLINs has a beneficial effect on malaria transmission, severe malaria and mortality.12 13 Similarly, there are numerous studies demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of LLINs in different parts of the world and in various contexts.14–18 However, information is limited on the actual costs of parallel distribution channels in the same context and coverage results that can realistically be achieved from each channel based on financial inputs.19 In 2013, Kenya devolved responsibility for health service delivery from the central government to 47 county governments as mandated in the 2010 Constitution of Kenya. This major restructuring potentially creates challenges due to inconsistencies in practice, duplicate structures and may hamper malaria control.

In this new and evolving health services delivery context in Kenya, the NMCP/MoH, counties, donors and stakeholders require evidence-based cost-effectiveness data on LLIN distribution channels to make informed, rational decisions for programme implementation and targets. This study is intended to help provide the evidence required for decision-making. The goals of this economic evaluation are therefore to determine the actual cost of delivering a net to the end user in each channel and the coverage levels that can be achieved given a financial input. The economic evaluation results will help inform policy and programme implementation by establishing the costs and outcomes for each LLIN distribution channel in Kenya.

Objectives

The main objective of the economic evaluation is to assess the allocative efficiency of a limited budget to support implementation of LLINs as a prevention strategy and determine the most cost-effective mix of LLIN distribution channels that would maximise coverage for beneficiaries.

Specific objectives

Determine and compare the unit cost associated with distributing an LLIN to a beneficiary through the following distribution channels:

Universal coverage mass distribution campaigns;

Routine distribution through antenatal and child health clinics;

Continuous community distribution by community health volunteers;

Social marketing by community-based organisations through rural outlets;

Commercial retail outlets.

Determine and compare the proportion of coverage defined as the following:

Universal coverage (ie, one LLIN per two people per household);

At least one LLIN per household.

The principal health economic research question is: do the current LLIN distribution channels represent an efficient allocation of scarce resources?

Therefore, the specific health economics research questions are as follows:

What is the impact of the current LLIN distribution channels on health system costs?

What are the costs and outcomes of the five different LLIN distribution channels?

What are the main cost drivers in the distribution of LLINs?

Methods and design

Study design

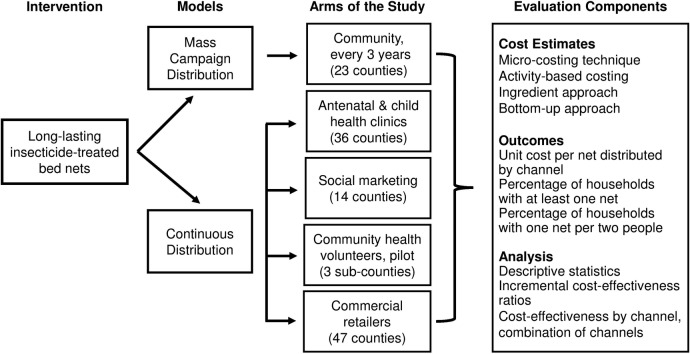

The study is a retrospective economic evaluation from the provider's perspective involving five arms to compare the costs and effectiveness of the LLIN distribution channels in Busia County, western Kenya. The arms of the study are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Concept map of economic evaluation of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets distribution channels in Busia County, Kenya.

Description of LLIN distribution channels (comparators)

The five different LLIN distribution channels that will be evaluated are briefly described here and illustrated in figure 1.

Universal coverage mass distribution campaigns which entail the distribution of LLINs to all households in endemic and epidemic-prone areas (ie, 23 counties) every 3 years. The campaign is planned and implemented by the NMCP/MoH with financial support from donors. The LLINs are procured by the NMCP/MoH and donors and distributed to health facilities in the 23 counties as part of the procurement contract. Prior to distribution, a household registration is undertaken whereby small teams of local MoH staff and community leaders register all households and the number of persons per household in a given geopolitical location or catchment area. The LLINs are distributed to health facilities and central storage points in each county based on the household registration. The head of the household or designated person comes to the designated health facility during the campaign time frame, which is generally 3–5 days, to collect the number of LLINs based on the number of persons registered in their household. One LLIN per two persons per household is provided free of charge to beneficiaries. In Kenya, there is no household distribution of LLINs during the campaign or after. Registered persons who do not come to the health facilities to collect LLINs do not receive nets. Households receive communications for both the household registration and campaign distribution dates through community meetings, local radio announcements, health facilities and other communication channels. The local MoH and county government leadership comprise the majority of staff for mass LLIN distribution campaigns. In the rolling 2014–2015 universal coverage mass distribution campaign, ∼12.3 million LLINs were distributed in 23 counties.5

Routine distribution of one free LLIN to every pregnant woman at the first antenatal clinic visit and to every child <1-year of age at the first immunisation visit in public and non-for-profit health facilities in endemic, epidemic-prone and seasonal transmission areas (ie, 36 counties). The distribution of LLINs via antenatal care and child health clinics is implemented by a non-governmental organisation (NGO) in coordination with the NMCP/MoH and with financial support from donors. All routine LLINs are procured through two NGO partners. All routine LLINs are transported, stored in regional warehouses and distributed to health facilities by the second NGO partner. The second NGO partner manages all aspects of the supply chain for LLINs in accordance with national policy and in coordination with the NMCP/MoH. In 2015, ∼3 million LLINs will be distributed to meet NMCP/MoH targets for routine antenatal care and child health clinic distribution.

Pilot continuous LLIN distribution project using community health volunteers to distribute vouchers for nets to community members in a portion of one county. The community health volunteers confirm the need for new LLINs at the household level, either because the household does not have enough LLINs for universal coverage or to replace worn, non-protective nets. The voucher is taken by the community member to a designated community health facility and redeemed for free LLINs. The pilot project was implemented in three sub-counties in Busia County, western Kenya. The pilot was implemented by an NGO partner in coordination with the NMCP/MoH and with financial support from donors. All LLINs were procured, transported, stored and distributed to health facilities by the NGO partner. The NGO partner managed all aspects of the voucher process and LLIN supply chain in coordination with the NMCP/MoH. The community health volunteers are each assigned ∼50 households in a village and are linked to health dispensaries or health centres for reporting purposes, commodity supply (eg, malaria rapid diagnostic tests and medications for case management) and supervision by the community health extension worker. The community health volunteers do not get a formal salary but receive a modest stipend from the county government or NGO partners.3 Approximately 100 000 nets were intended for the continuous community distribution pilot project from October 2014 to March 2015.

Social marketing of heavily subsidised LLINs in rural shops and by community-based organisations in endemic, epidemic-prone and seasonal transmission areas, including Busia County. The distribution of socially marketed LLINs is a partnership between a primary NGO partner, multiple community-based organisations, rural outlets and the NMCP/MoH and with financial support from donors. All socially marketed LLINs are procured, transported, stored and distributed to the sellers by the primary NGO partner. The NGO partner manages all aspects of the supply chain for LLINs in coordination with the NMCP/MOH. The rural shops and community-based organisations use communications mechanisms such as community gatherings, local radio and TV shows and advertisements, competitions, drama and theatre to attract customers. In 2015, the target price for a socially marketed LLIN was ∼US$1.50 to the customer. Approximately 600 000–800 000 LLINs are sold via social marketing channels annually.

Commercial, for-profit-sector retailers stock and sell LLINs at market prices throughout Kenya. Prices vary widely based on geographic location, target market, manufacturer, brand, size, material and other factors.

Cost data will be collected retrospectively from a provider's perspective from health facilities, NMCP/MoH, NGO partners, donors, stakeholders, distributors and the Kenya Medical Supply Agency (KEMSA). KEMSA is the central medical store and provides supply chain management of malaria commodities from the national to facility levels. Data on outcomes will be triangulated from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of over 6300 households, a cross-sectional survey administered to a subsample of beneficiaries in Busia County, and distributors' records. The evaluation will involve comparing the costs of distribution and outcomes for each distribution channel. For cost estimates, we will use a bottom-up approach, combining activity-based costing (ABC), ingredient approach and budget expenditure data.20 21 The bottom-up approach is an established micro-costing technique that has been successfully applied to diverse settings in corporate and healthcare sectors.20–24 In contrast to traditional costing systems, in which direct, indirect and overhead costs are aggregated and assigned proportionally based on unit volume produced or services delivered, micro-costing assigns costs more accurately by delineating specific services or processes responsible for actual resource consumption. Resources will be organised into cost categories as summarised in table 1. Cost drivers from each cost category will be quantified and unit cost per net distributed will be calculated.

Table 1.

Description of key categories of costs and sources

| Cost category | Information source |

|---|---|

| Labour | |

| Disaggregated into cadre and type | MOH, sub-county health offices, partner records and staff interviews |

| Transport | |

| Vehicles | MOH, sub-county health offices, partner records, retailers and staff interviews |

| Motorbikes | |

| Bicycles | |

| Fuel | |

| Maintenance | |

| Hired vehicles | |

| Equipment | |

| Personal protective | MOH, sub-county health offices, partner records and staff interviews |

| Mobile phones | |

| Laptops | |

| Other equipment | |

| Supplies | |

| LLINs | MOH, sub-county health offices, partner records, donor records and staff interviews |

| Mobile phone and talk time | |

| Other supplies | |

| Other inputs | |

| Print and radio advertisements | MOH, county health offices, implementing partners records, donors and staff interviews |

| Meeting space | |

| Community mobilisation | |

| Warehousing | |

| Security | |

| Waste management | |

| Overhead costs of partners, retailers | |

| Other inputs | |

LLINs, long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets; MOH, Ministry of Health.

Cost data will be obtained from financial reports and budgets of NGO partners, NMCP/MoH, KEMSA and Busia County Directorate of Health, community-based organisations, Ministry of Finance/National Treasury and other available sources. To ease understanding and facilitate comparisons, costs in Kenya shillings will be converted into US dollars depending on the currency of the original expenditure and the average Kenya Central Bank exchange rate for the period of the expenditure.

Sample size calculations

For outcome data, a cross-sectional survey will be conducted in randomly selected households in Busia County to collect data on coverage and source of nets. A list of households will be obtained from the community unit registers. The sample size was calculated assuming a universal coverage of 40% (defined as one LLIN per two persons per household). The least effect size in LLIN coverage levels expected from the distribution channels is 15%. This will result in a minimum sample size of 456 households to be surveyed assuming a 5% margin of error and 80% power to detect differences in coverall levels. An additional 30% to account for refusals and absentees during the survey will be added to obtain a target sample size of 592 households.

Interviewers will explain to all participants that involvement in the study is voluntary and that they have the right to withdraw at any point in time and ask any questions. Information about the study will be read to all participants and provided in a hard copy. All consenting participants will be asked to sign two standard consent forms (ie, one for the interviewee and one retained by the interviewer).

Effectiveness measures

The main effectiveness measure is the percentage of persons using an LLIN for malaria prevention in at-risk areas; the NMCP/MoH and WHO target for this indicator is at least 80% of the population.5 Two additional effectiveness measures will be based on the WHO and the Roll Back Malaria Monitoring and Evaluation Reference Group (RBM MERG) indicators used for monitoring achievement of universal coverage: percentage of households with universal coverage with LLINs (ie, one LLIN per two persons per household) and percentage of households with at least one LLIN.5

The main health economics-related outcomes are the total and unit cost of distributing an LLIN through each of the five current distribution channels. Additional health economics outcomes are the mean and median cost by distribution channel categorised by quartiles and household outcome, the total and mean cost by distribution channel and by cost category and the incremental cost of the distribution channel compared with other channels. Savings will be recorded as negative incremental costs.

Economic evaluation

The cost and effectiveness of the outcomes of the five distribution channels will be compared with each other and analysed using cost-effectiveness methods.15–19 To analyse the effectiveness of the distribution channel with regard to the cost and outcome measures, descriptive statistics and a generalised linear regression model will be used because cost data are usually not normally distributed.15–18 The analysis will include comparison of the different distribution channels as well as a multilevel analysis focusing on cost categories.

Cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated based on the primary outcome measure in relation to a range of health economics outcomes (eg, total, mean, median and incremental costs) for each LLIN distribution channel. Financial costs will be adjusted to obtain economic costs and assign costs to donated items as well as time of volunteers included in some of the distribution channels. The LLIN distribution channels are generally expected to perform for more than 1-year and the capital items purchased to deliver the LLINs have a life expectancy in excess of 1-year. Similarly, LLINs are intended to last for 3 years in field conditions.19 25 26 Therefore, capital costs will be expressed as an annual equivalent. Capital inputs that will be annualised are LLINs, vehicles and equipment using 3.5% as a discounting rate.15–19

Cost-effectiveness will be calculated for each comparison and will be expressed as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). Mass campaigns are by far the largest channel by volume and assumed to be the least expensive and most efficient channel for distributing LLINs in Kenya; therefore, the campaign distribution channel will be used as a baseline for the comparative analysis. Owing to time and resource constraints, the economic evaluation (ie, cost-effectiveness component) will be performed from a health systems perspective (ie, distributors and donors). ICERs will be estimated using bootstrapping techniques and graphically presented on cost-effectiveness planes.21–24 For comparisons and ease of understanding, costs will generally be quoted in US dollars.

Cost estimates inevitably involve assumptions and uncertainty. Therefore, we will carefully identify critical assumptions and areas of uncertainty and re-estimate the results using different assumptions to test the sensitivity of the results and conclusions due to such change. We will perform both one-way and multi-way sensitivity analysis in order to assess the robustness of the results and examine the effect of common assumptions and uncertain variables on the evaluation findings.27 28 An a priori analysis plan was developed and agreed on prior to the initiation of data collection and analysis.

Discussion and conclusion

Although there is robust literature around LLINs as the main malaria prevention and control strategy, there are very limited data on the cost-effectiveness of LLIN distribution channels in field settings. Therefore, NMCPs, stakeholders and donors have limited information on which to base policy and plan programmatic implementation to meet national and international LLIN coverage target indicators. This economic evaluation is intended to provide the NMCP/MoH, partners, stakeholders and donors with evidence on the costs and resources required to deliver LLINs using current distribution channels and to assist in determining the efficient allocation of resources to meet target outcome measures.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. President's Malaria Initiative, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This paper is published with the permission of Director KEMRI.

Footnotes

Contributors: EG, SK and VW conceived the study protocol and drafted the first manuscript. LN assisted in the design of the study, in particular the economic assessments, and in the drafting of the manuscript. MD, PO and AMB contributed to the drafting of the manuscript.

Funding: United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Disclaimer: The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CDC, USAID or USA Government. The funder was not involved in the design of the study, and nor did they contribute to the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Kenya Medical Research Institute, Scientific and Ethical Review Unit (SERU number 2997).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors shall share the data with interested parties.

References

- 1.Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). DFID's Contribution to the Reduction of Child Mortality in Kenya. Report No. 33 London: ICAI, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Recommendations for achieving universal coverage with long-lasting insecticidal nets in malaria control. Geneva: WHO, 2014. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/who_recommendations_universal_coverage_llins.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 3. U.S. President's Malaria Initiative-Kenya. Malaria Operational Plan FY2015. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, 2014. https://www.pmi.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/malaria-operational-plans/fy-15/fy-2015-kenya-malaria-operational-plan.pdf?sfvrsn=3.

- 4.UN. The Millennium Development Goals Report New York: United Nations, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. National Malaria Strategy 2009–2017. Nairobi: Division of Malaria Control, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. 2010 Kenya Malaria indicator survey. Division of malaria control. Nairobi: Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Population Services International (PSI).Kenya (2007): malaria TRaC study evaluating bed net ownership and use among pregnant women and children under 5 (years), third round. Nairobi: PSI, 2008. http://files.givewell.org/files/DWDA%202009/PSI/Kenya%202007%20Malaria.pdf.

- 8.Ministry of Public Health & Sanitation. Evaluation of the 2011 mass long lasting insecticide treated net (LLIN) distribution campaign, phase 1 and 2 report 2012.

- 9.WHO/RBM (2005) Working Group for Scaling-up Insecticide-Treated Nets. Scaling up insecticide-treated netting programs in Africa: a strategic framework for National action. Geneva: WHO/RBM, 2005Roll Back Malaria 2005–2015. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grabowsky M, Nobiya T, Selanikio J. Sustained high coverage of insecticide-treated bednets through combined Catch-up and Keep-up strategies. Trop Med Int Health 2007;12: 815–22. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Bureau of Statistics-Kenya and ICF International. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Rockville, Maryland, USA: KNBS and ICF International, 2015. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR308/FR308.pdf.

- 12.Binka F, Indome F, Smith T. Impact of spatial distribution of permethrin-impregnated bed nets on child mortality in rural northern Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawley WA, Phillips-Howard PA, ter Kuile FO et al. Community-wide effects of permethrin-treated bed nets on child mortality and malaria morbidity in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;68:121–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolaczinski J, Hanson K. Costing the distribution of insecticide-treated nets: a review of cost and cost-effectiveness studies to provide guidance on standardization of costing methodology. Malaria J 2006;5:37 10.1186/1475-2875-5-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pulkki-Brannström AM, Wolff C, Brännström N et al. Cost and cost effectiveness of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets—a model-based analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2012;10:5 10.1186/1478-7547-10-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson K, Kikumbih N, Armstrong Schellenberg J et al. The cost-effectiveness of social marketing of insecticide-treated nets for Malaria control in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:269–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiseman V, Hawley WA, ter Kuile FO et al. The cost-effectiveness of permethrin-treated bed nets in an area of intense malaria transmission in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;68(Suppl 4):161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster J, Lines J, Bruce J et al. Which delivery systems reach the poor? Equity of treated nets, untreated nets and immunisation to reduce child mortality in Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:709–17. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70269-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith Paintain L, Awini E, Addei S et al. Evaluation of a universal long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) distribution campaign in Ghana: cost effectiveness of distribution and hang-up activities. Malar J 2014;13:71 10.1186/1475-2875-13-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cianci F, Sweeney S, Konate I et al. The cost of providing combined prevention and treatment services, including ART, to female sex workers in Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e100107 10.1371/journal.pone.0100107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drummond M, McGuire A. Economic evaluation in health care, merging theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Salomon JA et al. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publication, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnard SS et al. Economic evaluations in clinical trials. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publication, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagnon NF, Pinder M, Tchicaya E F et al. To assess whether addition of pyriproxyfen to long-lasting insecticidal mosquito nets increases their durability compared to standard long-lasting insecticidal mosquito nets: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16(1):195 10.1186/s13063-015-0700-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilian A, Koenker H, Obi E et al. Field durability of the same type of long-lasting insecticidal net varies between regions in Nigeria due to differences in household behaviour and living conditions. Malar J 2015;14:123 10.1186/s12936-015-0640-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briggs A, Sculpher M, Buxton M. Uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care technologies: the role of sensitivity analysis. Health Economics 1994;3(2):95–104. 10.1002/hec.4730030206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs A. Economics notes: handling uncertainty in economic evaluation. BMJ 1999;319(7202):120 10.1136/bmj.319.7202.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]