Abstract

Objective

Peer facilitators play an important role in determining the success of many support groups for patients with medical illnesses. However, many facilitators do not receive training for their role and report a number of challenges in fulfilling their responsibilities. The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the effects of training and support programmes for peer facilitators of support groups for people with medical illnesses on (1) the competency and self-efficacy of group facilitators and (2) self-efficacy for disease management, health outcomes and satisfaction with support groups among group members.

Methods

Searches included the CENTRAL, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science databases from inception through 8 April 2016; reference list reviews; citation tracking of included articles; and trial registry reviews. Eligible studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in any language that evaluated the effects of training programmes for peer facilitators compared with no training or alternative training formats on (1) competency or self-efficacy of peer facilitators, and (2) self-efficacy for disease management, health outcomes and satisfaction with groups of group members. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used to assess risk of bias.

Results

There were 9757 unique titles/abstracts and 2 full-text publications reviewed. 1 RCT met inclusion criteria. The study evaluated the confidence and self-efficacy of cancer support group facilitators randomised to 4 months access to a website and discussion forum (N=23; low resource) versus website, discussion forum and 2-day training workshop (N=29). There were no significant differences in facilitator confidence (Hedges' g=0.16, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.71) or self-efficacy (Hedges' g=0.31, 95% CI −0.24 to 0.86). Risk of bias was unclear or high for 4 of 6 domains.

Conclusions

Well-designed and well-conducted, adequately powered trials of peer support group facilitator training programmes for patients with medical illnesses are needed.

Trial registration number

CRD42014013601.

Keywords: Support groups, EDUCATION & TRAINING (see Medical Education & Training), systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review to evaluate the effects of training and support programmes for peer facilitators of support groups for people with medical illnesses on (1) the competency and self-efficacy of group facilitators, and (2) self-efficacy for disease management, health outcomes and satisfaction of group members.

Important strengths of our systematic review include a broad search strategy, well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and rigorous data coding and reporting as outlined by Cochrane and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

A limitation was that we only identified one small trial and were not able to draw conclusions about the effects of peer facilitator training programmes.

Illness-based support groups bring together people who face similar disease-related challenges to give and receive emotional support and exchange disease-related information, sometimes in the form of structured educational activities.1–3 These groups can be configured in a variety of ways. They may be held face-to-face, online or via teleconference, they may be led by professionals or peers, and they may have a structured or unstructured format.1–3

Many people with chronic medical illnesses join support groups in order to better cope with the emotional and practical challenges of their disease.1–3 A number of studies have assessed the benefits of participating in support groups for common medical diseases, including cancer.4–6 Participants in these studies have reported a number of benefits, such as obtaining emotional support, receiving information about their disease and treatments, and learning how other patients have coped with the condition. They have also reported that support groups help decrease isolation, foster a sense of community and instil hope about the future.

In the case of many common medical diseases, support groups are offered by the healthcare system and are organised and delivered by professionals who are knowledgeable about the condition. Peer-led support groups, however, are a less resource-intensive alternative that could potentially reach more patients, with the added benefit of having group leaders who may share important experiences with group members.7 In some settings, such as in rare diseases, professionally led support groups are typically not available or readily accessible, and peer-led support groups often emerge through grassroots efforts.8 9

Support group facilitators play an important role in determining the success of a group.10 11 Many support group facilitators, however, do not receive training for their role and report a number of challenges in fulfilling their responsibilities.10 11 These challenges may include a lack of training and other resources; a lack of support from healthcare professionals; difficulty dealing with problematic group members; difficulty dealing with the worsening health and death of group members; difficulty finding back-up or replacement facilitators, and struggles to sustain the group.10 11

Formal training of peer support group facilitators could potentially address some of these concerns and could improve the experiences of group facilitators and members. No systematic reviews have examined the effects of training and support programmes for peer facilitators of support groups for people with medical illness. Thus, the objective of the present systematic review was to evaluate the effect of training and support programmes for peer facilitators of support groups for people with medical illnesses on (1) the competency and self-efficacy of group facilitators, and (2) self-efficacy for disease management, health outcomes and satisfaction with the support group experience among group members.

Methods

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42014013601), and was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.12

Search strategy

The CENTRAL, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science databases were initially searched from inception on 8 September 2014 and updated on 8 April 2016. A medical librarian developed the search strategy and performed the search. No restrictions by date or language or publication were used. The complete search strategy can be found in online supplementary file 1. In addition to database searching, we manually searched the reference lists of included publications and tracked their citations using Google Scholar.13 We also searched multiple trial registries, including ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), ISRCTN (http://www.isrctn.com) and the WHO registry search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch) from inception to 10 June 2016.

bmjopen-2016-013325supp.pdf (89KB, pdf)

Publication selection

The results of the search were downloaded into the citation management database RefWorks (RefWorks-COS, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), and duplicate references were identified and removed. Following this, references were transferred into the systematic review software DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). Using this software, we then assessed the eligibility of each publication through a two-stage process. First, two investigators independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of publications that were identified through the search strategy. If either investigator deemed an abstract potentially eligible based on the inclusion criteria, then a full-text review was completed. Disagreements after full-text review were resolved by consensus, with a third investigator consulted if necessary.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of training and support programmes for peer facilitators of illness-based support groups reported in any language were eligible for inclusion. For the purpose of this study, peer facilitator training and support programmes were defined as formal programmes designed to provide facilitators or potential facilitators of support groups with the knowledge to facilitate a support group, the interpersonal and other skills to do this, or ongoing emotional and practical support. Since the responsibilities of support group facilitators vary, training and support programmes could include a number of components aimed at developing the skills related to these responsibilities. The programmes could also vary in length, as well as in the instructional methods and techniques used. Training or support programmes that included both peer and professional facilitators, who facilitated groups as part of their professional responsibilities, were included. Training programmes for only professional group facilitators, however, were not eligible for inclusion.

We only included trials of training and support interventions for peer facilitators of support groups for people with medical illness. To be considered a peer-facilitated support group for people with medical illness, the activities of the group had to include the giving and receiving of emotional and practical support. They could also include educational activities, but a group that only followed a structured learning curriculum with a defined beginning and end (eg, a self-management programme) was not considered a support group. A group that was designed to be ongoing (or could be used in that way), but was time-limited for the purposes of a research study, was considered a support group. Activities of a support group could take place in person, online or via teleconference, but had to include ongoing real-time interaction between group members. Groups that provided psychotherapy were not considered a support group. Second, membership criteria of the group had to include having a particular disease (eg, diabetes) or type of disease (eg, a rare disease) or being a survivor of a disease (eg, cancer). Training programmes for peer facilitators of groups designed for people with mental health disorders were not eligible for inclusion.

Eligible comparators included no training comparators or alternative training approaches. Eligible RCTs had to assess outcomes that reflected (1) the competency or self-efficacy of group facilitators, or (2) self-efficacy for disease management, health outcomes or satisfaction with the support group experience among members of the support groups of the facilitators in the trial.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Two investigators independently extracted data from included RCTs and entered it into a standardised Excel spreadsheet. A complete list of extracted variables is provided in online supplementary file 2. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, with a third investigator consulted if necessary. The same two investigators also independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (see online supplementary file 3).14 Again, discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and a third investigator was consulted as necessary. Since only one eligible RCT was identified, there was no pooling of results.

Results

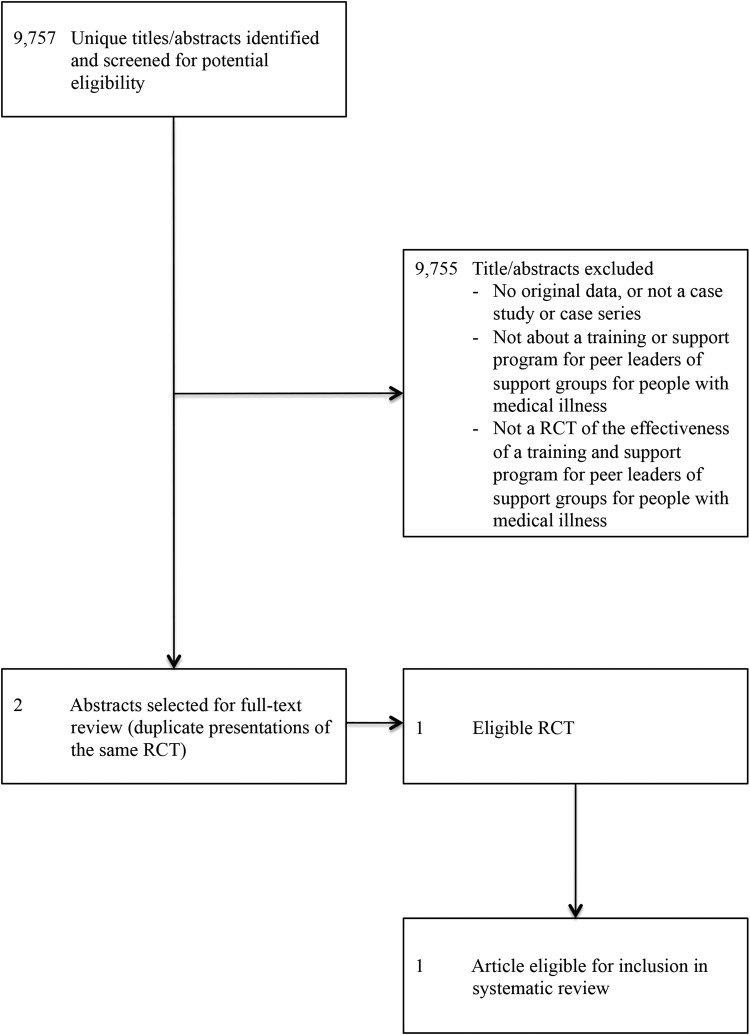

The database search yielded 9757 unique titles and abstracts. Of these, 9755 were excluded after title and abstract review, leaving two conference abstracts for full-text review.15 16 Both abstracts reported results from the same RCT. Since we were not able to locate a full report for this RCT at the time of our initial database searches, we contacted the authors. They provided us with a full report, which was subsequently published.17 The RCT met inclusion criteria and was included in the systematic review. No additional eligible studies were identified via manual searching of the reference list of the included publication, by searching trial registries or by citation tracking. See figure 1 for the PRISMA flow chart.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart. RCT, randomised controlled trial; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Description of included RCT

The included RCT enrolled individuals who were currently leading a support group for adults with cancer and/or caregivers in New South Wales, Australia.17 Support group facilitators were stratified based on gender, geographical location and type of group (eg, general cancer, specific cancer) and block randomised to one of two 4-month long interventions: (1) low resource, which included access to a website and discussion forum only, or (2) high resource, which included access to the website and discussion forum plus face-to-face training. The website was designed to provide facilitators with basic theoretical and practical information on facilitating a support group. The websites in the low-resource and high-resource interventions were the same, but the discussion forums were separated in order to prevent contamination. The training for facilitators in the high-resource intervention involved a 2-day group workshop that aimed to ‘improve confidence in the facilitator role, group facilitation skills, knowledge of group dynamics, understanding of boundaries, and awareness of self-care and burnout’. The workshop was led by an academic researcher and two experienced cancer support group facilitators. Participants in the workshop also received a DVD and manual with examples of how they might address a number of possibly challenging support group scenarios.

At the beginning and end of the 4-month intervention period, group facilitators in both trial arms completed a modified version of the Group Leader Self-Efficacy Instrument (GLSI) and the Group Leader Challenges Scale (GLCS). The modified GLSI is a 27-item self-report questionnaire that assesses self-efficacy for performing group facilitator skills on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).17 Higher scores on the GLSI indicate a higher degree of self-efficacy. The GLCS is a 26-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the confidence of group facilitators in their (1) ability to execute tasks beyond those of a typical group facilitator, (2) self-care and (3) specific issues related to cancer support groups.17 It also uses a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a higher degree of confidence. No outcomes were collected for members of support groups facilitated by participants in the trial.

Altogether, 30 group facilitators were randomised to the low-resource intervention and 35 to the high-resource intervention. Of these, 23 facilitators in the low-resource arm and 29 in the high-resource arm completed postintervention questionnaires and were included in analyses. Facilitators randomised to the two trial arms included people affected by cancer, as well as healthcare professionals who may or may not have been affected by cancer. Results for facilitators affected by cancer and not affected by cancer were not reported separately. As shown in table 1, there were no statistically significant differences between patients randomised to the low-resource and high-resource arms, although scores were higher for the high-resource arm for self-efficacy (Hedges' g=0.31, 95% CI −0.24 to 0.86) and confidence (Hedges' g=0.16, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.71). A comparison of participants in the high-resource and low-resource groups who provided data preintervention (high resource N=33; low resource N=29) to those who provided data postintervention (high resource N=29; low resource N=23) suggested similar and small post-trial minus pretrial positive differences in confidence in both groups and similar, small negative differences in both groups in self-efficacy.

Table 1.

Summary of randomised controlled trial included in systematic review

| Author, year, country | Funding source | Population and recruitment | Comparison | Number of participants randomised | Number of participants analysed | Intervention duration | Outcomes: Hedges' g (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zordan,17 2015, Australia | Australian Research Council | Cancer support group facilitators recruited via email through cancer organisations and using a ‘snowballing technique’ | Low resource: website and discussion forum only High resource: website, discussion forum and 2-day training workshop supported by DVD and manual |

Low resource: 30 High resource: 35 |

Low resource: 23 High resource: 29 |

4 months | GLSI: Hedges’ g=0.31 95% CI −0.24 to 0.86 GLCS: Hedges’ g=0.16 95% CI −0.39 to 0.71 |

*Positive values reflect greater self-efficacy (GLSI) and greater confidence (GLCS) for group facilitators in the high-resource intervention.

GLCS, Group Leader Challenges Scale; GLSI, Group Leader Self-Efficacy Instrument.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias ratings are shown in table 2. Risk of bias was rated ‘unclear’ for sequence generation and allocation concealment. Risk of bias was rated ‘high’ for blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors. All other risk of bias domains were rated ‘low’.

Table 2.

Assessment of risk of bias of RCT included in systematic review

| Cochrane risk of bias tool domains* | Review authors’ judgement | Support for review authors’ judgement |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence generation | Unclear | Authors reported that leaders were stratified based on gender, geographical location and type of group, and block randomised by a statistician. They did not provide information on how the randomisation sequence was generated. |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear | No information provided on allocation concealment method. |

| Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors | High | Blinding of participants and personnel was not possible due to nature of the intervention. Outcomes were self-reported by participants, who were not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data | Unclear | Approximately 20% missing data in both trial arms and not included in final analyses. |

| Selective outcome reporting | Low | Authors reported small, non-significant effect sizes for included outcomes. In addition, although not a prespecified outcome of the systematic review, they reported emotional distress, which was higher (non-significant) in the high-resource arm. |

| Other bias | Low | None |

*See online supplementary file 3 for domain descriptions. Domains are scored as ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘uncertain’ risk of bias. Risk of bias ratings were based only on published information.

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Discussion

The present systematic review did not identify any trials that compared training and support programmes for peer facilitators of disease-based support groups to no training comparators. It identified only one RCT that evaluated the effects of alternative training programme resources.17 That study evaluated the confidence and self-efficacy of cancer support group facilitators randomised to 4-month long high-resource (website, discussion forum, 2-day face-to-face training) and low-resource (website, discussion forum) interventions. No statistically significant differences were reported between the two groups for either group facilitator self-efficacy or confidence. Outcomes were not collected for members of the support groups of the facilitators.

There are important methodological considerations, however, that limit the ability to confidently draw conclusions about the potential effects of support group facilitator training programmes from the trial. One is that the sample size was very small. A total of 65 patients were randomised, and data from only 52 who completed postintervention assessments were analysed. To achieve 80% power for a small (Hedges' g=0.20) or medium (Hedges' g=0.50) effect size, 788 and 128 patients, respectively, would have been needed. A second is that the study was rated as having unclear risk of bias related to sequence generation, allocation concealment, and incomplete outcome data and high risk of bias related to blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors.

There are also several issues regarding the design of the intervention and the trial that should be considered when conducting trials on training programmes for support group facilitators in the future. First, trial participants included both group facilitators affected by cancer and healthcare professionals who may or may not have been affected by cancer. Peer and professional support group facilitators may have different training and support needs, although research on this topic is limited.11 18 Future studies should consider the possibility of targeting training to peer or professional group leaders.

Second, the information that was provided in the published trial report and a related article19 did not include important information that would be necessary to attempt to replicate the training programme and trial. For example, the authors described that participants in the training arm of the trial participated in one of three 2-day group workshops, but relatively little information was provided on the conduct of the workshops, when they occurred, or how participants were selected for each of the three workshops. The authors reported that workshops incorporated ‘readings, didactic lectures, the DVD and manual, role-plays and group discussion’,19 but no information was provided on how the sessions were structured, and only limited information was provided on the content. The authors did not indicate at what time during the 4-month long intervention period the 2-day workshops occurred, the length of each workshop day, or whether the days took place sequentially or were spaced apart. Learning and retention is improved when learning is repeated and spaced over time, and it is possible that training sessions spaced over time with opportunities to practice new skills could be more effective than one-shot programmes.20

Finally, the trials compared the confidence and self-efficacy of support group facilitators randomised to a low-resource intervention that included only access to a website and chat forum versus the website and chat forum plus the 2-day workshop. However, as many support group facilitators do not receive any training for their role, it would be useful to know how each of these compares to no training at all.

The growing number of people with one or more chronic medical illnesses, combined with increasingly limited healthcare resources, has made it difficult for healthcare providers and patient organisations to provide the support that people with chronic diseases need in order to deal with their condition. As such, many patients turn to support groups to help them cope with and manage their disease.1–3 Peer-led support groups are becoming increasingly popular as a less resource-intensive alternative that could potentially reach more patients and they could free professional resources for patients with more intense psychosocial needs.7

However, there are some important limitations of many current support groups. Many patients are not able to access groups, particularly in rare diseases, and many peer-led groups are not effectively sustained due to factors such as the health of the facilitator or other shortcomings that could be potentially addressed via training.21 22 Training programmes for peer facilitators of support groups could improve the availability of support groups by giving people with chronic diseases the skills they need to set up groups where none exists. In addition, these training programmes could increase the effectiveness of support groups by teaching support group facilitators how to organise and structure support groups, as well as how to manage group dynamics and difficult group members. More research is needed, however, to better understand options available for providing training to peer facilitators of support groups and to determine if they achieve their desired effects.

In summary, this systematic review found that there is insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of training and support programmes for peer facilitators of disease-based support groups and whether they improve the (1) the competency and self-efficacy of group facilitators, and (2) self-efficacy for disease management, health outcomes and satisfaction with support group experiences among group members. Well-designed and well-executed trials that assess whether training and support programmes for peer facilitators of support groups improve outcomes among group facilitators and group members are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Linda Slater, MLIS, John W. Scott Health Sciences Library, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Scleroderma Support Group Project Advisory Team Members include: Kerri Connolly, The Scleroderma Foundation, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA; Laura Dyas, The Scleroderma Foundation Michigan Chapter, Southfield, Michigan, USA; Stephen Elrod, The Scleroderma Foundation Southern California Patient Group, Los Angeles, California, USA; Catherine Fortune, The Scleroderma Society of Canada Ontario Patient Group, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Karen Gottesman, The Scleroderma Foundation, Los Angeles, California, USA; Anna McCusker, The Scleroderma Society of Canada and the Scleroderma Society of Ontario, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Michelle Richard, The Scleroderma Society of Canada Nova Scotia Patient Group, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; Robert Riggs, The Scleroderma Foundation, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA; Maureen Sauve, The Scleroderma Society of Canada and the Scleroderma Society of Ontario, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Nancy Stephens, The Scleroderma Foundation Michigan Patient Group, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Contributors: VCD, STG, LAK, JB, GE-B, AK, VLM, BDT and SSGPAT contributed to the conception and design of the systematic review. VCD, STG, LAK, JB and BDT were involved in the acquisition of data. VCD, STG and BDT analysed the data. VCD, STG, LAK, JB, GE-B, AK, VLM, BDT and SSGPAT interpreted the results. VCD and BDT drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical revisions and approved submission of the final manuscript. BDT is the guarantor.

Funding: VCD is supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Doctoral Award. STG is supported by a CIHR Master's Award. BDT receives support from an Investigator Award from the Arthritis Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Kerri Connolly, Laura Dyas, Stephen Elrod, Catherine Fortune, Karen Gottesman, Anna McCusker, Michelle Richard, Robert Riggs, Maureen Sauve, and Nancy Stephens

References

- 1.Lieberman MA, Winzelberg A, Golant M et al. Online support groups for Parkinson's patients: a pilot study of effectiveness. Soc Work Health Care 2006;42:23–38. 10.1300/J010v42n02_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barg FK, Gullatte MM. Cancer support groups: meeting the needs of African Americans with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2001;17:171–8. 10.1053/sonu.2001.25946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison KP, Pennebaker JW, Dickerson SS. Who talks? The social psychology of illness support groups. Am Psychol 2000;55:205–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ussher J, Kristen L, Butow P et al. What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:2565–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Docherty A. Experience, functions and benefits of a cancer support group. Patient Educ Couns 2004;55:87–93. 10.1016/j.pec.2003.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaskowich KM, Stam HJ. Cancer narratives and the cancer support group. J Health Psychol 2003;8:720–37. 10.1177/13591053030086006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray RE, Fitch M. Cancer self-help groups are here to stay: issues and challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Care 2001;17:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwakkenbos L, Jewett LR, Baron M et al. The Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network (SPIN): protocol for a cohort multiple randomised controlled trial (cmRCT) design to support trials of psychosocial and rehabilitation interventions in a rare disease context. BMJ Open 2013;3:eoo3563 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reimann A, Bend J, Dembski B. [Patient-centred care in rare diseases: a patient organisations’ perspective]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:1484–93. 10.1007/s00103-007-0382-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zordan RD, Juraskova I, Butow PN et al. Exploring the impact of training on the experience of Australian support group leaders: current practices and implications for research. Health Expect 2010;13:427–40. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00592.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butow P, Ussher J, Kirsten L et al. Sustaining leaders of cancer support groups: the role, needs, and difficulties of leaders. Soc Work Health Care 2005;42:39–55. 10.1300/J010v42n02_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakkalbasi N, Bauer K, Glover J et al. Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. Biomed Digit Libr 2006;3:7 10.1186/1742-5581-3-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.1.0). Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zordan R, Butow P, Batterby E et al. Supporting the supporters: a randomised trial of interventions to assist cancer support group leaders [abstract]. Psychooncology 2009;18(Suppl 2): S31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zordan R, Butow P, Kirsten L et al. Supporting the supporters: a randomised controlled trial of interventions to aid cancer support group leaders [abstract]. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2009;5(Suppl 2):A147 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2009.01233.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zordan R, Butow P, Kirsten L et al. Supporting the supporters: a randomized controlled trial of interventions to assist the leaders of cancer support groups. J Community Psychol 2015;43:261–77. 10.1002/jcop.21677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price M, Butow P, Kirsten L. Support and training needs of cancer support group leaders: a review. Psychooncology 2006;15:651–63. 10.1002/pon.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zordan RD, Butow PN, Kirsten L et al. The development of novel interventions to assist the leaders of cancer support groups. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:445–54. 10.1007/s00520-010-1072-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpenter SK, Cepeda NJ, Rohrer D et al. Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educ Psychol Rev 2012;24:369–78. 10.1007/s10648-012-9205-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodridge D, Hutchinson S, Wilson D et al. Living in a rural area with advanced chronic respiratory illness: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir 2011;20:54–8. 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delisle VC, Gumuchian ST, Pelaez S et al. and the Scleroderma Support Group Project Advisory Team. Reasons for non-participation in scleroderma support groups. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34(Suppl 100(5)):56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013325supp.pdf (89KB, pdf)