Abstract

Objectives

Many reports exist of the cardiovascular toxicity of smoked cannabis but none of arterial stiffness measures or vascular age (VA). In view of its diverse toxicology, the possibility that cannabis-exposed patients may be ageing more quickly requires investigation.

Design

Cross-sectional and longitudinal, observational. Prospective.

Setting

Single primary care addiction clinic in Brisbane, Australia.

Participants

11 cannabis-only smokers, 504 tobacco-only smokers, 114 tobacco and cannabis smokers and 534 non-smokers. Exclusions: known cardiovascular disease or therapy or acute exposure to alcohol, amphetamine, heroin or methadone.

Intervention

Radial arterial pulse wave tonometry (AtCor, SphygmoCor, Sydney) performed opportunistically and sequentially on patients between 2006 and 2011.

Main outcome measure

Algorithmically calculated VA. Secondary outcomes: other central haemodynamic variables.

Results

Differences between group chronological ages (CA, 30.47±0.48 to 40.36±2.44, mean±SEM) were controlled with linear regression. Between-group sex differences were controlled by single-sex analysis. Mean cannabis exposure among patients was 37.67±7.16 g-years. In regression models controlling for CA, Body Mass Index (BMI), time and inhalant group, the effect of cannabis use on VA was significant in males (p=0.0156) and females (p=0.0084). The effect size in males was 11.84%. A dose–response relationship was demonstrated with lifetime exposure (p<0.002) additional to that of tobacco and opioids. In both sexes, the effect of cannabis was robust to adjustment and was unrelated to its acute effects. Significant power interactions between cannabis exposure and the square and cube of CA were demonstrated (from p<0.002).

Conclusions

Cannabis is an interactive cardiovascular risk factor (additional to tobacco and opioids), shows a prominent dose–response effect and is robust to adjustment. Cannabis use is associated with an acceleration of the cardiovascular age, which is a powerful surrogate for the organismal–biological age. This likely underlies and bi-directionally interacts with its diverse toxicological profile and is of considerable public health and regulatory importance.

Keywords: Biological age, Cannabis and aging, Accelerated aging, Biomarkers of aging

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study strengths include its design features including combined cross-sectional and longitudinal structure, the detailed annotation of the database including consideration of multiple clinical, pathological and cardiovascular variables incorporating information on time from exposure to consider exclude cannabinoid effects.

Advanced conceptual understanding and statistical modelling employed.

Significant cannabis exposure in contrast to many previously published studies.

Study limitations included that only 11 cannabis-only patients could be identified of the 125 cannabis-exposed patients.

Significant coefficient of variation was found with the biomarker of cardiovascular–organismal age employed; use of an alternative parameter such as epigenetic age based on DNA methylation would allow more refined and detailed studies in smaller patient groups.

Introduction

With increasing availability of cannabis derivatives in many parts of North America, and intensifying research on the physiology and pharmacology of the endocannabinoid system, cannabinoids are becoming increasingly prominent on the public and research agenda. The Global Burden of Disease project identified that cannabis abuse had a global prevalence of 13 625 000 and was associated with 396 000 years of life lived with disability (YLD), a figure which has increased by 22% from 1990 to 2013.1 Moreover, as substance abuse and mental illness were some of the five major causes of increasing YLD globally1 and with the role of cannabis now established as a gateway drug to various drug dependency syndromes2–5 with several serious psychological disorders,2–5 it is likely that its impact on the global YLD may be larger than is usually measured.

While cannabinoid toxicology is well established in the respiratory and neurological–psychiatric literature, it is less well known that a variety of fascinating studies also exist which portray its effects on the cardiovascular system. The effects of cannabinoids on the cardiovascular system are currently believed to be mediated by several signalling systems and intracellular transduction pathways. These include the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R), cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CBR2), vanilloid, prostanoid, lysophospholipid and unidentified endocannabinoid pathways, among others,6 which interact in complex ways with immune active cells and cytokines,7–9 all of which are subject to increasingly complex levels of epigenetic regulation.10 Case reports exist of serious adverse effects including supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, coronary thrombosis, sudden cardiac death, asystole, angina, epicardial coronary spasm and microvascular mediated no-flow phenomena frequently in very young patients or patients without other cardiovascular risk factors which have been recently collated.11 12 A threefold to fivefold elevation of all causes and cardiac death has been shown within 1 hour of cannabis use in cross-sectional13 and longitudinal studies.14 A large longitudinal study of 1913 individuals showed a dose–response relationship between cannabis exposure and cardiovascular mortality.14 Both acute strokes and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome have been reported in a number of case reports particularly from France, with the mean age of the patients much younger than usual at 32–33 years of age.12 Moreover the very complexity of endocannabinoid vascular physiology implies that it is both nuanced and interactive as CB1- mediated effects are often pro- and CB2- effects anti -vasculitic and -arteriopathic.15 16 Cannabis is now believed to contain 104 cannabinoid compounds.12 As cannabis use becomes more widespread a more complete appreciation of its clinical presentations becomes an increasing imperative.

Implicit within its diverse multi-system toxicological profile, which also includes an association with cancers of several sites,4 17–19 is the distinct possibility that it may be altering the underlying rate of ageing of the whole organism. Immune modulation–oxidative stress20 and epigenetic change21 are believed to be major drivers of the ageing process, and cannabinoids are now known to be involved in both.22 Cannabinoids have also been linked with stem cell physiology23 24 as well as increased mitochondrial uncoupling and oxyradical flux.25 26 Moreover, it is established in cardiovascular medicine that since the majority of deaths in western nations are due to cardiovascular causes, one’s cardiovascular age is a powerful surrogate for organismal or biological age.27 28 Many stem cell niches have a vascular component.29 30 It follows therefore that if one could measure cardiovascular age, a surrogate for organismal age could be established and one could test the hypothetical link between cannabis use and the ageing process.

Indeed, just such an opportunity was afforded recently in our clinic with the secondary analysis of a longitudinal cardiovascular database. Encoded cannabis use details in text format were available. The AtCor SphygmoCor system measures arterial stiffness and links it algorithmically to vascular–biological age. As we see both general and drug-addicted patients and as cannabis use is common among the latter group, it was decided to undertake the present analysis.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients were not selected. Patients presenting to the clinic were studied in consecutive order in accordance with the dictates of workflow on the day of presentation. Patients were restudied, again opportunistically, on presentation to the clinic at approximately the 2-year and 5-year marks. Opioid-dependent patients were prescribed buprenorphine both at presentation and throughout their care.

Our clinic sees 250–350 patients weekly. We have worked in addiction medicine since 1998. We have seen more than 2699 of the ∼5500 known registered opioid-dependent patients in Queensland.

Radial arterial pulse wave tonometry (RAPWT)

Radial arterial pulse wave tonometry (RAPWT) was performed with the Atcor SphygmoCor (Sydney, Australia) system V.7.0 as previously described.31 Patients were positioned supine on a bed and the radial arterial pulse wave was sampled using a probe containing a Millar micromanometer sensor. Input biophysical data were analysed by the SphygmoCor software. Accepted studies were required to have an Operator Index >70% and to be technically satisfactory. All studies were performed in quintuplicate. The central waveform was standardised against the brachial blood pressure obtained sphygmanometrically using an Omron HEM-907 automated blood pressure device (Tokyo, Japan). Many indices were collected from this system including central and peripheral pressure augmentation, timing indices and pressure indices. The vascular and reference ages (VA, RA) were calculated internally by the software from an algorithm matching the degree of arterial stiffening with height, age and sex. Patients were allowed to eat, drink and smoke prior to study.

Demographic and laboratory data

At the time RAPWT was performed, patients were asked about drug use and the duration for which these drugs had been used. Patients usually quantified cannabis use as cones/day, which equates to ∼0.1 g/day. They were also asked when they had last used drugs, including tobacco, as this can affect the RAPWT result. This information was entered as notes into a RAPWT database. The RAPWT data were linked with our clinical pathology database. Clinical pathology testing of our patients was performed by Queensland Medical Laboratories, which are accredited to both the Australian Standard AS-15189 and the International Laboratory Standard ISO- 9001. Data are listed as mean±SEM. Blood was drawn at initial presentation and as clinically indicated thereafter and also on an approximately annual basis to update their clinical profiles. Laboratory data from the time of their RAPWT was combined with the clinical and RAPWT data for analysis.

Statistics

Data were held in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Redmond, Washington, USA). All data shown are listed as mean (±SEM). Categorical data were compared using EpiInfo 7.1.4.0 from Centres for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Bivariate analysis was conducted using Statistica V.7.1 (Statsoft Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA). All t-tests were two-tailed. Linear regression was performed in ‘R’ V.3.2.3 from the Cloud Central R Archive Network (CRAN) mirror using the base, reshape, ggplot2, and nlme packages. In order to comply with normality assumptions, continuous variables were log transformed as indicated by the Shapiro test. Time-dependent analyses were conducted using repeated measures non-linear mixed effects restricted maximum likelihood estimator (REML) models with unity and the patient’s unique identifier as random effects. Models were fitted as suggested by loess plots and quantitated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) models. Repeated measures models were compared by maximum likelihood (ML) methods. Model reduction was conducted classically, with the progressive elimination of the least significant term. Missing data were casewise deleted. To calculate effect sizes, mean dependent variable parameters (age, BMI and time) were used together with the coefficient estimates obtained from the final regression models. Standard abbreviations relating to statistical models such as degrees of freedom (DF), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Log-likelihood ratio (Log.Lik) are used. p<0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics

All patients gave informed consent to the performance of the RAPWT and the inclusion of their anonymised data in the present analysis. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of South City Medical Centre, which is registered with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The study was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

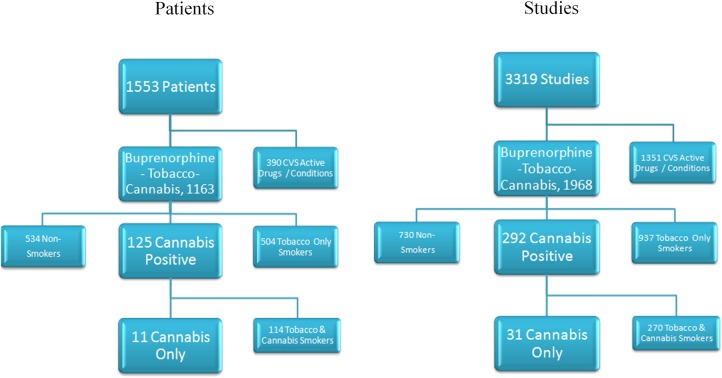

Data from 13 657 RAPWT studies were collected from 1553 patients. Three hundred and ninety cases were excluded because of exposure to conditions (hypertension, drug withdrawal) or medications (amphetamine, alcohol, heroin), which were known to interfere with central cardiovascular status. Cocaine use was not reported by our patients. Cocaine use in Australia is very uncommon outside of Sydney and outside of certain sociodemographically restricted subgroups. Methadone has also been shown by our group to perturb cardiovascular status32 and was therefore also excluded. This left 1163 patients including 817 (70.25%) males. The breakdown by study group is shown in figure 1, and by age, group and sex in table 1. The 1163 patients included in this study were studied by RAPWT on 1968 occasions. Patients were categorised by their inhalant use as being complete non-smokers, smokers of tobacco only, smokers of cannabis only, or smokers of both. As shown, only 11/125 (8.80%) tobacco and/or cannabis smokers smoked cannabis only, and only 31/292 (10.62%) studies of cannabis and/or tobacco smokers were performed (recurrently) on cannabis-only subjects.

Figure 1.

Outline of overall study numbers and groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, drug use and cardiovascular data

| THC-None | THC-Tob | THC-Both | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | None (534) | Tobacco (504) | THC (11) | Both (114) | p Value | p Value | p Value |

| Chronological age (years) | 30.47 (0.48) | 33.33 (0.40) | 40.36 (2.44) | 34.56 (0.88) | 0.0032 | 0.0100 | 0.0491 |

| No. In longitudinal series | 730 | 937 | 31 | 270 | |||

| Male, N (%) | 371 (69.5%) | 356 (70.6%) | 10 (90.9%) | 80 (70.2%) | 0.2293 | 0.2610 | 0.2536 |

| Height (cm) | 173.64 (0.38) | 173.65 (0.37) | 180 (1.83) | 173.71 (0.95) | 0.0172 | 0.0132 | 0.0077 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.61 (0.65) | 74.63 (0.67) | 80.73 (5.28) | 70.39 (1.28) | 0.1211 | 0.1887 | 0.0204 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m−2) | 24.35 (0.18) | 24.66 (0.19) | 24.84 (1.48) | 23.22 (0.32) | 0.7043 | 0.8921 | 0.1505 |

| Drug use | |||||||

| Tobacco | |||||||

| Cigarettes/day | 0.2 (0.1) | 17.27 (0.42) | 0 (0) | 19.95 (0.92) | 0.7869 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Years of tobacco | 14 () | 21.37 (2.17) | – | 23.6 (4.99) | |||

| Packet-years tobacco | 0 () | 19.74 (1.75) | – | 19.1 (3.55) | |||

| Minutes after tobacco | 30 (9.87) | 115.61 (15.37) | 90 () | 95.71 (29.74) | 0.0682 | 0.9244 | 0.9828 |

| Opioids | |||||||

| Buprenorphine dose (mg) | 7.44 (0.97) | 6.49 (0.24) | 5.05 (1.20) | 7.25 (0.60) | 0.4876 | 0.5501 | 0.4338 |

| Dosing buprenorphine, N (%) | 52 (9.7%) | 402 (79.7%) | 4 (36.4%) | 83 (72.8%) | 0.0174 | 0.0019 | 0.0302 |

| Heroin dose (g) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.43 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.11) | 0.37 (0.03) | 0.1287 | 0.2178 | 0.3143 |

| Heroin duration (years) | 1.84 (0.31) | 11.02 (0.41) | 6.8 (3.05) | 11.11 (0.85) | 0.1398 | 0.1265 | 0.1350 |

| Heroin exposure (g-years) | 0.93 (0.2) | 5.47 (0.35) | 4.65 (2.53) | 5.13 (0.59) | 0.1772 | 0.7258 | 0.8120 |

| Cannabis | |||||||

| Cannabis use (g/d, cones=0.1 g/d) | 0 (0) | 0.06 (0.04) | 17.45 (5.65) | 10.5 (1.32) | 0.0115 | 0.0117 | 0.1290 |

| Cannabis duration (years) | () | 28.5 (8.5) | 8.5 (3.5) | 18.94 (2.65) | 0.1616 | 0.2191 | |

| Cannabis exposure (g-years) | – | – | 17.5 (12.5) | 38.88 (8.27) | 0.4259 | 0.4147 | |

| Time after cannabis (min.) | – | 60 (45.17) | 952.5 (320.4) | 842.34 (81.11) | 0.0672 | 0.7081 | |

| Cardiovascular parameters | |||||||

| Central augmentation | |||||||

| Vascular age | 32.87 (0.69) | 36.22 (0.77) | 56.91 (7.86) | 39.65 (1.63) | 0.0121 | 0.0253 | 0.0550 |

| Vascular age/chronological age | 1.09 (0.02) | 1.09 (0.02) | 1.4 (0.19) | 1.15 (0.04) | 0.1488 | 0.1393 | 0.2312 |

| Log (vascular age/chronological age) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.1 (0.06) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.0410 | 0.0408 | 0.1452 |

| Vascular age—chronological age | 2.35 (0.53) | 2.87 (0.63) | 16.46 (6.75) | 5.06 (1.26) | 0.0635 | 0.0722 | 0.1259 |

| Central augmentation index (C_AI) | 111.39 (0.84) | 113.88 (0.8) | 133.27 (7.16) | 118.98 (1.77) | 0.0002 | 0.0005 | 0.0200 |

| Central augmentation pressure at HR=75 (C_AP) | 2.05 (0.22) | 3.02 (0.21) | 7.27 (1.8) | 4.02 (0.44) | 0.0007 | 0.0040 | 0.0329 |

| Central augmented press./pulse Ht. Ratio at HR=75 (C_AGPH_HR75) | 5.37 (0.57) | 7.86 (0.56) | 17.73 (3.99) | 10.88 (1.12) | 0.0021 | 0.0101 | 0.0725 |

| Central pulse height (C_PH) | 35.15 (0.31) | 36.29 (0.31) | 40.36 (2.32) | 38.09 (0.65) | 0.0177 | 0.0569 | 0.3014 |

| Central augmentation load (C_AL) | 8.27 (0.24) | 8.59 (0.22) | 12.55 (1.74) | 9.04 (0.42) | 0.0042 | 0.0041 | 0.0144 |

| Pulse pressure amplification ratio (PPAmpRatio) | 156.82 (0.83) | 154.06 (0.84) | 135.55 (4.88) | 148.63 (1.78) | 0.0003 | 0.0013 | 0.0280 |

Data are listed as mean (±SEM).

THC is an abbreviation for tetrahydrocannabinol, the major psychoactive cannabinoid present in cannabis plants.

The three columns on the extreme right of this table list the p values for the two-way, two-tailed comparison of the groups specified in the column headings. The statistical test used was Student's t-test. HR, heart rate.

Detailed comparative drug use and demographic data are given in table 1, along with selected bivariate group comparisons. Table 1 also shows that the proportion of patients in each group dosing on buprenorphine was different. For the purposes of this analysis, these differences were disregarded as there are few reports of the cardiovascular toxicity of buprenorphine, the dose was lowest in the cannabis group and therefore in the reverse direction from the effects herein described, the mean buprenorphine dose in the cannabis-only group was only 5.05±1.2 mg which is very low, and the previously reported effect is of low magnitude.32 This issue is considered in detail in an accompanying Statistical Appendix including online supplementary figures S1–S4 and tables S1–S5. Bivariate comparisons showed significant differences in several augmentation indices. Comparative clinical laboratory data from the time of patients' initial presentation is shown in online supplementary table S6. Further detailed cardiovascular data are shown in online supplementary table S7.

bmjopen-2016-011891supp.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

It is important to note that the mean cannabis use in the groups exposed to cannabis was much higher than that seen in many reports from developed nations (table 1). The overall cannabis use was 37.67±7.16 g-years (mean±SEM) and median 32.5 (range 1–135), which is much higher than seen by other widely quoted authors.33

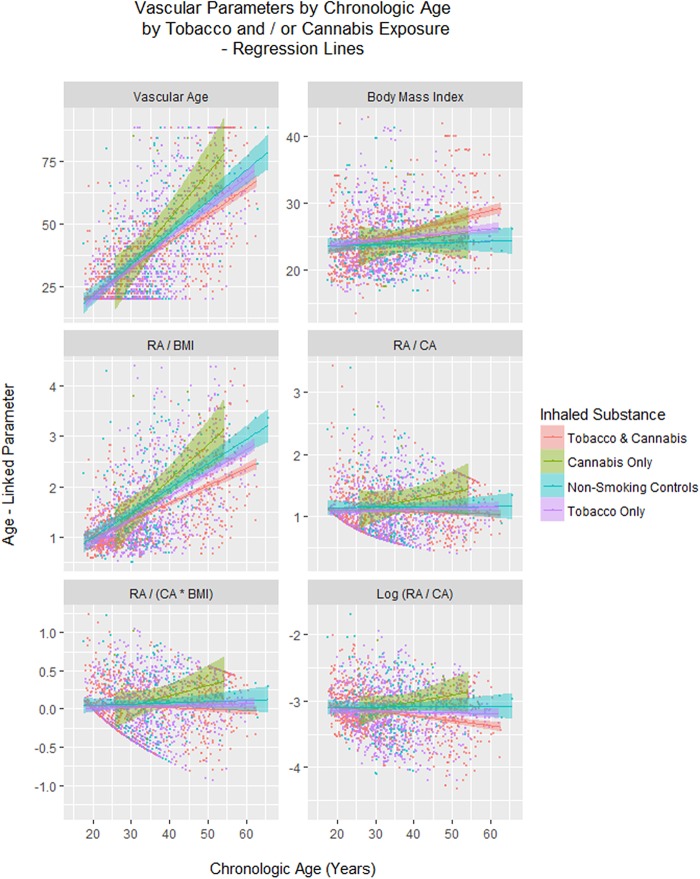

Figure 2 shows various cardiovascular age-related parameters as a function of chronological age (CA), and similar indices are shown as a function of time in online supplementary figure S5. Online supplementary figures S6 and S7 show similar data with loess curves fitted.

Figure 2.

Vascular age parameters by chronological age and drug exposure type. BMI, Body Mass Index; CA, chronological age; RA, reference or vascular age.

As indicated in tables 1 and 2, online supplementary figures S5–S9 and as previously noted in earlier reports,34 BMI is a particularly important variable to control for in these analyses as it follows different time courses between groups. In a mixed-effects model regressing BMI against CA, time and inhalant group, the age–cannabis interaction was significant (est.=−0.0108, DF=736, t=−2.0668, p=0.0391) and the age–cannabis-and-tobacco group bordered on significance (est.=−0.0066, DF=736, t=−1.8923, p=0.0588; model AIC=−3366.4, BIC=−3327.3, Log.Lik=1690.2).

Table 2.

Multiple regression

| Cross-sectional models—linear regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Parameter values |

Model values |

||||||

| Estimate | Std. Error | t | p Value | Adj. R Squ. | F | DF | p value | |

| Males, cross-sectional | ||||||||

| Age: systolic pressure | 0.1744 | 0.0242 | 7.218 | 0.0000 | 0.3755 | 23.84 | 4, 148 | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic pressure | 0.8248 | 0.2696 | 3.060 | 0.0026 | ||||

| Age: BMI: cannabis use | 0.0061 | 0.0024 | 2.523 | 0.0127 | ||||

| Systolic pressure | −0.9205 | 0.3919 | −2.349 | 0.0202 | ||||

| Females, cross-sectional | ||||||||

| Age: systolic pressure | 0.1744 | 0.0242 | 7.218 | 0.0000 | 0.3755 | 23.84 | 4, 148 | <0.0001 |

| BMI: systolic pressure | 0.4896 | 0.1519 | 3.223 | 0.0026 | 0.3838 | 7.697 | 4, 39 | 0.0001 |

| BMI | −2.4585 | 0.7665 | −3.207 | 0.0027 | ||||

| Cannabis use | 5.626 | 1.8139 | 3.102 | 0.0036 | ||||

| Cannabis use: systolic pressure | −1.118 | 0.3744 | −2.986 | 0.0049 | ||||

| Longitudinal model—mixed effects repeated measures model | ||||||||

| Parameter | Parameter values |

Model values |

||||||

| Statistical measure | Value | Std. Error | DF | t-value | p Value | AIC | BIC | Log.Lik |

| Age: systolic pressure | 0.2153 | 0.0193 | 146 | 11.1602 | <0.0001 | 401.1985 | 464.4476 | −185.5992 |

| Age: tobacco use: systolic pressure | 0.1574 | 0.0483 | 146 | 3.2554 | 0.0014 | |||

| Tobacco use: systolic pressure | −0.5651 | 0.1750 | 146 | −3.2300 | 0.0015 | |||

| Age: BMI: tobacco use: systolic pressure | −0.0170 | 0.0060 | 146 | −2.8099 | 0.0056 | |||

| BMI: tobacco use: systolic pressure | 0.0587 | 0.0214 | 146 | 2.7439 | 0.0068 | |||

| Tobacco use | 1.8059 | 0.6619 | 146 | 2.7284 | 0.0071 | |||

| Age: tobacco use | −0.4930 | 0.1831 | 146 | −2.6925 | 0.0079 | |||

| Cannabis use: tobacco use | 0.6505 | 0.2420 | 146 | 2.6883 | 0.0080 | |||

| Age: cannabis use: tobacco use | −0.1844 | 0.0692 | 146 | −2.6643 | 0.0086 | |||

| BMI: cannabis use: tobacco use | −0.1956 | 0.0757 | 146 | −2.5843 | 0.0107 | |||

| Age: BMI: cannabis use: Tobacco use | 0.0556 | 0.0217 | 146 | 2.5661 | 0.0113 | |||

| Diastolic pressure | 0.2866 | 0.1250 | 146 | 2.2933 | 0.0233 | |||

AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; BMI, Body Mass Index; DF, degrees of freedom.

The relationship between the (log) vascular age (VA) and the (log) CA, (log) BMI, time and inhalant group was best described in males by a cubic mixed-effects model (linear maximum likelihood final model, AIC=715.32, DF=19, cubic final model AIC=713.67, DF=28, Log. Ratio=19.65, p=0.0202) including significant terms for the interaction between the square of CA and cannabis exposure (est.=1.722, DF=470, p=0.0156, respectively; model AIC=819.283, BIC=964.58, Log.Lik=−381.64). Among females, when the VA/CA ratio was regressed against time, (log) BMI and inhalant exposure group, the time–cannabis interaction was significant (est.=−0.0922, DF=241, t=−2.6557, p=0.0084; model AIC=402.25, BIC=433.16, Log.Lik=−194.12).

No acute pressor cardiovascular effects of cannabis exposure were detectable in the data set in this study as suggested by online supplementary figure S10; which may be interpreted as mainly showing the predominance of the vasodilatory effect of cannabinoids in the medium-term postexposure period (analysis not presented).

Gender was also found to be significant factor (see online supplementary figures S11 and S12). When the VA/CA ratio was regressed against CA, time, BMI and sex, the BMI–time–male sex and time–male sex interactions were significant (est.=−0.0.0657 and −0.02147, DF=724, t=2.636 and −2.620, p=0.0086 and 0.0090; model AIC=1209.83, BIC=1315.78, Log.Lik=−585.91). However, as there was only a single female patient in the cannabis-only group, this measure cannot be regarded as robust. This female had five measurements taken on her over time, but died at the age of 35 years from breast cancer.

As figures 1 and online supplementary figure S5 suggest that cannabis-exposed patients may be ageing faster than other groups, it was of interest to quantify these effects. Among males, the VA/CA ratio was regressed against CA, time, BMI and inhalant group. A final mixed-effects model was obtained (AIC=821.715, BIC=920.438, Log.Lik=−391.857) which indicated an 11.84% advance of the VA over CA at a mean age of 34.85 years, thus indicating a 4.12-year gain to 38.98 years. This exercise was not possible in females as the model failed to converge. However, a simpler mixed-effects model, based on online supplementary figure S12 regressed the VA/CA ratio against age and inhalant group (AIC=392.699, BIC=436.818, Log.Lik=−186.349). Insertion of coefficients into this model indicated that at age 45, females had an 8.35% increase of VA over CA, a 3.75-year advance.

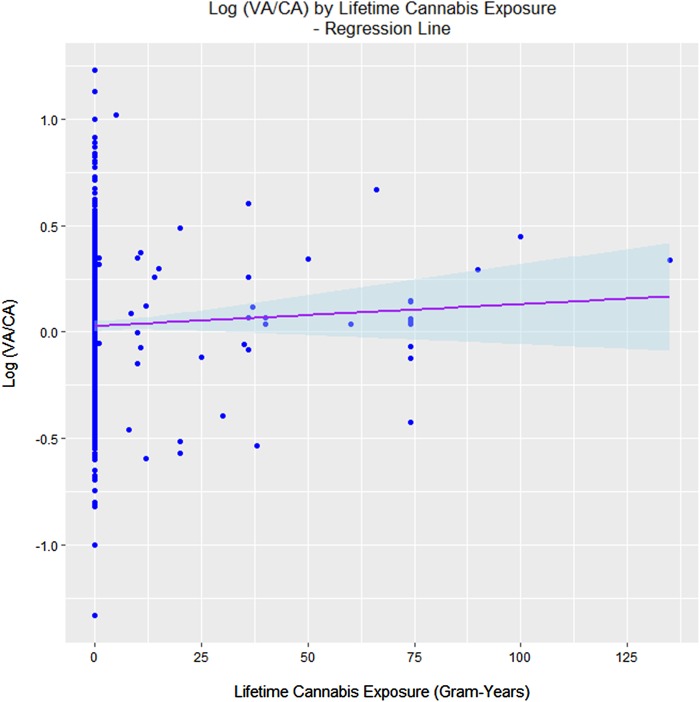

The next question relates to a possible dose-duration effect with lifetime cannabis exposure. Figure 3 shows the dose–response effect when the log (VA/CA) ratio is plotted against lifetime cannabis exposure. In a linear regression model of VA against CA and lifetime cannabis exposure, the exposure is significant (est.=−0.9188, T=−3.645, p=0.0017) and the CA–cannabis exposure is also significant (est.=0.2451, t=4.091, p=0.0006; model Adj. R Squ.=0.4239, F=8.727, DF=2, 19, p=0.0020). When VA is regressed against CA and dose and duration considered separately in a mixed-effects model, the cannabis duration is significant (est.=−2.057, DF=21, t=−4.896, p=0.0001) and the CA–cannabis duration interaction is significant (est.=0.4563, DF=17, t=5.824, p<0.0001; model AIC=37.129, BIC=45.317, Log.Lik.=−13.565).

Figure 3.

Dose–response effect of the vascular age/chronological age (VA/CA) ratio.

An important issue in cannabis toxicity is its quantitative relationship to tobacco toxicity. It was not clear whether it would be possible to demonstrate a difference with our limited numbers of cannabis-only-exposed patients. This question was addressed by assigning the tobacco-only group as the comparator group when regressing the VA against CA and the inhalant group. In a mixed-effects model cubic in CA (better than linear, ANOVA test: AIC=1090.08 and 1064.32, DF=18 and 10, L.Ratio=41.762, p<0.0001), the CA–cannabis interaction, cannabis exposure, and the square of CA and cannabis interaction were significant (est.=−2.989, 5.878, −11.282, DF all=725, t=−2.766, 2.51 and −2.289, p=0.0058, 0.01120 and 0.0223; model AIC=1101.7, BIC=1202.08 and Log.Lik.=−532.85).

Similarly, our group has previously shown that opioid exposure was linked with accelerated cardiovascular ageing in both cross-sectional31 32 35 36 and longitudinal studies.31 32 34 37 It was thus of interest to determine if the apparent cardiovascular effect of cannabis could be quantitatively differentiated from that of opioids. As noted, patients currently on methadone were excluded from the present analysis. When the (log) VA/CA ratio was regressed against terms for both cannabis and opioid dose and duration of exposure, terms for cannabis duration and use level remained significant from p=0.0051 and p=0.0100, respectively (see online supplementary table S8 for details).

Finally, it was of interest to consider if the effect of cannabis was independent of, or possibly additive to other known cardiovascular risk factors. In males, the log VA was regressed against interactive terms in CA, BMI, cannabis and tobacco use, and also additive terms (to limit the number of potential interactions) in brachial systolic pressure, cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL), Low density lipoprotein (LDL), pulse rate and high sensitivity C reactive protein. In exploratory analyses, inclusion of the time since cannabis and tobacco consumption was not significant, so these terms were omitted from the regression models. As shown in table 2, the interaction between CA, BMI and cannabis use was significant (p=0.0127). In females with a smaller data set, the log RA/CA ratio was regressed against the same group of independent variables. Again cannabis use remained significant from p=0.0036 (details in table 2). Owing to technical difficulties with the female sample, both sexes were analysed together in the longitudinal study by mixed-effects modelling using a model similar to that described above for males. Cannabis terms were significant from p=0.0080 (table 2).

Discussion

The results demonstrate for the first time that patients exposed to cannabis demonstrate an advanced cardiovascular age in a longitudinal time series. This cross-sectional and longitudinal study of 1163 patients excluded patients known to be affected by cardiovascular disease or medication. The level of cannabis exposure in our group was much higher than that commonly reported in developed nations which is an important methodological issue, particularly in the context of more widespread use of more potent formulations.2 4 5 The results demonstrate for the first time that patients exposed to cannabis demonstrate an advanced cardiovascular age in a longitudinal clinical series. The effect size in males was quantified as 11.84% at the mean CA. A dose–response effect was demonstrated (p=0.0017, 0.0001 and <0.0001). When directly tested against tobacco there was an additional effect of lifetime cannabis exposure (from p=0.0058). Similarly, when compared with opioid dependence from which methadone had been excluded, cannabis use remained significant (from p=0.0051). Statistical adjustment for the acute effects of cannabis and tobacco did not account for these findings. When tested in multivariate mixed-effects models, terms for cannabis exposure remained significant in interaction with known cardiovascular risk factors after adjustment. Moreover, the effect of cannabis was shown to be related by power functions to the square and cube of the CA (BMI and tobacco analyses and online supplementary tables S1 and S3) suggesting that these effects became much more marked with advancing age.

While these findings relate primarily to the cardiovascular system (CVS), the centrality of the CVS to the ageing process, at both the macrovascular and microvascular and particularly stem cell niche levels, implies that the findings may be generalised across the organism and demonstrate an organism-wide acceleration of the ageing process. The implication of the study is that the diverse and varied toxicological profile of cannabis dependence—and even occasional use—is not happening randomly or in separate systems isolated from each other but may be linked to a coordinated degenerative organism-wide process, which often appears clinically as an advanced ageing process, and has now been quantified to indeed be so. This study is strictly observational and is not designed mechanistically. However, the conceptual perspective from which the study was conceived is uniquely from ageing medicine. This the first time cannabis dependence has been considered as a disorder of ageing, and it brings to the varied field of the toxicology of cannabis new and conceptually unifying insights from ageing medicine whereby previously reported disparate findings of immune modulation,8 9 38 impaired mitochondrial function,25 39 epigenetic change and drift,10 40 microvascular30 and immune mediated41 effects on stem cell niches, and hypothalamic-limbic system dysfunction42 43 can be brought into coherent and meaningful conceptual focus.

Some consideration of the cardiovascular physiology of cannabinoids is also of interest. A diverse array of receptor subtypes, ion channels, intracellular transduction signalling cascades and epigenetic mechanisms has been implicated in the cardiovascular effects of various cannabinoids. Receptors which have been implicated largely in animal studies include CB1, eCB,44 cholinergic muscarinic,6 45 46 vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1)/transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) (and other TRPV channels).47–49 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR’s)6 G-protein receptor 18 (GPR18)50 and G-protein receptor 55 (GPR55) and serotonin 1a receptor (5HT1A) channels have also been implicated in some studies.6 CB2, Prostanoid (thromboxane receptor (TP), prostacyclin receptor (IP), prostaglandin E2 receptor encoded by human PTGER1 (EP1) and prostaglandin E2 receptor encoded by human PTGER4 (EP4)) channels and the calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) receptor are also indirectly involved.6 Ionic channels implicated include calcium activated potassium channels of various sizes50–54 and calcium channel inhibition.47 48 Several signalling cascades have been implicated including Akt (protein kinase B),47 48 protein kinase C,48 ceramide, lysophospholipids,47 48 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK’s) extracellular related kinase (ERK), p38 and c-Jun kinases,47–49 nitric oxide,53 55 and GPR556 via endothelium-dependent mechanisms and endothelium-independent mechanisms. Epigenetic mechanisms induced by miRNA-655 and others have also been implicated.10 Cannabinoid-induced epigenetic effects have also been shown to act transgenerationally.56 57 Interestingly, cannabinoids have been shown on occasion to act biphasically on CVS with initial pressor and tachycardic effects, and decreased cardiac perfusion, followed by depressor hypotensive and bradycardic periods, mediated alternately by vanilloid and CB1 receptors,58 59 or sympathetic–parasympathetic-vagal fluctuations, respectively.46 Clearly, these effects would account for the increased clinical presentations after acute exposure. It is likely that with chronic use habituation develops to some degree to many of these cardiovascular effects.60 61

The study has several strengths including its dually cross-sectional and longitudinal design, the use of advanced statistical methods and modelling, the use of an advanced systems for cardiovascular monitoring, the coordination of clinical and laboratory data, and its wide ranging conceptual framework. Importantly, the level of cannabis exposure in our group was significant, so that the chance of a false negative finding from inadequate exposure among the study population, as has been seen elsewhere,19 is correspondingly reduced. The weaknesses in the study relate to the reliance on patient recall and history for drug use data, which opens the study to uncontrolled confounding. There are also only a small number of cannabis-only patients. Of 125 patients reporting cannabis use, only 11 claimed to use cannabis exclusively. This is likely to be a common limitation of many clinic-based studies where drug use is not tightly controlled. Contrariwise, its real world location in a primary care clinic makes the findings more likely to be generalisable. The potential generalisability of our study would relate mainly to the amounts of cannabis consumed. As noted, while the amounts of cannabis to which our subjects were exposed was greater than that described in published reports from earlier decades,2 5 19 33 it seems clear that the amount of cannabis consumed in many places is rising related to its increasing availability and increasing potency5 12 combined with the popular misunderstanding relating to its supposed relative safety and benignity as an addictive substance.5 12 Most of our cannabis-exposed patients were also prescribed low dose buprenorphine (mean of 5 mg), but this has been shown to likely have a negligible effect on the results reported. The use of drug testing and a formal instrument for cannabis exposure would be improvements, which could be employed in future iterations or replications of the study. Many other methods of determining biological age have since been described and are applicable to the problems of addiction medicine. The epigenetic method discovered by Horvath,21 and reported to be robust across many cell types and disorders, is of particular interest as it has an unusually low variance which would allow the sensitive determination of small effects from relatively limited sample sizes.

Overall, this study raises important issues for public concern and further research. It is clear from these data that cannabis use is associated with an acceleration of the ageing process as measured by its surrogate cardiovascular age based on arterial stiffness and the known relationship of vascular health to general mortality and the centrality of microvascular integrity to the health and maintenance of many stem cell niches. The present work raises the real concern that diverse reports of cannabis-related harms are in fact related not just to organ-specific disorders and free radical flux,19 33 but to an overall acceleration of the ageing process in these patients which may be expected to become more clinically prominent as cannabis use becomes more widespread, apparently driven in no small part by commercial interests. As such, the findings reported in this study should be of concern to public health authorities and policymakers alike, and indeed to the wider community. There are many ways to extend these findings including by studies of circulating stem cells and epigenetic age, and such refinements and increasingly sophisticated investigations of these questions is amply justified in view of the rapidly gathering public health situation, which is clearly building internationally.

Footnotes

Contributors: ASR designed the study, treated the patients, conducted the PWA studies, analysed the data and wrote the initial draft of the paper. GKH gave advice on study design and data analysis, wrote the paper and assisted with literature review. AN assisted with literature review and wrote the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Southcity Medical Centre Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ et al. , GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015;386:2145–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet 2009;374:1383–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Hayatbakhsh MR et al. Cannabis use and educational achievement: findings from three Australasian cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;110:247–53. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reece AS. Chronic toxicology of cannabis. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:517–24. 10.1080/15563650903074507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM et al. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2219–27. 10.1056/NEJMra1402309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanley C, O'Sullivan SE. Vascular targets for cannabinoids: animal and human studies. Br J Pharmacol 2014;171:1361–78. 10.1111/bph.12560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffens S, Veillard NR, Arnaud C et al. Low dose oral cannabinoid therapy reduces progression of atherosclerosis in mice. Nature 2005;434:782–6. 10.1038/nature03389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein TW, Cabral GA. Cannabinoid-induced immune suppression and modulation of antigen-presenting cells. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2006;1:50–64. 10.1007/s11481-005-9007-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein TW, Newton C, Larsen K et al. The cannabinoid system and immune modulation. J Leukoc Biol 2003;74:486–96. 10.1189/jlb.0303101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Möhnle P, Schütz SV, Schmidt M et al. MicroRNA-665 is involved in the regulation of the expression of the cardioprotective cannabinoid receptor CB2 in patients with severe heart failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;451:516–21. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchetti D, Spagnolo A, De Matteis V et al. Coronary thrombosis and marijuana smoking: a case report and narrative review of the literature. Drug Test Anal 2016;8:56–62. 10.1002/dta.1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Hall W, Renstrom M et al., ed. Cannabis: the health and social effects of non-medical cannabis use. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, United Nations, 2016;5:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M et al. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation 2001;103:2805–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.23.2805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE et al. An exploratory prospective study of marijuana use and mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008;155:465–70. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steffens S, Pacher P. Targeting cannabinoid receptor CB(2) in cardiovascular disorders: promises and controversies. Br J Pharmacol 2012;167:313–23. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02042.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slavic S, Lauer D, Sommerfeld M et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 inhibition improves cardiac function and remodelling after myocardial infarction and in experimental metabolic syndrome. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:811–23. 10.1007/s00109-013-1034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang ZF, Morgenstern H, Spitz MR et al. Marijuana use and increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999;8:1071–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chacko JA, Heiner JG, Siu W et al. Association between marijuana use and transitional cell carcinoma. Urology 2006;67:100–4. 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP et al. Epidemiologic review of marijuana use and cancer risk. Alcohol 2005;35:265–75. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kapser DL et al., eds. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 17th edn 1 New York: McGraw Hill, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 2013;14:R115 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Chromothripsis and epigenomics complete causality criteria for cannabis- and addiction-connected carcinogenicity, congenital toxicity and heritable genotoxicity. Mutat Res 2016;789:15–25. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Ma S, Wang Q et al. Effects of cannabinoid receptor type 2 on endogenous myocardial regeneration by activating cardiac progenitor cells in mouse infarcted heart. Sci China Life Sci 2014;57:201–8. 10.1007/s11427-013-4604-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noonan MA, Eisch AJ. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by cannabinoids. Chem Today 2006;24:84–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarafian TA, Kouyoumjian S, Khoshaghideh F et al. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol disrupts mitochondrial function and cell energetics. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;284:L298–306. 10.1152/ajplung.00157.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolff V, Schlagowski AI, Rouyer O et al. Tetrahydrocannabinol induces brain mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction and increases oxidative stress: a potential mechanism involved in cannabis-related stroke. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:323706 10.1155/2015/323706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakatta EG, Wang M, Najjar SS. Arterial aging and subclinical arterial disease are fundamentally intertwined at macroscopic and molecular levels. Med Clin North Am 2009;93:583–604. Table of Contents 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Couteur DG, Lakatta EG. A vascular theory of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010;65:1025–7. 10.1093/gerona/glq135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafii S, Butler JM, Ding BS. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature 2016;529:316–25. 10.1038/nature17040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okabe K, Kobayashi S, Yamada T et al. Neurons limit angiogenesis by titrating VEGF in retina. Cell 2014;159:584–96. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Impact of lifetime opioid exposure on arterial stiffness and vascular age: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in men and women. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004521 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Impact of opioid pharmacotherapy on arterial stiffness and vascular ageing: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2013;13:254–66. 10.1007/s12012-013-9204-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hashibe M, Morgenstern H, Cui Y et al. Marijuana use and the risk of lung and upper aerodigestive tract cancers: results of a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:1829–34. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Opiate dependence as an independent and interactive risk factor for arterial stiffness and cardiovascular ageing—a longitudinal study in females. J Clin Med Res 2013;5:356–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Lifetime opiate exposure as an independent and interactive cardiovascular risk factor in males: a cross-sectional clinical study. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2013;9:551–9. 10.2147/VHRM.S48030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Opiate exposure increases arterial stiffness, advances vascular age and is an independent cardiovascular risk factor in females: a cross-sectional clinical study. World J Cardiovascular Diseases 2013;3:361–70. 10.4236/wjcd.2013.35056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Duration of opiate exposure as a determinant of arterial stiffness and vascular age in male opiate dependence: a longitudinal study. J Clin Pharm Ther 2013;39:158–67. 10.1111/jcpt.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tashkin DP, Baldwin GC, Sarafian T et al. Respiratory and immunologic consequences of marijuana smoking. J Clin Pharmacol 2002;42(11 Suppl):71S–81S. 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarafian TA, Habib N, Oldham M et al. Inhaled marijuana smoke disrupts mitochondrial energetics in pulmonary epithelial cells in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L1202–9. 10.1152/ajplung.00371.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szutorisz H, DiNieri JA, Sweet E et al. Parental THC exposure leads to compulsive heroin-seeking and altered striatal synaptic plasticity in the subsequent generation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014;39:1315–23. 10.1038/npp.2013.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selleri C, Maciejewski JP, Sato T et al. Interferon-gamma constitutively expressed in the stromal microenvironment of human marrow cultures mediates potent hematopoietic inhibition. Blood 1996;87:4149–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reece AS, Hulse GK. Hypothalamic pathophysiology in the neuroimmune, dysmetabolic and longevity complications of chronic opiate dependency. J Forensic Toxicol Pharmacol 2015;3:3–46. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coller JK, Hutchinson MR. Implications of central immune signaling caused by drugs of abuse: mechanisms, mediators and new therapeutic approaches for prediction and treatment of drug dependence. Pharmacol Ther 2012;134:219–45. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duncan M, Kendall DA, Ralevic V. Characterization of cannabinoid modulation of sensory neurotransmission in the rat isolated mesenteric arterial bed. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004;311:411–19. 10.1124/jpet.104.067587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham JD, Li DM. Cardiovascular and respiratory effects of cannabis in cat and rat. Br J Pharmacol 1973;49:1–10. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1973.tb08262.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niederhoffer N, Szabo B. Effect of the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55212-2 on sympathetic cardiovascular regulation. Br J Pharmacol 1999;126:457–66. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hiley CR, Ford WR. Cannabinoid pharmacology in the cardiovascular system: potential protective mechanisms through lipid signalling. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2004;79:187–205. 10.1017/S1464793103006201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, Gao B, Mirshahi F et al. Functional CB1 cannabinoid receptors in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem J 2000;346:Pt 3:835–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Bátkai S et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptors promote oxidative stress and cell death in murine models of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy and in human cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 2010;85:773–84. 10.1093/cvr/cvp369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacIntyre J, Dong A, Straiker A et al. Cannabinoid and lipid-mediated vasorelaxation in retinal microvasculature. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;735:105–14. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozłowska H, Baranowska M, Schlicker E et al. Identification of the vasodilatory endothelial cannabinoid receptor in the human pulmonary artery. J Hypertens 2007;25:2240–8. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef7a0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Randall MD, Kendall DA. Involvement of a cannabinoid in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated coronary vasorelaxation. Eur J Pharmacol 1997;335:205–9. 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01237-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romano MR, Lograno MD. Cannabinoid agonists induce relaxation in the bovine ophthalmic artery: evidences for CB1 receptors, nitric oxide and potassium channels. Br J Pharmacol 2006;147:917–25. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sánchez-Pastor E, Andrade F, Sánchez-Pastor JM et al. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 activation by arachidonylcyclopropylamide in rat aortic rings causes vasorelaxation involving calcium-activated potassium channel subunit alpha-1 and calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1C subunit. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;729:100–6. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner JA, Abesser M, Harvey-White J et al. 2-Arachidonylglycerol acting on CB1 cannabinoid receptors mediates delayed cardioprotection induced by nitric oxide in rat isolated hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006;47:650–5. 10.1097/01.fjc.0000211752.08949.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zumbrun EE, Sido JM, Nagarkatti PS et al. Epigenetic regulation of immunological alterations following prenatal exposure to marijuana cannabinoids and its long term consequences in offspring. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2015;10:245–54. 10.1007/s11481-015-9586-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watson CT, Szutorisz H, Garg P et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling reveals epigenetic changes in the rat nucleus accumbens associated with cross-generational effects of adolescent THC exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40: 2993–3005. 10.1038/npp.2015.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malinowska B, Kwolek G, Göthert M. Anandamide and methanandamide induce both vanilloid VR1- and cannabinoid CB1 receptor-mediated changes in heart rate and blood pressure in anaesthetized rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2001;364:562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ralevic V, Kendall DA, Randall MD et al. Cannabinoid modulation of sensory neurotransmission via cannabinoid and vanilloid receptors: roles in regulation of cardiovascular function. Life Sci 2002;71:2577–94. 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02086-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ponto LL, O'Leary DS, Koeppel J et al. Effect of acute marijuana on cardiovascular function and central nervous system pharmacokinetics of [(15)O]water: effect in occasional and chronic users. J Clin Pharmacol 2004;44:751–66. 10.1177/0091270004265699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramesh D, Haney M, Cooper ZD. Marijuana's dose-dependent effects in daily marijuana smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;21:287–93. 10.1037/a0033661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011891supp.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)