Abstract

Objective

The majority of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) remain to be validated despite extensive use in epidemiological research. We therefore examined the positive predictive value (PPV) of cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR.

Design

Population-based validation study.

Setting

1 university hospital and 2 regional hospitals in the Central Denmark Region, 2010–2012.

Participants

For each cardiovascular diagnosis, up to 100 patients from participating hospitals were randomly sampled during the study period using the DNPR.

Main outcome measure

Using medical record review as the reference standard, we examined the PPV for cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR, coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.

Results

A total of 2153 medical records (97% of the total sample) were available for review. The PPVs ranged from 64% to 100%, with a mean PPV of 88%. The PPVs were ≥90% for first-time myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stable angina pectoris, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation or flutter, cardiac arrest, mitral valve regurgitation or stenosis, aortic valve regurgitation or stenosis, pericarditis, hypercholesterolaemia, aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm/dilation and arterial claudication. The PPVs were between 80% and 90% for recurrent myocardial infarction, first-time unstable angina pectoris, pulmonary hypertension, bradycardia, ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation, endocarditis, cardiac tumours, first-time venous thromboembolism and between 70% and 80% for first-time and recurrent admission due to heart failure, first-time dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy and recurrent venous thromboembolism. The PPV for first-time myocarditis was 64%. The PPVs were consistent within age, sex, calendar year and hospital categories.

Conclusions

The validity of cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR is overall high and sufficient for use in research since 2010.

Keywords: CARDIOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first validation study to include all major cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry.

We sampled patients only from hospitals in the Central Denmark Region. However, our results are most likely generalisable to other parts of the country as the Danish healthcare system is homogeneous in structure and practice.

We only validated patients diagnosed during 2010–2012 and therefore cannot extrapolate our results to previous periods.

Introduction

Remarkable improvements have occurred in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases during recent decades.1–4 Still, cardiovascular diseases remain a leading cause of death worldwide,5 underscoring the need for further research. Registries constitute an important source of data for cardiovascular research in Denmark. The key registry is the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR),6 which contains long-term longitudinal data, prospectively collected since 1977. The registry has nationwide coverage of a homogeneous healthcare system with free and equal access and holds the possibility of individual-level data linkage with other registries.7 8 However, the quality of registry-based research largely depends on the validity of the diagnostic codes used. Existing validation studies for cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR have been limited to relatively few diagnoses.6 We therefore conducted a validation study to examine the positive predictive value (PPV) of diagnoses in the DNPR for all major cardiovascular diseases.

Methods

Setting

Denmark is divided into five regions, each of which is representative of the Danish population with respect to demographic and socioeconomic characteristics as well as healthcare usage and medication use.9 Each region typically has one major university hospital (including a high volume cardiac centre) and several smaller regional hospitals. The Danish National Health Service provides free universal tax-supported healthcare, guaranteeing unfettered access to general practitioners and hospitals.6

Study population

We used the DNPR to randomly sample inpatient and outpatient hospital diagnoses from the Central Denmark Region between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012. The Central Denmark Region has a source population of 1.2 million inhabitants. Within the Central Denmark Region, we sampled specifically from the university hospital (Aarhus University Hospital) and two regional hospitals (Regional Hospitals of Randers and Herning).8 The DNPR has recorded data on dates of admission and discharge from all Danish non-psychiatric hospitals since 1977 and on dates of emergency room and outpatient clinic visits since 1995.6 Each hospital discharge or outpatient visit is recorded with one primary diagnosis and one or more secondary diagnoses classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 8th Revision (ICD-8) until the end of 1993 and 10th Revision (ICD-10) thereafter.6

Our study population consisted of patients discharged with a primary or secondary first-time diagnosis from departments of cardiology, internal medicine, acute medicine and neurology in the three hospitals. For myocardial infarction, heart failure and venous thromboembolism, we also validated recurrent events. For most diseases, both inpatient and outpatient diagnoses were included (see online supplementary table S1). However, for diseases expected only to be diagnosed at inpatient admission (eg, myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, cardiac arrest), we only sampled inpatient diagnoses to avoid potential misclassification. Up to 100 patients were sampled from the DNPR for each of the diagnoses, which included first-time acute myocardial infarction (subsequently stratified by ST-elevation (STEMI) and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)), recurrent myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, first-time heart failure, heart failure readmission, arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation or flutter, bradycardia, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, cardiac arrest with indication for resuscitation, endocarditis, myocarditis, pericarditis, first-time venous thromboembolism (subsequently stratified by deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), recurrent venous thromboembolism (subsequently stratified by deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), arterial claudication, hypercholesterolaemia and cardiac tumours. We sampled up to 100 cases for cardiomyopathy (by sampling 20 diagnoses each for dilated, hypertrophic, restrictive, arrhythmogenic right ventricular and takotsubo cardiomyopathy), valvular heart disease (sampling 50 diagnoses each for mitral valve regurgitation or stenosis, and aortic valve regurgitation or stenosis) and aortic diseases (sampling 50 diagnoses each for aortic dissection and aneurysm/dilation).

bmjopen-2016-012832supp.pdf (120.1KB, pdf)

Recurrent myocardial infarction and readmission due to heart failure were defined as the first readmission after the initial diagnosis. Sampling of first-time and recurrent events was independent. Hence, recurrent events could potentially include patients also included in the random sample for validation of first-time events. To avoid situations in which a transfer from one department to another was registered as a new diagnosis, we required that patients should be discharged for >24 hours before readmission could be registered as a true recurrent event. Bradycardia was defined as sinus node dysfunction or atrioventricular block. For venous thromboembolism, we defined recurrent events as admissions occurring >3 months after the initial diagnosis as guidelines recommend at least 3 months of anticoagulant therapy following venous thromboembolism.10 All ICD codes used in the study are provided in online supplementary table S1. The patients were sampled using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Medical record review

Medical record review was used as the reference standard. We did not have access to ECGs or other paraclinical recordings that supported the clinician's decision. However, descriptions of such recordings were available in the medical records and included in the review process. Three physicians (JS, KA and TM) reviewed the medical records and judged whether they confirmed the cardiovascular diagnosis coded in the DNPR. If the diagnosis was not described in the discharge summary or if the discharge summary was not available, the full medical record was reviewed to examine whether the diagnosis code could be confirmed. Review of the discharge summary/medical records began with confirmation of the Civil Personal Register number (unique personal identifier) and discharge date for each hospital contact retrieved from the DNPR. The diagnoses from the discharge summary and/or medical records were then compared with the diagnoses in the DNPR. Events coded in the DNPR as recurrent were considered correct if they were truly new events (for myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism) and for heart failure if the readmission was due to a heart failure exacerbation. If the reviewing physician was uncertain whether the discharge summary or medical record agreed with the ICD-10 code, a second independent review was performed by one of the two other physicians. In case of disagreement, a consensus agreement was reached.

Data were entered into Epidata V.3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark, http://www.epidata.dk) using a medical chart extraction form (see online supplementary table S2).

Statistical analysis

For each diagnosis, we computed the PPV with 95% CIs according to the Wilson score method.11 The PPV was computed as the proportion of diagnoses retrieved from the DNPR that could be confirmed in the discharge summary or medical record. For venous thromboembolism (including deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), we recalculated the PPVs for patients having an ultrasound and/or CT scan recorded in the registry during the index admission and for those who had neither of these registered. To calculate the mean PPV for all cardiovascular diseases, we divided the total number of correct cases by the total number of validated cases. We stratified the analyses by age group (<60 years, 60–80 years and >80 years), sex, calendar year (2010, 2011 and 2012), hospital type (regional or university hospital), type of diagnosis (primary or secondary) and type of hospital contact (inpatient or outpatient). Furthermore, we performed subgroup analyses for myocardial infarction (STEMI and NSTEMI diagnoses) and first-time and recurrent venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism diagnoses).

Results

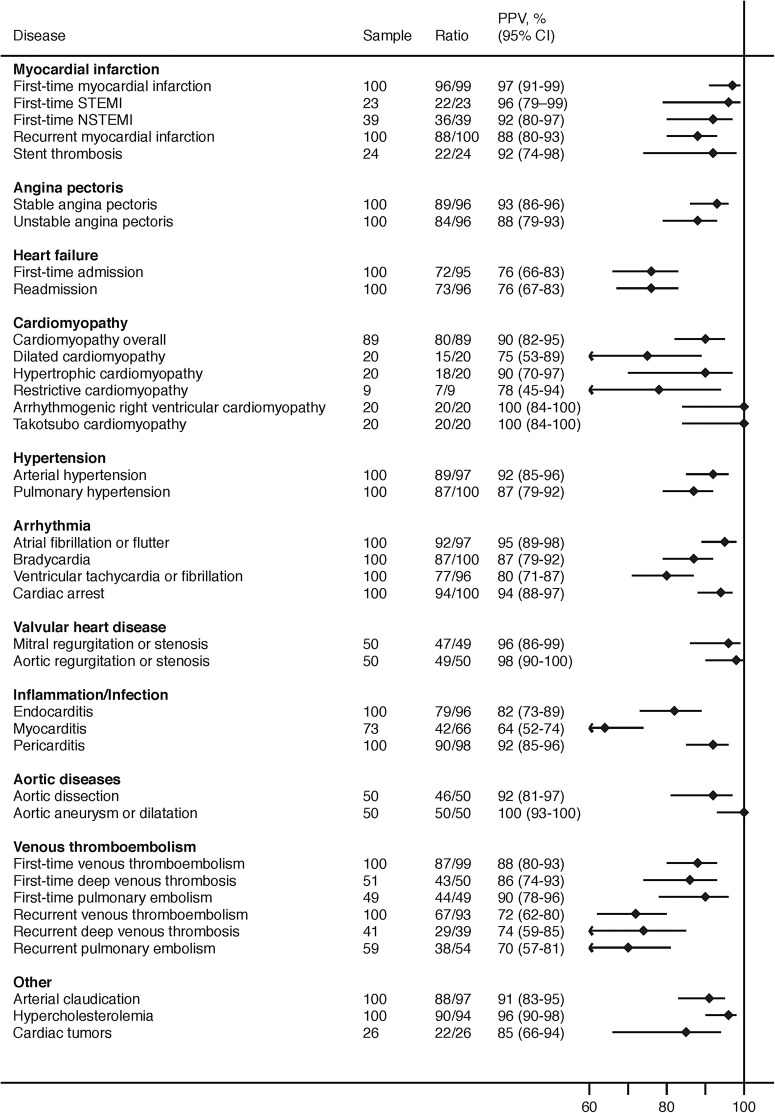

We identified 2212 patients from the DNPR with cardiovascular diagnoses during 2010–2012. Medical records were available for 2153 patients (97% of the total sample). For the most common diseases, 100 patients were sampled; for rare diseases, fewer patients were available for sampling (figure 1). PPVs ranged between 64% and 100% with a mean PPV of 88%. PPVs were ≥90% for first-time myocardial infarction (including STEMI and NSTEMI), stent thrombosis, stable angina pectoris, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation or flutter, cardiac arrest with indication for resuscitation, mitral valve regurgitation or stenosis, aortic valve regurgitation or stenosis, pericarditis, hypercholesterolaemia, aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm/dilation and arterial claudication (figure 1). The distribution of cardiac arrest was 57% out of hospital, 30% inhospital and 13% undetermined. Apart from myocarditis (PPV=64%), the remaining PPVs were between 80% and 90% for recurrent myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris, pulmonary hypertension, bradycardia, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, endocarditis, cardiac tumours, first-time venous thromboembolism and between 70% and 80% for first-time and recurrent admission for heart failure, dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy and recurrent venous thromboembolism. The PPV for venous thromboembolism improved when the following additional criteria were applied: receipt of CT or ultrasound scan during hospitalisation (PPV=91%), and receipt of both a CT and ultrasound scan during hospitalisation (PPV=100%; table 1).

Figure 1.

Positive predictive values of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry. Ratio, denotes confirmed diagnoses/available records; PPV, positive predictive value; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-STEMI.

Table 1.

Positive predictive values of venous thromboembolism diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry, by diagnostic modalities during admission

| Number of patients sampled | Confirmed diagnoses/ available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-time venous thromboembolism | 100 | 87/99 | 88 (80 to 93) |

| No ultrasound or CT scan during admission | 22 | 17/22 | 77 (57 to 90) |

| Ultrasound or CT scan during admission | 77 | 70/77 | 91 (82 to 96) |

| Ultrasound and CT scan during admission | 13 | 13/13 | 100 (77 to 100) |

| Recurrent venous thromboembolism | 100 | 67/93 | 72 (62 to 80) |

| No ultrasound or CT scan during admission | 25 | 11/25 | 44 (27 to 63) |

| Ultrasound or CT scan during admission | 72 | 56/68 | 82 (72 to 90) |

| Ultrasound and CT scan during admission | 7 | 5/7 | 71 (36 to 92) |

The PPVs were consistent within age, sex, calendar year and hospital categories (tables 2 and 3). The stratified analyses by type of diagnosis and type of hospital contact revealed that the main results were driven by primary diagnoses from inpatient admissions. Thus, primary and inpatient diagnoses occurred most frequently, and the PPVs associated with these diagnosis types overall tended to be higher than for secondary and outpatient diagnoses (table 4).

Table 2.

Positive predictive values of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry, by age groups and sex

| <60 years |

60–80 years |

>80 years |

Men |

Women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||||||

| First-time myocardial infarction | 29/30 | 97 (83 to 99) | 47/48 | 98 (89 to 100) | 20/21 | 95 (77 to 99) | 61/63 | 97 (89 to 99) | 35/36 | 97 (86 to 100) |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction | 17/19 | 89 (69 to 97) | 51/57 | 89 (79 to 95) | 20/24 | 83 (64 to 93) | 61/69 | 88 (79 to 94) | 27/31 | 87 (71 to 95) |

| Stent thrombosis | 9/9 | 100 (70 to 100) | 11/13 | 85 (58 to 96) | 2/2 | 100 (34 to 100) | 15/16 | 94 (72 to 99) | 7/8 | 88 (53 to 98) |

| Angina pectoris | ||||||||||

| Stable angina pectoris | 25/29 | 86 (69 to 95) | 51/54 | 94 (85 to 98) | 13/13 | 100 (77 to 100) | 63/69 | 91 (82 to 96) | 26/27 | 96 (82 to 99) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 24/28 | 86 (69 to 94) | 51/57 | 89 (79 to 95) | 9/11 | 82 (52 to 95) | 48/55 | 87 (76 to 94) | 36/41 | 88 (74 to 95) |

| Heart failure | ||||||||||

| First-time heart failure | 13/13 | 100 (77 to 100) | 37/50 | 74 (60 to 84) | 22/32 | 69 (51 to 82) | 50/60 | 83 (72 to 91) | 22/35 | 63 (46 to 77) |

| Readmission for heart failure | 7/14 | 50 (27 to 73) | 42/50 | 84 (71 to 92) | 24/32 | 75 (58 to 87) | 45/56 | 80 (68 to 89) | 28/40 | 70 (55 to 82) |

| Cardiomyopathy | ||||||||||

| Cardiomyopathy overall | 32/33 | 97 (85 to 99) | 40/44 | 91 (79 to 96) | 8/12 | 67 (39 to 86) | 38/44 | 86 (73 to 94) | 42/45 | 93 (82 to 98) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 3/3 | 100 (44 to 100) | 11/13 | 85 (58 to 96) | 1/4 | 25 (5 to 70) | 6/10 | 60 (31 to 83) | 9/10 | 90 (60 to 98) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5/5 | 100 (57 to 100) | 9/10 | 90 (60 to 98) | 4/5 | 80 (38 to 96) | 12/13 | 92 (67 to 99) | 6/7 | 86 (49 to 97) |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 2/3 | 67 (21 to 94) | 5/6 | 83 (44 to 97) | 0/0 | N/A | 4/5 | 80 (38 to 96) | 3/4 | 75 (30 to 95) |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 14/14 | 100 (78 to 100) | 6/6 | 100 (61 to 100) | 0/0 | N/A | 14/14 | 100 (78 to 100) | 6/6 | 100 (61 to 100) |

| Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | 8/8 | 100 (68 to 100) | 9/9 | 100 (70 to 100) | 3/3 | 100 (44 to 100) | 2/2 | 100 (34 to 100) | 18/18 | 100 (82 to 100) |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 20/24 | 83 (64 to 93) | 52/55 | 95 (85 to 98) | 17/18 | 94 (74 to 99) | 48/55 | 87 (76 to 94) | 41/42 | 98 (88 to 100) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 24/28 | 86 (69 to 94) | 41/50 | 82 (69 to 90) | 22/22 | 100 (85 to 100) | 36/41 | 88 (74 to 95) | 51/59 | 86 (75 to 93) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | ||||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 14/15 | 93 (70 to 99) | 49/53 | 92 (82 to 97) | 29/29 | 100 (88 to 100) | 50/53 | 94 (85 to 98) | 42/44 | 95 (85 to 99) |

| Bradycardia | 14/14 | 100 (78 to 100) | 35/40 | 88 (74 to 95) | 38/46 | 83 (69 to 91) | 49/55 | 89 (78 to 95) | 38/45 | 84 (71 to 92) |

| Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation | 27/31 | 87 (71 to 95) | 37/51 | 73 (59 to 83) | 13/14 | 93 (69 to 99) | 50/60 | 83 (72 to 91) | 27/36 | 75 (59 to 86) |

| Cardiac arrest | 31/31 | 100 (89 to 100) | 43/45 | 96 (85 to 99) | 20/24 | 83 (64 to 93) | 69/73 | 95 (87 to 98) | 25/27 | 93 (77 to 98) |

| Valvular heart disease | ||||||||||

| Mitral regurgitation or stenosis | 8/9 | 89 (57 to 98) | 22/23 | 96 (79 to 99) | 17/17 | 100 (82 to 100) | 20/22 | 91 (72 to 97) | 27/27 | 100 (88 to 100) |

| Aortic regurgitation or stenosis | 6/6 | 100 (61 to 100) | 22/23 | 96 (79 to 99) | 21/21 | 100 (85 to 100) | 21/22 | 95 (78 to 99) | 28/28 | 100 (88 to 100) |

| Inflammation/infection | ||||||||||

| Endocarditis | 21/24 | 88 (69 to 96) | 40/47 | 85 (72 to 93) | 18/25 | 72 (52 to 86) | 62/75 | 83 (73 to 90) | 17/21 | 81 (60 to 92) |

| Myocarditis | 33/39 | 85 (70 to 93) | 8/18 | 44 (25 to 66) | 1/9 | 11 (2 to 44) | 30/43 | 70 (55 to 81) | 12/23 | 52 (33 to 71) |

| Pericarditis | 50/55 | 91 (80 to 96) | 36/39 | 92 (80 to 97) | 4/4 | 100 (51 to 100) | 59/65 | 91 (81 to 96) | 31/33 | 94 (80 to 98) |

| Aortic diseases | ||||||||||

| Aortic dissection | 18/19 | 95 (75 to 99) | 24/27 | 89 (72 to 96) | 4/4 | 100 (51 to 100) | 30/31 | 97 (84 to 99) | 16/19 | 84 (62 to 94) |

| Aortic aneurysm/dilation | 4/4 | 100 (51 to 100) | 34/34 | 100 (90 to 100) | 12/12 | 100 (76 to 100) | 31/31 | 100 (89 to 100) | 19/19 | 100 (83 to 100) |

| Venous thromboembolism | ||||||||||

| First-time venous thromboembolism | 25/29 | 86 (69 to 95) | 47/51 | 92 (82 to 97) | 15/19 | 79 (57 to 91) | 36/42 | 86 (72 to 93) | 51/57 | 89 (79 to 95) |

| First-time deep venous thrombosis | 16/19 | 84 (62 to 94) | 22/24 | 92 (74 to 98) | 5/7 | 71 (36 to 92) | 21/23 | 91 (73 to 98) | 22/27 | 81 (63 to 92) |

| First-time pulmonary embolism | 9/10 | 90 (60 to 98) | 25/27 | 93 (77 to 98) | 10/12 | 83 (55 to 95) | 15/19 | 79 (57 to 91) | 29/30 | 97 (83 to 99) |

| Recurrent venous thromboembolism | 18/26 | 69 (50 to 84) | 31/42 | 74 (59 to 85) | 18/25 | 72 (52 to 86) | 40/53 | 75 (62 to 85) | 27/40 | 68 (52 to 80) |

| Recurrent deep venous thrombosis | 12/16 | 75 (51 to 90) | 12/17 | 71 (47 to 87) | 5/6 | 83 (44 to 97) | 18/24 | 75 (55 to 88) | 11/15 | 73 (48 to 89) |

| Recurrent pulmonary embolism | 6/10 | 60 (31 to 83) | 19/25 | 76 (57 to 89) | 13/19 | 68 (46 to 85) | 22/29 | 76 (58 to 88) | 16/25 | 64 (45 to 80) |

| Other | ||||||||||

| Arterial claudication | 10/10 | 100 (72 to 100) | 63/70 | 90 (81 to 95) | 15/17 | 88 (66 to 97) | 49/57 | 86 (75 to 93) | 39/40 | 98 (87 to 100) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 35/37 | 95 (82 to 99) | 44/46 | 96 (85 to 99) | 11/11 | 100 (74 to 100) | 55/58 | 95 (86 to 98) | 35/36 | 97 (86 to 100) |

| Cardiac tumours | 11/11 | 100 (74 to 100) | 10/13 | 77 (50 to 92) | 1/2 | 50 (9 to 91) | 9/11 | 82 (52 to 95) | 13/15 | 87 (62 to 96) |

Table 3.

Positive predictive values of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry, by calendar year and type of hospital

| 2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

University hospital |

Regional hospital |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||||||

| First-time myocardial infarction | 34/35 | 97 (85 to 99) | 28/29 | 97 (83 to 99) | 34/35 | 97 (85 to 99) | 59/61 | 97 (89 to 99) | 37/38 | 97 (87 to 100) |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction | 28/33 | 85 (69 to 93) | 35/38 | 92 (79 to 97) | 25/29 | 86 (69 to 95) | 47/51 | 92 (82 to 97) | 41/49 | 84 (71 to 91) |

| Stent thrombosis | 6/6 | 100 (61 to 100) | 7/9 | 78 (45 to 94) | 9/9 | 100 (70 to 100) | 20/21 | 95 (77 to 99) | 2/3 | 67 (21 to 94) |

| Angina pectoris | ||||||||||

| Stable angina pectoris | 32/35 | 91 (78 to 97) | 27/29 | 93 (78 to 98) | 30/32 | 94 (80 to 98) | 63/68 | 93 (84 to 97) | 26/28 | 93 (77 to 98) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 26/29 | 90 (74 to 96) | 31/36 | 86 (71 to 94) | 27/31 | 87 (71 to 95) | 40/46 | 87 (74 to 94) | 44/50 | 88 (76 to 94) |

| Heart failure | ||||||||||

| First-time heart failure | 25/31 | 81 (64 to 91) | 27/38 | 71 (55 to 83) | 20/26 | 77 (58 to 89) | 29/40 | 73 (57 to 84) | 43/55 | 78 (66 to 87) |

| Readmission for heart failure | 21/28 | 75 (57 to 87) | 30/38 | 79 (64 to 89) | 22/30 | 73 (56 to 86) | 27/37 | 73 (57 to 85) | 46/59 | 78 (66 to 87) |

| Cardiomyopathy | ||||||||||

| Cardiomyopathy overall | 22/25 | 88 (70 to 96) | 22/24 | 92 (74 to 98) | 36/40 | 90 (77 to 96) | 61/66 | 92 (83 to 97) | 19/23 | 83 (63 to 93) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1/2 | 50 (9 to 91) | 6/7 | 86 (49 to 97) | 8/11 | 72 (43 to 90) | 6/8 | 75 (41 to 93) | 9/12 | 75 (47 to 91) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 4/5 | 80 (38 to 96) | 5/5 | 100 (57 to 100) | 9/10 | 90 (60 to 98) | 11/12 | 92 (65 to 99) | 7/8 | 88 (53 to 98) |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 3/4 | 75 (30 to 95) | 1/2 | 50 (9 to 91) | 3/3 | 100 (44 to 100) | 7/9 | 78 (45 to 94) | 0/0 | N/A |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 8/8 | 100 (68 to 100) | 7/7 | 100 (65 to 100) | 5/5 | 100 (57 to 100) | 20/20 | 100 (84 to 100) | 0/0 | N/A |

| Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | 6/6 | 100 (61 to 100) | 3/3 | 100 (44 to 100) | 11/11 | 100 (74 to 100) | 17/17 | 100 (82 to 100) | 3/3 | 100 (44 to 100) |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 14/15 | 93 (70 to 99) | 39/43 | 91 (78 to 96) | 36/39 | 92 (80 to 97) | 35/41 | 85 (72 to 93) | 54/56 | 96 (88 to 99) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 24/28 | 86 (69 to 94) | 26/31 | 84 (67 to 93) | 37/41 | 90 (77 to 96) | 49/60 | 82 (70 to 89) | 38/40 | 95 (84 to 99) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | ||||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 27/29 | 93 (78 to 98) | 30/32 | 94 (80 to 98) | 35/36 | 97 (86 to 100) | 30/33 | 91 (76 to 97) | 62/64 | 97 (89 to 99) |

| Bradycardia | 24/26 | 92 (76 to 98) | 28/35 | 80 (64 to 90) | 35/39 | 90 (76 to 96) | 61/71 | 86 (76 to 92) | 26/29 | 90 (74 to 96) |

| Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation | 23/30 | 77 (59 to 88) | 21/27 | 78 (59 to 89) | 33/39 | 85 (70 to 93) | 49/63 | 78 (66 to 86) | 28/33 | 85 (69 to 93) |

| Cardiac arrest | 29/32 | 91 (76 to 97) | 26/26 | 100 (87 to 100) | 39/42 | 93 (81 to 98) | 72/75 | 96 (89 to 99) | 22/25 | 88 (70 to 96) |

| Valvular heart disease | ||||||||||

| Mitral regurgitation or stenosis | 9/10 | 90 (60 to 98) | 15/16 | 94 (72 to 99) | 23/23 | 100 (86 to 100) | 30/32 | 94 (80 to 98) | 17/17 | 100 (82 to 100) |

| Aortic regurgitation or stenosis | 13/13 | 100 (77 to 100) | 16/16 | 100 (81 to 100) | 20/21 | 95 (77 to 99) | 29/29 | 100 (88 to 100) | 20/21 | 95 (77 to 99) |

| Inflammation/infection | ||||||||||

| Endocarditis | 25/29 | 86 (69 to 95) | 26/29 | 90 (74 to 96) | 28/38 | 74 (58 to 85) | 49/59 | 83 (72 to 91) | 30/37 | 81 (66 to 91) |

| Myocarditis | 14/21 | 67 (45 to 83) | 14/24 | 58 (39 to 76) | 14/21 | 67 (45 to 83) | 33/49 | 67 (53 to 79) | 9/17 | 53 (31 to 74) |

| Pericarditis | 31/36 | 86 (71 to 94) | 30/31 | 97 (84 to 99) | 29/31 | 93 (79 to 98) | 60/67 | 90 (80 to 95) | 30/31 | 97 (84 to 99) |

| Aortic diseases | ||||||||||

| Aortic dissection | 11/14 | 79 (52 to 92) | 16/16 | 100 (81 to 100) | 19/20 | 95 (76 to 99) | 32/36 | 89 (75 to 96) | 14/14 | 100 (78 to 100) |

| Aortic aneurysm/dilation | 13/13 | 100 (77 to 100) | 23/23 | 100 (86 to 100) | 14/14 | 100 (78 to 100) | 36/36 | 100 (90 to 100) | 14/14 | 100 (78 to 100) |

| Venous thromboembolism | ||||||||||

| First-time venous thromboembolism | 25/28 | 89 (73 to 96) | 30/33 | 91 (76 to 97) | 32/38 | 84 (70 to 93) | 28/34 | 82 (66 to 92) | 59/65 | 91 (81 to 96) |

| First-time deep venous thrombosis | 13/15 | 87 (62 to 96) | 13/14 | 93 (69 to 99) | 17/21 | 81 (60 to 92) | 13/16 | 81 (57 to 93) | 30/34 | 88 (73 to 95) |

| First-time pulmonary embolism | 12/13 | 92 (67 to 99) | 17/19 | 89 (69 to 97) | 15/17 | 88 (66 to 97) | 15/18 | 83 (61 to 94) | 29/31 | 94 (79 to 98) |

| Recurrent venous thromboembolism | 22/27 | 81 (63 to 92) | 20/29 | 69 (51 to 83) | 25/37 | 68 (51 to 80) | 25/39 | 64 (48 to 77) | 42/54 | 78 (65 to 87) |

| Recurrent deep venous thrombosis | 9/11 | 82 (52 to 95) | 9/13 | 69 (42 to 87) | 11/15 | 73 (48 to 89) | 6/10 | 60 (31 to 83) | 23/29 | 79 (62 to 90) |

| Recurrent pulmonary embolism | 13/16 | 81 (57 to 93) | 11/16 | 69 (44 to 86) | 14/22 | 64 (43 to 80) | 19/29 | 66 (47 to 80) | 19/25 | 76 (57 to 89) |

| Other | ||||||||||

| Arterial claudication | 18/20 | 90 (70 to 97) | 33/37 | 89 (75 to 96) | 37/40 | 93 (80 to 97) | 86/95 | 91 (83 to 95) | 2/2 | 100 (34 to 100) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 27/30 | 90 (74 to 97) | 30/31 | 97 (84 to 99) | 33/33 | 100 (90 to 100) | 48/51 | 94 (84 to 98) | 42/43 | 98 (88 to 100) |

| Cardiac tumours | 2/3 | 67 (21 to 94) | 9/11 | 82 (52 to 95) | 11/12 | 92 (65 to 99) | 17/18 | 94 (74 to 99) | 5/8 | 63 (31 to 86) |

Table 4.

Positive predictive values of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry, by type of diagnosis

| Primary diagnosis |

Secondary diagnosis |

Inpatient diagnosis |

Outpatient diagnosis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | Confirmed diagnoses/available records | Positive predictive value, % (95% CI) | |

| Myocardial infarction | ||||||||

| First-time myocardial infarction | 88/89 | 99 (94 to 100) | 8/10 | 80 (49 to 94) | – | – | – | – |

| Recurrent myocardial infarction | 88/100 | 88 (80 to 93) | 0/0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Stent thrombosis | 14/15 | 93 (70 to 99) | 8/9 | 89 (57 to 98) | – | – | – | – |

| Angina pectoris | ||||||||

| Stable angina pectoris | 68/73 | 93 (85 to 97) | 21/23 | 91 (73 to 98) | – | – | – | – |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 80/90 | 89 (81 to 94) | 4/6 | 67 (30 to 90) | – | – | – | – |

| Heart failure | ||||||||

| First-time heart failure | 31/39 | 79 (64 to 89) | 41/56 | 73 (60 to 83) | – | – | – | – |

| Readmission for heart failure | 73/96 | 76 (67 to 83) | 0/0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cardiomyopathy | ||||||||

| Cardiomyopathy overall | 56/61 | 92 (82 to 96) | 24/37 | 65 (49 to 78) | 34/41 | 83 (69 to 91) | 26/27 | 96 (82 to 99) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 8/10 | 80 (49 to 94) | 7/10 | 70 (40 to 89) | 11/15 | 73 (48 to 89) | 4/5 | 80 (38 to 96) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 11/12 | 92 (65 to 99) | 7/8 | 88 (53 to 98) | 8/10 | 80 (49 to 94) | 10/10 | 100 (72 to 100) |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 6/8 | 75 (41 to 93) | 1/1 | 100 (21 to 100) | 7/8 | 88 (53 to 98) | 0/1 | 0 (0 to 79) |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 11/11 | 100 (74 to 100) | 9/9 | 100 (70 to 100) | 8/8 | 100 (68 to 100) | 12/12 | 100 (76 to 100) |

| Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | 20/20 | 100 (84 to 100) | 0/0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Arterial hypertension | 30/33 | 91 (76 to 97) | 59/64 | 92 (83 to 97) | 49/53 | 92 (82 to 97) | 40/44 | 91 (79 to 96) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 54/61 | 89 (78 to 94) | 33/39 | 85 (70 to 93) | 58/60 | 97 (89 to 99) | 29/40 | 73 (57 to 84) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | ||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 55/58 | 95 (86 to 98) | 37/39 | 95 (83 to 99) | 75/75 | 100 (95 to 100) | 17/22 | 77 (57 to 90) |

| Bradycardia | 75/79 | 95 (88 to 98) | 12/21 | 57 (37 to 76) | 78/85 | 92 (84 to 96) | 9/15 | 60 (36 to 80) |

| Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation | 46/58 | 79 (67 to 88) | 31/38 | 82 (67 to 91) | 70/77 | 91 (82 to 96) | 7/19 | 37 (19 to 59) |

| Cardiac arrest | 66/67 | 99 (92 to 100) | 28/33 | 85 (69 to 93) | – | – | – | – |

| Valvular heart disease | ||||||||

| Mitral regurgitation or stenosis | 19/20 | 95 (76 to 99) | 28/29 | 97 (83 to 99) | 21/21 | 100 (85 to 100) | 26/28 | 93 (77 to 98) |

| Aortic regurgitation or stenosis | 29/30 | 97 (83 to 99) | 20/20 | 100 (84 to 100) | 31/31 | 100 (89 to 100) | 18/19 | 95 (75 to 99) |

| Inflammation/infection | ||||||||

| Endocarditis | 73/86 | 85 (76 to 91) | 6/10 | 60 (31 to 83) | 75/90 | 83 (74 to 90) | 4/6 | 67 (30 to 90) |

| Myocarditis | 33/41 | 80 (66 to 90) | 9/25 | 36 (20 to 55) | 37/59 | 63 (50 to 74) | 5/7 | 71 (36 to 92) |

| Pericarditis | 76/82 | 93 (85 to 97) | 14/16 | 88 (64 to 97) | 74/76 | 97 (91 to 99) | 16/22 | 73 (52 to 87) |

| Aortic diseases | ||||||||

| Aortic dissection | 45/48 | 94 (83 to 98) | 1/2 | 50 (9 to 91) | – | – | – | – |

| Aortic aneurysm/dilation | 37/37 | 100 (91 to 100) | 13/13 | 100 (77 to 100) | 20/20 | 100 (84 to 100) | 30/30 | 100 (89 to 100) |

| Venous thromboembolism | ||||||||

| First-time venous thromboembolism | 76/84 | 90 (82 to 95) | 11/15 | 73 (48 to 89) | 81/90 | 90 (82 to 95) | 6/9 | 67 (35 to 88) |

| First-time deep venous thrombosis | 38/44 | 86 (73 to 94) | 5/6 | 83 (44 to 97) | 38/43 | 88 (76 to 95) | 5/7 | 71 (36 to 92) |

| First-time pulmonary embolism | 38/40 | 95 (84 to 99) | 6/9 | 67 (35 to 88) | 43/47 | 91 (80 to 97) | 1/2 | 50 (9 to 91) |

| Recurrent venous thromboembolism | 65/77 | 84 (75 to 91) | 2/16 | 13 (4 to 36) | – | – | – | – |

| Recurrent deep venous thrombosis | 29/36 | 81 (65 to 90) | 0/3 | 0 (0 to 56) | – | – | – | – |

| Recurrent pulmonary embolism | 36/41 | 88 (74 to 95) | 2/13 | 15 (4 to 42) | – | – | – | – |

| Other | ||||||||

| Arterial claudication | 83/92 | 90 (82 to 44) | 5/5 | 100 (57 to 100) | 15/17 | 88 (66 to 97) | 73/80 | 91 (83 to 96) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 17/17 | 100 (82 to 100) | 73/77 | 95 (87 to 98) | 62/64 | 97 (89 to 99) | 28/30 | 93 (79 to 98) |

| Cardiac tumours | 16/18 | 89 (67 to 97) | 6/8 | 75 (41 to 93) | 19/23 | 83 (63 to 93) | 3/3 | 100 (44 to 100) |

Discussion

The DNPR accurately recorded diagnoses of the most common cardiovascular diseases during 2010–2012, with the PPV exceeding 90% for myocardial infarction, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation or flutter, valvular heart disease, aortic diseases and first-time venous thromboembolism. As an exception among the most frequent diseases, the PPV for heart failure was lower. For less common conditions, the PPV varied from 64% for myocarditis to 100% for takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The PPV for recurrent myocardial infarction was 88%, but somewhat lower for readmission for heart failure (76%) and recurrent venous thromboembolism (72%). The lower PPVs for recurrent events are most likely influenced by secondary recordings of the initial event as part of follow-up visits or during successive hospital contacts without the occurrence of a truly new event. The results were consistent in age, sex and calendar year categories.

This is the first validation study to include all major cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR. Comparing our results with previous Danish validation studies, it is apparent that the PPVs have improved over time for many cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR.6 This may be explained by increased awareness of correct coding, implementation of clear guidelines and definitions of individual diseases, and improved availability of diagnostic modalities.6 Thus, the PPV of coding has improved for myocardial infarction (PPV=100% during 1996–2009,12 98% during 1998–2007,13 92% during 1993–200314 and 93% during 1982–1991,15) arterial hypertension (PPV=88% during 1977–201016 and ≈50% during 1990–199317) and first-time venous thromboembolism (PPV=90% during 2004–201218 and 75% during 1994–200619). The PPVs were overall in line with previous studies for heart failure (PPV=78% during 2005–200720 and 100% during 1998–200713), atrial fibrillation or flutter (PPV=94% during 1993–2009,21 99% during 1980–200222 and 97% during 1980–200223) and recurrent venous thromboembolism (PPV=79% during 2004–2012 with CT or ultrasound scan during admission and anticoagulant treatment 30 days after admission18). Previous studies reported markedly lower PPVs than our findings for unstable angina pectoris (PPV=42% during 1993–200314) and cardiac arrest (PPV=50% during 1993–200314). The finding of lower PPV for cardiac arrest in the previous study14 may be explained by a small sample size (n=42) and their inclusion of emergency department and outpatient diagnoses, whereas we restricted to inpatient diagnoses. Moreover, the previous study is more than 10 years old and changes in coding practice may also account for part of the difference. For unstable angina pectoris,14 the study period of the previous study ended in 2003, that is, shortly after the redefinition of myocardial infarction in 2000, which included troponin release as an absolute criterion.24 This made the discrimination between unstable angina pectoris and myocardial infarction easier and most likely explains the higher PPV found in our study. To the best of our knowledge, the validity of the remaining diagnoses included in our study has not been assessed before.

Several limitations should be considered. Cautious interpretation of the PPV is warranted for diagnoses with sample sizes below 100. These include subgroups of an overall diagnosis and rare diagnoses with less than 100 cases diagnosed during the study period. Original recordings from diagnostic modalities such as ECG and echocardiography were not available. Therefore, the confirmation of the diagnoses was based solely on descriptions of such recordings included in the discharge summary or medical record. This limits the rigorousness of case validation and also could potentially lead to different interpretations between reviewers. We examined patients admitted to hospitals only in the Central Denmark Region. However, our results are most likely generalisable to other parts of the country as the Danish healthcare system is homogeneous in structure and practice.9 Although some diagnoses (eg, myocardial infarction) have shown consistently high validity across countries despite different registry types and coding systems,6 12 25 it should be noted that our findings may not per se be generalisable to all countries where coding systems, coding practice, disease definitions and diagnostics differ.

In this study, we chose the PPV as the measure of validity. The PPV is correlated with disease prevalence and is dependent on specificity. However, sensitivity, specificity and negative predictive value could not be calculated because the data were sampled from the codes pertinent to the diagnosis of interest. The importance of the different measures of data quality depends on the study question and thus the design. A high PPV is important, for example, when identifying patient cohorts in prognosis studies, but cannot stand alone, for example, when identifying disease incidence. Future studies identifying cardiovascular diseases from diagnoses in the DNPR should consider the possibility that differential misclassification may occur between exposure groups (eg, if the exposure is diabetes, these patients may be more prone to have a given outcome registered due to detection bias and hence have a falsely increased risk of the outcome). Also, since diagnoses were only validated during 2010–2012, we cannot necessarily extrapolate our results to previous periods due to potential temporal differences in PPVs as exemplified above.

Conclusion

The validity of cardiovascular diagnoses in the DNPR is overall high, and for the vast majority of diseases it is sufficient for use in research since 2010.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hanne Moeslund Madsen and Henriette Kristoffersen for practical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS, HTS, JS and KA conceived the study idea and designed the study. TF sampled the patients. JS, KA and TM reviewed all medical records. JS performed the statistical analysis. All authors analysed and interpreted the data. JS wrote the initial draft. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and the Programme for Clinical Research Infrastructure (PROCRIN) established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: In accordance with Danish law governing analysis of registry data, no Ethics Committee approval was required. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record number: 1-16-02-1-08) and the chief physicians of participating departments, as part of quality control.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2012;366:54–63. 10.1056/NEJMra1112570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt M, Jacobsen JB, Lash TL et al. 25 year trends in first time hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction, subsequent short and long term mortality, and the prognostic impact of sex and comorbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e356 10.1136/bmj.e356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Søgaard KK, Schmidt M, Pedersen L et al. 30-year mortality after venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. Circulation 2014;130:829–36. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt M, Ulrichsen SP, Pedersen L et al. Thirty-year trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates and the prognostic impact of co-morbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:490–9. 10.1002/ejhf.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sørensen HT. Regional administrative health registries as a resource in clinical epidemiology. A study of options, strengths, limitations and data quality provided with examples of use. Int J Risk Saf Med 1997;10:1–22. 10.3233/JRS-1997-10101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriksen DP, Rasmussen L, Hansen MR et al. Comparison of the five danish regions regarding demographic characteristics, healthcare utilization, and medication use—a descriptive cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0140197 10.1371/journal.pone.0140197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3033–69, 3069a–3069k 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Stat Assoc 1927;22:209–12. 10.1080/01621459.1927.10502953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coloma PM, Valkhoff VE, Mazzaglia G et al. Identification of acute myocardial infarction from electronic healthcare records using different disease coding systems: a validation study in three European countries. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002862 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:83 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joensen AM, Jensen MK, Overvad K et al. Predictive values of acute coronary syndrome discharge diagnoses differed in the Danish National Patient Registry. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:188–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madsen M, Davidsen M, Rasmussen S et al. The validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in routine statistics: a comparison of mortality and hospital discharge data with the Danish MONICA registry. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:124–30. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00591-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt M, Johannesdottir SA, Lemeshow S et al. Obesity in young men, and individual and combined risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity and death before 55 years of age: a Danish 33-year follow-up study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002698 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen HW, Tüchsen F, Jensen MV. Validiteten af diagnosen essentiel hypertension i Landspatientregistret. Ugeskr Laeg 1996;158:163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt M, Cannegieter SC, Johannesdottir SA et al. Statin use and venous thromboembolism recurrence: a combined nationwide cohort and nested case–control study. J Thromb Haemost 2014;12:1207–15. 10.1111/jth.12604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Severinsen MT, Kristensen SR, Overvad K et al. Venous thromboembolism discharge diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry should be used with caution. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:223–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mard S, Nielsen FE. Positive predictive value and impact of misdiagnosis of a heart failure diagnosis in administrative registers among patients admitted to a University Hospital cardiac care unit. Clin Epidemiol 2010;2:235–9. 10.2147/CLEP.S12457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rix TA, Riahi S, Overvad K et al. Validity of the diagnoses atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in a Danish patient registry. Scand Cardiovasc J 2012;46:149–53. 10.3109/14017431.2012.673728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frost L, Andersen LV, Vestergaard P et al. Trend in mortality after stroke with atrial fibrillation. Am J Med 2007;120:47–53. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost L, Vestergaard P. Alcohol and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: a cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1993–8. 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E et al. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:959–69. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrett E, Shah AD, Boggon R et al. Completeness and diagnostic validity of recording acute myocardial infarction events in primary care, hospital care, disease registry, and national mortality records: cohort study. BMJ 2013;346:f2350 10.1136/bmj.f2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012832supp.pdf (120.1KB, pdf)