Abstract

Objectives

To describe the impact of Street Triage (ST) on the number and rate of Section 136 Mental Health Act (S136) detentions in one NHS Mental Health and Disability Trust (Northumberland, Tyne and Wear (NTW)).

Design

Comparative descriptive study of numbers and rates of S136 detentions prior to and following the introduction of ST in NTW. More detailed data were obtained from one local authority in the NTW area.

Setting

NTW, a secondary care NHS Foundation Trust providing mental health and disability services in the north-east of England, in conjunction with Northumbria Police Service.

Participants

People being detained under S136 Mental Health Act (MHA). Routine data on S136 detentions and ST interventions were obtained from NTW, Northumbria Police, Sunderland Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Sunderland Local Authority.

Interventions

Introduction of a ST service in NTW. The main outcome measures were routinely collected data on the number and rate of ST interventions as well as patterns of the numbers and rates of S136 detentions. These were collected retrospectively.

Results

The annual rate of S136 detentions reduced by 56% in the first year of ST (from 59.8 per 100 000 population to 26.4 per 100 000). There was a linear relationship between the rate of ST in each locality and the reduction in rate of S136 detentions. There were 1623 ST contacts in the first 3 localities to have a ST service during its first year; there were also 403 fewer S136 detentions. Data from Sunderland indicate a 78% reduction in S136 use and a significant reduction in the number and proportion of adult admissions that originated from S136 detentions.

Conclusions

There is evidence to support the hypothesis that ST decreases the rate of s136 detention. When operating across the whole of NTW, ST resulted in 50 fewer S136 detentions a month, which represents a substantial reduction.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study reports the effects of Street Triage (ST) on Section 136 detentions in a large NHS Mental Health and Disability Trust catchment area. It covers a larger population area than previous studies of ST and Section 136 (1.4 million inhabitants).

A strength is that three independent data sources were used in this study; Northumbria Police for S136 detentions; the NHS for ST and A&E use and Sunderland Local Authority for S136 assessments.

A limitation is that the data used were routinely recorded and collected retrospectively. There is no information on diagnosis. There is no recorded information from police officers about which of the ST contacts prevented a S136 detention.

Owing to the nature of the study, it was not possible to control for other changes in the delivery of mental health services in the area. This included the closure of a hospital site which involved the loss of three acute adult wards and one S136 suite.

This study contains a natural control group in the analysis allowing comparison of the effects of the intervention to ‘treatment as usual’ due to the phased introduction of ST.

Background

Section 136 (S136) of the Mental Health Act (1983) (MHA)1 is a police power. It is defined in the recently revised MHA Code of Practice as: “an emergency power which allows for the removal of a person…to a place of safety, if the person appears to the police officer to be suffering from mental disorder and to be in immediate need of care and control”.2 The place of safety is usually in the local psychiatric hospital, but can also be in Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments and police cells. Once in the place of safety, the person is assessed by mental health professionals.

S136 detentions can result in three broad outcomes once assessed by those professionals: involuntarily admission to a psychiatric hospital under the MHA; voluntary admission to hospital or discharge to community follow-up. This community follow-up could be by a crisis home treatment team, a community mental health team, a third sector organisation or discharge back to primary care.

This power can be used by the police when the person is in a public place; it is not used in private places or dwellings. Two key problems with its use have become apparent over recent years. First is the escalating use of S136 detention3 with evidence that this power is being used inappropriately to ensure urgent access to mental health services or in situations where a person is voluntarily seeking help. Second is the recognition that the use of this power, in particular where a police station is used as the place of safety, can be a prolonged, distressing and avoidably traumatising experience for the person detained.4 5 A recent retrospective cohort study found substantial amounts of substance misuse and suicidal ideation among people detained under S136.6

In 2014 23 National Health, Social Care, emergency services and other statutory/voluntary organisations committed to the principles and aims of the Crisis Care Concordat. One central commitment was that Police, Social Care and Health Services would improve cooperation and systems pertaining to the management of people presenting in ‘crisis’.7

One proposal within this report was the development of ‘street triage’ (ST) for people coming to the attention of the police, either through a jointly shared telephone triage service or through the implementation of mobile ST teams. ST originated in the USA in the late 1980s. Following the shooting by police of a mentally disordered person in Memphis, Tennessee, Crisis Intervention Teams (CITs) were established, involving training for police officers in the signs and symptoms of mental disorder.8 In the UK, ST teams typically comprise a Police Officer and Mental Health Clinician working together to attend incidents where there are concerns about the mental state of a person reported to the police. Such situations might ordinarily culminate in the police attending alone and considering the use of S136 powers. Early pilots of different ST models have reported varying degrees of success, with positive impact on the S136 pathway or reduction in numbers of S136 detentions.9–12

In September 2014, a ST service was implemented in the South of Tyne locality of NTW; the North of Tyne ST service started 10 months later in July 2015. NTW ST services comprised a mental health nurse working alongside a dedicated police officer in mobile community units. ST operated between 10:00 until 03:00 the following morning, 7 days a week.

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the following outcomes of the ST service in Northumberland, Tyne and Wear Mental Health Foundation Trust (NTW):

To measure the rate of ST and any change in the rate/number of S136 detentions.

To focus on the South of Tyne area in NTW and investigate whether the changes in the rate/number of S136 detentions were incremental in the first year of ST.

To focus on one specific locality in the South of Tyne area—Sunderland which is an urban locality—and to measure changes in the overall rates of detention under the MHA, rates of admission to hospital for working age adults and attendance at the local A&E department.

Methods

A comparative descriptive study was undertaken, using retrospectively collected data obtained from three sources involved in S136 detentions and ST:

Northumbria Police.

The NHS including the mental health service provider (NTW) and one Accident and Emergency Department (Sunderland Royal Hospital).

The social work department of one local authority (Sunderland).

The police provided data on S136 detentions for all six NTW localities: three North of Tyne (Newcastle, Northumberland and North Tyneside), and three South of Tyne (Sunderland, South Tyneside and Gateshead). These data comprised the monthly number of S136 detentions between September 2013 and September 2015. Data were collected by the police as a part of their own evaluation of ST.

Data obtained from NTW comprised the number of ST contacts according to the clinical commissioning group (CCG) of the person contacted by the ST service. The number of admissions for working age adults was also obtained.

Comprehensive data were available from the Sunderland Local Authority. This included all assessments under the MHA including S136 assessments that involved an Approved Mental Health Professional (AMHP) from Sunderland as well as the age category of the patient, the setting and outcome of these assessments. Data from Sunderland Royal Hospital included the total number of attendances at A&E and, of those, the number who had attended with police. Sunderland was chosen for more detailed analysis due to ease of access to data by clinicians and allied professionals involved in this project. Furthermore, there was a high level of interest shown by the manager of the local mental health social work team in exploring changes in the use of S136 in this locality.

Data analysis

The absolute numbers of S136 detentions and ST contacts were collected and percentage changes were calculated. Total number of ST contacts and S136 detentions were calculated in 3-month blocks. This enabled them to be directly compared with the same corresponding three-month block in the previous year. χ2 tests were used to analyse changes. In addition, the number of ST contacts in an area were compared with the change in the number of S136 detentions. This ratio was calculated as a measure of ‘number needed to triage’ for one reduction in S136 detentions. Population data from the 2011 census13 were used to calculate the rate of S136 detentions and ST contacts per 100 000 whole population in each locality and across the whole area covered by NTW. Absolute and percentage changes in rates were calculated, and parametric tests were used to analyse changes and associations.

Results

Results describing the impact of ST are presented in three sections:

Data relating to S136 detentions and ST contacts across the whole NTW Trust area from September 2013 to August 2015.

Observed trends in S136 contacts in the South of Tyne locality in the first year of ST (September 2014 to August 2015).

Detailed results describing the impact of S136 contacts from the Sunderland area using local authority data.

Monthly number and annual rate of Section 136 detentions before and after ST across the NTW Trust area

In the 12 months prior to the initiation of ST (September 2013 to August 2014), the mean monthly number of S136 detentions across NTW was 70.8 (SD=11.0). When ST was introduced South of Tyne, the mean across NTW fell to 35.5 (September 2014 to June 2015—SD=8.5), a 49.9% reduction. From July 2015, ST was in operation South and North of the Tyne. The mean monthly number of S136 detentions fell further to 18.0 over the following 4 months (SD=2.2), a 74.9% overall reduction across NTW.

During the first 10 months of ST operating only in the South of Tyne (September 2014 to June 2015), the number of S136 detentions in the South of Tyne reduced by 75%; however, S136 detentions in the North of Tyne, where no ST was yet in operation, fell by only 3% (χ2=102.1, df=1, p<0.001).

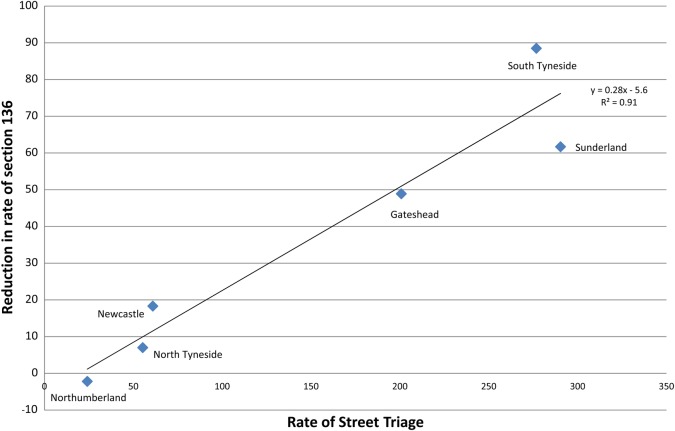

During first year, the rate of ST was 138.7 per 100 000 population. The rate of S136 detentions in NTW fell from 59.8 per 100 000 population prior to the introduction of ST, to 26.4 per 100 000 in its first year, a 55.9% reduction. There was a significant correlation (r=0.96, N=6, p=0.003) between the rate of ST and the reduction in rate of S136 detentions in each of the six localities (see figure 1). This indicates that the higher the rate of ST in a locality, the greater the reduction in the rate of S136 detentions in the same locality. Linear regression indicated an association between three and a half ST contacts and one fewer S136 detention (R2=0.91, F(1,4)=41.8, p=0.003).

Figure 1.

Rate of street triage contacts and reduction in rate of Section 136 detention per 100 000 population in the six localities Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust. Data are the first year following the phased implementation of street triage in 2014/2015 when street triage first started operating South of Tyne (South Tyneside, Sunderland and Gateshead) and 10 months later started operating North of Tyne (Northumberland, Newcastle and North Tyneside).

Change in Section 136 detentions in the three South of Tyne localities (Gateshead, South Tyneside and Sunderland) over the first year of ST

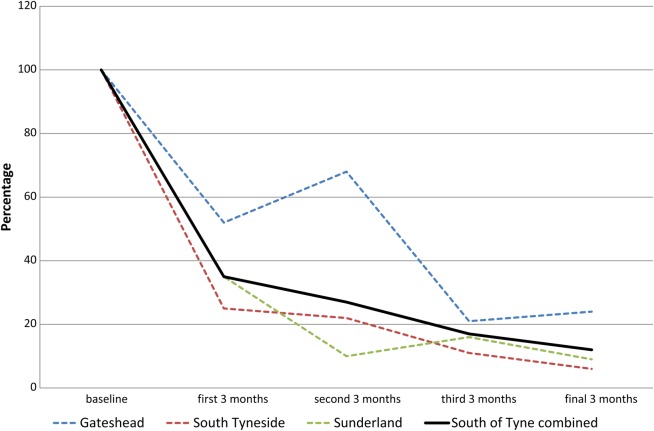

In the three South of Tyne localities, there was a progressive reduction in the number of S136 detentions during each 3-month period in the first year of ST compared to the previous year (see figure 2, and see online supplementary appendix 1 for numbers). The reductions were as follows: 65% reduction in first 3 months; 73% in second 3 months; 83% in third 3 months and 88% in final 3 months (χ2=16.2, df=3, p=0.001).

Figure 2.

The number of Section 136 detentions shown as a percentage of the number in the same 3 months 1 year previously. The year has been divided up into four 3-month periods in the first year of street triage starting in September 2014. Data are also shown for each of the three localities in the South of Tyne separately and combined.

bmjopen-2016-011837supp_appendix.pdf (247.1KB, pdf)

In the first year, there were 1623 ST contacts for South of Tyne residents, and 403 fewer S136 detentions compared with the previous year. This gives a ratio of 4:1 or four STs for one fewer S136 detention. This can be conceived of as a ‘number needed to triage’ of 4. In the first 3 months, the number needed to triage was 4.7 (range: 4.2 in Sunderland to 5.5 in South Tyneside) and had reduced to 3.5 in the final 3 months (range: 2.2 in South Tyneside to 4.2 in Gateshead and Sunderland—see online supplementary appendix 1.)

The number, setting and outcome of Section 136 assessments in one locality (Sunderland)

Sunderland is one of the three South of Tyne localities for which more detailed data were available. The mean monthly number of S136 assessments recorded by Sunderland Local Authority fell from 15.4 before to 3.3 following the introduction of ST (78% reduction). In the 24 months prior to ST, only 5% of such detentions occurred in police stations (about nine per year). In the 13 months following ST implementation, there was only one detention (2%) in police cells which was in the first month of ST (table 1.)

Table 1.

The number and monthly average of Section 136 assessments recorded by Sunderland Local Authority, the setting of these assessments and the proportions that resulted in detention in hospital, voluntary admission and no admission

| Before street triage |

After street triage |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Monthly average (SD) | Number (%) | Monthly average (SD) | Per cent change in monthly average | Change in proportion of total (95% CI) | |

| Section 136 assessment setting | Number of months=24 | Number of months=13 | ||||

| Hospital | 351 (95) | 14.6 (3.8) | 42 (98) | 3.2 (3.0) | −78 | |

| Police station | 18 (5) | 0.8 (1.1) | 1 (2) | 0.1 (0.3) | −90 | −3% (−8 to +2%) |

| Total 136 assessments | 369 (100) | 15.4 (3.9) | 43 (100) | 3.3 (3.5) | −78 | p>0.05 |

| Section 136 outcomes | Number of months=24 | Number of months=13 | ||||

| Detention in hospital | 56 (15) | 2.3 (1.8) | 8 (19) | 0.6 (1.1) | −74 | +4% |

| Voluntary admission | 119 (32) | 5.0 (2.1) | 9 (21) | 0.7 (1.3) | −86 | −11% |

| No admission | 194 (53) | 8.1 (3.3) | 26 (60) | 2.0 (2.3) | −77 | +8% |

| Total | 369 (100) | 43 (100) | All p>0.05 | |||

| Working age adult admissions | Number of months=20 | Number of months=12 | ||||

| Admissions from s136 | 138 (18) | 6.9 (2.2) | 13 (4) | 1.1 (1.5) | −84 | −14% |

| Other admissions | 650 (82) | 32.5 (6.3) | 323 (96) | 26.9 (5.2) | −17 | p<0.001 |

| All admissions | 788 (100) | 39.4 (7.1) | 336 (100) | 28.0 (5.4) | −29 | |

The majority of S136 assessments occurred in the dedicated S136 suite in the psychiatric hospital in Sunderland before and following the implementation of ST (89% vs 93%). Approximately one S136 assessment per month took place in the A&E Department at Sunderland Royal Hospital in the year prior to ST. In the first year of ST, there were only two S136 assessments at A&E. This reduction occurred as the total number of attendances at A&E increased by 14%, and attendances at A&E with police (other than S136) increased by 4% (table 2).

Table 2.

A&E attendances at Sunderland Royal Infirmary in the year before and after street triage was implemented

| Type of A&E attendance | Number of attendances September 2013–August 2014 |

Number of attendances September 2014–August 2015 |

Percentage change | χ2 test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 136 with police | 13 | 2 | −85% | χ2=9 514 993, df=2, p<0.001 |

| Other attendance with police | 849 | 886 | +4% | |

| All other attendances | 93 924 | 107 187 | +14% | |

| Total attendances | 94 786 | 108 075 | +14% |

Despite the significant reduction in the rate of S136 detentions, the outcomes of these assessments did not change significantly after ST implementation. Just over 50% of assessments resulted in no admissions before and after ST. The next most common outcome was voluntary admission—accounting for 32% of the assessments before and 21% of assessments after ST was operating. The proportion of assessments that resulted in detention in hospital was the least common of the three outcomes and increased non-significantly from 15% before 19% after ST was operating (χ2=1.8, df=2, p=0.41—see table 1).

The total number of admissions to acute adult wards (typically for patients aged 18–65 years of age) voluntary and involuntary, from the Sunderland area fell by 29% in the first year of ST. Admissions resulting from S136 detentions fell by 84%, compared with a 17% reduction in admissions where S136 was not a factor (χ2 37.7, df=1, p<0.01) (see table 1).

The number of adults from the Sunderland area under the age of 65 detained under any civil sections of the MHA also fell for the same periods prior to and after ST implementation. Short-term detentions (Sections 4 and 136) fell by 72%; medium-term to long-term detentions (Sections 2 and 3) fell by 21% (see table 2). While the monthly number of S136 assessments fell by 78%, the number of Section 4 detentions increased by a similar amount, albeit from a much lower baseline. In terms of medium-term to long-term detention sections, the use of Section 2 (up to 28 days) fell by 28%, while the use of Section 3 detentions (initially 6 months, thereafter renewable) did not change (2% reduction) (table 3).

Table 3.

Monthly number and mean Mental Health Act assessments for short-term sections (136 and 4) and medium-term to long-term sections (2 and 3) for those aged 18–65 years in Sunderland

| Monthly average (SD) before street triage (N=24) | Monthly average (SD) after street triage (N=13) | Per cent change in monthly average | t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term sections (72 hours) | ||||

| Section 136 | 15.3 (4.1) | 3.3 (3.7) | −78 | t=8.9, p<0.001 |

| Section 4 | 0.6 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.9) | +72 | t=1.6, p=0.13 |

| Total | 15.9 (4.3) | 4.4(3.9) | −72 | t=8.0, p<0.001 |

| Medium-term to long-term sections (28 days+) | (N=24) | (N=13) | ||

| Section 2 (28 days) | 11.2 (4.6) | 8.1 (2.3) | −28 | t=2.2, p=0.03 |

| Section 3 (6 months+) | 4.5 (3.1) | 4.5 (2.4) | −2 | t=0.1, p=0.94 |

| Total | 15.8 (7.0) | 12.5 (3.8) | −21 | t=1.5, p=0.13 |

Discussion

We found a reduction in the rate and number of S136 detentions following the introduction of ST. This applied to S136 detentions in police custody, A&E and S136 suites. The reduction in S136 only occurred when ST was operating in that particular locale, and the more ST that was delivered, the greater was the reduction. This was a very strong association between the rate of ST in a locality and the reduction in the rate of S136 detentions; the linear association suggests a dose–response relationship between the two. The effect of ST was immediate with the number of S136 detentions falling as soon as ST was introduced and steadily continuing during the first year. There were four ST contacts for every one fewer S136 detention. The outcomes of S136 assessments did not change, but among all of the working age adult admissions there was a reduction in admissions that followed a S136 assessment.

The results support the hypothesis that ST leads to a reduction in S136 detentions. The idea has validity as ST was specifically introduced to address the dramatic increase in the use of S136 in recent years.

Limitations

Owing to the nature of the study, it was not possible to control for other changes in the delivery of mental health services in the area. There were substantial changes in services for working age adults which included the closure of a two hospital sites and their re-provision in one new hospital with a reduction in the number of beds and one less S136 suite. This study reports on data from one discrete region in the North East of England. The data should be interpreted in this context, and studies across other geographical locations are required to ascertain their generalisability.

A further limitation is that the data used were routinely recorded and collected retrospectively. There is no recorded information from police officers about which of the ST contacts prevented a S136 detention, with no information on diagnosis and on clinical outcomes available. Therefore, it is not possible to comment on whether people who would have previously ended up being detained under S136 received a different or improved outcome. There is also limited data on the economic impact of the intervention and requires further research.

Strengths

A strength of this study is that it uses data collected from three independent sources: the police, the NHS and a local authority. Routine data collected by the NHS on the use of S136 has often been limited to those assessments that occurred in hospitals and report only a limited set of outcomes. In this study, we have used two more reliable sources, namely raw data from the police and local authority. This allowed the triangulation of data to compare the impact of ST from different perspectives. Each data source indicated that ST had a dramatic impact on S136 detentions.

Another strength is that ST was implemented in two stages; this allowed a comparison of S136 rates of the localities where ST was operating to the ‘control’ localities which continued with treatment as usual for the first 10 months. A third strength is the detailed analysis of the use of other Mental Health Act sections in Sunderland. The data showed that ST did not significantly increase the use of other sections of the Mental Health Act in working age adults, and there was an association with a reduction in the use of Section 2.

Previous studies have not investigated the change in S136 in such detail and across such a large population. Recently, Heslin et al14 investigated ST in an area with a population of 0.1 million and found a 39% reduction over 6 months. We found a larger reduction (56%) in the first 12 months in a much larger area with a population of 1.4 million. Our study also has more detailed information of outcomes but less detail in terms of cost-effectiveness. Another recent study in a region adjacent to our study describes the ST service using qualitative approaches, but uses proxy data to describes its effectiveness.9

The rate of ST was higher than the rate of S136. Our results indicate that for every four ST interventions there was one fewer S136 detention. This is important as it suggests that ST is reaching a wider group than would previously have come into contact with mental health services via the police. Thus, it presents an opportunity to intervene early in this group of patient who are likely to have a number of different needs.

Implications

A surprising finding was that the outcomes of S136 detentions were not significantly different after ST implementation. It was anticipated that the introduction of ST would lead to a greater proportion of the S136 detentions resulting in further detention under the MHA. In Sunderland prior to ST, 15% of S136 detentions resulted in such further detention compared with a national figure of 17% in 2013/2014. After ST 19% of S136 resulted in further detention compared with a national figure of 16% in 2014/2015.15 The ST service in NTW does not operate between 03:00 and 10:00, and further investigation is required to ascertain whether there are systematic differences in the outcomes of these particular assessments that may explain this result. The pattern and outcome of S136 use may change as services progress with the understanding and operation of ST services, and if the operating hours are extended.

Our results indicate that the operation of ST across the whole of NTW resulted in 50 fewer S136 detentions per month or 600 per year. The Centre for Mental Health16 have estimated the cost of an arrest by the police at £1780. Local calculations lead to an estimated unit cost of £1632 across NHS, local authority, ambulance and police services for an average Section 136 detention lasting 3–4 hours. This is likely to be a conservative unit cost estimate as many detentions last far longer. Using these estimates, we calculate that ST generates annual savings of £1 million. If the reduction in Section 2 detentions is also replicated across other sites, then this would indicate further potential savings. Any savings would, of course, need to be set against the cost of running the service.

It is worth noting that A&E attendances with police did not increase to the same degree as all other A&E attendances in Sunderland. Some have argued that ST should seek to reduce A&E attendance. At the same time, A&E is sometimes used as a place for more detailed assessments to take place if a patient is willing to be seen. This raises important questions about what happens to individuals seen by ST in terms of subsequent contact with services. Further research is urgently required to evaluate the outcome of ST contacts and whether ST leads to improved patient outcomes and to delineate when ST is the best option and when S136 might be a preferred pathway.

ST brings the ability to respond speedily, with the combined skills and confidence of police officers working jointly with mental health professionals. In many cases, it is likely to be more appropriate and desirable to have an early mental health intervention before either removing someone to a ‘Place of Safety’ which may include police custody, although this remains an option when clinically indicated. Assessments in public places can raise issues of confidentiality which organisations should address through local policies. There will continue to be difficult scenarios beyond the scope of ST/S136 powers, such as when an individual is thought to be at risk on account of their mental disorder but is not in a public place.

Intriguingly, there was a reduction in voluntary admissions and Section 2 detentions in Sunderland, while the rate of detention under Section 3 remained unchanged. This is particularly worth noting as previously an association has been demonstrated between the reduction in bed numbers and an increase in detention rates.17. If these findings can be replicated in other areas, then this would suggest that ST has the potential to transform the delivery of adult mental health services. Future research should examine these positive results further, using a wider range of data, preferably prospective studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: PK jointly conceived the project, reviewed and oversaw protocol development the protocol, drafted and edited the manuscript. JF collected NHS data and performed analysis as well as reviewing and approving the content of the manuscript. GG collected Police data and contributed to information relating to the police in the manuscript. EN collected data from the Street Triage service and contributed to information related to this in the manuscript. SC collected data from the local authorities and contributed to local authority practices in the manuscript. PB contributed to the study protocol and provided information relating to the crisis service in the manuscript. JP developed the protocol and contributed to the development of the protocol. DL contributed to the study protocol and assisted in manuscript editing. IMK jointly conceived the project, reviewed and oversaw protocol development, drafted and edited the manuscript and prepared it for submission.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. They declare: PB is clinical director for Access and Treatment Services for Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust.

Ethics approval: This study obtained approval from Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development Department as part of a service evaluation of the NTW Street Triage Service. Caldicott approval was obtained from the NTW Caldicott Guardian on 17 June 2015.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Mental Health Act 1983 Code of Practice. London, UK: The Stationery Office, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health/Home Office. Review of the Operation of Sections 135 and 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales. A survey. London, UK: Department of Health/Home Office, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keown P. Place of safety orders in England: changes in use and outcome, 1984/5 to 2010/11. The Psychiatrist 2013;37:89–93. 10.1192/pb.bp.111.034348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MIND. Listening to experience—an independent inquiry into acute and crisis mental healthcare. London, UK: MIND, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.HMIC/CQC/Healthcare Inspectorate for Wales/HMIP. A criminal use of police cells? The use of police custody as a place of safety for people with mental health needs. London, UK: Crown copyright, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zisman S, O'Brien A. A retrospective cohort study describing six months of admissions under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act; the problem of alcohol misuse. Med Sci Law 2015;55:216–22. 10.1177/0025802414538247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HM Government. Mental Health Crisis Care Concordat Improving outcomes for people experiencing mental health crisis. London, UK: HM Government, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ralph M. The impact of crisis intervention team programs: fostering collaborative relationships. J Emerg Nurs 2010;36:60–2. 10.1016/j.jen.2009.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyer W, Steer M, Biddle P. Mental health street triage. Policing 2015;9:377–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molloy K. Report to Police and Crime Panel, 2015. http://tinyurl.com/jqxhky2 (accessed 27 Jan 2016).

- 11.Thames Valley Strategic Clinical Network. Street Triage, 2014. http://tinyurl.com/z3hck5a (accessed 27 Jan 2016).

- 12.Irvine AL, Allen L, Webber MP. Evaluation of the Scarborough, Whitby and Ryedale Street Triage Service. York, UK: Department for Social Policy and Social Work, University of York, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office for National Statistics. Census result shows increase in population of the North East. Office for National Statistics, 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/mro/news-release/census-result-shows-increase-in-population-of-the-north-east/censusnortheastnr0712.html (accessed 3 Feb 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heslin M, Callaghan L, Packwood M et al. Decision analytic model exploring the cost and cost-offset implications of street triage. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009670 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health & Social Care Information Centre. Inpatients formally detained in hospitals under the Mental Health Act 1983 and patients subject to Supervised Community Treatment, England—2013–2014, annual figures. Leeds, UK: Health & Social Care Information Centre, 2014. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB15812 (accessed 2 Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsonage M. Diversion: a better way for criminal justice and mental health. London, UK: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keown P, Weich S, Bhui KS et al. Association between provision of mental illness beds and rate of involuntary admissions in the NHS in England 1988–2008: ecological study. BMJ 2011;343:d3736 10.1136/bmj.d3736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011837supp_appendix.pdf (247.1KB, pdf)