Abstract

Background

The choice of cardiac resynchronization therapy device, with (CRT-D) or without (CRT-P) a defibrillator, in patients with heart failure largely depends on the physician׳s discretion, because it has not been established which subjects benefit most from a defibrillator.

Methods

We examined the annual trend of CRT device implantations between 2006 and 2014, and evaluated the factors related to the device selection (CRT-D or CRT-P) for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure by analyzing the Japan Cardiac Device Treatment Registry (JCDTR) database from January 2011 and August 2015 (CRT-D, n=2714; CRT-P, n=555).

Results

The proportion of CRT-D implantations for primary prevention among all the CRT-D recipients was more than 70% during the study period. The number of CRT-D implantations for primary prevention reached a maximum in 2011 and decreased gradually between 2011 and 2014, whereas CRT-P implantations increased year by year until 2011 and remained unchanged in recent years. Multivariate analysis identified age (odds ratio [OR] 0.92, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–0.95, P<0.0001), male sex (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.28–3.11, P<0.005), reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.98, P<0.0001), and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) (OR 2.85, 95% CI 1.87–4.35, P<0.0001) as independent factors favoring the choice of CRT-D.

Conclusions

Younger age, male sex, reduced LVEF, and a history of NSVT were independently associated with the choice of CRT-D for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure in Japan.

Keywords: Cardiac resynchronization therapy, Defibrillator, Primary prevention, Heart failure

1. Introduction

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is an effective option for the treatment of moderate to severe heart failure [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. The COMPANION trial [2] found that CRT with a defibrillator (CRT-D) was superior to that with a pacemaker (CRT-P) in terms of survival rate. However, direct comparisons of the efficacy of these devices are limited [2], [7], [8]. In fact, treatment with CRT-P also reduced all-cause mortality during a longer follow-up period [3]. In addition, the populations in these prospective studies consisted of patients with less advanced age (average 67 years) [2], [3], which may not always represent our daily medical practice.

The major role of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is to prevent sudden cardiac death due to ventricular tachycardia (VT) or fibrillation (VF). The MERIT-HF study reported that the incidence of sudden cardiac death in patients with NYHA class II–III was approximately 60%, whereas it was approximately 30% in patients with NYHA class IV [9]. A sub-analysis of the COMPANION trial concluded that CRT-P and CRT-D both had beneficial effects on mortality and morbidity in the severely ill population of NYHA class IV patients [10]. Moreover, the risk of sudden cardiac death decreased in association with aging, according to the Amiodarone Trialists MetAnalysis (ATMA) database of 6252 patients with structural heart disease [11]. The current guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology have proposed that the better candidates for CRT-D vs. CRT-P are patients with (1) stable heart failure, NYHA class II, (2) life expectancy more than 1 year, (3) ischemic heart disease, and (4) no comorbidities [12]. Therefore, the choice between CRT-D and CRT-P may largely depend on the physician׳s discretion, especially in patients without documented VT/VF who require CRT for primary prevention.

The present study aimed to examine national trends in the use of CRT devices and to determine factors affecting the choice of CRT-D in heart failure patients, based on data from the Japan Cardiac Device Treatment Registry (JCDTR) [13], [14], [15].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

The JCDTR was established in 2006 by the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society (JHRS) for a survey of actual conditions in patients undergoing implantation of cardiac implantable electronic devices (ICD/CRT-D/CRT-P) [13], [14], [15]. Members of the JHRS are encouraged to register their data under a unified protocol, which was normally approved by each facility. In Hokkaido University Hospital, the protocol was approved on September 20, 2012, by the Ethics Committee (approval number: 012-0156). As of January 30, 2016, 367 facilities in Japan have registered data voluntarily. The annual trend of implantation procedures was calculated from all the data until the end of 2014, except for 494 procedures with unknown devices. The comparative analyses between CRT-D and CRT-P for primary prevention were performed using records from the JCDTR database with an implantation date between January 2011 and August 2015 (Fig. 1). In addition, the JCDTR database from January 2006 to August 2010 (Supplemental Fig. 1) was also analyzed to determine whether there is a temporal trend regarding the choice of CRT devices.

Fig. 1.

Study population enrolled for the comparative analysis of CRT-D and CRT-P recipients for primary prevention during the period from January 2011 to August 2015. CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy (=biventricular pacing); CRT-D, CRT with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; CRT-P, CRT pacemaker.

2.2. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SD. Simple between-group analysis was conducted using Student׳s t-test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher׳s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the factors affecting the choice of CRT-D vs. CRT-P. Differences with P<0.05 were considered significant. Statview version 5.0 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Trends in the implantation procedures of CRT devices

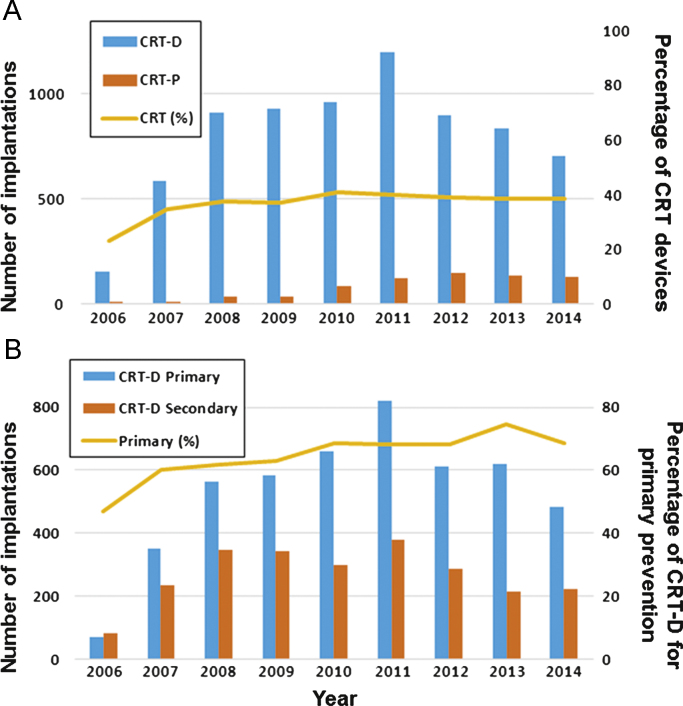

Implantation of CRT-P and CRT-D devices started in April, 2004 and August, 2006, respectively, in Japan. The annual totals of implantation procedures for CRT-D and CRT-P from the JCDTR database are given in Fig. 2A. Among all the procedures (including ICD), the percentage of CRT devices was constant at approximately 40% in recent years. The CRT-D implantation procedures were divided into those used for primary and secondary prevention (Fig. 2B). The number of CRT-D devices implanted for primary prevention reached a maximum in 2011 and decreased gradually between 2011 and 2014. In recent years, primary prevention accounted for approximately 70% of all CRT-D implantations. In contrast, the number of CRT-P implantations stayed almost constant between 2011 and 2014 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Annual distribution of cardiac implantable electronic device implantations between 2006 and 2014 from the JCDTR database. (A) Distribution of CRT-D and CRT-P implantations. The yellow line indicates the percentage of CRT devices (CRT-D and CRT-P) among all the devices (including ICD/CRT-D/CRT-P). (B) Distribution of CRT-P and CRT-D implantations for primary and secondary prevention. The yellow line indicates the percentage of primary prevention among all the CRT-D recipients. CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy (=biventricular pacing); CRT-D, CRT with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; CRT-P, CRT pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

3.2. Patient characteristics

The characteristics of patients receiving CRT-D (n=2714) and CRT-P (n=555) devices for primary prevention are shown in Table 1. Among 2714 CRT-D recipients, 2620 underwent initial implantation, whereas 35 and 59 patients were upgrades from CRT-P and ICD, respectively. Age, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), QRS duration, and QT interval were significantly lower in patients with CRT-D than in those with CRT-P. Male sex was prevalent in both groups, but its predominance was higher in patients with CRT-D. Patients receiving CRT-D were more likely to have a history of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). In contrast, they were less likely to have a history of persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) or hypertension. The percentage receiving a CRT device without an atrial lead was lower in CRT-D patients. The distributions of NYHA functional class and underlying heart diseases (ischemic vs. non-ischemic) were similar between the groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| CRT-D (n=2714) | CRT-P (n=555 ) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.5±10.9 | 74.7±10.9 | <0.0001 |

| Male sex | 2060 (75.9) | 341 (61.4) | <0.0001 |

| Underlying heart disease | 0.603 | ||

| Ischemic | 768 (28.3) | 150 (27.0) | |

| Non-ischemic | 1946 (71.7) | 405 (73.0) | |

| LVEF (%) | 27.4±9.3 | 32.5±11.2 | <0.0001 |

| LVEF≤35% | 2385 (87.9) | 392 (70.6) | <0.0001 |

| NYHA class | 0.151 | ||

| I | 52 (1.9) | 15 (2.7) | |

| II | 654 (24.1) | 125 (22.5) | |

| III | 1722 (63.4) | 370 (66.7) | |

| IV | 286 (10.5) | 45 (8.1) | |

| Heart rate (/min) | 70.6±16.9 | 69.6±18.0 | 0.171 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 154.7±30.1 | 161.2±29.3 | <0.0001 |

| <120 ms | 320 (11.8) | 35 (6.3) | |

| 120–149 ms | 790 (29.2) | 138 (25.0) | |

| ≥150 ms | 1595 (58.0) | 380 (68.7) | |

| QT interval (ms) | 456.7±53.7 | 468.1±54.6 | <0.0001 |

| Atrial lead | 0.0074 | ||

| Absent | 405 (14.9) | 108 (19.5) | |

| Present | 2309 (85.1) | 447 (80.5) | |

| NSVTa | 721 (69.7)a | 48 (41.7)a | <0.0001 |

| AF | 352 (13.0) | 81 (14.6) | 0.304 |

| Type of AF | 0.049 | ||

| Paroxysmal/persistent | 132 (38)/220 (62) | 21 (26)/60 (74) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 884 (32.6) | 187 (33.7) | 0.608 |

| Hypertension | 1132 (41.7) | 281 (50.6) | 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 880 (32.4) | 161 (29.0) | 0.116 |

| Hyperuricemia | 522 (19.2) | 95 (17.1) | 0.246 |

| Cerebral infarction | 183 (6.7) | 42 (7.6) | 0.484 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 91 (3.4) | 27 (4.9) | 0.082 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 710.8±1143.2 | 766.2±902.8 | 0.338 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7±2.0 | 12.1±1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.49±1.49 | 1.52±1.51 | 0.6226 |

Values are mean±SD, or number (%).

NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Information about the presence or absence of NSVT was available in 1034 CRT-D recipients and 115 CRT-P recipients.

Pharmacological therapy in patients receiving CRT-D or CRT-P is shown in Table 2. Use of β-blockers, class III antiarrhythmic drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, aldosterone antagonists, statins, and oral anticoagulant agents was significantly higher in patients receiving CRT-D. Ca2+ antagonists were prescribed in a lower percentage of patients with CRT-D.

Table 2.

Pharmacological therapy.

| CRT-D (n=2714) | CRT-P (n=555) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | 20 (0.74) | 5 (0.90) | 0.686 |

| Ib | 57 (2.10) | 11 (1.98) | 0.859 |

| Ic | 15 (0.55) | 4 (0.72) | 0.635 |

| β-Blockers | 2128 (78.4) | 352 (63.4) | <0.0001 |

| III | 871 (32.1) | 88 (15.9) | <0.0001 |

| Ca2+ antagonists | 226 (8.3) | 69 (12.4) | 0.0021 |

| Digitalis | 319 (11.8) | 62 (11.2) | 0.697 |

| Diuretics | 2106 (77.6) | 418 (75.3) | 0.243 |

| ACEI/ARB | 1813 (66.8) | 333 (60.0) | 0.0021 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 1152 (42.4) | 203 (36.6) | 0.011 |

| Nitrates | 232 (8.5) | 53 (9.6) | 0.446 |

| Statins | 810 (29.8) | 141 (25.4) | 0.036 |

| Oral anticoagulant agents | 1332 (49.1) | 246 (44.3) | 0.041 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 992 (36.6) | 193 (34.8) | 0.428 |

Data are given as number (%).

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers.

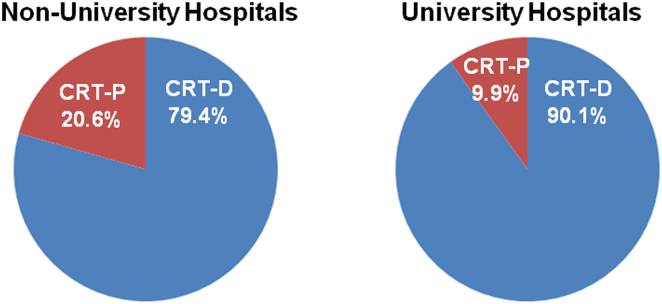

The type of hospital affected the choice of CRT-P. As expected, the proportion of CRT-P devices was higher in non-university hospitals compared to university hospitals (Fig. 3, P<0.0001). Conversely, the proportion of patients who had CRT-D for primary prevention was higher in university hospitals. On the other hand, β-blockers were given to 77.9% of CRT-D (n=1715) and 62.7% of CRT-P (n=445) recipients in non-university hospitals (P<0.0001), compared to 79.3% of CRT-D (n=999) and 66.4% of CRT-P (n=110) recipients in University hospitals. Thus, the use of β-blockers did not differ between non-university and university hospitals (P=0.400).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of CRT devices registered in the JCDTR by non-university (A) and university (B) hospitals. Among the study population (given in Fig. 1), 2160 patients and 1109 patients were enrolled from non-university hospitals and university hospitals, respectively. The proportion of CRT-P devices registered was 20.6% of patients from non-university hospitals and 9.9% of patients from university hospitals (P<0.0001). Conversely, the proportion of patients who had a CRT-D device for primary prevention was 79.4% in non-university hospitals and 90.1% in university hospitals.

3.3. Factors affecting the choice of CRT-D for primary prevention

To evaluate the independent variables associated with CRT-D (vs. CRT-P) implantation for primary prevention, logistic regression analysis, incorporating the demographic and comorbidity data given in Table 1, was performed for the study population between January 2011 and August 2015 (Fig. 1). In the multivariate analysis, age (odds ratio [OR] 0.92, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–0.95, P<0.0001), male sex (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.28–3.11, P<0.005), LVEF (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.98, P<0.0001), and the presence of NSVT (OR 2.85, 95% CI 1.87–4.35, P<0.0001) were significant factors favoring the choice of CRT-D.

Patient characteristics from the database between January 2006 and August 2010 are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Compared to those from the recent database (Table 1), apparent differences were observed in the age of those receiving CRT-P and a history of NSVT. The age increased from 71.8±11.7 to 74.7±10.9 (P=0.0080) in patients with CRT-P, whereas it did not change in those with CRT-D (67.1±11.3 vs. 67.5±10.9, P=0.257). The proportion of CRT-D patients with a history of NSVT decreased from 75.7% to 69.7% (P<0.0001).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined data from the JCDTR database that had been registered by the members of the JHRS from 2006 to 2014. We demonstrated that the number of CRT-D recipients for primary prevention decreased after 2011, whereas the CRT-P implants in recent years (i.e., between 2011 and 2014) remained almost constant and were more numerous than in the preceding years (i.e., between 2006 and 2010). In addition, we identified the following independent factors for the choice of CRT-D in recent years: younger age, male sex, lower LVEF, and a history of NSVT.

A subanalysis of the MADIT-CRT trial demonstrated that the factors associated with an LVEF improvement (LVEF>50%) by CRT were female sex, no previous myocardial infarction, left bundle branch block, baseline LVEF >30%, left ventricular end-systolic volume ≤170 mL, and left atrial volume index ≤45 mL/m2 [16]. The patients with LVEF improvement had a low risk of VT/VF (approximately 3% at 2 years) and a favorable clinical course within 2.2 years of follow-up. QRS duration ≥150 ms was also associated with a reduction in echocardiographic left ventricular end-diastolic volume in response to CRT-D [17]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that male sex and ischemic heart disease were significant moderator variables for a stronger benefit of CRT-D vs. CRT-P in primary prevention recipients [18]. Taken together, male patients with ischemic heart disease, lower LVEF, and less prolonged QRS are less likely to show a good response to CRT, thereby requiring ICD backup for primary prevention. In addition, detection of NSVT (at least 18 beats in duration and at least 188 beats/min) indicated a 4.3-fold increase in the risk of appropriate ICD shocks in the heart failure patients enrolled for SCD-HeFT [19]. Therefore, our tendency to select CRT-D would be reasonable in terms of the identified factors such as male sex, lower LVEF, and a history of NSVT. However, we should be cautious in the interpretation of our results, because the present study did not evaluate the patients’ outcomes.

A decreasing trend in CRT-D implantation has been reported recently, based on the database from the National Inpatient Sample in the USA [20]. They found that advancing age and an increasing comorbidity burden were associated with a reduced likelihood of CRT-D, and speculated that the decline in CRT-D implantation may reflect the intersection of high-comorbidity patients and the expectation of reduced ICD benefit in this patient population [20]. We found some differences in the patient characteristics between CRT-D and CRT-P (Table 1). These included age, sex, LVEF, QRS duration, QT interval, hemoglobin, and history of NSVT, hypertension, and persistent AF. However, when these patients’ background data in recent years were compared to previous years, a significant difference was observed only in age and prior NSVT. Therefore, the decrease in CRT-D and the increase in CRT-P implantation may be closely associated with the advancing age of the population in recent years.

The proportion of CRT-D implantations in primary prevention patients with a CRT device was 83% (2714 of 3269) in the present study. This was comparable to the 86% found in the USA [20], and was higher than the 69% reported in Europe (the CeRtiTuDe cohort study) [21]. Differences in the patients’ characteristics between CRT-D and CRT-P recipients were found by observational studies from Japan (JCDTR), Europe [21], and the USA [20]. For example, patients with AF were likely to receive CRT-P in Europe and the USA; however, this was not apparent in Japan. The etiology of the underlying heart diseases was one of the most striking differences. In Japan, the prevalence of ischemic heart disease was less than 30%, and it did not differ between the CRT-D and CRT-P population. In contrast, the ischemic etiology was 49.3% of CRT-D and 40.7% of CRT-P (CRT-D vs. CRT-P, P=0.003) in Europe [21], and 67.7% of CRT-D and 53.1% of CRT-P (CRT-D vs. CRT-P, P<0.001) in the USA [20]. Because there appear to be some modulator variables influencing the benefit of a defibrillator in CRT patients [18], differences in the choice of CRT devices and the patients’ backgrounds could affect the clinical outcome of heart failure patients requiring CRT. Further studies examining the prognosis of CRT patients are necessary to validate our choice among CRT devices in daily clinical practice in Japan.

4.1. Study limitations

This study had several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the data entries in the JCDTR are not always consecutive and have been registered on a voluntary basis. However, more than 367 facilities all over the country have contributed to the registry, which thereby represents the trends in Japan. Second, no information regarding QRS complex morphology was available in the JCDTR database. Third, the prevalence of AF was relatively low, despite the higher use of oral anticoagulants. This is probably related to the data entry system of the JCDTR, which does not require information regarding the presence or absence of AF in order to finish the registration. Fourth, patients’ body mass index, which could be a reason for selecting CRT-P, was not available from the JCDTR database.

5. Conclusions

CRT-D devices accounted for more than 80% of CRT implantations for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in Japan. However, the use of CRT-D has tended to decrease in recent years. The independent factors favoring the choice of CRT-D in heart failure patients without a history of sustained VT/VF were younger age, male sex, reduced LVEF, and prior NSVT, based on the analysis of the JCDTR database.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the JHRS who registered data in the JCDTR on a voluntary basis. As of January 30, 2016, 367 facilities in Japan had enrolled at least one patient. The list of the facilities that enrolled more than 100 patients (89 facilities in alphabetical order) is below.

Akita Medical Center, Anjo Kosei Hospital, Dokkyo Medical University, Edogawa Hospital, Fujita Health University, Fukushima Medical University, Gifu University, Gunma University, Hirosaki University, Hokkaido University Hospital, Hokko Memorial Hospital, Hyogo College of Medicine, IMS Katsushika Heart Center, Ishinomaki Red Cross Hospital, Itabashi Chuo Medical Center, Japanese Red Cross Society Kyoto Daini Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center, JCHO Hokkaido Hospital, JCHO Kyushu Hospital, Jichi Medical University, Juntendo University, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Kakogawa East City Hospital, Kameda Medical Center, Kanazawa Medical University, Keio University, Kitasato University, Kochi Health Science Center, Kokura Memorial Hospital, Komaki City Hospital, Kumamoto Red Cross Hospital, Kumamoto University, Kurashiki Chuo Hospital, Kyorin University, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto-Katsura Hospital, Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, Matsue Red Cross Hospital, Matsumoto Kyoritsu Hospital, Mito Saiseikai General Hospital, Nagasaki University, Nagoya University, National Hospital Organization Kagoshima Medical Center, National Hospital Organization Shizuoka Medical Center, Nihon University, Nippon Medical University, Odawara Municipal Hospital, Okayama University, Okinawa Prefectural Chubu Hospital, Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka City University, Osaka Medical College, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka University, Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital, Saiseikai Kumamoto Hospital, Saiseikai Shimonoseki General Hospital, Saiseikai Yokohamashi Tobu Hospital, Saitama Red Cross Hospital, Sakurabashi Watanabe Hospital, Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital, Sendai Kosei Hospital, Shiga University of Medical Science, Shinshu University, Shizuoka municipal Hospital, Showa General Hospital, St. Luke׳s International Hospital, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Takeda Hospital, Tenri Hospital, The University of Tokyo, Toho University, Tokai University, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo Metropolitan Hiroo Hospital, Tokyo Metropolitan Tama Medical Center, Tokyo Women׳s Medical University, Tottori University, Toyohashi Heart Center, Tsuchiura Kyodo General Hospital, University of Fukui, University of Miyazaki, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, University of Tsukuba, Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital, Yamagata University, Yamaguchi University, Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital, Yokohama Rosai Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http:dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joa.2016.04.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material Fig. 1. Study population enrolled for the comparative analysis of CRT-D and CRT-P recipients for primary prevention during the period from January 2006 to August 2010. CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy (=biventricular pacing); CRT-D, CRT with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; CRT-P, CRT pacemaker

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Abraham W.T., Fisher W.G., Smith A.L. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1845–1853. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bristow M.R., Saxon L.A., Boehmer J. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleland J.G., Daubert J.C., Erdmann E. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg I., Kutyifa V., Klein H.U. Survival with cardiac-resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1694–1701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss A.J., Hall W.J., Cannom D.S. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1329–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang A.S., Wells G.A., Talajic M. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold M.R., Daubert J.C., Abraham W.T. Implantable defibrillators improve survival in patients with mildly symptomatic heart failure receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis of the long-term follow-up of remodeling in systolic left ventricular dysfunction (REVERSE) Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:1163–1168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuchert A., Muto C., Maounis T. Lead complications, device infections, and clinical outcomes in the first year after implantation of cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy-pacemaker. Europace. 2013;15:71–76. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999;353:2001–7. [PubMed]

- 10.Lindenfeld J., Feldman A.M., Saxon L. Effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without a defibrillator on survival and hospitalizations in patients with New York Heart Association class IV heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115:204–212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.629261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krahn A.D., Connolly S.J., Roberts R.S. Diminishing proportional risk of sudden death with advancing age: implications for prevention of sudden death. Am Heart J. 2004;147:837–840. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brignole M., Auricchio A., Baron-Esquivias G. ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the Task Force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Eur Heart J. 2013;2013(34):2281–2329. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu A., Mitsuhashi T., Furushima H. Current status of cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillators and factors influencing its prognosis in Japan. J Arrhythm. 2013;29:168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu A., Nitta T., Kurita T. Current status of implantable defibrillator devices in patients with left ventricular dysfunction – the first report from the online registry database. J Arrhythm. 2008;24:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu A., Nitta T., Kurita T. Actual conditions of implantable defibrillator therapy over 5 years in Japan. J Arrhythm. 2012;28:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruwald M.H., Solomon S.D., Foster E. Left ventricular ejection fraction normalization in cardiac resynchronization therapy and risk of ventricular arrhythmias and clinical outcomes: results from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) trial. Circulation. 2014;130:2278–2286. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldenberg I., Moss A.J., Hall W.J. Predictors of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) Circulation. 2011;124:1527–1536. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barra S., Providência R., Tang A. Importance of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator back-up in cardiac resynchronization therapy recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015:4. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J., Johnson G., Hellkamp A.S. Rapid-rate nonsustained ventricular tachycardia found on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator interrogation: relationship to outcomes in the SCD-HeFT (Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2161–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindvall C., Chatterjee N.A., Chang Y. National trends in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circulation. 2016;133:273–281. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marijon E., Leclercq C., Narayanan K. Causes-of-death analysis of patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy: an analysis of the CeRtiTuDe cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2767–2776. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material Fig. 1. Study population enrolled for the comparative analysis of CRT-D and CRT-P recipients for primary prevention during the period from January 2006 to August 2010. CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy (=biventricular pacing); CRT-D, CRT with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; CRT-P, CRT pacemaker

Supplementary material