Abstract

Objectives

Atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) has multiple adverse effects on human health. Global atmospheric levels of PM2.5 increased by 0.55 μg/m3/year (2.1%/year) from 1998 through 2012. There is evidence of a causal relationship between atmospheric PM2.5 and breast cancer (BC) incidence, but few studies have investigated BC mortality and atmospheric PM2.5. We investigated BC mortality in relation to atmospheric PM2.5 levels among patients living in Varese Province, northern Italy.

Methods

We selected female BC cases, archived in the local population-based cancer registry, diagnosed at age 50–69 years, between 2003 and 2009. The geographic coordinates of each woman's place of residence were identified, and individual PM2.5 exposures were assessed from satellite data. Grade, stage, age at diagnosis, period of diagnosis and participation in BC screening were potential confounders. Kaplan-Meir and Nelson-Aalen methods were used to test for mortality differences in relation to PM2.5 quartiles. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards modelling estimated HRs and 95% CIs of BC death in relation to PM2.5 exposure.

Results

Of 2021 BC cases, 325 died during follow-up to 31 December 2013, 246 for BC. Risk of BC death was significantly higher for all three upper quartiles of PM2.5 exposure compared to the lowest, with HRs of death: 1.82 (95% CI 1.15 to 2.89), 1.73 (95% CI 1.12 to 2.67) and 1.72 (95% CI 1.08 to 2.75).

Conclusions

Our study indicates that the risk of BC mortality increases with PM2.5 exposure. Although additional research is required to confirm these findings, they are further evidence that PM2.5 exposure is harmful and indicate an urgent need to improve global air quality.

Keywords: particulate matter, environment, prognosis, survival, cancer registry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of few studies to address the relation between atmospheric PM2.5 and breast cancer (BC) mortality.

PM2.5 exposure was assessed using a new but validated method based on satellite data, overcoming the major limitation of measuring PM2.5 at thinly and irregularly distributed ground stations.

We used high-quality population-based cancer registry data to identify BC cases and assess patient mortality.

We controlled for confounding factors and also for participation in screening that may have introduced length-time and lead-time biases.

Limitations are that lifestyle factors and comorbidities were not considered and that exposure was assessed in the 10×10 km square containing the woman's residence, while time spent outside this square is unknown.

Introduction

Atmospheric particulate matter (PM) may be emitted or formed from natural or anthropogenic sources. In industrial and urban areas, PM is mainly anthropogenic.1 PM of diameter up to 10 μm (PM10) and fine PM, up to 2.5 μm (PM2.5), are documented to have multiple adverse effects on human health2 3 and are classified by the WHO and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as group 1 carcinogens (carcinogenic to humans).4

A recent prospective meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies from 9 European countries found a significant association between increasing levels of PM10 and PM2.5 and increasing lung cancer risk. The study concluded that PM air pollution contributed to lung cancer incidence in Europe.5

Notwithstanding the known toxicity of PM2.5, global population-weighted concentrations increased by 0.55 μg/m3/year (2.1%/year) from 1998 through 2012, largely driven by increases in developing countries such as China and India.6 It is noteworthy that the incidence of breast cancer (BC) is also increasing worldwide, and it is now the most common female cancer worldwide.7 In 2012, an estimated 1.67 million new cases were diagnosed across the globe: 749 000 in developed countries and 883 000 in developing countries.7

Reasonable hypotheses are that the global increase in BC incidence might be linked to increasing in PM concentrations and that high PM might also worsen BC survival. This is supported by the findings of a population-based study in California,8 which found that exposure to higher PM10 (HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.25, per 10 μg/m3) and PM2.5 (HR 1.86, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.10, per 5 μg/m3) was significantly associated with early mortality among women with BC after adjusting for numerous covariates.

There are other reasons to suspect an association between BC survival and PM levels in the atmosphere. A Canadian study that assessed NO2 levels as a proxy of traffic-related air pollution found that BC incidence increased with increasing NO2 exposure.9 A Japanese study found that PM2.5 levels estimated from measured PM10 levels were significantly associated with mortality for breast, endometrial and ovarian cancers after adjusting for smoking, population density and hormone-related factors.10 A 2007 cohort study in Western New York State also found that high exposure to traffic emissions at the time of menarche was associated with increased risk of premenopausal BC (OR 2.05, 95% CI 0.92 to 4.54, p trend 0.03); and that high exposure at time of first birth increased the risk of postmenopausal disease (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.16 to 5.69, p trend 0.19).11

To further probe the association of atmospheric PM with BC, we carried out the present study in Varese Province, northern Italy. We investigated BC mortality (primary study end point) in relation to residential exposure to atmospheric PM2.5 as determined by a satellite-based method.

Materials and methods

Study area

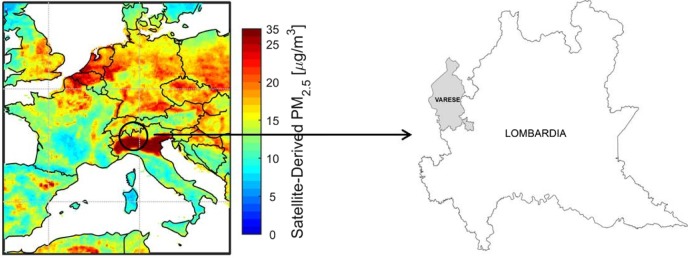

Varese Province, Region of Lombardy, northern Italy (figure 1) has a population of 877 000 and a population density of 731.4/km2. PM2.5 comes mainly from non-industrial emissions (eg, heating) (30–42%) and road traffic (30–32%).12 As figure 1 shows, Varese Province is situated in an area (the plain of the river Po) enclosed by mountains which block atmospheric circulation. As a result, atmospheric pollution tends to build-up. In fact, atmospheric PM2.5 levels in the plain of the Po are among the highest in the world.6

Figure 1.

Map of the study area and satellite-derived PM2.5. PM, particulate matter.

Varese Province is also characterised by high BC incidence (world age standardised rate 89.3/100 000)7 and a high quality cancer registry that is likely to have registered essentially all BC cases occurring over any relatively recent period.13 14

Breast cancer cases

We performed a retrospective study on a cohort of women diagnosed with primary BC. The cases were archived by the Varese section of the Lombardy Cancer Registry. A search using site code C50 and malignant epithelial morphology codes M8010–M8575 of the International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICDO-3) retrieved a total of 2021 primary BC cases diagnosed in the predetermined study period (2003–2009) and conforming to our selection criteria (50–69 years at diagnosis, no other cancer diagnosed previously).15 All 2021 BC cases were used in the analysis. Disease stage was as specified by the TNM classification of malignant tumours (6th edition, 2002).16

Mortality ascertainment

Mortality data from the Varese Province mortality database are routinely collected by the cancer registry and linked to cancer cases by the Epilink software, which achieved 98.8% specificity and 96.5% sensitivity for linking in a published study.17 Epilink flags problematic cases for manual checking to enhance linkage accuracy. Each cancer case identified as deceased is checked against the Social Security List of all persons who receive health caser in the Region of Lombardy (essentially the entire population). The vital status field for each person in the Social Security List is updated frequently and serves as an independent check of the vital status of cancer cases archived by the registry.

Estimation of PM2.5

The procedure for estimating PM2.5 exposure involved first retrieving each patient's address at the date of diagnosis (reference date) from the cancer registry and then determining the geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) of each address using the ArcGis V.10.0 software.18 Ground level PM2.5 exposure at each address was then estimated from satellite observations. The actual PM2.5 value used as exposure proxy was the median of ground level PM2.5 concentrations over the 3 years around the diagnosis date (so as to reduce noise in the annual satellite-derived values). Thus if a woman was diagnosed in 2006, the PM2.5 concentration used was the median of annual concentrations for the years 2005, 2006 and 2007. The method described by van Donkelaar et al6 was used to estimate ground level PM2.5 exposure. This approach combined daily total column aerosol optical depth data from the NASA Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), Multiangle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR) and Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor (SeaWIFS) satellite instruments, with coincident vertical aerosol profile and scattering properties estimated by the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model, so as to produce longer term means.6 Total column aerosol optical depth is a measure of the total light extinction due to scattering and absorption by atmospheric aerosols.

The ground level PM2.5 estimates were available at a resolution of 10×10 km, and BC case exposure was estimated as median PM2.5 concentration over 3 years in the 10×10 km area containing each case's residence. Exposure variations arising from daily or periodic movements away from home are not considered by this method.

Data produced by this method have been shown to correlate well with levels determined by ground-based PM2.5 detectors6 and have the advantage that they are available over an entire territory, while ground-based observation stations are generally few and irregularly spaced. In Varese Province, only four ground-based sites measure PM2.5.

Statistical methods

The analyses we performed are based on the Cox proportional hazard model which specifies the hazard as λ(t)=λ0(t)exp (βX), where λ(t) is the hazard function for the event in question (death). X is a vector of covariates, and β is a vector of coefficients to be estimated. The hazards for two participants with fixed covariate vectors Xi and Xj are λi (t)=λ0(t)exp(βXi) and λj (t)=λ0(t)exp(βXj), respectively. The HR is λi(t)/λj(t)=exp (β(Xi−Xj)). To test the null hypothesis H0 that β=0, we used the likelihood ratio test. Since the Cox model assumes proportional hazards, this was tested by analysis of scaled Schoenfeld residuals, with associated p values. When the hazard was suspected to be non-proportional over time, we performed additional analyses, substituting the conventional Cox β coefficient (for a given variable) with a time-dependent function β(t) obtained by adding the smoothed scaled Schoenfeld residuals to the conventional β coefficient.19–21

Factors known or thought to influence BC prognosis were initially analysed by univariate Cox proportional hazard modelling to verify their effect on BC mortality in our cohort. Factors analysed were diagnosis period (2003–2006; 2007–2009), stage (I–IV), grade (I–III, unknown), age at diagnosis (two categories, 50–59 years and 60–69 years) and participation in a BC screening programme (yes, no). Year of diagnosis was included since, over time, treatment may have improved, and diagnosis may have occurred earlier. Cancers diagnosed in the screening context are affected by length-time and lead-time bias and may also be less aggressive than those diagnosed outside of screening.22

We next ran univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models to estimate HRs with 95% CIs of BC death according to quartiles of PM2.5 exposure. The multivariate model was stratified (separate baseline hazard functions for each variable category within the model) by age, grade, stage, diagnosis period and participation in screening to control for the possible confounding effects of these variables on mortality.

Time to event or end of follow-up was calculated from date of diagnosis. Cases that died of causes other than breast cancer were censored at the date of death. Patients alive at the study end were censored at that time (31 December 2013). Patients lost to follow-up were censored at the date of loss to follow-up. Cases with missing data (missing disease stage and tumour grade) were assigned to ‘not specified’ categories in the analyses.

We also used the Kaplan-Meier method to produce survival curves for quartiles of PM2.5 exposure, testing the significance of differences between curves with the stratified log-rank test. We also used the Nelson-Aalen estimator to plot the cumulative hazard of BC death for PM2.5 exposure categories. The analyses were performed using the R statistical package (R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2007. http://www.r-project.org).

Italian legislation identifies cancer registries as collectors of personal data for research and public health purposes and does not consider that specific approval by an ethics committee is required to use these data for research and public health purposes. Although our study was an observational one based on individual data, all such data were anonymised prior to analysis.

Results

Disease and other characteristics of the 2021 patients with BC are shown in table 1. A total of 101 (5%) women changed address during the study period: 90 of these moved from one part of the Province to another (and may have changed PM2.5 exposure), while 11 moved outside the study area and were censored at the date of leaving. A total of 325 (16.1%) women died in the period up to 31 December 2013, 246 (12.2%) of these of BC. Table 1 also shows HRs for BC death according to categories of prognostic variables: HR of death increased significantly with advancing stage and grade, while participation in screening was associated with considerably reduced risk of death, at least over the study period. These findings are as expected.

Table 1.

Patient (n=2021) and disease characteristics with univariate HRs and 95% CIs for breast cancer death

| Variable | Breast cancer cases (N) | Breast cancer deaths (N) | HR (95% CI) for breast cancer death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period of diagnosis | |||

| 2003–2006 | 1199 | 163 | 1 |

| 2007–2009 | 822 | 83 | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) |

| Disease stage | |||

| I | 887 | 25 | 1 |

| II | 550 | 48 | 3.21 (1.98 to 5.21) |

| III | 292 | 93 | 13.31 (8.56 to 20.70) |

| IV | 35 | 27 | 75.94 (43.94 to 131.24) |

| Not specified | 257 | 53 | 8.26 (5.14 to 13.3) |

| Participation in screening | |||

| No | 1341 | 213 | 1 |

| Yes | 680 | 33 | 0.29 (0.20 to 0.41) |

| Tumour grade | |||

| I | 193 | 3 | 1 |

| II | 1132 | 97 | 5.43 (1.72 to 17.13) |

| III | 513 | 104 | 14.06 (4.46 to 44.33) |

| Not specified | 183 | 42 | 16.93 (5.25 to 54.63) |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| 50–59 | 923 | 110 | 1 |

| 60–69 | 1098 | 136 | 1.05 (0.82 to 1.35) |

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate and multivariate analyses, presented as HRs with 95% CIs for BC death according to quartiles of PM2.5 exposure. By the univariate model, patients with BC living in an area with PM2.5 levels above the lowest quartile had significantly greater risk of BC death than those living in areas with lowest quartile of PM2.5 (<21.10 μg/m3). The increased risk of death ranged from 72% (fourth quartile) to 82% (second quartile). For the multivariate model, which controlled for confounding factors, the likelihood ratio test gave p=0.029, indicating that the null hypothesis of no association between BC mortality and PM2.5 could be rejected. In detail, HRs of BC death were numerically greater than those produced by the univariate analyses and significant for all exposure quartiles above the lowest.

Table 2.

HRs and 95% CIs for breast cancer death in relation to PM2.5 exposure

| Cases (N) | Deaths (N) | HR (95% CI), breast cancer death |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 quartiles (μg/m3) | Univariate | Multivariate* | ||

| I (<21.10) | 504 | 40 | 1 | 1 |

| II (21.10–24.20) | 462 | 56 | 1.56 (1.04 to 2.34) | 1.82 (1.15 to 2.89) |

| III (24.20–26.50) | 530 | 71 | 1.55 (1.06 to 2.29) | 1.73 (1.12 to 2.67) |

| IV (≥26.50) | 525 | 79 | 1.49 (1.02 to 2.19) | 1.72 (1.08 to 2.75) |

*Multivariate stratified by age, stage, grade, diagnosis and participation in screening.

PM, particulate matter.

Analysis of scaled Schoenfeld residuals showed that p values for increasing PM2.5 quartiles were 0.93, 0.40, 0.38 and 0.32, indicating that the null hypothesis of no variation of hazard with time could not be rejected, suggesting that the prognostic effect PM2.5 remained constant over the entire follow-up.

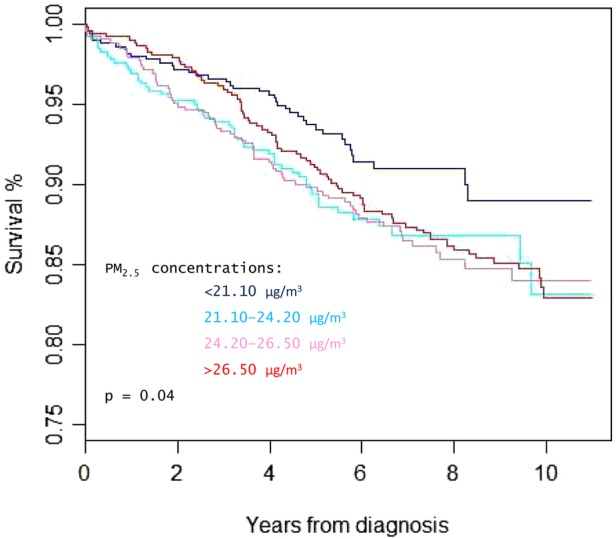

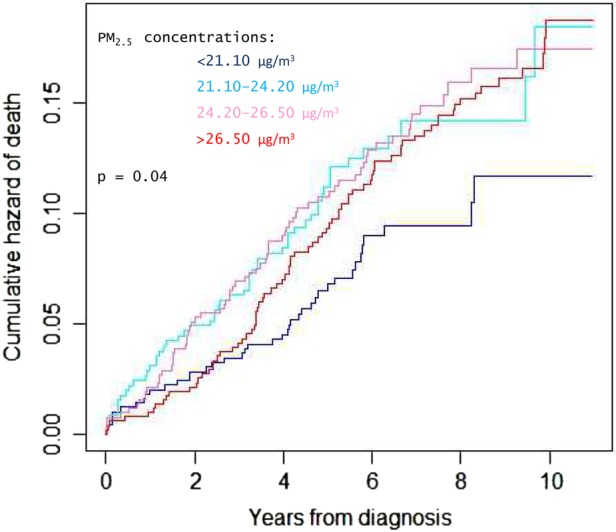

Figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meir survival curves by PM2.5 quartiles. Figure 2 shows Nelson-Aalen estimates of the cumulative hazard of BC death by PM2.5 quartiles. Figures 2 and 3 indicate that patients with BC exposed to the three upper PM2.5 levels (≥21 100 μg/m3) had a significantly (p=0.04, stratified log-rank test) greater risk of BC death than those living in an area with the lowest quartile of PM2.5.

Figure 2.

Survival of breast cancer cases, diagnosed in 2003–2009 and resident in Varese Province, northern Italy according to exposure to PM2.5 (quartiles). PM, particulate matter.

Figure 3.

Cumulative hazard of breast cancer death in cases diagnosed in 2003–2009 and resident in Varese Province, according to exposure to PM2.5 (quartiles). PM, particulate matter.

Yearly (2003–2009) averages of PM2.5 exposure for all study women were as follows: 26.57, 26.65, 26.43, 23.73, 21.78, 21.44 and 20.71 μg/006D3.

Discussion

We have shown that high exposure to PM2.5 is associated with increased mortality for BC after correcting for a range of factors considered to influence BC survival. As regard to possible mechanisms mediating this association, little evidence is available. A recent study collected airborne particles in Taiwan and investigated their effects on BC cell lines.23 The particles themselves and their solvent extracts had a variety of effects on the cell lines, including in particular increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), increased numbers of DNA strand breaks and estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity (concentration dependent). It is noteworthy that particle-induced ROS generation was blocked by treatment with aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonist, suggesting that the aryl hydrocarbon receptor mediated the particle-induced toxicity. This is consistent with the positive association between exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from car traffic and BC incidence, reported by the Long Island Breast Cancer Study.24 The authors of the Taiwan study concluded that particle-induced ROS formation contributed to oxidative DNA damage that may mediate particle-induced carcinogenesis.23

The finding that particles have oestrogenic and DNA-damaging effects suggests a potential mechanism for an effect on BC: if inhaled PM entered the circulatory system from the lungs, oestrogenic particles might find their way to breast tissue. However to the best of our knowledge no data are available to indicate whether PM can reach breast tissue, and further research is required in this area.25 Most of the toxic effects of PM have been attributed either to direct damage to lung tissue or release of inflammatory mediators from airway cells into the circulatory system.26 Notwithstanding these considerations, the biological mechanisms by which PM2.5 exposure increases to BC mortality remain unknown.

Our study has several strengths. We used a population-based cancer registry to identify virtually all the BC cases in the study area over the study period, in turn linking them to mortality databases to obtain accurate and complete survival information. Another strength is our use of satellite-derived PM2.5. Traditional ground-based PM measurement methods are locally accurate, but are sparsely and irregularly distributed, adding considerable uncertainty to individual exposure assignments over a wide geographic area. The satellite data made it possible to estimate the exposure in each 10×10 km area containing each woman's home. We consider that this area is particularly apt for our purposes as it comprises the area where the woman is likely to have carried out most of her daily activities. Of course some women may have spent a considerable fraction of their time outside this area, perhaps at work, and this is a study weakness. Importantly, none of the women had missing values for PM2.5 exposure.

Another study strength is that we controlled for factors (eg, stage, grade and participation in screening) known or suspected to influence BC mortality. However, we did not control for lifestyle factors, including diet and alcohol consumption, or comorbidities, that may also influence BC mortality.27–29

The Californian study—the only other published study on BC mortality in relation to PM2.5 exposure—also found a strong association between BC mortality and PM2.5 exposure. However, PM2.5 exposure for people living in California was much lower than in Varese Province, which is among the highest in the world.6 The lowest exposure category for California was PM2.5 <11.64 μg/m3: only three patients in our data set had such a low exposure. However, the California researchers reported an HR for the upper category of 1.76 that is similar to the HRs for our three upper categories (1.82, 1.73 and 1.72, respectively).

A report of ongoing research in northern China on the link between PM10 and BC survival also indicated increased risk with increasing PM exposure and also that survival was lower in women with oestrogen receptor positive disease.30 The authors suggested that PM may act as a xenoestrogen, in line with the data from the study on effects of PM on BC cell lines.23

It is important to emphasise that the first quartile of exposure in our study is not a risk zero category, but only the reference category for the other quartiles.

In conclusion, although our study has limitations, its findings are consistent with those of the California study and the report of a study in China indicating a strong association between BC death and atmospheric PM exposure. Clearly, more research is justified to further explore this association, particularly in view of the increasing worldwide incidence of BC and worldwide increases in PM concentrations.6 7 Our data add to the wealth of evidence that atmospheric PM has multiple adverse effects on human health and indicate an urgent need to lower atmospheric PM levels worldwide.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Don Ward for help with the English and for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: PC contributed to study conception, designed the study, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. GT contributed to study conception, coordinated the clinical section of the study and contributed to writing the paper. RT and GB contributed to practical aspects of study design. AB, MB and AT were responsible for the exposure assessment. AvD and RVM were responsible for developing the model deriving PM data from satellite data. AT, SF, AS and GB developed the information system to archive and manage the data and performed the descriptive statistics. AM and TC retrieved the clinical information and performed the record linkage between the sources. IF and AC transferred the clinical data into the study database. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. IARC Scientific Publication no. 161: Air pollution and cancer. http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/books/sp161/AirPollutionandCancer161.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.Barman SC, Kumar N, Singh R et al. . Assessment of urban air pollution and it's probable health impact. J Environ Biol 2010;31:913–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fantke P, Jolliet O, Evans JS et al. . Health effects of fine particulate matter in life cycle impact assessment: findings from the Basel Guidance Workshop. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2015;20:276–88. 10.1007/s11367-014-0822-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. IARC monographs: volume 109: outdoor air pollution. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol109/mono109.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen ZJ, Beelen R et al. . Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: prospective analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Lancet Oncol 2013;14:813–22. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70279-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, Brauer M et al. . Use of satellite observations for long-term exposure assessment of global concentrations of fine particulate matter. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:135–43. 10.1289/ehp.1408646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. IARC: GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx.

- 8.Hu H, Dailey AB, Kan H et al. . The effect of atmospheric particulate matter on survival of breast cancer among US females. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;139:217–26. 10.1007/s10549-013-2527-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hystad P, Villeneuve PJ, Goldberg MS et al. , Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution and the risk of developing breast cancer among women in eight Canadian provinces: a case–control study. Environ Int 2015;74:240–8. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwai K, Mizuno S, Miyasaka Y et al. . Correlation between suspended particles in the environmental air and causes of disease among inhabitants: cross-sectional studies using the vital statistics and air pollution data in Japan. Environ Res 2005;99:106–17. 10.1016/j.envres.2004.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nie J, Beyea J, Bonner MR et al. . Exposure to traffic emissions throughout life and risk of breast cancer: the Western New York Exposures and Breast Cancer (WEB) study. Cancer Causes Control 2007;18:947–55. 10.1007/s10552-007-9036-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. http://www.inemar.eu/xwiki/bin/view/Inemar/

- 13.Tagliabue G, Maghini A, Fabiano S et al. . Consistency and accuracy of diagnostic cancer codes generated by automated registration: comparison with manual registration. Popul Health Metr 2006;4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contiero P, Tittarelli A, Maghini A et al. . Comparison with manual registration reveals satisfactory completeness and efficiency of a computerized cancer registration system. J Biomed Inform 2008;41:24–32. 10.1016/j.jbi.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. International classification of diseases for oncology, Third Edition, First Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobin LH, Wittekind C. International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM classification of malignant tumors. 6th edn New York: Wiley-Liss, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contiero P, Tittarelli A, Tagliabue G et al. . The EpiLink record linkage software: presentation and results of linkage test on cancer registry files. Methods Inf Med 2005;44:66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. ESRI: ArcGIS. http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis.

- 19.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Testing proportional hazards. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York: Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellera CA, MacGrogan G, Debled M et al. . Variables with time-varying effects and the Cox model: some statistical concepts illustrated with a prognostic factor study in breast cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:20 10.1186/1471-2288-10-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrell F. Regression modeling strategies. Springer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry DA. Failure of researchers, reviewers, editors, and the media to understand flaws in cancer screening studies: application to an article in Cancer. Cancer 2014;120:2784–91. 10.1002/cncr.28795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen ST, Lin CC, Liu YS et al. . Airborne particulate collected from central Taiwan induces DNA strand breaks, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation, and estrogen-disrupting activity in human breast carcinoma cell lines. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng 2013;48:173–81. 10.1080/10934529.2012.717809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mordukhovich I, Beyea J, Herring AH et al. . Vehicular traffic-related polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and breast cancer incidence: the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project (LIBCSP). Environ Health Perspect 2015. 10.1289/ehp.1307736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutton P, Kavanaugh-Lynch MH, Plumb M et al. . California breast cancer prevention initiatives: setting a research agenda for prevention. Reprod Toxicol 2015;54:11–18. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rundell KW. Effect of air pollution on athlete health and performance. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:407–12. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romieu I, Scoccianti C, Chajès V et al. . Alcohol intake and breast cancer in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int J Cancer 2015;137:1921–30. 10.1002/ijc.29469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenzie F, Ferrari P, Freisling H et al. . Healthy lifestyle and risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort Study. Int J Cancer 2015;136:2640–8. 10.1002/ijc.29315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Søgaard M, Thomsen RW, Bossen KS et al. . The impact of comorbidity on cancer survival: a review. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:3–29. 10.2147/CLEP.S47150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huo Q, Cai C, Yang Q. Atmospheric particulate matter and breast cancer survival: estrogen receptor triggered? Tumour Biol 2015;36:3191–3. 10.1007/s13277-015-3291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]