Abstract

Background

Historically, women have lower all-cause mortality than men. It is less understood that sex differences have been converging, particularly among certain subgroups and causes. This has implications for public health and health system planning. Our objective was to analyse contemporary sex differences over a 20-year period.

Methods

We analysed data from a population-based death registry, the Ontario Registrar's General Death file, which includes all deaths recorded in Canada's most populous province, from 1992 to 2012 (N=1 710 080 deaths). We calculated absolute and relative mortality sex differences for all-cause and cause-specific mortality, age-adjusted and age-specific, including the following causes: circulatory, cancers, respiratory and injuries. We used negative-binomial regression of mortality on socioeconomic status with direct age adjustment for the overall population.

Results

In the 20-year period, age-adjusted mortality dropped 39.2% and 29.8%, respectively, among men and women. The age-adjusted male-to-female mortality ratio dropped 41.4%, falling from 1.47 to 1.28. From 2000 onwards, all-cause mortality rates of high-income men were lower than those seen among low-income women. Relative mortality declines were greater among men than women for cancer, respiratory and injury-related deaths. The absolute decline in circulatory deaths was greater among men, although relative deciles were similar to women. The largest absolute mortality gains were seen among men over the age of 85 years.

Conclusions

The large decline in mortality sex ratios in a Canadian province with universal healthcare over two decades signals an important population shift. These narrowing trends varied according to cause of death and age. In addition, persistent social inequalities in mortality exist and differentially affect men and women. The observed change in sex ratios has implications for healthcare and social systems.

Keywords: Mortality, Sex, Socioeconomic status

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study includes all deaths (over 1.7 million) recorded in Canada's most populous province over a 20-year period.

The data represent a true population-based picture of mortality trends in the context of a universal healthcare system and cover 20 years, allowing for stable observations regarding persistent trends.

Absolute and relative sex-specific mortality trends were analysed by cause, age and socioeconomic status (SES) to measure the extent to which sex convergence has been taking place.

Ecological measures of SES were used as individual measures were not available.

These data do not contain information on race/ethnicity and thus do not reflect whether sex-specific trends differentially affected certain racial/ethnic groups over time.

Introduction

Historically, all-cause and sex-specific mortality rates have been higher among men compared to women.1–5 There have been several explanations proposed for higher mortality rates among men. These range from biological reasons, such as hormonal or intrauterine factors, differential healthcare usage6 as well as social and behavioural differences, such as alcohol consumption and smoking patterns.7 While these sex-specific differences appeared to be growing during the first part of the last century,8 contemporary analyses of these ratios have suggested that the male-to-female mortality gap may be narrowing in certain countries, although not universally.9 10

Certain causes of death have shown more pronounced sex ratios compared to others, such as cardiovascular disease; however, there is limited evidence examining these ratios across several conditions to demonstrate specifically for which causes of death sex-specific convergences are occurring. Understanding this phenomenon has significant implications given the predominant view that men are seemingly inherently disadvantaged towards having higher mortality rates compared to women. Examples are possible influences on clinical decision-making public health and prevention efforts targeting risk factor reductions or addressing social inequities in health. As such, it is important to examine sex-specific mortality differences over a recent, sizeable time period and across several causes and subgroups, to determine the nature of these changes in sex-specific mortality trends.

Our objective was to analyse trends in sex-specific mortality differences in the 20 years spanning 1992 to 2012 using a large population-based sample to first quantify the narrowing sex-gap and second to examine specific convergence trends according to time, age and causes of death. In addition, we sought to analyse these trends according to socioeconomic status (SES) to investigate potential inequities in sex-specific mortality declines experienced over two decades.

Methods

Data source

We analysed all deaths that occurred in the province of Ontario, Canada's largest province with a population of ∼13 million residents. Deaths were identified using the Ontario Registrar General's Death file (ORG-D), a population-based mortality database which captures all deaths occurring in residents, of all ages, from the province of Ontario. ORG-D, the Ontario version of the Canadian Mortality Database, codes causes of death according to the Word Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Revision.11 Note that for deaths occurring after 2000, when ICD-10 was introduced, validated national conversion tables were used to ensure consistent cause of death coding over the study period.12 ORG-D contains data on ∼1.9 million Ontario deaths occurring since 1 January 1990. Recently, ORG-D has been linked to Ontario's population registry (the Registered Persons Database, RPDB), which was established 1 April 1990; thereby, allowing for verification of death records and resulting in a high quality, population-based mortality registry. Furthermore, the RPDB contains sex and age information, which was used to derive sex ratios and make age adjustments. From 1992 onwards, this linkage rate has exceeded 97%; therefore, we used mortality records from 1992 to the most recent year for which data were available (2012), resulting in a full 21 calendar years of population-based mortality data for this analysis. Finally, this linkage enabled use of individual-level postal code information to assign neighbourhood-level income quintile values according to the nearest-date Statistics Canada census; the smallest geographic area, referred to as a dissemination area, was used for this purpose.13 Full details on the ICD codes used for this analysis are provided in online supplementary table S1. These databases are made available to accredited researchers through a data sharing agreement with the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. These individual-level data are linked using a coded identification number in accordance with the provincial Personal Health Information Protection Act.

bmjopen-2016-012564supp.pdf (274.7KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

We calculated crude and age-adjusted mortality rates according to the number of all-cause and cause-specific deaths for four common causes of mortality: diseases of the circulatory system, cancers, diseases of the respiratory system and injury (see online supplementary table S1). Further, we calculated age-specific mortality rates for the following age groups: <35, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84 and 85+; summary measures of overall 20-year age-specific relative and absolute differences were additionally calculated. We directly age-adjusted mortality rates using a negative binomial regression model separately for men and women using the pseudo-least-squared means methods. Male-to-female sex mortality ratios were calculated by dividing the male-specific adjusted mortality rate by the female-specific rate per year. A sex mortality ratio >1 indicates that male mortality exceeds female mortality; whereas, a sex mortality ratio <1 indicates that female mortality exceeds that of men and a sex mortality ratio =1e indicates no sex difference. Given the relative nature of these measures, we plotted the natural logarithm of this ratio. In addition to relative differences between men and women, we calculated absolute sex differences by taking the difference between male and female mortality rates each year. We also examined trends across neighbourhood-level income quintiles to examine sex-specific changes according to SES. We assessed model fit according to AIC criterion, overdispersion and observed versus predicted mortality. All analyses used sex-specific population counts from the RPDB as denominators. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Our analysis included 1 710 080 deaths, occurring between 1992 and 2012 in the province of Ontario. During these 20 years, age-adjusted and age-standardised annual mortality rates decreased substantially for both sexes (figure 1). In 1992, age-adjusted mortality rates were almost 50% higher among men compared to women; by 2012, mortality rates fell by 39.2% among men and 29.8% among women. Compared to a ratio of 1.0 (sex equivalence), the age-adjusted male-to-female mortality ratio declined by 41.4%; falling from 1.47 to 1.28 over the 20 years. The age-adjusted absolute differences similarly declined from 2.35 to 0.97 per 1000 persons; representing a 58.9% decline (table 1).

Figure 1.

All-cause age-standardised mortality from 1992 to 2012. All rates are standardised to the 1991 Canadian population.

Table 1.

Age-adjusted all-cause mortality rates per 1000 persons and differences by year (1992–2012)

| Age-adjusted* rates (95% CI) |

Male − female differences |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Males | Females | Absolute (males − females) | Ratio (males:females) |

| 1992 | 7.310 (7.032 to 7.599) | 4.958 (4.863 to 5.054) | 2.352 | 1.474 |

| 1993 | 7.246 (6.971 to 7.532) | 5.033 (4.938 to 5.13) | 2.213 | 1.440 |

| 1994 | 7.097 (6.827 to 7.377) | 4.995 (4.901 to 5.091) | 2.101 | 1.421 |

| 1995 | 6.863 (6.602 to 7.134) | 4.938 (4.845 to 5.032) | 1.925 | 1.390 |

| 1996 | 6.603 (6.352 to 6.863) | 4.846 (4.755 to 4.939) | 1.757 | 1.362 |

| 1997 | 6.392 (6.149 to 6.645) | 4.735 (4.646 to 4.825) | 1.657 | 1.350 |

| 1998 | 6.133 (5.900 to 6.376) | 4.661 (4.574 to 4.75) | 1.472 | 1.316 |

| 1999 | 5.974 (5.747 to 6.210) | 4.602 (4.516 to 4.689) | 1.372 | 1.298 |

| 2000 | 5.779 (5.559 to 6.007) | 4.464 (4.381 to 4.549) | 1.315 | 1.295 |

| 2001 | 5.586 (5.374 to 5.806) | 4.354 (4.273 to 4.437) | 1.232 | 1.283 |

| 2002 | 5.390 (5.185 to 5.602) | 4.271 (4.192 to 4.352) | 1.118 | 1.262 |

| 2003 | 5.408 (5.204 to 5.620) | 4.207 (4.130 to 4.287) | 1.201 | 1.285 |

| 2004 | 5.167 (4.972 to 5.370) | 4.033 (3.958 to 4.109) | 1.134 | 1.281 |

| 2005 | 5.054 (4.863 to 5.251) | 4.058 (3.984 to 4.134) | 0.995 | 1.245 |

| 2006 | 4.898 (4.714 to 5.090) | 3.852 (3.781 to 3.924) | 1.046 | 1.272 |

| 2007 | 4.930 (4.745 to 5.121) | 3.849 (3.779 to 3.921) | 1.080 | 1.281 |

| 2008 | 4.867 (4.682 to 5.060) | 3.866 (3.795 to 3.939) | 1.001 | 1.259 |

| 2009 | 4.803 (4.621 to 4.993) | 3.757 (3.688 to 3.828) | 1.046 | 1.278 |

| 2010 | 4.710 (4.530 to 4.896) | 3.686 (3.618 to 3.755) | 1.024 | 1.278 |

| 2011 | 4.499 (4.328 to 4.677) | 3.578 (3.512 to 3.645) | 0.921 | 1.258 |

| 2012 | 4.447 (4.278 to 4.622) | 3.480 (3.416 to 3.545) | 0.967 | 1.278 |

| Per cent reduction†‡ 1992–2012 |

39.2 | 29.8 | 58.9 | 41.4 |

*Rates are directly adjusted for age using a negative binomial regression model; 95% CIs have been included.

†Per cent rate reductions and absolute rate differences are relative to the 1992 age-adjusted rate or difference calculated as 100* |(age-adjusted rate2012 − age-adjusted rate1992|)/(adjusted rate1992) and per cent change in absolute differences as 100* |(age-adjusted risk difference2012 − age-adjusted risk difference1992|)/(age-adjusted risk difference1992).

‡Per cent reductions for the ratios are relative to a 1.00 reference point (sex equivalence) calculated as 1 − ratio2012/ratio1992.

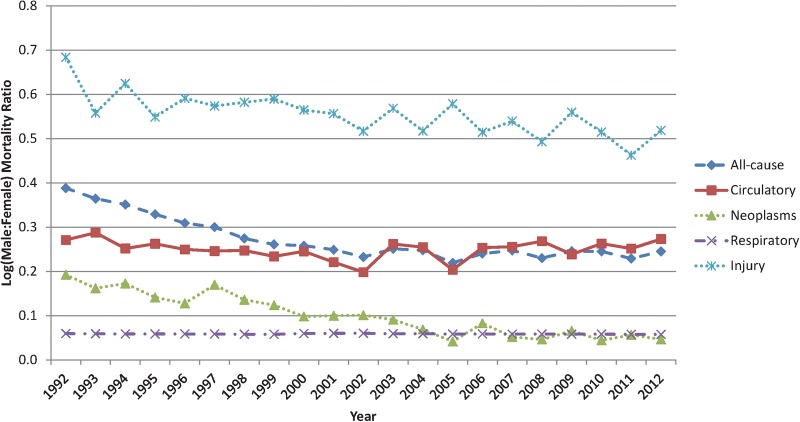

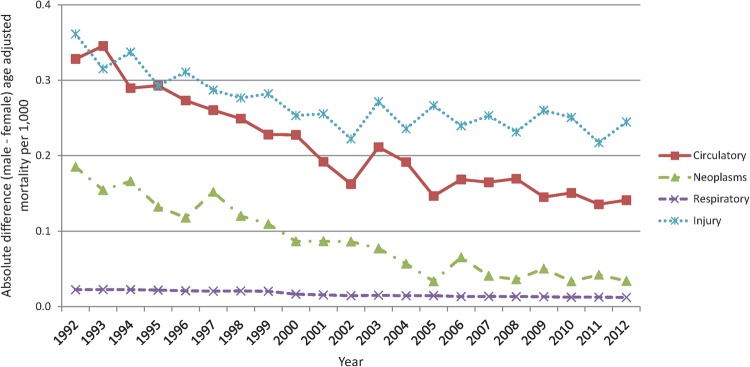

Cause-specific mortality rates also declined for both sexes; albeit, to varying degrees. At the start of the study period, the relative difference between men and women were highest for circulatory deaths. However, by 2012 circulatory mortality rates for men and women were similar to the sex-specific difference among cancer-related deaths (figure 2). For circulatory-related deaths, absolute declines were greater among men (figure 3); although, the relative decline over time was similar between the sexes. In contrast, cancer deaths declined more rapidly among men (29.1%) than women (18.0%). Respiratory deaths showed a similar pattern with greater declines occurring among men compared to women (43.8% vs 25.3%, respectively). Although relatively stable over the study period, injury-related deaths declined by 17.1% among men versus 2.2% among women.

Figure 2.

Logged (positive values of the logged ratio indicate higher male:female morality rates) age-adjusted male:female sex ratio of all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

Figure 3.

Absolute difference (a value of 0 indicates no difference between male and female mortality rates) between men and women for cause-specific mortality by year, adjusted for age.

Notably, cause-specific changes were greatest for men compared to women for all conditions and age groups; the only exception was for the 45–54 age group, where female reductions were consistently greater across most causes of death, excluding respiratory conditions (figure 4). For all age groups 35 years of age and older, the greatest reductions were seen among cardiovascular disease-related deaths; notably, a >60% reduction in cardiovascular mortality was observed for men and women over 65 years of age (table 2). Overall, all-cause 20-year mortality fell by 39.5% and 32.4%, respectively, among men and women under the age of 75.

Figure 4.

Logged age-adjusted all-cause mortality rates by sex, year and income quintile (1992–2012) for the lowest and highest census income quintiles.

Table 2.

Per cent change* in cause-specific mortality rates for men and women (2012 minus 1992)

| Age in years | Males (%) |

Females (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circulatory | Neoplasms | Respiratory | Injuries | Circulatory | Neoplasms | Respiratory | Injuries | |

| <35 | −30.8 | −34.0 | −21.9 | −29.0 | −42.5 | −22.9 | −63.1 | −23.1 |

| 35–44 | −46.6 | −33.8 | −37.2 | −20.6 | −22.6 | −32.9 | 34.9 | −13.6 |

| 45–54 | −43.0 | −27.4 | −33.9 | 5.2 | −53.2 | −31.8 | −25.8 | −3.5 |

| 55–64 | −57.7 | −40.4 | −34.7 | 1.6 | −55.3 | −31.4 | −20.9 | 11.2 |

| 65–74 | −62.7 | −33.4 | −42.8 | −10.1 | −64.0 | −22.8 | −22.1 | −21.0 |

| 75–84 | −58.9 | −17.8 | −41.9 | −3.2 | −58.6 | −1.1 | −17.7 | 26.7 |

| 85+ | −53.1 | −19.7 | −44.3 | 0.1 | −52.0 | 0.9 | −26.5 | 17.4 |

*Calculated as 100 × (age-specific rate2012 − age-specific rate1992)/(age-specific rate1992), where a positive value indicates a reduction in age-specific mortality rates during 1992–2012; in contrast, a negative value indicates an increase in age-specific mortality.

Sex-specific mortality rates differed substantially according to SES; that is, neighbourhood-level income quintile. In every year, age-adjusted rates were highest among those in the lowest income quintile; this was true for both sexes. Over the 20-year period, all-cause mortality rates were on average 28% higher among men in the lowest compared to the highest income quintile; similarly, low-income women experienced mortality rates 24% higher compared to their high-income counterparts (see online supplementary figure S1). Moreover, relative and absolute mortality differences have increased between the highest and lowest income quintile over time. Critically, this has occurred to a greater extent among women, such that from 2000 onwards, high-income men experienced lower mortality all-cause rates than women in the lowest income quintile (figure 5). This demonstrates the only such instance in our analysis where subgroups of men (ie, high-income men) have consistently lower mortality rates than a subgroup of women (ie, low-income women).

Figure 5.

Age-specific 20-year absolute (A) and (B) relative (per cent change for rates are relative to the 1992 age-adjusted rate or difference calculated as 100 × |(age-specific rate2012 − age-specific rate1992|)/(age-specific rate 1992)) differences in all-cause age-specific mortality (1992–2012).

Discussion

In a large study of all deaths occurring in Ontario during the 20 years spanning 1992 through 2012, we found that mortality rates have significantly declined among men and women. Further, we observed that absolute and relative gaps between female and male mortality have decreased over time, with nuanced patterns across age, causes of death and SES. This study includes all deaths that occurred in Canada's largest province Ontario, representing a true population-based picture of mortality trends in the context of a universal healthcare system, and covers two decades of data, allowing for stable observations regarding persistent trends. Importantly, the richness of the data allow for study across causes of death and SES, which are important for assessing changes in absolute and relative inequities over time.

Although sex differences widened for the better part of the twentieth century,8 the findings of this study are consistent with more recent analyses from high-income countries suggesting that the mortality gap between men and women is narrowing in recent years—for all causes combined,14 for specific causes of death, such as cardiovascular disease,7 and among certain age groups.15 One proposed explanation for the narrowing of the mortality gap is the idea that women are increasingly taking up risky behaviours (and ‘quitting’ them less successfully), particularly those which have historically been more prevalent among men; for example, diffuse uptake of tobacco cigarette use.16 This has certainly been reflected within lung cancer and some respiratory mortality trends; however, this has not consistently been predictive of changes in coronary deaths.4 7 Although mortality declines have been occurring across all outcomes and in both sexes, these data show that mortality reductions have been greater and have occurred earlier, among men, as opposed to solely the recent uptake in risk factors among women.17 A review on sex differences by Oksuzyan et al6 suggests that differential patterns in healthcare usage as well as social roles in society also contribute to sex differences in mortality, in addition to changing risk factor patterns.18 Further data on risk factors and healthcare usage according to sex are needed to attribute the root causes of the observed trends.

The narrowing sex mortality gap has important clinical and prevention implications, particularly given the apparent possibility of convergence in the near future and the SES-related convergences observed in this study. The dramatic decline in cardiovascular deaths over the past 30 years has been in large part attributed to medical treatment and improved control of precursor conditions, such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia,17 19 20 although studies have also emphasised the importance of changing risk factors, such as tobacco use and dietary changes.21 Given that absolute and relative differences are narrowing, one such explanation is that men have benefited more from these curative and preventive interventions. This could be as a result of a perceived female mortality advantage that has shaped clinical practice. Another consideration is that men tend to experience clinically important cardiovascular disease earlier in life than women. As a result, well-established survival benefits, of improved treatment for these conditions such as myocardial infarction and stroke, may impact more on men than on women because they receive that treatment earlier and for longer periods. It is noteworthy that women may have lagged in the declining burden of chronic disease risk factors relative to men; however, their mortality rates are also falling. This indicates that gains are being made by both genders, but differentially. Further studies that focus on specific sex differences in mortality amendable to medical and preventive interventions are needed to determine if a sex-specific bias is occurring in clinical practice and how much this bias may be contributing to the narrowing sex ratios relative to changes in sex-specific lifestyle factors, such as smoking. Indeed, continued improvements in equity of access to and use of evidence-based medical care and preventive measures will be necessary to achieve further reductions in the sex mortality gap. This and the potential that unforeseeable events may disrupt these observed trends, (ie, additional differential sources of mortality between men and women) may emerge, further warrants the need for additional studies into the potential convergence of sex-specific mortality rates. Such studies should also investigate sex-and-gender related aspects of health and social planning, such as spousal caregivers, retirement housing and pensions.

The age-specific analyses presented here demonstrate that the largest reductions are being seen in the older ages for men and women. Although gains in men were typically greater overall, this was not the case among the middle age groups where relative reductions between men and women were quite similar. Nor was it the case for cardiovascular and cancer deaths among 45–54-year-old age groups, where gains were slightly larger for women. Other studies have also suggested that mortality trends among middle age groups diverge from overall trends and can be influenced by race, sex and social deprivation,22 23 reflecting a complex interplay of social and behavioural factors. Men experienced greater declines in mortality among older ages. Given that disability is much more common among these older groups, this finding may be signalling that previously demonstrated trends in mortality advantage for disabled women, compared to men, may indeed be changing.24

Despite the narrowing of sex differences, convergence was not noted for any cause or age group; however, an exception was noted across income quintiles. Specifically, there has been a consistent mortality advantage for high-income men compared to low-income women in Ontario since the year 2000. This suggests that high-income men have benefited from these mortality improvements to a greater degree than low-income women. This is in contrast to the evidence prior to 1990, which suggests that socioeconomic inequalities in all-cause mortality were smaller among women compared to men.25 These sex-specific SES-related differences may reflect reduced risk factor burden and possibly better medical treatment among those of higher SES that actually transcend the female mortality advantage. An increase in risky behaviours, such as smoking, specifically among women of low SES may also be contributing to these differences. This is significant because it signals that this gap is potentially amendable to change, which would not be the case if it were entirely driven by biologically and need-based differences. It also signals a worrying disparity that was stable for a large part of the study period, particularly given access to a universal healthcare system. Although SES inequities in mortality are well documented,25–27 the fact that these inequities may be greater between low-income women and higher income women is not as well established but was clearly and persistently demonstrated in this study. Mackenbach has suggested that in order to achieve greater relative SES declines focused efforts are needed among low-SES groups.28 Importantly, our study shows that in order to achieve equal declines among men and women, more directed efforts will not only be needed among lower SES populations but also specifically among women of low SES.

Several study limitations are worth noting. First, although all-cause mortality is a more accurate outcome, cause-specific mortality may be subject to coding misclassification. Specifically, validation studies have shown that while cause of death information from death certificates are quite accurate for cancers and injuries,29 30 they may overestimate deaths from heart disease.31 We acknowledge this possibility; however, we think it is unlikely that these misclassification errors differentially affect men over women and, thus, are unlikely to modify our conclusions. Second, we chose to present an overall picture of mortality trends in a large population; however, certain disease-specific outcomes may display and demonstrate differing trends, which will be topic of future study. Furthermore, data on risk factors (eg, smoking), healthcare usage and changes to medical treatment were not available for this study but can provide further information on the determinants of these trends. Third, we used an ecological indicator of SES given the available data; while SES gradients using ecological and individual-level indicators have shown to be generally consistent,32 the results might differ if such individual-level information were available. These data do not contain information on race/ethnicity, and thus, we were unable to assess whether sex-specific trends differentially affected certain racial/ethnic groups over time. Finally, these trends may not reflect trends occurring in Canadian counties and other countries with differing healthcare access and/or social policies that result in differing mortality gradients by SES.

Conclusions

In summary, these analyses of all deaths occurring in the most populous Canadian province between 1992 and 2012 demonstrate that the absolute and relative mortality gap between men and women are narrowing. Given the relatively short-time period for this observed change, the factors contributing to these changes could be modifiable, such as lifestyle factors, including smoking, or access to and use of high-quality medical treatment. It is also possible that these changes may be more reflective of sex-specific societal inequalities that are structural in nature, such as differential wages, requiring societal regulation to change them. These interventions options clearly warrant further attention and investigation. The potential for convergence among male and female mortality rates, and the observed convergence between those of high-income men and low-income women, has critical implications for health equity and population health, and more broadly, demographic and social planning.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Laura Rosella at @LauraCRosella

Contributors: LCR and DH conceived the manuscript. AC and LCR ran all analyses. TF, JWF and PDD contributed to analytic plan and study conceptualisation. LCR drafted the manuscript, and all authors edited and critically reviewed the final content.

Funding: This project was funded as an Applied Health Research Question (AHRQ), a process by which government-funded research organisations are funded to answer questions from relevant knowledge users. The Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC), was funded to carry out this AHRQ research question on behalf of Public Health Ontario, Ontario's expert technical and scientific public health organisation. These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES.

Disclaimer: The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study received ethics approval from the University of Toronto's Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Administrative data used for this study could be accessed because of comprehensive research agreements between Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

References

- 1.Helweg-Larsen K, Juel K. Sex differences in mortality in Denmark during half a century, 1943–92. Scand J Public Health 2000;28:214–21. 10.1177/14034948000280031101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt K, Annandale E. Relocating gender and morbidity: examining men's and women's health in contemporary Western societies. Introduction to Special Issue on Gender and Health. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J et al. Social-factors and the gender difference in mortality. Soc Sci Med 1986;23:605–9. 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90154-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldron I. Recent trends in sex mortality ratios for adults in developed-countries. Soc Sci Med 1993;36:451–62. 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90407-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingard DL. The sex differential in mortality-rates—demographic and behavioral-factors. Am J Epidemiol 1982;115:205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oksuzyan A, Juel K, Vaupel JW et al. Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clin Exp Res 2008;20:91–102. 10.1007/BF03324754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Sex matters: secular and geographical trends in sex differences in coronary heart disease mortality. BMJ 2001;323:541–5. 10.1136/bmj.323.7312.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beltran-Sanchez H, Finch CE, Crimmins EM. Twentieth century surge of excess adult male mortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:8993–8. 10.1073/pnas.1421942112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trovato F, Heyen NB. A varied pattern of change of the sex differential in survival in the G7 countries. J Biosoc Sci 2006;38:391–401. 10.1017/S0021932005007212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang SM, Khang YH, Chun H et al. The changing gender differences in life expectancy in Korea 1970–2005. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:1280–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Word Health Organization. Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death, Ninth Revision. Geneva, Word Health Organization, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 12.2015. Conversion Tables (for use with ICD-10-CA/CCI). Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productSeries.htm?pc=PCC85.

- 13.Wilkins R. PCCF+ Version 3J User's Guide (Geocodes/PCCF). Automated Geographic Coding Based on the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion Files, Including Postal Codes to May 2002. Catalogue 82F0086-XDB. Health Analysis and Measurement Group, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trovato F, Lalu N. From divergence to convergence: the sex differential in life expectancy in Canada, 1971–2000. Can Rev Sociol Anthropol 2007;44:101–22. 10.1111/j.1755-618X.2007.tb01149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glei DA, Horiuchi S. The narrowing sex differential in life expectancy in high-income populations: effects of differences in the age pattern of mortality. Popul Stud (Camb) 2007;61:141–59. 10.1080/00324720701331433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Krueger PM et al. Mortality attributable to cigarette smoking in the United States. Popul Dev Rev 2005;31:259–92. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00065.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D et al. 50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368:351–64. 10.1056/NEJMsa1211127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanratty B, Lawlor DA, Robinson MB et al. Sex differences in risk factors, treatment and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: an observational study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:912–16. 10.1136/jech.54.12.912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma J, Ward EM, Siegel RL et al. Temporal trends in mortality in the United States, 1969–2013. JAMA 2015;314:1731–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2388–98. 10.1056/NEJMsa053935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capewell S, Ford ES, Croft JB et al. Cardiovascular risk factor trends and potential for reducing coronary heart disease mortality in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:120–30. 10.2471/BLT.08.057885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Flaherty M, Ford E, Allender S et al. Coronary heart disease trends in England and Wales from 1984 to 2004: concealed levelling of mortality rates among young adults. Heart 2008;94:178–81. 10.1136/hrt.2007.118323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:15078–83. 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pongiglione B, De Stavola BL, Kuper H et al. Disability and all-cause mortality in the older population: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Eur J Epidemiol 201631:735–46. 10.1007/s10654-016-0160-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Groenhof F et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality among women and among men: an international study. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1800–6. 10.2105/AJPH.89.12.1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackenbach J. The persistence of health inequities in modern welfare states: the explanation of a paradox. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:761–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenbach JP, Kulhanova I, Artnik B et al. Changes in mortality inequalities over two decades: register based study of European countries. BMJ 2016;353:i1732 10.1136/bmj.i1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenbach JP. Should we aim to reduce relative or absolute inequalities in mortality? Eur J Public Health 2015;25:185 10.1093/eurpub/cku217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.German RR, Fink AK, Heron M et al. The accuracy of cancer mortality statistics based on death certificates in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol 2011;35:126–31. 10.1016/j.canep.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moyer LA, Boyle CA, Pollock DA. Validity of death certificates for injury-related causes of death. Am J Epidemiol 1989;130:1024–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd-Jones DM, Martin DO, Larson MG et al. Accuracy of death certificates for coding coronary heart disease as the cause of death. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:1020–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Long A. Cause-specific mortality by income adequacy in Canada: a 16-year follow-up study. Health Rep 2013;24:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012564supp.pdf (274.7KB, pdf)