Highlights

-

•

Canada Cronkhite syndrome is an evolving disease, with immunological etiology.

-

•

Thrombotic complications have been noted irrespective of a surgical stimulus.

-

•

Elevated factor VIII and fibrinogen are implicated, though thrombophilia profile is normal.

-

•

CCS carries a high risk of complications and mortality, due to its rarity and unavailability of established diagnostic and treatment protocols.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal polyps, Cronkhite Canada syndrome, Pulmonary embolism, Post-operative

Abstract

Introduction

Cronkhite Canada Syndrome (CCS) is a rare syndrome, described in 1955 by Americans, Leonard Wolsey Cronkhite and Wilma Jeanne Canada in the New England Journal of Medicine [1]. About 450 cases have been reported. Complications, like malignant transformation, unprovoked thromboembolism is known. Since there is wide variability in medical presentation, no definitive diagnostic and treatment protocol s have been set. The mortality remains at 55%.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 50 year old male patient presenting with diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, ectodermal features. His upper (UGI) and lower Gastrointestinal (LGI) endoscopy showed multiple polypoidal and carpet like lesions in fundus, body and antrum of stomach. Videocolonoscopy showed multiple sessile and pedunculated polyps. Multiple biopsies were taken, proving malignancy. Because of poor nutrition, total parenteral nutrition was given for four weeks. After nutritional optimization, he underwent laparoscopic assisted subtotal colectomy. His post-operative course was complicated by the occurrence of pulmonary embolism and anastomotic leak.

Discussion

CCS is an ailment of unknown pathophysiology. Considering what is known so far, patients suffering from CCS are at highest risk of thromboembolic episodes. This seems to be irrespective of surgical intervention. Patients of CCS should have thromboembolic prophylaxis started as soon as a diagnosis is made. They should have thrombophilia profile, fibrinogen level and Factor 8 tested before any intervention is planned.

Conclusion

If CCS presents with a surgical indication, namely malignancy, the patient should be categorized as highest risk for thromboembolic complications and both mechanical and pharmacological prophylaxis be instituted.

1. Introduction

CCS is a diffuse gastrointestinal polyposis syndrome with diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, ectodermal findings of onychodystrophy, alopecia, cutaneous hyper pigmentation, hypogeusia and dysphagia [1], [2]. The incidence is one per million, as per the largest study so far [3]. Diagnosis is based on history, physical findings, endoscopy and histology. The etiology is probably autoimmune or infectious because of inflammatory cell infiltration within the polyps [4]. CCS is also associated with elevated anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and IgG4. It is a relentlessly progressive disease with a variable course and poor prognosis depending mainly on control of protein and electrolyte balance. Mortality exceeds 50% regardless of therapy [4].

2. Case presentation

A 50 years old male patient presented to our hospital with the history of diarrhoea, abdominal pain and significant weight loss (more than ten kg) in the past two to three months. He had features of dysnychia, skin hyper pigmentation and alopecia. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Dysnychia of hand nails.

He was evaluated by upper (UGI) and lower Gastrointestinal (LGI) endoscopy. UGI endoscopy showed multiple polypoidal and carpet like lesions in fundus, body and antrum of stomach. Duodenal bulb also showed large sessile and pedunculated polypoidal lesions involving ampulla (Fig. 2). Videocolonoscopy showed multiple small sessile and large pedunculated polyps from rectum to caecum (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). CT Abdomen (oral and IV radiocontrast) showed thickening of the stomach wall with polyps, mild prominence of small bowel loops with wall thickening and subcentimeter mesenteric nodes. Multiple biopsies were taken during endoscopies. Histopathology confirmed multiple hamartomatous polyps and tubular adenomas. Few adenomas showed moderate to high grade dysplasia (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Other investigations done were complete blood count, biochemistry, BUN and Serum Creatinine, albumin levels and electrolytes. He had hypoalbuminemia. Other laboratory parameters were normal.

Fig. 2.

Duodenal bulb showing large sessile and pedunculated polypoidal lesions involving ampulla.

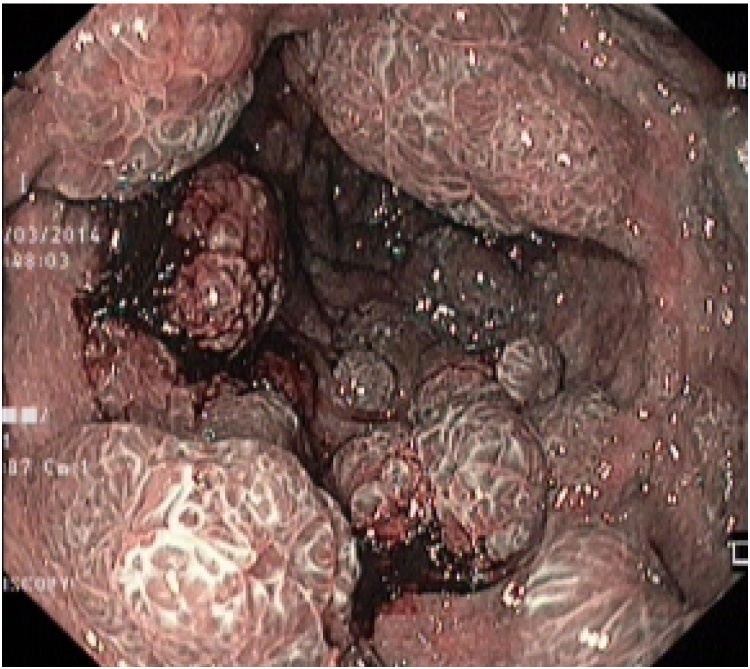

Fig. 3.

Videocolonoscopy showing multiple small sessile and large pedunculated polyps.

Fig. 4.

CTPA showing thrombi in both right and left main pulmonary arteries.

Fig. 5.

Multiple hamartomatous polyps and tubular adenomas.

Fig. 6.

Few tubular adenomas show moderate to high grade dysplasia.

Because of diarrhea, intolerance to oral feeds and poor nutrition, parenteral nutrition was given for four weeks. He underwent laparoscopic subtotal colectomy with iliorectal anastomosis. He had a prolonged but uneventful surgery. Mechanical compression device for thromboembolic prophylaxis was applied intraoperatively. Postoperatively, he was extubated and shifted to surgical ICU for monitoring.

On day one of ICU stay, patient was hypotensive, tachycardic and tachypnoeic. He was saturating 88% on high flow oxygen mask with reservoir bag. He was resuscitated with fluid boluses, later vasopressor support was started. Differential diagnosis of postoperative acute coronary syndrome/pulmonary embolism/sepsis was considered. He had an ECG, 2D Echocardiography, serum procalcitonin done. His procalcitonin was minimally raised. ECG showed right heart strain, there were a deep S in I and q wave in lead III. 2D Echocardiography showed dilated right atrium and ventricle with ventricular dysfunction. A HRCT chest with pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) confirmed thrombi in both the right and left main pulmonary artery (Fig. 4). Since thrombolysis was contraindicated, patient was put on unfractionated heparin. He stabilized over first week. A follow up ultrasound of his abdomen showed a large intraperitoneal collection. An anastomotic leak was suspected to which he succumbed.

3. Discussion

CCS is a rare disease with unknown etiology. Since the number of reported cases are low i.e. 450 worldwide, it has been difficult to classify this disease, set up surveillance and treatment protocols. Most of the information comes from case series. Since its first description by Cronkhite and Canada, various additional clinical features have been noticed. Jarnum and Jensen [9] in 1966 observed protein losing enteropathy and electrolyte disturbances (hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypokalemia). In 1972, Johnson et al., [10] published that the polyps in the stomach and large intestine are hamartomas. Polyps are frequent in the stomach, small and large intestine with esophageal sparing. Etiologically, evidence states that CCS is an immune disorder. The disease is sporadic; no hereditary links have been found though there is one case report of its familiality [11]. CCS is linked to increase anti- nuclear antibodies, [4], [6] and IgG4 plasma cell infiltration of polyps. Immune suppression by corticosteroids and azathioprine may eradicate or lessen manifestations of CCS. Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), is another condition with hamartomas, in which the polyps are distributed through the gastrointestinal tract, but mainly colorectal and polypoidal. It is linked to mutation in BMPR1A or SMAD4 gene. Presence of one of these gene mutation helps to differentiate it from CCS.JPS does not have ectodermal features like onychodystrophy, skin hyperpigmentation. Histopathologically, polyps cannot be differentiated from CCS. There is no definitive treatment for JPS.

The mean age of onset is estimated to be in the fifth-sixth decade with male to female ratio of 3:2 [6]. CCS is known to progress relentlessly and the overall prognosis remains poor. In 15% of CCS patients, stomach or colorectal cancer is identified [4], [7]. Multiple other complications like malnutrition, protein losing enteropathy, recurrent infections, gastrointestinal bleed, adenocarcinoma, rib fractures, thrombosis are seen [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Indications for surgery include malignant transformation, recurring polyps inspite of optimal medical management. Surgical outcomes are poor with mortality exceeding 50% [6], [8].

In a case report by Sampson et al. [6] their patient had repeated occurrences of pulmonary and distal arterial thrombosis inspite of adequate duration of anticoagulation. The thrombosis recurred with every attempt to stop anti-coagulation. His thrombophilia profile was normal but he had an elevated level of fibrinogen and Factor 8. There are other reports of venous thrombosis in CCS associated with sepsis [13] or malignancy [14]. In all these reports, CCS has not been associated with thrombophilia but they had elevated fibrinogen and Factor 8 levels. We did not investigate our patient for raised fibrinogen and Factor 8 pre operatively. In hindsight, knowledge of increased fibrinogen, Factor 8 and active malignancy would have raised his perioperative risk of thromboembolism and both mechanical and pharmacological methods would be instituted.

4. Conclusion

CCS is an ailment of unknown pathophysiology. Considering what is known so far, patients suffering from CCS are at highest risk of thromboembolic episodes. This seems to be irrespective of surgical intervention. Add to this, surgical stress is likely to augment the incidence of thrombotic events. So, patients of CCS should have thromboembolic prophylaxis started as soon as a diagnosis is made. Also, when managing CCS, patients should have their thrombophilia profile, fibrinogen level and Factor 8 tested before any intervention is planned.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest.

Sources of funding

No funding was granted. There are no sponsors for this project.

Ethical approval

Since this is a case report, ethics committee approval was not needed.

Consent

I have obtained written consent from the patient’s next of kin. The consent can be provided should the Editor ask to see it.

Author contribution

Dr. Urvi Shukla- study concept,writing the case report, data collection.

Dr. Gajanan Wagholikar—data collection, writing the case report, discussions with the family about informed consent, data analysis.

Dr. Neha Nemade—writing the case report, data collection, processing images.

Guarantor

I, Dr. Urvi Shukla, accept full responsibility for the work. The decision to publish was a joint decision between Dr. Gajanan Wagholikar and Dr. Urvi Shukla.

Contributor Information

Neha L. Nemade, Email: nemade_neha@yahoo.co.in.

Urvi B. Shukla, Email: shuklaurvi@yahoo.com.

Gajanan D. Wagholikar, Email: drgajanan2002@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Cronkhite L.W., Canada W.J. Generalisedgastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia and onychotrophia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1955;252:1011–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195506162522401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweestser S., Broadman L.A. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: an acquired condition of gastrointestinal polyposis and dermatologic abnormalities. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (N.Y.) 2012;8:201–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goto A. Cronkhite- Canada Syndrome: epidemiological study of 110 cases reported in Japan. NihonGeka Hokan. 1995;64:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopacova M., Urban O., Cyrany S., Laco J., Bures J., Rejchrt J. Cronkhite- Canada Syndrome: review of literature. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/856873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oberhuber G., Stolte M. Gastric polyps: an update of their pathology and biological significance. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:581–590. doi: 10.1007/s004280000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampson J.E., Harmon M.L., Cushman M., Krawitt E.L. Corticosteroid-responsive Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated by thrombosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007;52:1137–1140. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samalavicius N.E., Lunevicius R., Klimovskij M., Kildusis E., Zazecksis H. Subtotal colectomy for severe protein-losing enteropathy associated with Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: a case report. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e164–5. doi: 10.1111/codi.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egawa T., Kubota T., Otani Y., Kurihara N., Abe S., Kimata M. Surgically treated Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:156–160. doi: 10.1007/pl00011711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarnum S., Jensen H. Diffuse gastrointestinal polyposis with ectodermal changes: a case with severe malabsorption and enteric loss of plasma proteins and electrolytes. Gastroenterology. 1966;50:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson J.G., Gilbert E., Zimmermann B., Watne A.L. Gardner’s syndrome,coloncancer and sarcoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 1972;4:354–362. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil V., Patil L.S., Jakareddy R., Verma A., Gupta A.B. Cronkhite- Canada Syndrome:a report of two familial cases. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2013;32:119–122. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu Y.Q., Loke S.L. Cronkhite- Canada syndrome. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003;57:917. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)70030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi Y., Yoshikawa M., Tsukamato N., Shiroi A., Hoshida Y., Enomoto Y. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome with colon cancer, portal thrombosis, high titre of antinuclear antibodies and membranous glomerulonephritis. J. Gastroenterol. 2003;38:791–795. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]