Abstract

Objective

In Australia, Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is the predominant zoonotic serovar in humans and is frequently isolated from layer hens. Vaccination against this serovar has been previously shown to be effective in broilers and the aim of this current study was to assess and determine the best vaccination strategy (live or inactivated) to minimise caecal colonisation by S. Typhimurium.

Methods

A long‐term experiment (56 weeks) was conducted on ISABROWN pullets using a commercial live aroA deleted mutant S. Typhimurium vaccine and an autogenous inactivated multivalent Salmonella vaccine (containing serovars Typhimurium, Infantis, Montevideo and Zanzibar). These vaccines were administered PO or by SC or IM injection, either alone or in combination. Pullets were vaccinated throughout rearing (to 18 weeks of age) and sequentially bled for antibody titre levels. The birds, vaccinated and controls, were challenged orally with a field isolate of S. Typhimurium at different ages, held for 21 days post‐challenge, then euthanased and their caeca cultured for the presence of Salmonella.

Results

None of the oral live‐vaccinated groups exhibited lasting protection. When administered twice, the inactivated vaccine gave significant protection at 17 weeks of age and the live vaccine given by SC injection given twice produced significant protection at 17, 25 and 34 weeks.

Conclusions

Vaccination regimens that included parenteral administration of live or inactivated vaccines and thus achieved positive serum antibody levels were able to provide protection against challenge. Hence, vaccination may play a useful role in a management strategy for Salmonella carriage in layer flocks.

Keywords: layer chickens, poultry, Salmonella Typhimurium, vaccines

Abbreviations

- CFU

colony‐forming units

- S. Enteritidis

Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis

- S. Typhimurium

Salmonella ente rica serovar Typhimurium

Salmonella is the most commonly reported microbial agent responsible for human foodborne illness where eggs have been implicated as the cause.1, 2 Food Standards Australia New Zealand estimates that over 12,000 cases of human salmonellosis occur per year in Australia that may be linked to eggs or egg products.3 The Australian poultry industry differs from most other countries in that Salmonella enterica serovar Enteriditis (S. Enteriditis) is not endemic in chicken breeding and egg‐laying flocks.3, 4 Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is the most frequent serovar isolated from Australian egg layer flocks (28.3% of salmonellae isolations from this source) and this situation has been relatively stable for many years.5, 6 It is also the most frequently detected serovar from human salmonellosis cases in Australia, responsible for 28% of cases in 2009.6 Other serovars found at high prevalence in layer flocks are Infantis (18.3% of isolations), Mbandaka (5.4%), Singapore (5.4%) and Kiambu (4.7%), but these each account for less than 5% of human salmonellosis cases in Australia.6

In Europe, vaccination against S. Enteriditis has been important in reducing the prevalence of that serovar within the poultry industry, with a consequent decline in human S. Enteriditis cases.7, 8, 9 This has been followed by targeting of S. Typhimurium and other serovars through vaccination of layers and breeder chickens.10 In Australia, an inactivated autologous Salmonella vaccine (Intervet [now MSD Animal Health, NSW, Aust]) has been used with success by some poultry companies in decreasing the prevalence of undesirable Salmonella serovars in meat chicken breeder flocks.11 The evaluation of an inactivated multivalent Salmonella vaccine has also been performed in Japan12 and the USA.13 A live aroA deletion mutant S. Typhimurium vaccine (Vaxsafe ST®, Bioproperties Pty Ltd, VIC, Aust) has also been released for use in Australia.14 This live vaccine is registered for oral administration to birds at day‐old or any other age, with potential to circumvent early colonisation, and studies have been undertaken to register the use of this vaccine by a parenteral route in Australia.15

Assessment of reduction in Salmonella colonisation and shedding from infected hens is problematic and varies across the literature.4 Faecal shedding of Salmonella does not necessarily reflect the continued presence of the organism in the caecum and cloacal swabbing is not regarded as a good indicator of infection.16 Other studies have demonstrated significant differences in caecal colonisation between vaccinated and control birds over short periods. One study evaluated an attenuated S. Typhimurium vaccine applied at hatch and 10 days and subsequently challenged at 5 weeks of age and showed lower caecal colonisation against controls only at 2–5 days post‐challenge, but results were similar to the controls from 7 to 14 days.17 Another study demonstrated that caecal Salmonella content became low or non‐detectable by 4 weeks post‐challenge in unvaccinated birds.18

A review of Salmonella infection in laying hens noted that most studies conducted with Salmonella colonisation in chickens have been short term (2 weeks) and used single administration of very high infective doses and that this may not reflect the situation for the whole productive life of a commercial layer hen.4 It could be argued that if a vaccine merely lowers organism numbers compared with controls for a short period but natural decline in organism presence is essentially the same after approximately 2 weeks, the vaccine has not really achieved a long‐term improvement compared with no treatment. However, a decline in the cumulative amount of salmonellae shed into the environment during this 2–3 week period could still have beneficial effects in terms of overall challenge levels experienced by the flock.10

In the field it is more likely that exposure to Salmonella serovars is at a low level and moves gradually through the bird population.19 Some birds will be initially colonised for short periods, but will serve as a source of infection for other, as yet unexposed, birds in the flock. In this way the infection is maintained for considerable periods on a flock basis. Some published studies have investigated the duration of immunity from vaccination against salmonellae in chickens, but very few have worked with S. Typhimurium.

The objective of this study was to determine the capability to restrict S. Typhimurium colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract of layer chickens over their productive life span after differing vaccination regimens using live and inactivated Salmonella vaccines.

Materials and methods

Animal ethics

The animal procedures used in this study were jointly supervised by The University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee (approval no. N00/8–2009/2/5144) and Birling Animal Ethics Committee (approval no. 1038/12/10US), the latter supervising procedures within Zootechny Pty Ltd's facilities. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Animal Research Act of NSW (1985) and Regulations (2005) following the NHMRC Guidelines (2008) and NHMRC/ARC Code of Conduct (2007).

Layer stock

Commercial day‐old brown‐egg layer chicks (Rhode Island Red × Rhode Island White hybrid) were obtained from a commercial hatchery (Baiada Poultry Pty Limited, NSW, Aust). Birds were supplied already vaccinated against Marek's disease, Newcastle disease and infectious bronchitis from the hatchery and, during rearing, all birds received vaccinations against fowl pox (at 2 weeks of age; Intervet/MSD Animal Health, batch no. 3961–009), Newcastle disease (4 weeks of age; Vaxsafe® ND, Bioproperties Pty Ltd, batch NDV073371A), infectious bronchitis (4 weeks of age; Vaxsafe® IB (I), Bioproperties Pty Ltd, batch no. IB1062831A) and infectious laryngotracheitis (8 weeks of age; Pfizer SA2, batch no. 1570114A), following common commercial practices using vaccines commercially available in Australia.

Salmonella vaccines

Two vaccines were used in this study. An Australian‐developed live‐attenuated aroA deletion mutant S. Typhimurium vaccine (Vaxsafe® ST: Strain STM‐1, batch no. STM071421A, Bioproperties Pty Ltd) and coded as ‘V’, and an autologous multivalent inactivated Salmonella vaccine (Intervet/MSD Animal Health, batch no. 4078A‐031), coded ‘N’. The inactivated vaccine contained field isolates of serovar S. Typhimurium DT12 (serogroup B1), Infantis (serogroup C1), Montevideo (serogroup C1) and Zanzibar (serogroup E1) at 108 colony‐forming units (CFU) of each serovar per bird dose. This vaccine contains thiomersal and formalin and was used under Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) permit number 10434.

Challenge organisms

The objective in this study was to simulate field conditions as closely as possible; therefore, a recent field isolate of S. Typhimurium was used rather than a laboratory‐manipulated strain. A challenge strain of S. Typhimurium DT108 was selected from a low‐passage culture of a recent poultry field isolation and was stored in Cryovials (Pro‐Lab Diagnostic, Ontario, Canada; REFPL.170/M) at −80°C.

For each challenge, a bead from a Cryovial was incubated in 100 mL of buffered peptone water (Oxoid ThermoFisher, CM509, Hampshire, UK) to produce a seed culture. Purity of the culture was checked on nutrient agar and identity was confirmed serologically using antisera (Pro‐Lab Diagnostic; refs TL6002 [O], TKL6001 [H], RL6011‐04 [B]). Isolated colonies were selected and suspended in 9 mL of 0.1% peptone water to give a 75% transmittance (1.0 McFarland), equating to 2 × 108 CFU/mL (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France; 47100‐00 DR 100 colorimeter). The target inoculum required for challenge or recovery experiments was achieved through decimal dilution of the initial suspension in accordance with AS5013.10 (2009) (equivalent to ISO6579:2002, MOD), and confirmed by spread plate enumeration on chromIDTM Salmonella agar (bioMérieux® Australia Pty Ltd, QLD, Aust; ref. 04913).

Vaccine trials

Management and sampling of stock

The chicks were placed in floor pens at a research facility (Zootechny Pty Ltd) at 70 birds per pen and reared to 13 weeks of age. The facility consisted of a small commercial‐style chicken shed with an insulated roof and side curtains, providing floor pens of 6.5 m2, each fitted with a bell waterer and two tube feeders. A gas‐fired space heater (Hired Hand®) provided artificial heat during brooding.

Commercial bagged layer starter, grower and laying rations (Barastoc Feeds, Ridley Agriproducts, VIC, Aust) were fed to all birds throughout the experiment. These feeds contained neither antibiotics nor any products such as organic acids that may inhibit Salmonella.

Day‐old chick box paper, as well as subsequent drag swabs of all floor pens collected at 2, 4, 6, 9 and 11 weeks of age, were cultured for Salmonella. At 13 weeks of age, reared birds were transferred to individual layer cages at the Poultry Research Foundation's poultry unit (The University of Sydney, Camden, NSW, Aust) and maintained under production conditions.

The birds underwent a number of vaccination regimens involving the live and inactivated vaccines by various routes and at differing times as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vaccination protocols using live and inactivated Salmonella vaccines in layer hens

| Group code | Vaccination regimen |

|---|---|

| C | No vaccination – control group |

| V0‐V3 | Livea vaccine PO at day‐old and 3 weeks |

| V0‐V3‐N12 | Livea vaccine PO at day‐old and 3 weeks and inactivatedb vaccine IM at 12 weeks |

| V0‐V3‐V6 | Livea vaccine PO at day‐old, 3 and 6 weeks |

| V0‐V3‐V6‐N12 | Livea vaccine PO at day‐old, 3 and 6 weeks and inactivatedb vaccine IM at 12 weeks |

| N6‐N12 | Inactivatedb vaccine IM at 6 and 12 weeks |

| V0‐V3‐N6‐N12 | Livea vaccine PO at day‐old and 3 weeks; inactivatedb vaccine IM at 6 and 12 weeks |

| VS4‐VS8 | Live vaccine by SC injectionc at 4 and 8 weeks |

| V0‐V4‐V14 | Livea vaccine PO at day‐old, 4 and 14 weeks |

Challenge model

The challenge model used has been previously described.11 At various ages (4, 12, 17, 25, 34 and 56 weeks) between 8 and 12 birds per vaccination group were selected at random and removed to experimental pens or cages in a different location and challenged with an oral dose of a field isolate of S. Typhimurium. At 56 weeks of age the regimens that had not shown significant protection against colonisation at 17, 25 or 34 weeks were not tested.

The challenge dose was selected in an attempt to provide a realistic reflection of possible exposure in the field, without resorting to unrealistic levels.11 Successful colonisation of the control birds proved to be inconsistent at various ages. Hence, the challenge dose was varied over time, with 106 CFU per bird used at 4 weeks of age and 108 CFU at 10 weeks of age and thereafter. At 21 days post‐challenge, the birds were euthanased and their caeca aseptically collected and cultured for the presence of Salmonella.

At 4 weeks of age, 10 birds were selected and identified from each group and were maintained unchallenged. These individual birds were bled at 9, 12, 14, 23, 31, 39 and 51 weeks of age to assess serological antibody response to vaccination alone. The serum was examined for the presence of antibody against S. Typhimurium using a commercial ELISA kit (catalogue no. V020, x‐OvO Ltd, Dunfermline, UK) following the manufacturer's instructions. A positive reaction was taken as a sample/positive absorbance ratio > 0.25 at 550 nm, which equates to an ELISA titre of > 785 units (log10 2.89) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Preparation of live vaccine

The live S. Typhimurium vaccine (1000‐dose vial containing 1011 CFU) initially was diluted in sterile phosphate‐buffered saline to a working dose concentration of 108 CFU/250 μL. This dosage was given either by oral gavage using a stepper pipette (Finnpipette®, catalogue no. 4540, Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) or by SC injection using individual 1‐mL hypodermic syringes and a 1‐cm 22‐gauge needle. The live vaccine preparation on each occasion was enumerated by performing decimal dilutions to 10−8 and then cultured duplicates of each dilution onto chromIDTM Salmonella agar to quantify the amount given, using the same methodology as for the challenge inoculum.

Vaccination regimens

There were nine vaccination regimens (including a non‐vaccinated control), coded V or N denoting the vaccine used, followed by the age at administration, in weeks (Table 1). Vaccine dosages used were at current rates recommended by the manufacturers. It must be noted that the manufacturers of Vaxsafe® ST have since reduced their recommended dose rate to 107 organisms per bird for oral inoculation.

Caecal culture and Salmonella detection

All microbiological testing, including the vaccine and challenge strain enumeration, was performed at a NATA accredited laboratory (Birling Avian Laboratories) in accordance with AS5013.10‐2009. The caeca were initially emulsified 1 : 10 in buffered peptone water and then enriched and further cultured as described in the Standard. Isolates were presumptively confirmed using validated commercial chromogenic agar chromIDTM Salmonella agar (bioMérieux Australia).

Typical presumptive Salmonella were confirmed serologically with poly‐O and poly‐H and anti‐serogroup B antisera (Pro‐Lab Diagnostic; refs TL6002, TKL6001 and RL601104) and the slide agglutination technique after subculture on a nutrient agar slope. The confirmed Salmonella isolates were forwarded to the Australian Salmonella Reference Laboratory for complete serological and phage typing.

Statistical analysis

The proportion of birds for which S. Typhimurium was isolated from the caeca was compared between each vaccinated group and the unvaccinated control group using contingency table analysis (Chi‐square or Fisher's exact test if an expected cell value was < 5), performed using the StatCalc function of EpiInfo™ (CDC, 2000). The quantitative serology results using the S. Typhimurium ELISA were analysed using ANOVA and means were separated by Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test using Statistica™ (StatSoft Inc., 2001, Tulsa, OK, USA). Where ANOVA assumptions were not met (as measured by Levene's test for homogeneity of variance), the non‐parametric Kruskal‐Wallis ANOVA was used.

Results

No environmental salmonellae were cultured from the day‐old chick box paper or drag swabs collected in the rearing pens holding the unchallenged birds for the duration of the experiment.

The data summarised in Table 2 show the numbers of birds positive for caecal S. Typhimurium 21 days after each challenge age. At 4 weeks of age, only groups vaccinated prior to this age (V0‐V3 and V0‐V4) were compared with control birds. The low levels of control group colonisation (< 30%) made difficult the determination of statistically significant differences of vaccine effects at 4 and 10 weeks. Colonisation of the control group by the challenge organism of > 50% of birds was achieved at 17, 25 and 34 weeks, with lower colonisation rates observed at 56 weeks (33%). At the 17‐week‐old challenge, 50% colonisation of the control group was observed and a significantly lower caecal colonisation rate (0%) was observed among the groups receiving either two inactivated vaccine doses (N6‐N12) or two live‐vaccine doses by SC injection (VS4‐VS8). Protection was indicated in the group receiving oral live vaccine at 0, 4 and14 weeks of age (V0‐V4‐V14; 12.5% positive after challenge).

Table 2.

Caecal colonisation of layer hens 21 days following challenge with Salmonella serovar Typhimurium

| Vaccination protocol | No. of birds positive in caeca post‐challenge at ages (no. challenged) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 weeks (n = 8) | 10 weeks (n = 8) | 17 weeks (n = 8) | 25 weeks (n = 10) | 34 weeks (n = 10) | 56 weeks (n = 12) | |

| C | 1 | 2 | 5A | 8 | 6A | 4 |

| V0‐V3 | 1 | 0 | 2AB | 4 | 9A | NT |

| V0‐V3‐N12 | NT | 0 | 2AB | 7 | 9A | NT |

| V0‐V3‐V6 | NT | 2 | 6A | 3 | 5AB | NT |

| V0‐V3‐V6‐N12 | NT | 1 | 2AB | 4 | 6A | 4 |

| N6‐N12 | NT | 2 | 0B | 5 | 6A | 5 |

| V0‐V3‐N6‐N12 | NT | 1 | 2AB | 7 | 5AB | 1 |

| VS4‐VS8 | NT | 2 | 0B | 3 | 1B | 7 |

| V0‐V4‐V14 | 2 | 3 | 1AB | 6 | 6A | NT |

| Statistical difference from control | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | P < 0.05* | P = 0.07 | P < 0.05* | P > 0.05 |

Significantly different to the control group.

A,BMeans in the same column without common superscripts differ from the control group (P < 0.05).

NT, not tested.

By 25 weeks, with 80% colonisation of control birds, the VS4‐VS8 and V0‐V3‐V6 groups exhibited levels of colonisation (30%) that approached a statistically significant difference (2‐tailed Fisher's exact test, P = 0.07). There was no remaining protection, however, from the oral live‐vaccinated groups (Table 2), including the V0‐V4‐V14 group. At 34 weeks, only the VS4‐VS8 group retained significant colonisation reduction (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test). No groups showed significant differences to the control group (25% colonisation) when challenged at 56 weeks (Table 2).

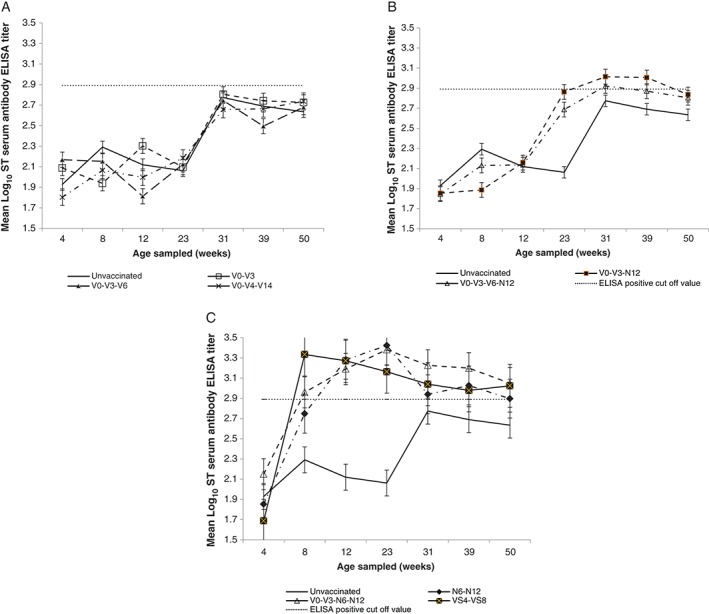

The serological data summarised in Figure 1 show the serum antibody titres in unchallenged birds in the vaccination groups over time. The x‐OvO positive ELISA for antibody to S. Typhimurium cut‐off point (785 or log10 2.89 titre) is marked in Figure 1. The control group gave results well below the ELISA titre cut‐off point (log10 2.89) for a ‘positive’ result for S. Typhimurium antibody at all ages. The serology from the groups that received only live vaccine by the oral route (V0‐V3, V0‐V3‐V6, V0‐V4‐V14) shown in Figure 1A was not different to that of the control group (log10 2.81, 2.74 and 2.66, respectively).

Figure 1.

Mean log10 Salmonella Typhimurium antibody ELISA titres in non‐challenged birds by vaccination groups over time. (A) Groups that received only an oral dose of the live vaccine (Vaxsafe® ST: Strain STM‐1, Bioproperties Pty Ltd, VIC, Aust; live‐attenuated aroA deletion mutant of S. Typhimurium). (B) Groups that received the inactivated vaccine (containing field isolates of serovar S. Typhimurium, Infantis, Montevideo and Zanzibar at 108 CFU of each serovar per bird dose) by IM injection only at 12 weeks of age. (C) Groups that received the inactivated vaccine at 6 and 12 weeks of age or live vaccine by SC injection at 4 and 8 weeks of age. All charts show unvaccinated birds as a reference point and the x‐OvO ELISA positive cut‐off point (log10 2.89). Bars show standard error. CFU, colony‐forming units.

The two groups that received a single dose of the inactivated vaccine (V0‐V3‐N12 and V0‐V3‐V6‐N12) showed negative serum antibody levels at 14 weeks of age (2 weeks post inactivated vaccination), but were positive by 23 weeks of age, remaining at that titre until 31 weeks of age but declining into the negative range thereafter (Figure 1B).

The groups receiving either two inactivated vaccine doses (N6‐N12 and V0‐V3‐N6‐N12) or two live vaccine doses by SC injection (VS4‐VS8) showed rapid seroconversion to antibody titres well above the positive cut‐off, remaining so until 39 weeks of age or longer (Figure 1C). After only a single dose of the live vaccine, injected SC at 4 weeks of age, titres rose to a high level (log10 3.33) by 8 weeks of age. This group thereafter showed a gradual decline to log10 2.98 by 31 weeks, but still remaining serologically positive until 50 weeks of age. A subsequent SC live vaccine injection applied at 8 weeks of age did not appear to increase the titre for this group (VS4‐VS8). Groups receiving two inactivated vaccine doses (N6‐N12 and V0‐V3‐N6‐N12) showed a slower titre rise to a peak at 14 weeks of age (at log10 3.42 and 3.38, respectively) following the second dose at 12 weeks of age.

Discussion

The overall objective of any intervention method for S. Typhimurium control in commercial laying hens is to reduce the amount of the organism that may be passed on via the egg into the human food chain. Hence, such a program must aim to reduce the long‐term carriage of salmonellae in the gastrointestinal tract of layer hens and minimise the opportunity for human pathogenic serovars colonising hens during the laying period.

A notable difficulty in the evaluation of this study was the low levels of caecal colonisation in the control groups. The only ages at which caecal colonisation of control groups exceeded 50% were 17, 25 and 34 weeks, with the low colonisation levels in controls demonstrating that statistically significant protection is impossible, even with zero colonisation of a vaccinated group. Achieving high levels of S. Typhimurium caecal colonisation in experimental control (unvaccinated) chickens has been a common difficulty in many studies. For example, an early study with a live S. Typhimurium aroA deletion mutant vaccine achieved only 20–50% of control birds when challenged at 11 days of age.14 A duration of immunity study using S. Typhimurium challenge, also using a live vaccine, recorded control positives of between 20% and 40% when challenged from 6 to 12 months of age,20 claiming long‐lasting protection even though the later ages did not give statistically significant results. It appears that serovar Typhimurium infections in chickens are quite short term compared with the less invasive but more chicken‐adapted serovar Enteritidis. A review suggested that this may be caused by a more pronounced immune response to serovar Typhimurium, which allows it to be cleared more propitiously from birds.4

Attempts were made in the current study to improve the colonisation of control group birds with S. Typhimurium, firstly by increasing the challenge dose rate, then by increasing the number of birds per group and finally by incorporating mucin in the growth medium for the challenge cultures. An 80% positive colonisation in controls at 25 weeks of age was achieved, though at subsequent ages this rate declined sharply. It was more likely that this higher control colonisation at 25 weeks was related to the reduction in cell‐mediated immunity in hens around point of lay, which has been shown to allow a resurgence of previously suppressed Salmonella infection,21 rather than to the changes in the challenge methodology. This possible mechanism and its effect with serovar Typhimurium needs to be studied more closely in chickens.

Of the vaccine regimens tested in this study, only dual injection of the inactivated vaccine IM (N6‐N12), or the live vaccine SC (VS4‐VS8), delivered significantly lowered S. Typhimurium caecal colonisation rates when challenged at 17 weeks. At 34 weeks, only the VS4‐VS8 treatment significantly reduced colonisation, and all vaccination regimens failed to yield a significant protection at 25 weeks (P = 0.07 for V0‐V3‐V6 and VS4‐VS8 compared with control group). The administration of the live vaccine by the oral route at various ages and numbers of repetitions failed to provide consistent or persistent protection against caecal colonisation. Administration of the live vaccine by the oral route prior to the use of inactivated vaccine did not improve protection against colonisation as compared with the inactivated vaccine used alone. These findings are consistent with another study using a live S. Typhimurium aroA deletion mutant vaccine in broiler breeders where oral administration provided only short‐term protection but subsequent injection of an inactivated trivalent vaccine produced a reduction in caecal colonisation at 22 weeks.22 A field study comparing a vaccination strategy using a combination of multiple oral live vaccinations followed by a killed bacterin of mixed Salmonella serovars to no vaccination in broiler breeders demonstrated lower caecal presence of Salmonella in the vaccinated birds, but this did not allow separation of effects from the individual vaccine types.23

There was no detectable seroconversion seen with the live vaccine given orally in this study. It is important to note that this outcome may only be concluded for the particular vaccine used in this study and may not be the same for other live Salmonella vaccines. Live, orally administered Salmonella vaccines have been shown to elicit cell‐mediated immunity and their protective ability to be mainly reliant on this component of the immune system.24 Serum antibody levels to S. Typhimurium in unchallenged, oral live‐vaccinated chickens were no different to those of unvaccinated control chickens between 14 and 23 weeks of age (Figure 1A). The mean titre for these groups (C, V0‐V3, V0‐V3‐V6 and V0‐V4‐V14) did not reach the positive threshold for the x‐OvO S. Typhimurium ELISA test.

In contrast to our findings, an earlier study using the progenitor to the live vaccine studied here reported significant humoral responses following oral administration at 106 CFU per bird at 21 and 28 days post vaccination.14 That study used a different breed of bird and a custom‐made ELISA, but the difference in the serology results with the current study is stark. This may indicate that the currently studied live vaccine lacked recognition by the host to the same extent as the earlier version. Those authors14 concluded that the vaccine organism was able to colonise the gut for 14–21 days before being eliminated and that this colonisation was necessary for contact with the host tissues long enough to establish a strong immune response. This response was not demonstrable in the current study despite multiple oral exposures at a high dose rate (108 CFU/bird).

Improvement in the control of Salmonella in commercial layer flocks to reduce the risk of foodborne illness requires a program to substantially decrease intestinal colonisation of hens just prior to and throughout their egg production lifetime. Hence, a vaccine must provide enduring protection at least until after the onset of sexual maturity, a physiological age at which cell‐mediated immunity may be compromised.21 The difficulty in producing an experimental challenge colonisation of adult hens, as seen here and in other studies that have evaluated long‐term protection,17, 25 suggests that caecal colonisation by serovar Typhimurium in older hens may be naturally limited. It would appear that protection in the peri‐maturity period, with its associated relaxation of cell‐mediated immunity,21 may be the most important point in time at which a vaccine may provide a reduction in colonisation of hens throughout their entire egg production period. Although cell‐mediated immunity may be suppressed at this time,21 adequate protection at this age may require the pre‐existence of an effective humoral antibody presence in the chicken. The live vaccine given orally did not provoke humoral antibody production and if the existing cell‐mediated protection was compromised around sexual maturity, the comparative failure of protection from this type of vaccine between 17 and 34 weeks of age may be explained. This possible mechanism requires further study.

Protection over any extended time was achieved in this study only where the vaccine, either live or inactivated, was administered parenterally. The inactivated multivalent vaccine used in this study provided significant protection after two applications when birds were challenged at 17 weeks of age but not thereafter, as measured under this challenge system.

In conclusion, oral application of the live S. Typhimurium aroA deletion mutant vaccine used in this study did not provide resistance to colonisation of the caeca with a wild‐strain of S. Typhimurium. However, administration of this live vaccine by the SC route provided strong and longer lasting protection from caecal colonisation. This route of administration of this attenuated vaccine may provide a useful approach to improved control of Salmonella in layer hens.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the best and most cost‐effective method of use of injectable vaccines, including the initial administration of the live vaccine SC followed by the inactivated vaccine IM some weeks later. The ability of these vaccines, alone and in combination, to provide cross protection against other S. enterica serovars also needs to be examined.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Australian Egg Corporation Limited. Vaccines and some financial assistance were provided by Bioproperties Australia and Intervet‐Schering‐Plough Australia (now MSD Animal Health Australia).

We thank Gavin Bailey and Taha Harris (Birling Avian Laboratories, Bringelly, NSW) for their technical microbiological assistance and Jadranka Velnic and Susan Ball (Zootechny Pty Ltd, NSW) and Joy Gill and Melinda Hayter (University of Sydney, Camden, NSW) for assistance with bird husbandry.

References

- 1. Risk assessments of Salmonella in eggs and broiler chickens In: Microbiological risk assessment series 2 . World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; http://www.fao.org/docrep/fao/005/y4392e/y4392e00.pdf 2002. Accessed January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Public health and safety of eggs and egg products in Australia: explanatory summary of the risk assessment. FSANZ , 2009. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/Pages/publichealthandsafet5769.aspx. Accessed March 2015.

- 3. Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Public health and safety of eggs and egg products in Australia. FSANZ , 2009. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/foodstandards/primaryproductionprocessingstandardsaustraliaonly/eggstandard/. Accessed December 2011.

- 4. Wales AD, Davies RH. A critical review of Salmonella typhimurium infection in laying hens. Avian Pathol 2011;40:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray CJ. Salmonella serovars and phage types in humans and animals in Australia 1987–1992. Aust Vet J 1994;71:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davos D, editor. Annual Report of the Australian Salmonella Reference Centre. IMVS , Adelaide, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7. European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . The European Union Summary Report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food‐borne outbreaks in 2010. EFSA J 2012;10:2597, doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2597. [Google Scholar]

- 8. van den Bosch G. Vaccination versus treatment: how Europe is tackling the eradication of Salmonella. Asian Poultry July 2003;1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Woodward MJ, Gettinby G, Breslin MF et al. The efficiency of Salenvac, a Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Enteritidis iron‐restricted bacterin vaccine, in laying chickens. Avian Pathol 2002;31:383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clifton‐Hadley F, Breslin M, Venable LM et al. A laboratory study of an inactivated bivalent iron restricted Salmonella enterica serovars Enteritidis and Typhimurium dual vaccine against Typhimurium challenge in chickens. Vet Microbiol 2002;89:167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pavic A, Groves PJ, Cox JM. Utilization of a novel autologous killed tri‐valent (serogroups B [Typhimurium], C [Mbandaka] and Orion [E]) for Salmonella control in commercial poultry breeders. Avian Pathol 2010;39:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deguchi K, Yokoyama K, Honda T et al. Efficacy of a novel trivalent inactivated vaccine against the shedding of Salmonella in a chicken challenge model. Avian Dis 2009;53:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berghaus RD, Thayer SG, Maurer JJ et al. Effect of vaccinating breeder chickens with a killed Salmonella vaccine on Salmonella prevalences and loads in breeder and broiler chicken flocks. J Food Protect 2011;74:727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alderton MR, Fahey KJ, Coloe PJ. Humoral responses and salmonellosis protection in chickens given a vitamin‐dependent Salmonella Typhimurium mutant. Avian Dis 1991;35:435–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abs El‐Osta Y, Mohotti S, Carter F et al. Preliminary analysis of the duration of protection of Vaxsafe® ST vaccine against Salmonella shedding in layers. Proc Aust Poultry Sci Symp 2015;26:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barrow PA. ELISAs and the serological analysis of Salmonella infections in poultry: a review. Epidemiol Infect 1992;109:361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dueger EL, House JK , Heitoff DM et al. Salmonella DNA methylase mutants elicit protective immune responses to homologous and heterologous serovars in chickens. Infect Immun 2001;69:7950–7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stern NJ. Salmonella species and Campylobacter jejuni caecal colonisation model in broilers. Poultry Sci 2008;87:2399–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lister SA, Barrow P. Enterobacteriaceae In: Pattison P, McMullin P, Bradbury JM. et al., editors. Poultry diseases, 6th edn Elsevier, Edinburgh, 2008;111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hassan JO, Curtiss R III. Efficacy of a live avirulent Salmonella Typhimurium vaccine in preventing colonisation and invasion of laying hens by Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Enteritidis. Avian Dis 1997;41:783–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wigley P, Hulme SD, Powers C et al. Infection of the reproductive tract and eggs with Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum in the chicken is associated with suppression of cellular immunity at sexual maturity. Infect Immun 2005;73:2986–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bailey JS, Rolon A, Hofacre CL et al. Resistance to challenge of breeders and their progeny with and without competitive exclusion treatment to Salmonella vaccination programs in broiler breeders. Int J Poultry Sci 2007;6:386–392. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dorea FC, Cole DJ, Hofacre CL et al. Effect of Salmonella vaccination of breeder chickens on contamination of broiler chicken carcasses in integrated poultry operations. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010;76:7820–7825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Springer S, Lindner T, Ahrens M et al. A new live Salmonella Enteritidis vaccine for chicken: experimental evidence of its safety and efficacy. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 2000;113:246–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hassan JO, Porter SB, Curtiss R III. Effect of infective dose on humoral immune responses and colonisation in chickens experimentally infected with Salmonella Typhimurium. Avian Dis 1993;37:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]