Abstract

Objective

To define a minimum Standard Set of outcome measures and case‐mix factors for monitoring, comparing, and improving health care for patients with clinically diagnosed hip or knee osteoarthritis (OA), with a focus on defining the outcomes that matter most to patients.

Methods

An international working group of patients, arthroplasty register experts, orthopedic surgeons, primary care physicians, rheumatologists, and physiotherapists representing 10 countries was assembled to review existing literature and practices for assessing outcomes of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic OA therapies, including surgery. A series of 8 teleconferences, incorporating a modified Delphi process, were held to reach consensus.

Results

The working group reached consensus on a concise set of outcome measures to evaluate patients’ joint pain, physical functioning, health‐related quality of life, work status, mortality, reoperations, readmissions, and overall satisfaction with treatment result. To support analysis of these outcome measures, pertinent baseline characteristics and risk factor metrics were defined. Annual outcome measurement is recommended for all patients.

Conclusion

We have defined a Standard Set of outcome measures for monitoring the care of people with clinically diagnosed hip or knee OA that is appropriate for use across all treatment and care settings. We believe this Standard Set provides meaningful, comparable, and easy to interpret measures ready to implement in clinics and/or registries globally. We view this set as an initial step that, when combined with cost data, will facilitate value‐based health care improvements in the treatment of hip and knee OA.

INTRODUCTION

Total expenditures on health care as a percentage of the gross domestic product continue to rise worldwide 1. Yet the World Health Organization estimates that 20–40% of health care costs are unnecessary 2. Uncertainty about health outcomes combined with increasing costs has driven interest in value‐based health care (i.e., the idea of competition on value rather than volume in health care), where value is defined as the ratio between patient outcomes and the costs necessary to achieve those outcomes. By focusing on the measurement and reporting of outcomes that matter to patients over the full cycle of care, value‐based health care empowers patients to make informed choices about their care and enables providers to improve outcomes, increase efficiency, streamline care processes, and decrease the costly and inefficient fragmentation of care delivery 3. Currently, a major challenge in measuring value in health care is the lack of universal metrics for defining value. Therefore, in an effort to facilitate the transition to value‐based health care, the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) convenes international working groups to develop standardized and concise outcome measure sets for specific medical conditions, with a focus on the outcomes that matter most to patients (www.ichom.org).

Box 1. Significance & Innovations.

The work presented here expands upon current regional and national registry efforts from around the globe and represents the first internationally developed core outcome set for the evaluation and comparison of the treatment of hip or knee osteoarthritis (OA) in clinical practice across providers, regions, and countries.

This work also expands upon current registry efforts by providing a single set of outcome measures to evaluate the full continuum of care for hip and knee OA, from self-managed and symptomatic treatment to total joint replacement surgery.

Hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) are among the leading causes of global disability, with an aging and increasingly obese population worldwide likely to increase its prevalence 4. The total annual cost of OA per patient has been estimated to be as much as $5,700 in the US 5. Pain and impaired joint function are the main limiting symptoms affecting patients with OA, which typically develops over the course of many years, with varying symptom intensity over time 6. The modern management of symptomatic hip or knee OA involves holistic assessment and selection of therapies from a wide range of options, ranging from lifestyle interventions and education to oral medication and joint replacement surgery 7. All patients should be offered basic treatment options such as lifestyle interventions and education 8. Many patients will require options such as physiotherapy, walking aids, oral medication, or intraarticular injections. If nonsurgical treatment alternatives are insufficient to control symptoms, a smaller group of patients may be candidates for joint replacement or other surgical interventions.

The field of orthopedics is a leader in the measurement of outcomes and use of patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs). Joint replacement registries have demonstrated how routine measurement of outcomes can improve clinical practice by eliminating low‐value treatments or harmful implant devices 9, 10. However, most joint registries focus on postmarket surveillance of implants rather than patient‐reported satisfaction and function. Moreover, joint replacement represents only a fraction of all care associated with hip and knee OA.

Previous efforts at defining universal standards for measuring hip and knee OA outcomes have focused on assessment of physical functioning and metrics for use in clinical trials 11, 12. However, there is no common definition of key outcome measures for use in clinical care across all treatments for this condition. The objective of this work was to define a minimum Standard Set of outcome measures and case‐mix factors for evaluating, comparing, and improving the clinical care of patients with hip or knee OA, with a focus on the outcomes that matter most to patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Working group assembly and composition

This work was initiated by ICHOM, a nonprofit organization focused on the development and international adoption of standardized outcome measures for major medical conditions. ICHOM convened a working group composed of 2 patient representatives and 21 international experts in various fields of OA care and research. The working group provided balanced representation across geographic locations, medical specialties, and existing joint replacement registries and international initiatives as shown in Supplementary Appendix A (available on the Arthritis Care & Research web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.22868/abstract). The activities of the working group were coordinated by a project team consisting of a working group lead (PDF), 2 project leaders (LvM and SW), a research fellow (OR), and the ICHOM Vice President of Research and Development (CS).

Work process and decision‐making

The Standard Set was developed using a modified Delphi process 13. Between July 2014 and March 2015, 8 teleconferences were held by the working group. Each teleconference had a specific goal, such as establishing the scope of the Standard Set, defining the patient population, selecting the appropriate outcomes and case‐mix domains, and defining the relevant metrics. For each topic, the project team reviewed the existing literature and current practices and gathered input from expert interviews to develop proposals for discussion at the teleconference. Detailed minutes of these discussions were distributed to working group members, who voted on each item of the project team's proposal via online survey. Each item required a 67% majority vote of survey respondents to be included in the Standard Set. Survey items with less than 67% majority were either excluded from the Standard Set or revised by the project team and presented again for discussion and voting at the next teleconference.

RESULTS

Response rates and scope

Response rates for the 6 post‐teleconference surveys were 90%, 85%, 71%, 84%, 85%, and 84%, respectively. Group size fluctuated slightly due to the late addition of some members and temporary leaves of absence of others. The working group first defined the patient population for which outcomes are to be measured. The diagnosis of hip or knee OA is not always straightforward. Patients with radiographic signs of OA may not have any symptoms while others with severe symptoms have no radiographic changes. Therefore, diagnosis is based on an overall assessment of risk factors, symptoms, and clinical examination 14. There are a variety of treatment options available to meet patients’ needs, depending on the severity of symptoms and stages of disease. Due to this complexity, we decided that the Standard Set should target all patients with clinically diagnosed, symptomatic OA of the hip or knee, regardless of treatment. There was unanimous agreement with this scope within the working group.

Outcome domains and measures

Hip and knee pain, hip and knee function, health‐related quality of life (HRQOL), and work status formed the core outcome domains, reflecting the main limiting symptoms of hip and knee OA. Table 1 shows all outcome domains and measures included in the Standard Set and the percentage of working group members who agreed with their inclusion. The selection of measures to capture the outcome domains above was based on an assessment of the domain coverage, psychometric properties, feasibility to implement, and clinical interpretability of available measures. We aimed to balance pragmatism with comprehensiveness by selecting instruments that adequately capture the relevant domains in a parsimonious manner.

Table 1.

Outcome domains and definitions included in the Standard Seta

| Category and outcome domain | Outcome definition | Agreementb |

|---|---|---|

| Patient‐reported health status | ||

| Hip and/or knee function | Tracked via HOOS‐PS or KOOS‐PS | 100 |

| Pain in hips, knees, or lower back | Tracked via numeric or visual analog rating scales | 88 |

| Quality of life | Tracked via EQ‐5D‐3L, SF‐12, or VR‐12 | 100 |

| Work status | What is your work status? Unable to work due to a condition other than osteoarthritis; unable to work due to osteoarthritis; not working by choice (student, retired, homemaker); seeking employment (I consider myself able to work but cannot find a job); working part‐time; working full‐time | 77 |

| Satisfaction with results | How satisfied are you with the results of your treatment? Very satisfied; satisfied; neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; unsatisfied; very unsatisfied | 88 |

| Surgical outcomes | ||

| Death | All‐cause 30‐day mortality | 100 |

| Admissions | All‐cause 30‐day readmissions | 88 |

| Reoperation | Any consecutive open surgery performed on the hip or knee. Includes both minor and major reoperations. Minor revision: any reoperation with removal, exchange, and/or addition of minor implant part (e.g., head, liner). Major revision: any reoperation with removal, exchange, and/or addition of major implant part (e.g., cup, femoral component, tibial component) | 94 |

| Disease progression | ||

| Treatment progression | Which of the following treatments have you undergone in the past year for your osteoarthritis related hip or knee problems? (Tick all that apply) Information/ advice (ex: patient education, advice on diet, exercise, or other lifestyle alterations); self‐managed care (ex: nonprescription oral pain medication, medications applied to the skin, exercise, or diet program); nonsurgical, clinical care (ex: nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or other prescription drugs, supervised physical or occupational therapy, orthosis or other ambulatory aids, injections directly into the joint); surgery (ex: osteotomy, resurfacing, partial or total joint replacement) | 82 |

| Care utilization | In the past year, which of the following health care providers have you seen for treatment of your osteoarthritis‐related hip or knee problems? (Tick all that apply) Health educator/peer support group, dietician, physical therapist, or general practitioner; rheumatologist; orthopedic surgeon; alternative health practitioner | 82 |

HOOS‐PS = Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score short version; KOOS‐PS = Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score short version; EQ‐5D‐3L = EuroQol 5‐domain instrument with 3 levels; SF‐12 = Short Form 12 health survey; VR‐12 = Veterans Short Form 12 health survey; ex = example.

Percentage agreement among survey respondents.

Hip‐ and knee‐specific PROMs

A variety of PROMs instruments for evaluating hip and knee function exist. The 24‐item Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) assesses pain, disability, and joint stiffness in patients with hip and knee OA 15 and has proven valid, reliable, and responsive to OA outcomes 15, 16. However, in addition to being lengthy, it requires a licensing fee to use, potentially limiting broad implementation. The 12‐item Oxford Knee and Hip Scores assess pain and function and were designed to measure outcomes following joint replacement surgery 17, 18. They are widely used in clinical studies and joint replacement registries, but how applicable they are to the general OA population is unclear, and they require a license for use. Developed as extensions of the WOMAC, the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) are nonproprietary comprehensive alternatives 19, 20. However, these questionnaires are long (42 and 40 items, respectively), representing a burden to the respondent. Fortunately, short versions (the KOOS‐PS and HOOS‐PS) have been developed, consisting of 7 and 5 questions, respectively. Despite their brevity, these instruments exhibit good measurement properties in the domain of physical functioning and are free of charge to use. The KOOS‐PS has been translated into 15 languages, including the 4 most widely spoken, and the HOOS‐PS has 10 translations. Following careful consideration, the working group agreed to recommend use of the KOOS‐PS and HOOS‐PS as measures of hip and knee function in the Standard Set 21, 22.

The HOOS‐PS and KOOS‐PS do not include a measure of pain. It is common to assess pain using visual analog scales (VAS) or numeric rating scales (NRS). Despite their differences in granularity, possible modes of collection, and presentation requirements, these instruments provide congruent results 23. Therefore, to facilitate implementation and align with current practices, the working group agreed to recommend assessment of joint pain via either VAS or NRS (11‐item version) using a 1‐week recall period 19, 20. Given the prevalence of multijoint OA, the group also agreed that pain would be assessed for all 4 relevant joints (i.e., the right hip, left hip, right knee, and left knee) as well as the lumbar spine.

HRQOL PROMs

There are several tools available to measure HRQOL in patients with hip or knee OA. However, existing practices and the volume of supporting research narrow the options to 2 main alternatives: the Short Form health surveys (available at www.sf-36.org) and the EuroQol health outcome measures (available at www.euroqol.org). The Short Form 36 health survey (SF‐36) assesses 8 dimensions of health, which can be summarized into a physical health and mental health composite score 24. As the most commonly used generic PROM in clinical trials, the SF‐36 has proven to be a psychometrically sound tool for patients with OA 25. However, the shortened version, SF‐12, is preferred for routine followup in joint replacement registries for practicality of data collection 26.

The EuroQol 5‐domain instrument (EQ‐5D) is a generic measure of health status developed by the EuroQol Group 27. It consists of questions assessing 5 health outcome domains, which can be summarized into a single score, and a VAS assessing current overall health state. Although alternative versions exist, the original EQ‐5D with 3 levels of response options is by far the most commonly used and best validated in OA patients 28.

Whereas the EuroQol and SF tools require the purchase of a license, an equivalent Veterans SF‐12 (VR‐12), is freely available for noncommercial use 29. Considering the widespread use of both EQ‐5D and SF‐12/VR‐12 in existing orthopedic registries and the absence of major advantages of one over the other, the working group agreed to recommend use of either tool for HRQOL evaluation. For comparisons, a cross‐walk algorithm is available to convert SF‐12 responses into an EQ‐5D index score 30.

Work status

The standard ICHOM question for evaluating work status was recommended 31. The exact question and response options are shown in Table 1. Comparing responses to this question at baseline and regular followup intervals will reveal the impact of OA on a patient's ability to work over time.

Satisfaction

In addition to measuring health status directly, there are other useful patient‐reported measures of treatment success, such as satisfaction, fulfillment of expectations, and willingness to repeat or to recommend treatment to others. Although such measures are not true PROMs, they are clearly associated with changes in PROM scores and may indicate how well a provider manages to engage the patient in shared decision‐making and to set realistic expectations on outcomes 32. As nonsurgical and surgical treatments differ in their effectiveness and risk profiles, the working group agreed on overall satisfaction with treatment results as a common outcome domain for evaluating all treatments 33.

Complications and adverse events

The working group considered different approaches for measuring complications and adverse events of surgical treatments. In the absence of uniform, internationally applicable definitions for such events, the working group recommended the commonly used all‐cause 30‐day readmission and all‐cause 30‐day mortality following surgical intervention 34. In addition, any complication requiring return to theater for a consecutive surgery (whether major or minor and regardless of when it occurred) was considered a reoperation and must be recorded. Due to the diversity of nonsurgical OA treatments and the lack of specificity of potential complications, we did not consider it feasible to measure complications and adverse events associated with nonsurgical care in this Standard Set.

Disease progression measures

As the natural course of OA is chronic and progressive, the working group felt that it was important to include measures that indicate disease progression and developed 2 questions to capture this outcome (Table 1). These questions ask which treatments the patient has undergone and which care providers the patient has consulted for their hip or knee problems in the past year. Annual measurement will reveal intensifications of treatment, indicating disease progression. The validity and utility of these questions will be evaluated following the collection of pilot data, and necessary changes will be made.

Case‐mix factors

A number of patient characteristics and risk factors are known to influence the outcomes shown in Table 1. To ensure fair comparisons across providers with diverse patient populations, the working group identified and defined key adjustment measures to include in the Standard Set. We sought internationally valid measures that minimized the burden of data collection on both patients and health care providers. As described above for the selection of outcome measures, the working group first agreed on the risk factor domains to be included and then selected definitions for measuring these domains. Selected domains were patient demographics, body habitus, lifestyle factors, joint related factors, and comorbidities. Table 2 shows a complete list of the risk adjustment measures with the percentage of working group members who agreed on their inclusion.

Table 2.

Case‐mix variable domains and definitions included in the Standard Set

| Category and case‐mix factor domain | Case‐mix factor definition | Agreementa |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | Date of birth | 100 |

| Sex | Sex at birth | 100 |

| Education level | Please indicate the highest level of schooling completed: none, primary, secondary, tertiary (university or equivalent) | 88 |

| Baseline clinical status | ||

| Joint‐specific history | Please indicate if the patient has a history or findings of any of the following for each hip and knee: none; trauma or ligmental injury; congenital or developmental disorders; other joint disorders including but not limited to osteonecrosis, inflammatory arthritis, gouty arthritis, septic arthritis, and Paget's disease of the bone | 84 |

| Joint‐specific surgical history | Please indicate the type of surgery the patient has on each hip and knee: none; joint replacement; osteotomy; osteosynthesis/facture surgery; ligament reconstruction (knee only); other arthroscopic procedures | 82 |

| Other case‐mix factors | ||

| Living status | Which statement best describes your living arrangement? I live with partner/spouse/family/friends; I live alone; I live in a nursing home/hospital/other long‐term care home; other | 100 |

| Body mass index | Calculated from patient‐reported height and weight | 88 |

| Physical activity | In a typical week, how much time do you spend doing physical activity? Physical activity is any activity that makes you breathe hard, feel warm, and feel your heart beat faster. Examples of physical activity are walking, bicycling, and dancing and also housecleaning and gardening. None; about 30 minutes; about 1 hour; about 2 hours; more than 2 hours | 88 |

| Tobacco smoking status | Do you smoke? No/yes | 88 |

| Comorbid conditions | Have you been told by a doctor that you have any of the following? (Tick all that apply to you) Heart disease (for example angina, heart attack, or heart failure); high blood pressure; problems caused by a stroke; leg pain when walking due to poor circulation; lung disease (for example asthma, chronic bronchitis, or emphysema); diabetes mellitus; kidney disease; diseases of the nervous system (for example Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis); liver disease; cancer (within the last 5 years); depression; arthritis in your back or other condition affecting your spine; rheumatoid arthritis or another kind of arthritis in addition to osteoarthritis | 92 |

Percentage agreement among survey respondents.

Demographics, body habitus, and lifestyle factors

The key demographic factors considered important to include in the Standard Set were patient age, sex, and socioeconomic status 35, 36, 37. Although many different indicators of socioeconomic status have been published in the literature, only education level as defined by the International Standard Classification of Education can be considered consistent across countries and cultures for international use 36, 38. The working group also identified body mass index, smoking status, and living condition as having a potentially important influence on outcomes and relevant for inclusion in the Standard Set 39.

Although physical activity was considered an important factor affecting treatment outcomes, an appropriate and feasible measure could not be identified. Therefore, the working group adapted a question from the Better Management of Patients with Osteoarthritis Registry in Sweden to create the question shown in Table 2. The working group recommends but does not require the use of this newly developed question. The validity of this question will be tested and its formal inclusion in the Standard Set determined in time.

Joint history

The diversity of symptoms and clinical presentations of OA as well as its multifactorial etiology suggest that OA is a heterogeneous group of disorders with a common structural end point 40. Unfortunately, despite a large body of research, there is no commonly accepted system for classifying OA phenotypes 41. As specific disease history and etiology may influence disease progression and outcome of treatment, in the absence of an existing, robust classification system, the working group developed a simple physician‐reported measure of joint history that broadly categorizes OA etiologies (Table 2). A similar physician‐reported measure of joint‐specific previous surgical history was also included in the set. Physicians are asked to report these measures for all 4 joints, as multiple joint involvement affects outcomes 42.

Comorbidity status

Comorbidities are known to affect outcomes following joint replacement surgery 43. Although there is limited research on the effects of comorbidities on nonsurgical OA treatments, they likely also affect these outcomes and, in some cases, the available treatment options. Therefore, there was strong consensus within the working group on the importance of including a measure of comorbidities, regardless of treatment modality.

Although well‐established systems for classifying comorbidity status from clinical or administrative data exist, these systems were not considered feasible for inclusion in the Standard Set due to wide variation in how such information is recorded across countries and health care systems. A 13‐item patient‐reported comorbidity index has proven feasible and useful for risk stratification in the UK's National Health Service (NHS) audit for joint replacements 44. It is a simplified version of the Self‐Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire developed by Katz et al, which has been shown to have strong correlation with measures derived from administrative data 45, 46. The index used by the NHS was modified for inclusion in the Standard Set to include a measure of spinal disease and inflammatory arthritis 47. Finally, PROMs measured at baseline provide relevant information about patients’ baseline wellbeing and may also be used in risk stratification. For example, the working group recommends using the emotional health components of the SF‐12, VR‐12, or EQ‐5D to adjust for baseline mental health status.

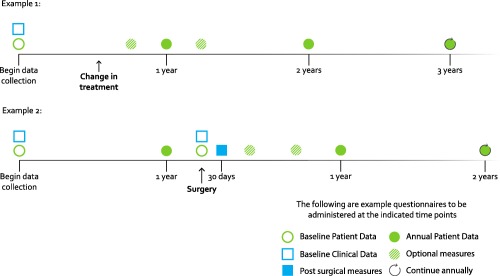

Data collection timeline

The Standard Set includes a recommendation for the timing of data collection, which is shown in Figure 1. Outcomes and case‐mix variables were categorized into baseline and annual measures. All patient‐reported measures are to be collected at baseline and information about disease etiology and previous surgeries are collected at baseline via physician report or abstraction from clinical records. Annual measures include pain, functional status, HRQOL, and all nondemographic case‐mix variables. Data collection may begin at diagnosis of OA, at referral for surgery, or following other major changes in treatment regime. Presurgery baseline measures may be collected at any time within a 3‐month window preceding the date of surgery. Once data collection begins, it continues annually for life or as long as feasible given the constraints of the local health care system. In the event that a patient has surgery to treat hip or knee OA after the start of data collection, the data collection timeline is reset by this event.

Figure 1.

Data collection timeline.

Importantly, all annual measures are patient‐reported. This model has been successfully deployed in recent total joint replacement registry efforts 48, 49, 50 and facilitates implementation by enabling data capture outside the context of clinical care, as data collection may not correspond with the timing of patient clinic visits. Physician‐reported measures are only required at baseline or prior to surgery, which correspond to clinic visits.

Although annual measures were considered most appropriate for comparing outcomes across providers, the working group also recognized the value of tracking patient‐reported outcomes in clinical practice to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments and aid in shared decision‐making. Therefore, a smaller set of optional patient‐reported measures (pain and functional status) are recommended for use in clinical practice, with the timing of data collection for these measures left to the care provider's discretion.

DISCUSSION

The ICHOM working group on hip and knee osteoarthritis defined a set of patient‐centered outcome measures intended for evaluating the treatment of hip and knee OA and facilitating international comparisons, shared learning, and benchmarking on value across health care systems. The main outcomes assessed by the Standard Set include joint pain, physical functioning, HRQOL, work status, mortality, reoperations, readmissions, and overall satisfaction with treatment results. In addition, a set of case‐mix variables was defined to enable adjusted comparisons across different populations, health care providers, or health systems. Baseline data collection with annual followup is recommended for comparing outcomes across providers. An optional set of measures is recommended but not required for use in clinical practice.

This set of measures focuses on patients with hip or knee OA, regardless of disease severity, treatment, or type of provider. In doing so, it enables continuous assessment over the entire course of the disease in alignment with the fundamental framework of value‐based health care delivery 51. Although this approach may currently present an implementation challenge, we hope it stimulates providers from different settings to coordinate their activities around the patient as opposed to conducting isolated interventions, creating consistency over the full continuum of care.

Traditionally, joint replacement registries commonly organize data collection by primary intervention, joint, and laterality (each joint subject to a primary intervention yields a new case). This approach is suitable for implant surveillance and procedure‐related outcomes studies but is inappropriate for evaluating condition‐ and patient‐centered outcomes in patients with more than 1 affected joint. Patients with OA will commonly require symptomatic treatment for more than 1 knee and hip, so that primary treatment outcomes such as function and work status are affected by the total burden of the condition. Therefore, adoption of the condition‐ and patient‐centered approach to outcomes measurement recommended here may require restructuring of current databases 48. We believe, however, that registries that invest in these changes will gain richer data sets for optimizing joint replacement outcomes.

The Standard Set is publicly available and was designed to be implemented in a variety of settings. Individual provider organizations and registries around the world are encouraged to implement or align with the Standard Set, with ICHOM working to facilitate the development of the infrastructure to share and compare results.

Particularly in countries without a government‐run health system or centralized documentation, patients’ clinical data may be fragmented across several health records due to changes in providers or insurers or treatment by multiple providers (e.g., physiotherapists, surgeons, and primary care physicians). The working group was cognizant of this issue when structuring the data collection. For patients receiving nonsurgical treatment, 90% of the measures included in the Standard Set are patient‐reported. Surgery requires the collection of 3 additional measures. However, with the exception of adverse events following surgery, all clinical measures are captured at baseline or presurgical assessment when patients are routinely evaluated in the clinic. Furthermore, all annual followup measures are patient reported. This procedure allows for direct data collection from patients, alleviating the need to track records across providers. We recommend that providers and registries begin collecting these measures over as much of the care continuum as currently feasible, with the goal of increasing care coordination and broadening data collection as the necessary infrastructure evolves.

We aimed to develop a core set of outcome measures appropriate for evaluating care across countries and clinical settings. To that end, the working group included representatives from 5 continents, 10 countries, and a range of clinical specialties. A similarly well‐balanced steering committee, comprised of 8 members of the original working group, has been established to govern the Standard Set and oversee updates or changes over time.

In conclusion, we believe this Standard Set provides meaningful, comparable, and easy to interpret measures that are ready to implement in clinics and/or registries globally. This single set of case‐mix and outcome measures allows comparisons of outcomes across the full continuum of hip and knee OA care, facilitating communication across providers and comparisons across treatment modalities. This knowledge will incentivize and empower providers to improve care, as well as allow patients, providers, and payers to make informed decisions about their health care spending and treatment options. These are crucial ingredients in a value‐based health care system that will benefit all involved parties through transparency and well‐aligned incentives.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Dr. Rolfson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Rolfson, Wissig, van Maasakkers, Stowell, Franklin.

Acquisition of data. Rolfson, Wissig, Franklin.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Rolfson, Wissig, Ackerman, Ayers, Barber, Benzakour, Bozic, Budhiparama, Caillouette, Conaghan, Dahlberg, Dunn, Grady‐Benson, Ibrahim, Lewis, Malchau, Manzary, March, Nassif, Nelissen, Smith, Franklin.

Supporting information

Supplementary Appendix A

Supported by the Hoag Orthopedic Institute, the Connecticut Joint Replacement Institute, and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

Dr. Budhiparama sits on the advisory boards of DePuy Synthes, Roche, and Sanofi Aventis and has received grants from Zimmer Biomet (less than $10,000). Dr. Malchau has received institutional grants from DePuy Synthes and Zimmer Biomet (more than $10,000 each) and is a board member and shareholder in RSA Biomedical.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Statistics 2013 . World Health Organization; 2013. URL: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2013_Full.pdf.

- 2. World Health Organization . World health report 2010. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. URL: http://www.who.int/entity/whr/2010/whr10_en.pdf?ua=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating value‐based competition on results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maetzel A, Li LC, Pencharz J, Tomlinson G, Bombardier C, Community H, et al. The economic burden associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypertension: a comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Roemer F, Zhang Y, Neogi T. Structural correlates of pain in joints with osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma‐Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non‐surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorstensson CA, Garellick G, Rystedt H, Dahlberg LE. Better management of patients with osteoarthritis: development and nationwide implementation of an evidence‐based supported osteoarthritis self‐management programme. Musculoskeletal Care 2015;13:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Herberts P, Malchau H. Long‐term registration has improved the quality of hip replacement: a review of the Swedish THR Register comparing 160,000 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 2000;71:111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Furnes O. Improved results of primary total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2010;81:649–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM, Abbott JH, Stratford P, Davis AM, et al. OARSI recommended performance‐based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1042–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pham T, Van Der Heijde D, Lassere M, Altman RD, Anderson JJ, Bellamy N, et al. Outcome variables for osteoarthritis clinical trials: the OMERACT‐OARSI set of responder criteria. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1648–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pill J. The Delphi method: substance, context, a critique and an annotated bibliography. Socioeconomic Plann Sci 1971;5:57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G, Bierma‐Zeinstra MA, Arden NK, Bresnihan B, et al. EULAR evidence‐based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McConnell S, Kolopack P, Davis AM. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC): a review of its utility and measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;80:63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): development of a self‐administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998;28:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klassbo M, Roos EM. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS): validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003;4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perruccio AV, Stefan Lohmander L, Canizares M, Tennant A, Hawker GA, Conaghan PG, et al. The development of a short measure of physical function for knee OA KOOS–Physical Function Shortform (KOOS‐PS): an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:542–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis AM, Perruccio AV, Canizares M, Tennant A, Hawker GA, Conaghan PG, et al. The development of a short measure of physical function for hip OA HOOS–Physical Function Shortform (HOOS‐PS): an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:1073–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36‐item short‐form health survey (SF‐36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kosinski M, Keller SD, Hatoum HT, Kong SX, Ware JE Jr. The SF‐36 Health Survey as a generic outcome measure in clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions and score reliability. Med Care 1999;37 Suppl 5:MS10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rolfson O, Rothwell A, Sedrakyan A, Chenok KE, Bohm E, Bozic KJ, et al. Use of patient‐reported outcomes in the context of different levels of data. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93 Suppl 3:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. EuroQol Group . EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Obradovic M, Lal A, Liedgens H. Validity and responsiveness of EuroQol–5 dimension (EQ‐5D) versus Short Form–6 dimension (SF‐6D) questionnaire in chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.BU School of Public Health. VR‐36, VR‐12 and VR‐6D. URL: http://www.bu.edu/sph/research/research-landing-page/vr-36-vr-12-and-vr-6d/.

- 30. Le QA. Probabilistic mapping of the health status measure SF‐12 onto the health utility measure EQ‐5D using the US‐population‐based scoring models. Qual Life Res 2014;23:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clement RC, Welander A, Stowell C, Cha TD, Chen JL, Davies M, et al. A proposed set of metrics for standardized outcome reporting in the management of low back pain. Acta Orthop 2015;86:523–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hamilton DF, Lane JV, Gaston P, Patton JT, Macdonald D, Simpson AH, et al. What determines patient satisfaction with surgery? A prospective cohort study of 4709 patients following total joint replacement. BMJ Open 2013;3;pii e002525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mancuso CA, Jout J, Salvati EA, Sculco TP. Fulfillment of patients' expectations for total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:2073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fischer C, Lingsma HF, Marang‐van de Mheen PJ, Kringos DS, Klazinga NS, Steyerberg EW. Is the readmission rate a valid quality indicator? A review of the evidence. PloS One 2014;9:e112282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gordon M, Greene M, Frumento P, Rolfson O, Garellick G, Stark A. Age‐ and health‐related quality of life after total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2014;85:244–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greene ME, Rolfson O, Nemes S, Gordon M, Malchau H, Garellick G. Education attainment is associated with patient‐reported outcomes: findings from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1868–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cleveland RJ, Luong ML, Knight JB, Schoster B, Renner JB, Jordan JM, et al. Independent associations of socioeconomic factors with disability and pain in adults with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cleveland RJ, Schwartz TA, Prizer LP, Randolph R, Schoster B, Renner JB, et al. Associations of educational attainment, occupation, and community poverty with hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:954–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jameson SS, Mason JM, Baker PN, Elson DW, Deehan DJ, Reed MR. The impact of body mass index on patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and complications following primary hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1889–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 2005;365:965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F, Lafeber FP. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet 2011;377:2115–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Perruccio AV, Power JD, Evans HM, Mahomed SR, Gandhi R, Mahomed NN, et al. Multiple joint involvement in total knee replacement for osteoarthritis: effects on patient‐reported outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:838–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hunt LP, Ben‐Shlomo Y, Clark EM, Dieppe P, Judge A, MacGregor AJ, et al. 45‐day mortality after 467,779 knee replacements for osteoarthritis from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales: an observational study. Lancet 2014;384:1429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in England: the case‐mix adjustment methodology. Department of Health; 2012. URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216507/dh_133449.pdf.

- 45. Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care 1996;34:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self‐Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ayers DC, Li W, Oatis C, Rosal MC, Franklin PD. Patient‐reported outcomes after total knee replacement vary on the basis of preoperative coexisting disease in the lumbar spine and other nonoperatively treated joints: the need for a musculoskeletal comorbidity index. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:1833–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Franklin PD, Allison JJ, Ayers DC. Beyond joint implant registries: a patient‐centered research consortium for comparative effectiveness in total joint replacement. JAMA 2012;308:1217–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rolfson O, Karrholm J, Dahlberg LE, Garellick G. Patient‐reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: results of a nationwide prospective observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:867–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Department of Health . Guidance on the routine collection of patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) for the NHS in England 2009/10. 2008. URL: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/guidance-on-the-routine-collection-of-patient-reported-outcome-measures-(proms)-(pdf-1184-kb)-nhs-(2008).pdf?sfvrsn=4.

- 51. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010;363:2477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix A