Highlights

-

•

A rare case of huge metallosis is presented.

-

•

If prosthesis brackage is detected, revision surgery should be attempted.

-

•

A regular follow-up after surgery it’s the best way to success.

Keywords: Metallosis, Pseudotumor, Complication, Tumoral prosthesis, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Metallosis is a condition characterized by an infiltration of periprosthetic soft tissues and bone by metallic debris resulting from wear or failure of joint arthroplasties.

Presentation of case

Authors describe a case of a 45-year-old man treated for an osteosarcoma of the distal femur with a modular prosthesis when he was 18 years old, he developed massive metallosis with skin dyspigmentation after 17 years. His medical\surgical history was remarkable for a left tumoral knee prosthesis implanted 21 years ago. Two years before revision, the patient had a car accident with a two-points prosthesis breakage and despite the surgeon’s advice, the patient refused surgery. In two years, prosthesis malfunction caused a progressive catastrophic soft tissues infiltration of metallic debris.

Discussion and conclusion

Authors suggest that if prosthesis fracture is detected, revision surgery should be attempted as earlier as possible.

1. Introduction

Metallosis is an uncommon condition in which there is infiltration of periprosthetic soft tissues and bone by metallic debris resulting from wear of joint arthroplasties. Complications due to metalossis include osteolysis, tissue necrosis and formation of pseudo tumors [1]. The management of metallosis may represent a challenge for the Orthopedic surgeon, due to the variety of presenting symptoms.

We describe a case of severe metallosis in the setting of a tumoral knee prosthesis (TKP) failure presenting with massive soft tissues infiltration and skin dyspigmentation.

2. Presentation of the case

In year 1995, an 18-year-old male patient was operated for a chondroblastic osteosarcoma of the left distal femur knee with an intraarticular resection and a modular prosthesic replacement of the distal femur, after a neo-adjuvant therapy. After surgery following the protocol he underwent also to the adjuvant therapy. At CT-scans the lung were free from metastasis. No perioperative complications were reported; the patient was followed until the 5th year after surgery. At the last follow-up there were no local recurrence of the oncologic disease and the prosthesis showed no signs of mobilization (Fig. 1A). In November 2010 the patient reported a car accident, with a direct trauma to the left lower limb. The X-ray showed a two-point prosthesis breakage (femur and medial tibial plateau) and a femoral stem subsidence (Fig. 1B). However, he was able to walk independently and with moderate pain. Despite surgeon advice, the patient refused revision surgery for personal reasons. In December 2012, the patient returned to the outpatient clinic, with an increasing pain in his left knee and with lower limb length discrepancy. The clinical examination revealed a massive black dyspigmentation of the skin (Fig. 2C), moderate swelling, mild warmth and tenderness. Clinical assessment revealed the left (surgical) leg was 2 cm shorter than the right. The range of motion was 5°–35°,severely decreased compared to previous examinations. Plain X-rays (Fig. 2A–B), that confirmed the lower limb discrepancy, were suspicious for metallosis: presence of radio-dense line (“cloudy sign”), associated with “the bubble sign” described by Su [2] and the “metal-line sign” a thin rim of linear increased density in the suprapatellar pouch region described by Weissman [3].

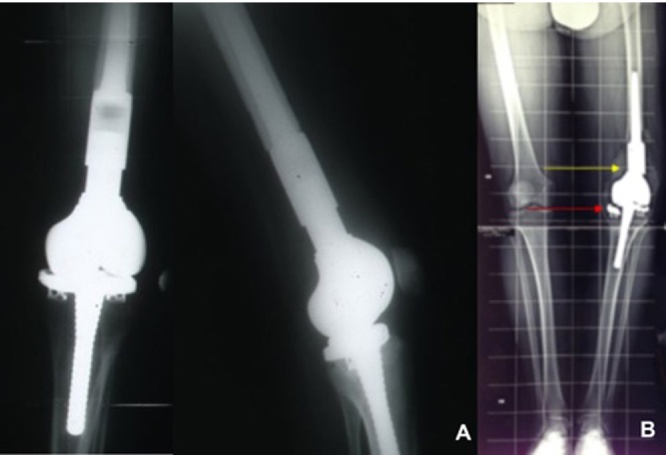

Fig. 1.

(A) Radiographs taken at 5-year follow-up (year 2000) showing a cementless Kotz modular femoral and tibial reconstruction (KMFTR) in an acceptable positioning. (B) An anteroposterior standing radiograph of the lower left limb showing fracturing of the proximal femoral stem (yellow arrow) and medial tibial plateau (red arrow).

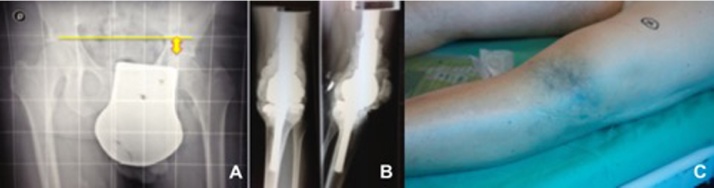

Fig. 2.

(A) Patient presented a large area of cutaneous metallosis characterized by dyspigmentation of the skin overlying the joint space affected. (B) anteroposterior standing radiograph demonstrating dismetry: left (surgical) leg was 2 cm shorter than the right with a deviation in varus of the knee. (C) A-P and L-L X-rays showing the typical amorphous, increased density material defined as “cloud sign” of metallosis.

The laboratory investigations showed leukocyte count = 9600 cell per cubic millimeter, C-reactive protein = 78 mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate = 46 mm/h. The patient accepted surgery and was scheduled for revision of his TKP. In January 2012, the patient was operated in supine position without the use of tourniquet. The TKP was approached through a modified midvastus approach, extended proximally to the femur to allow a soft tissue debridement. Revision knee surgery confirmed the presence of massive soft tissue metallosis of the distal femur and the proximal tibia (Fig. 3A–B). However, there was not osteolysis, both prosthetic stems resulted still well bone-integrated (Fig. 3C–D). The revision surgery was not more difficult than any others revision procedure. It was more difficult to identify anatomic structures due to soft tissue pigmentation. After prosthesis components removal, both femoral and medial tibial plateau fracture were confirmed and an extensive polyethylene wear and deformation distributed asymmetrically over the medial and lateral joint surfaces was detected (Fig. 4).

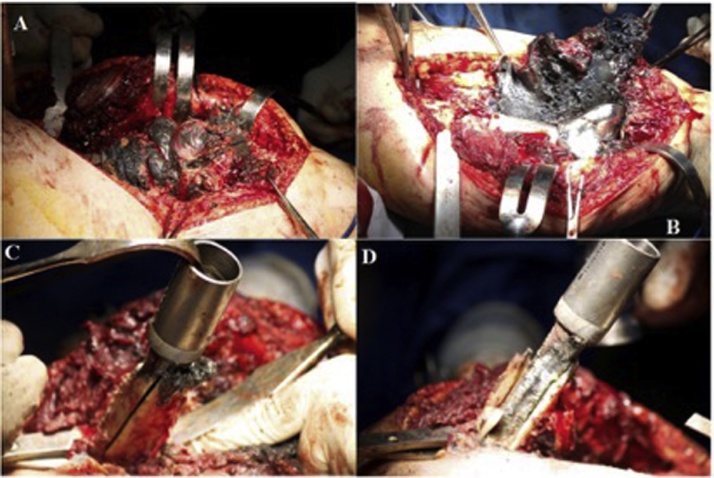

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative photographs show (A–B) massive metallosis of the soft tissue adjacent to the prostheses, and (C–D) absence of osteolytic reaction with the femoral prosthetic stem well integrated to bone.

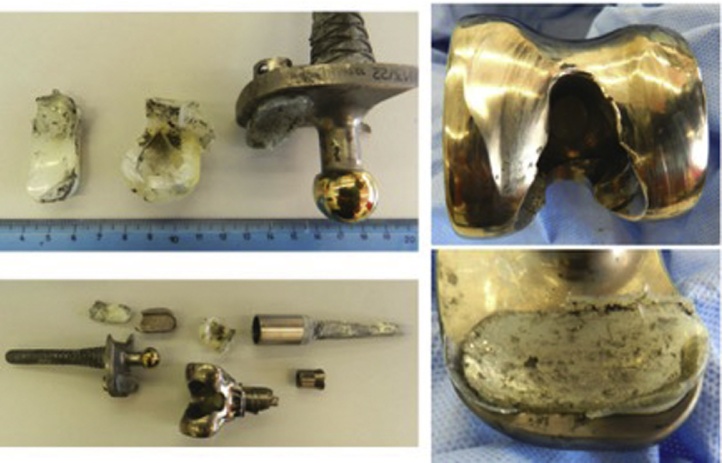

Fig. 4.

Prosthesis after explantation: a femoral stem and medial tibial plateau breakage and extensive polyethylene wear and deformation distributed asymmetrically over the medial and lateral joint surfaces were detected.

During the revision procedure periprosthetic tissue samples were retrieved from the joint neo-capsule, muscular and bony sites. Samples were fixed in 4% buffered formalin for twenty-four hours and subsequently included in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded specimens were sectioned to a thickness of 5 mm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined with a light microscope. Microbiological tests of intraoperative specimens, including cultures and Gram stain, were sterile.

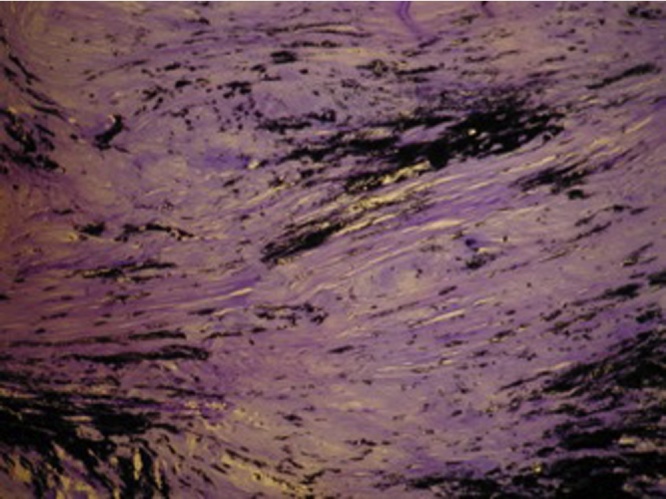

Pathologic examination of the excised tissue showed large areas of bland necrosis surrounded by a reactive fibrosis. Numerous black, irregular, metallic particles aggregates were associated with dense granulomatous reaction. Inflammatory cells were composed predominantly of lymphoplasmacytes showing perivascular aggregates followed by macrophages and eosinophils Specimens were graded as 3+ (jet-black histiocytes/ > 100 visible metal particles/histiocytes) according to the modified Mirra [4] classification for metallosis (Fig. 5). No local relapse of the primary oncologic disease was noted.

Fig. 5.

Extensive metallic particle deposition in the pseudo synovial tissue. H&E × 200.

The patient's recovery was uncomplicated. His rehabilitation included strengthening and a range of motion exercises, which he started on the third postoperative day. The patient was discharged uneventfully after nine days of hospitalization. At the latest follow-up on January 2016 (3 years post-operatively) the patient had a painless and stable knee joint, the ROM achieved was 5° 80°. No clinical or imaging evidence of wear, metallosis or infection were reported, with a normal serum concentration of metal ions. Our patient was informed that data concerning his case would be submitted for publication and he signed a written informed consent.

3. Discussion

The modular uncemented prosthetic reconstruction after resection of tumors of the distal femur has been successfully described in previous studies, with excellent or good clinical results in 75% of patients [5].

Revision of tumor prosthesis of the knee joint due to stem breakage has been previously described in literature [6]. The most common reason for implant failure is aseptic loosening followed by implant fracture and infection [7].

The overall incidence of stem breakage ranges between 0% [8] and 6% [5] at 5 year of follow-up.

Metallosis represent a rare complication after tumoral prosthesis failure secondary to components breakage. It consists in deposition of metallic debris into the periprosthetic soft tissues, involving the joint capsule or cavity, and the extra-articular tissues as described by Willert and Semtilsh [9]. Modular prosthesis for oncologic reconstruction are often silver-coated, shown to be effective against infections [8]. The deposition of silver products in the surrounded soft tissue is known as argyria, that could be a consequence of a silver-coated mega-prosthesis replacement [10]. The body reacts by forming a scar tissue through the “formation of granulation tissue, including macrophages and foreign-body giant cells” [9].

Deposition of debris from the prosthesis into the peri-articular soft tissues can cause pain and systemic effects but can also be symptomless, manifesting only with skin dyspigmentation. Metallosis is most commonly described at the weight bearing joints, but has been reported in other locations such as the shoulder, wrist and elbow [11]. In the event of prosthesis failure, an early revision is strongly recommended. In our case the patient refused surgery and received a delayed revision after 2 years after diagnosis of prosthetic breakage. In that time a catastrophic soft tissues metal deposition occurred. As described in a previous paper by Callender et al. [12], our patient presented a large area of cutaneous metallosis characterized by dyspigmentation of the skin overlying the joint space of the affected limb.

However, nor systemic consequences were present. Patient complained only local symptoms and accepted surgery only because his ROM reduction.

Metallosis has been strongly suspected on radiographs for their typical appearance:

-

1)

periprosthetic soft tissue amorphous densities, referred as “cloud sign”

-

2)

the “metal-line sign,” a thin rim of linear increased density in the suprapatellar pouch region

-

3)

the “bubble sign” a curvilinear radiodensities that outline the joint space.

Revision surgery revealed a massive muscular and soft tissues metal infiltration, despite absence on osteolysis with a well fixed femoral and tibial component (Fig. 3A).

After 3 months of assisted rehabilitation, the patient returned at his normal daily living activities. Serology tests carried out at last follow-up found normal levels of metallic ionemia. Extreme wear and associated metallosis of this kind are rare.

This kind of cases highlight the importance of regular follow-up after surgery. The patient was lost at follow-up and returned just when a wide extension of the wear was visible. We recommend that if prosthesis fracture is detected, revision surgery should be attempted as earlier as possible, where the procedure is less invasive and technically easier.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

We have a consent by the patient. We have not submitted the case to the Ethics Committee approval.

Consent

There are no data enabling identification of the patient.

Author contribution

Luca la Verde – writing the paper.

Domenico Fenga – writing the paper.

Maria Silvia Spinelli – writing the paper.

Francesco Rosario Campo – traduction.

Michela Florio – traduction.

Michele Attilio Rosa – study concept.

Guarantor

Prof. Michele Attilio Rosa.

Contributor Information

Luca La Verde, Email: lucalaverde1@gmail.com.

Domenico Fenga, Email: dfenga@gmail.com.

Maria Silvia Spinelli, Email: msilviaspinelli@yahoo.it.

Francesco Rosario Campo, Email: campofrancescorosario@yahoo.it.

Michela Florio, Email: michelaflorio86@gmail.com.

Michele Attilio Rosa, Email: mattilio51@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Schiavone Panni A., Vasso M., Cerciello S., Maccauro G. Metallosis following knee arthroplasty: a histological and immunohistochemical study. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011;24:711–719. doi: 10.1177/039463201102400317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su E.P., Callander P.W., Salvati E.A. The bubble sign: a new radiographic sign in total hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 2003;18:110–112. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissman B.N., Scott R.D., Brick G.W., Corson J.M. Radiographic detection of metal-induced synovitis as a complication of arthroplasty of the knee. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1991;73:1002–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doorn P.F., Mirra J.M., Campbell P.A., Amstutz H.C. Tissue reaction to metal on metal total hip prostheses. Clin. Orthop. 1996:S187–S205. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capanna R., Morris H.G., Campanacci D., Del Ben M., Campanacci M. Modular uncemented prosthetic reconstruction after resection of tumours of the distal femur. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1994;76:178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida Y., Osaka S., Kojima T., Taniguchi M., Osaka E., Tokuhashi Y. Revision of tumor prosthesis of the knee joint. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. Orthop. Traumatol. 2012;22:387–394. doi: 10.1007/s00590-011-0848-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittermayer F., Krepler P., Dominkus M., Schwameis E., Sluga M., Heinzl H., Kotz R. Long-term followup of uncemented tumor endoprostheses for the lower extremity. Clin. Orthop. 2001:167–177. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200107000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pala E., Trovarelli G., Calabrò T., Angelini A., Abati C.N., Ruggieri P. Survival of modern knee tumor megaprostheses: failures, functional results, and a comparative statistical analysis. Clin. Orthop. 2015;473:891–899. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3699-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willert H.G., Semlitsch M. Reactions of the articular capsule to wear products of artificial joint prostheses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1977;11:157–164. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820110202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karakasli A., Hapa O., Akdeniz O., Havitcioğlu H. Dermal argyria: cutaneous manifestation of a megaprosthesis for distal femoral osteosarcoma. Indian J. Orthop. 2014;48:326–328. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.132528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelstein Y., Ohm H., Rosen Y. Metallosis and pseudotumor after failed ORIF of a humeral fracture. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2011;69:188–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callender V.D., Cardwell L.A., Munhutu M.N., Bigby U., Rodney I.J. Cutaneous metallosis in patient with knee prosthesis composed of cobalt-chromium molybdenum alloy and titanium-aluminum-vanadium alloy. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]