Abstract

Paclitaxel is a standard second‐line gastric cancer treatment in Japan. Trastuzumab could be active as second‐line chemotherapy for taxane/trastuzumab‐naïve patients with epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2)‐positive advanced gastric cancer. Patients aged ≥20 years with HER2‐positive, previously treated (except for trastuzumab and taxane), unresectable or recurrent gastric adenocarcinoma underwent combined trastuzumab (first and subsequent doses of 8 and 6 mg kg−1, respectively, every 3 weeks) and paclitaxel (days 1, 8, 15, every 4 weeks) treatment. Study endpoints were best overall response, progression‐free survival, overall survival, and safety. From September 2011 to March 2012, 47 Japanese patients were enrolled. Forty patients discontinued treatment after a median of 128.5 (range 4–486) days. Complete and partial responses were obtained in one and 16 patients (response rate of 37% [95% CI 23–52]), respectively. Median progression‐free survival and overall survival were 5.1 (95% CI 3.8–6.5) and 17.1 (95% CI 13.5–18.6) months, respectively. Grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia (32.6%), leukopenia (17.4%), anemia (15.2%) and hypoalbuminemia (8.7%). There was no clinically significant cardiotoxicity or cumulative toxicity. Three (disturbed consciousness, pulmonary fibrosis, and rapid disease progression) grade 5 events occurred. In conclusion, trastuzumab combined with paclitaxel was well tolerated and was a promising regimen for patients with HER2‐positive, previously treated, advanced or recurrent gastric cancer.

Keywords: human epidermal growth factor receptor, paclitaxel, recurrence, stomach neoplasms, trastuzumab

Short abstract

What's new?

Second‐line chemotherapy can provide important survival benefits in patients with advanced or recurrent gastric cancer, and trastuzumab, a HER2‐targeting monoclonal antibody, could be especially useful in second‐line therapy, though its safety and effectiveness are yet to be fully explored. Here, combined trastuzumab‐paclitaxel therapy was assessed in Japanese patients with salvage line HER2‐positive advanced/recurrent gastric cancer. Trastuzumab‐naïve HER2‐positive patients showed high response rates and experienced prolonged survival on the trastuzumab plus paclitaxel regimen. The combination also was generally well tolerated. The findings indicate that HER2‐positive patients treated with paclitaxel can benefit further from the addition of trastuzumab.

Gastric cancer is the second most common cause of cancer‐related death worldwide.1 Combined administration of fluoropyrimidine and a platinum agent is the standard first‐line chemotherapy for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer, while triplet chemotherapy using docetaxel, cisplatin, fluorouracil (DCF); epirubicin, cisplatin, fluorouracil (ECF); or epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine (EOX), are other treatment options.2, 3 In Japan, a combination of S‐1 and cisplatin is considered to be the most prevalent chemotherapy regimen4 for the first‐line treatment. However, most patients experience disease progression during or immediately after first‐line chemotherapy and cannot be cured.

In an adjuvant setting, S‐1 monotherapy has been implemented as the standard treatment of care after curative gastrectomy for stage II and III gastric cancer patients in Japan.5 However, almost half of such patients eventually experience disease relapse and their long‐term prognosis is unfavorable.6 Some patients relapse during or soon after the adjuvant chemotherapy, and fluorinated pyrimidine treatment for those cases, has not necessarily been effective. In this regard, effective treatment options still needed to be investigated for patients after early relapse and after failure of the first‐line chemotherapy.

Recently, randomized studies showed that second‐line chemotherapy with irinotecan or docetaxel monotherapy was able to provide a survival benefit for patients with advanced gastric cancer after failure of the first‐line chemotherapy.7, 8, 9 Because the WJOG 4007 trial showed that weekly paclitaxel provided equivalent effectiveness to irinotecan, weekly paclitaxel has been recognized to have an important role in the second‐line chemotherapy,10 and is utilized as one of the most common regimens for advance gastric cancers.11, 12

The global, randomized, phase III trastuzumab for gastric cancer (ToGA) study showed that first‐line treatment with trastuzumab combined with capecitabine/fluorouracil and cisplatin improved overall survival (OS) in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)‐positive advanced or recurrent gastric cancer.13 However, not all of these patients receive trastuzumab as part of the first‐line chemotherapy. Furthermore, the utility of trastuzumab as an adjuvant therapy has not yet been fully established to date. Additionally, the benefits of existing second‐line treatments are modest at best, claiming further development of alternative second‐line options. Thus, there is still need to investigate and examine the effectiveness of trastuzumab in second‐line chemotherapy for treating patients with HER2‐positive advanced or early recurrent gastric cancer.

In this regard, the objectives of this study were to estimate the effectiveness and safety of trastuzumab in combination with paclitaxel in trastuzumab‐naïve patients with previously treated, HER2‐positive gastric cancer.

Methods

Eligibility

Patients aged ≥20 years at the time of informed consent were eligible for the study if they had HER2‐positive, histologically confirmed, unresectable or recurrent gastric adenocarcinoma. HER2 status was assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and was judged to be positive in cases of (i) IHC score 3+, or (ii) IHC score 2+ and FISH‐positive. Other inclusion criteria were as follows: one or more prior chemotherapy regimens for advanced/recurrent disease (adjuvant chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine derivative was counted as a prior chemotherapy regimen for recurrence during or within 6 months after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy); last dose of anticancer drug in the prior chemotherapy ≥14 days before enrollment; no previous use of trastuzumab or taxane; presence of measurable lesion(s) according to response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) version 1.0; eastern cooperative oncology group performance status (PS) of 0–2; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥50% (measured by echocardiography or multigated acquisition scan within 28 days before enrollment); and adequate organ function. For the purpose of this study, recurrence within 6 months after completion of chemotherapy was considered as no response, necessitating salvage chemotherapy, an eligibility criterion adopted in several prior studies.7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14 We adopted RECIST version 1.0 rather than version 1.1 to assess measurable lesions and the antitumor effects, as in prior studies,10, 11 to allow direct comparisons with these studies. Exclusion criteria were: active second primary malignancy; severe or uncontrolled concurrent disease; overt infection or inflammation; psychiatric disorder being treated or requiring an antipsychotic therapy; grade ≥2 neuropathy based on common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.0; pericardial effusion, or pleural effusion or ascites requiring drainage; hypersensitivity to drugs formulated with polyoxyethylene castor oil; being treated with disulfiram, cyanamide, carmofur or procarbazine hydrochloride; and pregnant or lactating females, or females wishing to become pregnant. All eligible patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Treatment

Trastuzumab was administered every 3 weeks by intravenous infusion. Its initial dose was 8 mg kg−1 and the subsequent doses were 6 mg kg−1. After the first dose, trastuzumab could only be administered if LVEF ≥40% and the reduction in LVEF (if any) was <10% compared with the baseline value. LVEF was to be measured by echocardiography or multigated acquisition scan within 3 months ± 2 weeks before the next scheduled dose. Trastuzumab was discontinued in patients with grade ≥3 allergic reactions, anaphylactic reactions or infusion reactions.

Paclitaxel (80 mg m−2) was administered via intravenous infusion over 60 min once weekly for 3 weeks followed by a 1‐week rest, repeated every 4 weeks if the following criteria were met: PS ≤2; neutrophil count ≥1,000 mm3; platelet count ≥50,000 mm3; serum bilirubin ≤2.0 mg dL−1; stomatitis, nausea, and vomiting of grade ≤1; other nonhematological toxicities (including neurological disorders, arthralgia, and myalgia) of grade ≤2; and the absence of infection‐related pyrexia of ≥38°C. Subsequent doses of paclitaxel were delayed for ≥1 week in patients with any of the following: PS >2; neutrophil count <1,000 mm3; platelet count <50,000 mm3; serum bilirubin >2.0 mg dL−1; stomatitis, nausea and vomiting of grade >1; other nonhematological toxicities (neurological disorders, arthralgia and myalgia) of grade >2; and absence of infection‐related pyrexia <38°C. The paclitaxel dose could be resumed once these events had resolved and once the neutrophil and platelet counts had increased to ≥1,500 mm3 and ≥75,000 mm3, respectively. If the paclitaxel dose was delayed repeatedly because of adverse events, the dose could be reduced by two levels at the investigator's discretion. The paclitaxel dose could not be increased after a dose reduction. If the dose was decreased to <50 mg m−2, it was considered to be poorly tolerated and the treatment was to be discontinued.

When paclitaxel was administered on the same day as trastuzumab, paclitaxel infusion was started 30 min after completing trastuzumab infusion. Premedication was allowed in accordance with the package insert for paclitaxel to prevent hypersensitivity reactions. Paclitaxel was discontinued if three or more episodes of the following adverse events occurred: febrile neutropenia, grade 4 neutropenia, grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia or the same grade ≥3 nonhematologic adverse events; grade ≥3 allergic reaction or anaphylaxis; or grade 4 nonhematologic adverse events.

Treatments were discontinued at the following events: progressive disease (PD) based on RECIST version 1.0 or clinically determined progression of the primary disease; conversion to resectable; unacceptable adverse event; the patient's refusal to continue treatment; death; delay of the administration of paclitaxel >28 days.

Evaluation

At baseline, the patients' general characteristics and medical history were reviewed, including diagnosis and macroscopic/histologic classification of gastric cancer, imaging to identify measurable lesions, assessment of subjective and objective symptoms, and laboratory tests. Tumor responses were classified using RECIST version 1.0 as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or PD, and were confirmed by the investigators.

Adverse events were evaluated using the CTCAE version 4.0, except for cardiac failure, which was assessed according to the New York Heart Association classification system. Cardiac function was tested every 3 months ± 2 weeks after the baseline measurement, or more frequently if required. Contrast‐enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and plain chest X‐rays were performed within 28 days before enrollment and repeated every 4 weeks after starting treatment, or every 6 weeks from Week 16 onwards. During treatment, laboratory tests (hematology and blood chemistry) were performed on the day before or the day of paclitaxel infusion.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint was the best overall response rate (ORR), which was calculated as the best response in terms of CR + PR at any evaluation time. Secondary endpoints were progression‐free survival (PFS), time to treatment failure (TTF), OS and the incidence and severity of adverse events. Because the ORR for single‐agent taxanes ranges from 15% to 20% in second‐ and later‐line advanced or recurrent gastric cancer, the threshold ORR was set at 15%. The addition of trastuzumab to paclitaxel was expected to increase the ORR by 15%. At a one‐sided significance of 5% and a power of 80%, 47 patients were required for this study. According to the statistical analysis plan, PFS, OS, TTF and safety were to be analyzed in all eligible patients.

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Studies of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The study was approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees at all of the participating centers. The study was registered on the University Hospital Medical Information Network (identifier: UMIN000006223).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between September 2011 and March 2012, 47 patients were enrolled from 35 institutions in Japan. Forty‐seven patients received the protocol treatment. One patient with inadequate organ function was ineligible; therefore, 46 patients were included in the final analyses. The characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Of 46 evaluable patients, six continued treatment at the data cut off (April 15, 2013), and 40 patients discontinued treatment after a median of 128.5 days (range 4–486 days) because of PD (N = 36, 78%), a grade 5 adverse event (N = 2, 4%), investigator's decision based on an adverse event (N = 1, 2%), or administration delayed by >28 days (N = 1, 2%). The administration of paclitaxel was interrupted in 8/46 patients, delayed in 13 patients, and its dose was reduced in 15 patients. There were no interruptions or dose reductions for trastuzumab. Six patients discontinued within 60 days after starting the study. The reasons for discontinuation were PD in three patients, an adverse event in two patients, and the investigator's decision based on an adverse event in one patient.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 37 | 80 |

| Female | 9 | 20 | |

| Age, years | Median (range) | 69 (32–89) | |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 35 | 76 |

| 1 | 10 | 22 | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| HER2 status | IHC3+ and FISH positive | 9 | 20 |

| IHC3+ and FISH unknown | 24 | 52 | |

| IHC2+ and FISH positive | 13 | 28 | |

| Diagnosis status | Advanced | 24 | 52 |

| Recurrence | 22 | 48 | |

| Disease status | Second‐line therapy for advanced disease | 29 | 63 |

| Third‐line therapy for advanced disease | 5 | 11 | |

| Rapid relapse during/after adjuvant chemotherapy | 12 | 26 | |

| Histological typea | Intestinal | 37 | 80 |

| Diffuse | 8 | 17 | |

| Other | 1 | 2 | |

| Gastrectomy | No | 21 | 46 |

| Yes | 25 | 54 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | No | 23 | 92 |

| Yes | 2 | 8 | |

| Site of metastasis | Liver | 25 | 54 |

| Lung | 3 | 7 | |

| Lymph node | 34 | 74 | |

| Peritoneal | 12 | 26 | |

| Bone | 4 | 9 | |

| Other | 3 | 7 | |

| Number of prior treatmentsb | 1 | 39 | 85 |

| 2 | 5 | 11 | |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | No | 30 | 65 |

| Yes | 16 | 35 | |

| Prior treatment with a platinum‐containing regimen | No | 18 | 39 |

| Yes | 28 | 61 | |

Intestinal: pap, tub1, tub2, por1 (macroscopic type 1, 2); diffuse: por1 (macroscopic type 0, 3, 4) por2, sig, muc; other: por (unexplained).

Adjuvant chemotherapy was considered as a first‐line treatment.

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS: performance status; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IHC: immunohistochemistry; FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Tumor responses

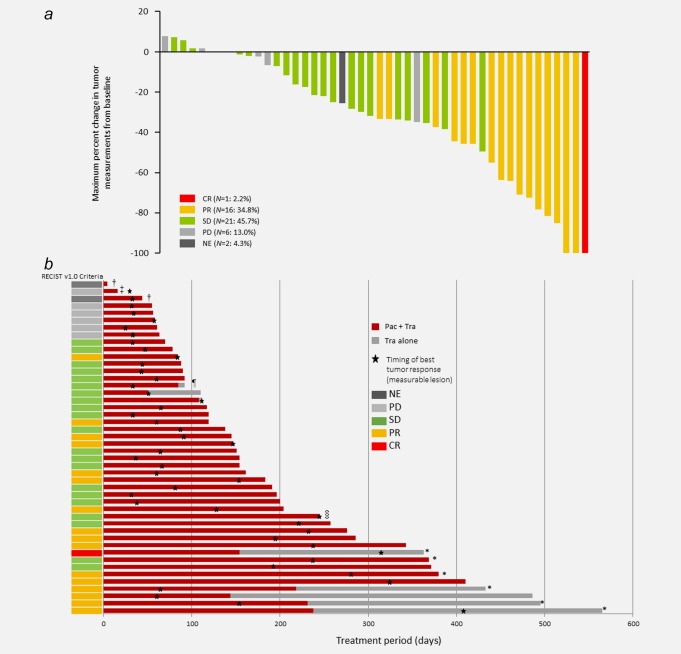

The best overall response was CR in 1 (2.2%), PR in 16 (34.8%), SD in 21 (45.7%), and PD in 6 (13.0%) patients. Overall response was not evaluable in 2 (4.3%) patients, who died before the first or second evaluation. Therefore, the ORR was 37% (95% confidence interval [CI] 23–52%; N = 17/46). Waterfall plots for overall response and time to best overall response are shown in Figures 1a and 1b, respectively. These plots exclude one nonevaluable patient who died before the first examination.

Figure 1.

Waterfall plots of the best overall tumor response (a), and time to best overall tumor response (b) in individual patients. In accordance with RECIST version 1.0, tumor responses were classified in terms of measureable target and nontarget lesions, as well as tumor makers. The best response and maximum change in tumor size were not necessarily assessed at the same times. The patient with NE died before the second on‐treatment examination, so was classified as NE because the study endpoint could not be evaluated at this time. This figure excludes one patient (NE) who died before the first on‐treatment examination. CR: complete response; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; PD: progressive disease; NE: not evaluable; Pac: paclitaxel; Tra: trastuzumab. †Protocol discontinuation criteria (Grade 5 AE), ‡investigator's decision (Grade 2 AE), ¶subsequent treatment delayed, §other reason, *continued therapy. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Survival

The median PFS was 5.1 months (95% CI 3.8–6.5), and ranged from 0.4 to 18.8 months (Fig. 2a). Median OS was 17.1 months (95% CI 13.5–18.6), and ranged from 0.4 to 18.8 months (Fig. 2b). TTF was 5.1 months (95% CI 3.7–6.5), and ranged from 0.4 to 18.8 months.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots of progression‐free survival (a) and overall survival (b). *Brookmeyer and Crowley method.

Disease outcomes in subgroups of patients

The ORR, OS and PFS were also determined in subgroups of patients divided by disease status (recurrent vs. advanced cancer), treatment with vs. without CDDP, and histological subtype (Lauren class: intestinal vs. diffuse/other).

In patients with recurrent cancer (N = 22) and patients with advanced cancer (N = 24), the ORRs were 50% (N = 11) and 25% (N = 6), respectively (p = 0.126). The median OS (18.65 vs. 11.68 months; log‐rank p = 0.0008) and the median PFS (6.67 vs. 3.92 months; log‐rank p = 0.0137) were both significantly longer in patients with recurrent cancer.

In patients treated without CDDP (N = 22) or with CDDP (N = 24), the ORRs were 36% (N = 8) and 38% (N = 9), respectively (p = 1.000). The median OS (16.81 vs. 16.08 months; log‐rank p = 0.4134) and the median PFS (5.09 vs. 4.53 months; log‐rank p = 0.6807) were similar in both subgroups of patients.

In patients with the intestinal histological subtype (N = 37) and patients with diffuse/other histological subtypes (N = 9), the ORRs were 43% (N = 16) and 11% (N = 1), respectively (p = 0.167). The median OS (16.81 vs. 17.13 months; log‐rank p = 0.40) and the median PFS (5.07 vs. 5.11 months; log‐rank p = 0.34) were similar in both subgroups.

Adverse events

The incidence of grade 3/4 adverse events was low (Table 2). There was no evidence of clinically significant cardiotoxicity or cumulative toxicity. There were three grade 5 events, which included disturbed consciousness on Day 5 (unknown causality) in one patient, pulmonary fibrosis on Day 45 (definitely related to paclitaxel and/or trastuzumab) in one patient, and acute worsening of the primary disease that occurred 22 days after treatment discontinuation (unrelated to the treatment protocol) in one patient. The most common grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia in 15 patients (32.6%), leukopenia in eight patients (17.4%), anemia in seven patients (15.2%) and hypoalbuminemia in six patients (8.7%). Other grade 3/4 events that occurred in ≤3 patients (≤6.5%) included aspartate aminotransferase increased, alanine aminotransferase increased, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, peripheral sensory neuropathy and fatigue.

Table 2.

Adverse events (N = 46).

| Grade 1–5 | Grade ≥3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events | N | % | N | % | |

| Laboratory examinations | Leukopenia | 35 | 76.1 | 8 | 17.4 |

| Neutropenia | 31 | 67.4 | 15 | 32.6 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| AST increased | 22 | 47.8 | 3 | 6.5 | |

| ALT increased | 18 | 39.1 | 2 | 4.3 | |

| ALP increased | 22 | 47.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hyponatremia | 12 | 26.1 | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Hypernatremia | 2 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hypokalemia | 5 | 10.9 | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Hyperkalemia | 16 | 34.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Total bilirubin increased | 4 | 8.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Serum creatinine increased | 8 | 17.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 27 | 58.7 | 4 | 8.7 | |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Anemia | 23 | 50.0 | 7 | 15.2 | |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | Anorexia | 20 | 43.5 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | Nausea | 15 | 32.6 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 4.3 | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Oral mucositis | 8 | 17.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Abdominal pains | 5 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Nervous system disorders | Peripheral motor neuropathy | 8 | 17.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 29 | 63.0 | 3 | 6.5 | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Arthralgia | 4 | 8.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Myalgia | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Fatigue | 28 | 60.9 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Edematous limbs | 10 | 21.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Infusion reactions | 4 | 8.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Immune system disorders | Allergen reaction | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Heart failure | Cardiac failure (NYHA) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Respiratory disorders | Pulmonary fibrosis | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.2 |

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

In subgroups of patients divided by disease status (recurrent vs. unresectable cancer), treatment with/without CDDP, and histological subtype (Lauren class: intestinal vs. diffuse/other), the incidence of adverse events (grade ≥3) was lower in patients with recurrent cancer (N = 11, 50.0%) than in patients with unresectable cancer (N = 16, 66.7%), was similar in patients treated without or with CDDP (N = 14, 63.6% and N = 13, 54.2%), and was higher in patients with the intestinal histological subtype (N = 23, 62.2%) than in patients with diffuse/other histological subtypes (N = 4, 44.4%).

Treatments received after disease progression

The subsequent treatments following disease progression were irinotecan in 16 patients (continued for a median of 43 days; range 1–218 days), and radiotherapy in six patients (continued for a median of 14 days; range 1–38 days) (Table 3). Trastuzumab was continued beyond progression in the subsequent line of treatment in nine patients, and reintroduced during the subsequent lines of treatment in a further 14 patients.

Table 3.

Therapy administered to patients following the phase II study

| Treatment duration (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic regimen | N | Median | Range |

| CPT‐11 | 16 | 43 | 1–218 |

| Radiotherapy | 6 | 14 | 1–38 |

| CPT‐11 + CDDP | 4 | 113 | 57–275 |

| Docetaxel | 4 | 25 | 21–43 |

| Capecitabine + trastuzumab | 3 | 64 | 22–162 |

| Surgery | 3 | 1 | 1–1 |

| Trastuzumab | 3 | 64 | 1–189 |

| Trastuzumab + paclitaxel | 3 | 15 | 15–50 |

| CPT‐11 + trastuzumab | 2 | 155.5 | 22–289 |

| Capecitabine + CDDP + trastuzumab | 2 | 137 | 98–176 |

| CPT‐11 + MMC | 1 | 1 | n/a |

| CPT‐11 + S‐1 | 1 | 55 | n/a |

| Capecitabine | 1 | 148 | n/a |

| Capecitabine + CDDP + CPT‐11 | 1 | 163 | n/a |

| Capecitabine + CPT‐11 + trastuzumab | 1 | 55 | n/a |

| Paclitaxel | 1 | 36 | n/a |

| S‐1 | 1 | 56 | n/a |

| S‐1 + CDDP | 1 | 98 | n/a |

| S‐1 + trastuzumab | 1 | 105 | n/a |

CPT‐11: camptothecin‐11; CDDP: cisplatin; MMC: mitomycin C; n/a: not applicable.

Discussion

This is the first report of an open‐label prospective phase II study to examine the effectiveness and safety of trastuzumab in combination with paclitaxel in patients with previously treated, HER2‐positive advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. This combination therapy achieved favorable ORR, PFS and OS compared with paclitaxel alone.10, 11 The combination therapy was also tolerable, with a low rate of grade 3/4 adverse events; most adverse events were of grades 1/2. The primary endpoint was met because the ORR was 37% (95% CI 23–52%), which exceeded the hypothesized ORR of 15%.

In this study, trastuzumab and paclitaxel were administered as the second‐ or later‐line therapy in patients who had never previously received trastuzumab, because trastuzumab had only been approved in Japan just before starting this study. In addition, the standard adjuvant therapeutic regimen consists of fluorouracil alone without trastuzumab. Thus, the evidence obtained in this study cannot be applied directly to future patients with HER2‐positive cancer because these patients should have received trastuzumab as part of first‐line treatment. Further studies are still imperative in order to justify the administration of trastuzumab beyond progression in combination with paclitaxel because trastuzumab beyond progression may provide some benefits for metastatic breast cancer patients.15 Nevertheless, the current study remains clinically relevant because it provides good evidence supporting an alternative treatment regimen in patients with HER2‐positive cancer who cannot tolerate fluorouracil, and also in those who, for some reason, did not receive trastuzumab as part of first‐line treatment. The clinical effectiveness and safety data obtained will be useful for those who treat HER2‐positive gastric cancer.

Two prior reports evaluated weekly paclitaxel as second‐line chemotherapy, and reported median OS periods of 6.9 and 9.5 months.10, 11 In contrast, the OS in our study was remarkably prolonged at 17.1 months. There are two possible explanations for these differences. First, our study included several recurrent patients after adjuvant chemotherapy (16/46, 34.8%). Of these patients, 12 received the protocol treatment as the initial therapy for recurrent disease without prior use of platinum and showed favorable OS of 18.7 months. Second, the proportion of patients who received subsequent chemotherapy after disease progression (following therapy) was high (31/46 patients, 67.4%). The subsequent therapy might also contribute to the large difference between OS and PFS in this study (17.1 and 5.1 months, respectively). Of the 31 patients who received subsequent chemotherapy after disease progression, nine continued to use trastuzumab and 14 received at least one regimen that included trastuzumab. Similar to breast cancer, the use of trastuzumab beyond disease progression might also contribute to favorable survival for advanced gastric cancer patients, as has been documented for advanced breast cancer.15

Although trastuzumab was used in combination with paclitaxel in this study, the incidence of grade 3/4 adverse events was similar to that in an earlier study using paclitaxel alone.9 In that study, neutropenia (28.7%), anemia (21.3%), leukocytopenia (20.4%), anorexia (7.4%) and sensory neuropathy (7.5%) were the most common grade 3/4 adverse events in the cohort of 108 patients treated with paclitaxel. In our study of 46 patients, neutropenia (32.6%), leukopenia (17.4%), anemia (15.2%), hypoalbuminemia (8.7%) and peripheral sensory neuropathy (6.5%) were the most common grade 3/4 adverse events. These results suggest that trastuzumab may not enhance the toxicity of weekly paclitaxel.

Several studies have examined the effectiveness and safety of the monoclonal antibody ramucirumab (a vascular endothelial growth factor‐2 receptor 2 antagonist)14, 16 and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib17 in patients with gastric cancer. In REGARD,14 the median OS was 5.2 vs. 3.8 months (p = 0.047) and PFS was 2.1 vs. 1.3 months (p < 0.0001) in the ramucirumab + best supportive care vs. placebo + best supportive care groups, respectively, in patients with advanced gastric or gastro‐esophageal junction adenocarcinoma and disease progression after first‐line platinum‐containing or fluoropyrimidine‐containing chemotherapy. In RAINBOW,16 the median OS was 9.6 vs. 7.4 months (p = 0.017) and PFS was 4.4 vs. 2.9 months (p < 0.0001) in the ramucirumab + paclitaxel vs. placebo + paclitaxel groups, respectively, in patients with advanced gastric or gastro‐esophageal junction adenocarcinoma and disease progression on or within 4 months after first‐line chemotherapy (platinum plus fluoropyrimidine with or without an anthracycline). Studies to compare the effectiveness of trastuzumab versus ramucirumab are warranted. TyTAN17 compared lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in Asian patients with HER2‐positive advanced gastric cancer. The median OS was 11.0 vs. 8.9 months (p = 1.044) and PFS was 5.4 vs. 4.4 months (p = 0.244) in the lapatinib + paclitaxel vs. paclitaxel alone groups. The results of that study suggest that lapatinib is no more effective than paclitaxel alone in HER2‐postive advanced gastric cancer.

However, there are some limitations of this study. In particular, because this is not a randomized comparative study, we cannot confirm whether similar patient outcomes would have been observed using other therapies or using paclitaxel alone. In addition, the survival benefit of trastuzumab as part of later‐line chemotherapy cannot be confirmed. Accordingly, it is unclear how the survival benefit observed with this regimen compares with currently used regimens. Moreover, the long OS relative to PFS and TTF could be related to slower progression following trastuzumab therapy or could be related to subsequent therapies. These possibilities will need to be addressed in future studies in which trastuzumab are compared with other anticancer drugs. The inclusion of only Japanese patients may also limit the generalizability of this study. Finally, we used RECIST version 1.0 instead of the more recent version 1.1, and this may introduce some bias in terms of assessing tumor responses. However, the extent of this bias is likely to be low and is therefore unlikely to affect the clinical implications of our findings. We are confident that the generalizability of our results and their relevance to clinical practice are unlikely to be compromised by the use of RECIST version 1.0 instead of RECIST version 1.1.

In conclusion, trastuzumab in combination with paclitaxel was generally well tolerated in trastuzumab‐naïve patients with HER2‐positive, previously treated, advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. The ORR, OS and PFS were favorable in this cohort of patients. The present results also suggest that adding trastuzumab to weekly paclitaxel may be a treatment option for these patients. Randomized trials may be required to confirm the benefits of this combination on survival compared with other treatment regimens, such as paclitaxel alone.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nicholas D. Smith, PhD and Keyra Martinez Dunn, MD, for providing editorial support. The authors also thank the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer for their support, particularly Yukari Kawamura and Minako Nakashima for data management and analysis.

Conflict of interest: K. Nishikawa has received honoraria from Chugai. T. Yoshikawa has received honoraria from Chugai, Taiho, Yakult, Lilly, Ono, Takeda, Nihon‐Kayaku, Abbott, Johnson and Johnson, Covidien, and Olympus. T. Masuishi has received honoraria from Chugai. N. Boku has received honoraria from Chugai. Y. Yamada has received honoraria from Chugai, Taiho, Yakult Honsha. Y. Kodera has received research funding from Chugai and Bristol Myers Squibb. K. Yoshida has received honoraria from Chugai, and research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb and Chugai. S. Morita has received honoraria from Chugai. Y. Kitagawa has received research funding from Chugai, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Nippon Kayaku. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;358:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, V325 Study Group , et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first‐line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 study group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4991–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, et al. S‐1 plus cisplatin versus S‐1 alone for first‐line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, ACTS‐GC Group , et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S‐1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1810–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, et al. Five‐year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S‐1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim Do H, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thuss‐Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, et al. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second‐line chemotherapy in gastric cancer: a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, COUGAR‐02 Investigators , et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR‐02): an open‐label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H, et al. Randomized, open‐label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hironaka S, Zenda S, Boku N, et al. Weekly paclitaxel as second‐line chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2006;9:14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kodera Y, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Chubu Clinical Cancer Group , et al. A phase II study of weekly paclitaxel as second‐line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer (CCOG0302 Study). Anticancer Res 2007;27:2667–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, ToGA Trial Investigators , et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2‐positive advanced gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:687–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, REGARD Trial Investigators , et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014;383:31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Minckwitz G, du Bois A, Schmidt M, et al. Trastuzumab beyond progression in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2‐positive advanced breast cancer: a German Breast Group 26/Breast International Group 03‐05 study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1999–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, RAINBOW Study Group , et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro‐oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double‐blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1224–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, et al. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second‐line treatment of HER2‐amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN—a randomized, phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]