Abstract

Background

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an emerging coccidian parasite that causes endemic and epidemic diarrheal disease called cyclosporiasis, and this infection is associated with consumption of contaminated produce or water in developed and developing regions. Food-borne outbreaks of cyclosporiasis have occurred almost every year in the USA since the 1990s. Investigations of these outbreaks are currently hampered due to lack of molecular epidemiological tools for trace back analysis. The apicoplast of C. cayetanensis, a relict non-photosynthetic plastid with an independent genome, provides an attractive target to discover sequence polymorphisms useful as genetic markers for detection and trace back analysis of the parasite. Distinct differences in the apicoplast genomes of C. cayetanensis could be useful in designing advanced molecular methods for rapid detection and, subtyping and geographical source attribution, which would aid outbreak investigations and surveillance studies.

Methods

To obtain the genome sequence of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast, we sequenced the C. cayetanensis genomic DNA extracted from clinical stool samples, assembled and annotated a 34,146 bp-long circular sequence, and used this sequence as a reference genome in this study. We compared the genome and the predicted proteome to the data available from other apicomplexan parasites. To initialize the search for genetic markers, we mapped the raw sequence reads from an additional 11 distinct clinical stool samples originating from Nepal, New York, Texas, and Indonesia to the apicoplast reference genome.

Results

We identified several high quality single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertion/deletions spanning the apicoplast genome supported by extensive sequencing reads data, and a 30 bp sequence repeat at the terminal spacer region in a Nepalese sample. The predicted proteome consists of 29 core apicomplexan peptides found in most of the apicomplexans. Cluster analysis of these C. cayetanensis apicoplast genomes revealed a familiar pattern of tight grouping with Eimeria and Toxoplasma, separated from distant species such as Plasmodium and Babesia.

Conclusions

SNPs and sequence repeats identified in this study may be useful as genetic markers for identification and differentiation of C. cayetanensis isolates found and could facilitate outbreak investigations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1896-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cyclospora cayetanensis, Apicoplast genome, Genomics, Next generation sequencing

Background

Cyclospora cayetanensis belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa, which is a large group of protists with phylogenetic ties to dinoflagellates and ciliates [1, 2]. Most apicomplexans are obligatory parasites causing several forms of human and animal diseases such as malaria (caused by Plasmodium spp.), toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii), coccidiosis in poultry (Eimeria spp.), babesiosis (Babesia spp.), theileriosis (Theileria spp.) and cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidium spp.) [3].

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a parasite recognized as a significant cause of diarrheal illness worldwide. Sporadic cases and outbreaks have been reported from many countries. When epidemiologic data are available most of the cases have been associated with the consumption of contaminated food and/or water [4–7]. Food-borne outbreaks of cyclosporiasis have been reported in the USA since the mid 1990’s [8] (http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/index.html). Without molecular epidemiologic tools, it can be difficult to link cases to particular food vehicles and sources, thereby hampering the timely implementation of measures to control and prevent outbreaks. The development of molecular methods for the detection and characterization of C. cayetanensis isolates is therefore a priority for US public health agencies [9].

Apicomplexan parasites have an organelle called the apicoplast, a vestigial non-photosynthetic plastid originating from an ancient endosymbiotic algal ancestor [10–13]. Previous studies have shown that the apicoplast is involved in critical metabolic processes such as, heme and isoprenoid biosynthesis, fatty acid synthesis [11, 14–17], and is essential for growth in Plasmodium falciparum [18]. Because apicoplasts are vital to the survival of the parasites, they provide an attractive target for antiparasitic drugs [19, 20]. The sequence, gene content and map of various apicoplast genomes, including C. cayatenensis apicoplast genome, have been reported [21–25]. The apicoplast genomes of these parasites range 30 to 35 kb in size [3]. The structure and gene content of the apicoplast genomes are highly conserved; the genome of each apicomplexan species commonly encodes small subunit (SSU) and large subunit (LSU) rRNAs (rrs and rrl), three subunits of the bacteria-type RNA polymerase (rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2), 16 ribosomal proteins, an EF-Tu, a ClpC-like protein and 24 tRNA species [3]. Most of the apicoplast genomes contain an inverted repeat (IR) consisting of rrs, rrl, and nine tRNA genes at both ends. Due to their non-recombining and co-inherited evolutionary nature, apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes have recently been used in the development of barcoding tools for tracking Plasmodium spp. [26–28].

Here we report the end-sequence curated and annotated complete reference genome for the C. cayetanensis apicoplast and present a proof of concept for using this reference to identify genomic markers for potential molecular epidemiology applications. Comparative analysis of sequence and gene organization of 11 C. cayetanensis apicoplast genomes originating from different geographical regions and the reference genome was performed. The results showed that the apicoplast genomes from C. cayetanensis strains are highly conserved with a few distinct polymorphisms. We identified 25 SNPs spanning the apicoplast genome, and a unique 30 bp- long repeat insertion sequence in a Nepalese sample. Phylogenetic comparisons of apicoplasts from different parasitic members of the Apicomplexa confirmed the existence of a conserved genomic structure and a common evolutionary history among these organisms. We identified a set of core proteins, conserved in many apicomplexan apicoplasts which potentially could be used for molecular typing and evolutionary studies. The SNPs and sequence repeats identified in this study could be used as genomic markers for source identification of outbreak strains of C. cayetanensis enabling molecular trace back analysis of outbreaks with high resolution.

Methods

Cyclospora cayetanensis samples

Some of the stool samples included in this study were originally submitted to CDC for confirmatory diagnosis of parasitic infections. Other stool samples containing C. cayetanensis oocysts were generously supplied by Professor Jeevan Sherchand, (Microbiology and Public Health Research Laboratory at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal), Ynes Ortega (The University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, USA), Cathy Snider (Texas Department of State Health Services Laboratory), and staff at the Embassy of the United States in Jakarta, Indonesia. Cyclospora cayetanensis oocysts were purified from stool samples by a method similar to that developed for Cryptosporidium [29]. Briefly, C. cayetanensis oocysts were recovered from sieved fecal samples by differential sucrose gradient centrifugations (twice) and a cesium chloride (CsCl) gradient centrifugation. Sheather’s solution [500 g sucrose, 320 ml H20 9 ml aqueous phenol (85%)] was used in 1:2, and 1:4 dilutions for sucrose gradient centrifugations. Gradients were prepared by pipetting 20 ml 1:2 Sheather’s solution and underlying it with 20 ml 1:2 Sheather’s solution, in 50 ml conical centrifuge tubes. Sieved fecal samples (10 ml) overlaid onto the gradient slowly. After centrifugation at 1000 g for 25 min. at 4 °C, oocysts were collected from 1:2 upper layer of the tube without disturbing the gradient. For cesium chloride gradient centrifugation; oocysts purified via sucrose gradient centrifugations were re-suspended in 0.5 ml saline, and carefully overlaid on 1 ml CsCl gradient solution (21.75 g CsCl- sp. gr. 1.15- in 103.25 ml dH2O) in a 1.7 ml siliconized micro centrifuge tube. Centrifugation was done at 16.000× g for 3 min. Oocysts were carefully collected from the layer between sample and CsCl fractions. Partially purified C. cayetanensis oocysts were counted using a hemocytometer and a Zeiss Axio Imager D1 microscope with an HBO mercury short arc lamp and a UV filter (350 nm excitation and 450 nm emission).

DNA preparation and sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from C. cayetanensis oocyst preparations partially purified from clinical fecal samples, using the ZR Fecal DNA MiniPrep™ kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions with one modification. OmniLyse® cartridge (Claremont BioSolutions, Upland, CA, USA) was used to replace the bead beating step of the protocol provided by the ZR Fecal DNA MiniPrep™ kit. DNA concentration was measured with a Qubit 1.0 Fluorimeter using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of the genomic DNA was performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the Nextera XT, Nextera (Illumina), and Ovation (NuGEN, San Carlos, CA, USA) library preparation kits. Approximately 10 to 16 pmol of each library was paired-end sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina).

Bioinformatic analysis

The CLC Genomics Workbench toolkit (8.0) (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, USA) was used for trimming the adaptor sequences from the whole genome sequencing (WGS) reads and subsequent genome assembly. Manual sequence curation was carried out in building the reference genome from a partial NGS assembly from NF1 sample and two contigs of HCNY WGS assembly (GenBank accession number LIGJ00000000). Bowtie2 (when custom databases were used for mapping on to selected genomes), and Geneious 9.0.5 (for mapping and visualization of the coverage). Mapped reads on Geneious 9.0.5 were used to generate consensus apicoplast sequences for manual curation. Blast analysis (NCBI reference) and Geneious 9.0.5 were used extensively to generate the final genome assembly by multiple alignments. An outline of the workflow used in sequenced analysis is given in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

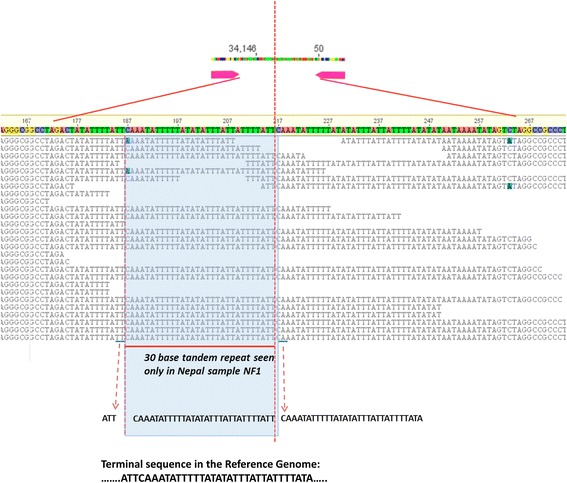

A 300 bases long stretch of sequence (Additional file 2: Figure S2a) with the 30-bp unique insert was artificially created based on the end- and start- positions of a partial NF1 assembly. Read mappings and alignments were carried out using Geneious 9.0.5 and MEGA 7 suite as necessary. Specific reads from NF1 sample targeting this repeat region were manually curated to generate Fig. 5. Reads from other samples were mapped to this fragment resulting in a misalignment at the insert sequence to generate the illustration in Additional file 2: Figure S2b.

Fig. 5.

A 30 bp tandem repeat inserted into the terminal spacer sequences of NF1, a sample from Nepal. Dashed vertical red line represents the tail to head connection in the apicolast genome sequence. Multiple alignments of raw MiSeq reads are shown in black. Inserted bases are shown in the blue box with flanking end “ATT” and start “CAAA…..ATA” sequences. Typical terminal sequence stretch seen in Reference Genome is shown at the bottom of the illustration

Initially, the reference apicoplast assembly was submitted to MAKER2 web annotation server (http://www.yandell-lab.org/software/mwas.html) for de novo annotation. RATT tool was used to transfer annotations mainly from Eimeria tenella (AY217738) [21] and also from a recently published C. cayetanensis apicoplast molecule (KP866208) [25]. Both versions of annotation of the reference genome were manually curated and corrected. An apicoplast core protein set was generated based on the presence of each of the reference genome assembly proteins available in the GenBank annotations for various species listed below. Specific alterations in the two C. cayetanensis consensus genomes were manually carried out in comparison with the reference genome using Geneious 9.0.5. Gaps (denoted by ‘N’) in the aligned genome assemblies were removed for phylogenetic analysis (resulting in Additional file 3). Neighbor Joining method was used as per the defaults on MEGA 6 and 7 [30] to build the phylogenetic tree with 12 C. cayetanensis apicoplast genomes (Additional file 4: Figure S4). CGViewer server located at http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/ was used to create visualization of in-built blast tool analysis. ProgressiveMauve [31] algorithm implemented in Geneious 9.0.5 as a plug-in was used for whole genome alignment and visualization for interspecies genome comparisons. The reference genome from this work was compared with Babesia bovis T2Bo (NC_011395), Babesia microti RI (LK028575), Babesia orientalis Wuhan (NC_028029), Leucocytozoon caulleryi (NC_022667), Plasmodium chabaudi (HF563595), P. falciparum HB3 (NC_017928), Theileria parva-Muguga (NC_007758), E. tenella (AY217738), C. cayetanensis HEN01 (KP866208), T. gondii (U87145), Sarcocystis neurona SN3 (contigs contig02351 and contig02350 from WGS assembly JAQE01002351) and Neospora caninum Liverpool (CADU01000154). To create S. neurona SN3 apicoplast, based on the description of the apicoplast in [32], the two contigs were aligned with the T. gondii genome and fused together to form a pseudomolecule for this work. GenBank annotations, wherever available, from these records were extracted and compared to generate a core apicoplast protein set.

Results

Assembly and annotation of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast reference genome

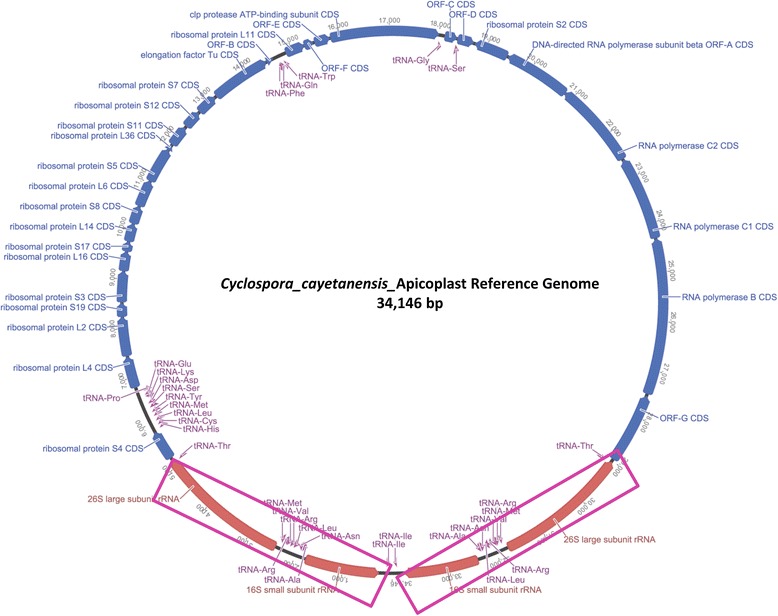

A local database of apicoplast genome sequences from Eimeria spp. and C. cayetanensis HEN01 was routinely used to collect apicoplast-specific reads from NGS datasets by Bowtie2 [33] mapping, and for identifying apicoplast contigs from genome assemblies by BLAST. An initial, gapped scaffold of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast genome was built using the NGS reads from a Nepalese sample NF1. By comparing 45 Mb HCNY C. cayetanensis draft genome assembly (LIGJ00000000) with our local database, two contigs (312 and 451) were identified. The main body of the apicoplast genome was coded by the 24 kb long contig 312 and the contig 451 constituted the approximately 5.5 kb fragment found as two inverted repeats in the apicoplast genome (Fig. 1). The NF1 scaffold was merged with the HCNY apicoplast contigs to create a consensus C. cayetanensis draft sequence assembly that was approximately 35 kb long. Approximately 25 million of WGS reads from samples NF1 and HCNY were mapped to this draft apicoplast genome using Bowtie2 and a mapping tool implemented in Geneious suite to collect reads targeting apicoplast sequences. Around one million of apicoplast-specific reads were used to refine the draft assembly of the artifacts arising from de novo assembly processes (such as insertion-deletions, extended end sequences, mis-assembly due to the ~5 kb repeats and random nucleotide polymorphisms). The E. tenella apicoplast genome (AY217738) was used to define the ends of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast assembly as it represented a typical apicoplast genome [21] from the closest species to C. cayetanensis. WGS reads from different sequencing runs using Nextera XT and Ovation libraries of NF1 and HCNY samples were used to verify the sequence at the nucleotide level. The manual curation of this draft sequence for error correction, confirmation of the end sequences, and resolution of the structure of the apicoplast genome by extensive reads-mapping, resulted in a circular, 34,146 bp long C. cayatenensis apicoplast genome (KX189066) which was used as the reference for intra-species and interspecies sequence comparisons in this paper (Fig. 1). In depth analysis with mapping of apicoplast reads from many samples confirmed the discrete difference in the length and terminal ends of this reference genome and the published genome from sample HEN01 (Additional file 5: Figure S5).

Fig. 1.

Cyclospora cayetanensis consensus apicoplast genome. The 34,146 nucleotide apicoplast genome was annotated using MAKER 2 server for de novo gene prediction; RATT tool [51] was used to transfer annotations from E. tenella. The predicted features were manually curated using comparison of the two annotation files. Sequences of the longest fragments of two terminal inverted repeat regions: 1–5147 and 28,999–34,146 bases, are shown in purple boxes

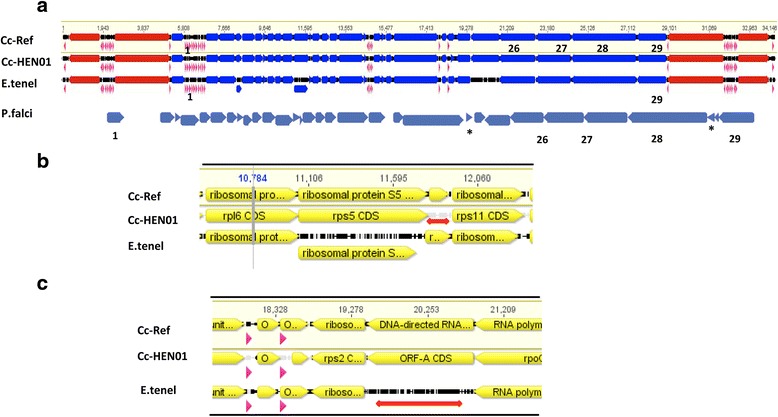

Comparison of annotations of apicoplast genomes from E. tenella (AY217738), C. cayetanensis CHN HEN01 (KP866208), and de novo gene prediction of the new reference genome confirmed the presence of 29 protein coding genes, 33 tRNA and four rRNA genes (Fig. 2a and Table 1). The overall annotation of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast reference genome with respect to E. tenella and the C. cayetanensis HEN01 strain was highly comparable as illustrated in Fig. 2a with two exceptions: (i) A partial ribosomal protein L36 was missing from the HEN01 sequence (KP866208), but was retained in our reference genome annotation (Fig. 2b); (ii) A previously unannotated ORF-A gene was identified in the E. tenella GenBank record AY217738 (Fig. 2c). Predicted apicoplast proteins from other apicomplexan parasites listed earlier were compared to evaluate the C. cayetanensis reference genome annotations. Twenty-nine proteins found in the C. cayetanensis reference genome were found in most other apicoplasts and designated as the core apicoplast proteome in Apicomplexa (Fig. 2a, Track P.falci and Table 1, column 6). Core protein analysis facilitated identification of similar peptides with different names from different organisms. For example, peptides similar to SufB- or ycf24-domain containing protein ORF470 in Plasmodium spp. (LN999985 P. falciparum 3D7) are sometimes annotated as ORF-G in C. cayetanensis HEN01 and E. tenella AY217738 (peptide 29 in Fig. 2a). Furthermore, ORF-A is often reported to be missing in some apicomplexans [Sarcocystis neurona [32]; T. gondii (U87145); E. tenella (AY217738)] but we identified the protein in E. tenella (Fig. 2c), and in T. gondii assembly U87145, and in the S. neurona SN3 apicoplast pseudomolecule generated as part of this study (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Complete apicoplast annotation and identification of core apicoplast proteins. a Draft annotations from C. cayetanensis reference genome (Cc-Ref) were aligned with KP866208 (Cc-HEN01 C. cayetanensis HEN01 strain), AY217738 (E.tenel: Eimeria tenella). The annotations were then manually curated to define gene boundaries (Table 1) and to correct any anomalies (b and c) in the assemblies. The final C. cayetanensis reference genome annotations were compared with LN999985 (P.falci: Plasmodium falciparum 3D7) and predicted proteins from other apicomplexan apicoplasts available in GenBank Twenty-nine core proteins present in most of the available apicoplast genomes were identified in the C. cayetanensis reference Table 1. Core apicoplast proteins 1–29 in C. cayetanensis (track Cc-ref) are illustrated above from left to right. In Tracks a-c, arrows in rRNA CDS are in red, tRNA in purple and proteins are in blue. In Track d, only the predicted proteome is shown in dark blue. b Cyclospora homolog of RPL36 (ribosomal protein L36) was included (track Cc-Ref) between RPS5 and RPS11 in the reference genome annotation. This partial peptide homologous to an Eimeria protein (track E.tenel) is not available (indicated by a red line) from the KP866208 genome annotation file in GenBank (track Cc-HEN01). c Based on the core apicoplast proteins identified in a wide variety of apicomplexan parasites, a homolog of ORF-A protein found in C. cayetanensis reference genome (track Cc-Ref) was predicted and confirmed to be present in Eimeria (track E.tenel). Currently this CDS is missing (indicated by a red line) from the annotations of E. tenella (AY217738) and other eimeriids. Track Cc-HEN01 represents the apicoplast coding regions of strain C. cayetanensis HEN01

Table 1.

Annotated genome of Cyclospora cayetanensis apicoplast

| Name | Strand | Start | End | Length | Core Proteins | Name | Strand | Start | End | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF-G | - | 27,539 | 28,969 | 1431 | 28 | tRNA-Ile | + | 34,061 | 34,132 | 72 |

| RPOL B | - | 24,324 | 27,488 | 3165 | 27 | tRNA-Ala | + | 32,287 | 32,359 | 73 |

| RPOL C1 | - | 22,610 | 24,312 | 1703 | 26 | tRNA-Asn | - | 32,187 | 32,259 | 73 |

| RPOL C2 | - | 20,830 | 22,590 | 1761 | 26 | tRNA-Leu | + | 32,102 | 32,181 | 80 |

| ORF-A | - | 19,469 | 20,827 | 1359 | 25 | tRNA-Arg | + | 32,025 | 32,098 | 74 |

| RiboProtein S2 | - | 18,756 | 19,445 | 690 | 24 | tRNA-Val | + | 31,945 | 32,016 | 72 |

| ORF-D | + | 18,397 | 18,732 | 336 | 23 | tRNA-Arg | - | 31,855 | 31,927 | 73 |

| ORF-C | + | 18,134 | 18,391 | 258 | 22 | tRNA-Met | - | 31,771 | 31,844 | 74 |

| clp protease | + | 15,818 | 18,010 | 2193 | 21 | tRNA-Thr | - | 29,016 | 29,087 | 72 |

| ORF-E | + | 15,482 | 15,799 | 318 | 20 | tRNA-Ser | + | 18,391 | 18,475 | 85 |

| ORF-F | + | 15,267 | 15,464 | 198 | 19 | tRNA-Gly | + | 18,027 | 18,097 | 71 |

| RiboProtein L11 | + | 14,874 | 15,263 | 390 | 18 | tRNA-Trp | + | 14,774 | 14,845 | 72 |

| ORF-B | + | 14,447 | 14,592 | 146 | 17 | tRNA-Gln | + | 14,692 | 14,763 | 72 |

| elongation factor Tu | + | 13,224 | 14,441 | 1218 | 16 | tRNA-Phe | - | 14,605 | 14,677 | 73 |

| RiboProtein S7 | + | 12,765 | 13,190 | 426 | 15 | tRNA-Pro | + | 6684 | 6757 | 74 |

| RiboProtein S12 | + | 12,369 | 12,734 | 366 | 14 | tRNA-Glu | + | 6593 | 6666 | 74 |

| RiboProtein S11 | + | 11,912 | 12,331 | 420 | 13 | tRNA-Lys | - | 6491 | 6562 | 72 |

| RiboProtein L36 | + | 11,776 | 11,892 | 117 | 12 | tRNA-Asp | + | 6404 | 6478 | 75 |

| RiboProtein S5 | + | 11,055 | 11,774 | 720 | 11 | tRNA-Ser | + | 6312 | 6396 | 85 |

| RiboProtein L6 | + | 10,503 | 11,051 | 549 | 10 | tRNA-Tyr | + | 6207 | 6291 | 85 |

| RiboProtein S8 | + | 10,136 | 10,498 | 363 | 9 | tRNA-Met | + | 6125 | 6197 | 73 |

| RiboProtein L14 | + | 9766 | 10,131 | 366 | 8 | tRNA-Leu | + | 6014 | 6100 | 87 |

| RiboProtein S17 | + | 9555 | 9761 | 207 | 7 | tRNA-Cys | + | 5930 | 6000 | 71 |

| RiboProtein L16 | + | 9165 | 9551 | 387 | 6 | tRNA-His | + | 5852 | 5925 | 74 |

| RiboProtein S3 | + | 8533 | 9159 | 627 | 5 | tRNA-Thr | + | 5093 | 5164 | 72 |

| RiboProtein S19 | + | 8246 | 8524 | 279 | 4 | tRNA-Met | + | 2336 | 2409 | 74 |

| RiboProtein L2 | + | 7444 | 8241 | 798 | 3 | tRNA-Arg | + | 2253 | 2324 | 72 |

| RiboProtein L4 | + | 6797 | 7435 | 639 | 2 | tRNA-Val | - | 2164 | 2235 | 72 |

| RiboProtein S4 | + | 5211 | 5816 | 606 | 1 | tRNA-Arg | - | 2082 | 2154 | 73 |

| 16S SSU rRNA | + | 32,403 | 33,905 | 1503 | tRNA-Leu | - | 1998 | 2078 | 81 | |

| 26S LSU rRNA | - | 29,033 | 31,746 | 2714 | tRNA-Asn | + | 1921 | 1993 | 73 | |

| 26S LSU rRNA | + | 2434 | 5147 | 2714 | tRNA-Ala | - | 1821 | 1895 | 75 | |

| 16SSSU rRNA | - | 275 | 1777 | 1503 | tRNA-Ile | - | 48 | 119 | 72 |

Cyclospora cayetanensis apicoplast genome alignment with nine other apicomplexan species

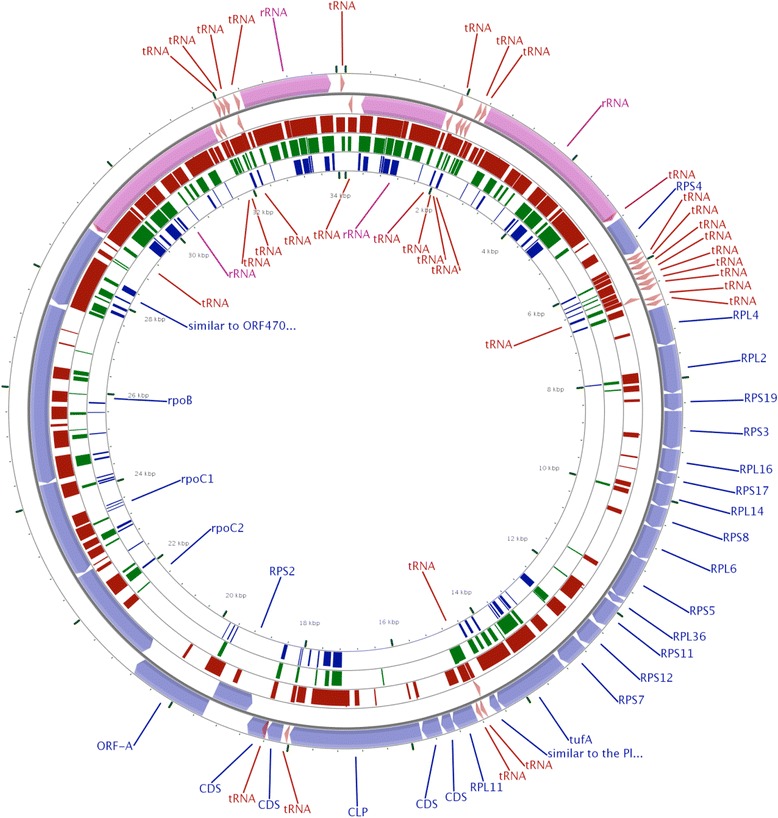

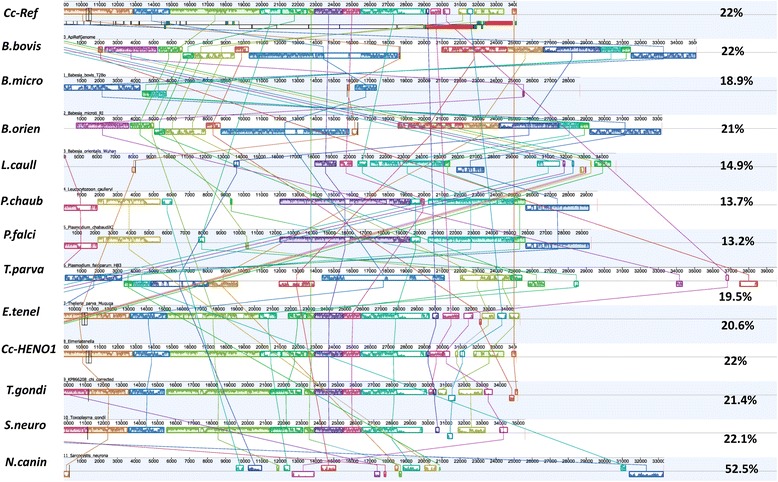

The genome structure of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast was compared with datasets from other apicomplexans in order to confirm the gene order and gene content. Whole genome comparison was carried out using NCBI Blast, Blast-feature built in CGViewer (Fig. 3) and Mauve implemented on the Geneious software suite (Fig. 4). The C. cayetanensis reference genome displayed 85% average nucleotide identity compared to E. tenella by NCBI Blast while this value decreased with T. gondii (72%) and P. falciparum 3D7 (68%). This significant local nucleotide divergence pattern from the Blast analysis was captured in the Fig. 3. When the multiple apicoplast genomes were aligned using Mauve algorithm, the varying lengths due to possible insertion and deletion of sequences are observed in Fig. 4. The GC content of the apicoplast genomes, marked on respective tracks in Fig. 4, ranged from 13.2 to 52.5% suggesting a diverse evolutionary history of these organisms. In spite of the species-level nucleotide differences, the apicoplast genomes in many parasitic apicomplexans appear to be globally comparable, as expected. For example, when the apicoplast genomes from C. cayetanensis, Eimeria and Plasmodium were compared, Eimeria showed higher sequence conservation to C. cayetanensis reference genome than to Plasmodium (Fig. 3). But the overall protein coding gene content appears not to have changed in these three species (Fig. 2a); all of the core proteins identified in C. cayetanensis were also present in Plasmodium, a relatively distant species. Similar pattern was observed when 12 apicoplast genomes from two distinct classes of Apicomplexa (Aconoidasida and Conoidasida) were compared in Mauve. Mauve analysis identified a varied number of blocks of sequence similarity which followed the line of evolutionary distance among distant genera like Babesia, Plasmodium and Cyclospora. In general, aconoidasidans like Babesia and Theileria had more in common with Plasmodium than with Cyclospora and other conoidasidans, and vice versa (Fig. 4) in terms of conserved sequence and structure. But the predicted apicoplast proteome of this diverse set of apicomplexans analyzed showed fewer deletions and protein coding gene acquisitions (data not shown; all comparisons based on GenBank annotations of the sequence files listed in the Methods). The determination of core apicoplast protein and comparison with other apicomplexans confirmed that the C. cayetanensis reference genome reported in this work is complete, and can be used for finding sequence variations.

Fig. 3.

BLAST analysis of the Cyclospora apicoplast reference genome with other apicomplexans. Apicoplast genomes from an eimeriid, E. tenella and a sarcocystid, T. gondii (brown and green bars, respectively) and a plasmodiid, P. falciparum 3D7 (violet) are compared with the C. cayetanensis apicoplast (outer circles with purple, blue and maroon bands) using CGview software with its built-in Blast tool with the default e-value cutoff of 0.1. The thickness of the bands indicates sequence similarity. The eimeriid and sarcocystid apicoplasts have higher nucleotide similarity while the Plasmodium apicoplast is least similar of the three recapitulating evolutionary distance between these species. The predicted proteomes of these divergent apicomplexans contain mostly conserved core gene content (Fig. 2a)

Fig. 4.

Whole genome alignment of C. cayetanensis apicoplast with 12 genomes from apicomplexan genera: Babesia, Eimeria, Leucocytozoon, Neospora, Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, Theileria and Sarcocystis. Whole genome alignment of (Track Cc-Ref) C. cayetanensis apicoplast reference genome with 12 assemblies from apicomplexans of the order Aconoidasida: (B.bovis) Babesia bovis; (B.micro) B.microti; (B.orien) B. orientalis Wuhan; (L. caull) Leucocytozoon caulleyi; (P.chaub) Plasmodium chaubaudi chaubaudi; (P.falci) P. falciparum HB3; (T.parva) Theileria parva and the order Conoidasida: (E.tenel) E. tenella; (Cc-HEN01) C. cayatenensis HEN01; (T.gondi) T.gondii; (S.neuro) S. neurona; and (N.canin) N. caninum. The GC content of the apicoplast genome from each species is displayed at the end of respective track. In addition, the apicoplast assemblies revealed re-arrangements in some species. Nucleotide divergence between members of Aconoidasida and Conoidasida is illustrated here

De novo assembly and genomic diversity of C. cayetanensis apicoplast genomes from geographically distinct samples

Metadata details of the C. cayetanensis strains used for this work and the apicoplast genomes (annotated reference KX189066 and consensus assemblies) have been submitted to NCBI for immediate release under the community Bioproject ID: PRJNA316938. WGS datasets from C. cayetanensis samples from different geographical regions (Indonesia, Nepal, New York, Texas, Rhode Island, Virginia and Guatemala) and sequence from C. cayetanensis strain HENO1 (KP866208) were mapped to the reference genome as outlined in Additional file 1: Figure S1 and the resulting consensus assemblies (Additional file 3) were analyzed for structural genomic differences. A 60 bp long intergenic terminal region separating the two tRNA-Ile genes was found to be conserved in all but one of the samples. This consisted of a 14 bp repeat (34,133–34,146 and 33–46 base positions) adjacent to the terminal tRNA-Ile gene on each end (28 bp total). A 32 bp long terminal spacer region (1–32 base positions) flanks the repeat region near the start. However, the NGS reads from the FDA NF1 sample generated from 5 different libraries consistently failed to map to these terminal regions. Further analysis revealed an additional 30-base tandem duplicate of the terminal spacer inserted with a T/A base change at the end (Fig. 5). This terminal insertion was not identified in any other samples even after deep read-mapping analysis and was thus not included in the reference genome. When the reads were targeted to a 300 bp end to start sequence that included the unique insert from NF1 sample (Additional file 2: Figure S2a), rest of the geographical samples resulted in misalignment with ambiguous or missing base positions (Additional file 2: Figure 24b). Eleven complete apicoplast genomes from seven geographical regions validated by the depth of coverage and stringent quality assurance parameters were chosen for further analysis. When the apicoplast reference genome (KX189066) was compared with the published [25] C. cayetanensis HEN01 apicoplast genome (KP866208), we found more than two dozen positions with ambiguous bases, insertions and deletions, in the latter (Additional file 5: Figure S5). None of the anomalies in the original sequence of the KP866208 assembly were observed in any of the 11 WGS datasets analyzed in this work. It was necessary to re-order the start of the KP866208 to reflect the validated end-start junction site of the newly derived reference genome. Thirty three bases from the tail end of KP866208 GenBank sequence was moved to the beginning. In addition, 19 deletions and 10 replacements resulting in a net decrease of 9 bases were carried out to reconcile the KP866208 with our reference genome. The ambiguous bases in the corrected KP866208 were replaced with ‘N’ (Additional file 3).

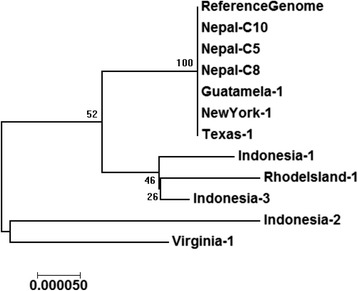

Eleven apicoplast consensus genomes derived from WGS reads (Additional file 3) were aligned against the 34,146 bp long reference genome to determine the presence of SNPs and other genomic variations or differences. Single samples each from Rhode Island, Texas, and Virginia and three samples from Indonesia showed distinct polymorphisms and indels spanning their whole genomes. Indonesia-2 and Virginia-1 samples exhibit tetrameric polymorphic repeats of A and T (Table 2). Various combinations of SNPs located in 21 positions spanning these apicoplast genomes could distinguish samples from Virginia, Indonesia and Rhode Island from those which originated from Texas, Nepal, Guatemala and New York (Table 2). Based on this ungapped alignment (Additional file 3 with 12 genomes without any gaps), a phylogenetic tree was built (Fig. 6). As expected from their alignments with the reference genome, the identical genomes of samples from Texas, New York, Nepal and Guatemala clustered together. Interestingly the three Indonesian samples appeared in separate clades indicating more extensive diversity underlying these samples from the same geographical location.

Table 2.

Nucleotide variations in the apicoplasts from geographical samples compared to the C. cayetanensis apicoplast reference genome

| Base position | Ref Genome | Rhodeisland-1 | Indonesia-1 | Indonesia-2 | Indonesia-3 | Virginia-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C | T | T | T | T | C |

| 533 | T | T | T | C | T | T |

| 557 | TTTT | AAAA | TTTT | TTTT | TTTT | AAAA |

| 1898 | A | T | T | T | T | A |

| 2242 | T | T | A | A | T | T |

| 6002 | C | C | C | C | A | C |

| 6110 | T | A | A | A | A | T |

| 7047 | C | C | C | C | C | T |

| 7373 | G | T | G | T | G | G |

| 7374 | A | C | A | C | A | A |

| 7780 | T | T | GGAT | T | T | T |

| 10,623 | C | A | C | C | C | C |

| 12,759 | T | DEL | T | T | T | T |

| 12,760 | A | DEL | A | A | A | A |

| 14,600 | A | A | DEL | A | A | A |

| 15,493 | A | T | T | T | T | A |

| 18,625 | T | A | A | A | A | T |

| 18,629 | T | C | T | T | T | T |

| 20,515 | G | G | G | G | G | A |

| 20,555 | T | T | T | T | T | G |

| 26,122 | T | T | G | T | T | G |

| 31,938 | A | A | T | T | T | A |

| 32,282 | T | A | A | A | A | T |

| 33,620 | AAAA | AAAA | AAAA | TTTT | AAAA | TTTT |

| 33,647 | A | A | A | G | A | A |

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of 11 C. cayetanensis apicoplast genomes from seven geographical regions compared with the reference genome. The percentage of replicate trees generated using Neighbor-Joining method in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) is shown next to the branches. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 suite [30]

Discussion

We found distinct differences between the C. cayetanensis apicoplast reference genome (KX189066) reported in this work and the previously reported C. cayetanensis genome assembly KP8666208 [25]. Although the annotation of both assemblies was highly similar (Figs.1 and 2a, Table 1), we found more than two dozen positions with ambiguous bases, insertions and deletions (Additional file 5: Figure S5). Interestingly none of these sequence variations were shared with any of the other 11 genomes we assembled in this study and so we removed the KP8666208 genome assembly from our clustering analysis but included it for other comparisons. The 30-bp tandem duplicated insertion in the spacer region of FDA-NF1 sample (Fig. 5) was unique to this particular sample (comparative genomic analysis details provided in Additional file 2: Figure S2). Tandem repeat structures are common in chloroplast sequences in both coding and non-coding regions and it would be interesting to capture multimeric nucleotide variations if any are found in C. cayetanensis apicoplasts. Due to its polymorphic nature and co-dominant mode of inheritance, these repeat stretches have been used as DNA markers for population genetics studies [34–37]. The biological significance of this finding in C. cayetanensis remains unknown.

Genetic variation in apicomplexans such as P. falciparum has been shown to reflect geographic distance, and population dynamics [26]. Organelle genomes are particularly informative in tracing patterns of population dynamics due to their non-recombining nature. Mitochondrial and plastid sequences have been used to search for the origins of humans [38], grapevines [39], and have also served as DNA barcodes for plants and animals [40]. We sequenced and analyzed 11 complete C. cayetanensis apicoplast genomes from seven geographical locations of sample collection to determine whether SNPs and other sequence signatures may be geographically informative. SNPs and indels identified in this study span all of the C. cayetanensis apicoplast genome and provide a higher resolution with distinct distinguishing power when compared to single gene or repeat sequence based efforts reported in the past [7, 41, 42]. The comparative genomic analyses have demonstrated the genomic diversity of C. cayetanensis apicoplasts among the sub-groups of samples used. The approach used in this study resulting in observations of inherent genomic variations in the geographical isolates may be used to develop a strategy to discern a more comprehensive survey of genetic variations from worldwide samples in the future. Apicomplexans like Plasmodium have been reported to contain a few hundred SNPs in their apicoplast genomes when larger populations of samples from many geographical areas were analyzed [26]. It is evident from Fig. 6 that the 34 kb long C.cayetanensis apicoplast genome may harbor more variations than observed in this analysis with a limited number of samples (n = 11) from 7 geographical locations. Moreover, Cyclospora is found to be common in tropical and subtropical regions but spread to countries importing the foods contaminated by the parasites [https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/epi.html]. Although the 11 samples clustered into 5 distinct groups based on approximately 25 SNP positions, the travel history of the patients and sources of contamination leading to the illness from each of the US sample collection locations could not be easily verified. Thus, we cannot determine with certainty that the sequence variations are geographically specific in those US patient samples that clustered together (Fig. 6). This highlights the necessity of collecting critical metadata of the source of sample collection to capture important information on the occurrence of the parasites in different regions. Increased number of samples from various geographical regions where C. cayetanensis is detected in foods, water or in patients coupled with clear epidemiological data would provide a better perspective of the genomic diversity. In order to encourage the Cyclospora research community to build a resource of apicoplast genomes for identifying strain-level variations from different parts of the world, we have created a “Bioproject” in NCBI titled “Cyclospora cayetanensis Geo-Genomic Profiling using Apicoplast Genomes from different Geographic Areas” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA316938) for submission of sequence data, both raw (“SRA”) and assembled (“Assembly”), and sample metadata (“BioSample”). Global researchers of Cyclospora spp. can submit their datasets to this open BioProject with assistance from the authors (GG and AD) of this work.

Whole genome assemblies from WGS reads are prone to sequence errors due to read quality and assembly processes. The apicoplast genomes are marked by a pair of 5 kb low GC content terminal repeats constituting almost 30% of the total length. The problem of missed, wrongly annotated or fragmented assemblies (present in different contigs of a WGS assembly) is characteristic of genome assemblies from NGS reads [43]. For these reasons, we evaluated the quality of our reference assembly, by comparing the predicted proteome of related parasites including Cyclospora, and Babesia among other apicomplexans, and defined a set of core apicoplast proteins found in most of the apicomplexans. Across the apicomplexan species we tested, the gene content seemed to be mostly preserved with only minor changes. In addition, the annotated core apicoplast proteins (Table 1; column 6) identified based on many apicomplexan parasites allowed a comparative genomics approach to correct a few nomenclature or mis-identification issues in published apicoplast genomes. Apicoplasts from different apicomplexans have been previously noted to contain a set of proteins with similar essential biochemical functions [44]. The analytical approaches to study the phylogenetics of apicomplexan parasites have been expanding to include more loci from mitochondria, apicoplasts and chromosomal genomes. Recently, a combination of mitochondrial, apicoplastic and chromosomal genes were found [45] to be sufficient to infer the evolutionary relationships among Eimeriid coccidians. Current work on the C. cayetanensis reference genome expands the repertoire of target sequences for extended phylogenetic analysis of apicomplexans. The genome alignment in Fig. 4 includes Aconoidasidans, (like Plasmodium and Babesia) and Conoidasidans (like Eimeria, Toxoplasma and Cyclospora) which represent differences in life cycle, host, genome size, GC content of apicoplast genomes and taxonomic positions. The range of GC content among apicomplexans from 13% (in Plasmodium), 26% (in C. cayetanensis) to 52.5% (in Neospora) is reflected in the gaps in the Mauve multiple alignment (Fig. 4). The uniformity seen in the genomes across multiple species based on available sequences confirms a suggested stable evolutionary state of plastid evolution from a common ancestor prior to species diversification [46]. It supports for the functional importance of apicoplasts as noted in other earlier reports [11, 47].

Cyclospora cayetanensis has emerged as a cause of diarrheal illness in different countries where cases of infections were not known. A large number of cases have been reported from developed and developing countries in the form of seemingly sporadic cases or outbreaks associated with food- or waterborne transmission. Consumption of imported produce has been associated with U.S. outbreaks of cyclosporiasis. Thus, it is reasonable to believe that the globalization of the food supply has been a key element for the spread of C. cayetanensis infections. There have been relatively few U.S. outbreaks of cyclosporiasis for which a food vehicle was definitively identified [48]. It is not yet clear about the potential food vehicles that can be associated with reported outbreaks during any given year. During the 2013 Texas cyclosporiasis outbreak investigation it was clear that some outbreak cases were associated with consumption of cilantro imported from the state of Puebla in Mexico. However, no definitive food vehicle was implicated for the majority of the cases reported during the outbreaks [9]. The investigations that took place in 2013 illustrated essential scientific gaps that needed be closed in order to streamline outbreak investigations; i.e. (i) absence of more sensitive and specific diagnostic methods that can improve case detection; (ii) lack of molecular epidemiology methods to link cases to each other or to particular food items; and (iii) the absence of practical tools to detect the organism in food and potential sources of contamination in the environment.

Conclusions

This study focused on closing the molecular epidemiology gap to help link clinical cases to each other, and to particular food items. The availability of genomic data and associated sample metadata from across the world should accelerate the profiling of C. cayetanensis isolates or even species of Cyclospora from diverse sources samples, e.g. zoonotic samples [49, 50] possibly leading to development of molecular tools for identification and source-tracking. The WGS-based reference genome reported in this work was completed by high quality, in depth read-mapping and comparative genomics. In the process, we have developed a framework to perform in-depth intra- and inter-species comparisons of apicoplast genomes to study the evolutionary relationship of apicomplexan parasites, and to identify specific variations in C. cayetanensis strains.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Jeevan Sherchand and Ynes Ortega for providing clinical stool samples containing C. cayetanensis oocysts. We also would like to thank Dr. Ben Tall, Dr. Chris Elkins and Dr. Hulusi Cinar for critical review of the manuscript. This study was supported by the CDC’s Advanced Molecular Detection and Response to Infectious Disease Outbreaks Initiative. Fernanda S. Nascimento was supported by the Brazilian National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) fellowship (236608/2013-4).

Funding

This study was supported by the CDC’s Advanced Molecular Detection and Response to Infectious Disease Outbreaks Initiative. Fernanda S. Nascimento was supported by the Brazilian National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) fellowship (236608/2013-4).

Availability of data and material

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. All the sample and assembly data can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA316938. C. cayatenensis apicoplast genome (KX189066).

Authors’ contributions

HNC and GG worked on the whole genome sequencing (WGS) of FDA samples, and designing the study, writing and compiling the manuscript; HNC, YQ, YW-P, WL, FN, MA, ADS, HRM, AYJ, EK, RYK purified oocysts from fecal samples from different sources, prepared DNA, participated in WGS at FDA and CDC and commented on the paper; YQ, ADS and MA helped in the use of CDC samples and data; YQ and MA led the work at CDC and provided datasets from CDC to GG for analysis; ADS and HRM participated in the study design and critically edited the manuscript; HNC was the IRB contact at FDA; GG carried out the bioinformatics analysis of genomic data from FDA and CDC and wrote the Results section. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of FDA, and identified with the file name, RIHSC- ID#10-095F and followed the CDC Human Subjects Research Protocol # 6756, titled “Use of residual diagnostic specimens from humans for laboratory methods research”.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- CsCl

Cesium chloride

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- indel

Insertion/deletion

- IR

Inverted repeat

- kb

Kilobase

- LSU

Large subunit

- Mb

Megabase

- rrl

Large subunit ribosomal RNA

- rRNA

Ribosomal RNA

- rrs

Small subunit ribosomal RNA

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SSU

Small subunit

- tRNA

Transfer RNA

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

Additional files

Workflow used in this study for variant detection in apicoplast sequences. (TIF 172 kb)

300 bp end to start sequence analysis. A) 300 bp end to start sequence with a unique insert. B) Alignment of corrected and assembled reads from NF1 samples and 10 geographical samples with the 300 bp end sequence from NF1 assembly (sample #1). Except for the reads from NFI (sample #2), rest of the samples (samples #3-#12) do not map to this fragment containing the unique insert sequence. (TIF 8706 kb)

33,598 bases long ungapped apicoplast genome sequences for building the tree in Fig. 5. KP866208_corrected was not included in this analysis. The sequences were first aligned on MEGA7 and bases positions with ‘N’ were removed from all strains to create an ungapped sequence file. MEGA 7 suite was used for this analysis as described. (FASTA 409 kb)

34,146 bp apicoplast reference genome and consensus sequences from 11 geographical strains used in the multiple alignment to identify genomic changes and clustering analysis. KP866208 was not used in the clustering analysis. Indonesia-1 apicoplast is 34,148 long with a missing base (filled in as N) in 14,602 and a ‘GGA’ insertion in 7780 base positions. Virginia-1 consensus sequence is 33,625 bases long reflecting coverage gaps. Rhodeisland-1 sequence is 34,132 bases long with gaps at 12,579-80 and 15,372-383. All gaps were filled with N for multiple-alignment and clustering analysis. The base positions are for the Reference Genome. (TIF 105 kb)

KP866208 sequence from GenBank was aligned to the reference genome KX189066 and reconciled by making the following corrections. Deletions and ambiguous (“AMBI”) bases were replaced with N. N/A indicates ‘relevant information not available’. The corrected sequence is 34,146 bp long, similar to the reference sequence. Bars in the KP866208 genome represent SNPs or indels in comparison to the reference genome. Starting length: 34,155 bases. There were 10 insertions and 19 deletions [34,155 + 10 − 19 = 34,146 bp (the length of the reference genome)]. (TIF 3729 kb)

Contributor Information

Hediye Nese Cinar, Email: hediye.cinar@fda.hhs.gov.

Yvonne Qvarnstrom, Email: bvp2@cdc.gov.

Yuping Wei-Pridgeon, Email: saaspservices@gmail.com.

Wen Li, Email: wen.li@emory.edu.

Fernanda S. Nascimento, Email: yeb7@cdc.gov

Michael J. Arrowood, Email: mja0@cdc.gov

Helen R. Murphy, Email: Helen.Murphy@fda.hhs.gov

AhYoung Jang, Email: ahyoung.jang@fda.hhs.gov.

Eunje Kim, Email: eunje.kim@fda.hhs.gov.

RaeYoung Kim, Email: raeyoung.kim@fda.hhs.gov.

References

- 1.Fast NM, Xue L, Bingham S, Keeling PJ. Re-examining alveolate evolution using multiple protein molecular phylogenies. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2002;49:30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2002.tb00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adl SM, Leander BS, Simpson AG, Archibald JM, Anderson OR, Bass D, et al. Diversity, nomenclature, and taxonomy of protists. Syst Biol. 2007;56:684–689. doi: 10.1080/10635150701494127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato S. The apicomplexan plastid and its evolution. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1285–1296. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0646-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortega YR, Sterling CR, Gilman RH, Cama VA, Diaz F. Cyclospora species - a new protozoan pathogen of humans. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1308–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortega YR, Gilman RH, Sterling CR. A new coccidian parasite (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from humans. J Parasitol. 1994;80:625–629. doi: 10.2307/3283201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterling CR, Ortega YR. Cyclospora: an enigma worth unraveling. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:48–53. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortega YR, Sanchez R. Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food-borne and waterborne parasite. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:218–234. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00026-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herwaldt BL. Cyclospora cayetanensis: a review, focusing on the outbreaks of cyclosporiasis in the 1990s. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1040–1057. doi: 10.1086/314051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abanyie F, Harvey RR, Harris JR, Wiegand RE, Gaul L, Desvignes-Kendrick M, et al. 2013 multistate outbreaks of Cyclospora cayetanensis infections associated with fresh produce: focus on the Texas investigations. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:3451–3458. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foth BJ, McFadden GI. The apicoplast: a plastid in Plasmodium falciparum and other apicomplexan parasites. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;224:57–110. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)24003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McFadden GI. The apicoplast. Protoplasma. 2011;248:641–650. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohler S. Multi-membrane-bound structures of Apicomplexa: I. The architecture of the Toxoplasma gondii apicoplast. Parasitol Res. 2005;96:258–272. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janouskovec J, Horak A, Obornik M, Lukes J, Keeling PJ. A common red algal origin of the apicomplexan, dinoflagellate, and heterokont plastids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10949–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003335107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419:498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato S, Clough B, Coates L, Wilson RJ. Enzymes for heme biosynthesis are found in both the mitochondrion and plastid of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Protist. 2002;155:117–125. doi: 10.1078/1434461000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roos DS, Crawford MJ, Donald RG, Fraunholz M, Harb OS, He CY, et al. Mining the Plasmodium genome database to define organellar function: what does the apicoplast do? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:35–46. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralph SA. Strange organelles - Plasmodium mitochondria lack a pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh E, DeRisi JL. Chemical rescue of malaria parasites lacking an apicoplast defines organelle function in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bispo NA, Culleton R, Silva LA, Cravo P. A systematic in silico search for target similarity identifies several approved drugs with potential activity against the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shears MJ, Botte CY, McFadden GI. Fatty acid metabolism in the Plasmodium apicoplast: drugs, doubts and knockouts. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2015;199:34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai X, Fuller AL, McDougald LR, Zhu G. Apicoplast genome of the coccidian Eimeria tenella. Gene. 2003;321:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imura T, Sato S, Sato Y, Sakamoto D, Isobe T, et al. The apicoplast genome of Leucocytozoon caulleryi, a pathogenic apicomplexan parasite of the chicken. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:823–828. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3712-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg A, Stein A, Zhao W, Dwivedi A, Frutos R, et al. Sequence and annotation of the apicoplast genome of the human pathogen Babesia microti. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, He L, Hu J, He P, He J, et al. Characterization and annotation of Babesia orientalis apicoplast genome. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:543. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1158-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang K, Guo Y, Zhang L, Rowe LA, Roellig DM, et al. Genetic similarities between Cyclospora cayetanensis and cecum-infecting avian Eimeria spp. in apicoplast and mitochondrial genomes. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:358. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0966-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preston MD, Campino S, Assefa SA, Echeverry DF, Ocholla H, et al. A barcode of organellar genome polymorphisms identifies the geographic origin of Plasmodium falciparum strains. Nat Commun. 2015;5:4052. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodrigues PT, Alves JM, Santamaria AM, Calzada JE, Xayavong M, et al. Using mitochondrial genome sequences to track the origin of imported Plasmodium vivax infections diagnosed in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:1102–1108. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyagi S, Pande V, Das A. Mitochondrial genome sequence diversity of Indian Plasmodium falciparum isolates. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:494–498. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276130531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arrowood MJ, Donaldson K. Improved purification methods for calf-derived Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using discontinuous sucrose and cesium chloride gradients. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:89S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb05015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blazejewski T, Nursimulu N, Pszenny V, Dangoudoubiyam S, Namasivayam S, Chiasson MA, et al. Systems-based analysis of the Sarcocystis neurona genome identifies pathways that contribute to a heteroxenous life cycle. MBio. 2015;6(1):e02445–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02445-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;94:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redwan RM, Saidin A, Kumar SV. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of MD-2 pineapple and its comparative analysis among nine other plants from the subclass Commelinidae. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:196. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0587-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deguilloux MF, Pemonge MH, Petit RJ. Novel perspectives in wood certification and forensics: dry wood as a source of DNA. Proc Biol Sci. 2002;269:1039–1046. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vendramin GG, Lelli L, Rossi P, Morgante M. A set of primers for the amplification of 20 chloroplast microsatellites in Pinaceae. Mol Ecol. 1996;5:595–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1996.tb00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaudeul M, Giraud T, Kiss L, Shykoff JA. Nuclear and chloroplast microsatellites show multiple introductions in the worldwide invasion history of common ragweed, Ambrosia artemisiifolia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cann RL, Stoneking M, Wilson AC. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature. 1987;325:31–36. doi: 10.1038/325031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De LG, Imazio S, Biagini B, Failla O, Scienza A. Pedigree reconstruction of the Italian grapevine Aglianico (Vitis vinifera L.) from Campania. Mol Biotechnol. 2013;54:634–642. doi: 10.1007/s12033-012-9605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiser PZ, Buzan EV. 20 years since the introduction of DNA barcoding: from theory to application. J Appl Genet. 2014;55:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s13353-013-0180-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Relman DA, Schmidt TM, Gajadhar A, Sogin M, Cross J, Yoder K, et al. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Cyclospora, the human intestinal pathogen, suggests that it is closely related to Eimeria species. J Infect Dis. 1996;2:440–445. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olivier C, van de Pas S, Lepp PW, Yoder K, Relman DA. Sequence variability in the first internal transcribed spacer region within and among Cyclospora species is consistent with polyparasitism. Int J Parasitol. 2001;13:1475–1487. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alkan C, Sajjadian S, Eichler EE. Limitations of next-generation genome sequence assembly. Nat Methods. 2011;8:61–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim L, McFadden GI. The evolution, metabolism and functions of the apicoplast. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:749–763. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogedengbe JD, Ogedengbe ME, Hafeez MA, Barta JR. Molecular phylogenetics of eimeriid coccidia (Eimeriidae, Eimeriorina, Apicomplexa, Alveolata): a preliminary multi-gene and multi-genome approach. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:4149–4160. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waller RF, Keeling PJ, van Dooren GG, McFadden GI. Comment on “A green algal apicoplast ancestor”. Science. 2003;301:49. doi: 10.1126/science.1083647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denny P, Preiser P, Williamson D, Wilson I. Evidence for a single origin of the 35 kb plastid DNA in apicomplexans. Protist. 1998;149:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S1434-4610(98)70009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho AY, Lopez AS, Eberhart MG, Levenson R, Finkel BS, da Silva AJ, et al. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:783–788. doi: 10.3201/eid0808.020012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eberhard ML, da Silva AJ, Lilley BG, Pieniazek NJ. Morphologic and molecular characterization of new Cyclospora species from Ethiopian monkeys: Cyclospora cercopitheci sp. n., Cyclospora colobi sp. n., and Cyclospora papionis sp. n. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:651–658. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eberhard ML, Owens JR, Bishop HS, de Almeida ME, da Silva AJ. Cyclospora spp. in Drills, Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(3):510–511. doi: 10.3201/eid2003.131368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otto TD, Dillon GP, Degrave WS, Berriman M. RATT: Rapid Annotation Transfer Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;9:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]