Abstract

The HUPO Human Proteome Project (HPP) has two overall goals: (1) stepwise completion of the protein parts list—the draft human proteome including confidently identifying and characterizing at least one protein product from each protein-coding gene, with increasing emphasis on sequence variants, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and splice isoforms of those proteins; and (2) making proteomics an integrated counterpart to genomics throughout the biomedical and life sciences community. PeptideAtlas and GPMDB reanalyze all major human mass spectrometry data sets available through ProteomeXchange with standardized protocols and stringent quality filters; neXtProt curates and integrates mass spectrometry and other findings to present the most up to date authorative compendium of the human proteome. The HPP Guidelines for Mass Spectrometry Data Interpretation version 2.1 were applied to manuscripts submitted for this 2016 C-HPP-led special issue [www.thehpp.org/guidelines]. The Human Proteome presented as neXtProt version 2016-02 has 16,518 confident protein identifications (Protein Existence [PE] Level 1), up from 13,664 at 2012-12, 15,646 at 2013-09, and 16,491 at 2014-10. There are 485 proteins that would have been PE1 under the Guidelines v1.0 from 2012 but now have insufficient evidence due to the agreed-upon more stringent Guidelines v2.0 to reduce false positives. neXtProt and PeptideAtlas now both require two non-nested, uniquely mapping (proteotypic) peptides of at least 9 aa in length. There are 2,949 missing proteins (PE2+3+4) as the baseline for submissions for this fourth annual C-HPP special issue of Journal of Proteome Research. PeptideAtlas has 14,629 canonical (plus 1187 uncertain and 1755 redundant) entries. GPMDB has 16,190 EC4 entries, and the Human Protein Atlas has 10,475 entries with supportive evidence. neXtProt, PeptideAtlas, and GPMDB are rich resources of information about post-translational modifications (PTMs), single amino acid variants (SAAVSs), and splice isoforms. Meanwhile, the Biology- and Disease-driven (B/D)-HPP has created comprehensive SRM resources, generated popular protein lists to guide targeted proteomics assays for specific diseases, and launched an Early Career Researchers initiative.

Keywords: metrics, guidelines, neXtProt, PeptideAtlas, GPMDB, Human Protein Atlas, PTMs (post-translational modifications), N-termini, SAAV (single amino acid variants), splice isoforms

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The HUPO (www.hupo.org) Human Proteome Project (HPP) (www.thehpp.org) is pursuing two overall goals:1 (1) stepwise completion of the protein parts —the draft human proteome, including confidently identifying and characterizing at least one protein product from each protein-coding gene with increasing emphasis on sequence variants, post-translational modifications (PTMs), single amino acid variants (SAAVSs), and splice isoforms of those proteins; and (2) making proteomics an increasingly integrated component of multiomics analyses throughout the biomedical and life sciences community through advances in assays, instruments, and knowledge bases for identification, quantitation, and functional assessment of proteins and proteoforms in diverse biological systems. There are 50 HPP research teams worldwide organized as the Chromosome-centric C-HPP, the Biology- and Disease-driven (B/D)-HPP, and the Affinity-Based Protein Capture, Mass Spectrometry, and Knowledgebase (Bioinformatics) Resource Pillars. This article is part of the fourth annual C-HPP-led special issue of the Journal of Proteome Research.2–4

Periodic updates of PeptideAtlas (www.peptideatlas.org) and neXtProt (www.neXtProt.org) are organized in an approximately annual cycle tied to the pipeline for submission, review, and publication of the C-HPP-led special issue of JPR in time for the HUPO World Congress in September. This year the reference versions of these databases are PeptideAtlas 2016-01 and neXtProt 2016-02 (released Jan 11, 2016). Specific Guidelines v2.0 were generated, discussed, and approved at the HUPO2015 World Congress in Vancouver and released together with the Call for Papers for this C-HPP special issue in November 2015. Authors and reviewers have been provided a checklist to facilitate compliance with the Guidelines and enhance the quality of the submissions [www.thehpp.org/guidelines]. The strategy, specifics, and significance of each of the 15 guidelines are discussed in a companion paper,5 including an update of guideline 2 version 2.0 to version 2.1.

We report here major progress on the integration of criteria for quality control of protein identification between PeptideAtlas and neXtProt as well as recent developments of the GPMDB mass spectrometry resource and the Human Protein Atlas antibody profiling resource for tissue, cellular, and subcellular protein expression. We have put special emphasis on the expansion of knowledge about post-translational modifications.

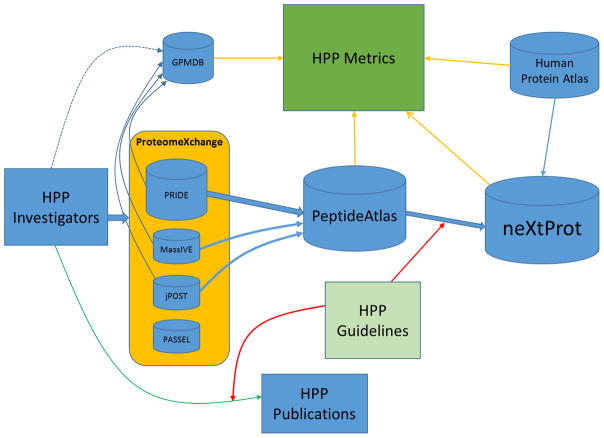

THE HUMAN PROTEOME PROJECT WORKFLOW

The overall flow of data for the HPP is depicted in Figure 1. Primary data are generated by HPP investigators in laboratories around the world. Data published in journal articles, including those in this C-HPP special issue, are subject to the ProteomeXchange requirements6 and the HPP Mass Spectrometry Data Interpretation Guidelines 2.0.5 Many other authors also submit via ProteomeXchange, which now has over 2000 released data sets, of which 900 are from human samples. All data sets (with the raw data) must be submitted to one of the ProteomeXchange proteomics data repositories, predominantly to PRIDE,7 and to a smaller extent to MassIVE for MS/MS workflows and to PASSEL8 for SRM data sets. jPOST has been added as of 2016-07. After becoming publicly available, the data sets are downloaded from these ProteomeXchange repositories to PeptideAtlas, where they are scheduled for standardized reanalysis through the PeptideAtlas processing pipeline,9 which is based on the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline.10,11 All data sets that could be processed by Oct. 1, 2015 were incorporated into the Human PeptideAtlas 2016-01 build. A final list of peptides that have met PeptideAtlas quality filtering criteria is sent to neXtProt, where they are included in the updates of the protein existence (PE) level scheme.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Human Proteome Project Workflow. The primary flow of data from investigators through ProteomeXchange to PeptideAtlas leads to protein existence (PE) classification of sequence entries in neXtProt, denoted by the thick blue arrows. Direct data transfers are denoted by thin blue arrows; the dotted blue line indicates occasional direct submission. Transfers from databases to the HPP metrics are denoted by the thin orange arrows. The larger features represent the main stream of the workflow. The 2015–2016 HPP Mass Spectrometry Data Interpretation Guidelines v2.0 are applied to primary HPP publications as well as the final list of peptides transferred from PeptideAtlas to neXtProt denoted by red arrows. The green arrow shows publication of original studies subject to the HPP Guidelines v2.0 with data submitted to ProteomeXchange. Raw data, not published protein IDs, are required by PeptideAtlas and neXtProt.

The PeptideAtlas build process remains essentially the same as was reported last year.9 An exception is that the two uniquely mapping peptides of length ≥9 aa required to confer canonical status may no longer be fully nested (guideline 15).5 The reasoning is that, although having two peptides where one is nested within the other does confer additional confidence that the two peptide identifications are correct, it does not provide any additional evidence that the peptides are truly indicative of the claimed protein match and not a spurious association due to single amino acid variants (SAAV), isobaric post-translational modifications (PTM), or both.5

The neXtProt resource is the primary integrative knowledge base for the Human Proteome Project. It is sourced from UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot on an ongoing basis, meaning that changes made by Swiss-Prot curators are propagated periodically to neXtProt, which is updated 3 or 4 times per year. All UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot sequence entries, including alternative splice isoforms, are present in neXtProt, except for a set of ~130 immunoglobulins, which are excluded by neXtProt. For reference, in 2014 UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot added 40 new human proteins, and 117 were deprecated. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot categorizes each of its ~20,000 entries into five categories (levels 1–5) based on the evidence for protein existence (already defined. which neXtProt promotes if their curators find additional high-quality information (see Table 2, below). PE1 applies if there is strong evidence for detection of the protein from mass spectrometry or various other experimental methods. PE2 represents corresponding transcript expression without sufficient protein evidence. PE3 refers to evidence of homologous expression in nonhuman species but without even transcript evidence in human. PE4 reflects a predicted substantial likelihood of a translated product based on a consensus of gene modeling software predictions but without any other corroborating evidence. PE5 includes entries with a low likelihood of translation based on prediction but with some dubious evidence reported at the gene or protein level. In 2014 Lane et al.3 removed PE5 from the denominator of proteins to be discovered while allowing for appeals should new evidence be brought forward. Any changes made by neXtProt to the PE level, for example, based on PeptideAtlas evidence, are not back-propagated to UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, although neXtProt can nominate proteins for review by Swiss-Prot. All neXtProt content is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs License [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/].

Table 2.

neXtProt Computes a Protein Existence Status Based on Experimental Information from Multiple Types of Studies

| PE level | Sep 2013 | Oct 2014 | Apr 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. evidence at protein levela | 15,646 (78%)b | 16,491 (82%)b | 16,518 (85%)b |

| 2. evidence at transcript levelc | 3570 | 2647 | 2290 |

| 3. inferred from homologyc | 187 | 214 | 565 |

| 4. predictedc | 87 | 87 | 94 |

| 5. uncertain or dubious | 638 | 616 | 588 |

Clear experimental evidence for the existence of the protein, based on MS criteria (14,658), Edman sequencing (178), biochemical studies (299), PTMs (246), protein–protein interactions (659), antibody-based techniques (74), 3D structures (104), and disease mutations (253; untraceable MS data manually validated by Swiss-Prot curators); see green and yellow wedges in Figure 2.

Percent of predicted proteins classified as PE1 by neXtProt = PE1/PE1+2+3+4.

Missing.

It is important to note that the protein categories calculated by PeptideAtlas are not transferred to neXtProt; instead, all the distinct peptide identifications that pass the PeptideAtlas filters are transferred to neXtProt. NeXtProt uses the peptide evidence to independently determine PE1 categories, providing an independent check on the algorithms. However, one more subtle difference remains between PeptideAtlas and neXtProt: SAAVs are considered when determining peptide uniqueness by PeptideAtlas, but this is not (yet) done in neXtProt even though neXtProt has a very large documentation of SAAVs (see below). If a peptide maps to protein X in its reference form and to protein Y only when a catalogued SAAV is considered, it is still considered unique evidence for protein X by neXtProt, but not by PeptideAtlas, no matter how rare the SAAV might be.

GPMDB independently downloads data sets from PRIDE and MassIVE, but not from PASSEL, and receives some data sets directly from investigators. GPMDB has been operating since 2004. It checks ProteomeXchange, PRIDE, MassIVE, Pepti-deAtlas, Proteomics DB, the Chorus Project, and iProX daily for raw data sets suitable for reanalysis with its X!Tandem pipeline. Other data sets are collected directly from project Web sites. GPMDB is substantially larger than PeptideAtlas with 1056 publications cited as data sources and with 2.5 billion peptide–spectrum matches (PSMs) relative to 0.16 billion PSMs in PeptideAtlas; in contrast, only very high quality PSMs are retained in PeptideAtlas. The highest GPMDB Evidence Code EC4 is based on at least one peptide with a scoring distribution that exceeds a strict test for nonrandomness in the NBS v2 algorithm with ≥ 5 observations and skew and excess kurtosis both ≤ −1.5 or the weighted mean ≥ −5.5. These criteria are quite different from those of the new HPP Guidelines. The GPMDB Guide to the Human Proteome v21 has separate spreadsheets for each chromosome plus mitochondria; for example, Chr 17 has 1,175 gene entries and 6,432 splice protein entries. As shown in Figure 1, GPMDB does not exchange data with neXtProt.

There are several major differences between GPMDB and PeptideAtlas. Whereas GPMDB is built on Ensembl, the human PeptideAtlas is based primarily on neXtProt and secondarily on UniProt, Ensembl, and RefSeq; these sequence databases may be converging through use of GENCODE. GPMDB uses a reproducibility criterion for inclusion of proteins, requiring that a peptide or protein be identified at least five times. GPMDB has no special evaluation for reports of proteins that have not been observed previously; protein sequences have to be identified by at least one non-SAAV-containing peptide in the same data set for an SAAV-containing peptide to be recorded. GPMDB estimates that proteins based on a single report of two peptides of 9 aa might score only EC2 in GPMDB. Conversely, PeptideAtlas uses a parsimony rule, the basis for the class of 1755 “redundant proteins”, which excludes both proteins when two or more peptides match identically to both proteins; in contrast, GPMDB retains those paralogous or homologous proteins in the EC4 protein count, which presumably greatly contributes to the higher number of GPMDB proteins in Table 1 compared with the PeptideAtlas canonical proteins.

Table 1.

Numbers of Highly Confident Protein Identifications in neXtProt and Peptide Atlas for the 2016 HPP Annual Metrics

| chr. | neXtProt protein entries | neXtProt PE = 1 proteins | human PeptideAtlas (1% FDR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dec 2012 | all | 20,059 | 13,664 | 12,509 |

| Sep 2013 | all | 20,123 | 15,646 | 13,377 |

| Oct 2014 | all | 20,055 | 16,491 | 14,928 |

| Apr 2016 | all | 20,055 | 16,518a | 14,629 |

Using more stringent HPP MS Data Interpretation Guidelines v2.0, neXtProt excluded from PE1 485 proteins that would have been PE1 under the previous criteria: 432 now PE2, 40 PE3, and 7 PE4. PeptideAtlas canonical dropped from 14,928 to 14,070 with the use of Guidelines v2.0.

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA)12 has no mass spectrometry data; it is built on immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence from antibody profiling at the tissue and organelle levels together with extensive transcriptome information.

DISCUSSION

A year ago, the 2015 HPP Metrics paper4 introduced more stringent guidelines for accepting claims of identification of proteins from MS/MS data. This increased stringency was based on the experience of finding thousands of false-positive identifications for previously unreported proteins in published data sets.4 Even in PeptideAtlas there were cases of seemingly good matches for high-quality peptides that were better explained by variants or modifications of abundant proteins, especially when the identification was based on a single peptide or on short peptides of 7 or 8 aa. For PeptideAtlas, the major change adopted in 2015 was raising the threshold to two uniquely mapping peptides of nine or more amino acids in length; the details were presented in the PeptideAtlas 2015 paper9 along with the consequences for protein numbers, reducing the canonical list from 14,928 to 14,070 and increasing the numbers of redundant and uncertain proteins.

The canonical proteins figure has grown to 14,629 with new data sets incorporated into PeptideAtlas 2016-01, including most of the data sets from the 2015 JPR C-HPP third special issue and major phosphoprotein data sets from several laboratories (see below) captured in the new Human Phosphoproteome 2015-09 PeptideAtlas build [www.peptideatlas.org].

There has been a parallel progression to more stringent guidelines for protein evidence levels in neXtProt. For its 2015-03 update, neXtProt chose to use a combined threshold of two uniquely mapping peptides of ≥7 aa or one with ≤9 aa instead of accepting a single peptide of 7 or 8 aa. This step removed only 20 proteins. Accepting the new PeptideAtlas threshold of two peptides of ≥9 aa would have eliminated 432 proteins in the 2015-03 neXtProt release, as was documented in Supplementary Table S3.4

2016 Update of the HPP Metrics: neXtProt and PeptideAtlas

Table 1 shows the updated metrics for neXtProt and PeptideAtlas time points when the HPP metrics were assembled each year.

Table 2 shows the numbers of neXtProt proteins in each of the PE levels with the percentage of PE1+2+3+4 proteins identified as PE1.

From 20,055 predicted protein entries in neXtProt, 16,518 are now graded PE1 by neXtProt, very similar to the 16,491 seen last year. For neXtProt 2016-02, a bold decision was implemented to make the major neXtProt mass spectrometry criteria identical to those of PeptideAtlas. The result is the exclusion from PE1 status of 485 proteins that would have been PE1 under the previous guidelines due to the more stringent criteria for matching peptides to proteins (guideline 15).5 These 485 proteins are listed and substantially annotated in Supplementary Table 1. Now 438 are PE2 with transcripts, so their tissues of mRNA expression can provide a guide for where to search for additional protein level evidence; 40 are PE3 with informative homologous proteins in other species, and 7 are based on predictive models (PE4). The first 14 have disease associations, which might stimulate C-HPP or B/D-HPP teams to prioritize these missing proteins for disease studies. A great many have splice isoforms, sequence variants, and PTMs as listed. These 485 probably match fairly closely to the 449 labeled “uncertain” and PE2–4 in PeptideAtlas 2016-01 (see Table 3 below). The marked increase in the number of PE3 proteins in the February 2016 release of neXtProt over previous years is primarily due to the fact that UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot removed an upgrade to PE2 for entries that relied on inclusion in the ArrayExpress13 or CleanEx14 transcriptomics repositories.

Table 3.

Chromosome-by-Chromosome Status of PeptideAtlas for the C-HPP

| chromosome | neXtProt entries | canonical | % | uncertain | % | redundant | % | not observed | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2057 | 1512 | 74% | 121 | 6% | 162 | 8% | 262 | 13% |

| 2 | 1231 | 969 | 79% | 66 | 5% | 85 | 7% | 111 | 9% |

| 3 | 1071 | 830 | 78% | 43 | 4% | 67 | 6% | 131 | 12% |

| 4 | 761 | 577 | 76% | 41 | 5% | 60 | 8% | 83 | 11% |

| 5 | 869 | 654 | 75% | 56 | 6% | 64 | 7% | 95 | 11% |

| 6 | 1110 | 772 | 70% | 94 | 9% | 96 | 9% | 148 | 13% |

| 7 | 934 | 670 | 72% | 50 | 5% | 100 | 11% | 114 | 12% |

| 8 | 701 | 518 | 74% | 32 | 5% | 59 | 8% | 92 | 13% |

| 9 | 806 | 574 | 71% | 47 | 6% | 73 | 9% | 112 | 14% |

| 10 | 754 | 570 | 76% | 35 | 5% | 60 | 8% | 89 | 12% |

| 11 | 1324 | 854 | 65% | 57 | 4% | 148 | 11% | 265 | 20% |

| 12 | 1030 | 790 | 77% | 67 | 7% | 68 | 7% | 105 | 10% |

| 13 | 328 | 245 | 75% | 16 | 5% | 26 | 8% | 41 | 13% |

| 14 | 624 | 470 | 75% | 20 | 3% | 45 | 7% | 89 | 14% |

| 15 | 601 | 450 | 75% | 38 | 6% | 58 | 10% | 55 | 9% |

| 16 | 835 | 654 | 78% | 43 | 5% | 55 | 7% | 83 | 10% |

| 17 | 1168 | 890 | 76% | 73 | 6% | 87 | 7% | 118 | 10% |

| 18 | 275 | 215 | 78% | 11 | 4% | 17 | 6% | 32 | 12% |

| 19 | 1428 | 959 | 67% | 126 | 9% | 204 | 14% | 139 | 10% |

| 20 | 550 | 412 | 75% | 28 | 5% | 29 | 5% | 81 | 15% |

| 21 | 251 | 150 | 60% | 14 | 6% | 17 | 7% | 70 | 28% |

| 22 | 460 | 334 | 73% | 26 | 6% | 50 | 11% | 50 | 11% |

| X | 829 | 551 | 67% | 71 | 9% | 106 | 13% | 101 | 12% |

| Y | 48 | 5 | 10% | 11 | 23% | 19 | 40% | 13 | 27% |

| MT | 14 | 11 | 79% | 1 | 7% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 14% |

| ? | 5 | 1 | 20% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 80% |

|

| |||||||||

| PE | neXtProt entries | canonical | % | uncertain | % | redundant | % | not observed | % |

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | 16,518 | 14,569 | 88% | 700 | 4% | 583 | 4% | 666 | 4% |

| 2 | 2290 | 26 | 1% | 407 | 18% | 785 | 34% | 1072 | 47% |

| 3 | 565 | 5 | 1% | 36 | 6% | 209 | 37% | 315 | 56% |

| 4 | 94 | 0 | 0% | 6 | 6% | 13 | 14% | 75 | 80% |

| 5 | 588 | 29 | 5% | 38 | 7% | 165 | 28% | 356 | 61% |

| total | 20,055 | 14,629 | 1187 | 1755 | 2484 | ||||

It is important to recognize that there are many types of protein evidence besides mass spectrometry for this subset of PE1 proteins. Figure 2 shows that 14,658 PE1 proteins are based on the mass spectrometry results validated with two or more peptides of length 9 aa from PeptideAtlas, a number that closely matches the 14,629 canonical, even though neXtProt performs its assessment based on the peptides not the classification by PeptideAtlas. There are 1,860 PE1 proteins based on evidence other than MS, as noted in the Table 2 footnote, 2,464 “missing proteins” (PE2+3+4), lacking sufficient evidence for a confident identification plus 485 proteins excluded from PE1 by the more stringent criteria (above), making the total missing proteins 2,949, and the dubious PE5 category with 588 entries, approximately half pseudogenes, plus other untranslated elements that remain in Swiss-Prot and neXtProt but are candidates for future removal or, rarely, promotion. Peptides that seem to match to PE5 entries predominantly are shared with PE1 proteins. Lane et al.3 excluded PE5 from the denominator for estimates of percent missing proteins as we do in Table 2. The set of 485 neXtProt protein entries excluded may include many of the estimated 158 incorrect identifications (1% of canonical plus uncertain in Table 3 = 15,816) in PeptideAtlas.

Figure 2.

Basis for neXtProt protein existence PE1 evidence as well as for missing proteins in the human proteome. The green and yellow wedges have curated protein-level PE1 evidence; the red wedge represents the total of 2,949 missing proteins with PE2–4 evidence (see Table 2 and text).

Supplementary Figure 1 visualizes neXtProt results by PE levels for each chromosome, and Supplementary Table 2 presents the same information in a readable table with current numbers for each level for each chromosome. A search for tissue expression for the transcript-matching PE2 proteins remains manual, as there is no automated extraction of transcript or protein expression from Swiss-Prot and neXtProt annotations. neXtProt has released a new viewer of PE status per chromosome specifically dedicated to the C-HPP: https://search.nextprot.org/view/statistics/protein-existence.

Table 3 shows the detailed array of findings in PeptideAtlas with evidence classified as canonical, uncertain, redundant, or not observed, a classification explained in Deutsch et al.9 Proteins labeled uncertain can progress to canonical with sufficient additional findings; similarly, redundant protein matches might be differentiated with discovery from new studies of additional proteotypic/uniquely mapping peptides of 9 or more aa. Predicted proteins not observed might be searched for with knowledge of tissues in which transcripts have been found to be expressed in humans (PE2), as recorded in neXtProt or Human Protein Atlas. The same applies to PE3 proteins for which informative specimens were reported with high quality protein or genomic evidence in nonhuman species.

Of the total difference of 1,989 between 14,629 canonical proteins in PeptideAtlas 2016-01 and the 16,518 PE1 proteins in neXtProt-2016-02, 666 are not observed in PeptideAtlas (Table 3), and the rest are classified as uncertain or redundant. Of these 666, 24 are among the 247 with GO term “integral to membrane” and 28 are among the 476 with GO term “plasma membrane” when searched with PantherDB.15 Within “uncertain” is the noncanonical subcategory “indistinguishable representative”, referring to multiple protein matches from high-quality peptides; currently, there are 48 in PeptideAtlas 2016-01, of which 43 have at least two peptides. One is A8MRT5, whose two peptides map to 7 and 11 genomic locations.

2016 Update for GPMDB Guide to the Human Proteome v21

GPMDB 2016-01 has 16,190 EC4 proteins, up from 15,459 in 2014-07, 14,869 in 2013, and 14,300 in 2012. GPMDB updates more frequently than PeptideAtlas; it has more recent as well as many more data sets. See Workflow for a detailed discussion of features of GPMDB and contrasts with PeptideAtlas. See below for a description of the new g2pDB from GPMDB linking PTMs to coding sequences.

2016 Update for the Human Protein Atlas with Emphasis on the Testis Proteome

As reported last year, the HPA v13 was released in November 2014, and the tissue-based map of the Human Proteome was released in January 2015, accompanied by many tissue-based publications. HPA v14 was released on Oct 16, 2015 with the proteome analysis based on 25,039 antibodies targeting 17,005 unique proteins plus a transcriptome analysis of 217 tissue and cell line samples. Of the 17,005 predicted proteins targeted, the evidence based on immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence was classified as “supportive” for 10,475 compared with 12,007 supportive in the 2015 Metrics report.4 The main reason for this decrease in supportive protein evidence is that the database has been curated in comparison to transcriptome expression data across all tissues.

HPA v15 was released on Apr 11, 2016 containing the same protein data as v14. The major new feature of HPA v15 is the addition of GTEx transcriptome data. Tissue-enriched genes can be consistently defined in a genome-wide manner by the two independent data sets from HPA and GTEx generated using either fresh surgically removed tissues or post-mortem tissues taken within 24 h after the death of the individual.16 Another major release was the Atlas of the Mouse Brain, an interactive database with fluorescent images at cellular and subcellular levels, a “virtual microscope”.

Perhaps the most influential HPA release was the Testis Proteome, which revealed a stunning complement of 999 transcripts expressed at >5× the level of any other tissue.12,17 After removal of many proteins in the most recent Ensembl genome build (Ch38) and updating HPA to v15, 879 of those 999 proteins remained in Ensembl; the mapping of reads and the FPKM values were also affected with some transcript expression values falling below 1 FPKM. Supplementary Table 3 lists these 879 proteins with their ensg_id, gene name, UniProt_id, HPA protein evidence (supportive or uncertain), FKPM value in testis and tissue-specific score, the neXtProt PE level, and the classification of the protein in PeptideAtlas. Of the 879, only 354 are canonical in PeptideAtlas; the remainder of the list, especially those with substantial testis FKPM values, should be prime candidates for discovery by MS/MS in testis and/or sperm specimens. The table is in Excel format, permitting readers to choose features of interest.

A major development presented at the EuPA/C-HPP meeting in June 2016 and the HUPO Congress in September 2016 is the Antibody Validation Knockdown Initiative utilizing siRNA and CRISPR methods to knockout target proteins and provide negative controls for presumed target-specific antibodies. The HPA and HUPO HPP Antibody Resource Pillar are leaders of an international working group for antibody validation (IWGAV) whose objective is to develop new standards for validation of antibodies for both users and providers (M. Uhlén, chair). The Working Group is preparing a manuscript with guidelines to be posted on the HUPO Web site for comments from the general public, leading to revision, refinement, and review at the HUPO2016 Congress in Taipei in September 2016 and an Asilomar meeting in October 2016 with NIH and FASEB working groups, journals, and funders.

Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) of the Human Proteome

All of the major data resources for proteins have accumulated and annotated data for PTMs. Here we summarize what is available in PeptideAtlas, GPMDB, and neXtProt. The universe of PTMs is huge with estimates of more than 200 chemical classes of PTMs18 (www.uniprotkb.org/docs/ptmlist). The most prominent are S-, T-, and Y-phosphorylation, O- and N-glycosylation (many kinds of glycans), N-terminal and lysyl acetylation, ubiquitinylation and proteolytically processed proteoforms.

PeptideAtlas has presented a major increase in the number of observed PTMs with the release of the Human Phosphoproteome PeptideAtlas 2015-09. The build was assembled based on 143 samples enriched for phosphopeptides and yielded 128,000 phosphopeptides assigned to ~10,000 canonical proteins. All samples were searched using the usual PeptideAtlas methodology as referenced above with two key differences. First, all samples were searched with potential variable phosphorylation on the residues S, T, and Y. Second, all search results were processed with the TPP tool PTMProphet, which uses the peaks in each spectrum that can distinguish between different potential phosphosites to assign probabilities that the mass modifications are present at each potential site along with global false localization rates for the build.

Major contributions are from the Heck laboratory in The Netherlands19 (PXD001428) and the Mann laboratory in Munich20 (PXD000612). Giansanti et al.19 present data sets that were digested with several different proteases, demonstrating that greater coverage of the phosphoproteome was possible than when using trypsin alone. A total of 37,771 distinct phosphopeptides were identified, corresponding to over 18,000 distinct phosphosites. Remarkably, over two-thirds of these were identified via only one of the proteases they used. Sharma et al.20 reported ultradeep analysis revealing a distinct regulatory phenomenon in tyrosine- and serine/threonine-based signaling. The workflow to examine extent, localization, and site-specific stoichiometry analyzed phosphorylated peptides in a single human cancer cell line lysate, yielding 10,801 proteins of which 7,832 were phosphoproteins with 51K phosphopeptides and 38K phosphosites. Label-free quantitation showed very high stoichiometries in mitosis or growth factor signaling. p-Tyr is maintained at quite low levels in the absence of specific signaling events; it is enriched in higher-abundance proteins, correlating with substrate Km values of tyrosine kinases. Of comparative interest is another paper from the Mann lab,21 which describes EasyPhos, a scalable phosphoproteomics platform for rapid quantification of hundreds of phosphoproteomes in diverse cells and tissues at a depth of >10,000 sites applied to generate time-resolved maps of insulin signaling in the mouse liver. Insulin affects ~10% of the liver phosphoproteome. Many known functional phosphorylation sites, and even more unknown sites, are modified within 15 s after insulin delivery.

neXtProt has integrated PTM sites from 18 data sets covering different types of modifications: N- and O-glycosylation, sumoylation, ubiquitylation, nitrosylation, methylation, and more recently acetylation22 and ADP ribosylation.23 The total number of PTM sites documented is 142,281. Only high quality data are loaded, based on stringent criteria that vary from paper to paper, but that usually require a protein false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% or less. For each data set, a metadata file is provided, which documents experimental details and applied thresholds. neXtProt used to curate phosphorylation sites as well and had previously integrated data from six studies. For the 2016-02 release, neXtProt has replaced all the formerly curated phosphosites by those resulting from PeptideAtlas’ global analysis to limit the number of false positives. Conversely, neXtProt has provided extensive metadata for most of the 143 data sets included in the PeptideAtlas Human Phosphoproteome 2015-09 build.

UniProtKB highlighted the report of Bian et al.24 on the liver phosphoproteome, identifying 55,061 peptides for 22,446 phosphorylation sites in 6,526 different proteins. After reprocessing and assessment of their results according to stringent filtering rules, only 26,497 unique peptides were validated, and 5,197 phosphorylation sites were annotated in 4,118 UniProtKB/ Swiss-Prot entries.18

In February 2016, GPMDB published a new database, g2pDB, mapping protein post-translational modifications to protein modification acceptor sites and then to genomic coordinates. The information is accessible through a RESTful-style API to facilitate research by external users to determine which specific protein modifications would most likely be perturbed by particular nucleotide variants detected by DNA or RNA sequencing. Specifically for C-HPP investigators, Keegan25 has plotted histograms of the numbers of bases annotated on each human chromosome for S-, T-, and Y-phosphoryl, K-ubiquitinyl, and K-acetyl PTM acceptor sites. One of the features highlighted is that mapping these modifications to the DNA codon means that remapping for splice variants is not necessary. As of 2016-04, GPMDB contained the following numbers of sites for the PTMs most commonly investigated using MS/MS methods: 40,403 S-Phos, 10,805 T-Phos, 3422 Y-Phos, 7046 K-acetyl, and 25,175 K-ubiquitinylation. The numbers of codon bases mapped in g2pDB by the PTMs are three times these figures.25

Protein Proteoforms Defined by New Protein N and C Termini, a Ubiquitous PTM

A ubiquitous and functionally significant class of PTMs arises from proteolytic processing, which generates stable truncated proteoforms with new (neo-) N and/or C termini, the terminome. Their precise position and chemical nature determine functions in scheduling protein maturation, intracellular localization, receptor binding and activation, protein complex formation and disassembly, shedding, and turnover. Many PTMs of the N and C termini are annotated in TopFIND.26,27 NeXtProt lists 13,840 N terminal peptides starting at Met 1 or residue 2, making proteoform isoforms of 5,493 protein entries. Notably, there are 1,863 peptides representing 1,703 proteoforms of 921 proteins, as well as 305 of 201 proteins with transit peptides. Although less annotated, the C-terminus also displays great diversity with 13,009 proteoforms for 6,916 proteins, including only 27 proteins identified to date having a C-terminal propeptide identified. The task is immense to annotate the diverse proteoforms in the human proteome originating from alternate N and C termini, many of which may exhibit interesting variations in biological properties.

Overall and colleagues27 have developed degradomics with TAILS as a method to uniquely identify the cut ends of proteins by selectively purifying the semitryptic peptides of the natural and cleaved (neo) N and C termini from the remainder of a protein. The depletion of ~95% of the peptides generates a gain in sensitivity up to 5 orders of magnitude while analyzing peptides overlooked in standard shotgun analyses. Furthermore, the whole protein primary amine blocking (and labeling) step before trypsinization generates longer semi-ArgC peptides useful in seeking evidence for missing proteins, as reported for human dental pulp.28 The peptide numbers cited above all represent proteotypic peptides, thus showing the potential of terminomics to discover missing proteins. Identifying C-termini is difficult due to low chemical reactivity of carboxyl groups and lack of a basic residue after trypsin digestion. The trypsin mirroring Lysargi-Nase from the thermophilic archaea Methanosarcina acetivorans dramatically improves ionization and identification of protein C termini.29

Biomarker candidates arise from dysfunctionally regulated proteolytic processing in various diseases.29 Up to 44% of normal skin proteins feature different N termini than predicted from gene sequences. There are 565 known human proteases, of which only 340 have known substrates. Many can be expected to generate stable cleavage products exhibiting altered cell localization and functional properties.

SAAVs

neXtProt has now integrated 2.5 million SAAVs, and GPMDB has 2 million SAAVs; they are available for checking extraordinary claims for missing proteins or novel translation products as described in HPP Guideline 14.5 The SAAVs tracked by GPMDB are all based on dbSNP annotations, many of which are below the 1% threshold to be called “polymorphisms”. Variants can be accessed by splice-specific variant information, rs number, or all variants for a particular splice variant. There is a wide range of functional consequences from such variants. As described above, GPMDB has now created g2pDB to connect PTM sites in proteins with coding sequences in the DNA and its variants. One of the most popular algorithms for assessing the potential consequences of missense SNVs detected by next-generation sequences is Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT); SIFT uses multiple sequence alignment methods to determine whether a particular SAAV affects residues that have been found to be highly conserved in homologous proteins, as described by Keegan,25 together with several complementary methods.

Splice Isoforms

Splice isoforms are one of the most remarkable features of the evolution of multicellular organisms and multiexonic genes, involving elaborate and highly conserved spliceosome machinery that recognizes and removes introns (intervening sequences between exons). With approximately five splice isoform transcripts and proteins from each protein-coding gene, there must be a complex regulatory mechanism that governs, for instance, the differential expression of the isoforms from a particular gene in cancer relative to normal tissues.30

neXtProt documents splice isoforms with exactly the same splice variant sequences as in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot. There are, so far, very few functional annotations that are specific to a particular splice variant. It is feasible to predict functional differences between and among splice variants from the same gene using I-TASSER and other protein folding and ligand-binding algorithms.31 It is also feasible to predict isoform-level functional networks for the different splice isoforms of a given gene such as Her2/neu (ERBB2) using Hisonet32,33 and IsoFunc34 from http://guanlab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/.

neXtProt has the same listing of curated splice isoforms as UniProt with a total of 21,000 entries as of the 2016-02 release. GPMDB draws upon Ensembl, of which v84 has 102,000 protein accession numbers and 84,000 distinct sequences; the GPMDB Guide of 2016-01 provides lists of splice isoforms for every chromosome without a grand total based on Ensembl v76; as noted above, there are 6,432 splice isoform entries for Chr 17 (verified as of July 25, 2016).

Systematic Prediction of Proteins Unlikely to be Detectable by Mass Spectrometry

The Spanish Chr 16 Team (SpHPP) has undertaken an ambitious proteome-wide analysis that provides guidance for all the chromosome-based groups on how to strategically search for missing proteins.35 The project starts with the observation that a fundamental goal of genome research is the generation of a protein-coding catalog with knowledge of protein functions, regulatory mechanisms, networks of interaction, abundance, isoform patterns, and dynamics in health and disease, matching very closely the overall goal of the Human Proteome Project. The pipeline predicts the probability of a missing protein being expressed in a specific biological sample based on gene sequence characteristics, the probability of an expressed gene being a coding gene of a missing protein in a certain sample, and the probability of a gene being expressed in a transcriptomic experiment. They analyzed >3,400 microarray experiments on 917 cell lines from 36 cancer types, 353 samples from 65 normal tissues from 10 post-mortem donors, and 2,158 tumor samples from 156 tissues/cell lines. Data were obtained on 2,865 Ensembl genes among the 3,923 neXtProt 2013-10 missing proteins. Genes were classified with a naïve Bayes classifier based on transcript expression, 3′ UTR and 5′ UTR lengths, and CDS gene sequence lengths as ubiquitous, nonubiquitous, nonex-pressed, and coding genes of missing proteins. In addition, a tissue-specific expression pattern for coding genes of missing proteins was reported. A separate analysis of underrepresented specimens led to identification of testis, brain, and skeletal muscle as promising normal tissues for finding missing proteins.36

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND NEW DIRECTIONS

The progress on completing the parts list of the Human Proteome continues, though PeptideAtlas and neXtProt have noted a slowing of the rate of increase, as documented in Table 1. The neXtProt 16,518 PE1 proteins represent 85% of the 19,467 PE1–4 entries; the PA 14,629 canonical number represents 75%. A major part of this slowing in the finding of more of the missing proteins is due to the more stringent HPP criteria for quality control in response to the recognition of a high propensity for false-positive identifications in simply automated identification of peptide to protein matches; large numbers of reported proteins are noncanonical, called uncertain (1187) or redundant (1755) in PeptideAtlas 2016-01 (see Table 3).

A deeper reason for the slowing is the strong likelihood that roughly 10–15% of predicted proteins either are not expressed or are hard to detect by current solubilization, proteolysis, and MS/MS methods. If DNase I hypersensitivity experiments show that the chromosomal region of certain genes or families of genes is inaccessible for transcription, then neither transcripts nor proteins will be produced; this circumstance has been very well demonstrated for beta-defensins as well as their chromosomal neighbors. Wang et al.37 reported in the C-HPP 2015 special issue that 13 beta-defensin genes located on chromosome 20 were detected in neither mRNA nor protein in several cell lines and tissues. Liu et al.38 made the same observation for the beta-defensin genes located on chromosome 8, except the commonly detected DEFB1. Extensive data were available from the ENCODE project to examine the chromatin features for transcription factor access. Kong et al.39 used ENCODE data to contrast chromosome 11, which has the lowest proportion, and chromosome 19, which has the highest proportion of detected mRNAs; chromosome 19 is lowest and chromosome 11 highest for missing proteins from protein-coding genes. They confirmed that such divergent detection rates were independent of cell type and tissue in the HPA. Poor transcription of missing protein genes reflects low transcription factor binding and weak histone modifications in these chromatin regions.

If no tryptic peptides of 9–30 amino acids in length are generated from the protein sequence, trypsin-based MS/MS analyses will not find these predicted proteins; similarly, if the protein is highly hydrophobic and/or embedded in membranes, detection will be difficult, requiring better solubilization and/or different proteolytic enzymes.

The testis has been highlighted as a tissue with multiple compartments and a very large number of tissue-specific or tissue-highly enriched transcripts and proteins. C-HPP teams have begun examining testis in depth. Jumeau et al.40 (PXD002367) reported finding 89 missing proteins from human spermatozoa. Zhang et al.41 (PXD002179) identified 166 missing protein groups in testis. In Supplementary Table 3, we show that only 354 of the 879 HPA testis-enriched proteins are canonical in PeptideAtlas, leaving 525 yet to be found even after these two data sets were incorporated into PeptideAtlas 2016-01. In this JPR issue, follow-up papers from each of those groups extend these findings with 206 additional missing proteins from sperm (Vandenbrouck et al.,42 PXD003947) and 47 additional missing proteins from testis (Wei et al.,43 iProx00076500) identified under the new guidelines. In addition, Duek et al.44 have presented an outstanding analysis of chromosomes 2 and 14 for missing proteins, theoretically detectable proteins, and proteins most promising for SRM analysis in sperm.

Another aspect of the HPP, clearly stated from the start in the first goal about the protein parts list, is the identification and characterization of the many proteoforms of each protein comprising sequence variants, post-translational modifications, and splice isoforms. We have documented tremendous progress in the databases described above and in biological studies in the literature.

Separately, the B/D-HPP will report on its recent activities.45 The B/D-HPP has created comprehensive SRM resources,46 generated priority-protein/popular-protein lists to guide targeted proteomics assays for specific diseases47, and launched an Early Career Researchers initiative.

Finally, the second overarching goal of the HPP is to make proteomics more visible and more commonly integrated with other omics platforms for more informative biological studies. For example, proteomics has now become a major component of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project. Even broader is the objective of making proteomics better known to the general public. This year, a remarkable development along these lines has been the crowd-sourcing experiment of the HPA, Project Discovery, in which citizen scientists, especially students, refine the HPA annotations for proteins within various cellular structures, such as the nucleolus, for which the rim and the fibrillar center were labeled in A-431 cells of human epidermoid carcinoma [see Image of the Week, April 8, 2016]. This community-based project is likely to significantly enhance the appreciation of proteomics and the human proteome. Project Discovery is presented by EVE Online, the largest sci-fi Massively Multiplayer Online Science (MMOS) game, stimulating players to contribute to scientific advancement Launched March 9, 2016; over 25,000 people played the first week and together provided 2.2 million image classifications. Players join through the Sisters of Eve. Led by Emma Lundberg, the HPA team is crunching the data. The HPP is committed to helping encourage students and others to try the game and experience scientific discovery firsthand while helping the HPA team refine the Human Protein Atlas. [Project Discovery Web site: http://www.eveonline.com/discovery/. Media coverage: http://www.ibtimes.com/play-eve-online-science-gamers-classify-proteins-earn-game-rewards-project-discovery-2333975.] A complementary project is Planet Hunters, which briefly trained volunteers to look for the telltale sign of a dip in brightness when a planet passes in front of a star, tied to the Kepler Space Telescope, which has discovered planet candidates outside our solar system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the guidance and comments from Amos Bairoch of neXtProt and the HPP Executive Committee. We thank the UniProt groups at SIB, EBI, and PIR for their dedication in providing up-to-date high-quality annotations for the human proteins in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, thus providing neXtProt with a solid foundation. neXtProt development benefits from extensive funding support from the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. The neXtProt server is hosted by VitalIT, the bioinformatics competence center that supports and collaborates with life scientists in Switzerland. We thank Åsa Sivertsson of the SciLife Lab and the Human Protein Atlas for providing Supplementary Table 3 from studies of the human testis proteome and HUPO President Mark Baker for suggestions about Figure 1. G.S.O. acknowledges grant support from National Institutes of Health grant P30ES017885, E.W.D. from NIH grants R01GM087221 and U54EB020406, and E.K.L. from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and EU 7th Framework.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

- The 485 proteins that would have qualified for PE1 in neXtProt under guidelines version 1.0 which have been excluded in neXtProt 2016-02 under HPP guidelines version 2.0 (XLS)

- The 2,949 PE2,3,4 missing proteins in neXtProt 2016-02 (XLSX)

- Chromosome-by-chromosome list of numbers of neXt-Prot entries by PE level (XLSX)

- Human Protein Atlas 2016-05 list of the 879 testis-specific or testis-enriched proteins (XLSX)

- Circular chart showing proportions of protein-coding genes on each chromosome by neXtProt PE level (PDF)

References

- 1.Legrain P, Aebersold R, Archakov A, Bairoch A, Bala K, Beretta L, Bergeron J, Borchers CH, Corthals GL, Costello CE, Deutsch EW, Domon B, Hancock W, He F, Hochstrasser D, Marko-Varga G, Salekdeh GH, Sechi S, Snyder M, Srivastava S, Uhlen M, Wu CH, Yamamoto T, Paik YK, Omenn GS. The Human Proteome Project: current state and future direction. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(7):M111 009993. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marko-Varga G, Omenn GS, Paik YK, Hancock WS. A first step toward completion of a genome-wide characterization of the human proteome. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(1):1–5. doi: 10.1021/pr301183a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane L, Bairoch A, Beavis RC, Deutsch EW, Gaudet P, Lundberg E, Omenn GS. Metrics for the human proteome project 2013–2014 and strategies for finding missing proteins. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(1):15–20. doi: 10.1021/pr401144x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omenn GS, Lane L, Lundberg EK, Beavis RC, Nesvizhskii AI, Deutsch EW. Metrics for the Human Proteome Project 2015: progress on the human proteome and guidelines for high-confidence protein identification. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3452–60. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutsch EW, Overall CM, Van Eyk J, Baker M, Paik YK, Weintraub S, Lane L, Martens L, Vandenbrouck Y, Kusebauch U, Hancock W, Hermjakob H, Aebersold R, Moritz RL, Omenn GS. Human Proteome Project mass spectrometry data interpretation guidelines 2.1. J Proteome Res. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteo-me.6b00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vizcaino JA, Deutsch EW, Wang R, Csordas A, Reisinger F, Rios D, Dianes JA, Sun Z, Farrah T, Bandeira N, Binz PA, Xenarios I, Eisenacher M, Mayer G, Gatto L, Campos A, Chalkley RJ, Kraus HJ, Albar JP, Martinez-Bartolome S, Apweiler R, Omenn GS, Martens L, Jones AR, Hermjakob H. ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(3):223–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vizcaino JA, Csordas A, del-Toro N, Dianes JA, Griss J, Lavidas I, Mayer G, Perez-Riverol Y, Reisinger F, Ternent T, Xu QW, Wang R, Hermjakob H. 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D447–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrah T, Deutsch EW, Kreisberg R, Sun Z, Campbell DS, Mendoza L, Kusebauch U, Brusniak MY, Huttenhain R, Schiess R, Selevsek N, Aebersold R, Moritz RL. PASSEL: the PeptideAtlas SRM experiment library. Proteomics. 2012;12(8):1170–5. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsch EW, Sun Z, Campbell D, Kusebauch U, Chu CS, Mendoza L, Shteynberg D, Omenn GS, Moritz RL. State of the human proteome in 2014/2015 as viewed through PeptideAtlas: Enhancing accuracy and coverage through the AtlasProphet. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3461–73. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keller A, Eng J, Zhang N, Li XJ, Aebersold R. A uniform proteomics MS/MS analysis platform utilizing open XML file formats. Mol Syst Biol. 2005;1:2005.0017. doi: 10.1038/msb4100024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutsch EW, Mendoza L, Shteynberg D, Slagel J, Sun Z, Moritz RL. Transproteomic pipeline, a standardized data processing pipeline for large-scale reproducible proteomics informatics. Proteomics: Clin Appl. 2015;9(7–8):745–54. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson A, Kampf C, Sjostedt E, Asplund A, Olsson I, Edlund K, Lundberg E, Navani S, Szigyarto CA, Odeberg J, Djureinovic D, Takanen JO, Hober S, Alm T, Edqvist PH, Berling H, Tegel H, Mulder J, Rockberg J, Nilsson P, Schwenk JM, Hamsten M, von Feilitzen K, Forsberg M, Persson L, Johansson F, Zwahlen M, von Heijne G, Nielsen J, Ponten F. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419-1–1260419-9. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parkinson H, Sarkans U, Shojatalab M, Abeygunawardena N, Contrino S, Coulson R, Farne A, Lara GG, Holloway E, Kapushesky M, Lilja P, Mukherjee G, Oezcimen A, Rayner T, Rocca-Serra P, Sharma A, Sansone S, Brazma A. ArrayExpress–a public repository for microarray gene expression data at the EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D553–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Praz V, Jagannathan V, Bucher P. CleanEx: a database of heterogeneous gene expression data based on a consistent gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D542–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mi H, Poudel S, Muruganujan A, Casagrande JT, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 10: expanded protein families and functions, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D336–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhlen M, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Mardinoglu A, Ponten F, Nielsen J. Transcriptomics resources of human tissues and organs. Mol Syst Biol. 2016;12(4):862. doi: 10.15252/msb.20155865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djureinovic D, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom B, Danielsson A, Lindskog C, Uhlen M, Ponten F. The human testis-specific proteome defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20(6):476–88. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breuza L, Poux S, Estreicher A, Famiglietti ML, Magrane M, Tognolli M, Bridge A, Baratin D, Redaschi N. The UniProtKB guide to the human proteome. Database. 2016;2016:bav120. doi: 10.1093/database/bav120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giansanti P, Aye TT, van den Toorn H, Peng M, van Breukelen B, Heck AJ. An augmented multiple-protease-based human phosphopeptide atlas. Cell Rep. 2015;11(11):1834–43. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma K, D’Souza RC, Tyanova S, Schaab C, Wisniewski JR, Cox J, Mann M. Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;8(5):1583–94. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphrey SJ, Azimifar SB, Mann M. High-throughput phosphoproteomics reveals in vivo insulin signaling dynamics. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(9):990–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun G, Jiang M, Zhou T, Guo Y, Cui Y, Guo X, Sha J. Insights into the lysine acetylproteome of human sperm. J Proteomics. 2014;109:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Wang J, Ding M, Yu Y. Site-specific characterization of the Asp- and Glu-ADP-ribosylated proteome. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):981–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bian Y, Song C, Cheng K, Dong M, Wang F, Huang J, Sun D, Wang L, Ye M, Zou H. An enzyme assisted RP-RPLC approach for in-depth analysis of human liver phosphoproteome. J Proteomics. 2014;96:253–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keegan S, Cortens JP, Beavis RC, Fenyo D. g2pDB: A database mapping protein post-translational modifications to genomic coordinates. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(3):983–90. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange PF, Overall CM. TopFIND, a knowledgebase linking protein termini with function. Nat Methods. 2011;8(9):703–4. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marino G, Eckhard U, Overall CM. Protein termini and their modifications revealed by positional proteomics. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(8):1754–64. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckhard U, Marino G, Abbey SR, Tharmarajah G, Matthew I, Overall CM. The human dental pulp proteome and N-Terminome: Levering the unexplored potential of semitryptic peptides enriched by TAILS to identify missing proteins in the Human Proteome Project in underexplored tissues. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3568–82. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huesgen PF, Lange PF, Rogers LD, Solis N, Eckhard U, Kleifeld O, Goulas T, Gomis-Ruth FX, Overall CM. LysargiNase mirrors trypsin for protein C-terminal and methylation-site identification. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):55–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omenn GS. Plasma Proteomics, The Human Proteome Project, and cancer-associated alternative splice variant proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2014;1844(5):866–873. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menon R, Roy A, Mukherjee S, Belkin S, Zhang Y, Omenn GS. Functional implications of structural predictions for alternative splice proteins expressed in Her2/neu-induced breast cancers. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(12):5503–11. doi: 10.1021/pr200772w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Menon R, Govindarajoo B, Panwar B, Zhang Y, Omenn GS, Guan Y. Functional networks of highest-connected splice isoforms, from the Chromosome 17 human proteome project. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3484–91. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao X, Liu Y, Li Y, Xian M, Zhou Q, Yang B, Ying M, He Q. The HER2 inhibitor TAK165 sensitizes human acute myeloid leukemia cells to retinoic acid-induced myeloid differentiation by activating MEK/ERK mediated RARalpha/STAT1 axis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24589. doi: 10.1038/srep24589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panwar B, Menon R, Eksi R, Li HD, Omenn GS, Guan Y. Genome-wide functional annotation of human protein-coding splice variants using multiple instance learning. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(6):1747–53. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guruceaga E, Sanchez del Pino MM, Corrales FJ, Segura V. Prediction of a missing protein expression map in the context of the human proteome project. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(3):1350–60. doi: 10.1021/pr500850u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrah T, Deutsch EW, Omenn GS, Sun Z, Watts JD, Yamamoto T, Shteynberg D, Harris MM, Moritz RL. State of the human proteome in 2013 as viewed through PeptideAtlas: comparing the kidney, urine, and plasma proteomes for the biology- and disease-driven human proteome project. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(1):60–75. doi: 10.1021/pr4010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Q, Wen B, Wang T, Xu Z, Yin X, Xu S, Ren Z, Hou G, Zhou R, Zhao H, Zi J, Zhang S, Gao H, Lou X, Sun H, Feng Q, Chang C, Qin P, Zhang C, Li N, Zhu Y, Gu W, Zhong J, Zhang G, Yang P, Yan G, Shen H, Liu X, Lu H, Zhong F, He QY, Xu P, Lin L, Liu S. Omics evidence: single nucleotide variants transmissions on chromosome 20 in liver cancer cell lines. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(1):200–11. doi: 10.1021/pr400899b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Ying W, Ren Z, Gu W, Zhang Y, Yan G, Yang P, Liu Y, Yin X, Chang C, Jiang J, Fan F, Zhang C, Xu P, Wang Q, Wen B, Lin L, Wang T, Du C, Zhong J, Wang T, He QY, Qian X, Lou X, Zhang G, Zhong F. Chromosome-8-coded proteome of Chinese chromosome proteome data set (CCPD) 2.0 with partial immunohistochemical verifications. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(1):126–36. doi: 10.1021/pr400902u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong N, Zhou Y, Xu S, Deng Y, Fan Y, Zhang Y, Ren Z, Lin L, Ren Y, Wang Q, Zi J, Wen B, Liu S. Assessing transcription regulatory elements to evaluate the expression status of missing protein genes on chromosomes 11 and 19. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(12):4967–75. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jumeau F, Com E, Lane L, Duek P, Lagarrigue M, Lavigne R, Guillot L, Rondel K, Gateau A, Melaine N, Guevel B, Sergeant N, Mitchell V, Pineau C. Human spermatozoa as a model for detecting missing proteins in the context of the Chromosome-Centric Human Proteome Project. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3606–20. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Li Q, Wu F, Zhou R, Qi Y, Su N, Chen L, Xu S, Jiang T, Zhang C, Cheng G, Chen X, Kong D, Wang Y, Zhang T, Zi J, Wei W, Gao Y, Zhen B, Xiong Z, Wu S, Yang P, Wang Q, Wen B, He F, Xu P, Liu S. Tissue-based proteogenomics reveals that human testis endows plentiful missing proteins. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):3583–94. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vandenbrouck Y, Lane L, Carapito C, Duek P, Rondel K, Bruley C, Macron C, Gonzalez de Peredo A, Coute Y, Chaoui K, Com E, Gateau A, Hesse AM, Marcellin M, Mear L, Mouton-Barbosa E, Robin T, Burlet-Schiltz O, Cianferani S, Ferro M, Freour T, Lindskog C, Garin J, Pineau C. Looking for missing proteins in the proteome of human spermatozoa: an update. J Proteome Res. 2016;(this issue) doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei W, Luo W, Wu F, Peng X, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Zhao Y, Su N, Qi Y, Chen L, Zhang Y, Wen B, He F, Xu P. Deep coverage proteomics identifies more low-abundance missing proteins in human testis tissue with Q-exactive HF mass spectrometer. 2016;(this issue) doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duek P, Bairoch A, Gateau A, Vandenbrouck Y, Lane L. The missing protein landscape of human Chromosomes 2 and 14: Progress and current status. J Proteome Res. 2016;(this issue) doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Eyk J, Corrales FJ, Aebersold R, Cerciello F, Deutsch EW, Roncada P, Sanchez JC, Yamamoto T, Yang P, Zhang H, Omenn GS. J Proteome Res; Highlights of the Biology and Disease-driven Human Proteome Project Workshops at the 15th Annual HUPO World Congress in Vancouver; Canada. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kusebauch U, Campbell DS, Deutsch EW, Chu CS, Spicer DA, Brusniak MY, Slagel J, Sun Z, Stevens J, Grimes B, Shteynberg D, Hoopmann MR, Blattmann P, Ratushny AV, Rinner O, Picotti P, Carapito C, Huang CY, Kapousouz M, Lam H, Tran T, Demir E, Aitchison JD, Sander C, Hood L, Aebersold R, Moritz RL. Human SRMAtlas: A resource of targeted assays to quantify the complete Human Proteome. Cell. 2016;166(3):766–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lam M, Xing Y, Lau E, Cao Q, Ng D, Su A, Ge J, Van Eyk J, Ping P. Data-driven approach to determine popular proteins for targeted proteomics translation. J Proteome Res. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00095. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.