Abstract

The Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an arrhythmogenic disease associated with an increased risk of ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death. The risk stratification and management of BrS patients, particularly of asymptomatic ones, still remains challenging. A previous history of aborted sudden cardiac death or arrhythmic syncope in the presence of spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern of BrS phenotype appear to be the most reliable predictors of future arrhythmic events. Several other ECG parameters have been proposed for risk stratification. Among these ECG markers, QRS-fragmentation appears very promising. Although the value of electrophysiological study still remains controversial, it appears to add important information on risk stratification, particularly when incorporated in multiparametric scores in combination with other known risk factors. The present review article provides an update on the pathophysiology, risk stratification and management of patients with BrS.

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, risk stratification, electrophysiological study, sudden cardiac death

Introduction

The Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited arrhythmogenic disease characterized by ST-segment elevation in right precordial leads on surface electrocardiogram (ECG), the absence of overt structural heart disease, and an increased risk of ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac death (SCD).[1-5] There is increasing evidence suggesting that mild structural abnormalities seen in the right ventricular outflow tract provide the arrhythmia substrate in BrS.[2,6,7] The BrS is definitively diagnosed when a type 1 ST-segment elevation (coved type) ≥2 mm is observed either spontaneously or after intravenous administration of a sodium channel blocking agent (ajmaline, flecainide, procainamide or pilsicainide) in at least one right precordial lead (V1 and V2), which are placed in a standard or a superior position (up to the 2nd intercostal space).[8] The BrS is a genetically heterogeneous channelopathy. Up to now, mutations in 19 genes have been identified in subjects with BrS phenotype.[4] These mutations cause either a decrease in inward sodium or calcium current or an increase in outward potassium currents resulting in an outward shift in the balance of current active during the early phases of the action potential.[4]

The BrS typically manifests with cardiac arrest or syncope, occurring in the third and fourth decade of life.[3-5] The majority of BrS patients are asymptomatic, usually diagnosed incidentally. The risk stratification of BrS patients, and particularly of asymptomatic ones, still remains challenging. Currently, subjects with spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern and aborted SCD or syncope of arrhythmic origin are at highest risk for future arrhythmic events, and are advised to receive an the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).[3-5] Emerging evidence clearly underscore our inability to stratify patients with BrS.[9] Several markers has been proposed for risk stratification, but the majority of them have not been tested in a prospective manner. The present study focus on current risk stratification markers as well as on the management of high risk BrS patients.

Risk Stratification Of Individuals With Brugada Syndrome

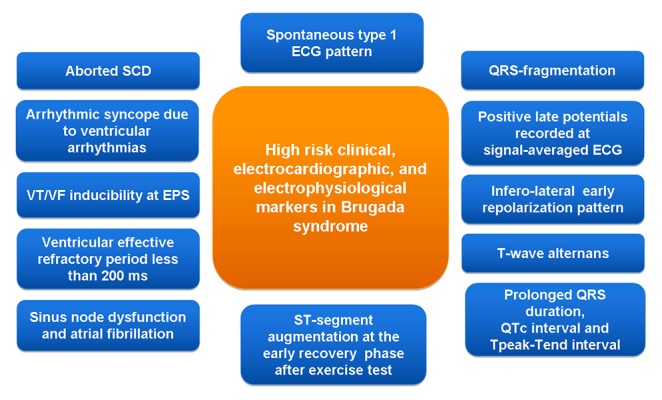

It is widely accepted that symptomatic BrS patients are at increased risk for future events.[4,5] However, in a post-mortem study, the majority of SCDs related to BrS occurred in asymptomatic individuals (72%). Based on the Second Expert Consensus Conference on BrS,[3] 68% of this population would have been categorized as low risk.[9] Asymptomatic BrS patients display an annual event rate of arrhythmic events between 0.5 and 1%.[10-12] This event will occur in about 50% of cases as VF without any warning symptoms.[13] Although, it is currently impossible to estimate the evolution of arrhythmic risk over time, assuming an annual event rate of 1%, a 10% event rate at 10-year follow-up in otherwise healthy patients is extremely high. Proper risk stratification of BrS patients, particularly of asymptomatic ones, is therefore of paramount importance. Several clinical, echocardiographic, electrocardiographic and electrophysiological markers have been proposed as risk stratifiers (figure 1).

Figure 1: Clinical, electrocardiographic and electrophysiological markers proposed for risk stratification in BrS.

Clinical Markers

A history of aborted SCD has been consistently associated with the highest risk of future arrhythmic events in all studies, and thus has a major prognostic impact.[10-12,14-20] In a recent meta-analysis, the incidence of arrhythmic events (sustained ventricular arrhythmia or appropriate ICD therapy or SCD) was 13.5% per year in patients with a history of SCD, 3.2% per year in patients with syncope and 1% per year in asymptomatic patients.[21] The arrhythmic risk among patients with a history of aborted SCD is 35% at 4 years,[10,15] 44% at 7 years,12 and 48% at 10 years.[21]

A history of syncope has been associated with an increased incidence of future arrhythmic events in several studies, including a meta-analysis.[10,11,14,16-23] However, Priori’s group have initially demonstrated that the association of syncope and spontaneous ST-segment elevation has the best predictive value to identify individuals at high risk, and not a history of syncope as a single risk factor.[24] Kamakura et al. showed that patients presenting with aborted SCD had a grim prognosis, while those presenting with syncope or no symptoms had an excellent prognosis irrespective of their ECG pattern.[15] Conte et al. from P. Brugada’s group have recently demonstrated that patients with a history of syncope display a similar clinical course with asymptomatic ones. In particular, 11% of patients with syncope and 13% of asymptomatic subjects received appropriate shocks during a long term follow-up period of 83.8 ± 57.3 months.[12] This inconsistency possibly reflects our difficulty to differentiate arrhythmic from neurally-mediated syncope. A high incidence of neurally-mediated susceptibility in asymptomatic individuals with BrS ECG pattern has been previously shown.[25] In Conte’s study, after ICD placement, 21 patients (11.9%) experienced episodes of syncope. Of them, 5 patients had neurally-mediated syncope. In 8 patients with recurrent syncope after ICD implantation, the rate of ventricular pacing was <1%, and no ventricular arrhythmias were detected.[25] This possibly explains why some patients with a previous history of undetermined syncope display an excellent prognosis.

The majority of large studies on BrS have demonstrated that a family history of SCD is not predictive of future arrhythmic events.[10,12,1,26] In the largest registry, a family history of SCD was not predictive of arrhythmic events in either symptomatic (3.3% vs. 3.0%) or asymptomatic patients (0.5% vs. 0.6%).[10] On the contrary, Kamakura et al. have demonstrated that a family history of SCD occurring at age <45 years is an independent risk factor of poor prognosis irrespective of ECG type. Delise et al. have shown that family history of SCD may be of prognostic significance only in combination with other risk factors.[17]

In a previous meta-analysis accumulating data on 1.545 patients, male gender has been associated with a malignant clinical course.[20] In FINGER registry, male gender tended to be associated with a shorter time to first event, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (mean event rate per year, 3.0% for men versus 0.9% for women).[10] Similarly, in Conte’s study, males displayed a near 3-fold higher risk for appropriate shocks during follow-up.[12] Data from S. Priori’s group showed that there is a non-significant excess of events in males (13%) as opposed to females (9%).[24] These data suggest that females with BrS ECG pattern should not be regarded as a low risk group.

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in BrS patients is higher than in the general population of the same age. In a large study of 560 BrS patients, 48 (9%) had atrial fibrillation/flutter.18 In 176 BrS patients with an ICD, 18% of patients developed paroxysmal AF during a long-term follow-up period of 83.8 ± 57.3 months.[12] A higher incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmias (fibrillation/flutter) (24%) has been demonstrated in our BrS series.[27] Spontaneous atrial fibrillation has been associated with higher incidence of syncopal episodes (60.0% vs. 22.2%) and documented VF (40.0% vs. 14.3%). In patients with documented VF, higher incidence of spontaneous atrial fibrillation (30.8% vs. 10.0%, p < 0.05), atrial fibrillation induction (53.8% vs. 20.0%), and prolonged interatrial conduction time was observed.[28] Siera et al. have recently reported that asymptomatic BrS subjects with history of sinus node dysfunction display an 8-fold increased risk for future arrhythmic events.[29]

Genetic Markers

A genetic defect on the SCN5A gene has not been associated with a higher risk of future arrhythmic events in several studies, suggesting that genetic analysis is a useful diagnostic parameter but it is not helpful for risk stratification.[10-12,24,26]

Echocardiographic Markers

A reduced right ventricular ejection fraction and an increased right ventricular end-diastolic volume were independently associated with history of syncope or SCD at the time of diagnosis.[30] Using tissue velocity imaging, Van Malderen et al. have demonstrated that a previous history of malignant events is associated with prolonged right ventricular ejection delay.[31]

Electrocardiographic Markers

A spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern of BrS has been consistently associated with a worse outcome in large studies,[10-12] and thus should be considered as a malignant marker. A meta-analysis showed that individuals with spontaneous type 1 ECG features exhibit a 3- to 4-fold increased risk of events compared to those with a drug-induced ECG pattern.[20] We recently demonstrated that asymptomatic subjects with spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern of BrS exhibit a 3.5 higher risk of future arrhythmic events.[32] It is therefore very important to establish or not the presence of spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern in BrS patients. In patients with drug-induced type 1, spontaneous type 1 BrS can be more frequently detected with twelve lead Holter monitoring compared with conventional follow-up with periodic ECGs. Twelve lead Holter recording might avoid 20% of the pharmacological challenges with sodium channel blockers, which are not without risks, and should thus be considered as the first screening test, particularly in children or in the presence of borderline diagnostic basal ECG.[33]

Apart from the spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern, several other ECG parameters have been proposed for risk stratification of subjects with BrS phenotype. Among these ECG markers, QRS-fragmentation in twelve-lead ECG appears very promising. Morita et al. have initially demonstrated that QRS-fragmentation is more commonly seen in BrS patients with VF (85%) and syncope (50%) compared to asymptomatic ones (34%).[34] The PRELUDE study confirmed these findings and showed that QRS-fragmentation is an independent predictor of future arrhythmias.[11] Tokioka et al. have recently demonstrated that the presence of QRS-fragmentation lead to a 5-fold increase of arrhythmic events.[23] A prospective study using signal-averaged ECG suggested that positive late potentials may have predictive value of malignant arrhythmic events in BrS.[35] Ajiro et al. have showed that symptomatic subjects with BrS display significantly lower RMS40, longer LAS40, and longer filtered QRS duration compared to the asymptomatic ones.[36] The positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and predictive accuracy of late potentials were 92.0%, 78.9%, and 86.4%, respectively. Daily fluctuations in ECG and SAECG characteristics could be useful for distinguishing between high- and low-risk patients with BrS.[37]

First degree atrioventricular block has been independently associated with SCD or appropriate ICD therapies.[38] A prolonged QRS duration in leads II, V2 and V6[39,40] as well as a prolonged QTc interval >460 ms in lead V241 have been associated with life-threatening arrhythmic events in BrS. The Tpeak-Tend interval, a marker of transmural dispersion of repolarization, has been linked to malignant ventricular arrhythmias in various clinical settings including the BrS. Castro Hevia et al. were the first to link increased Tpeak-Tend interval as a risk factor in patients with BS.[41] Maury et al. has been recently demonstrated that the Tpeak-Tend interval from lead V1 to lead V4, the maximum value of the Tpeak-Tend interval, and the Tpeak-Tend interval dispersion in all precordial leads were significantly higher in symptomatic patients (aborted SCD, appropriate ICD therapy, syncope) than in asymptomatic patients. In multivariate analysis, a max Tpeak-Tend of >100 ms was independently related to arrhythmic events.[38] We have previously shown that the Tpeak-Tend interval and Tpeak-Tend interval/QT ratio were associated with VT/VF inducibility in BrS.[42] A more negative T-wave in lead V1 has been also associated with poor prognosis.[43] Finally, the appearance of T-wave alternans after pilsicainide administration was predictive for spontaneous VF.[44]

Masrur et al. performed a systematic review including 166 BrS patients undergoing exercise testing.[45] ST-segment augmentation was observed in 95 of 166 (57%) BrS patients. The ST augmentation occurred during early recovery after exercise in 93 Brugada patients, whereas 2 patients developed ST augmentation during the effort phase of exercise. Exercise unmasked the BrS ECG pattern in 5 patients. Three patients developed ventricular arrhythmias with exercise: 2 developed ventricular tachycardia, and 1 developed multiple ventricular extrasystoles. All 3 arrhythmias occurred during early recovery after exercise testing and resolved spontaneously. Makimoto et al. showed that ST-segment augmentation at early recovery was specific in BrS patients, and was significantly associated with a higher cardiac event rate, notably for patients with previous episode of syncope or for asymptomatic patients.[46] On the contrary, Amin et al. failed to show significant differences in the ECG variables and their changes during exercise between symptomatic (prior syncope) and asymptomatic (no prior syncope) BrS patients.[47]

An infero-lateral early repolarization pattern has been shown to be predictive of arrhythmic events.[47,49] Tokioka et al. have recently shown that the combination of QRS-fragmentation and early repolarization pattern enables the identification of high risk patients.[23] In a previous study, including 290 individuals with BrS, an early repolarization pattern manifested as notched or slurred J-point elevation mainly in lateral leads was observed in 35 subjects (12%). However, in this study, the presence of early repolarization pattern was not associated with arrhythmic events during follow-up.[50] Finally, the aVR sign, defined as R wave ≥0.3 mV or R/q ≥0.75 in lead aVR, has been associated arrhythmic events during follow-up.[51]

Electrophysiological Markers

Conflicting evidence exists on the prognostic value of electrophysiological study (EPS) in asymptomatic BS subjects. Previous studies have demonstrated an excellent negative predictive value of EPS.[17,52] On the contrary, in the PRELUDE registry, a negative EPS was not associated with a low risk of an arrhythmic event.[11] Disagreement also exists regarding the positive predictive value of EPS. Data from the Brugada’s series have shown that VT/VF inducibility is predictive for future events.[14,52,53] However, data from other studies do not support the use of EPS in risk stratification.[10,12,18,19]

Important data on the prognostic significance of EPS in BrS are coming from Pedro Brugada’s group.[29] In their series, patients with VF inducibility presented a hazard ratio for events of 8.3. Event free survival for the non-inducible group was 99.0% at 1 year and 96.8% at 5, 10 and 15 years. Among the inducible patients it was 89.0% at 1 year, 78.4% at 5 years and 75.0% at 10 and 15 years. Among asymptomatic patients, those without EPS inducibility had an event free survival of 100.0% at 1 year, and 99.2% at 5, 10 and 15 years. Inducible subject’s event free survival was 90.6% at 1 year and 79.5% at 5, 10 and 15 years. EPS inducibility was also significant for the asymptomatic subjects. Sensitivity of EPS for predicting arrhythmic events was 64.0% and specificity was 86.6%. Positive predictive value was 21.6% and negative predictive value 97.7%. If restricted to asymptomatic patients, these values increased to a sensitivity of 75.0% and a specificity of 91.3% and predictive values to 18.2% and 98.3% respectively.

Based on recent meta-analyses, EPS inducibility appears to have a prognostic role in risk stratification of BrS. Faucher et al. performed a meta-analysis of 13 studies evaluating the prognostic role of EPS in BrS patients according to clinical presentation.[21] In the whole population of BrS patients, VF inducibility was associated with a non significant higher risk of arrhythmic events during follow-up. However, induction of sustained ventricular arrhythmia was significantly and homogeneously associated with an increased risk of arrhythmic events during follow-up in patients with syncope (odds ratio of 3.30). Similarly, the asymptomatic patients with inducible VF had an increased risk of arrhythmic events during follow-up (odds ratio of 4.62) with homogeneous results across the different studies. In Sroubek’s et al. meta-analysis, VF induction was associated with cardiac events during follow-up with a hazard ratio of 2.66, with the greatest risk observed among those induced with single or double extrastimuli.[54] We have recently conducted a meta-analysis of 12 studies comprising 1,104 asymptomatic subjects with BrS who underwent EPS. During follow-up, arrhythmic events occurred in 3.3% of cases. Inducible ventricular arrhythmias at EPS were predictive of future arrhythmic events with an odds ratio of 3.5.[32]

VF inducibility by programmed electrical stimulation, abnormal restitution properties, and ventricular effective refractory period <200 ms.[11] Finally, EPS may establish the presence of sinus node dysfunction, clarify the cause of syncope or treat supraventricular arrhythmias that can mislead the diagnosis or eventually lead to inappropriate ICD therapies.

Multiparametric Risk Stratification Scores

The relationship of these markers and the usefulness of their combination have not been sufficiently examined. Brugada et al. have shown that patients with a spontaneously abnormal ECG, a previous history of syncope, and inducible sustained ventricular arrhythmias had a probability of 27.2% of suffering arrhythmic events during follow-up.[16] Similarly, Priori et al. have demonstrated that the combined presence of spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern and the history of syncope identifies subjects at risk of cardiac arrest.[24] In the same line, Delise et al. have recently proposed that subjects at highest risk are those with spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern and at least two additional risk factors (syncope, family history of SCD, or positive EPS).[17] Okamura et al. have shown that syncope, spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern, and inducible ventricular arrhythmias at EPS are important risk factors and the combination of these risks well stratify the risk of later arrhythmic events.[55] When dividing patients according to the number of these 3 risk factors present, patients with 2 or 3 risk factors experienced arrhythmic events more frequently than those with 0 or 1 risk factor.[55]

Management Of Patients With Brugada Syndrome

Based on 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of SCD, ICD implantation is recommended in BrS patients with aborted SCD or with documented spontaneous sustained ventricular arrhythmias (Class I, LOE C).[8] ICD implantation should be considered in patients with a spontaneous diagnostic type 1 pattern and history of syncope (Class IIa, LOE C).[8] ICD implantation in BrS patients with inducible VF at EPS receives a weak recommendation in the new 2015 ESC Guidelines (Class IIb, LOE C). However, based on recent long term follow-up data[12,29] as well as on two meta-analyses,[21,32] asymptomatic individuals with spontaneous type 1 ECG and inducible VF at EPS are possibly at high risk. Nevertheless, the decision to implant an ICD in asymptomatic patients should be made weighing the potential individual risk for future arrhythmic events against risk of complications and quality of life.[14] In a recent study, a significant number of young BrS patients experience device-related complications (15.9%).[12] Complications consisted of fracture of the ventricular electrode and lead dislocation, and less commonly device infection and pulse generator migration.[12] In this series, 18.7% of patients suffered inappropriate shocks.[12]

Quinidine may be considered as an alternative therapy in patients who denied ICD as well as for treatment of supraventricular arrhythmias.[6,56,57] Low doses of quinidine are effective to prevent the recurrence of VF, including arrhythmic storm, in subjects with BrS with an ICD.[58] Furthermore, quinidine effectively prevents VT/VF induction in patients with BrS at EPS.[56,57] Belhassen et al. have recently reported the long-term outcomes of BrS patients with initially inducible VF at EPS who received quinidine (n=54), disopyramide (n=2) or both (n=4) and underwent a second EPS procedure. Fifty four patients (90%) were responders to ≥ 1 anti-arrhythmic drugs and became non-inducible. No arrhythmic events occurred during class 1A anti-arrhythmic drugs therapy in any of EPS-drug responders and in patients with no baseline inducible VF during a very long follow-up period of 113.3±71.5 months.[59]

Isoprenaline infusion is effective in the management of repeated ICD shocks and arrhythmic storms.[60] Cilostazol and milrinone that boost calcium channel current and quinidine, bepridil and the Chinese herb extract Wenxin Keli that inhibit the transient outward current may be used to suppress the triggers for VF in BrS.[6] Nademanee et al. initially showed that catheter ablation of fractionated electrograms in the epicardial right ventricular outflow rendered VF non-inducible and normalization of the BrS ECG pattern.[61] Long-term outcomes were excellent, with no recurrent VF in all patients off medication. Similarly, in a recent study, following catheter ablation and elimination of the functional substrate in right ventricular outflow tract, all patients became non-inducible during programmed electrical stimulation using up to 3 extrastimuli, while repeated flecainide infusion failed to unmask the diagnostic BrS ECG pattern.8 Although these findings have to be confirmed in future studies, they provide new important information regarding the therapeutic management of BrS patients.

Conclusions

Risk stratification of BrS patients represents a great challenge for the treating physician. Despite the lack of evidence, it is of major importance to make the best risk stratification using every available tool/modality that has been shown to display any prognostic significance. The diagnostic yield may be therefore increased if we use the current tools properly. Although single risk factors display limited prognostic value, multiparametric scores appear to improve risk stratification.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992 Nov 15;20 (6):1391–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martini B, Nava A, Thiene G, Buja G F, Canciani B, Scognamiglio R, Daliento L, Dalla Volta S. Ventricular fibrillation without apparent heart disease: description of six cases. Am. Heart J. 1989 Dec;118 (6):1203–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antzelevitch Charles, Brugada Pedro, Borggrefe Martin, Brugada Josep, Brugada Ramon, Corrado Domenico, Gussak Ihor, LeMarec Herve, Nademanee Koonlawee, Perez Riera Andres Ricardo, Shimizu Wataru, Schulze-Bahr Eric, Tan Hanno, Wilde Arthur. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005 Feb 8;111 (5):659–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152479.54298.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antzelevitch Charles, Patocskai Bence. Brugada Syndrome: Clinical, Genetic, Molecular, Cellular, and Ionic Aspects. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2016 Jan;41 (1):7–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizusawa Yuka, Wilde Arthur A M. Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012 Jun 1;5 (3):606–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nademanee Koonlawee, Raju Hariharan, de Noronha Sofia V, Papadakis Michael, Robinson Laurence, Rothery Stephen, Makita Naomasa, Kowase Shinya, Boonmee Nakorn, Vitayakritsirikul Vorapot, Ratanarapee Samrerng, Sharma Sanjay, van der Wal Allard C, Christiansen Michael, Tan Hanno L, Wilde Arthur A, Nogami Akihiko, Sheppard Mary N, Veerakul Gumpanart, Behr Elijah R. Fibrosis, Connexin-43, and Conduction Abnormalities in the Brugada Syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015 Nov 3;66 (18):1976–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brugada Josep, Pappone Carlo, Berruezo Antonio, Vicedomini Gabriele, Manguso Francesco, Ciconte Giuseppe, Giannelli Luigi, Santinelli Vincenzo. Brugada Syndrome Phenotype Elimination by Epicardial Substrate Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015 Dec;8 (6):1373–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Priori Silvia G, Blomström-Lundqvist Carina, Mazzanti Andrea, Blom Nico, Borggrefe Martin, Camm John, Elliott Perry Mark, Fitzsimons Donna, Hatala Robert, Hindricks Gerhard, Kirchhof Paulus, Kjeldsen Keld, Kuck Karl-Heinz, Hernandez-Madrid Antonio, Nikolaou Nikolaos, Norekvål Tone M, Spaulding Christian, Van Veldhuisen Dirk J. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur. Heart J. 2015 Nov 1;36 (41):2793–867. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raju Hariharan, Papadakis Michael, Govindan Malini, Bastiaenen Rachel, Chandra Navin, O'Sullivan Ann, Baines Georgina, Sharma Sanjay, Behr Elijah R. Low prevalence of risk markers in cases of sudden death due to Brugada syndrome relevance to risk stratification in Brugada syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011 Jun 7;57 (23):2340–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli P G, Gaita F, Tan H L, Babuty D, Sacher F, Giustetto C, Schulze-Bahr E, Borggrefe M, Haissaguerre M, Mabo P, Le Marec H, Wolpert C, Wilde A A M. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010 Feb 9;121 (5):635–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priori Silvia G, Gasparini Maurizio, Napolitano Carlo, Della Bella Paolo, Ottonelli Andrea Ghidini, Sassone Biagio, Giordano Umberto, Pappone Carlo, Mascioli Giosuè, Rossetti Guido, De Nardis Roberto, Colombo Mario. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: results of the PRELUDE (PRogrammed ELectrical stimUlation preDictive valuE) registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012 Jan 3;59 (1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conte Giulio, Sieira Juan, Ciconte Giuseppe, de Asmundis Carlo, Chierchia Gian-Battista, Baltogiannis Giannis, Di Giovanni Giacomo, La Meir Mark, Wellens Francis, Czapla Jens, Wauters Kristel, Levinstein Moises, Saitoh Yukio, Irfan Ghazala, Julià Justo, Pappaert Gudrun, Brugada Pedro. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome: a 20-year single-center experience. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015 Mar 10;65 (9):879–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viskin Sami, Rogowski Ori. Asymptomatic Brugada syndrome: a cardiac ticking time-bomb? Europace. 2007 Sep;9 (9):707–10. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brugada Josep, Brugada Ramon, Antzelevitch Charles, Towbin Jeffrey, Nademanee Koonlawee, Brugada Pedro. Long-term follow-up of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation. 2002 Jan 1;105 (1):73–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamakura Shiro, Ohe Tohru, Nakazawa Kiyoshi, Aizawa Yoshifusa, Shimizu Akihiko, Horie Minoru, Ogawa Satoshi, Okumura Ken, Tsuchihashi Kazufumi, Sugi Kaoru, Makita Naomasa, Hagiwara Nobuhisa, Inoue Hiroshi, Atarashi Hirotsugu, Aihara Naohiko, Shimizu Wataru, Kurita Takashi, Suyama Kazuhiro, Noda Takashi, Satomi Kazuhiro, Okamura Hideo, Tomoike Hitonobu. Long-term prognosis of probands with Brugada-pattern ST-elevation in leads V1-V3. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Oct;2 (5):495–503. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.816892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugada Josep, Brugada Ramon, Brugada Pedro. Determinants of sudden cardiac death in individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome and no previous cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003 Dec 23;108 (25):3092–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000104568.13957.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delise Pietro, Allocca Giuseppe, Marras Elena, Giustetto Carla, Gaita Fiorenzo, Sciarra Luigi, Calo Leonardo, Proclemer Alessandro, Marziali Marta, Rebellato Luca, Berton Giuseppe, Coro Leonardo, Sitta Nadir. Risk stratification in individuals with the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern without previous cardiac arrest: usefulness of a combined clinical and electrophysiologic approach. Eur. Heart J. 2011 Jan;32 (2):169–76. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giustetto Carla, Drago Stefano, Demarchi Pier Giuseppe, Dalmasso Paola, Bianchi Francesca, Masi Andrea Sibona, Carvalho Paula, Occhetta Eraldo, Rossetti Guido, Riccardi Riccardo, Bertona Roberta, Gaita Fiorenzo. Risk stratification of the patients with Brugada type electrocardiogram: a community-based prospective study. Europace. 2009 Apr;11 (4):507–13. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckardt Lars, Probst Vincent, Smits Jeroen P P, Bahr Eric Schulze, Wolpert Christian, Schimpf Rainer, Wichter Thomas, Boisseau Pierre, Heinecke Achim, Breithardt Günter, Borggrefe Martin, LeMarec Herve, Böcker Dirk, Wilde Arthur A M. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005 Jan 25;111 (3):257–63. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153267.21278.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehi Anil K, Duong Truong D, Metz Louise D, Gomes J Anthony, Mehta Davendra. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2006 Jun;17 (6):577–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fauchier Laurent, Isorni Marc Antoine, Clementy Nicolas, Pierre Bertrand, Simeon Edouard, Babuty Dominique. Prognostic value of programmed ventricular stimulation in Brugada syndrome according to clinical presentation: an updated meta-analysis of worldwide published data. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013 Oct 3;168 (3):3027–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.04.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacher Frédéric, Probst Vincent, Maury Philippe, Babuty Dominique, Mansourati Jacques, Komatsu Yuki, Marquie Christelle, Rosa Antonio, Diallo Abou, Cassagneau Romain, Loizeau Claire, Martins Raphael, Field Michael E, Derval Nicolas, Miyazaki Shinsuke, Denis Arnaud, Nogami Akihiko, Ritter Philippe, Gourraud Jean-Baptiste, Ploux Sylvain, Rollin Anne, Zemmoura Adlane, Lamaison Dominique, Bordachar Pierre, Pierre Bertrand, Jaïs Pierre, Pasquié Jean-Luc, Hocini Mélèze, Legal François, Defaye Pascal, Boveda Serge, Iesaka Yoshito, Mabo Philippe, Haïssaguerre Michel. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation. 2013 Oct 15;128 (16):1739–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tokioka Koji, Kusano Kengo F, Morita Hiroshi, Miura Daiji, Nishii Nobuhiro, Nagase Satoshi, Nakamura Kazufumi, Kohno Kunihisa, Ito Hiroshi, Ohe Tohru. Electrocardiographic parameters and fatal arrhythmic events in patients with Brugada syndrome: combination of depolarization and repolarization abnormalities. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 May 27;63 (20):2131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priori Silvia G, Napolitano Carlo, Gasparini Maurizio, Pappone Carlo, Della Bella Paolo, Giordano Umberto, Bloise Raffaella, Giustetto Carla, De Nardis Roberto, Grillo Massimiliano, Ronchetti Elena, Faggiano Giovanna, Nastoli Janni. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation. 2002 Mar 19;105 (11):1342–7. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Letsas Konstantinos P, Efremidis Michalis, Gavrielatos Gerasimos, Filippatos Gerasimos S, Sideris Antonios, Kardaras Fotios. Neurally mediated susceptibility in individuals with Brugada-type ECG pattern. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008 Apr;31 (4):418–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkozy Andrea, Boussy Tim, Kourgiannides Georgios, Chierchia Gian-Battista, Richter Sergio, De Potter Tom, Geelen Peter, Wellens Francis, Spreeuwenberg Marieke Dingena, Brugada Pedro. Long-term follow-up of primary prophylactic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 2007 Feb;28 (3):334–44. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Letsas Konstantinos P, Weber Reinhold, Astheimer Klaus, Mihas Constantinos C, Stockinger Jochem, Blum Thomas, Kalusche Dietrich, Arentz Thomas. Predictors of atrial tachyarrhythmias in subjects with type 1 ECG pattern of Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009 Apr;32 (4):500–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusano Kengo F, Taniyama Makiko, Nakamura Kazufumi, Miura Daiji, Banba Kimikazu, Nagase Satoshi, Morita Hiroshi, Nishii Nobuhiro, Watanabe Atsuyuki, Tada Takeshi, Murakami Masato, Miyaji Kohei, Hiramatsu Shigeki, Nakagawa Koji, Tanaka Masamichi, Miura Aya, Kimura Hideo, Fuke Soichiro, Sumita Wakako, Sakuragi Satoru, Urakawa Shigemi, Iwasaki Jun, Ohe Tohru. Atrial fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome relationships of gene mutation, electrophysiology, and clinical backgrounds. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008 Mar 25;51 (12):1169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieira Juan, Conte Giulio, Ciconte Giuseppe, de Asmundis Carlo, Chierchia Gian-Battista, Baltogiannis Giannis, Di Giovanni Giacomo, Saitoh Yukio, Irfan Ghazala, Casado-Arroyo Ruben, Juliá Justo, La Meir Mark, Wellens Francis, Wauters Kristel, Van Malderen Sophie, Pappaert Gudrun, Brugada Pedro. Prognostic value of programmed electrical stimulation in Brugada syndrome: 20 years experience. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015 Aug;8 (4):777–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudic Boris, Schimpf Rainer, Veltmann Christian, Doesch Christina, Tülümen Erol, Schoenberg Stefan O, Borggrefe Martin, Papavassiliu Theano. Brugada syndrome: clinical presentation and genotype-correlation with magnetic resonance imaging parameters. Europace. 2016 Sep;18 (9):1411–9. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Malderen Sophie C H, Kerkhove Dirk, Theuns Dominic A M J, Weytjens Caroline, Droogmans Steven, Tanaka Kaoru, Daneels Dorien, Van Dooren Sonia, Meuwissen Marije, Bonduelle Maryse, Brugada Pedro, Van Camp Guy. Prolonged right ventricular ejection delay identifies high risk patients and gender differences in Brugada syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015 Jul 15;191:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Letsas Konstantinos P, Liu Tong, Shao Qingmiao, Korantzopoulos Panagiotis, Giannopoulos Georgios, Vlachos Konstantinos, Georgopoulos Stamatis, Trikas Athanasios, Efremidis Michael, Deftereos Spyridon, Sideris Antonios. Meta-Analysis on Risk Stratification of Asymptomatic Individuals With the Brugada Phenotype. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015 Jul 1;116 (1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerrato Natascia, Giustetto Carla, Gribaudo Elena, Richiardi Elena, Barbonaglia Lorella, Scrocco Chiara, Zema Domenica, Gaita Fiorenzo. Prevalence of type 1 brugada electrocardiographic pattern evaluated by twelve-lead twenty-four-hour holter monitoring. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015 Jan 1;115 (1):52–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morita Hiroshi, Kusano Kengo F, Miura Daiji, Nagase Satoshi, Nakamura Kazufumi, Morita Shiho T, Ohe Tohru, Zipes Douglas P, Wu Jiashin. Fragmented QRS as a marker of conduction abnormality and a predictor of prognosis of Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2008 Oct 21;118 (17):1697–704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.770917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Zhengrong, Patel Chinmay, Li Weihua, Xie Qiang, Wu Rong, Zhang Lijuan, Tang Rong, Wan Xiaoquen, Ma Yuxiao, Zhen Wuyang, Gao Lei, Yan Gan-Xin. Role of signal-averaged electrocardiograms in arrhythmic risk stratification of patients with Brugada syndrome: a prospective study. Heart Rhythm. 2009 Aug;6 (8):1156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajiro Youichi, Hagiwara Nobuhisa, Kasanuki Hiroshi. Assessment of markers for identifying patients at risk for life-threatening arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2005 Jan;16 (1):45–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.04313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatsumi Hiroaki, Takagi Masahiko, Nakagawa Eiichiro, Yamashita Hajime, Yoshiyama Minoru. Risk stratification in patients with Brugada syndrome: analysis of daily fluctuations in 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and signal-averaged electrocardiogram (SAECG). J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2006 Jul;17 (7):705–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maury Philippe, Rollin Anne, Sacher Frédéric, Gourraud Jean-Baptiste, Raczka Franck, Pasquié Jean-Luc, Duparc Alexandre, Mondoly Pierre, Cardin Christelle, Delay Marc, Derval Nicolas, Chatel Stéphanie, Bongard Vanina, Sadron Marie, Denis Arnaud, Davy Jean-Marc, Hocini Mélèze, Jaïs Pierre, Jesel Laurence, Haïssaguerre Michel, Probst Vincent. Prevalence and prognostic role of various conduction disturbances in patients with the Brugada syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013 Nov 1;112 (9):1384–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Junttila M Juhani, Brugada Pedro, Hong Kui, Lizotte Eric, DE Zutter Marc, Sarkozy Andrea, Brugada Josep, Benito Begona, Perkiomaki Juha S, Mäkikallio Timo H, Huikuri Heikki V, Brugada Ramon. Differences in 12-lead electrocardiogram between symptomatic and asymptomatic Brugada syndrome patients. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2008 Apr;19 (4):380–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takagi Masahiko, Yokoyama Yasuhiro, Aonuma Kazutaka, Aihara Naohiko, Hiraoka Masayasu. Clinical characteristics and risk stratification in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with brugada syndrome: multicenter study in Japan. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2007 Dec;18 (12):1244–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro Hevia Jesus, Antzelevitch Charles, Tornés Bárzaga Francisco, Dorantes Sánchez Margarita, Dorticós Balea Francisco, Zayas Molina Roberto, Quiñones Pérez Miguel A, Fayad Rodríguez Yanela. Tpeak-Tend and Tpeak-Tend dispersion as risk factors for ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation in patients with the Brugada syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006 May 2;47 (9):1828–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Letsas Konstantinos P, Weber Reinhold, Astheimer Klaus, Kalusche Dietrich, Arentz Thomas. Tpeak-Tend interval and Tpeak-Tend/QT ratio as markers of ventricular tachycardia inducibility in subjects with Brugada ECG phenotype. Europace. 2010 Feb;12 (2):271–4. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyamoto Akashi, Hayashi Hideki, Makiyama Takeru, Yoshino Tomohide, Mizusawa Yuka, Sugimoto Yoshihisa, Ito Makoto, Xue Joel Q, Murakami Yoshitaka, Horie Minoru. Risk determinants in individuals with a spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG. Circ. J. 2011;75 (4):844–51. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tada Takeshi, Kusano Kengo Fukushima, Nagase Satoshi, Banba Kimikazu, Miura Daiji, Nishii Nobuhiro, Watanabe Atsuyuki, Nakamura Kazufumi, Morita Hiroshi, Ohe Tohru. Clinical significance of macroscopic T-wave alternans after sodium channel blocker administration in patients with Brugada syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2008 Jan;19 (1):56–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masrur Shihab, Memon Sarfaraz, Thompson Paul D. Brugada syndrome, exercise, and exercise testing. Clin Cardiol. 2015 May;38 (5):323–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.22386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makimoto Hisaki, Nakagawa Eiichiro, Takaki Hiroshi, Yamada Yuko, Okamura Hideo, Noda Takashi, Satomi Kazuhiro, Suyama Kazuhiro, Aihara Naohiko, Kurita Takashi, Kamakura Shiro, Shimizu Wataru. Augmented ST-segment elevation during recovery from exercise predicts cardiac events in patients with Brugada syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010 Nov 2;56 (19):1576–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amin Ahmad S, de Groot Elisabeth A A, Ruijter Jan M, Wilde Arthur A M, Tan Hanno L. Exercise-induced ECG changes in Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Oct;2 (5):531–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.862441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawata Hiro, Morita Hiroshi, Yamada Yuko, Noda Takashi, Satomi Kazuhiro, Aiba Takeshi, Isobe Mitsuaki, Nagase Satoshi, Nakamura Kazufumi, Fukushima Kusano Kengo, Ito Hiroshi, Kamakura Shiro, Shimizu Wataru. Prognostic significance of early repolarization in inferolateral leads in Brugada patients with documented ventricular fibrillation: a novel risk factor for Brugada syndrome with ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Aug;10 (8):1161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarkozy Andrea, Chierchia Gian-Battista, Paparella Gaetano, Boussy Tim, De Asmundis Carlo, Roos Marcus, Henkens Stefan, Kaufman Leonard, Buyl Ronald, Brugada Ramon, Brugada Josep, Brugada Pedro. Inferior and lateral electrocardiographic repolarization abnormalities in Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Apr;2 (2):154–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.795153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Letsas Konstantinos P, Sacher Frédéric, Probst Vincent, Weber Reinhold, Knecht Sébastien, Kalusche Dietrich, Haïssaguerre Michel, Arentz Thomas. Prevalence of early repolarization pattern in inferolateral leads in patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008 Dec;5 (12):1685–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Babai Bigi Mohamad Ali, Aslani Amir, Shahrzad Shahab. aVR sign as a risk factor for life-threatening arrhythmic events in patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2007 Aug;4 (8):1009–12. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brugada Pedro, Brugada Ramon, Mont Lluis, Rivero Maximo, Geelen Peter, Brugada Josep. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: the prognostic value of programmed electrical stimulation of the heart. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2003 May;14 (5):455–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brugada Pedro, Brugada Ramon, Brugada Josep. Should patients with an asymptomatic Brugada electrocardiogram undergo pharmacological and electrophysiological testing? Circulation. 2005 Jul 12;112 (2):279–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.485326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sroubek Jakub, Probst Vincent, Mazzanti Andrea, Delise Pietro, Hevia Jesus Castro, Ohkubo Kimie, Zorzi Alessandro, Champagne Jean, Kostopoulou Anna, Yin Xiaoyan, Napolitano Carlo, Milan David J, Wilde Arthur, Sacher Frederic, Borggrefe Martin, Ellinor Patrick T, Theodorakis George, Nault Isabelle, Corrado Domenico, Watanabe Ichiro, Antzelevitch Charles, Allocca Giuseppe, Priori Silvia G, Lubitz Steven A. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation for Risk Stratification in the Brugada Syndrome: A Pooled Analysis. Circulation. 2016 Feb 16;133 (7):622–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okamura Hideo, Kamakura Tsukasa, Morita Hiroshi, Tokioka Koji, Nakajima Ikutaro, Wada Mitsuru, Ishibashi Kohei, Miyamoto Koji, Noda Takashi, Aiba Takeshi, Nishii Nobuhiro, Nagase Satoshi, Shimizu Wataru, Yasuda Satoshi, Ogawa Hisao, Kamakura Shiro, Ito Hiroshi, Ohe Tohru, Kusano Kengo F. Risk stratification in patients with Brugada syndrome without previous cardiac arrest – prognostic value of combined risk factors. Circ. J. 2015;79 (2):310–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hermida Jean-Sylvain, Denjoy Isabelle, Clerc Jérôme, Extramiana Fabrice, Jarry Geneviève, Milliez Paul, Guicheney Pascale, Di Fusco Stefania, Rey Jean-Luc, Cauchemez Bruno, Leenhardt Antoine. Hydroquinidine therapy in Brugada syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004 May 19;43 (10):1853–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belhassen Bernard, Glick Aharon, Viskin Sami. Efficacy of quinidine in high-risk patients with Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2004 Sep 28;110 (13):1731–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143159.30585.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Márquez Manlio F, Bonny Aimé, Hernández-Castillo Eduardo, De Sisti Antonio, Gómez-Flores Jorge, Nava Santiago, Hidden-Lucet Françoise, Iturralde Pedro, Cárdenas Manuel, Tonet Joelci. Long-term efficacy of low doses of quinidine on malignant arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: a case series and literature review. Heart Rhythm. 2012 Dec;9 (12):1995–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belhassen Bernard, Rahkovich Michael, Michowitz Yoav, Glick Aharon, Viskin Sami. Management of Brugada Syndrome: Thirty-Three-Year Experience Using Electrophysiologically Guided Therapy With Class 1A Antiarrhythmic Drugs. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015 Dec;8 (6):1393–402. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohgo Takeshi, Okamura Hideo, Noda Takashi, Satomi Kazuhiro, Suyama Kazuhiro, Kurita Takashi, Aihara Naohiko, Kamakura Shiro, Ohe Tohru, Shimizu Wataru. Acute and chronic management in patients with Brugada syndrome associated with electrical storm of ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007 Jun;4 (6):695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nademanee Koonlawee, Veerakul Gumpanart, Chandanamattha Pakorn, Chaothawee Lertlak, Ariyachaipanich Aekarach, Jirasirirojanakorn Kriengkrai, Likittanasombat Khanchit, Bhuripanyo Kiertijai, Ngarmukos Tachapong. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation episodes in Brugada syndrome by catheter ablation over the anterior right ventricular outflow tract epicardium. Circulation. 2011 Mar 29;123 (12):1270–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]