Four jasmonate conjugates are perceived by receptor COI1 and function as new endogenous bioactive JA molecules.

Abstract

Jasmonates (JAs) regulate a wide range of plant defense and development processes. The bioactive JA is perceived by its receptor COI1 to trigger the degradation of JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) proteins and subsequently derepress the JAZ-repressed transcription factors for activation of expression of JA-responsive genes. So far, (+)-7-iso-JA-l-Ile has been the only identified endogenous bioactive JA molecule. Here, we designed coronafacic acid (CFA) conjugates with all the amino acids (CFA-AA) to mimic the JA amino acid conjugates, and revealed that (+)-7-iso-JA-Leu, (+)-7-iso-JA-Val, (+)-7-iso-JA-Met, and (+)-7-iso-JA-Ala are new endogenous bioactive JA molecules. Furthermore, our studies uncover the general characteristics for all the bioactive JA molecules, and provide a new strategy to synthetically generate novel active JA molecules.

Hormones are chemicals produced in vivo that regulate the growth and developmental processes in trace amounts (Fonseca et al., 2014). Each hormone often consists of multiple chemicals with similar structure and biosynthetic origin in planta (Xuan et al., 2013). These multiple chemicals would be generally converted to the active hormone molecules, which specifically bind their receptors to trigger hormone signal transduction in vivo. Screening and identification of endogenous active hormone are essential for elucidation of hormone perception mechanisms (Xuan et al., 2013; Fonseca et al., 2014). In the past few decades, many active forms of plant hormones have been identified, including indole-3-acetic acid for auxin (Tan et al., 2007; Normanly, 2010), gibberellic acid 1/3/4 for gibberellin (Shimada et al., 2008; Hedden and Thomas, 2012), (+)-abscisic acid (cis-ABA) for abscisic acid (Melcher et al., 2009; Miyazono et al., 2009; Nishimura et al., 2009; Santiago et al., 2009), and transzeatin and isopentenyladenine for cytokinin (Inoue et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001; Pasternak et al., 2006).

Jasmonates (JAs), a class of cyclic fatty acid-derived phytohormones (Vick and Zimmerman, 1984), regulate various developmental processes as well as diverse defense responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Santino et al., 2013; Wang and Wu, 2013; Campos et al., 2014; Wasternack, 2014). In jasmonate biosynthetic pathway, the linolenic acid is catalyzed and converted into jasmonic acid through sequential actions of various biosynthesis enzymes, including lipoxygenase (LOX), allene oxide synthase (AOS), allene oxide cyclase, and oxophytodienoate reductase 3 (OPR3; Wasternack and Hause, 2013). Jasmonic acid can be further enzymatically modified into different derivatives such as methyl jasmonate, cis-jasmone, jasmonoyl ACC, and the conjugate with amino acid Ile (JA-Ile; Wasternack and Hause, 2013).

The jasmonic acid molecule contains two chiral centers located at C3 and C7 of cyclopentanone ring (Creelman and Mullet, 1997), which generates four different stereoisomers. Among these four stereoisomers of JA-Ile, only one stereoisomer, (+)-7-iso-JA-l-Ile ((+)-7-iso-JA-Ile), acts as endogenous bioactive JA molecule (Fonseca et al., 2009), which binds to receptor COI1 and triggers jasmonate signaling. Previous studies have shown that the relative orientation of the C3 and C7 bonds (3R and 7S confirmation) is essential for JA bioactivity. However, the 3R and 7S conformation in JA moiety is mutable and susceptible to heat or solution PH value (Fonseca et al., 2009), which has been seriously hampering the discovery of novel JA active molecules.

In present study, we developed a new strategy to identify novel JA bioactive forms and revealed that, in addition to (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile (Fonseca et al., 2009), four JA-amino acid conjugates, (+)-7-iso-JA-Ala, (+)-7-iso-JA-Val, (+)-7-iso-JA-Leu, and (+)-7-iso-JA-Met, function as endogenous JA bioactive molecules. Moreover, we showed that different COI1 homologs perceive these bioactive JA amino acid conjugates with obviously different preferences. Finally, we revealed general features for all the JA bioactive molecules, which would serve as guidelines to design novel synthetic active JA molecules.

RESULTS

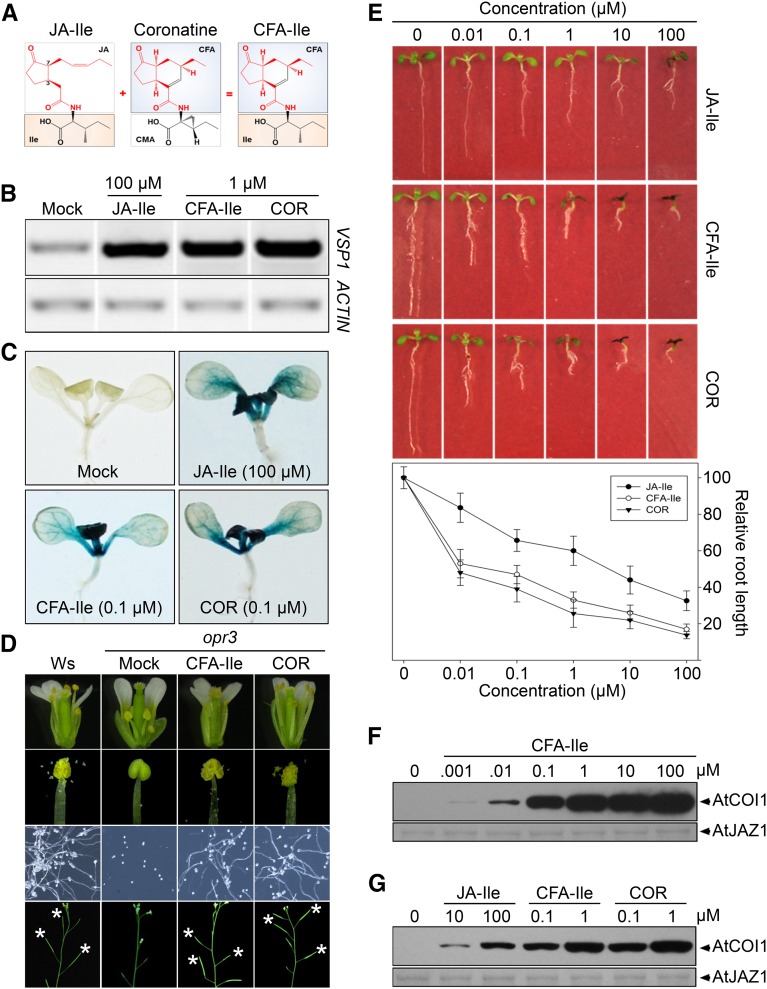

CFA-Ile Fully Mimics (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile

As the stereostructure of coronafacic acid (CFA) moiety of coronatine (COR) is quite stable (Fonseca et al., 2009) and identical to that in cyclopentanone ring of (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile (Fig. 1A), we synthesized the CFA isoLeu conjugate (CFA-Ile; Fig. 1A). Given that COR mimics (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile in bioactivity as well as molecular mechanism of action (Fonseca et al., 2009), we compared the activity of CFA-Ile with COR to elucidate the relationship between CFA-Ile and (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile. As shown in Figure 1B, the real-time PCR analysis showed that CFA-Ile and COR had a similar effect on inducing the expression of VSP1 (a JA-responsive marker gene) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seedlings, suggesting that the bioactivity of CFA-Ile is analogous to that of COR. Consistent with the observation from the real-time PCR analysis, CFA-Ile showed the same activity with COR on inducing GUS expression of transgenic seedlings with GUS reporter gene driven by AtVSP1 promoter (AtVSP1::GUS; Fig. 1C; Supplemental Fig. S1A). Furthermore, CFA-Ile and COR similarly restored the fertility of opr3 but not coi1-1 plants (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Fig. S2, A and B) and inhibited the root length of Col-0 seedlings (Fig. 1E; Supplemental Fig. S2C), demonstrating that CFA-Ile performs the almost identical bioactivity as COR in JA physiological responses in Arabidopsis.

Figure 1.

CFA-Ile exhibits the similar bioactivity and perception mechanism with COR. A, Chemical structure of (+)-7-iso-JA-l-Ile, COR, and CFA-Ile. CFA-Ile is constructed by the head part (red) of COR and the tail part (black) of (+)-7-iso-JA-l-Ile. B, VSP1 expression level in 7-d-old Col-0 seedlings treated with solvent (Mock), 100 µm JA-Ile, 1 µM CFA-Ile, or 1 µm COR, respectively, for 8 h. C, GUS staining of 7-d-old seedlings of AtVSP1::GUS transgenic plants treated with solvent (Mock), 100 μm JA-Ile, 0.1 μm CFA-Ile, or 0.1 μm COR, respectively, for 8 h. D, Restoration of the fertility of opr3 plants by CFA-Ile and COR. Pictures show the flower (top row), dehisced anther (second row), elongated filaments (third row), and main inflorescence (bottom row) of Ws (Wassilewskija) and opr3-treated with solvent (Mock), 400 µm CFA-Ile, or COR. E, Root length of 7-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown on MS with JA-Ile, CFA-Ile, or COR in different concentrations. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 30). F, CFA-Ile triggers the interaction of COI1 and JAZ1 in a dose-dependent manner. Recombinant JAZ1 and total plant extracts from the coi1-1 transgenic for HA-COI1 were used in the pull-down assay. HA-COI1 was detected with a HA antibody (top), and the input of JAZ1 was shown with Coomassie Blue staining (bottom). G, Activity comparison of JA-Ile, CFA-Ile, and COR on promoting the COI1-JAZ1 interaction in pull-down assay. HA-COI1 was detected with a HA antibody (top), and the input of JAZ1 was showed with Coomassie Blue staining.

Pull-down assays, using the purified MBP-AtJAZ1-his protein and the total protein of transgenic plants expressing HA-tagged COI1, showed that CFA-Ile can promote the interaction of COI1 and JAZ1 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1F; Supplemental Fig. S1B). Further comparison of the activity between CFA-Ile and COR showed that they promoted the COI1-JAZ1 interaction at comparable level (Fig. 1G), demonstrating that CFA-Ile and COR have similar bioactivity and share a common function mechanism.

Previous studies showed that COR exhibits more than 100 times activity compared to a mixture of JA-Ile isomers (JA-Ile; Fonseca et al., 2009; Seo et al., 2011). Consistently, we found that CFA-Ile had more than 100-fold higher activity compared to a mixture of JA-Ile isomers (JA-Ile) on inducing the expression level of VSP1 (Fig. 1, B and C), inhibiting the root length of Col-0 seedlings (Fig. 1E) and promoting the AtCOI1 interaction with AtJAZ1 (Fig. 1G).

Taken together, these results demonstrated that CFA-Ile is able to mimic COR and (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile in bioactivity as well as molecular mechanism of action and suggested that CFA amino acid conjugates can be used for mimicking (+)-7-iso-JA amino acid conjugates.

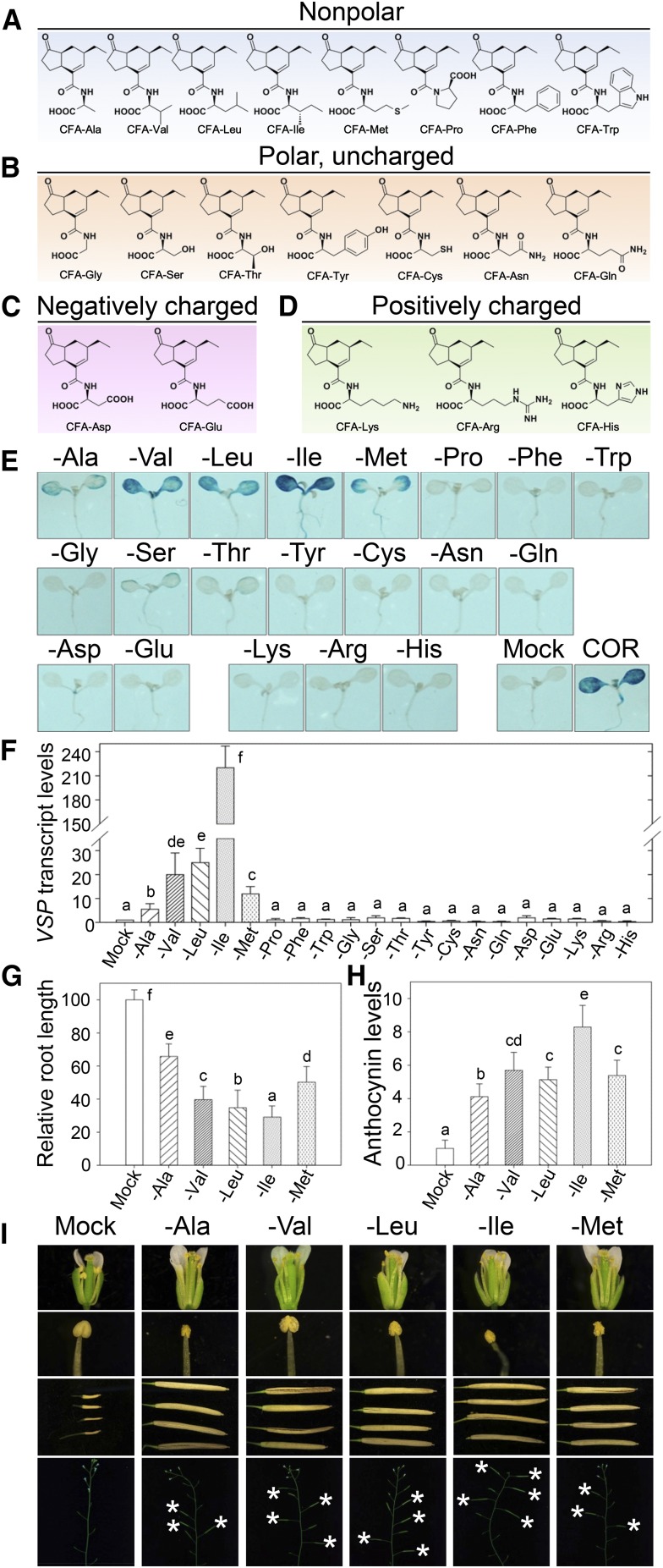

Identification of New Active CFA Amino Acid Conjugates

We respectively coupled twenty different l-amino acids with CFA through amide bonds to form corresponding CFA amino acid conjugates (CFA conjugates; Fig. 2, A–D; Supplemental Fig. S3; Supplemental Table S1). Based on the properties of the “R” group in each amino acid, the CFA conjugates can be classified into four groups, including a nonpolar group (Fig. 2A), a polar and uncharged group (Fig. 2B), a negatively charged group (Fig. 2C), and a positively charged group (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Screening of active CFA amino acid conjugates in Arabidopsis. A to D, Chemical structures and classification of 20 kinds of CFA amino acid conjugates. Different colors represent different groups of these CFA amino acid conjugates: nonpolar CFA amino acid conjugates (A), polar and uncharged CFA amino acid conjugates (B), negatively charged CFA amino acid conjugates (C), and positively charged CFA amino acid conjugates (D). E, GUS staining of 7-d-old seedlings of AtVSP1::GUS transgenic plants treated with solvent (Mock), 10 µm COR, or CFA amino acid conjugates for 8 h, respectively. F, Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of VSP transcription level in 7-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown on MS with solvent (Mock), 10 µm COR, or CFA amino acid conjugates, respectively. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 3). G, Relative root length of 7-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown on MS with solvent (Mock), 10 µm COR or CFA amino acid conjugates. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 30). H, Relative levels of anthocyanin of 7-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown on MS with solvent (Mock), 10 µm COR, or CFA amino acid conjugates, respectively. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean represent ± sd (n = 30). I, Effect of active CFA conjugates on restoring the fertility of opr3 plants. Pictures show the flowers (top row), dehisced anthers (second row), mature siliques (third row), and main inflorescences (bottom row) of opr3 treated with solvent (Mock) and 400 µm CFA conjugates, respectively.

To examine the bioactivity of these synthetic CFA conjugates, 7-d-old AtVSP1::GUS transgenic seedlings were treated with various CFA conjugates for validation of inducible expression of AtVSP1. Histochemical staining showed that five CFA conjugates, CFA-Ile, CFA-Leu, CFA-Val, CFA-Met, and CFA-Ala, significantly activated the AtVSP1 promoter to induce the GUS activity in the seedlings (Fig. 2E). Consistent with the histochemical staining, these five CFA conjugates obviously induced expression of VSP1 gene in quantitative real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 2F).

Furthermore, these five CFA conjugates (CFA-Ile, CFA-Leu, CFA-Val, CFA-Met, and CFA-Ala) were able to inhibit root growth (Fig. 2G), promote anthocyanin accumulation of Col-0 seedlings (Fig. 2H; Supplemental Fig. S1C), restore the fertility of opr3 plants by inducing filament elongation and anther dehiscence (Fig. 2I), and trigger JAZ1 degradation by the 26S proteasome (Supplemental Fig. S4A).

Interestingly, JA activities were detected in these five CFA conjugates that belong to the nonpolar group, but not in other CFA conjugates belonging to the polar, positively charged, or negatively charged groups (Fig. 2, E–H; Supplemental Fig. S5). Our results showed that these CFA conjugates possess typical JA physiological bioactivities, suggesting that, similar to (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile, their corresponding JA conjugates (+)-7-iso-JA-Leu, (+)-7-iso-JA-Val, (+)-7-iso-JA-Met, and (+)-7-iso-JA-Ala might be new endogenous bioactive jasmonates in plant.

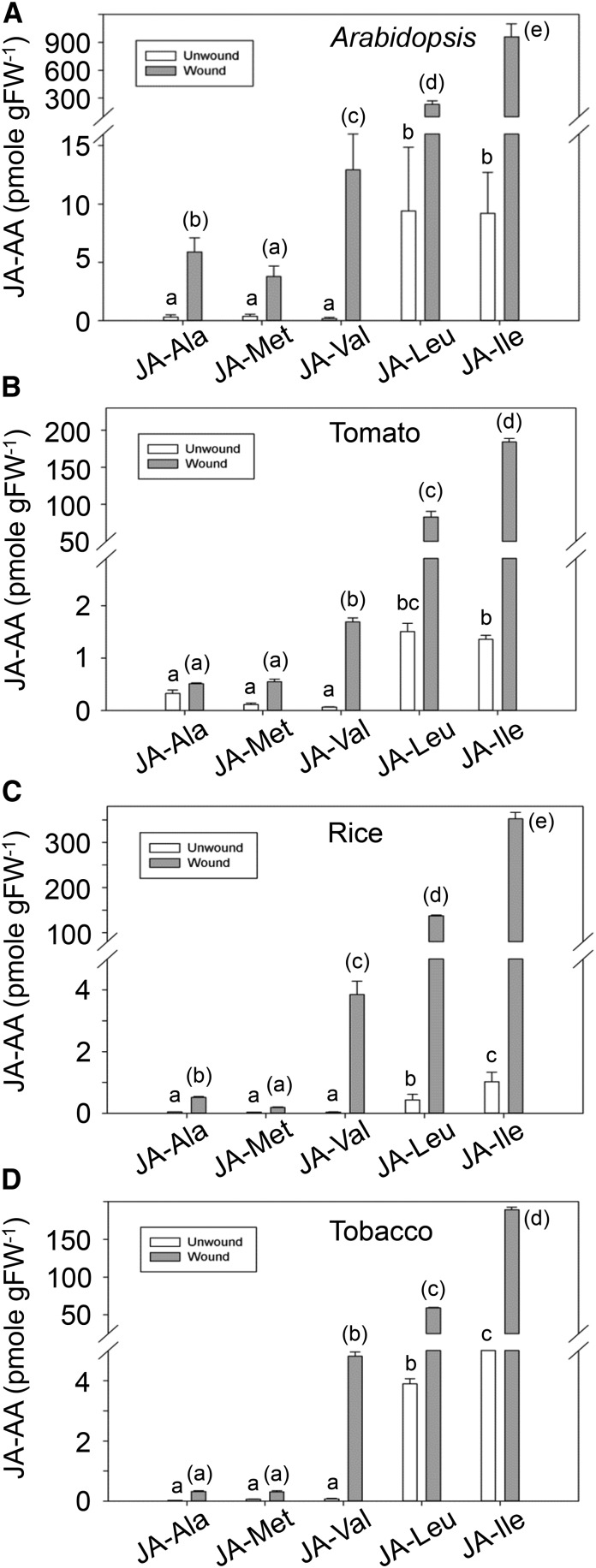

Detection of the Newly Identified JA Active Molecules in Different Plants

To further confirm whether the four JA conjugates (JA-Ala, JA-Val, JA-Leu, JA-Met) actually exist in plant, Arabidopsis rosette leaves were subjected to wounding treatment and collected for measurement of the endogenous JA conjugates. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis showed, in unwounded leaves, all the five JA conjugates (JA-Ala, JA-Val, JA-Leu, JA-Met, and JA-Ile) kept their abundances at low level. However, in the wounded leave, these five JA conjugates (JA-Ala, JA-Val, JA-Leu, JA-Met, and JA-Ile) were all obviously biosynthesized: JA-Ile raised up to ∼900 pmol/g fresh weight (FW), JA-Leu to about 90 pmol/g FW, and JA-Val, JA-Ala, and JA-Met at <15 pmol/g FW level (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Endogenous JA conjugates in different plant species. A to D, Concentration of JA-Ala, JA- Met, JA-Val JA-Leu, and JA-Ile in unwounded and wounded leaves (for 1 h) of different plant species. A, 4-week-old Col-0 plants. B, 45-d-old tomato plants. C, Rice in fourth-leaf stage. D, 45-d-old tobacco plants. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis. Parentheses are added to the lowercase letters for the statistical significant analysis of wound leaves. P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 3).

Similarly, in tomato (Solanum peruvianum), rice (Oryza sativa), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), all of these five JA conjugates were clearly detected in unwounded leaves, though at low levels, and obviously induced by wounding treatment (Fig. 3, B–D). These results showed that similar to JA-Ile, the four new JA conjugates (JA-Ala, JA-Val, JA-Leu, and JA-Met) were detected in various plant species and obviously induced in response of wounding treatment, revealing the existence of these newly identified JA active molecules in plant.

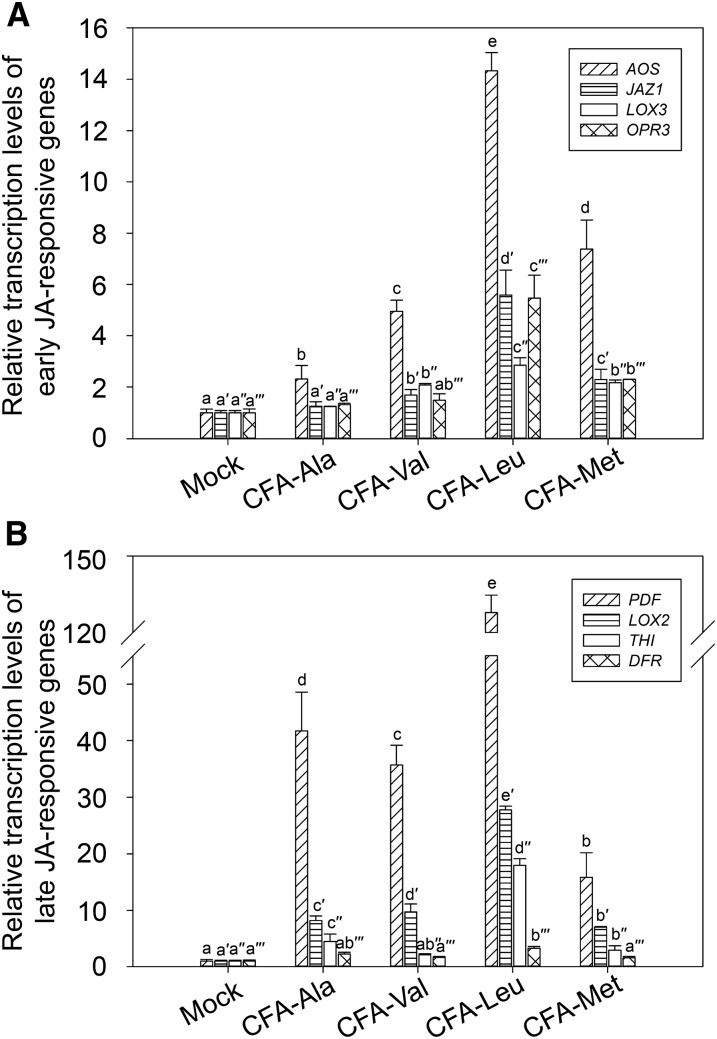

Active CFA Conjugates Exhibited Different Preference on Regulation of JA-Responsive Genes

We further examined inducible expression of JA-responsive genes to investigate the roles of the newly identified CFA amino acid conjugates. As shown in Figure 4, CFA-Leu showed the strongest effect on inducing both early and late JA-responsive genes. Interestingly, CFA-Met exhibited stronger activity than CFA-Ala and CFA-Val on inducing the expression of early JA-responsive genes, especially AOS (Fig. 4A), but it had weaker effect compared to CFA-Ala and CFA-Val on inducing transcript levels of late JA-responsive genes such as PDF1.2 and LOX2 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that CFA-Met may play a more important role in regulating early JA-responsive genes than CFA-Ala and CFA-Val. In contrast, CFA-Ala exhibited relatively strong activity in increasing the late JA-responsive genes, but very weak activity in inducing early JA-responsive genes, indicating that its role may focus on regulating late JA-responsive genes. These results suggest that the newly identified JA active molecules exhibited different preference on regulation of JA-responsive genes,

Figure 4.

Function of CFA conjugates on inducing JA-responsive genes. A, Relative transcription of early JA-responsive genes (AOS, JAZ1, LOX3, and OPR3) of Arabidopsis seedlings treated with 1 μm CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, or CFA-Met, respectively, for 1 h. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis. Superscripts are added to the lowercase letters for the statistical significant analysis of each gene. P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 6). B, Relative transcription of late JA-responsive genes (PDF1.2, LOX2, THI2.1, and DFR) of Arabidopsis seedlings treated with 1 μm CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, or CFA-Met, respectively, for 8 h. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis. Superscripts are added to the lowercase letters for the statistical significant analysis of each gene. P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 6).

The Newly Identified CFA Conjugates Are Perceived by COI1

To reveal action mechanisms of the new active JA conjugates, we first analyzed their physiological effects on inhibiting root growth in Arabidopsis coil mutant. As shown in Figure 5,A and B, the CFA conjugates could not inhibit the root length of coi1-1 mutant compared with that of Col-0 seedlings, which suggested that the CFA conjugates perform their functions in COI1-dependent manner.

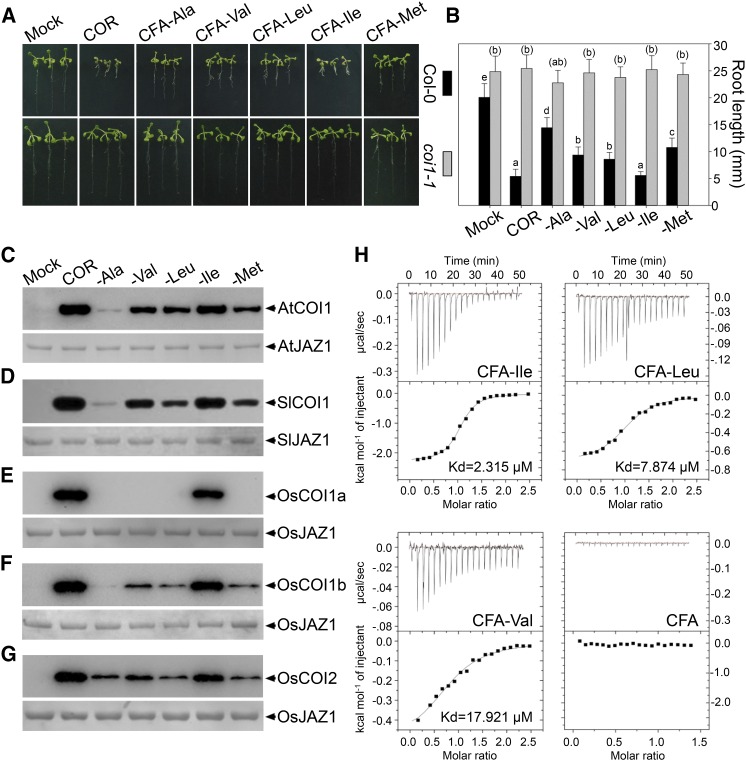

Figure 5.

Molecular mechanism of active CFA conjugates in Arabidopsis. A, Phenotype of 10-d-old Col-0 and coi1-1 mutant seedlings grown on MS with solvent (Mock), 1 µm COR, or CFA conjugates. B, Quantitative analysis of root length of seedlings in A. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis. Parentheses are added to the lowercase letters for the statistical significant analysis of coi1-1. P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 30). C to G, Immunoblot of recovered Flag-COI1 by JAZ1 in pull-down assays in presence of 1 µm COR or CFA conjugates. COI1 was detected with a flag antibody (C–G, top), and the input of JAZ1 was showed with Coomassie Blue staining (C–G, bottom). C, AtCOI1and AtJAZ1. D, SlCOI1 and SlJAZ1. E, OsCOI1a and OsJAZ1. F, OsCOI1b and OsJAZ1. G, OsCOI12 and OsJAZ1. H, ITC results of injecting CFA conjugates into AtCOI1 protein, respectively. Dissociation constant (Kd) of CFA-Ile, CFA-Leu, and CFA-Val are 2.315 µm, 7.874 µm, and 17.921 µm, respectively. As a control, CFA showed no change in heat capacity.

Next, we expressed and purified the COI1 and JAZ proteins from various plant species, including Arabidopsis, tomato, and rice, to examine the role of the JA active molecules in promoting COI1-JAZ interaction. Pull-down assay showed that these JA active molecules all clearly induced the COI1-JAZ interaction in Arabidopsis (AtCOI1 and AtJAZ1) or tomato (SlCOI1 and SlJAZ1; Fig. 5, C and D).

Interestingly, the three rice COI1 paralogs exhibited significant differences on recognition of the four newly identified active CFA conjugates. Pull-down assays showed that CFA-Ile and COR exhibited obvious activity to promote the interaction of OsJAZ1 with all three OsCOI1 paralogs (OsCOI1a, OsCOI1b, OsCOI12; Fig. 5, E–G). However, the interaction between OsCOI1a and OsJAZ1 was not induced by the four new active molecules (CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, or CFA-Met; Fig. 5E), whereas the interaction of OsCOI12 with OsJAZ1 was equally induced at low level by all the four CFA conjugates (Fig. 5G). Surprisingly, interaction of OsCOI1b with OsJAZ1 was induced by CFA-Val, CFA-Met, and CFA-Leu, but not by CFA-Ala (Fig. 5F). These results suggested that different rice COI1 paralogs possess remarkable divergent preference to the active JA conjugates, implying that some subtle structure variations of COI1 proteins can lead to dramatic changes in recognition of JA active conjugates.

We further employed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to examine the physical interaction between COI1 and the CFA conjugate CFA-Ile, CFA-Leu, or CFA-Val. When CFA-Ile, CFA-Leu, or CFA-Val was injected into the AtCOI1 protein, the best fit for the integrated heat data were obtained using one set of sites fitting model, yielding the thermodynamic parameters for the interaction (Fig. 5H). The binding constant (Kd) values were 2.315 ± 0.182 μm for CFA-Ile, 7.874 ± 0.762 μm for CFA-Leu, and 17.921 ± 2.342 μm for CFA-Val, respectively (Fig. 5H; Supplemental Table S2).

Taken together, these results demonstrated that CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, CFA-Ile, and CFA-Met are the endogenous active JA molecules in various plant species, including Arabidopsis, tomato, and rice. Different from the previously identified JA-Ile that exhibits the strongest bioactivity in all detected species, the newly defined four active conjugates showed different preferences on promoting the COI1-JAZ interaction, indicating that these four new JA conjugates are auxiliaries and helpers for a fine tuning of JA signaling.

Basic Features of JA Bioactive Molecules

Previous studies showed that the cis configuration of the C3 and C7 bonds in the JA cyclopentanone ring is essential for bioactivities of JA (Fonseca et al., 2009). By analyzing the fundamental structure specificities of our newly identified active CFA conjugates, we revealed two novel basic criteria for bioactive JA molecules: (1) the amino acid in an active JA conjugate should be nonpolar, and (2) the side chain length of amino acid should be less than five carbons.

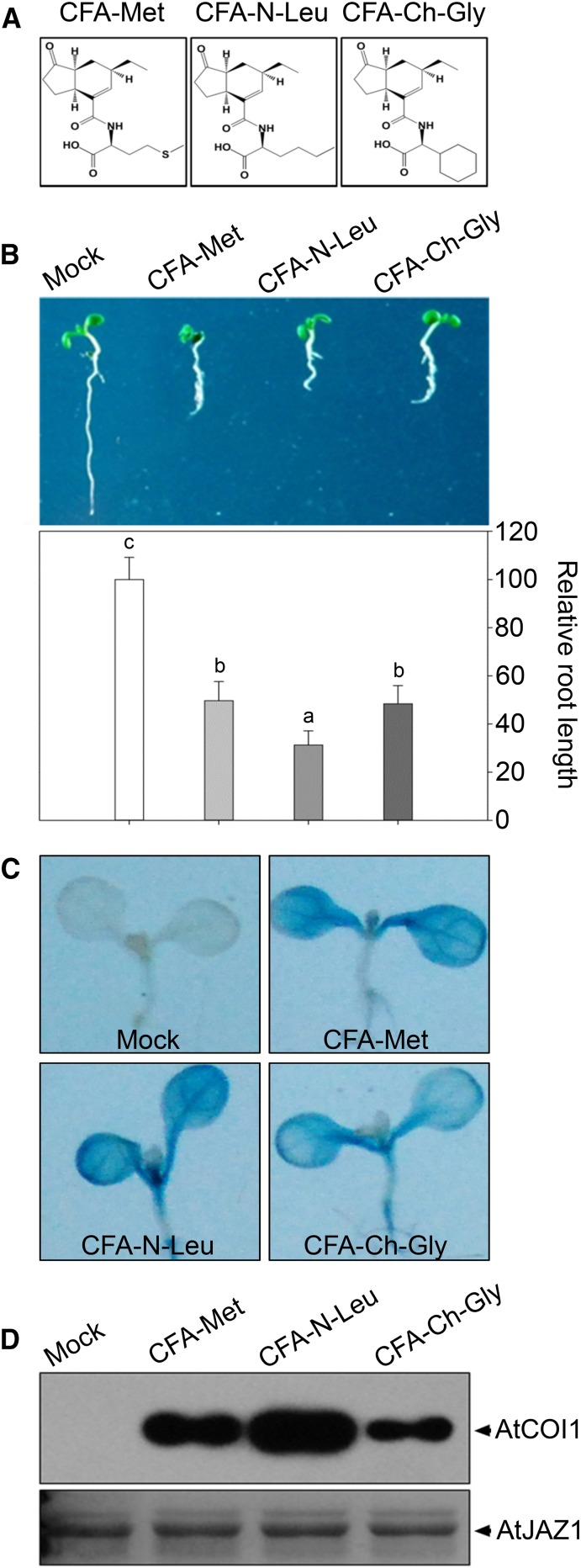

In order to validate these general criteria for active JA molecules, we followed the basic criteria to design and synthesize two new CFA conjugates. We made substitution of the sulfur atom with a carbon atom in Met of CFA-Met to generate the new CFA conjugate, named CFA-Nor-Leu (CFA-N-Leu; Fig. 6A). Based the first criterion, this substitution would result in a higher bioactivity, as hydrophobicity in CFA-N-Leu is increased compared to CFA-Met. Indeed, physiological activity analyses showed that CFA-N-Leu was more active than CFA-Met on inhibiting root length of Col-0 seedlings (Fig. 6B) and on promoting GUS activity in AtVSP1::GUS transgenic seedlings (Fig. 6C). In addition, pull-down assay demonstrated that CFA-N-Leu had stronger effect than CFA-Met on promoting the interaction of COI1 and JAZ1 (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Bioactivities of synthetic JA conjugates CFA-N-Leu and CFA-Ch-Gly. A, Chemical structures of CFA-Met, CFA-N-Leu, and CFA-Ch-Gly. B, Root length of 7-d-old Col-0 seedlings grown on MS with solvent (Mock), 10 µm CFA-Met, CFA-N-Leu, or CFA-Ch-Gly. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significant analysis; P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± sd (n = 30). C, GUS staining of 7-d-old seedlings of AtVSP1::GUS transgenic plants treated with solvent (Mock), 10 µm CFA-Met, CFA-N-Leu, or CFA-Ch-Gly for 8 h, respectively. D, Immunoblot of recovered HA-COI1 from crude protein extracts of 35S::HA-COI1 plants by JAZ1 in pull-down assays in presence of 1 µm CFA-Met, CFA-N-Leu, or CFA-Ch-Gly. HA-COI1 was detected with a HA antibody (top), and the input of was AtJAZ1 showed with Coomassie Blue staining (bottom).

We further designed a new CFA conjugate (referred to as CFA-Ch-Gly) by covalently conjugating CFA with a cyclohexyl-Gly (Fig. 6A). According to the second criteria about the five carbons restriction in side-chain length, the synthetic molecule CFA-Ch-Gly is expected to exhibit JA bioactivity. Consistent with our speculation, CFA-Ch-Gly exhibited obvious JA activities on inhibiting root length and inducing AtVSP1::GUS expression (Fig. 6, B and C). Moreover, CFA-Ch-Gly obviously promoted the interaction of COI1 with JAZ1 in pull-down assays (Fig. 6D) and induced JAZ1 degradation by the 26S proteasome (Supplemental Fig. S4B).

Taken together, these results verified the basic structure requirements for active JA conjugates, and it is feasible to design entirely new active JA conjugates according to the features.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have detected several JA amino acid conjugates other than JA-Ile in Arabidopsis (Staswick and Tiryaki, 2004; Suza and Staswick, 2008; Koo et al., 2009; Staswick, 2009), rice (Wakuta et al., 2011), barley (Hordeum vulgare; Kramell et al., 1995), tomato (Suza et al., 2010), and Nicotiana attenuata (Wang et al., 2007). Among them, JA-Val was observed to accumulate rapidly during the local and systemic wound response in Arabidopsis (Koo et al., 2009). JA-Leu, JA-Val, and JA-Ala were demonstrated to promote the interaction of SlCOI1 and SlJAZs (Thines et al., 2007; Katsir et al., 2008). These results imply that the other JA amino acid conjugations besides JA-Ile may also play a role in JA signaling.

However, it is still unknown whether these JA amino acid conjugates function as bioactive jasmonates to trigger JA responses in planta. The cis configuration of C3 and C7 bonds in the JA cyclopentanone ring is unstable and easily changed into the nonfunctional configuration (Fonseca et al., 2009), which would seriously hamper the identification of novel JA active molecules. To eliminate the disturbance of different stereoisomers of JA amino acid conjugates, we designed and synthesized the CFA amino acid conjugates, which maintain the unchanged active configuration in the JA cyclopentanone ring and fully mimic the corresponding (+)-7-iso-JA-amino acid conjugates. We identified JA-Ala, JA-Val, JA-Leu, and JA-Met as the new active molecules of JA by demonstrating that four CFA-amino acid conjugates (CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, and CFA-Met) exhibited typical JA physiological bioactivities and shared the same perception mechanism with CFA-Ile and COR.

Previous studies have shown that JASMONATE RESISRAN1 (JAR1) encodes an enzyme that conjugates JA to several amino acid through a two-step mechanism involving adenylation and transferase activities (Staswick and Tiryaki, 2004; Suza and Staswick, 2008; Westfall et al., 2012). Kinetic analysis showed that JAR1 had a Km of 0.03 mm for Ile, a Km of 1.93 mm for Leu, and a Km of 2.49 for Val (Suza and Staswick, 2008). The high specificity of JAR1 for Ile is consistent with the preferential accumulation of JA-Ile in wounded leaves, which suggested that JAR1 could play an important role in the rapid increase in JA-Ile. However, the considerably higher accumulation of JA-Leu than JA-Val is inconsistent with the comparable Km value between Leu and Val, which suggested that the biosynthesis of JA-Leu in wounding treatment is regulated more complexly and cannot rule out the possible involvement of other JAR1-like acyl acid amido synthetases. Consistent with this, even though the contents of these bioactive JA conjugates in wounded jar1-1 leaves were decreased compared to those in wounded Col-0 leaves (Fig. 3A), the contents of these JA conjugates were still increased obviously by wounding treatment in wounded leaves of jar1-1 mutant, suggesting that some unknown jasmonate-amino synthetases were involved in the biosynthesis of those JA conjugates other than JAR1 (Supplemental Fig. S6).

We also investigated whether the bioactive CFA conjugates were able to restore root-growth inhibition phenotype of jar1-1 plants. As shown in Supplemental Figure S7, jar1-1 mutant seedlings exhibited similar inhibition effect of root growth with Col-0 seedlings under the treatment of these CFA conjugates. In contrast, the root length of jar1-1 seedling was significantly longer than that of Col-0 seedling in the presence of methyl jasmonate. These results suggested that CFA conjugates can function directly independent of JAR1, consistent with their direct recognition by JA receptor COI1.

Previous studies have shown that JA-responsive genes that are induced early after JA treatment are involved in signaling mechanisms including biosynthesis and signaling, whereas late-responsive genes are involved in ultimate jasmonate-modulated cellular responses, such as an antimicrobial plant defensing gene PDF1.2, which participates the defense against necrotrophic pathogens (Jung et al., 2007; Penninckx et al., 1998). However, the regulative mechanism of modulating the expression of related genes in early and late stage remains unknown. In present study, we found that CFA-Met exhibited stronger activity on inducing the expression of early JA-responsive genes than CFA-Ala overall, while CFA-Ala had stronger ability to induce the expression of late JA-responsive genes in comparison to CFA-Met (Fig. 4). Although the bioactivities of the corresponding JA amino acid conjugates ((+)-7-iso-JA-Met and (+)-7-iso-JA-Ala) might remain relatively low in our tests, these results suggested that these new JA active molecules could be involved in gene expression regulation of early and late JA-responsive gene.

More interestingly, these new JA active molecules exhibit distinct activities on promoting the interaction of COI1 and JAZ1 in diverse species (Fig. 5, C–G). Remarkably, the three COI1 paralogs in rice displayed great differences on perception of these new active JA conjugates (Fig. 5, E–G). The phylogenetic analysis of the OsCOI genes showed that OsCOI2 splits earlier than OsCOI1a and OsCOI1b by gene duplication, suggesting that OsCOI2 may have diverged from the two OsCOI1 genes (Lee et al., 2015). Consistently, in our pull-down assay, only OsCOI12 is capable of binding all five CFA conjugates, which is quite unlike OsCOI1a or OsCOI1b. In addition, although OsCOI1a and OsCOI1b share high similarities in phylogenetic relationship, they exhibited considerable differences in binding active JA and OsJAZ proteins, suggesting that only a few amino acid substitutions in the binding site would result in differences in their subfunctionalization. The complexities of evolution and regulation mechanism in rice jasmonate perception will need to be researched further.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutant coi1-1 was given by John G. Turner (Xie et al., 1998), and opr3 was given by John Browse (Stintzi and Browse, 2000). Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized and plated on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Sigma-Aldrich) added with 4% Suc, chilled at 4°C for 3 d, and then transferred to a growth room under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark (21°C to 23°C) photoperiod. For adult plants, seedlings were planted to soil after growing on MS medium for 7 to 10 d.

Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and rice (Oryza sativa cv Nipponbare) seedlings were grown on a 14-h-light/10-h-dark (26 to 28°C) photoperiod.

Protein Expression

For prokaryotic expression, pMAL-AtJAZ1-his, pMAL-OsJAZ1-his, and pMAL-SlJAZ1-his were constructed by cloning AtJAZ1, OsJAZ1, and SlJAZ1 from cDNAs of Arabidopsis Col-0, rice, and tomato, respectively, into pMAL-c2x (with a MBP tag before multiple cloning sites; New England Biolabs). For insect expression, pFast-AtCOI1, pFast-AtASK1, pFast-OsCOI1a, pFast-OsCOI1c, pFast-OsCOI12, and pFast-SlCOI1 were constructed by cloning AtCOI1, OsCOI1a, OsCOI1c, OsCOI12, and SlCOI1 from cDNA of Arabidopsis Col-0, rice, and tomato, respectively, into pFast (with a flag tag and a His tag before multiple cloning site; Invitrogen). Primers used are mentioned in Supplemental Table S3.

COI1 proteins were expressed using insect expression system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). For different COI1 protein expression, sf9 insect cells were coinfected with the recombinant baculovirus of Flag-6×His-COI1 and Flag-AtASK1. Cells were harvested after cultivating for 48 h. Proteins were purified with Ni-NTA agarose chromatography (Qiagen) and gel filtration (Superdex 200; GE).

JAZ proteins were expressed using a prokaryotic expression system. MBP-JAZ-His (AtJAZ1, SlJAZ1, OsJAZ1) was transformed into BL21 competent cells. Bacteria were cultured in 37°C for 3 h, and then transferred to 16°C for 16 h in present of 300 µm IPTG. Bacteria were harvested and proteins were purified with Ni-NTA agarose chromatography (Qiagen) and gel filtration (desalt, GE).

CFA Amino Acid Conjugate Synthesis

The syntheses of CFA-Gly, CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, CFA-Ile, CFA-Pro, CFA-Phe, CFA-Glu, CFA-Asp, CFA-Gln, and CFA-Lys are described as follows: compounds of H-Gly-OtBu, H-Ala-OtBu, H-Val-OtBu, H-Leu-OtBu, H-Ile-OtBu, H-Pro-OtBu, H-Phe-OtBu, H-Gln-OtBu, H-Glu(OtBu)-OtBu, H-Asp(OtBu)-OtBu, and H-Lys(Boc)-OtBu were condensed with CFA using EDC, DMAP, and Et3N in dichloromethane, respectively, and corresponding CFA-amino acid-OtBu (or CFA-amino acid(OtBu)-OtBu and CFA-Lys(Boc)-OtBu) products were obtained. Depriving the tertiary butyl ester of these compounds by trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) respectively, we obtained corresponding CFA-amino acid conjugates.

The syntheses of CFA-Met, CFA-Ser, CFA-Thr, CFA-Tyr, and CFA-Trp are described as follows: compounds of H-Met-OMe, H-Ser-OMe, H-Thr-OMe, H-Tyr-OMe, and H-Trp-OMe were condensed with CFA using EDC, DMAP, and Et3N in dichloromethane, respectively, CFA-amino acid-OMe products were obtained, and then the methyl ester was removed by lithium hydroxide in MeOH/H2O, to produce corresponding CFA-amino acid products.

The synthesis of CFA-His is described as follows: compound H-His(Trt)-OMe was condensed with CFA using EDC, DMAP, and Et3N in dichloromethane, CFA-His(Trt)-OMe were obtained, and then the methyl ester was removed by lithium hydroxide in MeOH/H2O to produce CFA-His(Trt)-OH, and in the end the Trt group was removed by TFA to yield CFA-His.

The syntheses of CFA-Cys, CFA-Asn, and CFA-Arg are described as follows: compounds Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Asn(Trt)-OH, and Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH were reacted with iodomethane catalyzing by cesium carbonate to produce Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OMe, Fmoc-Asn(Trt)-OMe, and Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OMe, respectively, then these compounds were rapidly reacted with piperidine in dimethylformamide, respectively, removing the Fmoc group to produce H-Cys(Trt)-OMe, H-Asn(Trt)-OMe, and H-Arg(Pbf)-OMe. By using DCC, HOBT, and Et3N, three compounds were condensed with CFA in dichloromethane to obtain CFA-Cys(Trt)-OMe, CFA-Asn(Trt)-OMe, and CFA-Arg(Pbf)-OMe, respectively, then the methyl ester was removed by lithium hydroxide in MeOH/H2O to produce CFA-Cys(Trt)-OH, CFA-Asn(Trt)-OH, and CFA-Arg(Pbf)-OH. In the end, the Trt/Pbf group were removed by TFA to yield corresponding CFA-amino acid products.

Nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry data of CFA amino acid conjugates are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

Wound Treatment and Quantification of JA Conjugates by Mass Spectrometry

Rosette leaves from 4-week-old Col-0 seedlings (not bolting) were crushed with a hemostat. Each leaf was wounded three times across the main leaf vein, made about 40% to 50% wounded area, and each plant had five or six leaves wounded. Each independent sample was comprised of about 100 leaves from 16 to 20 plants. Plants were put back into growth room for 1 h after wounding, and the wounded and unwounded leaves (from the untreated plants) were collected for the JA-amino acid conjugates concentration test. For tobacco and tomato, the fully expanded leaves (compound leaves for tomato) growing at node +1 and +2 from 45-d-old plants were crushed with a hemostat. Each leaf was wounded three or four times across the main leaf vein. Each independent sample was comprised of about 20 to 30 leaves from 10 to 15 plants. Plants were put back into growth room for 1 h after wounding and the wounded and unwounded leaves (from the untreated plants) were collected for JA-amino acid conjugates (JA-AA) concentration test. For rice, four-leaf-stage seedlings were treated with a hemostat, each leaf was crushed many times with about a 2 cm interval for two wounded parts across the main leaf vein. Each independent sample comprised about 30 to 40 leaves from 10 to 12 plants. Plants were put back into growth room for 1 h after wounding and the wounded and unwounded leaves (from the untreated plants) were collected for JA-AA quantification.

JA-AA content was measured by LC-MS/MS. All of samples were extracted with 80% methanol (0.1% formic acid), purified by a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters), and injected into a LC20AD-MS 8030 plus LC-MS/MS system (Shimadzu). A Shim-pack XR-ODS I column (2.0 mm I.D. × 75 mm, 2.2 μm; Shimadzu) was used. The mobile phase comprised solvent A (0.02% aqueous acetic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile) used in a gradient mode. The mass spectrometers were set to multiple monitoring mode using electrospray ionization with negative ion mode: for JA-Ala, mass-to-charge ratio of 280.3/88.05, quadrupole 1 prebias of 21 V, quadrupole 3 prebias of 30 V, collision energy of 22 eV; for JA-Val, mass-to-charge ratio of 307.9/116.1, quadrupole 1 prebias of 10 V, quadrupole 3 prebias of 19 V, collision energy of 21 eV; for JA-Met, mass-to-charge ratio of 339.9/148, quadrupole 1 prebias of 10 V, quadrupole 3 prebias of 14 V, collision energy of 19 eV; for JA-Ile, mass-to-charge ratio of 322.2/128.15, quadrupole 1 prebias of 16 V, quadrupole 3 prebias of 23 V, collision energy of 21 eV; For JA-Leu, mass-to-charge ratio of 322.3/172.05, quadrupole 1 prebias of 24 V, quadrupole 3 prebias of 16 V, collision energy of 17 eV. The final results of JA-AA conjugates in plant samples were calculated according to the calibration curves created using external standards.

Pull-Down Assay

Pull-down assay experiments were done as described previously (Thines et al., 2007). Total protein of HA-COI1 was extracted from transgenic HA-COI1 Arabidopsis seedlings (Yan et al., 2013) in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.8, 100 mm NaCl, 25 mm imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, 20 mm 2-mercapto-ethanol, 10 mm MG132, and the EDTA-free complete miniprotease inhibitor cocktail (Roche; Yan et al., 2009). Purified COI1 and purified JAZ proteins were expressed and purified according to the method described in the “Protein Expression” section. Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) was used to measure the protein concentration.

For pull-down assays by using total protein of HA-COI1 transgenic plants, roughly 100 μg purified MBP-AtJAZ1-His was used to bind to Ni-NTA beads and was incubated with total protein from 5 g HA-COI1 transgenic plant for 1 h at 4°C in the absence or presence of different molecules. For pull-down assays by using purified COI1 proteins, roughly 100 μg purified MBP-JAZ-His was used to bind to amylose resin and was incubated with 2 μg purified COI1 protein for 1 h at 4°C in the absence or presence of different molecules. COI1 protein was detected next with western-blot assay with an HA antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; H6908) or a flag antibody (Abmart).

Restoring Fertility of opr3 with CFA Conjugates and Pollen Germination Assay

The flowers of opr3 plants (about 40 d old) were treated with COR or different CFA conjugates (CFA-Ala, CFA-Val, CFA-Leu, CFA-Ile, or CFA-Met) of 400 µm, two times every day and for 2 d. The pictures of flowers were taken and the activity of pollen was tested on the third day. Pictures of branches were taken on the twelfth day, and pictures of silliques were taken when they were mature. For each time, every molecule treated at least three plants, and experiments were repeated for three times. For the pollen germination test, the germination medium was 10% (w/v) Suc, 0.01% boric acid, 1 mm MgSO4, 5 mm CaCl2, and 5 mm KCl, pH 7.5, with 1.5% agar, and the experiment was based on the method published previously (Qi et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2013).

Root Inhibition and Anthocyanin Quantification

Arabidopsis seeds were planted on MS (Sigma-Aldrich) medium plus different CFA conjugates or COR (1 µm or 10 µm), respectively, put into 4°C for 3 d, and transferred into growth room. The root length was measured and the anthocyanin accumulation was tested after growing for 7 or 10 d. Anthocyanin accumulation was tested following the method described previously (Shan et al., 2009). The quantity of anthocyanin was based on the formula (A535-A650)/FW (mg) × 1,000. Experiments were repeated three times.

Real-Time PCR

For real-time PCR, the 7-d-seedlings of Col-0 (grown on MS) were soaked into 1 µm CFA conjugates (water diluted) for 2 h or 8 h. RNA was then extracted, reverse transcription was performed, and the JA-responsive gene AtVSP1 expression was tested with real-time PCR (ABI7500 real-time PCR system). All of the experiments were repeated at least three times. Primers used are mentioned in Supplemental Table S3.

GUS Staining Assay

Seven-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings of WT::pVSP1-GUS (VSP1::GUS) (Zheng et al., 2006) were treated with solvent, 10 µm COR or CFA amino acid conjugates for 8 h. They were incubated overnight at 37°C in X-Gluc buffer (1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide, 10 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.5 mm potassium ferricyanide, 0.5 mm potassium ferrocyanide, pH 7.0, and 1% Triton X-100). Seventy percent ethanol was then used to wash the histochemically-stained seedlings and pictures were taken of them (Hu et al., 2013). Experiments were repeated for three times.

Seven-day-old JAZ1-GUS transgenic seedlings were treated with 1 µm CFA conjugates, respectively, for 10 h with or without 50 µm MG132 (Sigma). Seedlings were treated with MG132 2 h before being treated with CFA conjugates. Methods for GUS staining was described above. Experiments were repeated three times.

ITC

Thermodynamic parameters for the binding of the CFA conjugates to AtCOI1 protein were measured using isothermal titration calorimeter (Microcal ITC200). Samples of CFA conjugates and AtCOI1 protein were dissolved in buffer with 10 mm HEPES and 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4. Ten milligrams/milliliter AtCOI1 protein were put into the reaction cell, and 2.5 mm CFA conjugates were put in a syringe. Reactions were performed at 25°C; 20 injections of 0.75 μL titrant each time were used. Origin 7.0 software was used to calculate dissociation constants and other thermodynamic parameters by the analysis of data.

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative accession numbers for the genes mentioned in this article are as follows: COI1 (AT2G39940), ASK1 (AT1G75950), JAZ1 (AT1G19180), ATVSP1 (AT5G24780), OPR3 (AT2G06050), AOS (AT5G42650), LOX3 (AT1G17420), PDF1.2 (AT5G44420), THI2.1 (AT1G72260), LOX2 (AT3G45140), DFR (AT5G42800), and ACTIN8 (AT1G49240). For other genes in different species: SlCOI1 (AY423550.1), SlJAZ1 (NM_001247954.1), OsCOI1a (Os01G63420.1), OsCOI1b (Os05G37690.1), OsCOI12 (Os03G15880.1), and OsJAZ1 (AK061602).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. CFA exhibits no jasmonate activity.

Supplemental Figure S2. CFA-Ile exhibits the same bioactivity with COR.

Supplemental Figure S3. Synthesis of 20 kinds of CFA conjugates.

Supplemental Figure S4. Bioactive CFA conjugates promote JAZ1 degradation via the 26S proteasome pathway.

Supplemental Figure S5. Effect of nonbioactive CFA conjugates on root length inhibition and anthocyanin accumulation.

Supplemental Figure S6. Endogenous JA conjugates in jar1-1.

Supplemental Figure S7. The active CFA conjugates function independently of JAR1.

Supplemental Table S1. NMR and MS data of CFA amino acid conjugates.

Supplemental Table S2. Relative parameters of ITC assays.

Supplemental Table S3. Primers used for cloning and PCR.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- CFA

coronafacic acid

- COR

coronatine

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

References

- Campos ML, Kang JH, Howe GA (2014) Jasmonate-triggered plant immunity. J Chem Ecol 40: 657–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman RA, Mullet JE (1997) Biosynthesis and action of jasmonates in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48: 355–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca S, Chini A, Hamberg M, Adie B, Porzel A, Kramell R, Miersch O, Wasternack C, Solano R (2009) (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine is the endogenous bioactive jasmonate. Nat Chem Biol 5: 344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca S, Rosado A, Vaughan-Hirsch J, Bishopp A, Chini A (2014) Molecular locks and keys: the role of small molecules in phytohormone research. Front Plant Sci 5: 709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Thomas SG (2012) Gibberellin biosynthesis and its regulation. Biochem J 444: 11–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, Zhou W, Cheng Z, Fan M, Wang L, Xie D (2013) JAV1 controls jasmonate-regulated plant defense. Mol Cell 50: 504–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Higuchi M, Hashimoto Y, Seki M, Kobayashi M, Kato T, Tabata S, Shinozaki K, Kakimoto T (2001) Identification of CRE1 as a cytokinin receptor from Arabidopsis. Nature 409: 1060–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsir L, Schilmiller AL, Staswick PE, He SY, Howe GA (2008) COI1 is a critical component of a receptor for jasmonate and the bacterial virulence factor coronatine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7100–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo AJ, Gao X, Jones AD, Howe GA (2009) A rapid wound signal activates the systemic synthesis of bioactive jasmonates in Arabidopsis. Plant J 59: 974–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramell R, Atzorn RG, Schneider G, Miersch O, Bruckner C, Schmidt J, Sembdner G, Parthier B (1995) Occurrence and identification of jasmonic acid and its amino acid conjugates induced by osmotic stress in barley leaf tissue. J Plant Growth Regul 14: 29–36 [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Sakuraba Y, Lee T, Kim KW, An G, Lee HY, Paek NC (2015) Mutation of Oryza sativa CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1b (OsCOI1b) delays leaf senescence. J Integr Plant Biol 57: 562–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher K, Ng LM, Zhou XE, Soon FF, Xu Y, Suino-Powell KM, Park SY, Weiner JJ, Fujii H, Chinnusamy V, et al. (2009) A gate-latch-lock mechanism for hormone signalling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature 462: 602–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Miyakawa T, Sawano Y, Kubota K, Kang HJ, Asano A, Miyauchi Y, Takahashi M, Zhi Y, Fujita Y, et al. (2009) Structural basis of abscisic acid signalling. Nature 462: 609–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N, Hitomi K, Arvai AS, Rambo RP, Hitomi C, Cutler SR, Schroeder JI, Getzoff ED (2009) Structural mechanism of abscisic acid binding and signaling by dimeric PYR1. Science 326: 1373–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C, Lyou SH, Yeu S, Kim MA, Rhee S, Kim M, Lee JS, Choi YD, Cheong JJ (2007) Microarray-based screening of jasmonate-responsive genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep 26: 1053–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normanly J. (2010) Approaching cellular and molecular resolution of auxin biosynthesis and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak O, Bujacz GD, Fujimoto Y, Hashimoto Y, Jelen F, Otlewski J, Sikorski MM, Jaskolski M (2006) Crystal structure of Vigna radiata cytokinin-specific binding protein in complex with zeatin. Plant Cell 18: 2622–2634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx IA, Thomma BP, Buchala A, Métraux JP, Broekaert WF (1998) Concomitant activation of jasmonate and ethylene response pathways is required for induction of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10: 2103–2113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T, Song S, Ren Q, Wu D, Huang H, Chen Y, Fan M, Peng W, Ren C, Xie D (2011) The Jasmonate-ZIM-domain proteins interact with the WD-Repeat/bHLH/MYB complexes to regulate Jasmonate-mediated anthocyanin accumulation and trichome initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 23: 1795–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J, Dupeux F, Round A, Antoni R, Park SY, Jamin M, Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL, Márquez JA (2009) The abscisic acid receptor PYR1 in complex with abscisic acid. Nature 462: 665–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santino A, Taurino M, De Domenico S, Bonsegna S, Poltronieri P, Pastor V, Flors V (2013) Jasmonate signaling in plant development and defense response to multiple (a)biotic stresses. Plant Cell Rep 32: 1085–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JS, Joo J, Kim MJ, Kim YK, Nahm BH, Song SI, Cheong JJ, Lee JS, Kim JK, Choi YD (2011) OsbHLH148, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, interacts with OsJAZ proteins in a jasmonate signaling pathway leading to drought tolerance in rice. Plant J 65: 907–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan X, Zhang Y, Peng W, Wang Z, Xie D (2009) Molecular mechanism for jasmonate-induction of anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 60: 3849–3860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada A, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Nakatsu T, Nakajima M, Naoe Y, Ohmiya H, Kato H, Matsuoka M (2008) Structural basis for gibberellin recognition by its receptor GID1. Nature 456: 520–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE, Tiryaki I (2004) The oxylipin signal jasmonic acid is activated by an enzyme that conjugates it to isoleucine in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 2117–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE. (2009) The tryptophan conjugates of jasmonic and indole-3-acetic acids are endogenous auxin inhibitors. Plant Physiol 150: 1310–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stintzi A, Browse J (2000) The Arabidopsis male-sterile mutant, opr3, lacks the 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase required for jasmonate synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10625–10630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suza WP, Rowe ML, Hamberg M, Staswick PE (2010) A tomato enzyme synthesizes (+)-7-iso-jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine in wounded leaves. Planta 231: 717–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suza WP, Staswick PE (2008) The role of JAR1 in Jasmonoyl-L: -isoleucine production during Arabidopsis wound response. Planta 227: 1221–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Calderon-Villalobos LI, Sharon M, Zheng C, Robinson CV, Estelle M, Zheng N (2007) Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446: 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines B, Katsir L, Melotto M, Niu Y, Mandaokar A, Liu G, Nomura K, He SY, Howe GA, Browse J (2007) JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCF(COI1) complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vick BA, Zimmerman DC (1984) Biosynthesis of jasmonic Acid by several plant species. Plant Physiol 75: 458–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakuta S, Suzuki E, Saburi W, Matsuura H, Nabeta K, Imai R, Matsui H (2011) OsJAR1 and OsJAR2 are jasmonyl-L-isoleucine synthases involved in wound- and pathogen-induced jasmonic acid signalling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409: 634–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Halitschke R, Kang JH, Berg A, Harnisch F, Baldwin IT (2007) Independently silencing two JAR family members impairs levels of trypsin proteinase inhibitors but not nicotine. Planta 226: 159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wu J (2013) The essential role of jasmonic acid in plant-herbivore interactions--using the wild tobacco Nicotiana attenuata as a model. J Genet Genomics 40: 597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C. (2014) Action of jasmonates in plant stress responses and development--applied aspects. Biotechnol Adv 32: 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Hause B (2013) Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. An update to the 2007 review in Annals of Botany. Ann Bot (Lond) 111: 1021–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall CS, Zubieta C, Herrmann J, Kapp U, Nanao MH, Jez JM (2012) Structural basis for prereceptor modulation of plant hormones by GH3 proteins. Science 336: 1708–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie DX, Feys BF, James S, Nieto-Rostro M, Turner JG (1998) COI1: an Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science 280: 1091–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan W, Murphy E, Beeckman T, Audenaert D, De Smet I (2013) Synthetic molecules: helping to unravel plant signal transduction. J Chem Biol 6: 43–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Suzuki T, Terada K, Takei K, Ishikawa K, Miwa K, Yamashino T, Mizuno T (2001) The Arabidopsis AHK4 histidine kinase is a cytokinin-binding receptor that transduces cytokinin signals across the membrane. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 1017–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Li H, Li S, Yao R, Deng H, Xie Q, Xie D (2013) The Arabidopsis F-box protein CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 is stabilized by SCFCOI1 and degraded via the 26S proteasome pathway. Plant Cell 25: 486–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Zhang C, Gu M, Bai Z, Zhang W, Qi T, Cheng Z, Peng W, Luo H, Nan F, et al. (2009) The Arabidopsis CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 protein is a jasmonate receptor. Plant Cell 21: 2220–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Zhai Q, Sun J, Li CB, Zhang L, Li H, Zhang X, Li S, Xu Y, Jiang H, et al. (2006) Bestatin, an inhibitor of aminopeptidases, provides a chemical genetics approach to dissect jasmonate signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 141: 1400–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.