The phytocalpain DEFECTIVE KERNEL1 effects physical changes in the cell wall and expression of cell wall-related genes in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Abstract

The plant epidermis is crucial to survival, regulating interactions with the environment and controlling plant growth. The phytocalpain DEFECTIVE KERNEL1 (DEK1) is a master regulator of epidermal differentiation and maintenance, acting upstream of epidermis-specific transcription factors, and is required for correct cell adhesion. It is currently unclear how changes in DEK1 lead to cellular defects in the epidermis and the pathways through which DEK1 acts. We have combined growth kinematic studies, cell wall analysis, and transcriptional analysis of genes downstream of DEK1 to determine the cause of phenotypic changes observed in DEK1-modulated lines of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). We reveal a novel role for DEK1 in the regulation of leaf epidermal cell wall structure. Lines with altered DEK1 activity have epidermis-specific changes in the thickness and polysaccharide composition of cell walls that likely underlie the loss of adhesion between epidermal cells in plants with reduced levels of DEK1 and changes in leaf shape and size in plants constitutively overexpressing the active CALPAIN domain of DEK1. Calpain-overexpressing plants also have increased levels of cellulose and pectins in epidermal cell walls, and this is correlated with the expression of several cell wall-related genes, linking transcriptional regulation downstream of DEK1 with cellular effects. These findings significantly advance our understanding of the role of the epidermal cell walls in growth regulation and establish a new role for DEK1 in pathways regulating epidermal cell wall deposition and remodeling.

Calpains are members of the papain superfamily of Cys proteases and can be found in almost all eukaryotes and in some bacteria (Ono and Sorimachi, 2012). DEFECTIVE KERNEL1 (DEK1) belongs to a subfamily of plant-specific calpains, known as phytocalpains, which have highly modified structures compared with classical animal calpains (Margis and Margis-Pinheiro, 2003; Wang et al., 2003; Ahn et al., 2004; Ono and Sorimachi, 2012). Like other phytocalpains, DEK1 has a predicted structure including between 21 and 24 transmembrane (TM) domains at the N terminus (Kumar et al., 2010), a juxtamembrane linker domain, and a cytoplasmic C-terminal CALPAIN domain (Lid et al., 2002). Whereas classical calpains are located in the cytoplasm, full-length DEK1 localizes to the plasma membrane (Johnson et al., 2008).

In animals, the catalytic activity of calpains depends on the presence of calcium (Croall and Ersfeld, 2007), and the autocatalytic removal of the N-terminal domain results in a reduction in the calcium requirement and is thought to correlate with calpain activation (García Díaz et al., 2006). As in animal calpains, DEK1 undergoes autolytic cleavage events in the N terminus that, in the case of DEK1, release the CALPAIN domain into the cytoplasm. These events have been proposed to be important for the activation of the DEK1 CALPAIN domain (Johnson et al., 2008). Animal calpains are involved in a wide range of biological processes, including apoptosis, necrosis, and ageing. They have been implicated in various pathologies such as arterial hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and tumor growth and, therefore, have become major targets of interest for therapeutic applications (Croall and Ersfeld, 2007; Siklos et al., 2015). In contrast, to date, the molecular pathways acting downstream of DEK1 are poorly understood, and no direct targets have been identified.

Several studies have shown the importance of DEK1 in the specification and maintenance of the epidermal cell layer (Becraft et al., 2002; Ahn et al., 2004; Roeder et al., 2012; Galletti et al., 2015). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), dek1 knockout mutants are early embryo-lethal, so the role of DEK1 has largely been inferred through the use of plants in which levels of DEK1 have been reduced. These include lines showing RNA interference-mediated gene silencing and an ethyl methanesulfonate-generated weak allele, dek1-4 (Johnson et al., 2005, 2008; Roeder et al., 2012; Galletti et al., 2015). Changes in epidermal cells are observed in the dek1-4 mutant, including a near absence of giant cells in sepals (Roeder et al., 2012) and reduced lobing in cotyledon pavement cells (Galletti et al., 2015). DEK1 has been shown to promote and maintain the differentiated epidermal state by indirectly affecting the expression of epidermis-specific transcription factors (Johnson et al., 2005; Galletti et al., 2015). As reduced DEK1 activity often results in cell separation in the epidermis, DEK1 has been proposed to regulate the zone of epidermal cell-cell contact. Consistent with this, increased callose levels were observed at epidermal cell boundaries in weak loss-of-function mutants in Arabidopsis, likely due to feedback mechanisms counteracting cell separation (Galletti et al., 2015).

Plant cell walls not only act as the glue between plant cells but also play an important role in permitting the generation of turgor pressure required for growth and enabling controlled cell expansion (Cosgrove, 2005; Wolf et al., 2012a). The epidermal outer cell walls have been shown to play an important role in growth control, for example, being differentially thickened in hypocotyl cells ready to undergo cell expansion (Derbyshire et al., 2007). Likewise, in the shoot apical meristem, zones of reduced cell wall stiffness determine sites of organ outgrowth (Fleming et al., 1997; Peaucelle et al., 2011). How these changes are regulated across layers of growing cells is still largely unknown. Primary plant cell walls are complex mixtures of polysaccharides (approximately 90%) and some protein (approximately 10%), and it is estimated that more than 2,000 genes are required for their synthesis and maintenance (McCann and Rose, 2010). Cellulose is the major fibrillar component of a cell wall and contributes to the strength of the wall (Cosgrove, 2005; Doblin et al., 2010). Flexible matrix phase polysaccharides, such as xyloglucans, heteroxylans, and/or the gel-forming pectins, act as plasticizers between the long strands of cellulose to keep the growing cell walls both pliant and strong (Cosgrove, 1999, 2014; Ridley et al., 2001; Mazumder et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). Pectins can constitute up to 40% of the primary cell wall in growing dicot cells and have well-established roles, including promoting cell-cell adhesion (Caffall and Mohnen, 2009; Ogawa et al., 2009; Bar-Peled et al., 2012), providing a source for oligosaccharide signaling molecules for growth, development, and defense (Ridley et al., 2001; Galletti et al., 2009, 2011; Ferrari et al., 2013), and as a hydration polymer affecting wall rheology (Harholt et al., 2010).

The major form of pectin is homogalacturonan (HG), which is synthesized in the Golgi apparatus, heavily substituted with methylester groups, and secreted into the apoplast (Mohnen, 2008; Driouich et al., 2012). In the apoplast, HG can be demethylesterified by pectin methylesterases (PMEs), and this process can be spatially regulated by pectin methylesterase inhibitors (PMEIs; Micheli, 2001; Giovane et al., 2004; Di Matteo et al., 2005; Juge, 2006). Together, PMEs and PMEIs maintain the methylesterification status of pectins in the cell wall, which in turn controls the gelling properties of pectins and, hence, plant growth (Valentin et al., 2010). Depending on the cellular context, the regulation of HG methylesterification via PME can promote either wall stiffening by the formation of pectin cross-links or wall loosening through wall hydration, wall degradation, and/or wall signaling (Moustacas et al., 1991; Catoire et al., 1998; Peaucelle et al., 2008).

Studies of DEK1 in the moss Physcomitrella patens have led to the proposal that the extracellular loop within the large transmembrane domain (MEM domain) of DEK1 most likely acts as a sensor to detect the stimuli from the external environment (Demko et al., 2014). The N-terminal domain of DEK1 is proposed to regulate the activation of the functional cytoplasmic CALPAIN domain and allow CALPAIN to trigger downstream signaling, either locally or at the level of transcription (Johnson et al., 2008). Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpressing the CALPAIN domain (calpain oe) results in growth defects that suggest a bypass of normal DEK1 regulation (Johnson et al., 2008). Similar complementation studies with the CALPAIN domain alone suggest that both P. patens and Arabidopsis DEK1 share common molecular mechanisms that rely on CALPAIN Cys protease activity and its spatial and temporal regulation (Johnson et al., 2008; Perroud et al., 2014). Transcriptomic studies in Arabidopsis overexpressing the CALPAIN domain (Johnson et al., 2008) and P. patens lacking the dek1 gene (Demko et al., 2014) show that cell wall-related genes are overrepresented in the list of genes whose expression is significantly misregulated compared with wild-type controls.

Here, we show that phenotypes associated with changes in DEK1 activity are largely a result of altered cell expansion and growth coordination. Changing DEK1 activity leads to alterations both in the junctions between cells and in cell wall thickness and polysaccharide composition in the leaf epidermis, consistent with alterations in the expression levels of cell wall-related genes as shown by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis.

RESULTS

Overexpression of CALPAIN and Reduced Levels of DEK1 Result in Altered Plant Growth

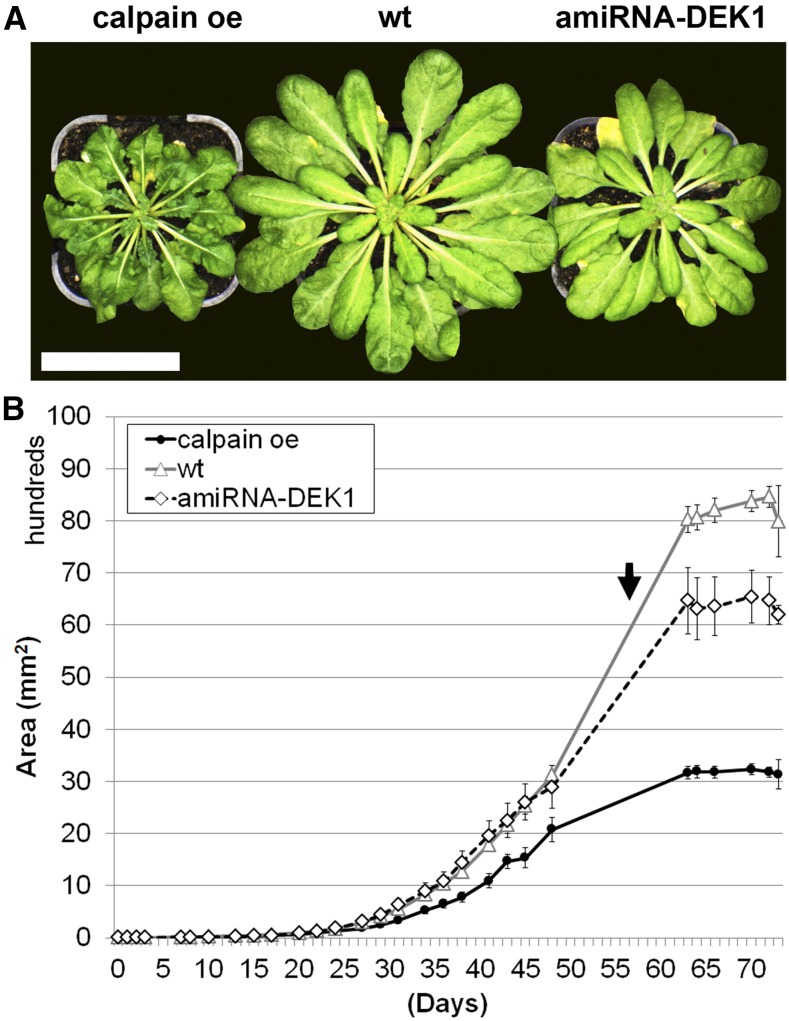

To dissect the role of DEK1 in growth regulation over time, we undertook high-resolution phenotyping, including kinematic and morphological studies, of leaf growth. We investigated 17-d-old seedlings of homozygous dek1-3 mutant plants complemented with the CALPAIN domain (calpain oe; Johnson et al., 2008) and lines constitutively expressing an artificial microRNA targeting the DEK1 transcript (amiRNA-DEK1; Galletti et al., 2015) and compared them with the wild type. The levels of CALPAIN transcript were assessed by RT-qPCR and showed a 15-fold increase in the calpain oe line and a 2.5-fold reduction in CALPAIN levels in amiRNA-DEK1, as described previously (Johnson et al., 2008; Galletti et al., 2015). When grown in short-day conditions, gross morphological abnormalities can be observed in calpain oe plants, including rumpled, dark green leaves, shorter petioles, and a more compact rosette (Johnson et al., 2008; Fig. 1A). Nondestructive analysis of the total rosette leaf area over time showed that calpain oe plants have significantly smaller rosettes compared with the wild type due to changes in leaf shape (Fig. 1B) with no change in leaf number (Fig. 1A). Differences between calpain oe and wild-type leaf areas become apparent after 25 d of growth and result in plants approximately 60% smaller than wild-type plants. Analysis of the absolute growth rate, corresponding to the plant area that is formed during a certain unit of time, peaks at day 58 in the wild type. In calpain oe, the absolute growth rate peaks earlier than in either wild-type or amiRNA-DEK1 plants, at day 50 (Supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that calpain oe plants develop phenologically faster. The rate of growth also is reduced in calpain oe lines (Supplemental Fig. S1). No clear rosette phenotype was observed in amiRNA-DEK1 plants compared with the wild type until 45 d of growth (Fig. 1A). At maturity, the absolute growth rate of amiRNA-DEK1 plants slowed, resulting in an approximately 20% smaller rosette area compared with the wild type (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Rosette phenotypes of calpain oe, wild-type (wt), and amiRNA-DEK1 plants and kinematic analysis of rosette area. A, Representative image of 60-d-old plants (taken from the time point shown by the arrow in B). Bar = 50 mm. B, Nondestructive measurement of rosette area (mm2) over time shows changes in total leaf area and the timing of growth in calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 plants relative to wild-type controls. Error bars denote se; n = 20.

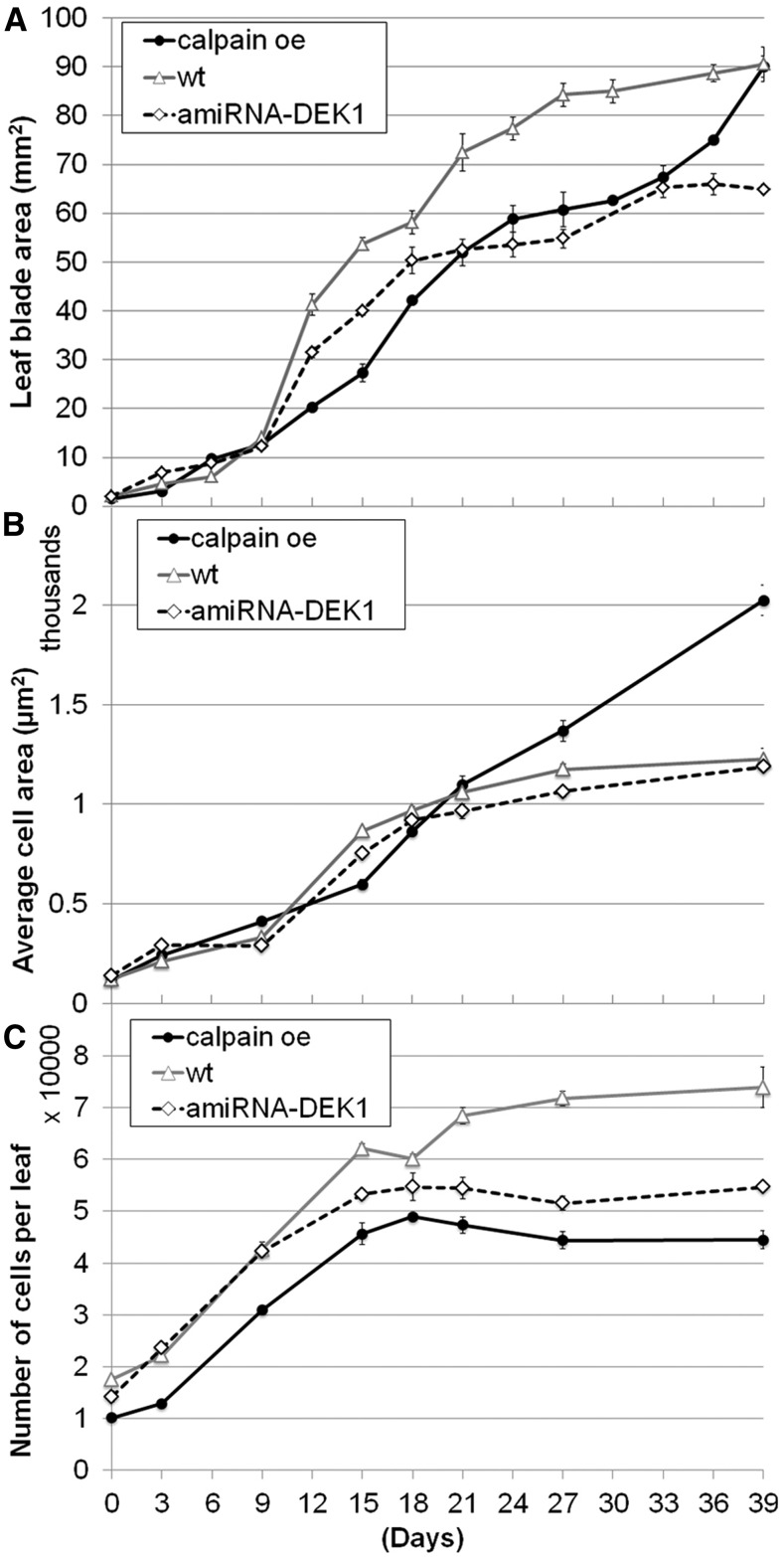

To investigate these effects on leaf development in greater detail, kinematic analyses were performed using the sixth leaf (De Veylder et al., 2001). As the calpain oe leaves are rumpled, it was necessary to cut the leaf down the midvein to allow flattening of the leaf blade to more accurately reflect true leaf area (Johnson et al., 2008). In wild-type plants, the leaf blade area of the sixth leaf expanded exponentially until day 15, after which expansion rates decreased and mature size was reached at day 27 (Fig. 2A). In the calpain oe leaf, the growth is irregular, with a reduced rate of cell division and an extended expansion phase (Fig. 2). At day 39, the overall size of the leaf in calpain oe is similar to that of the wild type; however, it appears to be still undergoing expansion. These results suggest that the nondestructive analysis gave an underestimation of leaf area due to the rumpling of the leaves (Fig. 1B). The sixth leaf of amiRNA-DEK1 plants shows a similar growth pattern to wild-type leaves until day 9, after which the growth rate slows more rapidly than in the wild type, resulting in a smaller mature leaf size (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Kinematic analysis of leaf growth in the sixth leaf of calpain oe, wild-type (wt), and amiRNA-DEK1 plants. A, Leaf blade area. B, Average epidermal cell size from the abaxial side of the leaf. C, Average epidermal cell number from the abaxial side of the leaf. Error bars denote se; n = 4 to 6.

The epidermis is proposed to play a key role in the regulation of plant growth, and previous studies have shown that DEK1 levels affect the shape and size distribution of cotyledon epidermal cells but not their average size (Galletti et al., 2015). Therefore, we measured rates of cell division (number) and cell expansion (size) in the epidermal cells in the sixth leaf of the calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 lines over time. Although the average size of cells in the epidermis of amiRNA-DEK1 leaves was comparable to that in the wild type, there was greater variability in the size distribution during the expansion phase of leaf development (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S2). These data suggest that a reduction in the number of epidermal cells per leaf is responsible for the smaller leaf size. Similar to the leaf blade area, the number of cells first increases exponentially, followed by a gradual increase until the final number of cells per leaf is reached (Fig. 2C). Our results indicate that the duration of the proliferation phase is reduced in amiRNA-DEK1, resulting in a 1.4-fold reduction in cell number per leaf compared with wild-type plants at day 39. Unlike the wild type and amiRNA-DEK1, calpain oe shows an almost constant increase in epidermal cell size throughout the whole growth phase (Fig. 2B). The number of cells per leaf in calpain oe is similar to that in the wild type until day 15, after which the number plateaus (Fig. 2C). These observations suggest that increased levels of CALPAIN affect the timing and rate of cell expansion. Increased cell expansion in calpain oe masks the effects of an earlier exit from proliferation, resulting in a similar leaf size to the wild type. A decrease in DEK1 levels leads to a shorter proliferation phase with no changes in expansion and results in smaller leaves.

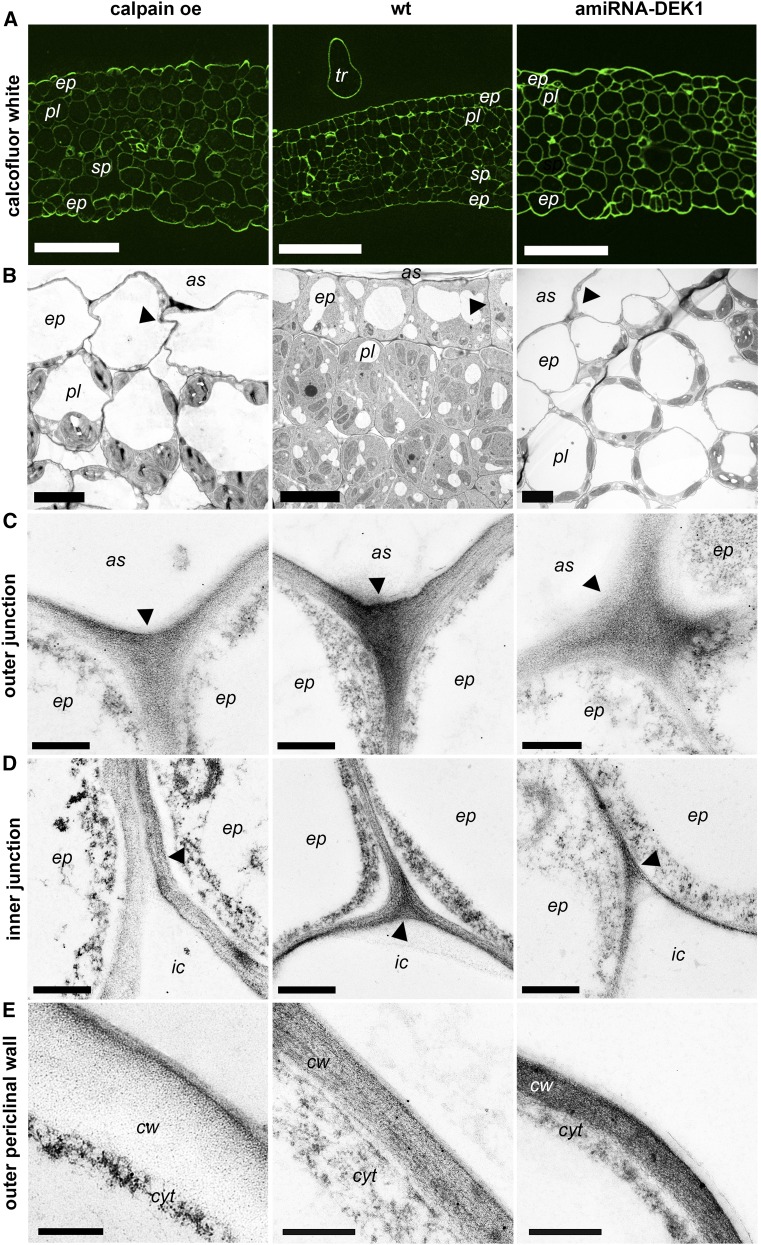

Increased Levels of CALPAIN Result in Changes in Epidermis Cellular Morphology

Consistent with studies in cotyledons (Galletti et al., 2015), we observed reduced lobing in epidermal leaf pavement cells of amiRNA-DEK1 compared with the wild type. Changes in leaf thickness, cell shape, size, and number also have been observed in underlying layers of leaves from mature calpain oe and weakly complemented dek1 plants (Johnson et al., 2008). Cross sections of leaf 4 of 17-d-old plants were stained with Calcofluor White to visualize the cellular morphology in the epidermal and other cell layers at an early stage in development. The leaves of calpain oe are thicker than wild-type layers due to the presence of two palisade mesophyll layers with less uniform cell size and shape (Fig. 3, A and B) rather than one layer of palisade mesophyll with vertically elongated cells, as seen in the wild type (Johnson, et al., 2008; Fig. 3, A and B). One layer of palisade was observed in amiRNA-DEK1 lines; however, its cells exhibit a rounder shape than do wild-type cells (Fig. 3, A and B), and amiRNA-DEK1 leaves appear thicker than wild-type leaves due to larger air spaces between mesophyll cells.

Figure 3.

Cellular morphology and transmission electron micrographs derived from cross sections of the adaxial side of leaf 4 from 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type (wt), and amiRNA-DEK1 plants. A, Calcofluor White staining shows increased leaf thickness in calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1. Bars = 50 µm. B, Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing bigger and less uniform palisade cell shape in calpain oe and rounded, less densely packed palisade cells in amiRNA-DEK1. Altered contact between epidermal cells in the adaxial layer of calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 leaves compared with the wild type also can be observed (arrowheads). Bars = 5 µm. C and D, Representative TEM transverse sections of outer (C) and inner (D) cell junctions (arrowheads) show severely reduced junction in amiRNA-DEK1 (C) and inner junction defects in calpain oe, where the anticlinal walls are not fully in contact (D). Bars = 0.5 µm. E, TEM sections of the outer periclinal walls of epidermis show increased wall thickness in calpain oe. Bars = 0.4 µm. as, Air space; cw, cell wall; cyt, cytoplasm; ep, epidermis; ic, intercellular space; pl, palisade.

Previous studies had shown that a loss of adhesion between epidermal cells can occur in plants with reduced DEK1, and Galletti et al. (2015) observed a less uniform height (defined below) of epidermal cell contact zones in dek1-4 cotyledons. We used TEM to investigate the cell-cell contact zones in the epidermal layer of calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 lines in 17-d-old leaves to determine if they had altered morphology compared with the wild type. Following the method of Galletti et al. (2015), the cell-cell contact zone height/junction lengths were measured from the contact point in the outer surface of epidermis (outer junction; Fig. 3C; Supplemental Fig. S3A) to the contact points in the inner surface (inner junction; Fig. 3D). Our study of 17-d-old leaves shows that, unlike the wild type, which typically shows little variance in contact zone height, amiRNA-DEK1 epidermal cells show greater variances in height of the cell-cell contact zone in both the adaxial and abaxial epidermis (Supplemental Fig. S3). This is consistent with the results of Galletti et al. (2015) in cotyledons. The altered contact zone in this line is likely due to both reduced cell adhesion and differences in cell size (Fig. 3B). Altered contact zones also were observed in calpain oe lines, which had a reduced contact zone height compared with the wild type. This may be due to uneven epidermal cell size and shape, which results in inner junction defects, where the walls between two epidermis cells are not completely in contact (Fig. 3D). Although contact zone height is reduced in calpain oe plants, the shape of the walls between cells is wavy, suggesting a greater cell-cell contact area (Fig. 3B).

Unlike the wild type and calpain oe, which have a continuous epidermal layer, in amiRNA-DEK1 plants, cells from the underlying palisade layer appear to encroach on the spaces left between the epidermal cells (Fig. 3B). The outer junction zone of the cells, therefore, is altered from the usual Y shape (Fig. 3C), appears less electron-dense, and cells are more distant from one another than in the wild type. Unlike wild-type cells, where the cell junction is a uniform size, in amiRNA-DEK1 plants, a small contact point between cells was frequently seen in both the adaxial (Fig. 3, B and C) and abaxial (Supplemental Fig. S3) epidermis. Where cells in the epidermis do contact an air space is frequently seen at the inner junction, and a reduced thickness of the wall between cells is observed (Fig. 3D). Given the observed cell adhesion phenotypes and a previous report showing changes in the expression of cell wall-related genes in calpain oe plants (Johnson et al., 2008), we focused subsequent analyses on the effects of changing DEK1 activity on the cell walls.

Altered Levels of DEK1 CALPAIN Affect Cell Wall Thickness, Most Notably in Outer Periclinal Walls

Dramatically thicker outer epidermal cell walls are observed in calpain oe leaves compared with wild-type and amiRNA-DEK1 leaves (Fig. 3E; Table I). The outer periclinal cell walls of both the adaxial and abaxial epidermis of calpain oe leaves are significantly thicker, and this becomes even more pronounced in leaves of 42-d-old plants (Table I). A significant increase in cell wall thickness also was seen in anticlinal and inner periclinal walls of calpain oe epidermal cells and in trichome cell walls (Table I). A significant reduction in epidermis cell wall thickness was observed only on the adaxial side of amiRNA-DEK1 leaves of 17-d-old plants compared with wild-type plants, occurring in the outer and inner periclinal cell walls, with no difference seen in the anticlinal wall at this stage (Table I). No differences in the thickness of palisade and mesophyll cell walls was observed in calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 compared with the wild type (Table I).

Table I. Cell wall thickness measurements (µm) from transverse sections of leaf 4 from calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

se is less than 0.01 in each case and, therefore, not reported. Boldface values are statistically significant at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA.

| Measurement | 17-d-Old Plants |

42-d-Old Plants |

n | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| calpain oe | Wild Type | amiRNA-DEK1 | calpain oe | Wild Type | amiRNA-DEK1 | ||

| Epidermal walls | |||||||

| Outer periclinal (adaxial) | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 1.20 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 10 |

| Outer periclinal (abaxial) | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 1.37 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 10 |

| Anticlinal (adaxial) | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 10 |

| Inner periclinal (adaxial) | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 10 |

| Ratio of epidermal wall thickness | |||||||

| Outer periclinal (adaxial) | 1.84 | 1 | 0.65 | 2.23 | 1 | 0.30 | 10 |

| Outer periclinal (abaxial) | 1.61 | 1 | 1.28 | 5.71 | 1 | 1.31 | 10 |

| Mesophyll walls | |||||||

| Palisade | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 10 |

| Spongy | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 10 |

| Trichome | 2.12 | 1.24 | 1.15 | – | – | – | 10 |

Changes in DEK1 Levels Affect Cell Wall Content and Composition

Changes in cell wall thickness in epidermal cells of plants with altered DEK1 activity may be related to changes in cell wall deposition and/or composition. Analysis of the monosaccharide and polysaccharide composition of the whole leaf cell walls was performed on the alcohol-insoluble residue fraction from the four youngest rosette leaves of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants. We found no obvious differences in arabinan, type I AG, type II AG, homogalacturonan, RGI/II, glucuronoxylan, heteromannan, xyloglucan, and cellulose levels from linkage analysis (Supplemental Fig. S4). Monosaccharide analysis also showed no differences in Rha, Ara, Xyl, Man, Glc, Gal, GlcA, and GalA levels from 17-d-old transgenic lines compared with the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S4). However, the fact that the epidermal layer makes up only around 20% of the total leaf volume is likely to significantly mask/dilute the changes in a total leaf alcohol-insoluble residue analysis; hence, microscopy using antibodies raised against cell wall epitopes was used to detect changes in polysaccharide composition/distribution at the cellular level.

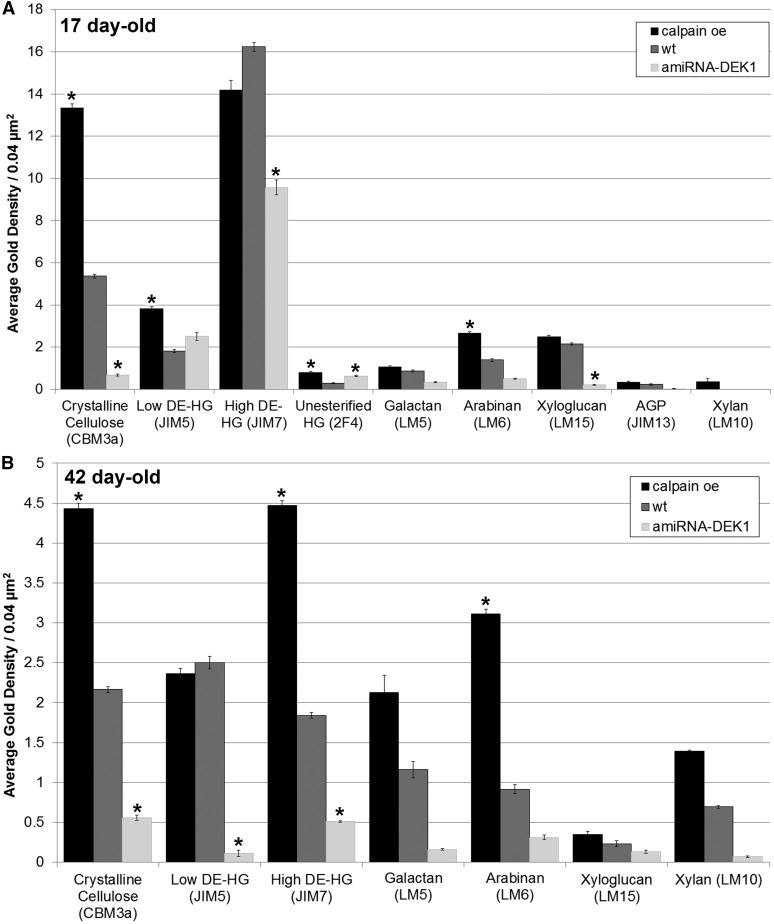

In this study, the fourth leaf from 17-d-old plants, where changes in wall thickness are already apparent (Fig. 3E), and the fourth leaf of 42-d-old plants were used to investigate the labeling pattern of cell wall epitopes in the epidermal cell layer (Fig. 4). In 17-d-old plants, calpain oe shows a significant increase in epitope labeling density with probes for crystalline cellulose, low degree of methyl-esterified (DE) HG, and arabinan, while increases in unesterified HG were observed in both calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 compared with the wild type (Fig. 5A). The amiRNA-DEK1 lines showed decreased labeling of crystalline cellulose, high-DE HG, and xyloglucan (Fig. 5A). In 42-d-old plants, labeling of both high- and low-DE HG are significantly reduced in amiRNA-DEK1 and in calpain oe, while an increase in labeling of high-DE HG is observed (Fig. 5B).

Figure 4.

Measurement of the immunogold density of cell wall epitopes without demasking treatment in TEM transverse sections of periclinal epidermal walls from leaf 4 of 17- and 42-d-old calpain oe, wild-type (wt), and amiRNA-DEK1 plants. A, The 17-d-old calpain oe plant shows increased crystalline cellulose, low-DE and unesterified HG, and arabinan. In addition, amiRNA-DEK1 shows increased unesterified HG and reduced crystalline cellulose, high-DE HG, and xyloglucan. B, The 42-d-old calpain oe plant shows increased crystalline cellulose, high-DE HG, and arabinan. In addition, amiRNA-DEK1 shows decreased crystalline cellulose and low- and high-DE HG. Asterisks indicate statistically significant values at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA; n = 10 to 15 epidermal cells from two biological replicates. Error bars denote se.

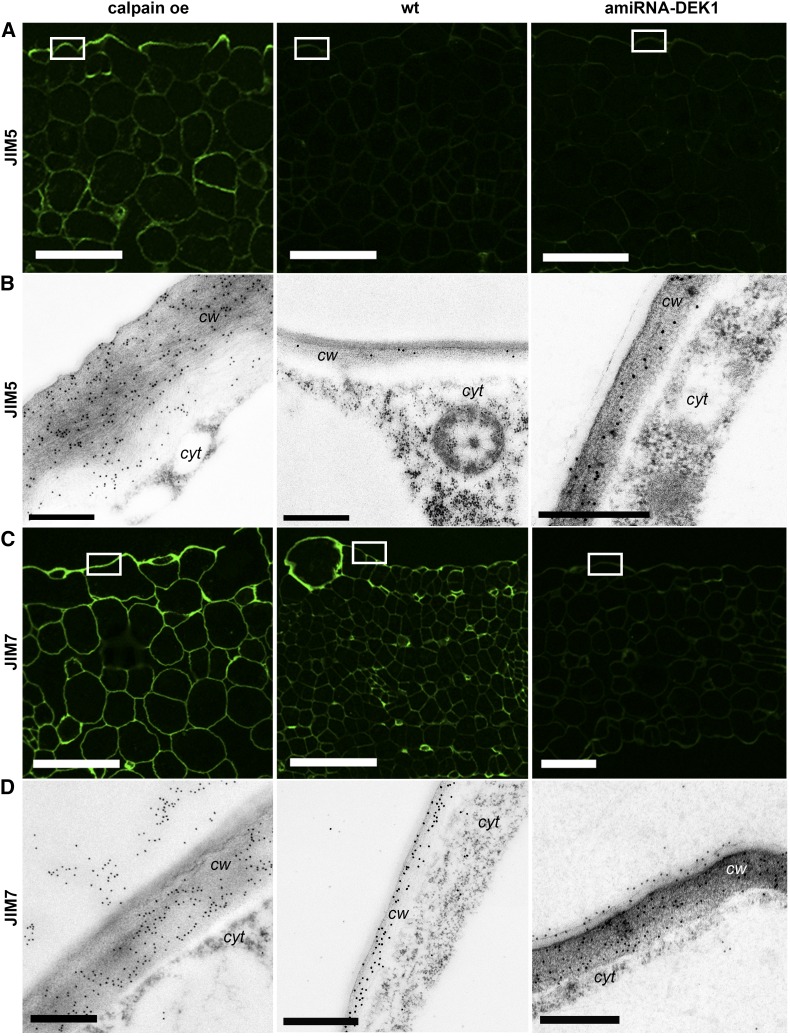

Figure 5.

Detection of pectin epitopes in cross sections derived from leaf 4 of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type (wt), and amiRNA-DEK1 plants. A and C, Immunofluorescence labeling with JIM5 (low-DE pectin; A) and JIM7 (high-DE pectin; C) antibodies shows higher fluorescence intensity in calpain oe walls compared with the wild type and amiRNA-DEK1. Bars = 25 µm. B and D, TEM immunogold labeling with JIM5 (B) and JIM7 (D) in the outer periclinal epidermis walls (white boxes in A and C, respectively) shows significantly increased gold labeling (see Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. S5) in calpain oe. cw, Cell wall; cyt, cytoplasm. Bars = 0.5 µm.

To further investigate if changes in the labeling of pectin epitopes occurs in other cell types, fluorescence intensity was observed using the anti-HG antibody JIM5, which recognizes low-DE HG and also can bind to unesterified HG (Knox et al., 1990). Higher fluorescence intensity was observed in all cell layers of the fourth leaf of 17-d-old calpain oe compared with wild-type and amiRNA-DEK1 plants (Fig. 5A). Immunofluorescence labeling with the JIM7 antibody, which recognizes partially methylesterified epitopes of HG but does not bind to unesterified HG, similarly showed higher fluorescence intensity in calpain oe leaves compared with wild-type leaves (Fig. 5C). In contrast, amiRNA-DEK1 leaves showed reduced fluorescence with JIM7 (Fig. 5C). The brightest fluorescence was observed in the outer epidermal wall. This was quantified using TEM immunogold labeling and compared with labeling in mesophyll cell walls.

The distribution of JIM5, JIM7, 2F4 (which recognizes calcium ion-cross-linked HG), and CBM3a was determined using immunogold labeling in the outer cell walls of the epidermis (Figs. 4A and 5, B and D) and in mesophyll cell walls (Supplemental Table S1). Weak labeling was observed using the 2F4 antibody with a small but significant increase in the amount of gold labeling in both calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 cell walls (Fig. 4A). Immunogold labeling with JIM5 revealed that pectin epitopes are more abundant in the adaxial epidermal walls of calpain oe and reduced in amiRNA-DEK1 compared with the wild type (Fig. 5B). Immunogold labeling of wild-type adaxial epidermal walls with the JIM7 antibody showed an abundance of epitopes with an even distribution throughout the wall (Fig. 5D). HG epitopes recognized by JIM7 within the adaxial epidermal walls were present at similar levels in calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 leaves, although differences in their distribution were apparent (Fig. 5D). In calpain oe lines, epitopes recognized by JIM7 were observed both within and outside of the outer adaxial epidermal cell wall boundary, as if they spill out of the wall in this line (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. S5). In amiRNA-DEK1 lines, JIM7 labeling is seen bound to the outer surface of the outer epidermal cell wall in the region of the cuticle (Fig. 5D). This outside labeling does not occur in the wild type and is susceptible to pectinase treatment in calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1, indicating that this is specific labeling of pectin (Supplemental Fig. S6B). No major differences were observed in labeling by JIM5 and JIM7 in the mesophyll cell walls of calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 lines compared with the wild type (Supplemental Table S1), with the exception of JIM7 labeling in the palisade mesophyll cell walls in calpain oe leaves, for which a significant decrease was observed (Supplemental Table S1). Labeling of cellulose epitopes detected by CBM3a was increased in the periclinal epidermal cell walls of calpain oe leaves, yet no difference compared with the wild type was observed in mesophyll cell walls (Supplemental Table S1). In amiRNA-DEK1 leaves, a reduction in cellulose epitopes was observed in both epidermal and mesophyll cell walls (Fig. 4; Supplemental Table S1).

Similar changes in cell wall pectin epitope labeling/distribution were observed in the outer periclinal epidermal cell walls of both the adaxial and abaxial sides of leaves. This labeling pattern was recapitulated after demasking treatments, where sections were pretreated with a xyloglucanase and then labeled with JIM5 and JIM7 (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Demasking was performed to remove the possibility of cell wall epitope masking by the presence of another wall polymer, as has been reported previously (Marcus et al., 2008). In this study, we used arabinanase and xyloglucanase treatment to remove arabinan and xyloglucan, respectively. No change in labeling intensity was found after pretreatment using arabinanase. Xyloglucanase digestion revealed additional epitopes for JIM5 and JIM7 labeling in all three lines (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Differences in the distribution of other cell wall polysaccharides (cellulose/xylan/xyloglucan/arabinan/galactan/AGP) also were investigated in the outer periclinal cell walls of the adaxial epidermis using immunogold labeling of pectinase-treated samples to determine if pectin was further masking changes in these polymers (Supplemental Fig. S6). An increase in crystalline cellulose and xylan epitopes was seen in calpain oe plants after this treatment, although the inverse was not observed in amiRNA-DEK1 lines (Supplemental Fig. S6). This contrasts with the situation where no pretreatment was undertaken (Fig. 4). In amiRNA-DEK1, a significant decrease in galactan and xyloglucan epitopes was observed (Supplemental Fig. S6). These observations indicate that altered levels of DEK1 expression influence the spatial distribution of several cell wall components (Fig. 5).

The Expression of Several Cell Wall-Related Genes Is Correlated with DEK1 CALPAIN Transcript Levels

Several cell wall-related genes and other genes encoding proteins with putative cell wall-related signaling functions were shown to be highly up-regulated in a microarray study of calpain oe plants (Johnson et al., 2008). The expression of these genes was changed in lines constitutively overexpressing the active CALPAIN domain of DEK1; therefore, they represent likely downstream targets of DEK1 activity. In order to identify CALPAIN early-responsive genes, a dexamethasone (DEX)-inducible calpain oe line (ioex-calpain) was generated and used to investigate expression changes in liquid-grown seedlings. We used 10-d-old seedlings to capture transcriptional events that occur during early leaf development. CALPAIN transcript levels were compared between DEX- and control dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated seedlings (Fig. 6A). CALPAIN expression in DEX-treated plants increases as early as 2 h after induction and peaks at 8 h of treatment (20-fold increase with respect to DMSO-treated plants; Supplemental Table S2).

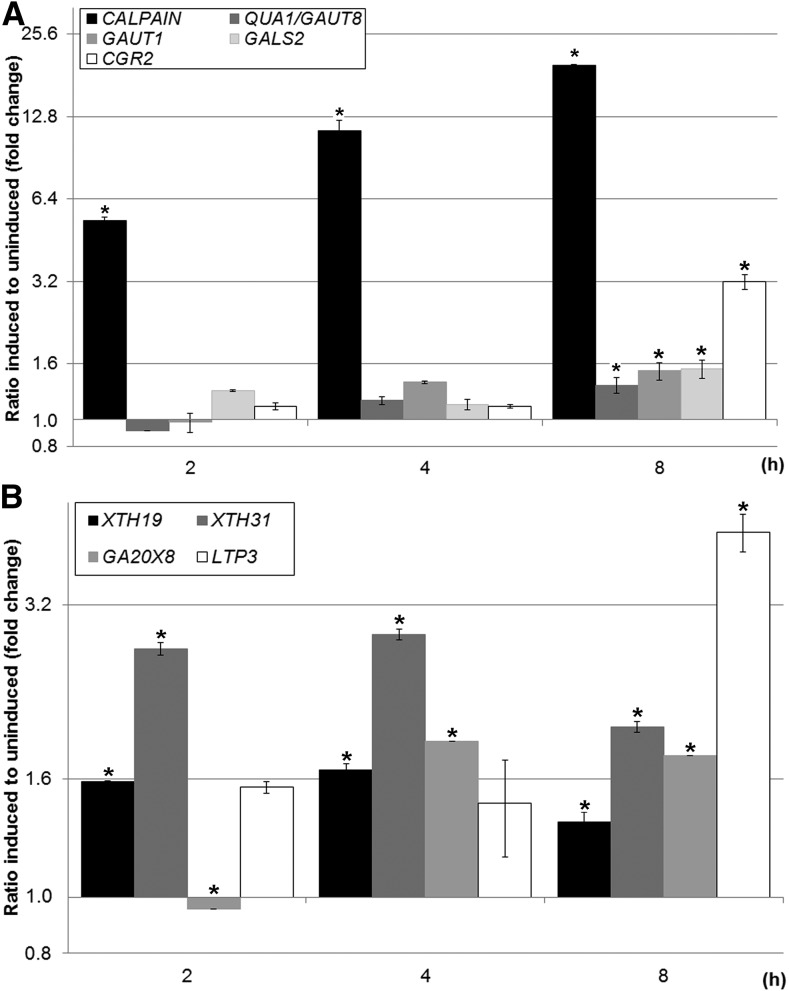

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of genes involved in cell wall and pectin biosynthesis and remodeling in ioex-calpain seedlings after treatment with DEX (induced) relative to the DMSO control (uninduced). A, Significant increases in the expression levels of XTH19, XTH31, and LTP3 were observed in ioex-calpain seedlings at 2, 4, and 8 h of DEX treatment, GA2OX8 after 4 and 8 h, and LTP2 after 2 h. B, Significant increases in the expression levels of QUA1/GAUT8, GALS2, and CGR2 were observed in ioex-calpain seedlings at 8 h of DEX treatment and GAUT1 after 4 and 8 h. CALPAIN expression levels were increased significantly after 2 h of induction. Asterisks indicate statistically significant values at P < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA. Error bars denote se.

As changes in the epitope labeling of cellulose, xyloglucan, and pectins were observed in calpain oe plants, we analyzed the expression of a specific subset of cell wall-related genes, including cellulose synthases (CESAs) and genes involved in pectin biosynthesis and xyloglucan metabolism. In addition, genes that showed up-regulation of more than 3-fold in microarray analysis of stable calpain oe lines (Johnson et al., 2008) were included in the analyses. Eleven genes were found to be up-regulated after 8 h of treatment with DEX: XYLOGLUCAN ENDOTRANSGLYCOSYLASE19 (XTH19), XTH31, LIPID TRANSFER PROTEIN3 (LTP3), GIBBERELLIN 2-OXIDASE8 (GA2OX8), GALACTAN SYNTHASE2 (GALS2), ERF/AP2 TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR, COTTON GOLGI-RELATED2 (CGR2), QUASIMODO1 (QUA1)/HG:GALACTURONOSYL-TRANSFERASE8 (GAUT8) and GAUT1, GPI-ANCHORED LIPID PROTEIN TRANSFER2, and PROTODERMAL FACTOR2 (PDF2; Supplemental Table S2). No change in the expression of CESAs involved in cellulose synthesis in primary cell walls was observed (Supplemental Table S2).

To investigate the link between increased pectin content in calpain oe walls and pectin biosynthesis, the expression levels of pectin biosynthetic genes was determined in ioex-calpain lines at earlier time points. We determined the expression of GAUT8 and GAUT1, encoding putative membrane-bound glycosyltransferases, GALS2, encoding an enzyme involved in pectic galactan biosynthesis, and CGR2 and CGR3, encoding enzymes involved in pectin methylesterification. None of these genes showed significant differences in expression until 8 h after DEX treatment (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Table S2). In addition, PECTIN METHYLESTERASE35 (PME35) and an ERF/AP2 TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR, proposed to regulate pectin biosynthesis genes (Nakano et al., 2012), were transiently down-regulated after 4 h of induction (Supplemental Table S2).

Of the genes that showed up-regulation in the microarray analysis of stable calpain oe lines, three genes showed an expression trend that correlates with CALPAIN levels (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Table S2). XTH19 and XTH31, encoding enzymes that stitch together xyloglucan chains, are significantly up-regulated after 2, 4, and 8 h induction (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Table S2). In addition, GA2OX8, encoding an enzyme predicted to inactivate GAs by β-hydroxylation of GA precursors (Schomburg et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2005), showed a greater than 2-fold increase after both 4 and 8 h of induction (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Table S2). LTP3, encoding a protein involved in lipid binding, germination, and abiotic stress responses (Carvalho and Gomes, 2007; Guo et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Pagnussat et al., 2015), was up-regulated after 8 h (Fig. 6B). These observations suggest that a subset of cell wall-related genes are involved in early downstream responses to DEK1 and that other responses are likely later responses to changes in the level of DEK1 CALPAIN.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence for a role of DEK1 in regulating cell wall thickness and composition and proposes a role for DEK1 in ensuring the integrity and coordination of cell wall biogenesis in the epidermis during growth (Fig. 7). The primary cell wall has a crucial function during growth in allowing expansion while maintaining structural integrity and does so by a complex and orchestrated process that relies on modulating the physicochemical properties of a biomaterial that consists of a network of cellulose microfibrils embedded in a hydrated gel-like phase of noncellulosic and pectic polysaccharides and some proteins. The rigid cellulose microfibrils influence the direction of growth and the noncellulosic polysaccharides, such as xyloglucans, and the pectins and structural proteins provide the matrix in which cellulose is laid down (Doblin et al., 2010; Cosgrove, 2014). A key function of the cell wall is to permit cells to generate turgor pressure required for growth, and sensing the status of the wall to enable regulated loosening and reinforcement, both global and local, in the face of this pressure is crucial.

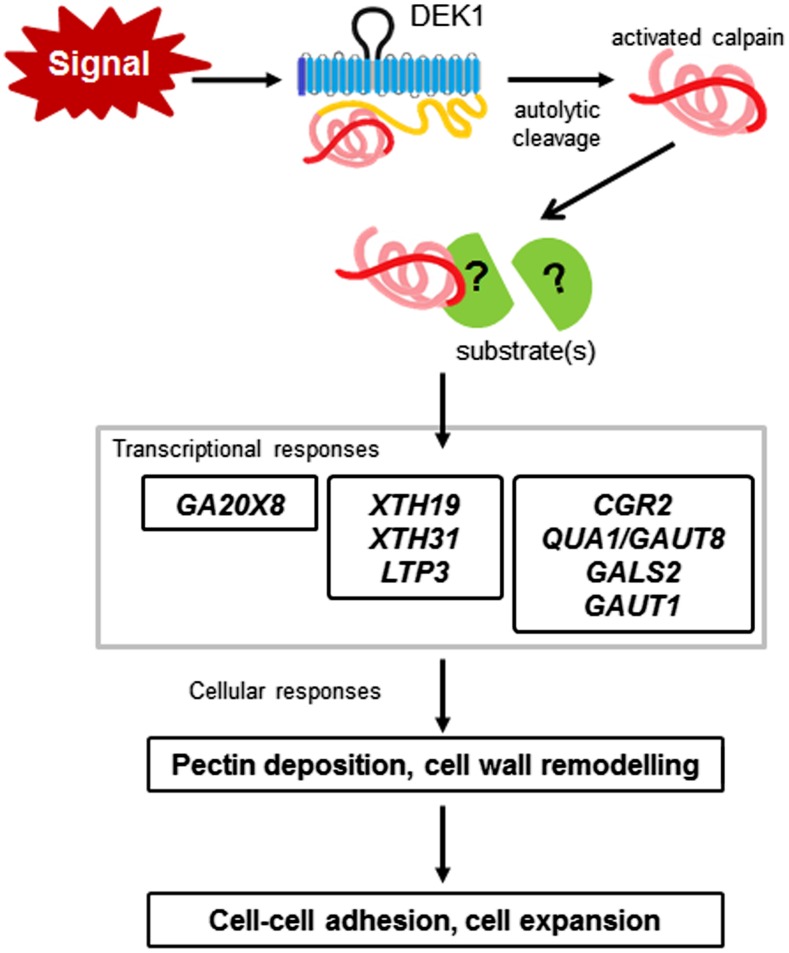

Figure 7.

Model explaining the DEK1 pathway regulating cell wall composition. DEK1 is proposed to respond to an external signal that initiates autolytic cleavage of the CALPAIN domain. The CALPAIN domain cleaves unknown, likely cytoplasmic, target proteins that act in signaling pathways to promote the expression of cell wall-related genes, including LTPs, XTHs, CGR2, GAUTs, and GALS2, as well as GA2OX8. Proteins encoded by these genes act to remodel the cell wall, for example, acting on xyloglucans and pectins. This leads to maintenance of the integrity of the cell wall, adhesion between cells, and regulated cell expansion.

As a protein spanning the cell wall-plasma membrane-cytoplasm continuum, DEK1 is ideally located to respond to apoplastic signals (both physical and chemical) and regulate growth coordination through downstream signaling. Studies of DEK1 in the moss P. patens have led to the proposal that the extracellular loop within the TM domain of DEK1 (the MEM region) most likely acts as a sensor to detect stimuli from the external environment (Demko et al., 2014). Growth defects, including the development of aberrant gametophores lacking expanded phyllids, are seen in mutants expressing a PpDEK1 lacking the external loop. We propose a model whereby DEK1 detects an external signal that activates the autolytic cleavage of the calpain domain and initiates downstream signaling pathways (Fig. 7). This results in transcriptional responses to modify the expression of cell wall-related genes, the synthesis and deposition of wall polysaccharides/proteins, leading to the modification of cell wall composition and organization in the epidermis, and promotes cell-cell adhesion and cell expansion (Fig. 7).

One possibility is that DEK1 could act in concert with other membrane-localized cell wall modifiers such as receptor-like kinases involved in cell wall integrity sensing. Candidates include the Catharanthus roseus receptor-like kinases FERONIA, THESEUS1, and HERCULES1, thought to detect changes in pectin (Guo et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2012a); the R5-LIKE RECEPTOR KINASE/THAUMATIN family and the LysM family (Trudel et al., 1998; Miya et al., 2007; Bai et al., 2009; Wolf et al., 2012a); wall-associated kinases (WAKs) and WAK-like kinases (Anderson et al., 2001; Decreux and Messiaen, 2005; Wolf et al., 2012a); and the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 (Wolf et al., 2012b, 2014). These proteins are proposed to sense alterations/defects in the wall and trigger signaling pathways to promote the production/activity of cell wall remodeling and synthesis enzymes, thus maintaining wall integrity during growth and in response to pathogens (Monshausen and Gilroy, 2009; Wolf et al., 2012a).

Our work shows that DEK1 activity controls cell wall thickness and composition and, consequently, cell shape in the epidermis. Cell walls in the epidermis have been shown to play an important role in the regulation of cell shape and size (for review, see Ivakov and Persson, 2013). Several studies using weak dek1 alleles have identified a role for DEK1 as a key regulator in the maintenance and differentiation of the epidermal layer (Roeder et al., 2012; Galletti et al., 2015). DEK1 has been shown to regulate the expression of the HD-ZIP family IV transcription factors (ATML1, PDF2, HDG11, HDG12, and HDG2) involved in epidermis specification and differentiation. Interestingly, the epidermis-specific HD ZIP transcription factor HDG11, the expression of which is reduced in plants with reduced DEK1 activity (Galletti et al., 2015), has been shown to directly promote cell wall-loosening genes in roots (Xu et al., 2014). Determining whether the epidermis-specific HD ZIP transcription factors acting downstream of DEK1 regulate the expression of cell wall genes may further clarify the pathways through which DEK1 acts.

We have shown that cell walls in the epidermis of calpain oe and amiRNA-DEK1 plants have altered cell wall composition (Fig. 4), and this is likely to be due to changes in the regulation of genes encoding enzymes involved in the assembly and/or modification of cell wall polymers. We observed significant increases in the expression of genes involved in pectin biosynthesis and remodeling, including GALS2, QUA1/GAUT8, GAUT1, and CGR2 (Fig. 6). These genes are important for normal pectin biosynthesis and plant growth, as decreased pectin levels and cell adhesion defects are observed in qua1 mutants (Bouton et al., 2002; Leboeuf et al., 2005) and gaut mutants are lethal (Caffall et al., 2009). CGR2 encodes an enzyme proposed to add methylesters to partially and/or nonesterified pectin backbones, resulting in more highly methylesterified pectin (Kim et al., 2015). We observed increased levels of pectins in the cell walls of the epidermis in calpain oe plants, consistent with the up-regulation of these genes.

In addition to pectins, xyloglucans are the other major noncellulosic polysaccharide in the primary walls proposed to interact with cellulose and play a role as a load-bearing network. Recent NMR studies show that, rather than xyloglucan, pectins make the majority of contacts with cellulose and might serve as mechanical tethers between cellulose microfibrils (Wang et al., 2012). Rather than a tethering role, the role of xyloglucan is thought to be restricted to biomechanical hotspots where xyloglucan interacts with cellulose microfibrils (Park and Cosgrove, 2012; Cosgrove, 2014). We observed the up-regulation of genes encoding wall-bound XTHs in response to increased CALPAIN levels (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Table S2). XTHs act as creep-promoting agents by stitching together load-bearing xyloglucan chains to non-load-bearing xyloglucan chains to promote the extensibility of cell walls (Fry et al., 1992; Takeda et al., 2002; Whitney et al., 2006; Wolf et al., 2012a). The increased expression of XTHs in calpain oe plants likely contributes to the increased cell expansion observed in these lines (Fig. 2).

A reduction of cellulose, pectin, and xyloglucan in amiRNA-DEK1 epidermal cells could influence the organization of cellulose in the cell wall, the adhesion between cells, and the integrity of cell walls, resulting in cell separation and the reduced cell-cell contacts observed in these lines (Fig. 3; Supplemental Fig. S3; Galletti et al., 2015). Smaller rosette leaves are observed in amiRNA-DEK1, and one explanation could be that the reduced cell-cell contacts and thinner walls in epidermal cells of amiRNA-DEK1 lines result in cell wall integrity defects during expansion and, therefore, limit the capacity for growth. This is supported by kinematic analysis showing that the growth rate in amiRNA-DEK1 plants slows down earlier than in wild-type plants.

In young leaves of calpain oe plants, an increase in both high- and low-DE HG is observed, with the more soluble pectins detected by JIM7 seeming to spill out of the wall onto the leaf surface. The degree and pattern of pectin methylesterification plays a critical role in maintaining the elasticity, permeability, porosity, cell adhesion, and compressibility of cell walls during growth and development (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993; Wolf et al., 2009; Peaucelle et al., 2012). Low-DE HG often is associated with reduced extensibility due to the capacity for Ca2+ cross-linking, whereas the more soluble high-DE HG commonly occurs in regions of growth where cells are undergoing cell wall extension (Boyer, 2009). However, this correlation does not always hold true; for example, pectin demethylesterification in the shoot apical meristem (Peaucelle et al., 2011) and hypocotyl (Peaucelle et al., 2015) of Arabidopsis has been shown to have a cell wall-loosening effect. This is likely due to the complex relationships between PMEs, PMEIs, and HG-degrading enzymes and the dynamics of synthesis and turnover. The composition of pectins also may differ depending on the cellular context, for example in the shoot apical meristem (Yang et al., 2016).

Our results are consistent with increased levels of low-DE HG (recognized by JIM5) cross-linking in the outer walls of the epidermis and resulting in limited cell expansion during early leaf development. At later stages of leaf development, the levels of high-DE HG are increased compared with the wild type, and this may enable cell expansion to continue for longer (Fig. 4). The extended expansion phase also could be linked to the fact that cell walls are thicker and cellular integrity can be maintained for longer (Figs. 2B and 3E).

It is interesting that the cell wall thickness of internal leaf cells, such as those of the mesophyll, were not altered in either calpain oe or amiRNA-DEK1 plants (Table I). The composition of pectins and cellulose also was largely unchanged in these cell types (Supplemental Table S1). A reduction in the labeling of cellulose epitopes was observed in mesophyll cell walls of amiRNA-DEK1 plants, although no difference in cellulose content was detected (Supplemental Fig. S4). Nonetheless, it is possible that other polymers, such as pectins, mask the cellulose epitopes, as seems to occur in the epidermis (Supplemental Fig. S6), and this requires further investigation. Thus, although DEK1 is expressed in all cell types, it seems to be particularly important in the epidermis (Becraft et al., 2002; Roeder et al., 2012; Galletti et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2015). This is consistent with the proposed role of DEK1 in growth coordination and the importance of the epidermis for this function (Savaldi-Goldstein et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008; Hacham et al., 2011).

CONCLUSION

We propose that DEK1 plays an important role in the coordination of organ morphogenesis by regulating the transcription of genes involved in the deposition and remodeling of cell wall components in the epidermis. We show that DEK1 affects HG biosynthesis and alters the ratio between low- and high-DE HG, potentially contributing to altering cell wall expansion. Together, these changes may contribute to the observed alterations in cell morphology that underlie the phenotypic changes observed in DEK1-modulated lines. In the future, identification of the immediate substrates of DEK1 will be of key importance to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia wild-type, calpain oe (Johnson et al., 2008), and amiRNA-DEK1 (Galletti et al., 2015) plants were grown in a growth chamber (Thermoline) under short-day conditions with an 8-h-light/16-h-dark cycle at 21°C for 12 weeks.

For nondestructive analysis of vegetative growth (see below), plants were grown in a Reach-in Multifunctional growth chamber (Adaptis A1000; Conviron) with a photosynthetic photon fluence rate of 190 ± 30 μmol m−2 s−1 (over the waveband 400–700 nm).

Phenotypic Characterization of Vegetative Growth

Nondestructive analysis of vegetative growth was provided by the Plant Phenomics facility in Canberra, Australia (http://www.plantphenomics.org.au/services/model/). Seeds were sown directly in a row-column design layout over three trays and grown in 68-mm-tube square pots, within 10-cell Kwikpot Trays, in Hydro Grass trays. Plants were removed from the Conviron Adaptis growth chamber every day for imaging. Trays were photographed individually in the Scanalyser3D growth imaging system (Lemnatec) after being manually loaded into it. For each imaging session, images were captured during a specific time window each day (3 h after the onset of daylight ± 30 min). The images were captured in an eight-bit RGB mode with a spatial resolution of 2,454 × 2,056 pixels, giving a true physical resolution of 42.4 pixels mm−2. Collected images were analyzed using a Lemnatec proprietary computer vision library provided with the image-capturing system.

Kinematic Analysis of Leaf Growth and Rosette Leaf Shape

The protocol for measuring the epidermal leaf imprint was adapted from Breuninger and Lenhard (2010) and was performed on the abaxial side of sixth rosette leaves every 3 d with six biological replicates. The leaf imprints were observed with both the Leica M205A dissecting microscope (Leica Microsystems) for leaf area analysis and the Leica DM 2500 compound microscope at 20× magnification for cell size and numbers (kinematic) analysis. Images were captured and then analyzed using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Kinematic analysis was carried out by counting the average cell number in a 2,016- × 2,016-pixel plot area in the middle part of the leaf lamina. Six biological replicates were measured for each line at each time point. The average cell size was determined by dividing plot area by cell number. The total number of cells per leaf was determined by dividing the leaf area by the average cell area, following the protocol of De Veylder et al. (2001).

Fixation and Embedding of Plant Material

The fixation protocol for Arabidopsis tissue was adapted from Wilson and Bacic (2012). Tissue was fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in potassium phosphate buffer (0.025 m PBS, pH 7) and then embedded in 100% LR White resin. Thin sections (90 and 250 nm) were obtained with a Leica Ultracut R microtome and placed on formvar-coated 100-mesh gold grids (Proscitech) for TEM study and on glass microscope slides for fluorescence immunolocalization experiments, respectively.

Antibodies and Demasking

Antibodies were used to recognize the following cell wall epitopes. For HG, JIM5 and JIM7 (Knox et al., 1990) were from PlantProbes. For fluorescence microscopy, either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich; no. F1763) or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L; Life Technologies; no. A11001) was used as the secondary antibody. For TEM studies, 18-nm colloidal gold-conjugated goat anti-rat or anti-mouse IgG (both Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used. The method for epitope demasking was modified from Wilson et al. (2015). Samples were pretreated with 2 m urea in PBS for 30 min at room temperature before incubation in polysaccharide-specific hydrolases. Pectinase (1 unit mL−1; Sigma-Aldrich; no. P-2410), arabinanase (1 unit mL−1; Megazyme; E-ARBACJ), and xyloglucanase (1 unit mL−1; Megazyme; E-XEGP) digestions were conducted in PBS containing 2 m urea and 0.1% Tween 20 for 4.5 h at room temperature, subsequently washed six times with 2 m urea with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, and then three times with PBS. To assess the specificity of the labeling, several controls were done by preadsorbing JIM5 with pectin DE 30% substrate (1 mg mL−1; CP Kelco Aps) and JIM7 with pectin DE 60% substrate (1 mg mL−1; Herbstreith & Fox; no. 01401094) overnight.

Confocal Laser-Scanning Microscopy Analysis

Fluorescence immunolocalization experiments were carried out following the protocol from Coimbra et al. (2007), and imaging was performed on a Leica SP5 microscope using laser beam lines of 405 nm (Calcofluor White) and 488 nm (FITC and Alexa Fluor 488). Emitted fluorescence was captured between 415 and 455 nm for Calcofluor White and between 500 and 550 nm for FITC and Alexa Fluor 488. Images were analyzed with Zeiss Zen software and Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012). Images were processed with Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012).

TEM

The protocol for the preparation of plant cells for TEM was adapted from Wilson and Bacic (2012). The grids were viewed using an FEI Tecnai Spirit transmission electron microscope equipped with a Gatan CCD camera. Image analysis was performed with ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) to measure cell wall thickness, gold density, and cell-cell junctions.

Induction of DEX-Inducible Calpain Lines

The ioex-calpain line was generated by amplifying the CALPAIN domain by PCR as outlined by Johnson et al. (2008). CALPAIN was recombined into pDONR221 (Invitrogen) and then into the pOPON2.1 vector (a gift from Ian Moore, University of Oxford). Arabidopsis wild-type and ioex-calpain seeds were sterilized and grown in Murashige and Skoog (MS) liquid medium in 90- × 25-mm plastic petri dishes at 21°C and 100 rpm for 10 d in three biological replicates. Induction was started by transferring half the seedlings into MS liquid medium containing 10 µm DEX in DMSO (Xie et al., 2000; Günl et al., 2009; Serrano et al., 2010) and the remaining seedlings into MS medium with DMSO (without DEX) as a control.

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR was used to measure the expression level of 10 cell wall-related genes (PMEIs, XTHs, LTPs, ATPI4Ky3, ERF/AP2 TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR, and GA2OX8) identified from microarray experiments (Johnson et al., 2008), a gene involved in epidermal differentiation (PDF2; Abe et al., 2003), pectin biosynthetic genes (GALSs, GAUTs, QUAs, PME35, and CGRs), and CESA genes (Supplemental Table S1). RNA from DMSO- and DEX-treated seedlings across time points was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen; no. 18080-044). Expression levels of each gene were assessed using an absolute quantitative method with a standard curve (Burton et al., 2004), and the transcript levels were then normalized against three housekeeping genes, TUBULIN, CYCLOPHYLIN, and ACTIN (Burton et al., 2004). The standards with known copy number (to make the standard curve) were obtained following the protocol from Burton et al. (2004). The RT-qPCR experiments were carried out from two independent induction experiments with two biological replicates and three technical replicates in the Bio-Rad CFX384 Real-Time System using KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit Master Mix (2X) Universal (Kapa Biosystems; no. KK4601) in 10-µL reactions, and the reactions were performed as follows: 3 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 3 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, 20 s at 72°C, and 15 s at the optimal acquisition temperature. The products were validated by sequencing. The melt curve was obtained from the product by heating from 72°C to 95°C. Statistics were performed comparing the ratio of DEX-treated and DMSO-treated samples between biological repeats.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Projected leaf and epidermal cell area over time in calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S2. Epidermis cell size distribution over time in leaf 6 of calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S3. Epidermis cell-cell contact zones of adaxial and abaxial faces from leaf 4 of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S4. Analysis of cell wall monosaccharide and polysaccharide composition from the four youngest leaves of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S5. Demasking study using xyloglucanase pretreatment prior to the application of pectin antibodies in cross sections derived from leaf 4 of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Figure S6. TEM immunogold labeling of cell wall epitopes after premasking treatment with pectinase in TEM transverse sections of periclinal epidermal walls from leaf 4 of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Table S1. Measurement of the immunogold density of cell wall epitopes in TEM transverse sections of palisade and spongy mesophyll walls from leaf 4 of 17-d-old calpain oe, wild-type, and amiRNA-DEK1 plants.

Supplemental Table S2. RT-qPCR analysis of the expression levels of selected genes in ioex-calpain seedlings after treatment with DEX relative to the DMSO control.

Supplemental Table S3. List of primers.

Supplemental Table S4. Calculation of polysaccharide composition based on linkage analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members from our research group for excellent support, especially Dr. John Humphries for valuable feedback, Roshan Cheetamun for technical assistance in carbohydrate assays, and Dr. Edwin Lampugnani for providing the pYidong cloning vector; as well as Dr. Neil Shirley from the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Plant Cell Walls, University of Adelaide, for providing RT-qPCR standards.

Glossary

- TM

transmembrane

- HG

homogalacturonan

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- DEX

dexamethasone

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Plant Cell Walls (grant no. CE1101007), a Melbourne Research Scholarship (MIRS and MIFRS to D.A.), and the Albert Shimmins Fund from the University of Melbourne.

References

- Abe M, Katsumata H, Komeda Y, Takahashi T (2003) Regulation of shoot epidermal cell differentiation by a pair of homeodomain proteins in Arabidopsis. Development 130: 635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JW, Kim M, Lim JH, Kim GT, Pai HS (2004) Phytocalpain controls the proliferation and differentiation fates of cells in plant organ development. Plant J 38: 969–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, Wagner TA, Perret M, He ZH, He D, Kohorn BD (2001) WAKs: cell wall-associated kinases linking the cytoplasm to the extracellular matrix. Plant Mol Biol 47: 197–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Zhang G, Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Wang W, Du Y, Wu Z, Song CP (2009) Plasma membrane-associated proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinase 4, a novel regulator of Ca signalling, is required for abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 60: 314–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled M, Urbanowicz BR, O’Neill MA (2012) The synthesis and origin of the pectic polysaccharide rhamnogalacturonan II: insights from nucleotide sugar formation and diversity. Front Plant Sci 3: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becraft PW, Li K, Dey N, Asuncion-Crabb Y (2002) The maize dek1 gene functions in embryonic pattern formation and cell fate specification. Development 129: 5217–5225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton S, Leboeuf E, Mouille G, Leydecker MT, Talbotec J, Granier F, Lahaye M, Höfte H, Truong HN (2002) QUASIMODO1 encodes a putative membrane-bound glycosyltransferase required for normal pectin synthesis and cell adhesion in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 2577–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JS. (2009) Evans Review. Cell wall biosynthesis and the molecular mechanism of plant enlargement. Funct Plant Biol 36: 383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuninger H, Lenhard M (2010) Control of tissue and organ growth in plants. Curr Top Dev Biol 91: 185–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RA, Shirley NJ, King BJ, Harvey AJ, Fincher GB (2004) The CesA gene family of barley: quantitative analysis of transcripts reveals two groups of co-expressed genes. Plant Physiol 134: 224–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffall KH, Mohnen D (2009) The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydr Res 344: 1879–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffall KH, Pattathil S, Phillips SE, Hahn MG, Mohnen D (2009) Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutants implicate GAUT genes in the biosynthesis of pectin and xylan in cell walls and seed testa. Mol Plant 2: 1000–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM (1993) Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J 3: 1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AO, Gomes VM (2007) Role of plant lipid transfer proteins in plant cell physiology: a concise review. Peptides 28: 1144–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catoire L, Pierron M, Morvan C, du Penhoat CH, Goldberg R (1998) Investigation of the action patterns of pectinmethylesterase isoforms through kinetic analyses and NMR spectroscopy: implications in cell wall expansion. J Biol Chem 273: 33150–33156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra S, Almeida J, Junqueira V, Costa ML, Pereira LG (2007) Arabinogalactan proteins as molecular markers in Arabidopsis thaliana sexual reproduction. J Exp Bot 58: 4027–4035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. (1999) Enzymes and other agents that enhance cell wall extensibility. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 391–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. (2005) Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 850–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. (2014) Re-constructing our models of cellulose and primary cell wall assembly. Curr Opin Plant Biol 22: 122–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croall DE, Ersfeld K (2007) The calpains: modular designs and functional diversity. Genome Biol 8: 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreux A, Messiaen J (2005) Wall-associated kinase WAK1 interacts with cell wall pectins in a calcium-induced conformation. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 268–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demko V, Perroud PF, Johansen W, Delwiche CF, Cooper ED, Remme P, Ako AE, Kugler KG, Mayer KFX, Quatrano R, et al. (2014) Genetic analysis of DEFECTIVE KERNEL1 loop function in three-dimensional body patterning in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Physiol 166: 903–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire P, Findlay K, McCann MC, Roberts K (2007) Cell elongation in Arabidopsis hypocotyls involves dynamic changes in cell wall thickness. J Exp Bot 58: 2079–2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veylder L, Beeckman T, Beemster GT, Krols L, Terras F, Landrieu I, van der Schueren E, Maes S, Naudts M, Inzé D (2001) Functional analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13: 1653–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo A, Giovane A, Raiola A, Camardella L, Bonivento D, De Lorenzo G, Cervone F, Bellincampi D, Tsernoglou D (2005) Structural basis for the interaction between pectin methylesterase and a specific inhibitor protein. Plant Cell 17: 849–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doblin MS, Pettolino F, Bacic A (2010) Evans Review. Plant cell walls: the skeleton of the plant world. Funct Plant Biol 37: 357–381 [Google Scholar]

- Driouich A, Follet-Gueye ML, Bernard S, Kousar S, Chevalier L, Vicré-Gibouin M, Lerouxel O (2012) Golgi-mediated synthesis and secretion of matrix polysaccharides of the primary cell wall of higher plants. Front Plant Sci 3: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S, Savatin DV, Sicilia F, Gramegna G, Cervone F, Lorenzo GD (2013) Oligogalacturonides: plant damage-associated molecular patterns and regulators of growth and development. Front Plant Sci 4: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AJ, McQueen-Mason S, Mandel T, Kuhlemeier C (1997) Induction of leaf primordia by the cell wall protein expansin. Science 276: 1415–1418 [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC, Smith RC, Renwick KF, Martin DJ, Hodge SK, Matthews KJ (1992) Xyloglucan endotransglycosylase, a new wall-loosening enzyme activity from plants. Biochem J 282: 821–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletti R, De Lorenzo G, Ferrari S (2009) Host-derived signals activate plant innate immunity. Plant Signal Behav 4: 33–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletti R, Ferrari S, De Lorenzo G (2011) Arabidopsis MPK3 and MPK6 play different roles in basal and oligogalacturonide- or flagellin-induced resistance against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 157: 804–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletti R, Johnson KL, Scofield S, San-Bento R, Watt AM, Murray JAH, Ingram GC (2015) DEFECTIVE KERNEL 1 promotes and maintains plant epidermal differentiation. Development 142: 1978–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Díaz BE, Gauthier S, Davies PL (2006) Ca2+ dependency of calpain 3 (p94) activation. Biochemistry 45: 3714–3722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovane A, Servillo L, Balestrieri C, Raiola A, D’Avino R, Tamburrini M, Ciardiello MA, Camardella L (2004) Pectin methylesterase inhibitor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1696: 245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl M, Liew EF, David K, Putterill J (2009) Analysis of a post-translational steroid induction system for GIGANTEA in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol 9: 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Ye H, Li L, Yin Y (2009) A family of receptor-like kinases are regulated by BES1 and involved in plant growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav 4: 784–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Yang H, Zhang X, Yang S (2013) Lipid transfer protein 3 as a target of MYB96 mediates freezing and drought stress in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 64: 1755–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacham Y, Holland N, Butterfield C, Ubeda-Tomas S, Bennett MJ, Chory J, Savaldi-Goldstein S (2011) Brassinosteroid perception in the epidermis controls root meristem size. Development 138: 839–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt J, Suttangkakul A, Scheller HV (2010) Biosynthesis of pectin. Plant Physiol 153: 384–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivakov A, Persson S (2013) Plant cell shape: modulators and measurements. Front Plant Sci 4: 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KL, Degnan KA, Walker JR, Ingram GC (2005) AtDEK1 is essential for specification of embryonic epidermal cell fate. Plant J 44: 114–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KL, Faulkner C, Jeffree CE, Ingram GC (2008) The phytocalpain defective kernel 1 is a novel Arabidopsis growth regulator whose activity is regulated by proteolytic processing. Plant Cell 20: 2619–2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juge N. (2006) Plant protein inhibitors of cell wall degrading enzymes. Trends Plant Sci 11: 359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Held MA, Zemelis S, Wilkerson C, Brandizzi F (2015) CGR2 and CGR3 have critical overlapping roles in pectin methylesterification and plant growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 82: 208–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox JP, Linstead PJ, King J, Cooper C, Roberts K (1990) Pectin esterification is spatially regulated both within cell walls and between developing tissues of root apices. Planta 181: 512–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SB, Venkateswaran K, Kundu S (2010) Alternative conformational model of a seed protein DeK1 for better understanding of structure-function relationship. J Proteins Proteomics 1: 77–90 [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf E, Guillon F, Thoiron S, Lahaye M (2005) Biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of pectic polysaccharides in the cell walls of Arabidopsis mutant QUASIMODO 1 suspension-cultured cells: implications for cell adhesion. J Exp Bot 56: 3171–3182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Brown RC, Fletcher JC, Opsahl-Sorteberg HG (2015) CALPAIN-mediated positional information directs cell wall orientation to sustain plant stem cell activity, growth and development. Plant Cell Physiol 56: 1855–1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lid SE, Gruis D, Jung R, Lorentzen JA, Ananiev E, Chamberlin M, Niu X, Meeley R, Nichols S, Olsen OA (2002) The defective kernel 1 (dek1) gene required for aleurone cell development in the endosperm of maize grains encodes a membrane protein of the calpain gene superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 5460–5465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Zhang X, Lu C, Zeng X, Li Y, Fu D, Wu G (2015) Non-specific lipid transfer proteins in plants: presenting new advances and an integrated functional analysis. J Exp Bot 66: 5663–5681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SE, Verhertbruggen Y, Hervé C, Ordaz-Ortiz JJ, Farkas V, Pedersen HL, Willats WG, Knox JP (2008) Pectic homogalacturonan masks abundant sets of xyloglucan epitopes in plant cell walls. BMC Plant Biol 8: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margis R, Margis-Pinheiro M (2003) Phytocalpains: orthologous calcium-dependent cysteine proteinases. Trends Plant Sci 8: 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder K, Peña MJ, O’Neill MA, York WS (2012) Structural characterization of the heteroxylans from poplar and switchgrass. In Himmel EM, ed, Biomass Conversion: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 215–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann M, Rose J (2010) Blueprints for building plant cell walls. Plant Physiol 153: 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheli F. (2001) Pectin methylesterases: cell wall enzymes with important roles in plant physiology. Trends Plant Sci 6: 414–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miya A, Albert P, Shinya T, Desaki Y, Ichimura K, Shirasu K, Narusaka Y, Kawakami N, Kaku H, Shibuya N (2007) CERK1, a LysM receptor kinase, is essential for chitin elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19613–19618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen D. (2008) Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 266–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monshausen GB, Gilroy S (2009) Feeling green: mechanosensing in plants. Trends Cell Biol 19: 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustacas AM, Nari J, Borel M, Noat G, Ricard J (1991) Pectin methylesterase, metal ions and plant cell-wall extension: the role of metal ions in plant cell-wall extension. Biochem J 279: 351–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Naito Y, Kakegawa K, Ohtsuki N, Tsujimoto-Inui Y, Shinshi H, Suzuki K (2012) Increase in pectin deposition by overexpression of an ERF gene in cultured cells of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biotechnol Lett 34: 763–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Kay P, Wilson S, Swain SM (2009) ARABIDOPSIS DEHISCENCE ZONE POLYGALACTURONASE1 (ADPG1), ADPG2, and QUARTET2 are polygalacturonases required for cell separation during reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 216–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Sorimachi H (2012) Calpains: an elaborate proteolytic system. Biochim Biophys Acta 1824: 224–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnussat LA, Oyarburo N, Cimmino C, Pinedo ML, de la Canal L (2015) On the role of a lipid-transfer protein: Arabidopsis ltp3 mutant is compromised in germination and seedling growth. Plant Signal Behav 10: e1105417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YB, Cosgrove DJ (2012) A revised architecture of primary cell walls based on biomechanical changes induced by substrate-specific endoglucanases. Plant Physiol 158: 1933–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Braybrook S, Höfte H (2012) Cell wall mechanics and growth control in plants: the role of pectins revisited. Front Plant Sci 3: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Braybrook SA, Le Guillou L, Bron E, Kuhlemeier C, Höfte H (2011) Pectin-induced changes in cell wall mechanics underlie organ initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 21: 1720–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Louvet R, Johansen JN, Höfte H, Laufs P, Pelloux J, Mouille G (2008) Arabidopsis phyllotaxis is controlled by the methyl-esterification status of cell-wall pectins. Curr Biol 18: 1943–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A, Wightman R, Höfte H (2015) The control of growth symmetry breaking in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Curr Biol 25: 1746–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud PF, Demko V, Johansen W, Wilson RC, Olsen OA, Quatrano RS (2014) DEFECTIVE KERNEL1 (DEK1) is required for three-dimensional growth in Physcomitrella patens. New Phytol 203: 1943–1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley BL, O’Neill MA, Mohnen D (2001) Pectins: structure, biosynthesis, and oligogalacturonide-related signaling. Phytochemistry 57: 929–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder AHK, Cunha A, Ohno CK, Meyerowitz EM (2012) Cell cycle regulates cell type in the Arabidopsis sepal. Development 139: 4416–4427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaldi-Goldstein S, Peto C, Chory J (2007) The epidermis both drives and restricts plant shoot growth. Nature 446: 199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg FM, Bizzell CM, Lee DJ, Zeevaart JA, Amasino RM (2003) Overexpression of a novel class of gibberellin 2-oxidases decreases gibberellin levels and creates dwarf plants. Plant Cell 15: 151–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Hubert DA, Dangl JL, Schulze-Lefert P, Kombrink E (2010) A chemical screen for suppressors of the avrRpm1-RPM1-dependent hypersensitive cell death response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 231: 1013–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siklos M, BenAissa M, Thatcher GR (2015) Cysteine proteases as therapeutic targets: does selectivity matter? A systematic review of calpain and cathepsin inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B 5: 506–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T, Furuta Y, Awano T, Mizuno K, Mitsuishi Y, Hayashi T (2002) Suppression and acceleration of cell elongation by integration of xyloglucans in pea stem segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9055–9060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG, Rieu I, Steber CM (2005) Gibberellin metabolism and signaling. Vitam Horm 72: 289–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudel J, Grenier J, Potvin C, Asselin A (1998) Several thaumatin-like proteins bind to β-1,3-glucans. Plant Physiol 118: 1431–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin R, Cerclier C, Geneix N, Aguié-Béghin V, Gaillard C, Ralet MC, Cathala B (2010) Elaboration of extensin-pectin thin film model of primary plant cell wall. Langmuir 26: 9891–9898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Barry JK, Min Z, Tordsen G, Rao AG, Olsen OA (2003) The calpain domain of the maize DEK1 protein contains the conserved catalytic triad and functions as a cysteine proteinase. J Biol Chem 278: 34467–34474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Zabotina O, Hong M (2012) Pectin-cellulose interactions in the Arabidopsis primary cell wall from two-dimensional magic-angle-spinning solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry 51: 9846–9856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SE, Wilson E, Webster J, Bacic A, Reid JS, Gidley MJ (2006) Effects of structural variation in xyloglucan polymers on interactions with bacterial cellulose. Am J Bot 93: 1402–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Bacic A (2012) Preparation of plant cells for transmission electron microscopy to optimize immunogold labeling of carbohydrate and protein epitopes. Nat Protoc 7: 1716–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Ho YY, Lampugnani ER, Van de Meene AML, Bain MP, Bacic A, Doblin MS (2015) Determining the subcellular location of synthesis and assembly of the cell wall polysaccharide (1,3; 1,4)-β-d-glucan in grasses. Plant Cell 27: 754–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Hématy K, Höfte H (2012a) Growth control and cell wall signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 63: 381–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Mouille G, Pelloux J (2009) Homogalacturonan methyl-esterification and plant development. Mol Plant 2: 851–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Mravec J, Greiner S, Mouille G, Höfte H (2012b) Plant cell wall homeostasis is mediated by brassinosteroid feedback signaling. Curr Biol 22: 1732–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, van der Does D, Ladwig F, Sticht C, Kolbeck A, Schürholz AK, Augustin S, Keinath N, Rausch T, Greiner S, et al. (2014) A receptor-like protein mediates the response to pectin modification by activating brassinosteroid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 15261–15266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Frugis G, Colgan D, Chua NH (2000) Arabidopsis NAC1 transduces auxin signal downstream of TIR1 to promote lateral root development. Genes Dev 14: 3024–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Cai XT, Wang Y, Xing L, Chen Q, Xiang CB (2014) HDG11 upregulates cell-wall-loosening protein genes to promote root elongation in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 65: 4285–4295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Schuster C, Beahan CT, Charoensawan V, Peaucelle A, Bacic A, Doblin MS, Wightman R, Meyerowitz EM (2016) Regulation of meristem morphogenesis by cell wall synthases in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 26: 1404–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.