Abstract

The two evolutionarily conserved mammalian lipid kinases Vps34 and PIKfyve are involved in an important physiological relationship, whereby the former produces phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) 3P that is used as a substrate for PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis by the latter. Reduced production of PtdIns(3,5)P2 in proliferating mammalian cells is phenotypically manifested by the formation of multiple translucent cytoplasmic vacuoles, readily rescued upon exogenous delivery of PtdIns(3,5)P2 or overproduction of PIKfyve. Although the aberrant vacuolation phenomenon has been frequently used as a sensitive functional measure of localized PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction, cellular factors governing the appearance of cytoplasmic vacuoles under PtdIns3P-PtdIns(3,5)P2 loss remain elusive. To gain further mechanistic insight about the vacuolation process following PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction, in this study we sought for cellular mechanisms required for manifestation of the aberrant endomembrane vacuoles triggered by PIKfyve or Vps34 dysfunction. The latter was achieved by various means such as pharmacological inhibition, gene disruption, or dominant-interference in several proliferating mammalian cell types. We report here that inhibition of V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 as well as inactivation of the GTP-GDP cycle of Rab5a GTPase phenotypically rescued or completely precluded the cytoplasmic vacuolization despite the continued presence of inactivated PIKfyve or Vps34. Bafilomycin A1 also restored the aberrant EEA1-positive endosomes, enlarged upon short PIKfyve inhibition with YM201636. Together, our work identifies for the first time that factors such as active V-ATPase or functional Rab5a cycle are acting coincidentally with the PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction in triggering formation of aberrant cytoplasmic vacuoles under PIKfyve or Vps34 dysfunction.

Keywords: cytoplasmic vacuolation, vacuolar H+ ATPase, bafilomycin A1, Rab5a GTPase, PIKfyve inactivation, Vps34 inactivation, YM201636, wortmannin, chloroquine, NH4Cl

the mammalian endosomal system is a complex dynamic network of vesicular and tubular membrane structures, which performs vital sorting and transporting events. Two types of endosomes are distinguished: early and late. Early endosomes continuously provide late endosomes with cargo destined for lysosomal degradation as well as with characteristic membrane proteins via processes of endosome carrier vesicle (ECV) budding/detachment and/or multivesicular body (MVB) maturation, which are essential steps in late endosome/lysosome biogenesis and function (2, 16, 21, 54). The phosphoinositide kinase PIKfyve, a sole and evolutionarily conserved mammalian enzyme, synthesizing PtdIns(3,5)P2 (phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate) and PtdIns5P (59), emerged as a critical regulator of the endosome maturation process (21, 51). Data from endosome reconstitution assays, revealing enhanced fission (or maturation) of transport intermediates from early endosomes under conditions enhancing production of PIKfyve lipid products, support this notion (51, 56).

One of the best known consequences associated with PIKfyve dysfunction in mitotic, but not terminally differentiated, cells is massive and progressively exacerbating cytoplasmic vacuolization, first observed by expression of the dominant-negative kinase-deficient PIKfyveK1831E mutant in COS cells (30). The endomembrane defects due to PIKfyveK1831E expression commence with early endosome dilation and culminate with the formation of numerous translucent autophagosome-distinct vacuoles that appear first at the perinuclear region prior to occupying the entire cell (29, 30, 55). Subsequent studies in various proliferating cell types with inactivated PIKfyve achieved by various means, such as siRNA-mediated depletion (10, 49), genetic disruption (24, 31, 42, 61, 64) and pharmacological inhibition by the PIKfyve specific inhibitor YM201636 or related compounds (6, 10, 36, 50), have all invariantly demonstrated the formation of translucent cytoplasmic vacuoles whose number and size are dependent on the dose and duration of the treatment. Whereas PIKfyve makes two lipid products by direct biosynthesis—both of which are reduced under all of the above perturbation experiments (59)—the vacuolation phenomenon is attributed to the selective loss of PtdIns(3,5)P2. Thus, aberrant vacuolation is triggered only by PIKfyve mutants deficient for PtdIns(3,5)P2, but not PtdIns5P synthesis, and is rescued by exogenous delivery of PtdIns(3,5)P2 but not PtdIns5P, as shown in COS cells (26, 58). Likewise, aberrant vacuoles do not form under selective pharmacological inhibition of PIKfyve-catalyzed PtdIns5P synthesis in mitotic cells (50).

Our recent quantitative analyses of phosphoinositides in cells with gene deficiency of evolutionarily conserved Vps34, the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PIK3C3), have revealed that Vps34 is a main supplier of the PtdIns3P precursor for PIKfyve-catalyzed constitutive PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis (31). Similarly to PIKfyve dysfunction, Vps34 perturbation by siRNA silencing, inhibitory antibodies, gene disruption or pharmacological inhibition also causes massive cytoplasmic vacuolation (1, 12, 14, 34, 37, 44). Our observation that exogenous Vps34 could restore the aberrant vacuolation in Vps34 deficient cells, but only in the presence of active PIKfyve, substantiates the conclusion that disrupted endomembrane homeostasis under Vps34 dysfunction is due to ablation of Vps34-produced PtdIns3P and depletion of the PtdIns3P pool needed downstream for PIKfyve-catalyzed PtdIns(3,5)P2 production (31). Although the vacuolation phenomenon has been frequently used as a sensitive functional measure of localized PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction, factors and mechanisms governing the cytoplasmic vacuoles triggered by PtdIns3P-PtdIns(3,5)P2 loss remain elusive.

In addition to direct perturbation of the Vps34-PIKfyve signaling axis, cytoplasmic vacuolation has long been known to be triggered under other conditions, including cell treatment with weak bases and intoxication with the Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin (5, 9, 18). Remarkably, in both these cases, a link with the PIKfyve/PtdIns(3,5)P2 pathway has emerged by the observations that ∼50% elevation of PtdIns(3,5)P2 in COS or HEK293 cells upon heterologous expression of PIKfyve (30) prevents NH4Cl-triggered vacuoles or restores those due to VacA in these cell types (30, 32). In the same vein, exogenous delivery of PtdIns(3,5)P2 abolishes the ability of VacA to induce cytoplasmic vacuoles in HEK293 cells (32).

Intriguingly, the vacuolation phenotype triggered by both weak bases and VacA cytotoxin is restored by inhibiting vacuolar type H+ ATPase (V-ATPase) with bafilomycin A1 (41, 47). Bafilomycin A1 is a macrolide antibiotic with high inhibitory potency and selectivity towards the vacuolar class of H+ ATPases, which blocks acidification of endosomes, lysosomes and phagosomes at IC50 = 4–400 nM (3, 62). With the aim to gain further mechanistic insight about the vacuolization process triggered by PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction, in this study we have searched for conditions and mechanisms required for manifestation of the aberrant endomembrane vacuoles under PIKfyve or Vps34 deficiency. We report here that inhibition of V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 or inactivation of the GTP-GDP cycle of Rab5a renders cells resistant to cytoplasmic vacuolization despite the inactivation of PIKfyve or Vps34, achieved by pharmacological or genetic approaches. We conclude that the presence of active V-ATPase and functional Rab5a cycle are critical factors mechanistically underlying the formation of cytoplasmic vacuoles under PIKfyve or Vps34 dysfunction and concomitant PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction.1

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies, inhibitors, and constructs.

Mouse monoclonal anti-LAMP1 antibody H4A3 was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). Goat polyclonal anti-early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) antibodies (N-19) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Polyclonal anti-PIKfyve and anti-GDI (used for equal loading) antibodies were previously described (52). Two independent anti-Vps34 antibodies were kind gifts by Dr. J. Backer and Dr. W. Maltese. YM201636 (the pyridofuropyrimidine compound [6-amino-N-(3-(4-(4-morpholinyl)pyrido[3′,2′:4,5]furo[3,2-d]pyrimidin-2-yl)phenyl)-3-pyridine carboxamide] was purchased from Symansis NZ (Timaru, New Zealand) and used as recommended by the manufacturer. Bafilomycin A1 (no. B-1793), chloroquine (no. C-6628), and wortmannin (no. W-1628) were purchased from Sigma. The cDNA constructs were previously described (29).

Cell lines and treatments with inhibitors.

COS7 (African green monkey kidney) cells, Pikfyvefl/fl mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), and Vps34fl/fl immortalized podocytes derived from the respective conditional knockout (KO) mouse models (24, 65) were grown in high-glucose DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (50 U/ml)/streptomycin (50 μg/ml), as described previously (29). The Pikfyvefl/fl mice (24), donated to the Jackson Laboratory, are under no. 029331, B6(Cg)-Pikfyve<tm1.1Ashi. YM201636, wortmannin, and bafilomycin A1 were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to the indicated final concentrations in complete medium, buffered with 20 mM HEPES. Control cells received an equivalent concentration of the vehicle DMSO, typically 0.1% final concentration. The duration of the inhibitor treatment and the order of the inhibitor application are detailed in the figure legends.

Cell transduction and transient transfection.

Recombinant adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre) and empty adenovirus (Ad) (Vector Core, University of Michigan) were diluted in complete medium to multiplicity of infection = 200 as detailed elsewhere (31). Cells seeded on glass coverslips (22 × 22 mm) were treated with the viral solutions. Twenty-four hours posttransduction, the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. On day 5 postinduction, when the vacuolation in Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs or Vps34fl/fl immortalized podocytes was 75–90%, and the respective proteins were undetectable by immunoblotting, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 for ~20 h.

COS7 cells seeded on glass coverslips (22 × 22 mm) were transiently transfected with cDNAs of pGFP-Rab5aWT, pGFP-Rab5aS34N (0.2 μg/35 mm dish) or pEGFP-HA-PIKfyveK1831E (1.5 μg/35 mm dish) as previously described (29) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) and the manufacturer protocols. Protein expression was carried out for 16–18 h, when cells were treated as detailed in the figure legends.

Immunofluorescence, fluorescence, and light microscopy.

Cells seeded on glass coverslips (22 × 22-mm) were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde/PBS, pH 7.3, for 30 min and stained for endogenous LAMP1 and EEA1, following saponin permeabilization as described earlier (29). For LAMP1 staining, cells were incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-LAMP1 antibody (1 μg/ml) followed by Alexa568 anti-mouse secondary antibody (2 μg/ml; Molecular Probes). Cells were further incubated with goat anti-EEA1 antibodies (5 μg/ml) followed by FITC anti-goat secondary antibody (6 μg/ml; Jackson Immuno Research). Cells were viewed under 40× or 60×-oil lenses with a Nikon Eclipse TE200 inverted fluorescence microscope as specified in the figure legends. Images were captured with a SPOT RT Slider charge-coupled device camera. In the pEGFP-transfected cells, following fixation, GFP signals were captured by a standard green fluorescence filter. The phase-contrast images were captured by the differential interference contrast (DIC). Where indicated, coverslips were observed by motorized inverted confocal microscope (model 1X81, Olympus, Melville, NY) with an Uplan Apo objective. Images were captured using a cooled charge-coupled device 12-bit camera (Hamamatsu).

Immunoblotting.

Lysates from Pikfyve KO or Vps34 KO cells were collected in RIPA-buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl buffer, pH 8.0, containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate), supplemented with 1 × protease (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin and 1 mM benzamidine) inhibitors. Immunoblotting with anti-PIKfyve or anti-Vps34 antibodies was performed following protein separation by SDS-PAGE and electrotransfer as specified elsewhere (31).

Statistical analyses.

For quantitation, at least 100–200 individual cells/condition were inspected in at least 3 separate experiments. Cells were classified as vacuolating if they exhibited >7–8 perinuclear vacuoles/cell. Data were subjected to statistical analysis of variance using Student's t-test, with P < 0.05 considered significant. In the occasions when the observed effects were “all or none,” we used statistics of categorical data as described (43), with statistical significance (P < 0.0001) indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Bafilomycin A1 both rescues and prevents formation of cytoplasmic vacuoles due to PIKfyve inhibition by YM201636.

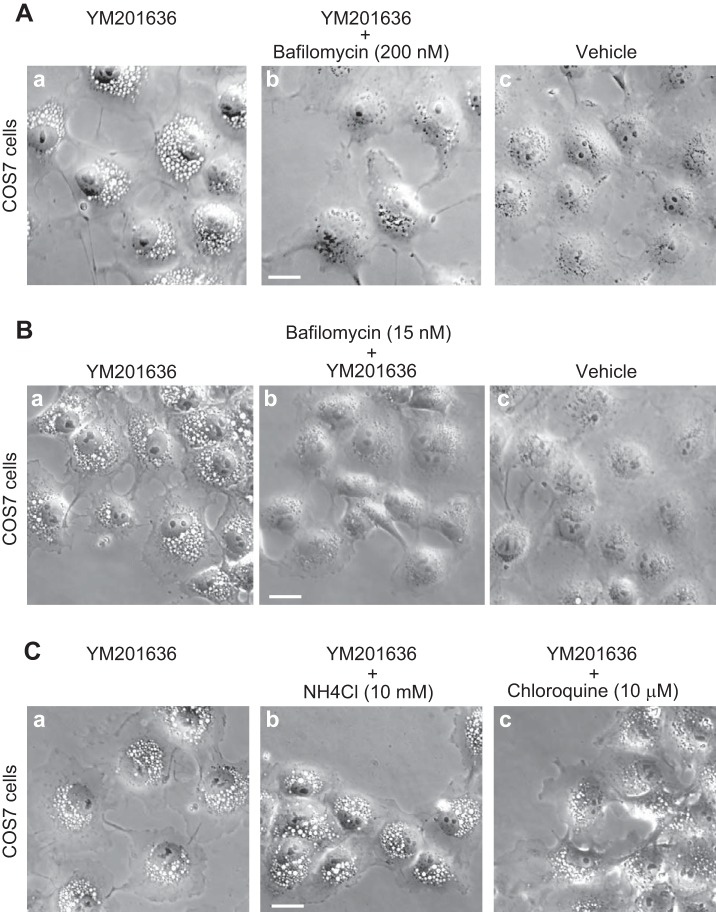

Consistent with previous observations in COS7 and other mitotic cell types, we found that 40–120 min treatment of COS7 with 800 nM of the YM201636 compound, a specific PIKfyve pharmacological inhibitor with an IC50 = 33 nM (36, 50), triggered the formation of multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles filling the entire cell (Fig. 1A). It should be emphasized that under the dose of the YM201636 treatment, some residual levels (∼20%) of cellular PtdIns(3,5)P2 still remain as found by us and others (36, 50). Surprisingly, V-ATPase inhibition by bafilomycin A1 at 200 nM, a concentration that blocks endosome acidification in different cell types (3, 38, 62), added 40 min subsequent to YM201636 completely restored the vacuolation phenotype back to normal cell morphology as demonstrated by light microscopy (Fig. 1A). By contrast, administration of the vehicle (DMSO, 0.1%) in control YM201636-treated COS7 cells had no effect on the aberrant phenotype (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, only short cell pretreatment (60 min) with a concentration of bafilomycin A1 as low as 15 nM prior to further addition of the YM201636 compound prevented the formation of cytoplasmic vacuoles for a duration of 2–24 h posttreatment (Fig. 1B and not shown). To reveal if the reversal of the aberrant vacuolation is due to the V-ATPase inhibition or global compartment alkalinization, 40 min subsequent to YM201636 treatment of COS7 cells we added this time NH4Cl (10 mM) or chloroquine (10 μM), two compounds that increase pH in a number of compartments. Remarkably, unlike bafilomycin A1, neither NH4Cl nor chloroquine was able to effectively rescue the cell vacuolation phenotype (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that the selective inhibition of V-ATPase results in sustained reversal or complete prevention of the formation of characteristic cytoplasmic vacuoles induced by PIKfyve pharmacological inhibition.

Fig. 1.

Bafilomycin A1, but not NH4Cl or chloroquine, treatment dissipates or prevents the cytoplasmic vacuoles triggered by PIKfyve inhibition with YM201636 in COS7 cells. A: cells were treated with YM201636 (800 nM in DMSO) for 120 min at 37°C. Bafilomycin A1 (200 nM in DMSO) or the DMSO vehicle (0.1%) was included during the final 80 min of the YM201636 incubation as indicated. Cells were then fixed and viewed by light microscopy. Notably, bafilomycin A1 dissipated the YM201636-induced multiple vacuoles. B: cells were first pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (15 nM) or DMSO (0.05%) for 60 min at 37°C prior to further addition of YM201636 (800 nM) for additional 120 min, when the cells were fixed and viewed by light microscopy. C: cells were treated with YM201636 (800 nM in DMSO) for 120 min at 37°C. NH4Cl (10 mM) or chloroquine (10 μM) was included during the final 80 min of the YM201636 incubation as indicated. A–C: presented are typical phase-contrast images out of 3 independent experiments with similar results. In each experiment at least 200 cells/condition from several random fields were observed. Lack of multiple vacuoles upon bafilomycin A1 treatment was seen in ∼99% of the monitored cells in each experiment; P < 0.0001. Bar, 10 μm.

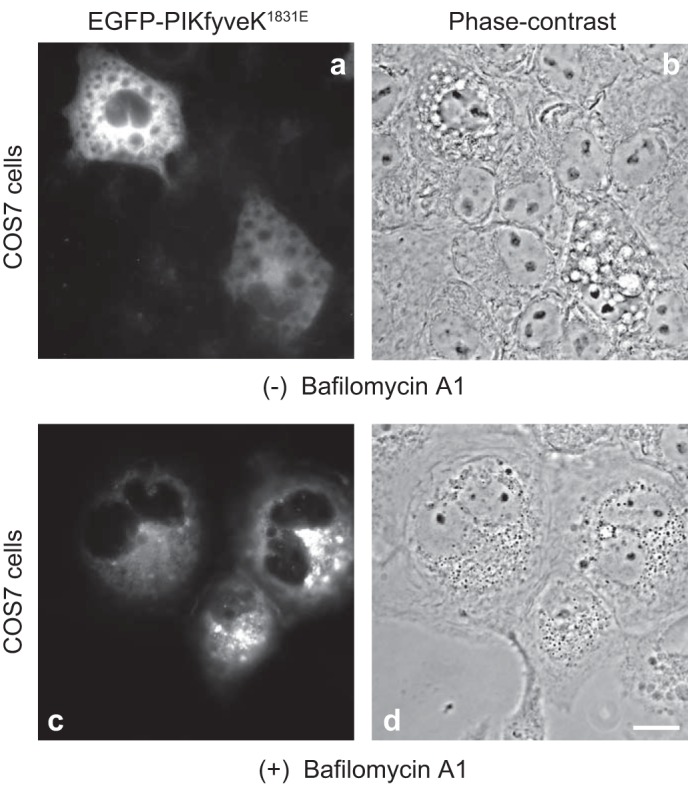

Bafilomycin A1 rescues the cytoplasmic vacuoles triggered by expression of dominant-negative kinase-deficient PIKfyveK1831E.

One could assume that the observed reversal of the vacuolation by bafilomycin A1 may be related to a reduction in the effective endosomal concentration of YM201636. The rationale for such a probability is the fact that, structurally, YM201636 is an organic amine. Amine compounds are thought to be sequestered by various membrane compartments and/or acquire decreased uptake in the presence of bafilomycin A1 (41). Therefore, we sought to determine whether or not bafilomycin A1 is capable of reversing the vacuolation phenotype if triggered by the YM201636-independent inhibition of endogenous PIKfyve. We used the dominant-negative kinase-deficient PIKfyveK1831E mutant whose ability to induce massive endomembrane vacuolation has been well characterized (57). The PIKfyveK1831E mutant operates through displacing the endogenous PIKfyve protein from the ternary PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3 complex, triggering massive vacuolation, compounded by the active PtdIns(3,5)P2 phosphatase Sac3 present in the mutant complex (25). As illustrated in Fig. 2, treatment with bafilomycin A1 (60 min) of massively vacuolating COS7 cells expressing EGFP-PIKfyveK1831E resulted in a complete disappearance of PIKfyveK1831E-triggered vacuoles. Therefore, bafilomycin A1-dependent reversal of the vacuolation phenotype is not an artifact of the plausible YM201636 “trapping.”

Fig. 2.

Bafilomycin A1 rescues the cytoplasmic vacuoles triggered by expression of dominant-negative kinase-deficient PIKfyveK1831E in COS cells. Cells were transiently transfected with the cDNA of pEGFP-HA-PIKfyveK1831E for 24 h, then treated with DMSO (0.1%) or with bafilomycin A1 (200 nM in DMSO) at 37°C for 60 min and processed for fluorescence microscopy. Shown are typical fluorescence and phase-contrast images illustrating multiple vacuoles in vehicle-treated transfected pEGFP-HA-PIKfyveK1831E cells, with EGFP-PIKfyveK1831E-positive signals often seen on the vacuole perimeter membrane (panels a and b), and lack of vacuoles in EGFP-PIKfyveK1831E positive cells after bafilomycin A1 treatment, with the appearance of a punctate pattern for EGFP-PIKfyveK1831E-positive fluorescence (panels c and d). Lack of multiple vacuoles upon bafilomycin A1 treatment was seen in ∼99% of transfected cells in each of the three experiments; P < 0.0001. The binucleation seen in the two bafilomycin A1-treated cells was not a consistent observation. Bar, 10 μm.

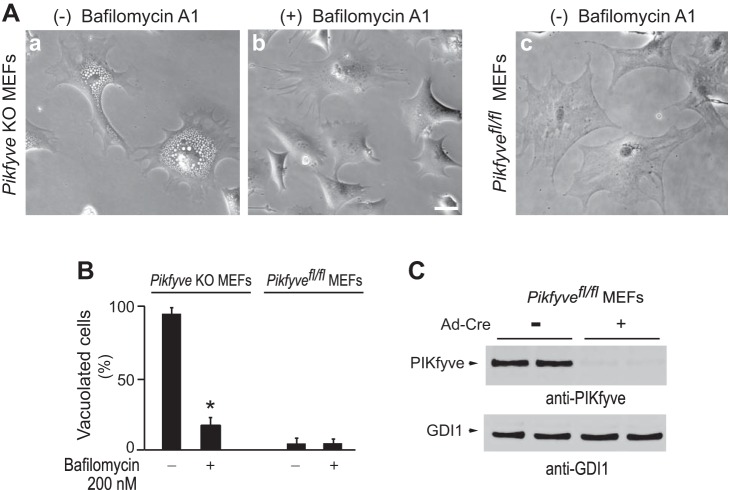

Bafilomycin A1 dissipates the cytoplasmic vacuoles upon PIKfyve KO.

Studies in a number of dividing cells have revealed that PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels should be substantially reduced, i.e., >50% of the individual control levels, in order for the cytoplasmic vacuolization defect to occur (24). Thus it could be assumed that bafilomycin A1 treatment might increase PtdIns(3,5)P2 production through, presumably, activating endogenous PIKfyve, present under PIKfyveK1831E expression. Likewise, the incomplete PIKfyve inhibition with 800 nM of YM201636, evidenced by the 20% residual PtdIns(3,5)P2 cellular amounts (36), could become more prominent under the continued presence of bafilomycin A1. With these caveats in mind, we opted for a cell system in which PIKfyve protein was completely eliminated. To this end, we used MEFs derived from genetically modified Pikfyvefl/fl mice and excised the floxed alleles by transduction with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase. As characterized previously (31) and confirmed herein, treatment with Ad-Cre, but not with empty Ad, resulted in barely detectable PIKfyve protein levels and a profound vacuolation phenotype, affecting ∼90% of the MEFs on day 5 posttransduction (Fig. 3, A–C); hence, hereafter we refer to this condition as Pikfyve KO. We next treated the vacuolating Pikfyve KO MEFs with bafilomycin A1 or with a corresponding concentration of the vehicle. Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs transduced with empty adenovirus were used as controls for the effect of bafilomycin A1 or vehicle treatments. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, there was massive vacuolation in vehicle-treated Pikfyve KO MEFs. By contrast, bafilomycin A1 treatment (200 nM) produced a remarkable reversal of the aberrant vacuoles in ∼85% of the vacuolated Pikfyve KO MEFs (Fig. 3, A and B). Vacuoles in the empty virus-infected control Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs that received bafilomycin A1 or vehicle were only occasionally seen (in <5% of total cells, Fig. 3B). It should be noted, however, that ∼15% of the Pikfyve KO MEFs that exhibited extremely large vacuoles, sometimes a giant single vacuole, did not respond to bafilomycin A1 (Fig. 3B). This suggests that the extreme vacuolation in some cells makes the process irreversible. It is likely that these cells might have developed features resembling the nonapoptotic programmed cell death found in cells vacuolating through a process called “methuosis” (40). Notwithstanding, our data presented above demonstrate that bafilomycin A1 is capable of restoring the cytoplasmic vacuolation back to normal cell morphology under the complete absence of PIKfyve.

Fig. 3.

Bafilomycin A1 rescues the cytoplasmic vacuoles in Pikfyve KO MEFs. A: Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs cultured in complete medium were transduced with adenovirus, either empty (Ad) or expressing Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre) for 24 h, when the medium was replaced. Four days later, <2% of the control Ad-transduced cells vacuolated whereas ∼90% of the Ad-Cre-infected cells showed typical translucent cytoplasmic vacuoles due to Pikfyve KO (31). At this stage, Pikfyve KO or Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs were treated or not treated (received the vehicle, 0.1% DMSO) with bafilomycin A1 (200 nM) for ∼20 h and then fixed. Shown are typical phase-contrast images of Pikfyve KO MEFs demonstrating extreme cytoplasmic vacuolization by vehicle (panel a) and dissipation of the vacuoles by bafilomycin A1 treatments (panel b). Illustrated are Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs transduced with empty Ad and treated with vehicle (panel c). Bar, 10 μm. B: quantitative analysis of data in A, presented as the percentage of vacuolated cells, determined by counting at least 100 cells/condition from three or more random fields in 4 separate experiments. Note, bafilomycin A1 was not effective in all Pikfyve KO MEFs; ∼15% of the cells remained with vacuoles following treatment, when they died. *P < 0.001. C: a representative Western blot with anti-PIKfyve antibodies of duplicate lysates derived from parallel dishes of Pikfyvefl/fl MEFs on day 5 following Ad-Cre or Ad transduction, illustrating undetectable levels of the PIKfyve protein in Pikfyve KO MEFs. The blot was reprobed with anti-GDI1 antibodies for equal loading.

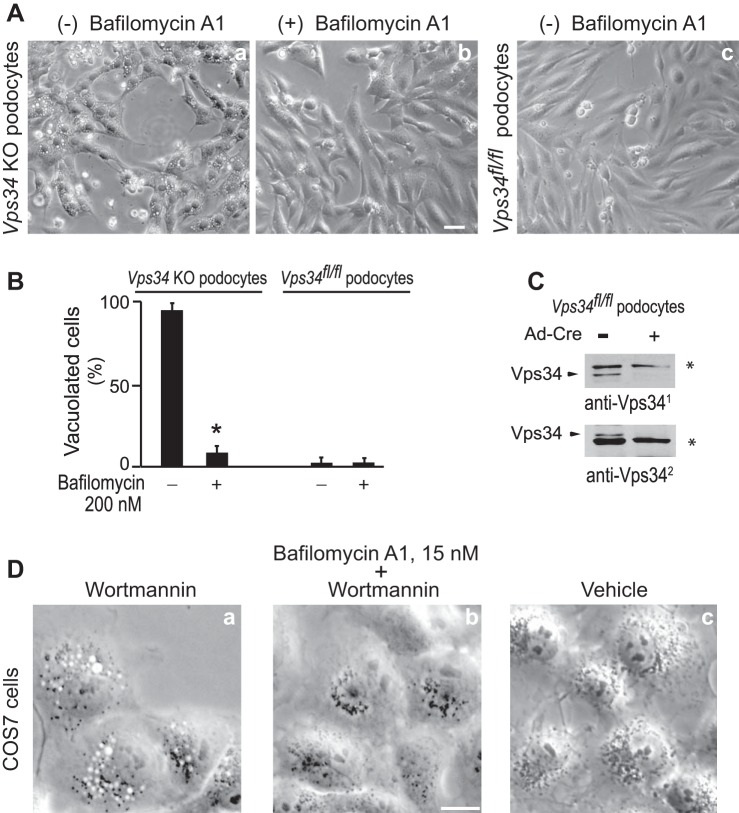

Bafilomycin A1 dissipates and prevents cytoplasmic vacuolation induced by Vps34 KO or PI3K inhibition.

The results presented above demonstrating bafilomycin A1 rescue and/or preclusion of cytoplasmic vacuolization despite the drastic and continued reduction in PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels suggest that active V-ATPase is a prerequisite for the aberrant phenotype induced by perturbation or KO of the PIKfyve protein. We next sought to determine whether under PIKfyve intactness but reduced PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels, bafilomycin A1 will restore the vacuolation phenotype that is manifested under these conditions. To this end, we took advantage of Vps34fl/fl podocytes, in which transduction with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase, but not with empty Ad, caused Vps34 loss and triggered multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles, distinct from autophagosomes [(31) and Fig. 4, A–C]. We have previously shown that this morphological defect in Vps34 KO podocytes is due to the absence of Vps34-produced PtdIns3P and concomitant depletion of the substrate source for PIKfyve activity, which causes marked reduction in PtdIns(3,5)P2 production despite the presence of normal levels of the PIKfyve protein (31). Vps34 KO podocytes cultured in complete media and used on day 5 following Ad-Cre-transduction exhibited massive cytoplasmic vacuolation (Fig. 4A), seen in ∼90% of the cells. Strikingly, as with the PIKfyve deficient cells, bafilomycin A1 treatment dissipated the translucent vacuoles, reversing the Vps34 KO podocytes morphology back to normal (Fig. 4, A and B). A similar rescue of the vacuolation has been reported in Vps34 KO MEFs, derived from a Vps34fl/fl mouse model (35) unrelated to the one used herein.

Fig. 4.

Bafilomycin A1 reverses and prevents cytoplasmic vacuolation induced by Vps34 KO or inhibition with wortmannin. A: Vps34fl/fl podocytes cultured in complete media were transduced with adenovirus, either empty (Ad) or expressing Cre recombinase (Ad-Cre) for 24 h, when the virus was removed by media replacement. Four days later, empty Ad-transduced cells had practically no vacuoles (Vps34fl/fl podocytes, panel c) whereas Ad-Cre-infected cells showed typical multiple translucent perinuclear cytoplasmic vacuoles in >90% of the cells (panel a). At this point, Vps34 KO and Vps34fl/fl podocytes were treated with bafilomycin A1 (200 nM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) at 37°C for ∼20 h, then fixed and viewed by light microscopy. Shown are typical phase-contrast images of Vps34 KO podocytes demonstrating extreme cytoplasmic vacuolation by vehicle (panel a) and dissipation of the vacuoles by bafilomycin A1 (panel b). B: quantification of data in A showing that whereas bafilomycin A1 did not affect Ad-treated Vps34fl/fl cells, it significantly reduced the vacuolated Vps34 KO podocytes, *P < 0.001. C: representative Western blot of lysates derived from Vps34fl/fl podocytes on day 5 following Ad-Cre or Ad transduction, probed with two different anti-Vps34 antibodies, showing undetectable levels of the Vps34 protein under Ad-Cre (+). *Nonspecific bands illustrating equal loading. D: COS7 cells were pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (15 nM) (panel b) or DMSO (panel a) for 60 min at 37°C prior to further addition of wortmannin (200 nM) for 120 min. Control cells received only vehicle (panel c). Cells were fixed and viewed by light microscopy. Note the complete absence of perinuclear translucent vacuoles in bafilomycin A1-pretreated cells (panel b) and their presence in all vehicle-pretreated control cells (panel a). Lack of multiple vacuoles upon bafilomycin A1 treatment was seen in ∼99% of the monitored cells in each of the three experiments; P < 0.0001.

We and others have provided evidence for Vps34-independent PI3Ks, feeding directly or indirectly into the endosomal PtdIns3P pool (13, 33, 48, 53, 63) and supplying PtdIns3P substrate for PIKfyve activity (4, 31). As Vps34, many PI3Ks are wortmannin-sensitive (13, 63), with wortmannin treatment triggering cytoplasmic vacuolation in several cell types, including COS7 (30). To reveal if bafilomycin A1 prevents formation of wortmannin-induced vacuoles in COS7 cells, as in the case of YM201636, subsequent to pretreatment with a low dose of bafilomycin A1, we added wortmannin at 200 nM. It should be noted that at this dose, wortmannin does not inhibit directly PIKfyve [ID50 = 600 nM; (52)]. As expected, wortmannin treatment of control COS7 cells triggered massive cytoplasmic vacuolation (Fig. 4D). Cell pretreatment with bafilomycin A1 completely prevented the appearance of cytoplasmic vacuolation under these conditions (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that, as under the conditions of PIKfyve perturbation, inhibition of V-ATPase dissipates and precludes the cytoplasmic vacuolation triggered by Vps34 disruption or pharmacological inhibition of PI3Ks.

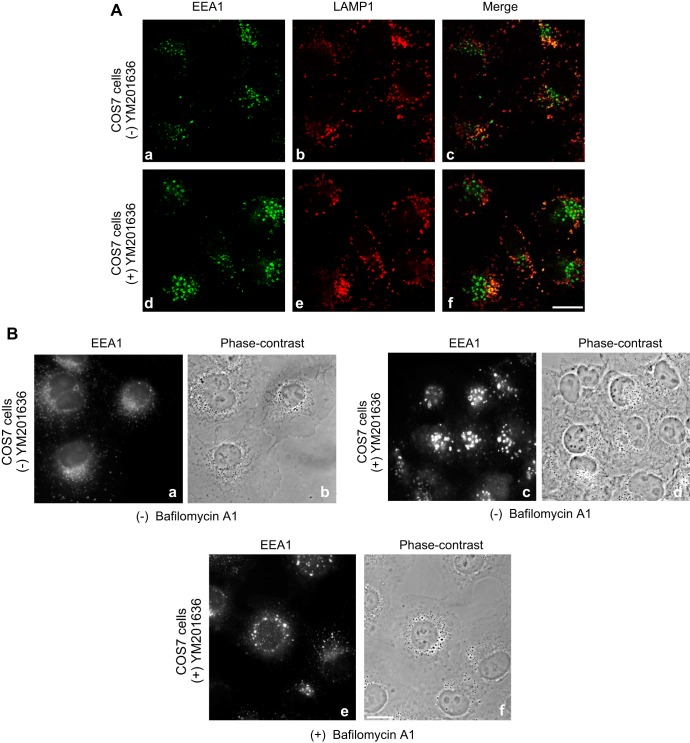

Only early endosome dilation upon short treatment with YM201636, which is also prevented by bafilomycin A1 pretreatment.

Our previous studies in COS7 cells expressing the dominant-negative kinase-deficient PIKfyveK1831E mutant for a short time period (12 h posttransfection) have identified that the onset of PtdIns(3,5)P2 functional requirement is at the early endosomes (29). Thus, whereas there was no manifestation of the vacuolation phenotype under this short-term expression, we found a major defect in the form of dilation of the PIKfyveK1831E-positive endosomal structures that also harbored early endosomal markers such as EEA1 and Rab5aWT (29). Consistent with the role of PIKfyve in EVC detachment/MVB maturation revealed in vitro by endosome reconstitution assays (51), we also observed dislocation of the LAMP1 and Rab7-positive late endosomal structures from their typical perinuclear position (29). To determine whether such changes are phenocopied by PIKfyve pharmacological inhibition, COS7 cells were treated with YM201636 for a time period of only 15 min, when they were fixed and processed with EEA1 and LAMP1 antibodies for confocal microscopy. Consistent with our prediction, whereas vacuolation phenotype was not apparent, this short treatment with YM201636 led to a marked dilation of the EEA1-positive early endosomes that were concentrated at the perinuclear region (Fig. 5, A and B). Contrary to EEA1 endosome enlargement, the LAMP1-positive vesicles were not dilated. Rather, they appeared more distinctly segregated from the EEA1 enlarged vesicles compared with vehicle-treated control cells (Fig. 5A, panel f vs. c).

Fig. 5.

Absence of vacuoles but presence of EEA1-positive enlarged endosomes by short inhibition with YM201636 in COS7 cells. A: cells were treated with YM201636 (800 nM) (panels d–f) or with the vehicle (panels a–c) for 15 min at 37°C, then fixed, immunostained consecutively for LAMP1 or EEA1, and observed by confocal microscope. Shown are typical confocal immunofluorescence images for EEA1 (panels a and d) or LAMP1 (panels b and e) and the merge of the two signals (panels c and f). Apparent are dilated EEA1-positive early endosomes (panel a vs. d), unaltered size of LAMP1-stained vesicles (panels b and e), and more segregated LAMP1 immunoreactivity relative to that of EEA1 (panel c vs. f) by the short YM201636 treatment. B: cells were first pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (15 nM) or DMSO (0.05%) for 60 min at 37°C prior to further addition of vehicle or YM201636 (800 nM) for an additional 15 min as indicated. Cells were fixed and viewed by light microscopy. Apparent is massive dilation of EEA1-positive early endosome perinuclearly upon YM201636 (panel c vs. a), which is absent if cells are pretreated with bafilomycin A1 (panel c vs. e). Bar, 10 μm.

To reveal if inhibition of V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 also prevents this early endosome enlargement, COS7 cells were first pretreated with bafilomycin A1 for 60 min, when the YM201636 inhibitor was administered for 15 min. As illustrated in Fig. 5B, panels e and f, bafilomycin A1 pretreatment prevented the marked dilation of early endosomes, seen by short treatment with the PIKfyve inhibitor alone (panels c and d).

Vacuolization by PIKfyve or Vps34 inhibition or gene inactivation requires functional Rab5a cycle.

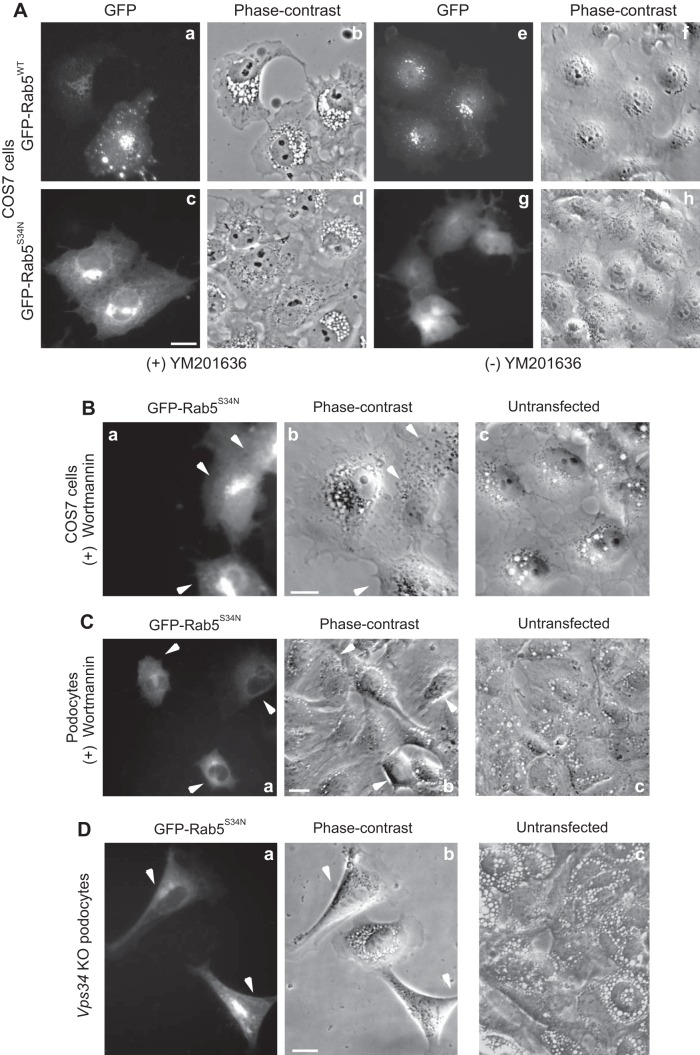

The GDP-GTP Rab5 cycle regulates the homotypic and heterotypic fusion within the endosomal compartments during the early stages of endocytosis (15). Given our findings that early endosomes are the primary compartment affected by short-term PIKfyve inhibition with YM201636, we next examined whether the Rab5a-GTPase is part of the mechanism regulating the cytoplasmic vacuolation triggered by PIKfyve deficiency and PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction. To this end, we transiently transfected COS7 cells with the dominant-negative constitutively-inactive GDP-bound GFP-Rab5aS34N mutant that prevents the Rab5 cycle and inhibits fusion (60). As a control, we used cells transiently transfected with Rab5aWT, because expression of constitutively-active GTP-bound Rab5aQ79L by itself triggers formation of dilated endosomal structures in this cell type (29). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were treated for 2 h with YM201636 to trigger vacuolation and then observed by fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy. Remarkably, GFP-Rab5aS34N-expressing COS7 cells did not vacuolate despite the YM201636 continued presence (Fig. 6A, panels c and d). By contrast, the nontransfected neighboring cells exhibited the typical multiple perinuclear vacuoles induced by the YM201636 treatment (Fig. 6A, panels c and d). Consistent with the requirement of active Rab5a for YM201636-triggered vacuolation, GFP-Rab5aWT expressing cells showed multiple perinuclear vacuoles similarly to nontransfected neighboring cells on the dish (Fig. 6A, panels a and b). These data implicate the key role of Rab5 in the YM201636-induced cytoplasmic vacuolation and suggest that a functional cycle of Rab5a is critical for manifestation of the vacuolation phenotype under PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction.

Fig. 6.

Constitutively inactive Rab5aS34N expression precludes the vacuolation triggered by PIKfyve or Vps34 inhibition. A: COS7 cells, transfected overnight with cDNAs of pGFP-Rab5aWT or pGFP-Rab5aS34N, were treated for 2 h at 37°C with YM201636 (800 nM) (panels a–d) or with vehicle (−YM201636, panels e–h), then fixed and viewed by fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy. Note the presence of translucent cytoplasmic vacuoles in Rab5aWT-expressing cells under the YM201636 treatment, which are at a similar size and number as the vacuoles in the neighboring nonexpressing cells (panels a and b). Rab5aS34N-expressing cells, in contrast to the neighboring nonexpressing cells, are devoid of cytoplasmic vacuoles (panels c and d) as are the control vehicle-treated cells (panels e–h). B and C: COS7 cells (B) or podocytes (C) were transfected with the cDNA of pGFP-Rab5aS34N (panels a and b) or left untransfected (panel c) for 24 h, when they were treated with wortmannin (200 nM) for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then fixed and viewed by fluorescence (panel a) and phase-contrast microscopy (panels b and c). Shown are typical vacuole-free GFP-Rab5aS34N-expressing cells (arrowheads, panels a and b) and multiple vacuoles in nonexpressing neighboring vacuolating cells or in untransfected control cells (panels b and c). A–C: lack of multiple vacuoles by GFP-Rab5aS34N expression was seen in ∼99% of transfected cells in each of the three experiments/condition; P < 0.0001. D: Vps34fl/fl podocytes cultured in complete media were transduced with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase for 24 h, when the virus was removed by media replacement. Three days later, podocytes were transfected overnight with cDNA of pGFP-Rab5aS34N (panels a and b) or left untransfected (panel c), then fixed and viewed by fluorescence (panel a) and phase-contrast microscopy (panels b and c). At this point, Vps34 KO podocytes had vacuoles in ∼90% of the cells. Expression of pGFP-Rab5aS34N prevented the appearance of vacuoles (arrowheads, panels a and b) in ∼60% of pGFP-Rab5aS34N-transfected Vps34 KO podocytes. Bar, 10 μm.

Similarly, expression of the GFP-Rab5aS34N mutant precluded the vacuolation caused by wortmannin in COS7 cells and podocytes (Fig. 6, B and C, panels a and b), confirming earlier observations in HEK293 and breast cancer cells using the inhibitor (7, 20). More importantly, however, expression of GFP-Rab5aS34N inhibited, in part, the appearance of cytoplasmic vacuoles in podocytes with Vps34 gene disruption (Fig. 6D). Similarly to COS7 cells, in podocytes with Vps34 inhibition, expression of GFP-Rab5aWT was ineffective in preventing the vacuolation phenotype (not shown). Together, these data point to the importance of active Rab5 platforms and regulatory GTP-GDP Rab5a cycle for the functionality of the constitutive Vps34-PIKfyve pathway in early endosome processing and endomembrane integrity.

DISCUSSION

Since the development of the dominant-negative kinase-deficient PIKfyveK1831E mutant about 15 years ago, it became apparent that PIKfyve dysfunction and, hence, PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction trigger formation of multiple translucent cytoplasmic vacuoles in many mitotic cell types (30). PIKfyveK1831E mutant operates through displacing the endogenous PIKfyve protein from the ternary complex with Sac3 and ArPIKfyve, causing massive vacuolization, exacerbated by the active PtdIns(3,5)P2 phosphatase Sac3 (25). The dominant-negative mutant was instrumental in determining PIKfyve functionality in maintenance of endomembrane homeostasis and has been widely used along with other more recently developed tools for PIKfyve perturbation (56, 57). In this study we report for the first time that inhibition of the V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 completely rescued the cytoplasmic vacuolation triggered by PIKfyveK1831E expression in COS7 cells (Fig. 2). This effect was reproduced by specific PIKfyve inhibition with the YM201636 compound or by Pikfyve inactivation in genetically modified MEFs (Figs. 1A and 3). Moreover, inhibition of V-ATPase by only a short pretreatment with bafilomycin A1 at low doses precluded the formation of cytoplasmic vacuoles caused by PIKfyve pharmacological inhibition (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we found that perturbation of the regulatory GTP-GDP cycle of Rab5a also restored completely the aberrant phenotype due to PIKfyve dysfunction (Fig. 6A). Next, consistent with Vps34 positioning up-stream of PIKfyve (31), we found that both the V-ATPase inhibition by bafilomycin A1 and the constitutive inactivation of Rab5a functional cycle also dissipated or prevented the vacuolation phenotype triggered by genetic inactivation or pharmacological inhibition of Vps34 in podocytes and COS7, respectively (Figs. 4 and 6, B–D). Overall, these data support a mechanism whereby the manifestation of massive cytoplasmic vacuolation triggered by PtdIns(3,5)P2 deficiency through PIKfyve or Vps34 inactivation requires both a functional regulatory cycle of Rab5a-GTPase and an active V-ATPase.

Several effects of bafilomycin A1 in the endosomal/lysosomal system have been reported previously. These include inhibition of membrane trafficking from early to late endosomes through arresting the formation of ECV intermediates (8, 16), inhibition of homotypic endosomal fusion by affecting the membrane potential (17), and perturbation of endosome/lysosome acidification (3, 62). How these defects are interconnected to mechanistically underlying the dissipation of the cytoplasmic vacuoles due to PIKfyve or Vps34 perturbation, and the concomitant PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction, is currently a matter of speculation. We anticipate that, in this case, the vacuolization-preventive effect of bafilomycin A1 is linked with inhibition of the homotypic endosomal fusion based on the following considerations. First, the morphological defects due to PIKfyveK1831E are associated with profound increases in endosome fusion efficiency as established by a cell-free reconstitution assay monitoring both the homotypic fusion of early endosome and the heterotypic fusion of ECVs/MVBs with late endosomes/lysosomes (29); hence, bafilomycin A1 might counteract this accelerated fusion. This notion is also supported by data in this study revealing that pretreatment with bafilomycin A1 prevented the massive dilation of EEA1-positive early endosomes due to short administration of the YM201636 compound (Fig. 5B). Next, treatment of vacuolated YM201636-treated COS7 cells or vacuolated Vps34 KO podocytes with NH4Cl or chloroquine, conditions that trigger global alkalinization of the endosomal/lysosomal system (18, 41), did not phenocopy the effect of bafilomycin A1 in dissipating the cytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 1, A and C, and data not shown). On the other hand, neither the vacuolation nor the levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 appear to affect the compartment pH or the V-ATPase activity. This conclusion is based on recent quantitative pH measurements in macrophages, which showed unaltered lysosomal acidity despite the profound reduction in PtdIns(3,5)P2 and the massive cytoplasmic vacuolation under PIKfyve inhibition by the YM201636-analog MF4 or apilimod (19). The insensitivity of the lysosomal pH to changes in PtdIns(3,5)P2 is corroborated by observations in yeast where marked increases or ablation of PtdIns(3,5)P2 by inactivation of atg18 (atg18Δ) or the PIKfyve ortholog fab1 (fab1Δ) (11), respectively, do not affect yeast vacuole pH (19). Together, these observations and considerations support the notion that direct inhibition of the proton pump and subsequent arrest of endosomal fusion rather than global endosomal/lysosomal alkalinization underlie the reversal of, or resistance to, cytoplasmic vacuolization under PtdIns(3,5)P2 reduction. Some subtle practically immeasurable changes in endosomal pH could not be excluded.

In addition to PIKfyve or Vps34 dysfunction, cytoplasmic vacuolization in mammalian cells is triggered by a wide range of inductive stimuli, including H. pylori VacA cytotoxin, weak-base-related cationic compounds, constitutively active Ras, quinine-like lipophilic amines, or chalcone-like small molecules (18, 39–41). In most of these examples, the aberrant morphology is in the form of massive macropinocytotic vacuoles, formed due to hyperstimulated macropinocytotic influx and subsequently affecting steps of the endosomal trafficking pathway (39, 40). Whether the PtdIns(3,5)P2 pool is influenced under these conditions or whether increased levels of PIKfyve could dissipate the macropinocytotic vacuoles, as seen with the vacuoles triggered by VacA cytotoxin or weak bases, is unknown (30, 32). Although mechanistic details are still limited, the available data allow the conclusion that the vacuoles under some of the above conditions share several similarities with those formed under the PIKfyve or Vps34 deficiency, including: 1) dissimilarity with autophagosomes; 2) translucent appearance; 3) concentration of early and late endosomal markers on the vacuole-limiting membrane; and 4) sensitivity to inhibition by bafilomycin A1 (18, 31, 39–41; and this study, Figs. 1 and 4). However, major differences exist, the foremost ones being the mechanism of initial generation of the vacuoles, accumulation of Lucifer yellow within the macropinocytotic vacuoles, and independence from the functional cycle of Rab5a GTPase. For example, whereas in this study we observed that the cytoplasmic vacuolization due to YM201636 and wortmannin inhibition in COS7 cells or Vps34 gene inactivation in podocytes was prevented by expression of the GDP-bound constitutively inactive Rab5aS34N mutant that perturbs the Rab5 functional cycle (Fig. 6), the ones triggered by procaine or indole-based chalcone proceeded independently of the Rab5a cycle in smooth muscle and glioblastoma cells, respectively (45, 46). Given observations for increased cell toxicity and nonapoptotic death under pharmacologically-triggered vacuolation in cancer cells (40), further details on the molecular mechanism under each vacuolation condition will be of significant importance.

Our observations that active V-ATPase and a functional GDP-GTP cycle of Rab5a is required for the vacuolation to occur under the PtdIns(3,5)P2 absence or reduction could also shed light as to why some nonmitotic cells never vacuolate. For example, terminally differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes in culture, as opposed to the rapidly dividing precursor 3T3L1 fibroblastic cells, do not form cytoplasmic vacuoles under pharmacological inhibition or expression of the dominant-interfering kinase-deficient mutant of PIKfyve (27, 50). Likewise, fat cells, muscle cells, or glomeruli podocytes in the context of the respective adipose-specific, muscle-specific or podocytes-specific mouse model with Pikfyve inactivation through Cre recombinase expression driven by the corresponding promoters, do not exhibit cytoplasmic vacuoles in situ (22, 23, 28, 64). Whereas in these mouse models incomplete Pikfyve inactivation might be an admissible cause for lack of vacuoles, it is remarkable that mitotic podocytes that outgrow in a culture from the very same nonvacuolating terminally differentiated glomerular podocytes exhibit the vacuolation phenomenon (64). Concordantly, Pikfyve inactivation in cells that are under robust and constant turnover, such as proximal tubular and intestinal epithelial cells, readily trigger cytoplasmic vacuoles in situ in the respective tissue-specific Pikfyve KO mouse model (61, 64). Based on these data and those presented in this study, we suggest that upon cell terminal differentiation and loss of proliferating capacity, the robustness of the mechanisms regulating V-ATPase activity and/or the GDP-GTP cycle of Rab5a might fade away, a notion that could have far-reaching implication in selective targeting of proliferating tumor cells in the background of differentiated tissues.

GRANTS

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK-058058) (to A. Shisheva), (DK-097027) (to P. Garg), and American Diabetes Association (BS-13-161) (to A. Shisheva).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.M.C., O.C.I., and D.S. performed experiments; L.M.C., O.C.I., D.S., and A.S. analyzed data; L.M.C., O.C.I., D.S., P.G., and A.S. interpreted results of experiments; L.M.C., O.C.I., and D.S. prepared figures; L.M.C., O.C.I., D.S., P.G., and A.S. edited and revised manuscript; L.M.C., O.C.I., D.S., P.G., and A.S. approved final version of manuscript; A.S. conception and design of research; A.S. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rochelle La Macchio for the outstanding secretarial assistance. The senior author expresses gratitude to the late Violeta Shisheva for many years of support.

Footnotes

This article is the topic of an Editorial Focus by Loredana Saveanu and Sophie Lotersztajn (49a).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bechtel W, Helmstadter M, Balica J, Hartleben B, Kiefer B, Hrnjic F, Schell C, Kretz O, Liu S, Geist F, Kerjaschki D, Walz G, Huber TB. Vps34 deficiency reveals the importance of endocytosis for podocyte homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 727–743, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonifacino JS, Rojas R. Retrograde transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 568–579, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 7972–7976, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridges D, Ma JT, Park S, Inoki K, Weisman LS, Saltiel AR. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate plays a role in the activation and subcellular localization of mechanistic target of rapamycin 1. Mol Biol Cell 23: 2955–2962, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown WJ, Goodhouse J, Farquhar MG. Mannose-6-phosphate receptors for lysosomal enzymes cycle between the Golgi complex and endosomes. J Cell Biol 103: 1235–1247, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai X, Xu Y, Cheung AK, Tomlinson RC, Alcazar-Roman A, Murphy L, Billich A, Zhang B, Feng Y, Klumpp M, Rondeau JM, Fazal AN, Wilson CJ, Myer V, Joberty G, Bouwmeester T, Labow MA, Finan PM, Porter JA, Ploegh HL, Baird D, De Camilli P, Tallarico JA, Huang Q. PIKfyve, a class III PI kinase, is the target of the small molecular IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor apilimod and a player in Toll-like receptor signaling. Chem Biol 20: 912–921, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Wang Z. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis by wortmannin through activation of Rab5 rather than inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. EMBO Rep 2: 842–849, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clague MJ, Urbe S, Aniento F, Gruenberg J. Vacuolar ATPase activity is required for endosomal carrier vesicle formation. J Biol Chem 269: 21–24, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori factors associated with disease. Gastroenterology 117: 257–261, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lartigue J, Polson H, Feldman M, Shokat K, Tooze SA, Urbe S, Clague MJ. PIKfyve regulation of endosome-linked pathways. Traffic 10: 883–893, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dove SK, Piper RC, McEwen RK, Yu JW, King MC, Hughes DC, Thuring J, Holmes AB, Cooke FT, Michell RH, Parker PJ, Lemmon MA. Svp1p defines a family of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate effectors. EMBO J 23: 1922–1933, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eskelinen EL, Prescott AR, Cooper J, Brachmann SM, Wang L, Tang X, Backer JM, Lucocq JM. Inhibition of autophagy in mitotic animal cells. Traffic 3: 878–893, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falasca M, Maffucci T. Regulation and cellular functions of class II phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochem J 443: 587–601, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Futter CE, Collinson LM, Backer JM, Hopkins CR. Human VPS34 is required for internal vesicle formation within multivesicular endosomes. J Cell Biol 155: 1251–1264, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorvel JP, Chavrier P, Zerial M, Gruenberg J. rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell 64: 915–925, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruenberg J, Stenmark H. The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 317–323, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond TG, Goda FO, Navar GL, Campbell WC, Majewski RR, Galvan DL, Pontillon F, Kaysen JH, Goodwin TJ, Paddock SW, Verroust PJ. Membrane potential mediates H(+)-ATPase dependence of “degradative pathway” endosomal fusion. J Membr Biol 162: 157–167, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henics T, Wheatley DN. Cytoplasmic vacuolation, adaptation and cell death: a view on new perspectives and features. Biol Cell 91: 485–498, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho CY, Choy CH, Wattson CA, Johnson DE, Botelho RJ. The Fab1/PIKfyve phosphoinositide phosphate kinase is not necessary to maintain the pH of lysosomes and of the yeast vacuole. J Biol Chem 290: 9919–9928, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houle S, Marceau F. Wortmannin alters the intracellular trafficking of the bradykinin B2 receptor: role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Rab5. Biochem J 375: 151–158, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huotari J, Helenius A. Endosome maturation. EMBO J 30: 3481–3500, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Delvecchio K, Feng HZ, Cartee GD, Jin JP, Shisheva A. Muscle-specific Pikfyve gene disruption causes glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, adiposity, and hyperinsulinemia but not muscle fiber-type switching. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E119–E131, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Delvecchio K, Rillema JA, Shisheva A. Unexpected severe consequences of Pikfyve deletion by aP2- or Aq-promoter-driven Cre expression for glucose homeostasis and mammary gland development. Physiol Reports 4: e12812, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Delvecchio K, Xie Y, Jin JP, Rappolee D, Shisheva A. The phosphoinositide kinase PIKfyve is vital in early embryonic development: preimplantation lethality of PIKfyve−/− embryos but normality of PIKfyve+/− mice. J Biol Chem 286: 13404–13413, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Fenner H, Shisheva A. PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3 core complex: contact sites and their consequence for Sac3 phosphatase activity and endocytic membrane homeostasis. J Biol Chem 284: 35794–35806, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Mlak K, Kanzaki M, Pessin J, Shisheva A. Functional dissection of lipid and protein kinase signals of PIKfyve reveals the role of PtdIns 3,5-P2 production for endomembrane integrity. J Biol Chem 277: 9206–9211, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Mlak K, Shisheva A. Requirement for PIKfyve enzymatic activity in acute and long-term insulin cellular effects. Endocrinology 143: 4742–4754, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Shisheva A. Fat cell-specific inactivation of one or both alleles in mice causes insulin resistance (Abstract 26). Proceedings of the 3rd Annual WSU/UM Joint Physiology Symposium, Detroit 2012. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University, 2012. http://physiology.med.wayne.edu/pdfs/psl2012abstracts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Shisheva A. Localized PtdIns 3,5-P2 synthesis to regulate early endosome dynamics and fusion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C393–C404, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Shisheva A. Mammalian cell morphology and endocytic membrane homeostasis require enzymatically active phosphoinositide 5-kinase PIKfyve. J Biol Chem 276: 26141–26147, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Venkatareddy M, Tisdale E, Garg P, Shisheva A. Class III PI 3-kinase is the main source of PtdIns3P substrate and membrane recruitment signal for PIKfyve constitutive function in podocyte endomembrane homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853: 1240–1250, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Yoshimori T, Cover TL, Shisheva A. PIKfyve Kinase and SKD1 AAA ATPase define distinct endocytic compartments. Only PIKfyve expression inhibits the cell-vacuolating activity of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin. J Biol Chem 277: 46785–46790, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivetac I, Munday AD, Kisseleva MV, Zhang XM, Luff S, Tiganis T, Whisstock JC, Rowe T, Majerus PW, Mitchell CA. The type Ialpha inositol polyphosphate 4-phosphatase generates and terminates phosphoinositide 3-kinase signals on endosomes and the plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell 16: 2218–2233, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaber N, Dou Z, Chen JS, Catanzaro J, Jiang YP, Ballou LM, Selinger E, Ouyang X, Lin RZ, Zhang J, Zong WX. Class III PI3K Vps34 plays an essential role in autophagy and in heart and liver function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 2003–2008, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaber N, Zong WX. Vps34 controls Rab7 to regulate endocytic trafficking (Abstract J2 2013). Proceedings of the Keystone Symposia 2015 PI 3-Kinase Signalling Pathways in Disease, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jefferies HB, Cooke FT, Jat P, Boucheron C, Koizumi T, Hayakawa M, Kaizawa H, Ohishi T, Workman P, Waterfield MD, Parker PJ. A selective PIKfyve inhibitor blocks PtdIns(3,5)P(2) production and disrupts endomembrane transport and retroviral budding. EMBO Rep 9: 164–170, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson EE, Overmeyer JH, Gunning WT, Maltese WA. Gene silencing reveals a specific function of hVps34 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in late versus early endosomes. J Cell Sci 119: 1219–1232, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson LS, Dunn KW, Pytowski B, McGraw TE. Endosome acidification and receptor trafficking: bafilomycin A1 slows receptor externalization by a mechanism involving the receptor's internalization motif. Mol Biol Cell 4: 1251–1266, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitambi SS, Toledo EM, Usoskin D, Wee S, Harisankar A, Svensson R, Sigmundsson K, Kalderen C, Niklasson M, Kundu S, Aranda S, Westermark B, Uhrbom L, Andang M, Damberg P, Nelander S, Arenas E, Artursson P, Walfridsson J, Forsberg Nilsson K, Hammarstrom LG, Ernfors P. Vulnerability of glioblastoma cells to catastrophic vacuolization and death induced by a small molecule. Cell 157: 313–328, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maltese WA, Overmeyer JH. Methuosis: nonapoptotic cell death associated with vacuolization of macropinosome and endosome compartments. Am J Pathol 184: 1630–1642, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marceau F, Bawolak MT, Lodge R, Bouthillier J, Gagne-Henley A, Gaudreault RC, Morissette G. Cation trapping by cellular acidic compartments: beyond the concept of lysosomotropic drugs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 259: 1–12, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min SH, Suzuki A, Stalker TJ, Zhao L, Wang Y, McKennan C, Riese MJ, Guzman JF, Zhang S, Lian L, Joshi R, Meng R, Seeholzer SH, Choi JK, Koretzky G, Marks MS, Abrams CS. Loss of PIKfyve in platelets causes a lysosomal disease leading to inflammation and thrombosis in mice. Nat Commun 5: 4691, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mize CW, Koehler KJ, Compton ME. Statistical considerations for in vitro research. II. Data to presentation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 35: 122–126, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morishita H, Eguchi S, Kimura H, Sasaki J, Sakamaki Y, Robinson ML, Sasaki T, Mizushima N. Deletion of autophagy-related 5 (Atg5) and Pik3c3 genes in the lens causes cataract independent of programmed organelle degradation. J Biol Chem 288: 11436–11447, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morissette G, Moreau E, RCG, Marceau F. Massive cell vacuolization induced by organic amines such as procainamide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310: 395–406, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Overmeyer JH, Young AM, Bhanot H, Maltese WA. A chalcone-related small molecule that induces methuosis, a novel form of non-apoptotic cell death, in glioblastoma cells. Mol Cancer 10: 69, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papini E, Bugnoli M, De Bernard M, Figura N, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits Helicobacter pylori-induced vacuolization of HeLa cells. Mol Microbiol 7: 323–327, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Posor Y, Eichhorn-Gruenig M, Puchkov D, Schoneberg J, Ullrich A, Lampe A, Muller R, Zarbakhsh S, Gulluni F, Hirsch E, Krauss M, Schultz C, Schmoranzer J, Noe F, Haucke V. Spatiotemporal control of endocytosis by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Nature 499: 233–237, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutherford AC, Traer C, Wassmer T, Pattni K, Bujny MV, Carlton JG, Stenmark H, Cullen PJ. The mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase (PIKfyve) regulates endosome-to-TGN retrograde transport. J Cell Sci 119: 3944–3957, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49a.Saveanu L, Lotersztajn S. New pieces in the complex puzzle of aberrant vacuolation. Focus on “Active vacuolar H+ ATPase and functional cycle of Rab5 are required for the vacuolation defect triggered by PtdIns(3,5)P2 loss under PIKfyve or Vps34 deficiency.” Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00215.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Filios C, Delvecchio K, Shisheva A. Functional dissociation between PIKfyve-synthesized PtdIns5P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 by means of the PIKfyve inhibitor YM201636. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C436–C446, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Fu Z, Ijuin T, Gruenberg J, Takenawa T, Shisheva A. Core protein machinery for mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate synthesis and turnover that regulates the progression of endosomal transport. Novel Sac phosphatase joins the ArPIKfyve-PIKfyve complex. J Biol Chem 282: 23878–23891, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Shisheva A. PIKfyve, a mammalian ortholog of yeast Fab1p lipid kinase, synthesizes 5-phosphoinositides. Effect of insulin. J Biol Chem 274: 21589–21597, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schink KO, Raiborg C, Stenmark H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, a lipid that regulates membrane dynamics, protein sorting and cell signalling. Bioessays 35: 900–912, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott CC, Vacca F, Gruenberg J. Endosome maturation, transport and functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 31: 2–10, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shisheva A. Phosphoinositides in insulin action on GLUT4 dynamics: not just PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E536–E544, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shisheva A. PIKfyve and its lipid products in health and in sickness. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 362: 127–162, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shisheva A. PIKfyve: Partners, significance, debates and paradoxes. Cell Biol Int 32: 591–604, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shisheva A. PtdIns5P: news and views of its appearance, disappearance and deeds. Arch Biochem Biophys 538: 171–180, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shisheva A, Sbrissa D, Ikonomov O. Plentiful PtdIns5P from scanty PtdIns(3,5)P2 or from ample PtdIns? PIKfyve-dependent models: evidence and speculation. Bioessays 37: 267–277, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stenmark H, Parton RG, Steele-Mortimer O, Lutcke A, Gruenberg J, Zerial M. Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J 13: 1287–1296, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takasuga S, Horie Y, Sasaki J, Sun-Wada GH, Kawamura N, Iizuka R, Mizuno K, Eguchi S, Kofuji S, Kimura H, Yamazaki M, Horie C, Odanaga E, Sato Y, Chida S, Kontani K, Harada A, Katada T, Suzuki A, Wada Y, Ohnishi H, Sasaki T. Critical roles of type III phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase in murine embryonic visceral endoderm and adult intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1726–1731, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Umata T, Moriyama Y, Futai M, Mekada E. The cytotoxic action of diphtheria toxin and its degradation in intact Vero cells are inhibited by bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase. J Biol Chem 265: 21940–21945, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vanhaesebroeck B, Stephens L, Hawkins P. PI3K signalling: the path to discovery and understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 195–203, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Venkatareddy M, Verma R, Kalinowski A, Patel SR, Shisheva A, Garg P. Distinct requirements for vacuolar protein sorting 34 downstream effector phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase in podocytes versus proximal tubular cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2702–2719, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou X, Wang L, Hasegawa H, Amin P, Han BX, Kaneko S, He Y, Wang F. Deletion of PIK3C3/Vps34 in sensory neurons causes rapid neurodegeneration by disrupting the endosomal but not the autophagic pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 9424–9429, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]