Abstract

Conjunctival integrity and preservation is indispensable for vision. The self-renewing capacity of conjunctival cells controls conjunctival homeostasis and regeneration; however, the source of conjunctival self-renewal and the underlying mechanism is currently unclear. Here, we characterize the biochemical phenotype and proliferative potential of conjunctival epithelial cells in adult mouse by detecting proliferation-related signatures and conducting clonal analysis. Further, we show that transcription factor 7-like 2 (T-cell-specific transcription factor 4), a DNA binding protein expressed in multiple types of adult stem cells, is highly correlated with proliferative signatures in basal conjunctival epithelia. Clonal studies demonstrated that Transcription factor 7-like 2 (Tcf7l2) was coexpressed with p63α and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in propagative colonies. Furthermore, Tcf7l2 was actively transcribed concurrently with conjunctival epithelial proliferation in vitro. Collectively, we suggest that Tcf7l2 may be involved in maintenance of stem/progenitor cells properties of conjunctival epithelial stem/progenitor cells, and with the fornix as the optimal site to isolate highly proliferative conjunctival epithelial cells in adult mice.

Keywords: conjunctival epithelium, proliferation, Tcf7l2

all self-renewing tissues, including the conjunctiva, contain cells with the unique ability to both self-renew and differentiate into lineages of their tissue origin. Therefore, tissue self-renewal is essential for tissue homeostasis and for tissue regeneration after injury. According to The World Health Organization, 45 million people worldwide are blind (36, 41). Conjunctival homeostasis plays a critical role in maintaining acute visual acuity by protecting the ocular surface through its mucosal immune and tear-producing functions (3, 35). The conjunctiva is a mucous membrane that extends from the superior and inferior eyelid margins to the limbus, covering the majority of the ocular surface (Fig. 1, A and B). The conjunctival surface is composed of a nonkeratinized, self-renewing, pluristratified epithelium of ectodermal origin (19, 40). The conjunctival epithelium consists of conjunctival epithelial cells and interspersed goblet cells, underlain by layers of loose vascularized connective tissue, which are separated from the epithelium by a basement membrane (44).

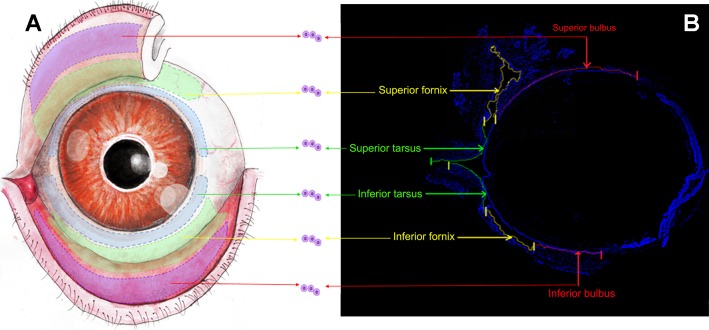

Fig. 1.

Demarcation of conjunctival regions. A: scheme of the stereotypical conjunctival epithelial architecture of adult mouse [6- to 8-wk-old mice (C57BL/6J, Harlan) of both sexes were used in all experiments]. The purple areas (red arrows) extending from the superior and inferior lid margins indicate the superior and inferior tarsus, the green curved ribbon (yellow arrows) adjacent to the bulbar conjunctiva indicates the superior and inferior fornix, and the half ring-shaped blue curve (green arrows) marks the superior and inferior bulbus. B: sagittal frozen section of mouse conjunctiva (n = 21 in 3 independent experiments). Cell nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). The superior and inferior conjunctiva formed a continuous envelope shape with each region marked and labeled with arrows. Cells and explants were obtained from the individual sections labeled in A and B. Scale bars, 500 μm.

Self-renewal, the hallmark feature of normal stem cells (34), is the process by which stem cells generate progeny identical to themselves (33). Ultimately, if a stem cell can initiate clonal growth in vitro, it can be identified as a stem cell because the colony will contain cells with larger clonal capacity (1). Holoclones arise from precursors present in stem cell-derived populations.

The balance between stem cell self-renewal and differentiation is regulated by intrinsic transcription factors and extracellular niche signals (20, 31, 39). Much progress has been made in elucidating stem cell-regulatory mechanisms (20, 31). With the study of adult stem cell biology, recurring roles of Transcription factor 7-like 2 (T-cell-specific transcription factor 4, high mobility group box transcription factor 4) are rapidly being uncovered (9, 24, 29). Transcription factor 7-like 2 (Tcf7l2) belongs to a group of T-cell-specific transcription factors family that bind to DNA through a high-mobility group domain (9). Tcf7l2 activation triggers gene transcription and may be correlated with multiple stem cell features as well as wound repair (9, 24). More recently, studies on corneal epithelial stem cells indicated that the activation and increased expression of Tcf7l2 maintain corneal epithelial stem cells in a less differentiated state (15). Nonetheless, a Tcf role in conjunctival epithelium has not been examined.

Accordingly, we have now characterized the proliferative potential of mouse conjunctival epithelial cells by a combination of cell culture, clonal analysis, and immunofluorescence. Our results indicate that, as previously described in rabbits, the conjunctival fornix contains the cells with the highest proliferative potential. Additionally, we show that Tcf7l2 may be a signature of rapidly proliferating conjunctival epithelial cells. These findings may open up new possibilities for further functional studies on the role of Tcf7l2 in the maintenance of conjunctival epithelia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dissection and isolation of primary mouse conjunctival epithelial cells.

Six- to eight-week-old mice (C57BL/6J, Harlan) of both sexes were used in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) recommendations for animal experimentation. All animal studies were approved by the International Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-Sen University (No. 2012053). Normal conjunctival epithelial tissue was mechanically dissociated at the 12 and 6 o'clock positions and immediately placed into sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The minced tissue from each eye was divided into six pieces as previously described (6) (Fig. 1, A and B): superior and inferior bulbus, fornix, and tarsus. The fornix was identified as the band running along the most posterior part of the fold at the junction of the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva. A total of six pieces was achieved from unilateral eye measuring approximately 0.5–1 mm2. There were no significant differences in the average sizes of the explants.

Mouse conjunctival epithelial cell culture.

Explant and conjunctival epithelial cell culture were performed as previously described (14). In brief, explants or conjunctival epithelial cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (GIBCO/BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 4 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 0.4 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich). Explants or cells were refed every 2 days with this medium and were grown for 7 days under routine culture conditions of 37°C (5% CO2).

Cell counting and outgrowth fold analysis.

For cell counting in the immunostaining and clonal analysis, the percentage of marker-positive cells was determined by taking representative images and directly counting the cell number under a microscope. The cell quantitation for each experiment was listed in the text or figure legends. Student's t-tests were used to calculate P values. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD). Cells were counted manually in a blinded fashion using ImageJ software (200 fields) (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). In the outgrowth measurement, outgrowth size and explant size were quantified after 7 days of culture using ImageJ software (6). The area encircled by the blue line reflects the explant size, whereas the yellow line indicates the size of the cell outgrowth area. Explant size and outgrowth size were measured with ImageJ software and fold growth was defined as outgrowth size/explant size (magnification ×40) (see Fig. 3A).

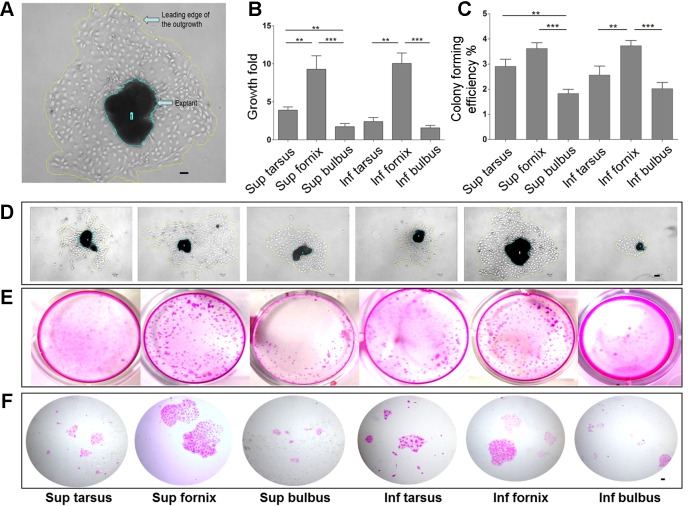

Fig. 3.

In vitro proliferative potential of conjunctival epithelial cells. A: calculation of the fold growth of conjunctival epithelial explants. B: comparison of fold growth of explants from different conjunctival epithelial locations. The bar chart displays the fold growth of cultures from the 6 conjunctival regions (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). C: clonogenic capacity of cells isolated from different conjunctival origins. The bar chart shows the colony formation efficiency of cells isolated from the 6 conjunctival regions (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). D: outgrowth of primary cultures from 6 conjunctival regions. Explant and outgrowth sizes were measured using ImageJ software (magnification: ×40). E and F: colony formation efficiency of cells isolated from different conjunctival regions with brightfield images of Rhodamine B-stained conjunctival colonies. Scale bars, 20 μm. The explant growth experiments in A, B, and D: n = 17 in 3 independent experiments; the colony formation efficiency experiment in C, E and F: n = 21 in 3 independent experiments. Sup, superior; Inf, inferior.

Clonal analysis.

Single conjunctival epithelial cells were cultivated on 100% growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD-Bioscience, San José, CA) at a concentration of 5×104 cells/cm2. Colony forming efficiency (CFE) assays, calculation of the cell number and colony size were performed as previously described (26). Conjunctival epithelial cells were plated in triplicate in a 24-well plate, and conjunctival epithelial cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F12 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; R&D Systems), 4 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.4 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich). The culture medium was changed every 48 h. Primary colony numbers, cell and colony sizes were scored after 8 days in culture. Colonies were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and stained with Rhodamine B (Sigma-Aldrich) to classify the clonal types (1, 26). Colonies were then photographed (see Fig. 3E) and further examined under a microscope (BX53, Olympus) (see Fig. 3F) (2). Digital images were analyzed for colony size and number using ImageJ.

Immunofluorescence.

For immunostaining, freshly isolated mouse conjunctival tissue specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (overnight at 4°C), embedded into OCT (Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and sectioned (5 μm thickness). Frozen conjunctival sections were fixed with methanol for 20 min at −20°C, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100-PBS for 10 min, and blocked in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Frozen conjunctival sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed, incubated with secondary antibodies for 50 min at room temperature, and counterstained with propidium iodide (PI; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The following antibodies were used: Tcf7l2 (C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), p63α (H-129, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), CK19 (EP1580Y, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), CK13 (2Q1040, Abcam), PCNA (PC10, Cell Signaling), and MUC5AC (45M1, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).For double fluorescent staining, CK19, Tcf7l2, CK13, PCNA, and p63α primary antibodies were used at the dilutions recommended by the manufacturers. Secondary Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and 555 (red) antibodies were incubated with the samples at a 1:300 dilution for 50 min. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)/antifade mountant (Invitrogen) and coverslipped. Sections were examined with a fluorescent microscope (BX-53, Olympus).

To assess the colony composition, cells were fixed on plates for 20 min in methanol at −20°C and then stained. The same fixation and staining protocol of frozen section staining was used for colony immunofluorescence. Colonies were then examined with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus).

Microscopy and image analysis.

For immunofluorescence analysis, images were taken at room temperature using the fluorochromes DAPI, Alexa Fluor 488 (green), and Alexa Fluor 555 (red). Confocal images were captured with a Zeiss Meta LSM 510 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany; software: Zen 2009; objectives: 10×/0.3; 20×/0.5; 40×1.3 oil; 63×/1.4 oil). Fluorescence images were taken with an Olympus BX-53 microscope (software: Applied Precision Software; magnifications: 20×/0.75; 10×/0.40; 40×/1.35 oil; 60×/1.42 oil). For explant proliferation studies and clonal analysis, bright-field microscopy was performed using an Olympus BX-53 microscope (software: Olympus Cell D; objectives: 10×/0.4; 20×/0.75; 40×/0.4). Cell and explant culture images were taken using an Olympus E-620 camera. Photoshop (CS6, Adobe) and ImageJ were used for further image processing. No image medium was used. For illustration purposes, images were adjusted using the level and brightness/contrast tools in Photoshop; the same adjustments were applied to every pixel in each RGB channel.

Statistical analysis.

Fold growth and CFE of different conjunctival orientations were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) q test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data are reported as means ± SD unless otherwise stated, and significance was set at P < 0.05. Error bars indicate the SD of the mean.

RESULTS

Immunophenotype and in vitro proliferative potential of conjunctival epithelial stem/progenitor cells in adult mouse.

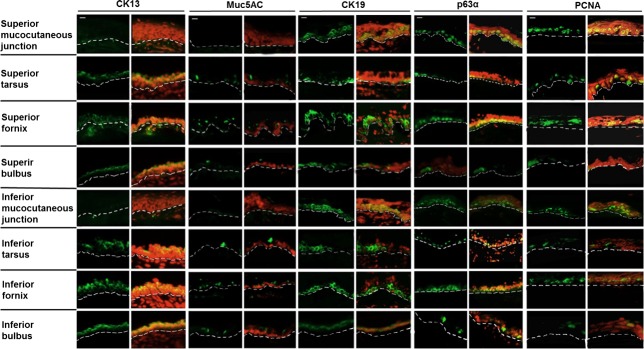

The expression profiles of the conjunctival epithelium are shown in 8 locations according to anatomical demarcations (Fig. 1, A and B). CK13, which marks stratified epithelial cells (7, 10), presented ubiquitous strong expression in the superficial conjunctival layers (Fig. 2). Goblet cells were interspersed all over the superficial layers according to goblet cell-specific protein MUC5AC expression (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the mucocutaneous junctional portion exhibited a complete absence of CK13 and MUC5AC, indicating that lid marginal cells were unlikely from conjunctival origin. CK19 [an epithelial progenitor cell marker (10)] and p63α [a putative stem cell marker (5, 11, 25)] were highly expressed in the basal and suprabasal conjunctival epithelium (Fig. 2), mostly in forniceal and mucocutaneous junctional portion. PCNA, a cell proliferation signature (18, 38), exhibited circle-shaped staining inside the nucleus ubiquitously and was expressed in the basal and suprabasal conjunctival epithelium.

Fig. 2.

Expression profile of mouse conjunctival epithelium. Identification of highly proliferative cells within mouse conjunctiva was accomplished by detecting a group of stem cell-associated proteins, including conjunctival maturation signatures markers (CK13 for conjunctival epithelial cells and MUC5AC for goblet cells), putative epithelial stem cell/precursor markers (CK19 and p63α), and a proliferative marker (PCNA). Immunostaining of frozen conjunctival sections is shown in 8 locations: superior and inferior mucocutaneous junctions; superior and inferior tarsus; superior and inferior fornix; and superior and inferior bulbus. The green color in each picture indicates cells stained with individual antibodies, and cell nuclei were visualized with PI (red). The dotted line indicates the basal membrane. n = 21 in three independent experiments. Scale bars, 50 μm.

This expression pattern in the conjunctival epithelium revealed that highly proliferative cells were dispersed deep in the basal conjunctival epithelium layers. Interestingly, the mucocutaneous junctional portion showed a complete absence of CK13 and MUC5AC, indicating that lid marginal cells were unlikely from conjunctival origin. The expression pattern was consistent with a previous study that the mucocutaneous region derives from the neck of mucocutaneous glands (11). We suggest that the most proliferative cells reside within the basal layers of forniceal conjunctival epithelium. The immunolocalizations of these molecules in conjunctival epithelia are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The differential immunolocalization of stem/progenitor cell associated and differentiation markers in mouse conjunctival epithelium

| Sup Mucocutaneous Junction |

Sup Tarsus |

Sup Fornix |

Sup Bulbus |

Inf Mucocutaneous Junction |

Inf Tarsus |

Inf Fornix |

Inf Bulbus |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular markers | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup | Bas | Sup |

| CK13 | − | − | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | +++ |

| Muc5AC | − | − | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ |

| CK19 | +++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | +++ | − | ++ | − |

| p63α | +++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | ++ | − |

| PCNA | +++ | ± | +++ | ± | +++ | ± | +++ | ± | +++ | ± | +++ | ± | +++ | ± | +++ | ± |

| Tcf7l2 | ++ | − | ++ | − | +++ | − | + | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | + | − |

The grading is based on the intensity of immunofluorescent staining: −, undetectable; ±, occasionally detectable; +, weak positive; ++, moderate positive; +++, strong positive. Bas, basal; Sup, superior; Inf, inferior.

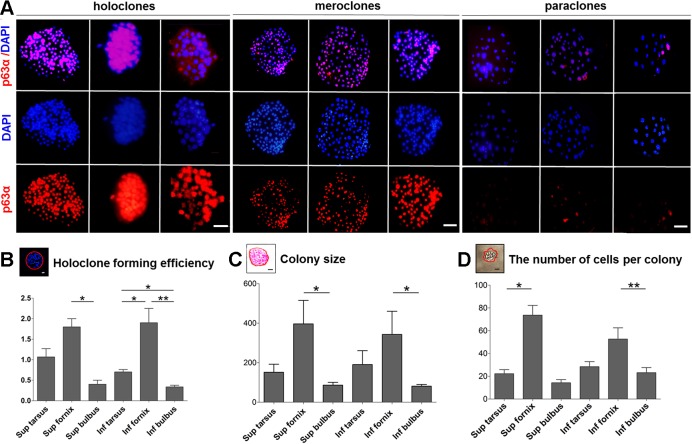

To assess whether cells isolated from the conjunctival epithelium would efficiently proliferate in vitro, we isolated single cells from 6 sites (Fig. 1, A B, and Fig. 3, A–D) and quantified their self-renewal capacity by clonal assays. Cells from the superior (CFE: 3.6 ± 0.79%) and inferior forniceal (CFE: 3.7 ± 0.46%) conjunctival epithelia raised not only the most colonies (Fig. 3, B–E) but also the highest percentage of holoclones (holoclone formation efficiency: superior fornix: 1.8 ± 0.21%, inferior fornix 1.9 ± 0.35%) (Fig. 4, A and B). In agreement, cells from the superior and inferior forniceal conjunctival origins formed colonies with the largest average size (superior fornix: 396.5 ± 256.7 μm2; inferior fornix: 343.2 ± 261.6 μm2) (Fig. 4C) and with the most cell numbers per colony (Figs. 3F and 4E). By contrast, the superior and inferior bulbal conjunctival epithelium generated the fewest colonies with relatively smaller colony size and contained fewer cells (Fig. 4D). These findings demonstrated that forniceal cells may be endowed with the highest proliferative capacity in vitro.

Fig. 4.

Identification of conjunctival epithelial colony types by p63α expression. A: colonies were isolated as described in material and methods. Immunostaining was performed on fixed colonies with p63α (red) antibody. Nuclei in the merge images were visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. Colonies were then examined under an Axiovert 200M microscope (BX-53, Olympus). Large round colonies with smooth and regular borders composed of small compact cells with scarce cytoplasm were classified as holoclones. Large colonies with irregular borders formed by cells of different sizes were classified as meroclones. Small irregular wrinkled colonies formed by dispersed large cells were classified as paraclones. B: holoclone formation efficiency from isolated single cells within different sites of the conjunctival epithelium. Error bars indicate the SD of the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. C: colony sizes generated by cells of different conjunctival epithelial origins. Error bars indicate the SD of the mean. *P < 0.05. D: number of cells contained in single colonies originating from different conjunctival regions. Error bars indicate the SD of the mean. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Colony assay in A, B, C, and D: 347 colonies were picked out, n = 21 in three independent experiments.

To further confirm the proliferative potential, we compared the explant outgrowth fold from different conjunctival epithelium locations (Fig. 3, A and D). Consistent with clonal analysis, the most effective expansion of conjunctival epithelial monolayers was achieved by tissue from the superior and inferior forniceal conjunctival epithelia (Fig. 3B).

Localization of Tcf7l2 in conjunctival epithelial stem/precursor cells.

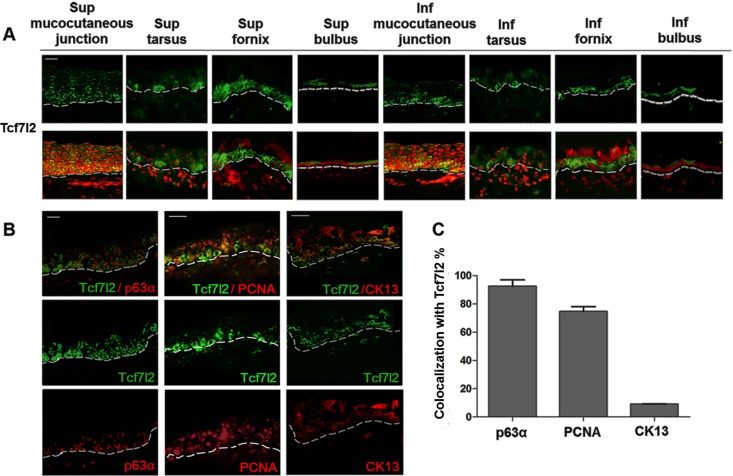

Along the ocular surface, we confirmed and extended our previous findings that T-cell-specific transcriptional factor 4 (Tcf7l2) maintained a less differentiated phenotype of corneal epithelial cells. In preliminary studies, we noted that Tcf7l2 was expressed and colocalized with p63α in the limbal area (transition zone of the peripheral cornea and bulbar conjunctiva). Moreover, Tcf7l2 translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus during expansion in vitro (15). In analogy to the regulative function of Tcf7l2 in corneal epithelial stem cells, we detected Tcf7l2 expression under physiological conditions in adult mouse conjunctival epithelium. In immunostaining, we found that Tcf7l2 were strongly positive in clusters or in interspersed single cells in the basal and suprabasal conjunctival epithelia and followed the expression pattern of the putative stem cell-related marker p63α (Fig. 5: colocalization rate, 92.6 ± 2.5%). In addition to the mucocutaneous junctional regions, the superior and inferior forniceal conjunctival epithelium contained the most Tcf7l2-positive cells. Notably, the pattern of Tcf7l2 positivity was similar to that of p63α within the conjunctival epithelium (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Tcf7l2 expression in conjunctival epithelium in adult mouse. Tcf7l2 immunostaining of frozen conjunctival sections. Tcf7l2 was visualized in green in all of the pictures (n = 16 in 3 independent experiments). A: Tcf7l2 expression in frozen conjunctival sections is shown in 8 locations, as described in the experimental procedures. Nuclei in the merge images were visualized with PI (red). B: double staining of Tcf7l2 and p63α, PCNA, or CK13. All of the antibodies, except Tcf7l2, are shown in red. C: colocalization rate of Tcf7l2 and p63α, PCNA, or CK13. Scale bars, 20 μm.

To further investigate the role of Tcf7l2 in conjunctival epithelium, we isolated and plated single cells ex vivo from superior and inferior fornix on matrigel to allow cells for in vitro proliferation and differentiation. After 7 days in culture, the conjunctival epithelial cell descendants exhibited different morphological characteristics and expression patterns to various degrees (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, A and B). Immunofluorescence demonstrated that the subcellular localization and expression of Tcf7l2 varied during propagation in vitro.

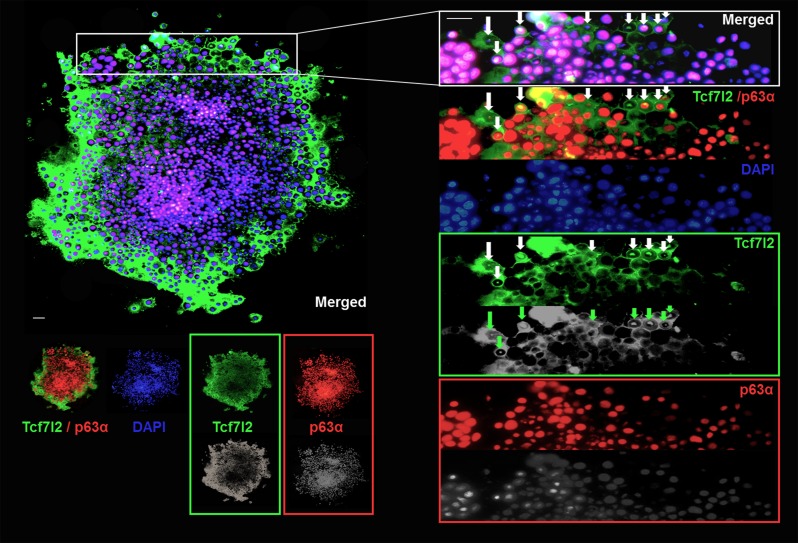

Fig. 6.

Tcf7l2 maintains conjunctival epithelial cell proliferation in vitro. After 7 days in culture, colonies were fixed and stained for Tcf7l2 (green) and p63α (red). Nuclei in the merged images were visualized with DAPI (blue). A prototypical holoclone is shown (n = 21 in 13 independent experiments). Tcf7l2 expression ubiquitously colocalized with p63α expression. Tcf7l2 presented stronger eccentric staining at further distances in the cytoplasm. Upon cultivation, Tcf7l2 translocated to the nucleus in cells near the peripheral clonal region, and the expression density of Tcf7l2 negatively correlated with that of p63α. The images illustrate the changes in Tcf7l2 and p63α expression. Tcf7l2 translocation is indicated by arrows. Scale bars, 20 μm.

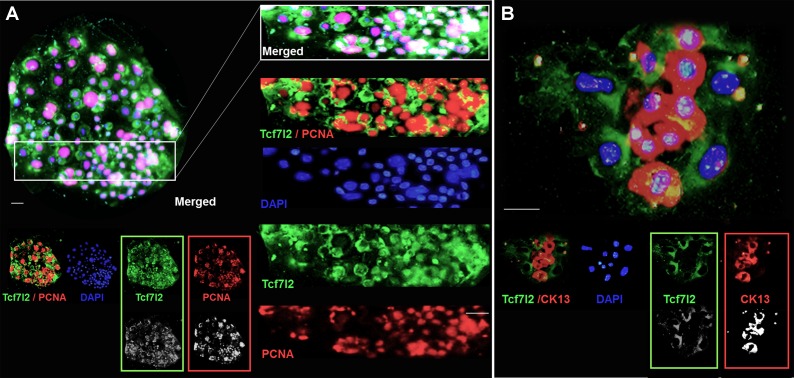

Fig. 7.

The expression pattern of Tcf7l2 varies among different types of conjunctival epithelial colonies. A: immunostaining was performed on fixed clones with Tcf7l2 (green) and PCNA (red) antibodies. Nuclei in the merge images were visualized with DAPI (blue). Colonies were then examined under a microscope (BX-53, Olympus). Stereotypic meroclones were relatively large with irregular borders formed by uneven cell size (n = 142 in 13 independent experiments). Tcf7l2 expression was positively correlated with PCNA expression. B: immunostaining of Tcf7l2 and CK13. Paraclones formed small colonies expressing the conjunctiva maturation marker CK13. Notably, Tcf7l2 expression was much lower in B than in A or Fig. 6. Furthermore, Tcf7l2 expression and CK13 expression were mutually exclusive (n = 187 in 13 independent experiments). Scale bars, 20 μm.

In holoclones (Fig. 4A), Tcf7l2 was ubiquitously colocalized with p63α (Fig. 6). Notably, in contrast to p63α, cytoplasmic Tcf7l2 showed stronger positivity with increasing eccentric distance as the peripheral area of the colony expanded. Tcf7l2 translocated into the nucleus in several cells along the clonal periphery (Fig. 6), indicating that Tcf7l2 plays a role in an initial phase of the cell transition from a high proliferative potential (high p63α) to low proliferative potential, the initial stage in the transition to the terminal differentiation stage. In meroclones (Fig. 4A), cells were loosely arranged inside the clonal area with an uneven nuclear diameter, as stained by DAPI. Tcf7l2 was coexpressed with the proliferation signature PCNA (Fig. 7A). The expression of PCNA, a ring-shaped protein that encircles DNA, is indicative of the proliferative state of cells. Intriguingly, different from the physiological state (frozen sections), Tcf7l2 expression was better correlated with PCNA expression in vitro (colocalization rate: 74.7 ± 4.3%). In paraclones (Fig. 4A), Tcf7l2 expression and mature conjunctival epithelial signature (CK13) expression were mutually exclusive (Fig. 7B). CK13, a conjunctival epithelial differentiation marker (7, 10), displayed positive expression (red) in the absence of Tcf7l2 (green) (Fig. 7B).

DISCUSSION

The conjunctiva is a bona fide self-renewing tissue that harbors cells with a high proliferative potential that control tissue homeostasis and regeneration after injury. However, the source of self-renewing cells and the underlying mechanisms involved in these processes remain largely unknown. Here, we characterize the phenotype of putative conjunctival epithelial stem/precursor cells in adult mouse. Conjunctival epithelial stem/precursor cells exhibited clonogenic and progressive propagation in vitro. Consistent with our previous observation in corneal epithelial stem cells, a similar yet different pattern was observed for conjunctival epithelial cells: T-cell-specific transcription factor 4 (Tcf7l2), a co-effecter of stem cell maintenance, may be a signature of conjunctival epithelial proliferation in adult mouse (24, 29).

The origin of conjunctival epithelial self-renewal has long been a subject of intense debate, and the nature of the self-renewal process is largely elusive (16, 23, 26, 44). Previous studies have presented conflicting evidence on the source of conjunctival self-renewal, including the mucocutaneous junction (4, 44), forniceal conjunctiva (28, 45), and bulbar conjunctiva (27), and other studies have reported universal palpebral distribution (43) or the total absence of stem cells within the conjunctiva (28).

Based on our observations, scattered or clustered stem-like cells (small, round cells with a high karyoplasmic ratio) were mostly in the basal conjunctival epithelium and occasionally in the suprabasal region by immunofluorescence. To further assess the self-renewal capacity of conjunctival epithelial cells, we assessed whether dissociated single cells functioned differently at the single-cell level by clonal analysis. We collected cells from six regions of the conjunctival epithelium according to the anatomical locations mentioned above. Cells from the superior and inferior fornix exhibited the highest colony-forming efficiency in vitro (CFE: 3.6 ± 0.79% and 3.7 ± 0.46%, respectively). Similarly, these cells from the superior and inferior fornix produced the most cells per colony and the largest average primary colony size. In previous studies, colony type classification has relied on the cell number per colony, cell morphology, and clonal appearance (19, 26). Holoclones were identified based on large colony size, smooth boundaries and more importantly, their high p63α content (1, 2). Cells from the superior and inferior fornix produced the most holoclones, indicating that the founder cells have stemness characteristics in vitro (Fig. 3B). Likewise, similar results were observed in our sequential explant culture experiments. The in vitro effective expansion of conjunctival epithelial cells may contain conjunctival epithelial stem/progenitor cells and transient amplifying cells (32). Taken together, these findings suggest that cells from the forniceal epithelium are highly proliferative and exhibit stem cell properties in colony generation, colony expansion, and proliferation. We suggest that the superior and inferior fornix is an optimal source for autologous or allogenic conjunctiva replacement.

After characterizing the expression patterns of mouse conjunctival epithelial cells, we evaluated the roles of Tcf7l2 in the self-renewal process by immunofluorescence and clonal analysis.

Remarkable advances in the understanding of external signals required for the maintenance of adult stem cell properties have occurred in recent years (8, 35). The regulation of adult stem cell proliferation ensures tissue homeostasis and regeneration after injury (30). Multiple studies have focused on the underlying mechanisms of these processes (31).

T-cell-specific transcription factor 4 (Tcf7l2), a member of DNA-binding transcriptional activators family, has been previously considered as a DNA binding protein that binds to β-catenin and activates Wnt target genes (9). Tcf7l2 is involved in establishing proliferative crypts, which are the prototypical stem cell compartments (9). Consequently, the maintenance of adult crypt proliferation is Wnt signaling-dependent, as demonstrated by deletion of Tcf7l2 (37). More importantly, in addition to functioning as a transcriptional activator, Tcf7l2 has Wnt-independent roles in lineage determination (24). Our preliminary studies revealed that Tcf7l2 maintains the properties of corneal epithelial stem cells (14, 15). The balance between conjunctival epithelial cell self-renewal and differentiation maintains conjunctival homeostasis. The roles of Tcf7l2 in maintaining homeostasis in conjunctival epithelium have not been previously identified. In agreement with our previous finding in corneal epithelium, Tcf7l2 exhibited strong positive staining in concrete clusters of basal and to a lesser extent, suprabasal cells, mostly in the superior and inferior forniceal areas. A strong correlation was found between Tcf7l2 and stemness-related marker p63α expression within conjunctival epithelium. We therefore propose that strong Tcf7l2 expression may be related to the highly proliferative potential of these cells.

To further study the roles of Tcf7l2 in the proliferation of conjunctival epithelial cells, we next isolated and cultured cells from the forniceal conjunctival epithelium. High Tcf7l2 and p63α coexpression was noted in holoclones. In holoclones, we observed that Tcf7l2 expression increased from the clonal center towards the clonal periphery and that p63α expression was attenuated outwardly. During in vitro propagation, the nuclear expression of Tcf7l2 was observed, coupled to cell proliferation. The opposite expression patterns of Tcf7l2 and p63α were coupled with nuclear Tcf7l2 expression around the clonal edges. The switch in Tcf7l2 accumulation was reported to occur in corneal epithelial stem cells during the ex vivo wound healing process, during which Tcf7l2 translocated into the nucleus mostly along the wound edge (15). Thus Tcf7l2 might correlate more to colony expansion than to colony initiation. This finding was notable and consistent with the known role of Tcf7l2 in regulating long-term cell self-renewal (24).

Expression of the conjunctival differentiation marker CK13 was absent in holoclones. The mutually exclusive expression of Tcf7l2 and CK13 in paraclones suggested that low Tcf7l2 expression might be attributed to cell differentiation. Collectively, these data shed light on the role of Tcf7l2 in modulating conjunctival epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation.

Summary.

In conclusion, our study lends support to the conjunctival epithelial self-renewal hypothesis based on the identification of cells with the highest proliferation capacity in the forniceal conjunctiva. In combination with physiological status, in vitro outgrowth proliferation studies demonstrated that the Tcf7l2 localized in putative conjunctival epithelial stem/precursor cells. Altogether, our study suggests that Tcf7l2 expression may correlate with the highly proliferative potential of conjunctival epithelial cells and serve as a potential signature of highly proliferative conjunctival epithelial cells. Tcf7l2 may be involved in maintenance of stem/progenitor cells properties of conjunctival epithelial stem/progenitor cells.

GRANTS

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81270013).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.Q. and R.L. conception and design of research; Y.Q., X.Z., S.X., and K.L. performed experiments; Y.Q., F.Z., Q.L., and X.C. analyzed data; Y.Q., X.Z., and R.L. drafted manuscript; Y.Q., X.Z., S.X., K.L., F.Z., Q.L., X.C., and R.L. approved final version of manuscript; K.L. prepared figures; R.L. edited and revised manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrandon Y, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 2302–2306, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Iorio E, Barbaro V, Ruzza A, Ponzin D, Pellegrini G, De Luca M. Isoforms of DeltaNp63 and the migration of ocular limbal cells in human corneal regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9523–9528, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dilly PN. Structure and function of the tear film. Adv Exp Med Biol 350: 239–247, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donisi PM, Rama P, Fasolo A, Ponzin D. Analysis of limbal stem cell deficiency by corneal impression cytology. Cornea 22: 533–538, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dziasko MA, Tuft SJ, Daniels JT. Limbal melanocytes support limbal epithelial stem cells in 2D and 3D microenvironments. Exp Eye Res 138: 70–79, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eidet JR, Fostad IG, Shatos MA, Utheim TP, Utheim ØA, Raeder S, Dartt DA. Effect of biopsy location and size on proliferative capacity of ex vivo expanded conjunctival tissue. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 2897–2903, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper M. Heterogeneity in the immunolocalization of cytokeratin specific monoclonal antibodies in the rat eye: evaluation of unusual epithelial tissue entities. Histochemistry 95: 613–620, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessenbrock K, Dijkgraaf GJ, Lawson DA, Littlepage LE, Shahi P, Pieper U, Werb Z. A role for matrix metalloproteinases in regulating mammary stem cell function via the Wnt signaling pathway. Cell Stem Cell 13: 300–313, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, van Donselaar E, Huls G, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet 19: 379–383, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krenzer KL, Freddo TF. Cytokeratin expression in normal human bulbar conjunctiva obtained by impression cytology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38: 142–152, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavker RM, Treet J, Sun TT. Stem cells of the meibomian gland may play a role in the mucocutaneous junctional epithelium (MCJ) of the eyelid. Ocul Surf 3, Suppl 1: S85, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavker RM, Sun TT. Epithelial stem cells: the eye provides a vision. Eye 17: 937–942, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavker RM, Wei ZG, Sun TT. Phorbol ester preferentially stimulates mouse fornical conjunctival and limbal epithelial cells to proliferate in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39: 301–307, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu R, Bian F, Zhang X, Qi H, Chuang EY, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. The β-catenin/Tcf4/survivin signaling maintains a less differentiated phenotype and high proliferative capacity of human corneal epithelial progenitor cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 43: 751–759, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu R, Qu Y, Ge J, Zhang L, Su Z, Pflugfelder S, Li DQ. Transcription factor TCF4 maintains the properties of human corneal epithelial stem cells. Stem Cells 30: 753–761, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majo F, Rochat A, Nicolas M, Jaoude GA, Barrandon Y. Oligopotent stem cells are distributed throughout the mammalian ocular surface. Nature 456: 250–254, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massie I, Levis HJ, Daniels JT. Response of human limbal epithelial cells to wounding on 3D RAFT tissue equivalents: effect of airlifting and human limbal fibroblasts. Exp Eye Res 127: 196–205, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moldovan GL, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell 129: 665–679, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore CP, Wilsman NJ, Nordheim EV, Majors LJ, Collier LL. Density and distribution of canine conjunctival goblet cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28: 1925–1932, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison SJ, Kimble J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature 441: 1068–1074, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison SJ, Shah NM, Anderson DJ. Regulatory mechanisms in stem cell biology. Cell 88: 287–298, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison SJ, Sp radling AC. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 132: 598–611, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagasaki T, Zhao J. Uniform distribution of epithelial stem cells in the bulbar conjunctiva. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46: 126–132, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen H, Merrill BJ, Polak L, Nikolova M, Rendl M, Shaver TM, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Tcf3 and Tcf4 are essential for long-term homeostasis of skin epithelia. Nat Genet 41: 1068–1075, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, Martinell E, Fantozzi I, Bondanza S, Ponzin D, McKeon F, De Luca M. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 3156–3161, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellegrini G, Golisano O, Paterna P, Lambiase A, Bonini S, Rama P, De Luca M. Location and clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated progeny in the human ocular surface. J Cell Biol 145: 769–782, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi H, Chuang EY, Yoon KC, de Paiva CS, Shine HD, Jones DB, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Patterned expression of neurotrophic factors and receptors in human limbal and corneal regions. Mol Vis 13: 1934–1941, 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi H, Zheng X, Yuan X, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Potential localization of putative stem/progenitor cells in human bulbar conjunctival epithelium. J Cell Physiol 225: 180–185, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravindranath A, Yuen HF, Chan KK, Grills C, Fennell DA, Lappin TR, El-Tanani M. Wnt-β-catenin-Tcf-4 signalling-modulated invasiveness is dependent on osteopontin expression in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 105: 542–551, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature 441: 1075–1079, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroeder T. Imaging stem-cell-driven regeneration in mammals. Nature 453: 345–351, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selver OB, Barash A, Ahmed M, Wolosin JM. ABCG2-dependent dye exclusion activity and clonal potential in epithelial cells continuously growing for 1 month from limbal explants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 5 2: 4330–4337, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA, Till JE. The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies. J Cell Physiol 62: 327–336, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simons BD, Clevers H. Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell 145: 851–862, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanioka H, Kawasaki S, Yamasaki K, Ang LP, Koizumi N, Nakamura T, Yokoi N, Komuro A, Inatomi T, Kinoshita S. Establishment of a cultivated human conjunctival epithelium as an alternative tissue source for autologous corneal epithelial transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 3820–3827, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagers AJ. The stem cell niche in regenerative medicine. Cell Stem Cell 10: 362–369, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitcher JP, Srinivasan M, Upadhyay MP. Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ 79: 214–221, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vauclair S, Majo F, Durham AD, Ghyselinck NB, Barrandon Y, Radtke F. Corneal epithelial cell fate is maintained during repair by Notch1 signaling via the regulation of vitamin A metabolism. Dev Cell 13: 242–253, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Es JH, Haegebarth A, Kujala P, Itzkovitz S, Koo BK, Boj SF, Korving J, van den Born M, van Oudenaarden A, Robine S, Clevers H. A critical role for the Wnt effector Tcf4 in adult intestinal homeostatic self-renewal. Mol Cell Biol 32: 1918–1927, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vivona JB, Kelman Z. The diverse spectrum of sliding clamp interacting proteins. FEBS Lett 546: 167–172, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagoner MD. Chemical injuries of the eye: current concepts in pathophysiology and therapy. Surv Ophthalmol 41: 275–313, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei ZG, Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Label-retaining cells are preferentially located in fornical epithelium: implications on conjunctival epithelial homeostasis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36: 236–246, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei ZG, Lin T, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Clonal analysis of the in vivo differentiation potential of keratinocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38, 753–761, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei ZG, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Rabbit conjunctival and corneal epithelial cells belong to two separate lineages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37: 523–533, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wirtschafter JD, Ketcham JM, Weinstock RJ, Tabesh T, McLoon LK. Mucocutaneous junction as the major source of replacement palpebral conjunctival epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40: 3138–3146, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]