Abstract

5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is activated as a consequence of lipolysis and has been shown to play a role in regulation of adipose tissue mitochondrial content. Conversely, the inhibition of lipolysis has been reported to potentiate the induction of protein kinase A (PKA)-targeted genes involved in the regulation of oxidative metabolism. The purpose of the current study was to address these apparent discrepancies and to more fully examine the relationship between lipolysis, AMPK, and the β-adrenergic-mediated regulation of gene expression. In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, the adipose tissue triglyceride lipase (ATGL) inhibitor ATGListatin attenuated the Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK by a β3-adrenergic agonist (CL 316,243) independent of changes in PKA signaling. Similarly, CL 316,243-induced increases in the Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK were reduced in adipose tissue from whole body ATGL-deficient mice. Despite reductions in the activation of AMPK, the induction of PKA-targeted genes was intact or, in some cases, increased. Similarly, markers of mitochondrial content and respiration were increased in adipose tissue from ATGL knockout mice independent of changes in the Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK. Taken together, our data provide evidence that AMPK is not required for the regulation of adipose tissue oxidative capacity in conditions of reduced fatty acid release.

Keywords: 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase, white adipose tissue, lipolysis, mouse, adipose tissue triglyceride lipase, mitochondria

adipose tissue is an active metabolic organ that is intimately involved in the regulation of whole body glucose and lipid metabolism (26). Lipolysis is the primary function of adipose tissue, and the released fatty acids are important metabolic substrates, particularly in conditions of limited nutrient availability, such as fasting or prolonged exercise. Adipose tissue lipolysis is mediated through the sequential removal of fatty acids from the glycerol backbone of triacylglycerol by adipose tissue triglyceride lipase (ATGL), hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), and monoglyceride lipase (21), respectively. After lipolysis, the liberated fatty acids are oxidized in mitochondria within the adipocyte, released into the circulation to be used by peripheral tissues, or reesterified to triacylglycerol (35). Absolute rates of fatty acid reesterification increase in proportion to lipolysis (31), and the reesterification of fatty acids has been reported to be the largest consumer of ATP in adipocytes (25). It has been demonstrated that β-adrenergic stimulation activates the energy-sensing enzyme 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in adipose tissue (11) and isolated adipocytes (7) and that attenuation of fatty acid release or reesterification can blunt the activation of AMPK in fat cells (7).

AMPK is a ubiquitously expressed enzyme that has been extensively examined in skeletal muscle for its roles in the regulation of fatty acid oxidation (19), glucose transport (20), insulin sensitivity (10), and mitochondrial biogenesis (12), among others. While AMPK has been less studied in adipose tissue, accumulating evidence suggests that AMPK could be involved in the regulation of adipose tissue mitochondrial enzyme content. For instance, reductions in adipose tissue mitochondrial proteins are associated with decreases in AMPK content and activity in aged mice, perhaps secondary to reductions in lipolysis and fatty acid reesterification (17). Additionally, exercise training-induced increases in fatty acid oxidation and the protein content of the transcriptional coactivator and master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) are accompanied by increases in Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK in rat adipocytes (38). Furthermore, long-term treatment with the nonspecific AMPK agonist 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) leads to increased expression of mitochondrial genes in rat adipocytes in conjunction with increased expression of enzymes involved in lipolysis and fatty acid reesterification (4). Lastly, mitochondrial proteins are reduced, and the ability of the β3-adrenergic agonist CL 316,243 to induce PGC-1α is attenuated in adipose tissue from AMPKβ1 knockout (KO) mice (33).

While the above-mentioned findings provide evidence that lipolysis and, presumably, by extension, AMPK are important signals that can increase adipose tissue oxidative capacity, recent work has indirectly challenged this view. Mottillo and Granneman (18) showed that acute treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with CL 316,243 increased the expression of PKA-targeted genes, including PGC-1α, uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1), and neuron-derived orphan receptor 1 (NOR1), and that reducing fatty acid release via the pharmacological inhibition of HSL or knockdown of ATGL potentiated the expression of these genes. They further demonstrated that the inhibition of HSL led to a greater induction of mitochondrial enzyme expression in white adipose tissue following prolonged (5 days) treatment with CL 316,243. Unfortunately, indexes of AMPK signaling were not reported in this investigation.

These recent findings are difficult to reconcile with the AMPK literature, as decreasing fatty acid release would be expected to reduce the activation of AMPK, either secondary to decreases in fatty acid reesterification (7) or, perhaps, as has been reported in muscle cells (36), through a diminished ability of fatty acids to directly activate AMPK. In turn, reductions in fatty acid release would be hypothesized to inhibit, not potentiate, the induction of oxidative genes. Viewed together, these findings would question the role of lipolysis in activating AMPK signaling and/or regulating adipose tissue oxidative capacity. The purpose of the current investigation was to reexamine the role of lipolysis in activating AMPK and controlling the regulation of genes involved in oxidative metabolism. To accomplish this, we attenuated CL 316,243-mediated lipolysis using the recently characterized ATGL inhibitor ATGListatin (16) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and complemented these experiments in vivo using ATGL KO mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Reagents, molecular weight marker, and nitrocellulose membranes for SDS-PAGE were purchased from Bio-Rad (Mississauga, ON, Canada); antibodies against AMPKα (catalog no. 2532), Thr172 phosphorylated AMPKα (catalog no. 2535), Thr202/Tyr204 phosphorylated ERK1/2 (catalog no. 9101), ERK1/2 (catalog no. 9102), Ser660 phosphorylated HSL (catalog no. 4126), Ser563 phosphorylated HSL (catalog no. 4139), Ser565 phosphorylated HSL (catalog no. 4137), HSL (catalog no. 4107), Thr308 phosphorylated AKT (catalog no. 9275), Ser473 phosphorylated AKT (catalog no. 9271), AKT (catalog no. 9272), acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC; catalog no. 3676), Ser79 phosphorylated ACC (catalog no. 3661), and ATGL (catalog no. 2439) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); ECL Plus was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Arlington Heights, IL); TaqMan gene expression assays for UCP-1 (catalog no. Mm01244861_m1), PGC-1α (catalog no. Mm01208835_m1), NOR1 (catalog no. Mm00450071_g1), and GAPDH (catalog no. 4352339E) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Burlington, ON, Canada); reagents for measurement of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs) were from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA); cell culture reagents, including Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution, and penicillin-streptomycin, were from Hyclone Laboratories (Logan, UT); and murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma.

Animals.

Nine- to 10-wk-old male wild-type (WT, C57BL6/J) and ATGL KO (B6;129P2-Pnpla2tm1Rze/J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in individual cages, with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and ad libitum access to water and standard rodent chow. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Guelph Animal Care Committee and followed Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines.

Glucose tolerance tests.

After a 5-h fast, mice underwent an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test. Mice were injected with glucose (2 g/kg body wt ip), and blood glucose was assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 90, and 120 min postinjection by tail vein sampling using a hand-held glucometer (Freestyle Lite, Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA). Changes in glucose over time were plotted, and the area under the curve was calculated.

Acute insulin treatment.

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (5 mg/100 g body wt ip), and epididymal adipose tissue was removed from the left side of the animal. The “pre” samples, in addition to being used to measure AKT phosphorylation, were used to determine mitochondrial marker proteins, PKA and AMPK signaling, and adipose tissue respiration. Mice were then injected with a weight-adjusted bolus of insulin (10 U/kg body wt ip), and the contralateral fat depots were harvested 15 min later.

Acute CL 316,243 treatment.

Mice were injected with a weight-adjusted bolus of the β3-adrenergic agonist CL 316,243 (1 mg/kg body wt ip). At 30 min postinjection, mice were anesthetized and adipose tissue was harvested.

Cell culture experiments.

3T3-L1 adipocytes were cultured in 5% CO2 and 100% humidity at 37°C. Cells were maintained in basic medium, which consisted of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 5% heat-inactivated FBS. ATGListatin was diluted in DMSO and CL 316,243 was diluted in water to create 10 mM stock solutions. Final working concentrations of 10 μM ATGListatin and CL 316,243 were used in all adipocyte experiments. The concentration of ATGListatin was selected on the basis of dose-response experiments to identify the dose that maximized the inhibition of fatty acid release while avoiding cell toxicity. Cells were seeded at a density of 6.0 × 104 cells per well in six-well plates. Differentiation was induced at day 0 (i.e., 2 days after confluence) with a standardized differentiation cocktail consisting of IBMX (0.5 mM), dexamethasone (1 μM), and human insulin (5 μg/ml) in basic medium. After 3 days, differentiation medium was removed, and for the duration of the experiment, cells were cultured in maintenance medium, which consisted of basic medium supplemented with human insulin (5 μg/ml). Maintenance medium was changed every 2 days. On day 9, maintenance medium was removed, and serum-free maintenance medium with 2% BSA was added for ∼12 h. On day 10, fresh serum-free maintenance medium containing 2% BSA and either ATGListatin (10 μM) or DMSO (i.e., the control condition) was added for 8 h. After 8 h, CL 316,243 (10 μM) was added for an additional 2 h. After a total of 10 h of treatment, the medium was collected and the cells were lysed for RNA and protein analyses. All sample extractions were performed on day 10. The aforementioned experiments were replicated several times at different passage numbers to ensure that results were not due to passage number. A total of six technical replicates were collected per treatment condition.

Total RNA and protein were extracted from adipocytes using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and a modified acetone precipitation protocol, as previously described (24). Briefly, after samples were spun through an RNeasy spin column, four parts acetone was added to the flow-through. The column was retained for standard RNA extraction, and the flow-through was incubated for ≥30 min at −20°C before centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The protein pellet was dried and resuspended in 10% SDS. Medium, RNA, and protein were stored at −80°C before all analyses.

Western blotting.

Protein was extracted from adipose tissue or adipocytes and quantified as described previously (2, 23). Equal amounts of protein were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were stained with Ponceau S to visualize equal loading, blocked with 5% powdered nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h, and then incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies. On the following day, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories) diluted in TBST-1% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminesence and subsequently quantified by densitometry using a FluorChem HD imaging system (Alpha Innotech, Santa Clara, CA). The phosphorylated signal was expressed relative to total protein, and mitochondrial protein content was expressed relative to β-actin.

Real-time RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from adipose tissue (2) or adipocytes (22), as we have described in detail previously (2, 22). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase, dNTP, and oligo(dT). Real-time PCR was employed to assess changes in the mRNA expression of Pgc-1α, Ucp-1, and Nor-1 using a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosytems), as described previously (2). Gapdh was used as an endogenous control, and relative differences between groups were determined using the cycle threshold (2−ΔΔCT) method (14).

Adipose tissue respiration.

High-resolution O2 consumption measurements were conducted in 2 ml of MiRO5 using the Oxygraph-2k (OROBOROS Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria), as described previously (32). Approximately 40–50 mg of epididymal adipose tissue were removed from WT and ATGL KO mice, minced with scissors in MiRO5 (∼30 s), quickly weighed, and then placed in an Oxygraph-2k reaction chamber. Samples were incubated in the chamber during stirring at 750 rpm (37°C) for ∼10 min before initiation of the respirometric protocols. Pyruvate (5 mM) and malate (2 mM) were added as complex I substrates (state 2 respiration), and submaximal ADP (100 μM, 500 μM, and 1 mM) was titrated. All experiments were completed before O2 concentration in the medium reached 100 μM, which is above the threshold of O2 limitation we have observed for state 3 respiration in adipose tissue (∼60–80 μM; unpublished observations). Polarographic O2 was measured in 2-s intervals, with the rate of respiration derived from 40 data points, and expressed as picomoles per second per microgram of protein.

Determination of NEFA and glycerol concentrations.

NEFA and glycerol concentrations in the culture medium were determined using commercially available kits, as we have described in detail previously (15).

Statistical analysis.

Values are means ± SE. Differences between two groups were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test or ANOVA followed by least significant difference post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Inhibition of lipolysis attenuates the activation of AMPK, but not the induction of PKA-targeted genes, in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

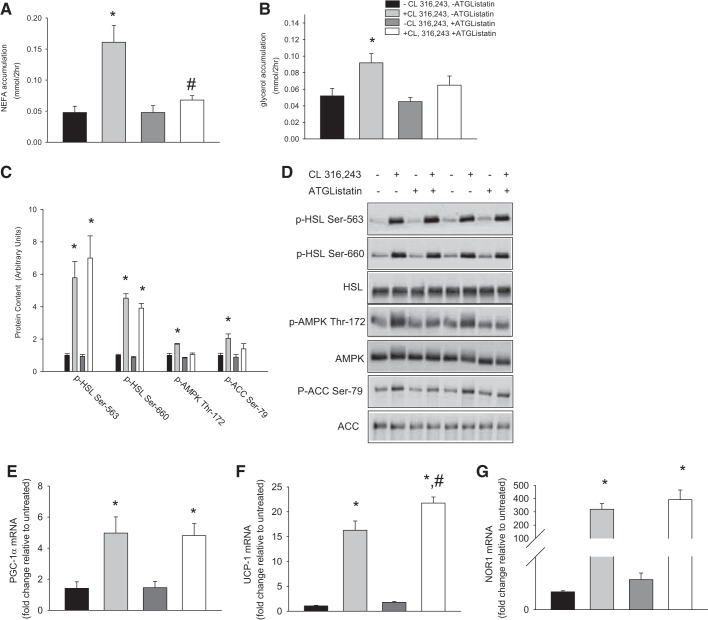

Previous work suggested that β-adrenergic-mediated activation of AMPK in adipocytes occurs secondary to the release of fatty acids (7). To examine this relationship, we treated 3T3-L1 adipocytes with the recently characterized ATGL inhibitor ATGListatin (16) and assessed alterations in lipolysis by measuring the accumulation of fatty acids and glycerol in culture medium. These end points, while not exact measures of lipolytic flux, are widely used in studies examining the regulation of adipocyte metabolism (3, 7, 18) and can be used as an index of lipolysis (39). As shown in Fig. 1, ATGListatin prevented CL 316,243-mediated increases in fatty acid and glycerol accumulation in the media following stimulation with the β3-adrenergic agonist CL 316,243. There were no differences in the NEFA-to-glycerol ratio between ATGListatin- and vehicle-treated cultures in the absence (1.27 ± 0.46 and 1.23 ± 0.36 with vehicle and ATGListatin, respectively) or presence (1.93 ± 0.43 and 1.25 ± 0.26 with vehicle and ATGListatin, respectively) of CL 316,243. The attenuation in indexes of lipolysis was not secondary to reductions in PKA signaling, as phosphorylation of HSL on the PKA-sensitive Ser563 and Ser660 sites (Fig. 1, B and C) was intact in ATGListatin-treated cells. Total HSL remained unchanged. CL 316,243 treatment increased the phosphorylation of AMPK on Thr172 and its downstream substrate ACC; however, these increases were absent in cells treated with ATGListatin (Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of lipolysis attenuates 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling, but not induction of PKA-targeted genes, in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with the adipose tissue triglyceride lipase (ATGL) inhibitor ATGListatin (10 μM) for 8 h prior to 2 h of treatment with the β3-adrenergic agonist CL 316,243. Changes in fatty acid release (A), glycerol release (B), phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), AMPK, and acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC; C and D), and mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α, E), uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1, F), and neuron-derived orphan receptor 1 (NOR1, G) were determined. Values are means ± SE for 6 technical replicates per group. *P < 0.05, CL 316,243 vs. −CL 316,243, −ATGListatin. #P < 0.05, CL 316,243 vs. +CL 316,243, +ATGListatin.

We previously provided evidence for a role of AMPK in mediating, in part, the effects of CL 316,243 on the induction of PGC-1α (33). Given this and the fact that AMPK signaling was attenuated in conditions of reduced lipolysis, we next examined the effects of ATGListatin on genes that are induced following β-adrenergic receptor activation. Our focus was on genes that are rapidly increased by β3-adrenergic agonists, including PGC-1α, UCP-1, and NOR1 (18). CL 316,243-mediated increases in PGC-1α and NOR1 were similar (Fig. 1, E and G), while the induction of UCP-1 was potentiated (Fig. 1F) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with ATGListatin compared with those treated with CL 316,243 alone.

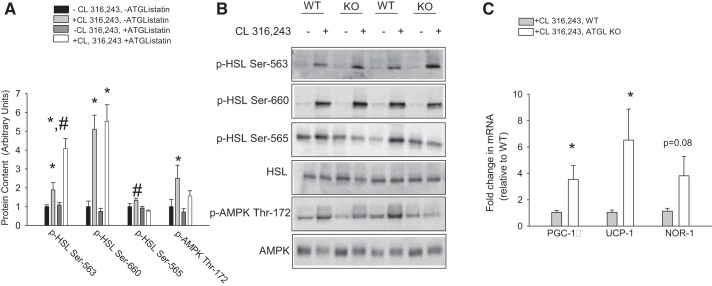

CL 316,243-mediated activation of AMPK signaling, but not the induction of PKA-targeted genes, is attenuated in adipose tissue from ATGL KO mice.

Our data in 3T3-L1 adipocytes provide evidence that the inhibition of fatty acid release prevents the CL 316,243-mediated activation of AMPK; yet, surprisingly, this is not associated with an abrogation of CL 316,243-mediated increases in the induction of PGC-1α, UCP-1, and NOR1. To extend this to an in vivo model, we examined these responses in whole body ATGL KO mice. ATGL KO mice develop marked cardiac fibrosis and triacylglycerol accumulation, which are associated with cardiac dysfunction and premature death (starting at ∼14 wk of age) (8). Given their short lifespan, mice were studied at 9–10 wk of age. To examine the in vivo relationship between markers of lipolysis and AMPK, mice were injected with CL 316,243 (1.0 mg/kg body wt) or an equivalent volume of sterile saline and tissue was harvested 30 min later. CL 316,243 increased plasma free fatty acids ∼2.5-fold in WT mice, while this increase was completely absent in ATGL KO mice (2.45 ± 0.22 and 1.14 ± 0.09-fold increase in WT and ATGL KO mice, respectively, P < 0.05). These data have been reported previously as absolute values in these same mice (15). Under CL 316,243-stimulated conditions, serum glycerol concentrations were reduced (P < 0.05) in ATGL KO compared with WT mice (0.70 ± 0.03 and 1.03 ± 0.03 mM, respectively, n = 5/group). Consistent with our results using cultured adipocytes, CL 316,243 increased Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK, while the inhibition of lipolysis attenuated this change (Fig. 2, A and B). To assess a downstream readout of AMPK signaling, we measured changes in the phosphorylation of HSL on Ser565, an AMPK phosphorylation site (6). ACC phosphorylation was not measured, as total ACC protein content was different between genotypes (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, Ser565 phosphorylation of HSL was greater in WT than ATGL KO mice under CL 316,243-stimulated conditions. The attenuated activation of AMPK was not secondary to reductions in PKA signaling, as indicated by similar CL 316,243-induced Ser660 phosphorylation of HSL between genotypes, while Ser563 phosphorylation was potentiated in ATGL KO compared with WT mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Despite reductions in Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK, the induction of PKA target genes was not reduced and, in fact, UCP-1 and PGC-1α mRNA expression under CL 316,243-treated conditions was increased in adipose tissue from ATGL KO compared with WT mice (Fig. 2C, note that we did not have tissue from saline-treated mice for mRNA analysis).

Fig. 2.

CL 316,243-mediated increases in AMPK phosphorylation, but not induction of PKA-targeted genes, are attenuated in adipose tissue from ATGL knockout (KO) mice. Wild-type (WT) and ATGL KO mice were treated with CL 316,243 or an equivalent volume of sterile saline, and adipose tissue was collected 30 min postinjection for determination of AMPK and HSL phosphorylation (A and B) and mRNA expression of PGC-1α, UCP-1, and NOR1. Values are means ± SE for 5 animals/group. *P < 0.05, CL 316,243 vs. saline in the same genotype. #P < 0.05, CL 316, 243 vs. CL 316,243 in the corresponding genotype.

Mitochondrial protein content and respiration are increased in adipose tissue from ATGL KO mice.

Lipolysis is reduced in ATGL-deficient mice (8), and we rationalized that this would be a useful model to further examine the relationship between lipolysis and the regulation of adipose tissue oxidative capacity. Specifically, we were interested in determining if chronic reductions in lipolysis would be associated with changes in AMPK and adipose tissue mitochondrial content and respiration.

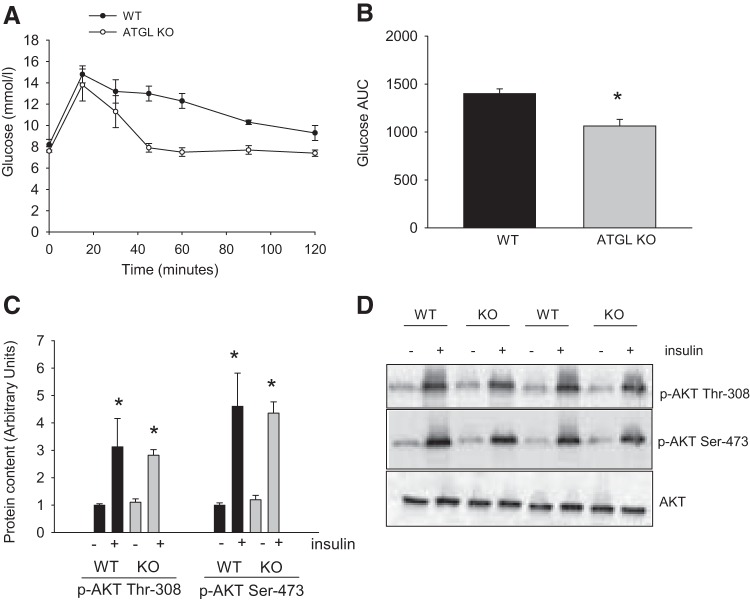

As alterations in adipose tissue mitochondrial content could be secondary to changes in whole body glucose homeostasis (29) and/or adipose tissue insulin action (9), we characterized the general metabolic phenotype of the ATGL KO mice. There were no significant differences in body weight or epididymal adipose tissue mass between genotypes (Table 1). ATGL KO mice were more glucose-tolerant than WT controls (Fig. 3, A and B); however, the insulin-induced phosphorylation of AKT on Thr308 and Ser473 was similar between genotypes (Fig. 3, C and D). As we reported previously in these same mice (15), circulating fatty acid levels were ∼40% lower in ATGL KO than WT mice (0.40 ± 0.01 vs. 0.67 ± 0.03 mmol/l).

Table 1.

Body weight and epididymal adipose tissue mass in ∼9- to 10-wk-old WT and ATGL−/− mice

| WT | ATGL−/− | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body wt, g | 24.1 ± 0.4 | 23.7 ± 0.8 | 0.69 |

| Epididymal adipose tissue mass, mg | 367 ± 12 | 408 ± 29 | 0.21 |

Values are means ± SE for 10 mice/group. WT, wild-type; ATGL, adipose tissue triglyceride lipase.

Fig. 3.

ATGL KO mice are more glucose-tolerant than WT controls, while adipose tissue insulin signaling is similar in WT and KO mice. A and B: ATGL KO and WT mice were injected intraperitoneally with a weight-adjusted bolus of glucose. A: changes in glucose over time. B: glucose area under the curve (AUC) during the glucose tolerance test. C: mice were anesthetized, and epididymal adipose tissue was removed from the left side of the animal. Mice were then injected with a weight-adjusted bolus injection of insulin (10 U/kg body wt), and the contralateral fat depots were harvested 15 min thereafter. Values are means ± SE for 5 animals per group. *P < 0.05, vs. WT control (B) and vs. −insulin (C). D: representative blots.

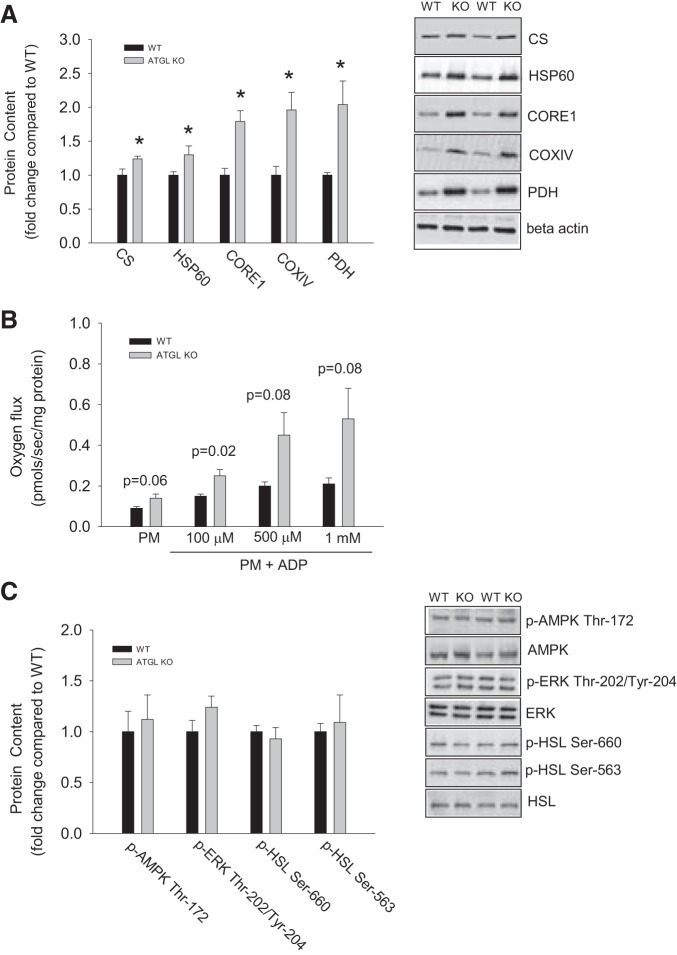

Markers of mitochondrial content such as cytochrome c oxidase IV, citrate synthase, CORE1, pyruvate dehydrogenase, and heat shock protein 60, were increased by ∼30–100% in epididymal adipose tissue from ATGL KO compared with WT mice (Fig. 4A). Similar, although less robust, differences were evident in the inguinal subcutaneous adipose tissue (data not shown). To determine if changes in mitochondrial protein content coincided with functional alterations in mitochondria, we assessed adipose tissue respiration using high-resolution O2 consumption measurements. Adipose tissue respiration was measured in the presence of pyruvate and malate (state 2 respiration) and increasing concentrations of ADP (state 3 respiration). As shown in Fig. 4B, pyruvate-, malate-, and ADP (100 μM)-supported respiration was increased in epididymal adipose tissue from ATGL KO mice. Increases in markers of mitochondrial content and respiration in adipose tissue from ATGL KO mice were not associated with differences in the Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK or in indexes of PKA signaling, such as HSL and ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Markers of mitochondrial content and respiration are increased in adipose tissue from ATGL KO mice independent of alterations in AMPK phosphorylation. A: mitochondrial proteins. COX IV, cytochrome c oxidase IV, CS, citrate synthase, HSP60, heat shock protein 60; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). B: adipose tissue respiration. PM, pyruvate + malate. C: AMPK, ERK, and HSL phosphorylation. Values are means ± SE for 10 (A and C) and 4 (B) animals per group. *P < 0.05 vs. WT.

DISCUSSION

There is a tight coupling between lipolysis and reesterification, with absolute increases in these processes mirroring each other (31). The reesterification of fatty acids is energetically demanding and links increases in lipolysis to the activation of AMPK (7), an enzyme that has been reported to control the regulation of PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis in adipose tissue (33) and the expression of UCP-1 in white adipocytes (30, 34). For this reason, it is surprising that attenuation of fatty acid release during acute β-adrenergic stimulation has been reported to potentiate the induction of PGC-1α and other PKA-targeted genes such as UCP-1 and NOR1 (18). To address these apparent discordant findings, we analyzed the relationship between indexes of lipolysis, AMPK activity, and the induction of PGC-1α, UCP-1, and NOR1 in two independent models. In both models, despite an attenuation of CL 316,243-mediated increases in Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK, increases in gene expression were intact or, in some instances, potentiated when lipolysis was reduced. Together, these findings provide evidence that, at least under conditions of reduced fatty acid release mediated by ATGL inhibition/deletion, AMPK is not required for the β-adrenergic-mediated induction of PGC-1α, UCP-1, and NOR1 gene expression. These findings help reconcile the apparent discrepant results in which the inhibition of β-adrenergic-stimulated fatty acid release was reported to attenuate the activation of AMPK (7) yet, as reported by others (18), resulted in a potentiation of CL 316,243-mediated increases in gene expression.

PKA-dependent mechanisms have been implicated in the regulation of genes involved in oxidative metabolism in adipocytes (13). It has been argued that PKA activity is increased in conditions of reduced lipolysis and that this could explain the potentiated induction of oxidative genes (18). In support of this contention, HSL phosphorylation is enhanced in adipose tissue from adipose tissue-specific ATGL-deficient mice after a 5-h fast (37). Similarly, Mottillo and Granneman (18) reported that the inhibition of fatty acid release increases β-adrenergic-stimulated increases in intracellular cAMP levels, suggesting that this could be a potential mechanism through which the suppression of lipolysis enhances the expression of PKA-targeted genes. However, indexes of PKA activation (i.e., HSL phosphorylation) were not specifically reported in this study. In contrast to these findings, in our experiments, the CL 316,243-induced phosphorylation of HSL on Ser563 and Ser660, which are PKA phosphorylation sites (1), was unaffected in conditions of reduced fatty acid release (with the exception of Ser563 phosphorylation of HSL in ATGL KO mice), suggesting that increases in PKA signaling are unlikely to explain the potentiated CL 316,243-induced increases in gene expression when fatty acid release is suppressed.

Evidence in both isolated adipose tissue and cultured adipocytes suggests that fatty acids can directly reduce the expression of genes involved in oxidative metabolism. For instance, we previously reported that palmitate treatment decreases the mRNA expression of PGC-1α and mitochondrial enzymes in cultured adipose tissue (29). Similarly, PGC-1α (5) and UCP-1 (40) are reduced in 3T3-L1 adipocytes following treatment with fatty acids. Given these results and the observation that PKA activation did not appear to be consistently elevated in conditions of reduced lipolysis, it is possible that the restriction of fatty acid release under conditions of β-adrenergic stimulation relieves a direct, PKA-independent, inhibitory effect of fatty acids on the induction of PGC-1α, UCP-1, and NOR1 expression that may mask reductions in the activation of AMPK.

Having demonstrated a disconnect between the induction of PGC-1α and the activation of AMPK, we extended these findings and examined markers of adipose tissue mitochondrial content and respiration in ATGL KO mice. A number of mitochondrial proteins were increased in the adipose tissue of ATGL KO compared with WT mice. Interestingly, despite reductions in circulating fatty acid levels, Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK was similar between genotypes. While previous studies show that free fatty acids can stimulate AMPK activity (36), these findings suggest that reductions in adipose tissue lipolysis and circulating free fatty acid levels are not sufficient to reduce AMPK phosphorylation in adipose tissue of free-moving animals in the absence of large increases in β-adrenergic stimulation.

Our findings of increased mitochondrial proteins in adipose tissue from ATGL KO mice are consistent with previous work in HSL KO mice fed a high-fat diet (28). However, as adipose tissue mitochondrial content can be influenced by the degree of adiposity (29) and given that the HSL KO mice were resistant to diet-induced obesity, differences in markers of adipose tissue mitochondrial content in HSL KO mice could be secondary to differences in adipose tissue mass; therefore, these particular findings should be interpreted cautiously. In contrast to our findings, the expression of mitochondrial genes [acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (Acox1) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B (Cpt-1b)] were reduced in adipose tissue from adipose tissue-specific ATGL KO mice (27). This discrepancy is not explained by differences in either glucose homeostasis or adipose tissue insulin signaling, as glucose tolerance was greater in both KO mouse models, likely due to reductions in circulating fatty acids (8), while AKT phosphorylation was not significantly different between genotypes in either study. Regardless of the reasons for these discrepancies, our data suggest that the lifelong suppression of lipolysis results in increases in adipose tissue mitochondrial proteins and respiration and, consistent with our cell culture work, further demonstrate a dissociation between adipose tissue mitochondrial biogenesis and AMPK, at least under conditions of reduced fatty acid release.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that inhibition of ATGL-mediated lipolysis attenuates β-adrenergic-stimulated increases in Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK while concurrently increasing the induction of PKA-targeted genes. We have further demonstrated that the lifelong deletion of ATGL results in increases in markers of mitochondrial content and respiration independent of changes in Thr172 phosphorylation of AMPK. In contrast to recent work from our laboratory using AMPKβ1−/− mice (33), the findings of the current investigation demonstrate that, at least under conditions of reduced fatty acid release, AMPK may not be essential for the regulation of adipose tissue oxidative metabolism. The results of the current study help reconcile discrepancies in the literature concerning the relationship between lipolysis, AMPK activation, and the induction of PKA target genes.

GRANTS

R. E. K. MacPherson was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Alzheimer's Society of Canada. S. Frendo-Cumbo was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Graduate Scholarship. C. G. R. Perry, D. M. Mutch, and D. C. Wright are recipients of NSERC Discovery Grants. M. J. Watt is a Senior Fellow of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. D. C. Wright is a Tier II Canada Research Chair.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.E.K.M., S.M.D., S.R., M.J.W., D.M.M., and D.C.W. developed the concept and designed the research; R.E.K.M., S.M.D., S.R., C.S., S.F.-C., L.C., and C.G.P. performed the experiments; R.E.K.M., S.M.D., S.R., C.S., S.F.-C., L.C., C.G.P., D.M.M., and D.C.W. analyzed the data; R.E.K.M., S.M.D., S.R., C.S., S.F.-C., L.C., M.J.W., C.G.P., D.M.M., and D.C.W. interpreted the results of the experiments; R.E.K.M. and D.C.W. prepared the figures; R.E.K.M., M.J.W., and D.C.W. drafted the manuscript; R.E.K.M., S.M.D., S.R., C.S., S.F.-C., L.C., M.J.W., C.G.P., D.M.M., and D.C.W. edited and revised the manuscript; R.E.K.M., S.M.D., S.R., C.S., S.F.-C., L.C., M.J.W., C.G.P., D.M.M., and D.C.W. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthonsen MW, Ronnstrand L, Wernstedt C, Degerman E, Holm C. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites in hormone-sensitive lipase that are phosphorylated in response to isoproterenol and govern activation properties in vitro. J Biol Chem 273: 215–221, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castellani L, Root-Mccaig J, Frendo-Cumbo S, Beaudoin MS, Wright DC. Exercise training protects against an acute inflammatory insult in mouse epididymal adipose tissue. J Appl Physiol 116: 1272–1280, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaidhu MP, Anthony NM, Patel P, Hawke TJ, Ceddia RB. Dysregulation of lipolysis and lipid metabolism in visceral and subcutaneous adipocytes by high-fat diet: role of ATGL, HSL, and AMPK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C961–C971, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaidhu MP, Fediuc S, Anthony NM, So M, Mirpourian M, Perry RL, Ceddia RB. Prolonged AICAR-induced AMP-kinase activation promotes energy dissipation in white adipocytes: novel mechanisms integrating HSL and ATGL. J Lipid Res 50: 704–715, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao CL, Zhu C, Zhao YP, Chen XH, Ji CB, Zhang CM, Zhu JG, Xia ZK, Tong ML, Guo XR. Mitochondrial dysfunction is induced by high levels of glucose and free fatty acids in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 320: 25–33, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garton AJ, Campbell DG, Carling D, Hardie DG, Colbran RJ, Yeaman SJ. Phosphorylation of bovine hormone-sensitive lipase by the AMP-activated protein kinase. A possible antilipolytic mechanism. Eur J Biochem 179: 249–254, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauthier MS, Miyoshi H, Souza SC, Cacicedo JM, Saha AK, Greenberg AS, Ruderman NB. AMP-activated protein kinase is activated as a consequence of lipolysis in the adipocyte: potential mechanism and physiological relevance. J Biol Chem 283: 16514–16524, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haemmerle G, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Gorkiewicz G, Meyer C, Rozman J, Heldmaier G, Maier R, Theussl C, Eder S, Kratky D, Wagner EF, Klingenspor M, Hoefler G, Zechner R. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 312: 734–737, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katic M, Kennedy AR, Leykin I, Norris A, McGettrick A, Gesta S, Russell SJ, Bluher M, Maratos-Flier E, Kahn CR. Mitochondrial gene expression and increased oxidative metabolism: role in increased lifespan of fat-specific insulin receptor knock-out mice. Aging Cell 6: 827–839, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjobsted R, Treebak JT, Fentz J, Lantier L, Viollet B, Birk JB, Schjerling P, Bjornholm M, Zierath JR, Wojtaszewski JF. Prior AICAR stimulation increases insulin sensitivity in mouse skeletal muscle in an AMPK-dependent manner. Diabetes 64: 2042–2055, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh HJ, Hirshman MF, He H, Li Y, Manabe Y, Balschi JA, Goodyear LJ. Adrenaline is a critical mediator of acute exercise-induced AMP-activated protein kinase activation in adipocytes. Biochem J 403: 473–481, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lantier L, Fentz J, Mounier R, Leclerc J, Treebak JT, Pehmoller C, Sanz N, Sakakibara I, Saint-Amand E, Rimbaud S, Maire P, Marette A, Ventura-Clapier R, Ferry A, Wojtaszewski JF, Foretz M, Viollet B. AMPK controls exercise endurance, mitochondrial oxidative capacity, and skeletal muscle integrity. FASEB J 28: 3211–3224, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu D, Bordicchia M, Zhang C, Fang H, Wei W, Li JL, Guilherme A, Guntur K, Czech MP, Collins S. Activation of mTORC1 is essential for β-adrenergic stimulation of adipose browning. J Clin Invest 126: 1704–1716, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacPherson RE, Castellani L, Beaudoin MS, Wright DC. Evidence for fatty acids mediating CL 316,243-induced reductions in blood glucose in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E563–E570, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer N, Schweiger M, Romauch M, Grabner GF, Eichmann TO, Fuchs E, Ivkovic J, Heier C, Mrak I, Lass A, Hofler G, Fledelius C, Zechner R, Zimmermann R, Breinbauer R. Development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting adipose triglyceride lipase. Nat Chem Biol 9: 785–787, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mennes E, Dungan CM, Frendo-Cumbo S, Williamson DL, Wright DC. Aging-associated reductions in lipolytic and mitochondrial proteins in mouse adipose tissue are not rescued by metformin treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 1060–1068, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mottillo EP, Granneman JG. Intracellular fatty acids suppress β-adrenergic induction of PKA-targeted gene expression in white adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301: E122–E131, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill HM, Lally JS, Galic S, Thomas M, Azizi PD, Fullerton MD, Smith BK, Pulinilkunnil T, Chen Z, Samaan MC, Jorgensen SB, Dyck JR, Holloway GP, Hawke TJ, van Denderen BJ, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR. AMPK phosphorylation of ACC2 is required for skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation and insulin sensitivity in mice. Diabetologia 57: 1693–1702, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neill HM, Maarbjerg SJ, Crane JD, Jeppesen J, Jorgensen SB, Schertzer JD, Shyroka O, Kiens B, van Denderen BJ, Tarnopolsky MA, Kemp BE, Richter EA, Steinberg GR. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-β1β2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 16092–16097, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peckett AJ, Wright DC, Riddell MC. The effects of glucocorticoids on adipose tissue lipid metabolism. Metabolism 60: 1500–1510, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ralston JC, Badoud F, Cattrysse B, McNicholas PD, Mutch DM. Inhibition of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 in differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes upregulates elongase 6 and downregulates genes affecting triacylglycerol synthesis. Int J Obes (Lond) 38: 1449–1456, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ralston JC, Matravadia S, Gaudio N, Holloway GP, Mutch DM. Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of adipocyte FADS1 and FADS2 expression and function. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23: 725–728, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ralston JC, Metherel AH, Stark KD, Mutch DM. SCD1 mediates the influence of exogenous saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids in adipocytes: effects on cellular stress, inflammatory markers and fatty acid elongation. J Nutr Biochem 27: 241–248, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rognstad R, Katz J. The balance of pyridine nucleotides and ATP in adipose tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 55: 1148–1156, 1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature 444: 847–853, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoiswohl G, Stefanovic-Racic M, Menke MN, Wills RC, Surlow BA, Basantani MK, Sitnick MT, Cai L, Yazbeck CF, Stolz DB, Pulinilkunnil T, O'Doherty RM, Kershaw EE. Impact of reduced ATGL-mediated adipocyte lipolysis on obesity-associated insulin resistance and inflammation in male mice. Endocrinology 156: 3610–3624, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strom K, Hansson O, Lucas S, Nevsten P, Fernandez C, Klint C, Moverare-Skrtic S, Sundler F, Ohlsson C, Holm C. Attainment of brown adipocyte features in white adipocytes of hormone-sensitive lipase null mice. PLos One 3: e1793, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutherland LN, Capozzi LC, Turchinsky NJ, Bell RC, Wright DC. Time course of high-fat diet-induced reductions in adipose tissue mitochondrial proteins: potential mechanisms and the relationship to glucose intolerance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1076–E1083, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Than A, He HL, Chua SH, Xu D, Sun L, Leow MK, Chen P. Apelin enhances brown adipogenesis and browning of white adipocytes. J Biol Chem 290: 14679–14691, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughan M. The production and release of glycerol by adipose tissue incubated in vitro. J Biol Chem 237: 3354–3358, 1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan Z, Perry CG, Macdonald T, Chan CB, Holloway GP, Wright DC. IL-6 is not necessary for the regulation of adipose tissue mitochondrial content. PLos One 7: e51233, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wan Z, Root-McCaig J, Castellani L, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR, Wright DC. Evidence for the role of AMPK in regulating PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial proteins in mouse epididymal adipose tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22: 730–738, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Liang X, Yang Q, Fu X, Rogers CJ, Zhu M, Rodgers BD, Jiang Q, Dodson MV, Du M. Resveratrol induces brown-like adipocyte formation in white fat through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-α1. Int J Obes (Lond) 39: 967–976, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang T, Zang Y, Ling W, Corkey BE, Guo W. Metabolic partitioning of endogenous fatty acid in adipocytes. Obes Res 11: 880–887, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watt MJ, Steinberg GR, Chen ZP, Kemp BE, Febbraio MA. Fatty acids stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase and enhance fatty acid oxidation in L6 myotubes. J Physiol 574: 139–147, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu JW, Wang SP, Casavant S, Moreau A, Yang GS, Mitchell GA. Fasting energy homeostasis in mice with adipose deficiency of desnutrin/adipose triglyceride lipase. Endocrinology 153: 2198–2207, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu MV, Bikopoulos G, Hung S, Ceddia RB. Thermogenic capacity is antagonistically regulated in classical brown and white subcutaneous fat depots by high fat diet and endurance training in rats: impact on whole-body energy expenditure. J Biol Chem 289: 34129–34140, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Heckmann BL, Liu J. Studying lipolysis in adipocytes by combining siRNA knockdown and adenovirus-mediated overexpression approaches. Methods Cell Biol 116: 83–105, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao M, Guo H, Chen X. The effect of dietary fatty acids on the recruitment of brown-like adipocytes in inguinal white adipose tissue. FASEB J 26: 1016 1014, 2012. [Google Scholar]