Abstract

Sclerostin is a Wnt signalling antagonist that controls bone metabolism. Sclerostin is expressed by osteocytes and cementocytes; however, its role in the formation of dental structures remains unclear. Here, we analysed the mandibles of sclerostin knockout mice to determine the influence of sclerostin on dental structures and dimensions using histomorphometry and micro-computed tomography (μCT) imaging. μCT and histomorphometric analyses were performed on the first lower molar and its surrounding structures in mice lacking a functional sclerostin gene and in wild-type controls. μCT on six animals in each group revealed that the dimension of the basal bone as well as the coronal and apical part of alveolar part increased in the sclerostin knockout mice. No significant differences were observed for the tooth and pulp chamber volume. Descriptive histomorphometric analyses of four wild-type and three sclerostin knockout mice demonstrated an increased width of the cementum and a concomitant moderate decrease in the periodontal space width. Taken together, these results suggest that the lack of sclerostin mainly alters the bone and cementum phenotypes rather than producing abnormalities in tooth structures such as dentin.

Keywords: alveolar bone, micro-computed tomography, mouse, periodontium, sclerostin, tooth

Introduction

Sclerostin, a product of the sclerostin gene, antagonizes Wnt/β-catenin signalling.1,2 Sclerostin is a negative regulator of bone formation and is mainly secreted by osteocytes.3 Sclerosteosis (MIM 269500), a rare autosomal recessive disorder, is due to the loss of sclerostin expression.4 van Buchem Disease (OMIM 239100) is related to the lack of a distant enhancer element that drives sclerostin expression in bone.5 Both diseases are characterized by bone overgrowth, including the overgrowth of the jaw and facial bones. Heterozygous human carriers with low sclerostin levels have a normal skeletal phenotype with dense bone.6 Patients with sclerosteosis and van Buchem disease show partial anodontia, delayed tooth eruption and malocclusion.7 Moreover, van Buchem disease is associated with overgrowth of the mandibular bone, but produces no obvious changes in cementum thickness,8 although sclerostin is expressed by cementocytes.9,10 Thus, while important information has been gathered from clinical studies, the exact role of sclerostin in the formation of teeth and the surrounding periodontal structures is unclear.

Consistent with the clinical phenotype, mice lacking sclerostin have a high bone mass phenotype.11,12 Moreover, mice lacking sclerostin demonstrate accelerated fracture healing.13 These observations have led to the development of pharmacological strategies to neutralize sclerostin.14 This approach can prevent bone loss in ovariectomized rodents,15 a finding supported by a recent clinical pilot study.16 In addition, blocking sclerostin supports bone repair in preclinical models17 and implant osseointegration.18 Recently, sclerostin antibodies were shown to stimulate bone regeneration following experimental periodontitis.19 Most data on sclerostin are focused on its role in bone development, regeneration and turnover. However, the involvement of sclerostin in the development of teeth and their periodontal structures—consisting of the alveolar bone, the periodontal ligament, the cementum and the gingiva—has not been studied in this particular mouse model.

Mouse models have revealed that sclerostin is expressed during tooth development in preodontoblasts, suggesting a possible role in dentin formation.20 Another Wnt antagonist, dickkopf-1, is strongly expressed in preodontoblasts.21 Mice with the conditional stabilisation of β-catenin in the dental mesenchyme present with aberrantly increased dentin and cementum thickness.22 The absence of β-catenin leads to erupted molars lacking roots and thin incisors.23 Taken together, these data suggest that Wnt/β-catenin signalling has an impact on the formation of dental tissues. It is thus reasonable to suggest that sclerostin has a role in the development of teeth and their surrounding periodontal structures.

The aim of the study was to generate insights into how the lack of sclerostin influences dental and periodontal tissues. Here, we examined brachydont first molars, which show eruption patterns similar to human teeth, in 4-month-old sclerostin knockout mice and the corresponding wild-type mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

For this study, the first molars and lower jaws of six female sclerostin knockout and six wild-type control mice at the age of 4 months were analysed. Sclerostin knockout mice with a targeted disruption of the sclerostin coding region have been described previously. Heterozygous Sost KO offspring were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice and then interbred to generate homozygous Sost mutant mice.12 All mice were kept in cages at a temperature of 25 °C with a 12-h light–dark cycle. Mice were fed a standard rodent diet (3302; Provimi Kliba SA, Penthalaz, Switzerland) and received water ad libitum. Protocols, handling and care of the mice conformed to the Swiss federal law for animal protection under the control of the Basel-Stadt Cantonal Veterinary Office, Switzerland. We use the terminology proposed by the 1998 Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology.

Micro-computed tomography

micro-computed tomography (µCT) was performed by vivaCT75 (SCANCO Medical AG, Brüttisellen, Switzerland). The skulls were scanned at 70 kV/114 µA with a resolution of 20.5 µm and an integration time of 300 ms. The measurements were performed using Definiens Developer XD Version 2.0.0 software (Definiens, Munich, Germany). The teeth were manually classified using Amira 5.3.0 and 5.4.0 software (Visage Imaging GmbH, Berlin, Germany) followed by automatic classification of the surrounding bone. Regions of interest are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

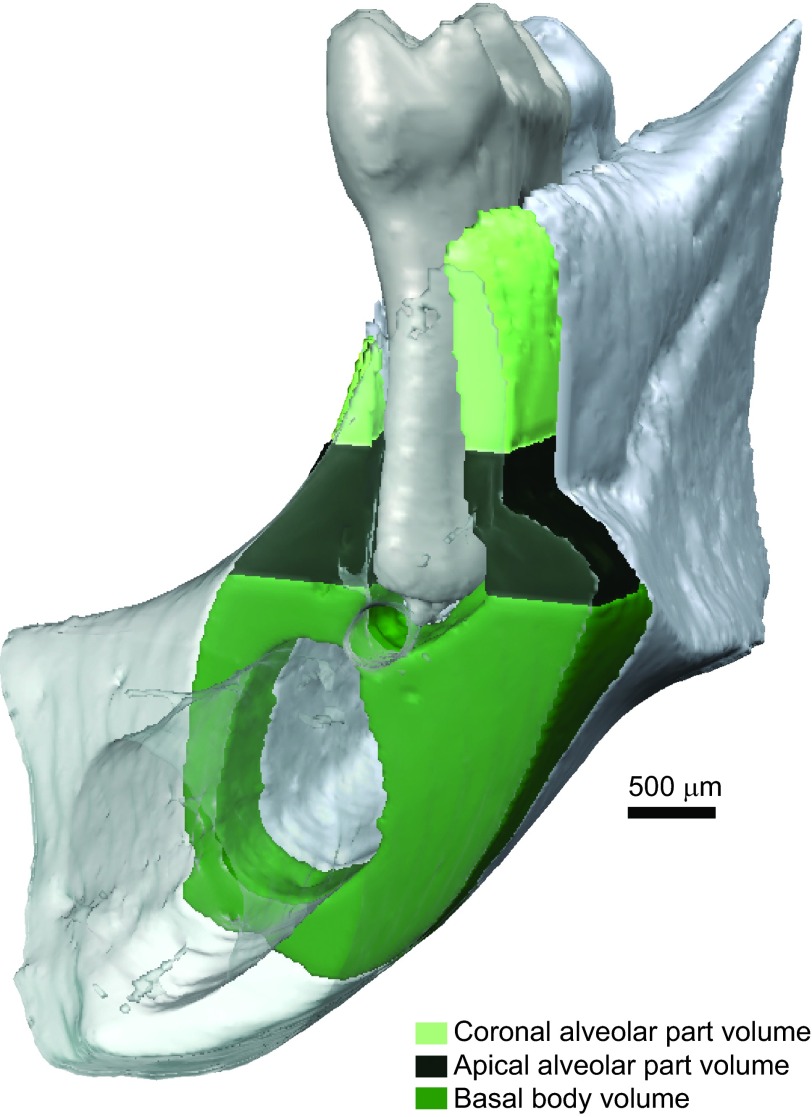

Figure 1.

Regions of interest in the 3D analysis of µCT images of bone parts. 3D regions are defined and automatically segmented in the Definiens Developer XD 2.0.0. 3D, three-dimensional; µCT, micro-computed tomography.

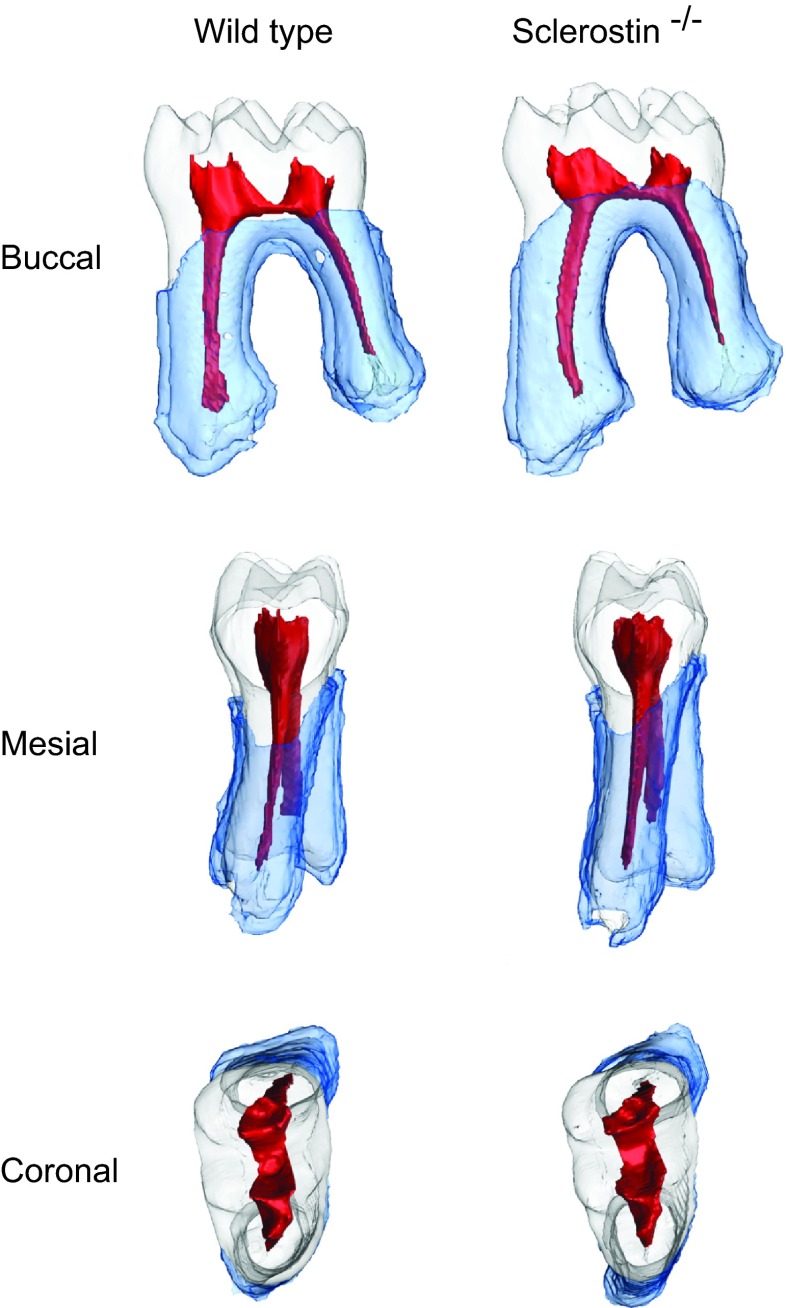

Figure 2.

Segmentation of different tissue types in the first molar as used for measurements in Definiens Developer XD 2.0.0. Tooth-tissue (cementum, dentin, enamelum) and pulp chamber were manually segmented using the Amira software, and the periodontal ligament space was automatically segmented in the Definiens Developer XD 2.0.0. No obvious changes in tooth morphology or the dimension of the dental pulp are visible, which is also supported by the statistical analysis.

Histology and histomorphometric analysis

Skulls were fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde and stored in 70% alcohol. Mandibles were dehydrated in alcohol and embedded in light-cured resin (Technovit 7200 VLC + BPO; Heraeus Kulzer & Co., Wehrheim, Germany). Mandibles were further processed with Exakt Cutting and Grinding equipment (Exact Apparatebau, Norderstedt, Germany). Thin-ground sections of the first molar of three Sost KO and four wild-type mice were prepared along the mesial tooth root canal in the buccolingual direction using the cutting-grinding technique described by Donath24 and stained according to Levai Laczko. Thin ground sections of three sclerostin knockouts and four wild-type controls were subjected to histomorphometric analysis. Digital pictures were obtained with the Olympus dotSlide 2.4 digital virtual microscopy system (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a resolution of 321.5 nm per pixel.

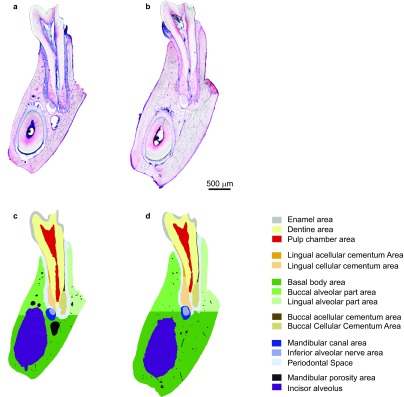

The regions of interest were manually classified with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) using false colour staining. Measurements were performed on enamel, dentin, pulp chamber, mandibular canal, inferior alveolar nerve, basal body area and mandibular porosity. Additionally, the cementum and the alveolar part were split into anatomical sides (lingual/buccal) and then measured, as shown in Figure 3. The cementum was measured in two apical and two coronal regions. The coronal region extended 200 µm in the apical direction from the most coronal point of the cement on each side. The apical region was measured from the most apical point of the cement on each side that extended 200 µm in coronal direction, starting at the most apical point of the tooth root canal (or the dentin on the samples where the pulp did not intersect in this area). Width measurements were performed by averaging the horizontal extent of each row of pixels in the corresponding region. The thickness of a region was measured by dividing its area by its length. The measurement was performed automatically using a Definiens rule set (Definiens Developer XD Version 2.0.0; Definiens, Munich, Germany) created for this purpose. Regions of interest are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Regions of interest in the 2D analysis of histological thin ground sections. (a, c) Wild-type, (b, d) sclerostin knockout mice; (a, b) Levai–Laczko staining, (c, d) segmentation of different tissue types as used for measurements in Definiens Developer XD 2.0.0 and classified in false colour. Thin ground sections of first molars were prepared along the canal of the mesial tooth root in the buccolingual direction. 2D, two-dimensional.

Statistics

Student's t-test was performed for three-dimensional (3D) data (volume, thickness), correcting for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. P values below 0.05 were considered significant. Descriptive statistical methods (mean±standard deviation) were applied to the two-dimensional (2D) data (area, width). All computations were performed using the R 2.15.1 program (http://www.R-project.org).

Results

Dental and periodontal phenotypes

Histological analyses showed that the dental and periodontal phenotypes of the 4-month-old wild-type animals were similar to those of the sclerostin knockout mice. The anatomy and dimensions of the first mandibular molars were similar in the wild-type and knockout mice. The enamel had a comparable structure and thickness, and enamel-free areas were detected in both the wild-type and knockout mice. The dentin consisted of mineralized dentin matrix, dentinal tubules and predentin lined by odontoblasts. The dentin thickness was similar in both groups, and no overt differences were observed regarding the dimensions of the pulp chamber.

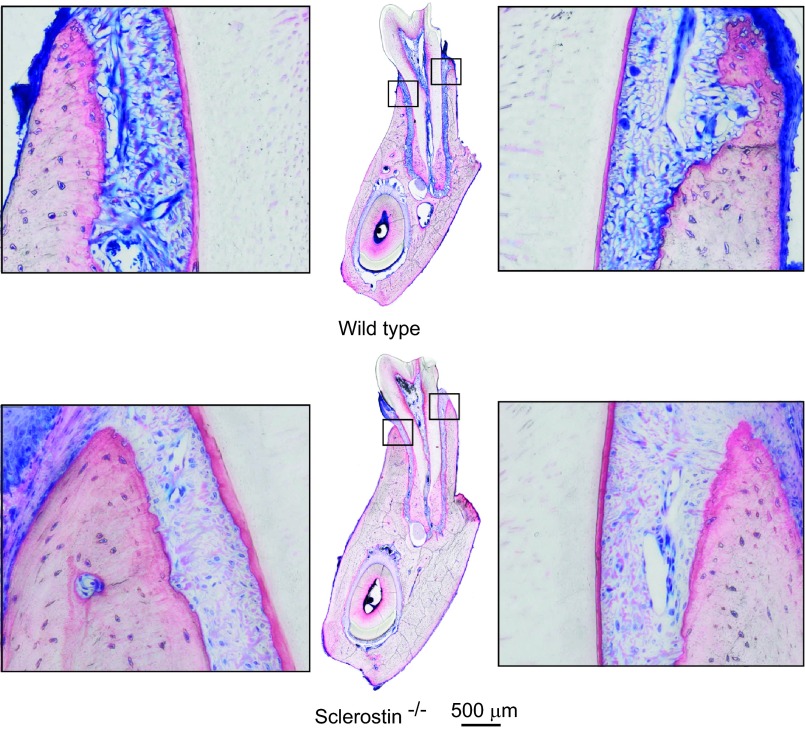

As in the wild-type animals, the periodontium (consisting of gingiva, dental cementum, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone) showed healthy conditions in the sclerostin knockout mice. In both groups, acellular cementum was present in the coronal half of the roots, whereas cellular cementum prevailed in the apical root portion. In the wild-type and sclerostin knockout mice, the acellular cementum was free of cementocytes, whereas the cellular cementum contained many lacunae filled with cementocytes. Sites with thicker acellular and cellular cementum were observed in the sclerostin knockout mice. No apparent difference was observed concerning the periodontal ligament structure (i.e., blood vessels, fibroblasts and collagen fibres that were inserted into the cementum and bone). However, in animals with the sclerostin deletion, the periodontal ligament width was slightly reduced.

The most striking difference was observed in the basal portion of the mandibular bone. This bone was thicker in sclerostin knockout mice than in wild-type animals. Similarly, the lingual and buccal alveolar part showed regions with increased bone thickness in sclerostin knockout mice. Structurally, however, the jaw bone and alveolar bone did not reveal any overt differences between the wild-type and knockout mice, e.g., the bone presented with cement lines and many osteocytes.

Jaw bone in sclerostin knockout mice

The basal mandibular bone in the sclerostin knockout mice was approximately twice the size of that of the wild-type animals (volume +168.9% and thickness +105.6%) (Table 1). The coronal and, to a lesser extent, the apical part of alveolar part were increased following sclerostin deletion (coronal volume +51.2% and thickness +58.4% apical volume +26.8% and thickness +27.1%). Histomorphometric data support the µCT data (Figure 4 and Table 2). The histomorphometric analysis further suggests that the sclerostin deletion reduced the mandibular porosity (−78.4%). The nerve canal area and the inferior alveolar nerve area were increased (+11.2% and +46.2%, respectively). Together, these results indicate that the sclerostin deletion is responsible for the observed bone increase, and interestingly, this deletion plays a larger role in the basal body than in the alveolar part.

Table 1. Micro-computed tomography data of two groups with six animals each.

| Parameters | Number | Mean | Variety of wild type/% | Standard deviation | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild tpye | Sclerostin | Wild tpye | Sclerostin | Wild tpye | Sclerostin | |||

| Basal body volume | 6 | 6 | 2.14×108 | 5.75×108 | +168.89 | 2.37×107 | 4.38×107 | <0.001 |

| Basal body thickness | 6 | 6 | 455.03 | 935.44 | +105.58 | 41.24 | 112.22 | <0.001 |

| Coronal alveolar part volume | 6 | 6 | 5.32×107 | 8.04×107 | +51.20 | 8.60×106 | 1.37×107 | 0.041 |

| Coronal alveolar part thickness | 6 | 6 | 152.85 | 242.15 | +58.43 | 26.24 | 20.91 | 0.002 |

| Apical alveolar part volume | 6 | 6 | 1.19×108 | 1.51×108 | +26.79 | 8.41×106 | 1.41×107 | 0.017 |

| Apical alveolar part thickness | 6 | 6 | 590.39 | 750.57 | +27.13 | 42.03 | 72.00 | 0.018 |

| Tooth volume | 6 | 6 | 1.12×109 | 1.14×109 | +1.15 | 3.36×107 | 6.89×107 | 1 |

| Pulp chamber volume | 6 | 6 | 8.62×107 | 7.68×107 | −10.89 | 6.63×106 | 1.29×107 | 0.72 |

Groups were compared by two-way analysis of variance on in-transformed data with post hoc multiple t-tests, according to the Benjamin–Hochberg procedure. Values are given in μm.

Figure 4.

Close-up of buccal and lingual acellular cement of the wild-type and sclerostin knockout mouse models. The magnification shows the area immediately below the alveolar crest. The cementum appears reddish in the Levai–Laczko staining. Overall, the deletion of sclerostin led to a phenotype characterised by a thickened acellular cementum, as reported in Table 2. The arrowhead indicates the position of the apex of the alveolar crest.

Table 2. Histomorphometric data representing four wild type and three SOST knockout animals.

| Parameters | Number | Mean | Variety of wild type/% | Standard deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Sclerostin | Wild type | Sclerostin | Wild tpye | Sclerostin | ||

| Basal body area | 4 | 3 | 7.73×105 | 1.87×106 | +141.72 | 43 636 | 1.04×105 |

| Basal body width | 4 | 3 | 500.84 | 940.42 | +87.77 | 26.20 | 47.45 |

| Alveolar part area | 4 | 3 | 5.75×105 | 8.21×105 | +42.86 | 44 778 | 24 692 |

| Alveolar part width | 4 | 3 | 411.43 | 550.66 | +33.84 | 17.80 | 20.25 |

| Periodontal space area | 4 | 3 | 2.84×105 | 2.28×105 | −19.71 | 19 336 | 16 661 |

| Periodontal space width | 4 | 3 | 80.317 | 61.143 | −23.87 | 7.34 | 3.57 |

| Dentine area | 4 | 3 | 6.27×105 | 6.45×105 | +2.86 | 53 242 | 49 833 |

| Total cement area | 4 | 3 | 99 884 | 1.51×105 | +50.68 | 16 162 | 28 224 |

| Total cement width | 4 | 3 | 258.77 | 327.94 | +26.73 | 30.92 | 40.53 |

| Buccal acellular cement area | 4 | 3 | 52 111 | 72 729 | +39.57 | 10 735 | 22 294 |

| Buccal acellular cement width | 4 | 3 | 128.14 | 153.59 | +19.86 | 16.27 | 27.70 |

| Buccal cellular cement area | 4 | 3 | 1 568 | 2 070 | +32.01 | 176.14 | 202.46 |

| Buccal cellular cement width | 4 | 3 | 5.09 | 6.85 | +34.65 | 0.63 | 0.29 |

| Lingual acellular cement area | 4 | 3 | 42 949 | 70 715 | +64.65 | 11 781 | 16 061 |

| Lingual acellular cement width | 4 | 3 | 117.51 | 154.59 | +31.55 | 23.09 | 14.01 |

| Lingual cellular cement area | 4 | 3 | 3 256.42 | 4 988.80 | +53.23 | 638.81 | 160.06 |

| Lingual cellular cement width | 4 | 3 | 8.03 | 12.90 | +60.71 | 1.82 | 1.47 |

| Mandibular porosity area | 4 | 3 | 1.02×105 | 21 991 | −78.42 | 26 601 | 2 643.9 |

| Mandibular canal area | 4 | 3 | 55 155 | 61 327 | +11.19 | 2 327.1 | 4 496.7 |

| Inferior alveolar nerve area | 4 | 3 | 17 454 | 25 512 | +46.17 | 1 722.4 | 2 578.7 |

| Pulp chamber area | 4 | 3 | 2.03×105 | 1.32×105 | −35.06 | 15 078 | 35 230 |

A descriptive statistic was performed. Values are given in μm.

First molar and the periodontal ligament space in sclerostin knockout mice

Tooth dimensions, e.g., tooth volume (+1.2%) and pulp chamber (−10.9%), were not significantly changed in the sclerostin knockout animals (Figure 2 and Table 1). The histomorphometric data basically supported the µCT findings (Table 2). Moreover, the histomorphometric data further showed a tendency towards a smaller periodontal ligament space (area −19.7% and width −23.9%) following sclerostin deletion. These findings suggest that the development of the outer dimensions of the tooth occur independently of the sclerostin gene, while there is a trend towards a smaller pulp chamber and periodontal ligament space.

Cementum in sclerostin knockout mice

Based on the histomorphometric analysis, the sclerostin knockout caused an increase in lingual acellular cementum (area +53.2% and width +60.7%) and cellular cementum (area +64.6% and width +31.5%). The increase was visible to a lesser extent in the buccal acellular cementum (area +39.57% and width +19.86%) and cellular cementum (area +32.0% and width +34.7%). Thus, the deletion of sclerostin led to a phenotype characterized by thickened acellular and cellular cementum. The data are summarized in Table 2 and a representative picture is shown in Figure 4. Cementum was not evaluated separately in the μCT imaging. Cementum, dentin and enamel were undistinguishable in the μCT images and thus, were classified as one tissue, labelled ‘tooth'.

Discussion

The studies described here reveal that (i) sclerostin controls the dimensions of the mandible, through the basal bone and the tooth-supporting alveolar part; (ii) sclerostin controls the dimensions of the cementum and the periodontal space; and (iii) sclerostin affects the dimensions of the pulp chamber, while the outer dimension of the first molar was not affected. The effect of the sclerostin on the mandibular bone and cementum presumably resulted from the ability of sclerostin to antagonize Wnt signalling. Thus, once the antagonist cannot be expressed properly, the unlocked Wnt pathway stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts and likely also cementocytes and odontoblasts.

In accordance with the sclerostin deletion results, the stabilisation of β-catenin leads to the premature differentiation of odontoblasts and differentiation of cementoblasts and causes marked dentin and cementum formation.22 Because the lack of sclerostin also should increase Wnt/β-catenin signalling, an overlapping phenotype would be expected. However, β-catenin is not the exclusive Wnt signalling pathway. At least in bone, β-catenin mutants do not fully mimic the phenotype of receptor and antagonist mutants, although their overall bone mass phenotype is consistent.25,26 Thus, our description of the dental phenotype of sclerostin knockout mice complements the existing data on Wnt/β-catenin in the mineralized tissue related to dentistry.

It is clear from this study that the basal mandibular bone in sclerostin knockout mice was approximately doubled in size compared to that of the wild-type animals, while the coronal and particularly the apical part of the alveolar bone showed a lesser increase. These data basically support previous observations that the sclerostin knockout caused a more pronounced increase of trabecular structure of the distal femoral metaphysis, compared to cortical bone of the femur midshaft.11,26 However, as we have solely focused on cortical structures, the anatomical gradient was unexpected. The anabolic effect caused by the blocking of sclerostin most likely depends on the remaining biomechanical control of the respective anatomical structures.27,28 Thus, the bones in the skull are heterogeneous, and it would be worthwhile to further investigate these site-specific changes to determine which types of bone are sensitive to a lack of sclerostin signalling.

Acellular cementum is a unique tissue, while cellular cementum and bone share some similarities.29,30 Thus, the obvious increase in acellular cementum deserves attention. Acellular cementum is formed during tooth development, not as a consequence of postnatal modelling or remodelling. In accordance with our findings, excessive acellular cementum formation was observed after constitutive β-catenin stabilisation.22 This supports the role of Wnt/β-catenin signalling in the formation of the dentoalveolar complex.31 Whether sclerostin is functionally linked with the control of acellular cementum in phosphate metabolism32,33 and mutations of the progressive ankylosis protein and plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 genes34,35 remains unclear. However, mouse models provide valuable insights into the biology of the mysterious process of cementogenesis.

Accordingly, mouse models have become increasingly important in dentistry. Recent studies have reported on the phenotypic changes that occur upon the selective deletion of BMP4 in osteoblasts and odontoblasts.36 Transgenic mice are another useful model system and were used to show that ameloblastin overexpression induces alveolar bone loss and tooth root resorption.37 Recently, signalling cascades connecting dentin matrix protein 1 and dentin sialophosphoprotein were studied in rodent models.35 Similar models with sclerostin might confirm the recent findings, as Wnt/β-catenin signalling is complex.2 Moreover, mouse models revealing the role of DKK-1, another antagonist of Wnt/β-catenin signalling, on the tooth, the dimension of the tooth and the periodontium would be worth investigating, particularly because DKK1 is a negative regulator of normal bone homeostasis in vivo.38 Taken together, these mouse models show phenotypes and pathophysiological mechanisms that are of clinical relevance.

The clinical relevance of the present study is twofold. First, this study helps us to understand the pathological mechanisms that occur in tooth development in van Buchem disease or sclerosteosis patients. In accordance with the clinical picture, there is an overgrowth of not only the mandible, but also the alveolar bone, which explains the difficulty of tooth extractions in patients lacking sclerostin.8 Our findings also supplement the radiological observations of the cementum thickness in van Buchem disease patients.8 Based on our findings, it appears to be worthwhile to perform further analysis of cementum in the extracted teeth of patients with van Buchem disease or sclerosteosis. Moreover, it is worthwhile to test the potential of sclerostin-inhibiting pharmacological therapies for the promotion of periodontal regeneration, including new cementum formation after periodontal treatment and tooth movement.16

The present study has several limitations. First, it focused on the examination of the mandible, and the maxillae were not examined. This decision was based on the less complicated preparation of the histological specimens from the first molar in the mouse mandible. The preclinical data are presumably also representative for the maxilla, as patients with sclerosteosis and van Buchem disease are both severely affected.4,5,6,7 Another limitation is that in the present study, the phenotype was investigated at one time point, which does not allow any conclusions on the effect of sclerostin during tooth development. This time point was chosen because tooth development ceases by 4 months of age in mice.

The results presented here thus suggest that the lack of sclerostin causes more basal and alveolar bone deposition and supports the formation of cementum. It will now be important to investigate the therapeutic relevance of targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway in three contexts: periodontal regeneration, implant dentistry and dentin formation.

Acknowledgments

Novartis Institutes provided the skulls for BioMedical Research, Musculoskeletal Disease Area, Basel, Switzerland. The Department of Oral Surgery, Head Professor G Watzek, Bernhard Gottlieb Dental School, and the Medical University of Vienna financially supported the analysis. The authors are holding positions and are paid by the affiliated institutions (Department of Oral Surgery and Stomatology, Head Professor D Buser; Ludwig Bolzmann Institute of Experimental Traumatology, Head Professor H Redl). We thank G Zanoni for the μCT analysis, S Lettner for the statistical support and S Tangl and S Toka for the technical support. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Li X, Zhang Y, Kang H, et al. Sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 and antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280 20:19883–19887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19 2:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bezooijen RL, Roelen BA, Visser A, et al. Sclerostin is an osteocyte-expressed negative regulator of bone formation, but not a classical BMP antagonist. J Exp Med. 2004;199 6:805–814. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkow ME, Gardner JC, van Ness J, et al. Bone dysplasia sclerosteosis results from loss of the SOST gene product, a novel cystine knot-containing protein. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68 3:577–589. doi: 10.1086/318811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemans W, Patel N, Ebeling M, et al. Identification of a 52 kb deletion downstream of the SOST gene in patients with van Buchem disease. J Med Genet. 2002;39 2:91–97. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JC, van Bezooijen RL, Mervis B, et al. Bone mineral density in sclerosteosis; affected individuals and gene carriers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90 12:6392–6395. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen LX, Hamersma H, Gardner J, et al. Dental and oral manifestations of sclerosteosis. Int Dent J. 2001;51 4:287–290. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bezooijen RL, Bronckers AL, Gortzak RA, et al. Sclerostin in mineralized matrices and van Buchem disease. J Dent Res. 2009;88 6:569–574. doi: 10.1177/0022034509338340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager A, Gotz W, Lossdorfer S, et al. Localization of SOST/sclerostin in cementocytes in vivo and in mineralizing periodontal ligament cells in vitro. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45 2:246–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnen SD, Gotz W, Baxmann M, et al. Immunohistochemical evidence for sclerostin during cementogenesis in mice. Ann Anat. 2012;194 5:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ominsky MS, Niu QT, et al. Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23 6:860–869. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer I, Loots GG, Studer A, et al. Parathyroid hormone (PTH)-induced bone gain is blunted in SOST overexpressing and deficient mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25 2:178–189. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ominsky MS, Tan HL, et al. Increased callus mass and enhanced strength during fracture healing in mice lacking the sclerostin gene. Bone. 2011;49 6:1178–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewiecki EM. New targets for intervention in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7 11:631–638. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ominsky MS, Warmington KS, et al. Sclerostin antibody treatment increases bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24 4:578–588. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhi D, Jang G, Stouch B, et al. Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26 1:19–26. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald MM, Morse A, Mikulec K, et al. Inhibition of sclerostin by systemic treatment with sclerostin antibody enhances healing of proximal tibial defects in ovariectomized rats. J Orthop Res. 2012;30 10:1541–1548. doi: 10.1002/jor.22109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virdi AS, Liu M, Sena K, et al. Sclerostin antibody increases bone volume and enhances implant fixation in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94 18:1670–1680. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taut AD, Jin Q, Chung JH, et al. Sclerostin antibody stimulates bone regeneration following experimental periodontitis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28 11:2347–2356. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka T, Yokose S. Spatiotemporal expression of sclerostin in odontoblasts during embryonic mouse tooth morphogenesis. J Endod. 2011;37 3:340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjeld K, Kettunen P, Furmanek T, et al. Dynamic expression of Wnt signaling-related Dickkopf1, -2, and -3 mRNAs in the developing mouse tooth. Dev Dyn. 2005;233 1:161–166. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Lee JY, Baek JA, et al. Constitutive stabilization of ss-catenin in the dental mesenchyme leads to excessive dentin and cementum formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412 4:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Bae CH, Lee JC, et al. Beta-catenin is required in odontoblasts for tooth root formation. J Dent Res. 2013;92 3:215–221. doi: 10.1177/0022034512470137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath K.Die Trenn-Dünnschliff-Technik zur Herstellung histologischer Präparate von nicht schneidbaren Geweben und Materialien Der Präparator 1988345197–206.Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Kolpakova E, Olsen BR. Wnt/beta-catenin—a canonical tale of cell-fate choice in the vertebrate skeleton. Dev Cell. 2005;8 5:626–627. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niziolek PJ, Farmer TL, Cui Y, et al. High-bone-mass-producing mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway result in distinct skeletal phenotypes. Bone. 2011;49 5:1010–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias BR, Aspenberg P, Agholme F. Paradoxical Sost gene expression response to mechanical unloading in metaphyseal bone. Bone. 2013;53 2:515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu X, Rhee Y, Condon KW, et al. Sost downregulation and local Wnt signaling are required for the osteogenic response to mechanical loading. Bone. 2012;50 1:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosshardt DD. Are cementoblasts a subpopulation of osteoblasts or a unique phenotype. J Dent Res. 2005;84 5:390–406. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster BL, Popowics TE, Fong HK, et al. Advances in defining regulators of cementum development and periodontal regeneration. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;78:47–126. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)78003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Bae CH, Jang EH, et al. Col1a1-cre mediated activation of beta-catenin leads to aberrant dento-alveolar complex formation. Anat Cell Biol. 2012;45 3:193–202. doi: 10.5115/acb.2012.45.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster BL, Nagatomo KJ, Nociti FH, Jr, et al. Central role of pyrophosphate in acellular cementum formation. PLoS One. 2012;7 6:e38393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beertsen W, VandenBos T, Everts V. Root development in mice lacking functional tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase gene: inhibition of acellular cementum formation. J Dent Res. 1999;78 6:1221–1229. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nociti FH, Jr, Berry JE, Foster BL, et al. Cementum: a phosphate-sensitive tissue. J Dent Res. 2002;81 12:817–821. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues TL, Nagatomo KJ, Foster BL, et al. Modulation of phosphate/pyrophosphate metabolism to regenerate the periodontium: a novel in vivo approach. J Periodontol. 2011;82 12:1757–1766. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluhak-Heinrich J, Guo D, Yang W, et al. New roles and mechanism of action of BMP4 in postnatal tooth cytodifferentiation. Bone. 2010;46 6:1533–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Ito Y, Atsawasuwan P, et al. Ameloblastin modulates osteoclastogenesis through the integrin/ERK pathway. Bone. 2013;54 1:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BT, Joiner DM, Oyserman SM, et al. Bone mass is inversely proportional to Dkk1 levels in mice. Bone. 2007;41 3:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]