Abstract

The following report from the field focuses on the authors’ collective efforts to operate an ad hoc safer injection facility (SIF) out of portapotties (portable toilets) in an area of the South Bronx that has consistently experienced some of the highest overdose morbidity and mortality rates in New York City over the past decade (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2011, 2015, 2016). Safer injection facilities (also known as supervised injection facilities, drug consumption rooms, etc.) operating outside the US provide a legal, hygienic, and supervised environment for individuals to use drugs in order to minimize the likelihood of fatal overdose and the spread of blood-borne infections while reducing public injection. In the US, the operation of SIFs is federally prohibited by the federal “Crack House” statute though federal, state, and local elected officials can sanction their operation to various degrees (Beletsky, Davis, Anderson, & Burris, 2008).

The activists, researchers, undergraduate students and peers from syringe exchange programs who came together to operate the portapotties discovered that they were, in many ways, emblematic of neoliberal solutions to disease prevention: primarily focused on auditing individual risk behaviors and virtually blind to the wider social context that shapes those lives. That social context — the culture of drug injection — was and is out in the open for all of us to see. Going forward, the cultural anthropologist’s toolbox will be opened up and used by large groups of undergraduate students to better understand the culture of drug use and how it is changing.

THE PORTAPOTTY EXPERIMENT

Who knew that there were so many types of portapotties? When we visited the website for “Call-A-Head,” to rent a couple of units for the weekend, we didn’t expect to find 17 different models. Since prices for short-term rentals were not listed and it was difficult to choose based on the photos and specs, we called the 1–800 number to get more information. The sales woman on the phone asked several questions about our “event,” including where it was going to be held and how many people we expected to use the portapotties over the two days. She didn’t flinch when we told her the zip code: one of the most notoriously violent neighborhoods in the South Bronx. And she didn’t complain when we told her that we wanted the portapotties placed on a parcel of land that was posted with signs that said “No Trespassing – NYPD Property.” We decided that it was probably best that we not tell her that we didn’t expect many people to use them as bathrooms, but rather, to use them as private drug injection facilities; instead, we told her that we figured about 75 people per day would use them at the event. “Ok, no problem,” she said, and she immediately recommended what must have been one of their priciest units; two units would cost us $530 plus tax and a 50-dollar delivery and pick-up fee. Thinking about what we intended to do with the portapotties, the ad was almost too funny: “THE CEREMONY TOILET - Luxury Portable Restroom Rental for Weddings and Upscale Special Events.” The website went on to rave about what we would get for our money:

This porta potty rental has all the accessories of an indoor public restroom, yet it is completely mobile and self-contained, requiring no outside water source. The CEREMONY TOILET has a full service bathroom that will have special event guests forgetting that they are using an outdoor porta potty. An inclusive hand washing sink has a foot operated pump for hands free washing.

The porta potty’s flush toilet also works on a foot operated pump for hands free flushing, providing the greatest sanitary protection. The CEREMONY TOILET has premium accessories that are delivered standard with its rental. This elegant portable restroom rental includes our Headmist time released air freshener, Headliner dispenser filled with our toilet seat covers, soap dispenser filled with our antibacterial soap, filled paper towel dispenser and a beautiful floral arrangement. These high end accessories will provide your special event guests with VIP treatment in temporary portable toilets.

The spacious interior of the porta potty has a lockable door and occupancy sign for security that special event guests will have complete privacy when using this portable restroom. Also included inside this VIP portable toilet is an interior mirror, dual roll covered toilet paper dispenser, two convenience shelves and a coat and hat hook. Its translucent roof provides natural light for day and an interior solar powered light for evening use of the portable restroom. A built in ventilation system with 6 vents will circulate the air to eliminate any odor causing issues within this premium porta potty.

“The Ceremony” sounded perfect for our needs and we could hardly contain our amusement; the only thing missing was a bathroom attendant in a tuxedo standing in front of the units and offering drug users their choice of different gauge needles before they went in to inject. We considered renting a tuxedo ourselves, but thought that if we were to get arrested over the weekend – and that was a distinct possibility given what we were doing and where – then it might not be good to be in Bronx central booking with a rental tux on, though it might be a good look when appearing before a judge later. In any event, we decided against the tux.

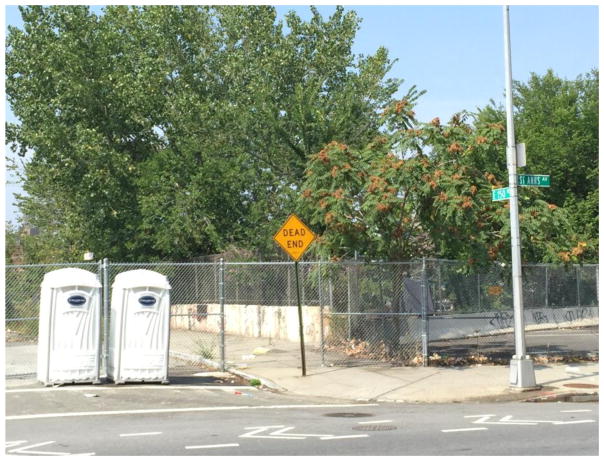

Portapotties outside the future home of the 40th Precinct and approximately 100ft from the entrance to The Hole.

The idea for renting portapotties to use as SIFs for drug injectors in the South Bronx came out of discussions that the various members of our group had over the previous weeks about three related issues that had occupied our thinking and work over the last few years, including:

The findings from our study and others about drug-related overdoses that occur in public bathrooms, especially those in fast food restaurants that are frequently utilized, and where the amenities, anonymity, and privacy have proven attractive to injectors (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2010, 2013; Wolfson-Stofko, Bennett, Elliott, & Curtis, 2017). The problem is particularly acute in parts of the South Bronx, but when managers of these establishments were asked if they would consent to having Sharps Containers installed in their bathrooms to dispose of used syringes, the answer was always emphatically ‘no’ (Wolfson-Stofko, et. al., unpublished). Some managers were interested in getting trained in overdose prevention and response, but their supervisors forbade it (Wolfson-Stofko, et. al., unpublished). We discussed the idea of installing Sharps Containers in public places that were adjacent to fast food restaurants, and even placing portapotties there to encourage injectors to use them rather than the fast food bathrooms, but we decided that neither of those options was realistic.

The growing number of drug injectors that were spending time at “The Hole,” an abandoned and mostly underground rail line that bisects the South Bronx and is partially exposed for a few blocks beginning at 150th Street and St. Ann’s Avenue. This site has long had a reputation in the South Bronx as a nexus of drugs and crime, and in the Fall of 2015, it was selected as one of 7 sites around the city for our study of “homeless hot spots” that was funded by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice (Curtis et al., 2016). But before our research team had a chance to begin collecting data at that site, the Mayor and Police Commissioner visited that location with a fleet of garbage trucks and bulldozers to trumpet a clean-up of the area in advance of Pope Francis’s visit later that fall. In an attempt to show compassion, the city reserved a measly ten beds in a local shelter for the hundred or so homeless individuals residing in The Hole (Woodruff, 2016). After evicting the large number of homeless injectors who had been living on or near the tracks, the city erected a chain-link fence around the area. The fence lasted through the winter, but sometime in the spring, a car smashed through it and people started trickling back in; and by early summer 2016, The Hole had again become a source of concern among staff at the Bronx harm reduction programs who started to resupply injectors who visited there on a regular basis.

The frustration that many of us felt about the continued lack of a SIF in NYC (Singal, 2016; Wolfson-Stofko, 2014). Many members of the harm reduction community – including allies at the NY State AIDS Institute – have spent years advocating for the establishment of SIFs in the city. In 2009, for example, a conference whose explicit purpose was to prepare the local landscape for the establishment of an SIF in the city was held at John Jay College. Over the last few years, an coalition of activists known as SIF NYC has made substantial progress in several areas that are important to the future of local SIFs, but recently, when asked when we are likely to see the first, pilot SIFs in the city, one member of the group said, “3–5 years” (personal communication, 2016). To us, that was just too long to wait.

So, the idea to rent portapotties to use as SIFs came about as the result of a confluence of these problems and the interest that a group of us had in doing something about them. Our group consisted of activists, researchers, students, and SEP staff and peer outreach workers who understood the fierce urgency of now. Our plan was to operate the portapotties as SIFs on 150th St. and St. Ann’s Avenue in the South Bronx, sunup-to-sundown, over a weekend in early September, but once we paid for the units, a customer service representative at Call-A-Head told us they would be delivered on Thursday and picked up the following Monday. “Are they going to be locked when you leave them on the street,” we asked? “No,” she said, “but we can put zip ties on the doors, if you like.” Wild thoughts about the kinds of damages that might happen to unsecured portapotties in the South Bronx on Thursday and Friday nights sent us scrambling to buy padlocks to replace the zip ties, and we dashed to the Bronx when we received the call that the units were there to switch them over.

When we arrived to see our two units on the recessed sidewalk, they were the nicest portapotties that we had ever seen: brand new, with no hint of the smell that is typically associated with them, and all the amenities that were promised on the website, even a plastic potted plant. We set about evaluating the inside for our purposes. One problematic feature that we had not appreciated while viewing the units on the website was the sink: the prospect of unpotable water coming out of the faucet and being used for drug preparation, or the possibility of someone accidentally activating the sink and washing away their drugs, was cause for concern. Ric spent a few minutes fashioning a cardboard shield which he taped to the foot-pump mechanism that activated the sink’s faucet, and once it was in place, we were satisfied that it would prevent this kind of catastrophe.

After making sure that the units were locked, we spent the next day, Friday, formulating our plans for the weekend. We agreed that people would be allotted use of the portapotties for uninterrupted 15-minute intervals so as not to rush drug preparation or injection. All volunteers, including the undergraduate students, would have to be trained in how to use naloxone to reverse an overdose and provided with naloxone kits. We also discussed contingency plans in case we had problems once the portapotties were opened for business, so to speak. One of the biggest questions we asked ourselves was, “What will we do if someone overdoses in one of the portapotties?” After much discussion about using naloxone, rescue breathing, using oxygen to revive those that were not badly overdosed and other procedures, we finally decided that we would simply administer the necessary amount of naloxone to get the person breathing then call 911 and stay with the person until EMS - and hopefully not the police - arrived. Above all, we resolved to treat people – who, as drug users, would be conducting one of the most stigmatizing acts in modern society - with dignity and respect.

There was also much debate about whether to allow participants to actually use the portapotties as a bathroom since their main purpose was to provide a sanitary, safer, and semi-private space for injection. The group ultimately decided that we would designate one unit for injection-only and the other as a multi-purpose portapotty, the “hitter” and the “shitter.” We also discussed crowd control: how to ensure that there was not a long line in front of the door that might lead to fights and draw the unwanted attention of the police or neighborhood residents. We decided that if a line began to form, we would have people wait in a nearby park and would notify them when it was their turn, in a similar way as a deli counter operates (“Now serving number 18!”). What if the police showed up and wanted to arrest us and whoever they found in the bathrooms? We decided that the risk of arrest was real, but that we would try to reduce our exposure by calling on some of our friends in the NYPD to seek their advice, and Brett called the Bronx Defenders (bronxdefenders.org) to let them know what we were doing and encouraged everyone to write their Legal Emergency Hotline on their forearm in indelible ink, just in case we took a ride in the paddy wagon and needed a lawyer’s number.

Arriving shortly after 7am on Saturday, we opened up the portapotties for business. The first thing we did was remove the internal plastic lock from the door so that no one would get trapped in the portapotty if they overdosed and that we had access in case we needed to intervene. We figured that people would probably sit and try and prepare their drugs on their lap so Brett went and purchased plastic dinner trays and wrapped them with multiple layers of aluminum foil which could be replaced after each use. We also placed a small Sharps Container inside and Ric bought some bleach wipes and so people could wipe down the inside of the portapotty after they were done.

The street was mostly deserted, but there was already a steady trickle of people going into and coming out of The Hole. They didn’t seem to pay any mind to the three of us who had arrived and were setting up for the day or ask any questions about the portapotties which, by then, had already been sitting there for about 36 hours. Calling out to them in Spanish to ask if they needed any fresh syringes and other equipment, they came to our car and took a couple of pre-assembled bags of injection supplies from us. When we told them that they could use the portapotties, if they wanted to, and showed them how nice they looked inside, they said that they were on their way to hustle some money, but that they might consider using them when they returned. Perhaps the supplies that we provided led them to associate us with the local syringe exchange programs, but they did not seem particularly concerned that they had not met us before or appear worried that the portapotties might be an elaborate scheme perpetrated by the police. When they returned later, one of the men did use the portapotty, but not to inject.

The portapotties taught us a valuable lesson early that day; that is, what you think is a solution to a problem might not always be seen that way by the people you are trying to help. It is always better to ask first, and that is part of our plan going forward. But, of course, the portapotties were never just for people who inject drugs; after all, putting such luxurious units in the South Bronx was a message for others too. Indeed, the portapotties are a caricature of neoliberal approaches that have come to dominate the work of addressing problems associated with the use of heroin and other drugs: imposed from the top-down, they focused primarily on individuals and their attributes as the metrics of success rather than recognizing that behaviors — especially injection behaviors — are, more often than not, social events with rules, rituals, conventions…dare we say, a culture all its own. It’s no surprise that injectors did not want to abandon the group to inject in comparative luxury by themselves. Anthropologists have been writing about drug cultures for generations (Bourgois, 1995, 2009; Lindesmith, 1947; Weppner, 1977), but the insights gained through this ethnographic fieldwork have not been translated into policy or practice. Perhaps it is too hard for a system that prefers formulaic approaches to problems that can be broken down into simple tasks with outputs that can be counted, but recognizing the influence of factors larger than the individual is critical to achieving better overall outcomes.

We were there for a few hours before the police arrived. Actually, one member of our team was a member of the NYPD and he stopped by for several hours to give us a hand late in the morning. Having served in the 40th Precinct for many years, he was intimately familiar with the history of The Hole and the notorious reputation that it had among local cops as a place where it was always possible to find someone to arrest. He also provided us with a short list of additional locations in the South Bronx where we could bring our portapotty services if we wanted to expand our territory. He called one of his colleagues who was on-duty at the time, and within minutes, a burly cop in a marked sedan arrived, parking right next to the portapotties. We explained what we were doing and showed him the two units. Smiling, he was eager to give us advice about how best to proceed too, but he added that he was worried about the fact that the “brass” continued to believe that they had cleaned up this spot. So, if we called attention to what we were doing — by inviting the media, for example — then he and other rank-and-file cops would likely feel some heat from the “higher-ups.” We reassured him that media attention was not in our plans, and we thanked him for his advice, but after spending about 45 minutes with us, we had to tell him that his presence was probably “bad for business.” “Alright, I gotta go anyway,” he said, “but if you have any problems here, call my boy and he’ll call me, and I’ll be right here to help you out.” It was reassuring to know that the rank-and-file police had our backs, but some of our undergraduates were a bit crestfallen when it became clear that we were not going to get arrested. They were hoping for some “action,” but up to this point, the day had been anticlimactic.

After sitting on the sidewalk for half the day, watching people pass by the portapotties on their way to The Hole, stopping only long enough to get an injection kit from us, we decided that we needed to do something to force the action a bit more: rather than wait for the users to come to us, we’d go to them. Climbing over the concrete barriers in the back of a parking lot on 150th Street and St. Ann’s Avenue in the South Bronx, next to the abandoned lot that is advertised as the future site of the 40th Police precinct, our group of 10 volunteers — including 3 pie-eyed undergrads from John Jay — had to hoist ourselves through the narrow opening in the chain-link fence in order to see where the steady stream of injectors had been going to use drugs. We stepped into a rabbit hole that delivered us into a frightening terrain, teeming with hundreds of thousands of used syringes and other discarded injection equipment. It was essential to walk very slowly and deliberately, especially since there was a steep hill on the other side of the concrete barriers and one slip on the dirt path could send you tumbling onto the abandoned train bed some 30 feet below where a patina of used needles seemed to cover the ground. According to Parkin’s continuum of descending safety which is used to evaluate the different attributes and safety features of injection spaces, this location would be classified as Category C due to its seclusion, poor lighting (particularly at night), and unsanitary nature (Parkin, 2013).

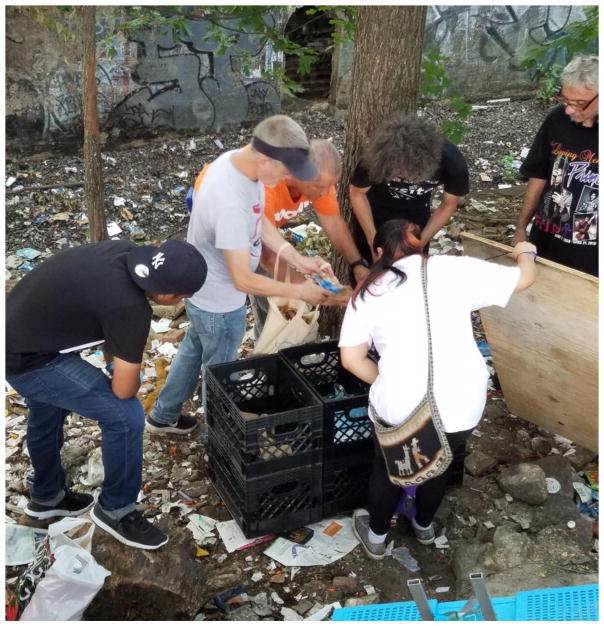

On a tree-sheltered ledge, above the track bed, there were several groups of 3–4 people huddled around bottle caps filled with heroin and other drugs, and they were almost too busy preparing their fixes to take much notice that we were there. To help build rapport and assure them that we meant no harm, we began gathering the used syringes that littered the ground and ultimately collected an entire medium-sized sharps container, but if you looked at the ground, you still couldn’t tell the difference. One injector who spent time there approached Brett and Alex and thanked us for helping clean up the area, assuring us that no one would bother us and that he had our backs. He helped the team clean the area and proudly filled a 1-gallon plastic milk jug with used needles. Recalling some of his experiences at The Hole, he said that the area was busiest at night, but can be dangerous due to the numerous stick-up artists that threaten people with knives and sharpened screwdrivers, though seldom at gunpoint. We didn’t have a reason to disbelieve that story, but he was clearly suffering from paranoia and visual hallucinations; he repeatedly interrupted the conversation to point out law enforcement officers “hiding in the bushes” who he said were trying to catch us, but who none of us ever saw them. Once the rest of the crowd determined that we were not the police, they went back to their business, stopping only long enough to ask if we had a new syringe or two that they might get from us. Once it was clear to us that there was not going to be any drama over our presence there, we set about our business: clearing away needles and other debris when it dawned on us that people had nowhere but the ground to prepare their drugs. Ed and Alexis recalled a stash of unused milk crates in BOOM!Health’s basement and came up with the idea to construct tables that could be used for drug preparation as well as a means for storing supplies. We salvaged the milk crates, drove them over, threw them over the barrier, carried them down the hill and then began zip-tying them to each other. We then placed several thousand sterile syringes, water, alcohol preps, band aids, “cookers and cotton,” tourniquets. On the outside of the crates, we zip-tied overdose kits that contained syringes filled with naloxone so that they were conveniently available to users. We zip-tied “Sharps” containers to the milk crates and to nearby trees so that users could dispose of their used injection equipment, and we put a plywood lid on the boxes so that users would have a better place than the ground to prepare their drugs. Brett then wrote, “Supplies Underneath” and “Don’t Forget Your Narcan” on the plywood to let everyone know about the resources we left for them.

Milk crate tables and supplies being utilized within the first 48 hours.

Besides the three immediate concerns described above that animated our planning around renting the portapotties, to understand how we – a small group of volunteers – came to this location and ended up making these benches is a story that starts in the early 1990s, if not before; it’s a story that lays bare the state’s myopic approach to these intertwined epidemics and our own complicity in allowing it to happen. Indeed, from the very beginning, we were complicit in advocating approaches that were destined to fall short of the desired outcomes, that is, a world that does not feature ugly scars on the urban landscape which attract desperate people and serve as vectors for crime, disorder and disease transmission.

When activists began to deliver “harm reduction” services to the South Bronx and other parts of NYC in the early 1990s, some members of these groups were concerned about the community’s reaction to their efforts, and one of the measures that they took in hopes of winning and maintaining community support was to mark the syringes that they gave out with nail polish so that they could prove that injectors would, in fact, “exchange” their used syringes for sterile ones. At the time, it made sense to take this step because no one was quite sure if drug injectors would comply and return with dirty syringes or whether they would just take the clean ones, not return, and continue sharing syringes in unsafe ways. The “counting” of syringes showed that users would return with used syringes, but the practice proved to be a double-edged sword, one whose legacy – that everything must be counted to the minutest detail – has led to a bureaucracy which regulates existing harm reduction programs in ways that sweat the tiniest details to ensure that taxpayer money is not wasted, but which often misses the bigger picture, like understanding the culture of heroin and injection drug use with its attendant diseases, and consequently, allowing that culture to flare outside the doors of the very centers meant to do something about these problems. Indeed, on any given day, individuals and groups can be observed injecting within a few hundred feet of a syringe exchange because programs are allowed to distribute injection equipment, but forbidden to supervise injections on the premises.

The problem of sweating the details and missing the bigger picture is not unique to harm reduction programs, or even non-profits in general; rather it is a distinguishing feature of neoliberal approaches to governance that has been called “audit culture” (Kamens, 2013; Shore, 2008), that is, a system whose promise to make our lives more rational and orderly conceals disadvantages that are not often discussed: it discourages innovation (except in the service of the audit), avoids larger-picture thinking and planning, and circumscribes social action that takes place outside-the-box. These small-bore, meticulous approaches appear unassailably logical from a public policy perspective and are characterized by “[c]alculative practices including ‘performance indicators’ and ‘benchmarking’ [that] are increasingly being used to measure and reform public sector organizations and improve the productivity and conduct of individuals across a range of professions. These processes have resulted in the development of an increasingly pervasive ‘audit culture’, one that derives its legitimacy from its claims to enhance transparency and accountability” (Shore, 2008).

But despite all the transparency and accountability in spending the public’s money (claims that have repeatedly been shown to be problematic; see, for example, http://www.law360.com/articles/793031/us-takes-on-narco-freedom-drug-rehab-fca-suit), frequent audits of social service providers act to improve the metrics that they select to represent success — the symptoms of the problem — but they do not necessarily solve the larger problem. After more than 25 years of counting syringes and everything else that is provided to drug users, staff that work at harm reduction programs have towed the line on accountability and have become so transparent as to be rendered practically invisible to the public. Many staff feel frustrated about the limited reach that their services provide to drug users; they reminisce about the early days of the movement when their ability to respond to user needs was determined more by interaction with active users rather than with funders, and they aspire to a bigger impact than the state has envisioned for them. The track record of success that harm reduction programs earned in bringing down the rates of HIV infection among drug injectors, for example, stands as testimony of the value of this approach, but at the same time, the impact that the programs have had has primarily been measured by findings which are the compilation of individual-level attributes – like the number of syringes and condoms distributed, the number of referrals to detox, or the number of people who are tested for HIV – rather than community-level indices that represent the wider culture of drug use. On this count, the programs have virtually no systematically-collected data. To funders, understanding and keeping on top of the culture of drug use has never been central to their mission, let alone thinking about how it might be altered; their focus is almost exclusively on altering individual behaviors — especially promoting “drug free” behaviors — but that has meant that the larger social forces that influence drug user’s lives have been afforded little consideration. It’s here that anthropology has a role to play, if there is a way to overcome the audit impulse.

Our actions in the South Bronx were animated by several problems that motivated us, including frustration over the lack of a deep engagement with the culture of drug use that so clearly affected the lives of many drug users, people who were, more often than not, participants in our respective harm reduction programs. Our disengagement with the social and geographic topography of the drug scene has meant that our ability to have any impact on their lives has been primarily limited to what happens in our “bunkers”, our offices in the South Bronx, and to the structured forays that outreach teams make in the area to rack up deliverables for our contracts.

It was in this context that we began to discuss our failure — and everyone else’s — to do anything about one of the most notorious spots in the South Bronx for drug use. The corner of 150th St. and St. Ann’s Avenue: a spot where the remnants of mostly-underground freight train tracks that cut across the South Bronx can be accessed. Despite being marked with signs that say “no trespassing” and “private property,” it has long been a destination for drug users who use it as an open-air shooting gallery and people seeking to escape from law enforcement. The custodian at the junior high school across the street from The Hole said that the site had been there as long as he had been working at the school – 25 years – and police from the local precinct said that they could not remember when this hot spot was not a place where they could go in search of an arrest to pad their numbers.

Staff members at the local harm reduction programs had long known about this, but aside from periodically supplying people at The Hole with harm reduction materials, none of the programs had targeted The Hole with a sustained effort over time, relying instead on people from The Hole visiting them, contrary to the harm reduction ethos of “meeting them where they’re at.” To most of us, though, The Hole was something new, something that we had just heard about that existed once upon a time, something that was emblematic of the “old” South Bronx, but definitely something that had disappeared as crime plummeted across the city and the rate of HIV among drug injectors fell to once unthinkable lows. But it was obvious from our first footsteps into the spiked morass that something was wrong with what we were seeing: how could it be that in a city that had successfully waged war against crime and HIV that a vector for disease, disorder and crime could endure unchecked for decades? The Hole is a persister, but one of a growing number of spaces where the marginalized have found refuge in a rapidly gentrifying New York.

Volunteers filling milk crate tables with supplies in The Hole.

Renting these portapotties and placing them near The Hole was presumptuous: we did not conduct any preliminary work to find out whether injectors wanted them or would use them, and when they did not, it was not a complete surprise. But injectors there said that they understood what our gesture meant, and for that, they were grateful and they were as amused as we were by the prospect of having portapotties available upon demand for injectors, especially ones as nice as these. One of the men that was living at The Hole and who was a leader of sorts said that the portapotties would become popular if they were left there for a period of time, especially in bad weather. We asked if he would be willing to monitor them for us if we rented one for a month and gave him the combination to the lock; he was interested in helping out.

When we left at the end of the day on Sunday, the benches we constructed in The Hole were already being “tagged” – or “claimed” – by users that now had access to a cache of clean injection equipment; we locked up the portapotties for the night and hoped that they would not be vandalized before they were picked up on Monday morning. We didn’t return to the The Hole for a whole week and we didn’t hear from Call-A-Head, so the pick-up must have gone uneventfully, but the following Sunday, we returned to the The Hole to check on the status of our benches and the supplies that we left there. The benches had been heavily used, and there were few supplies left in them, but they needed to be replenished with clean syringes and some of the other essential injection equipment. But more troubling was the mess that it left. For example, rather than use the Sharps containers that had been zip-tied to the benches to dispose of used syringes, people had detached the containers and turned them upside down to use as seats. And given that light at The Hole is never good, especially after dark, it was no surprise that some of the various packages of materials that we left in the benches had been opened, and part of the contents discarded on the ground nearby. Clearly, if this site is going to be supplied with harm reduction materials on a regular basis, there has to be an accompanying effort to keep the place clean. The culture of injection whose norms and conventions currently dominate this place clearly do not put a premium on cleanliness and sanitation – some of the very issues that are hammered upon by harm reduction programs – and all the training and promises that injectors make when they visit the harm reduction programs where many are members go right out the window when they enter The Hole.

REFLECTIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

“Ending the Epidemic” is a popular buzz phrase adopted by the current generation of policy makers, practitioners and scholars who feel that they have a chance to end AIDS (and perhaps related problems) as an outcome of advances in science and their application to the real world. But science and the ‘audit culture’ that accompanies the dissemination of its findings will take us only so far in solving problems like overdose and disease transmission among drug injectors; in fact, a spike in the number of opiate users over the last decade suggests that the problem might get worse before it gets better.

Our portapotty experiment was a statement of need as much as a prescription for action: it’s purpose was to highlight the dire circumstances that injectors face by placing portapotties typically used by upscale customers next to one of the most neglected places in the city and inviting injectors to use them as unsanctioned SIFs, but the fact that they were virtually unused for the two days that they were there underscores the point that solutions to the problems faced by marginalized drug users are not often solved from the top down.

One reason why these individuals might have opted for The Hole instead of our clean, fancy portapotties was the exposure. The Hole is secluded which makes arrests difficult while our portapotties were right in the open on the side of the road. It is important to remember that an arrest does not just mean incarceration, it also means withdrawal. We believe that this weighed into their decisions and further demonstrates the effect that the criminalization of drug use has on users’ culture and how it perpetuates the use of risky injection locations and practices. Providing legal spaces for drug injection, such as SIFs, where people don’t risk arrest may be enough incentive to encourage their use.

Safer injection facilities that are sponsored and regulated by the state have existed for years in other countries and have been proven successful in several respects. Countries such as Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands have been operating SIFs for decades and they have reduced the number of people injecting in public spaces and altered the trajectory for many users whose health and social functioning improved after they engaged with the SIF. Safer injection facilities have been shown to be a useful tool in managing the problems that are associated with injecting drugs, but even a pilot SIF in the US has yet to be launched. And when it is, it promises to be the most audited program of them all.

Another likely reason that the portapotties were not used to inject is that, in principal, they violate the injector community’s ethos around sharing drugs. Drug sharing behavior was obvious to us every time we went into The Hole — small clusters of people huddled around a cooker — and anyone that used the portapotties (which are clearly intended for individuals) would convey a message to others that they did not want to share, disrupting the “moral economy” (Bourgois, 2009). The cessation of drug-sharing behavior has been a major goal of institutional attempts to short-circuit the AIDS epidemic and portapotties are, by design, anti-social. But the fear that heroin users express about suffering withdrawal pains often leads them to develop and maintain large networks of “associates” that will help them when they feel “dope sick” and sitting alone in a portapotty is not likely to help them maintain such a safety net. Sharing drugs, as everyone is well aware, is a risk-behavior for HIV, HCV and many other health problems, but sharing is ingrained in the culture of injectors, and it seems unlikely that portapotties or even a string of state-sponsored SIFs are going to alter that (pending their design). Cultures do change, but if no one is paying attention to those changes — and is focused instead on the minutia of individual attributes — then there is little hope for the development of culturally-informed interventions.

So, our next step is what might be best described as ethnographic immersion in the culture of The Hole: to observe what happens there, to listen to the people who spend time there and to begin to fashion solutions together, especially solutions to group behaviors that place individuals at risk of overdose and disease. But unlike the lone ethnographer who seeks entry to an alien world to write about it, our approach is what might best be described as ‘flash mobbing the alien world’; that is, bringing large numbers of volunteers to The Hole to effect change, partly by virtue of our frequent presence. Our plan is to bring 25–30 young people (college freshmen) at a time to The Hole to spend time there, first to begin cleaning it up — no one will argue that cleaning is not needed — and then, employing ethnographic methods and techniques, like a non-judgmental presence, to alter the social dynamics at the space.

We are entering the truly exploratory stage of our “experiment”, one that will bring together people from different backgrounds, on different life trajectories, to see if they can find some common ground, and if so, if they can work together to fashion solutions to problems that exist in places like The Hole. What makes the experiment doubly interesting — and an investment in the future, perhaps — is that most of the volunteers, the students, are on the path to becoming law enforcement professionals, so they will be interacting with the very people who, in a few years, they will be tasked with arresting, prosecuting, and locking up. Who can predict what will happen as an outcome of this unusual pairing, but history has already shown what will happen if we do not.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank everyone from John Jay, BOOM!Health and St. Ann’s that assisted with this project. In particular, Mohammed Alam, Clarence Colon, June Cortez, Jose Davila, Adrian Feliciano, Nelson Gonzales, Honoria Guarino, Petrit Haxhi, Bart Majoor, Brook Mojica, Kaely Navarrette, Cornelia Preda, Franklin Ramirez, Yeirline Rodriguez, Joyce Rivera, George Santana, Sammy Santiago, Irini Zununi. Partial support for the first author’s time in developing this manuscript was provided by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Service Award (5T32DA007233).

References

- Beletsky L, Davis CS, Anderson E, Burris S. The Law (and Politics) of Safe Injection Facilities in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(2):231–237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.103747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. Righteous Dopefiend. University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis R, Marcus A, Martin Y, West V, Heller D, Cini A, … Drucker E. A report submitted to the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. 2016. Rapid Assessment of “Hot Spots” for homeless people and others in New York City. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kamens DH. PISA, Power, and Policy: the emergence of global educational governance. 2013. Globalization and the emergence of an audit culture: PISA and the search for ‘best practices’ and magic bullets; pp. 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith AR. Opiate Addiction. Oxford, England: Principia Press; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV Risk and Prevalence among New York City Injection Drug Users: 2009 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study. 2010. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Drugs in New York City: Misuse, Morbidity and Mortality Update. 2011 Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/databrief10.pdf.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV Risk and Prevalence among New York City Injection Drug Users: 2012 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study. 2013. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths Involving Opioids in New York City, 2010–2013. Epi Data Tables. 2015:50. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Unintentional Drug Poisoning (Overdose) Deaths Involving Heroin and/or Fentanyl in New York City, 2000–2015. 2016 Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/databrief74.pdf.

- Parkin S. Habitus and drug using environments: Health, place and lived-experience. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shore C. Audit culture and Illiberal governance: Universities and the politics of accountability. Anthropological Theory. 2008;8(3):278–298. doi: 10.1177/1463499608093815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singal J. New York City Should Open Facilities Where Heroin Users Can Shoot Up. New York Magazine. 2016 Sep 29; Retrieved from http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2016/09/new-york-should-open-places-where-heroin-users-can-shoot-up.html.

- Weppner RS. Street ethnography: Selected studies of crime and drug use in natural settings. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson-Stofko B. To save lives, let addicts inject. New York Daily News. 2014 Aug 30; Retrieved from http://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/save-lives-addicts-inject-article-1.1921866.

- Wolfson-Stofko B, Bennett AS, Elliott L, Curtis R. Drug use in business bathrooms: An exploratory study of manager encounters in New York City. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2017;39:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff E. The NYPD Raided A Bronx Homeless Encampment—Now What? Gothamist. 2016 Nov 4; Retrieved from http://gothamist.com/2015/11/04/bronx_homeless_followup.php.